http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk

http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.ukIdentifying the need for palliative care

Challenging behaviours in dementia

Neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia

As we live longer, dementia is replacing cancer as the most feared disease. Dementia affects 5–7% of those over 60 and 20% over 80 years.1 The worldwide population with dementia was estimated in 2014 as 47.5 million.2 At the current rate there will be 850,000 people with dementia in the UK by 2015, and this number is forecast to increase to over 1 million by 2025 and over 2 million by 2051.3 This is contributing to one in four hospital admissions, with the health and social costs of dementia estimated to be more than stroke, heart disease, and cancer combined. Along with these worrying progressive epidemiological figures, we need to take into account the immense caring burden for families, carers, and society.

End-stage dementia often falls between the cracks of specialization, with professionals feeling under-prepared for the intricacies of end-stage dementia management strategies.4 Palliative care has been slow in its involvement for multiple reasons, but primarily because dementia has a much slower disease trajectory than cancer, with an unclear prognosis. In recent years palliative care has become more involved in the complex end-stage dementia patient owing in part to greater publicity of this condition and a political climate to improve dementia care as a result of our ageing population.5

There is a need for improvement in current care to develop compassionate, dignity-enhancing care for end-stage dementia. Palliative care with its holistic management of symptoms, care of the supporting family, and awareness of the process of dying is in an ideal position to provide support for the complex end-stage dementia patient.

End-stage dementia often follows a longer time course, and social problems tend to be the predominant feature for admission in comparison to other palliative care admissions.

References

1. Prince, M., Bryce, R., Albanese, E., Wimo, A., Ribeiro, W., Ferri, C.P. (2013). The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 9(1), 63–75.

2. World Health Organization (2015). Dementia Fact Sheet N0362. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/en/

3. Prince, M.J., Wu, F., Guo, Y., Robledo, L.M.G., O’Donnell, M., Sullivan, R., Yusuf, S. (2015). The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. The Lancet, 385(9967), 549–62.

4. Jackson, T.A., Naqvi, S.H., Sheehan, B. (2013). Screening for dementia in general hospital inpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of available instruments. Age and Ageing, 42(6), 689–95.

5. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2012, updated 2016). Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42

I am a very foolish fond old man,

Fourscore and upward, not an hour more nor less;

And, to deal plainly,

I fear I am not in my perfect mind.

Shakespeare, King Lear, 4.7.69–73

It has always been thought that as we age we lose faculties, and this elderly group have traditionally been labelled as ‘senile’. In the 1960s and 1970s, research showed the degree of cognitive decline was related to pathological lesions in the brain and the decrease in the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh). Alzheimer’s disease was found as the most common cause of dementia, and the term is used by lay people synonymously with the umbrella term ‘dementia’.

Dementia is a progressive broad deterioration of intellectual functionality. Dementia is a clinical diagnosis. This requires memory impairment to be present along with at least one other associated impairment, such as aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or deterioration of executive function (planning, initiating, sequencing, monitoring, abstract thought, and complex behaviour). The condition must be severe enough to interfere with social circumstances, relationships, or work performance, and it must represent a decline from a previous level of performance.1

See Table 20.1.

Table 20.1 Main dementia subtypes

| Alzheimer’s dementia | Insidious onset with changes in memory, personality, communication, and mood. Alzheimer’s is estimated to account for 60% of dementia cases. |

| Vascular dementia | Often stepwise decline in cognitive processing, language, decision-making, and visuospatial ability. Memory loss is often less noticeable than in Alzheimer’s. There are often concurrent vascular problems, especially transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs). |

| Mixed dementia | The majority of dementia patients often have an element of both vascular and Alzheimer components that are difficult to quantify. |

| Lewy body dementia | Complex visual hallucinations are a key feature, as well as sleep disturbances and fluctuations in cognition. There are often symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. It is estimated that 80% of Parkinson’s disease patients develop dementia. |

| Frontotemporal dementia (Pick’s disease) | A rarer form with marked changes in personality and behaviour including disinhibition and impulsiveness. Memory is preserved in the early stages and aphasia is a later feature. This is more common in younger groups (aged 50–60 years). |

| Huntington’s disease | A rarer autosomal dominant disease caused by CAG (cytosine-adenine-guanine) triplet repeat stretch within the Huntington gene. Symptoms include writhing (chorea) movements, progressive dementia, and behavioural problems. |

Differentiating between the different dementia syndromes can be challenging owing to the overlapping clinical features and obscure underlying pathology. Other rarer causes of dementia exist predominantly in younger age groups, such as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and Parkinson’s, plus syndromes such as progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration.

Much individual variability is seen with people with dementia. Median survival with Alzheimer’s disease has been estimated at 7.1 years (6.7–7.5 years), while vascular dementia has been estimated at 3.9 years (3.5–4.2 years). Increasing age and male gender are associated with higher rates of mortality in dementia.2 Co-morbidities which may or may not be related to dementia often exist, making it difficult to determine the contribution of dementia to mortality.

References

1. Pace, V., Treloar, A., Scott, S. (eds.). (2011). Dementia: from advanced disease to bereavement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2. Fitzpatrick, A.L., Kuller, L.H., Lopez, O.L., Kawas, C.H., Jagust, W. (2005). Survival following dementia onset: Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 229, 43–49.

The diagnosis of dementia is difficult. It is estimated that only 50% of patients are formally diagnosed. In England, the National Dementia Strategy from the Department of Health, which was updated in 2015, encourages early diagnosis, as do many independent and governmental bodies.1

The diagnosis is based on cognitive testing, although brain imaging may help. Many tests have been studied, but the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is the best validated, and most studied and commonly used.

Other tests include the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE-R), Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS), the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG), the seven-minute screen (7MS), the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS), and the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI). The MOCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) is a further reliable screening test and is available online for free in 35 different languages.2 The MOCA has also been shown to be somewhat better at detecting mild cognitive impairment than the MMSE.3

Population screening for dementia is unreliable owing to the poor predictive value of the mental assessments, so the current strategy focuses on case-by-case assessment for at-risk groups. Because of the push for early diagnosis and early intervention (Table 20.2), there have been discussions regarding strategies on how to do this.3

Table 20.2 Arguments for and against early diagnosis

References

1. National Dementia Strategy department of Health 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2010-to-2015-government-policy-dementia/2010-to-2015-government-policy-dementia

2. Montreal Cognitive Assessment. http://www.mocatest.org/

3. Robinson, L., Tang, E., Taylor, J.P. (2015). Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ, 350, h3029.

The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a likely consequence of increased awareness and case finding of dementia. MCI is defined as impaired memory for age and education, but with preservation of general cognitive function and functional status. MCI patients are at increased risk of developing dementia; however, MCI fluctuates, with 25–30% of patients improving. There is no evidence that acetylcholinesterase inhibitors reduce progression; they should not be used. This group of patients should be monitored by primary care and re-referral for specialist assessment if symptoms deteriorate. There is an increased cardiovascular risk in this population and this should be addressed. There is some evidence that cognitive stimulation is effective at delaying progression.1, 2

Statins, HRT, vitamin E, and NSAIDs should not be prescribed as primary prevention against dementia.3

The VITACOG study is a small study on patients with cognitive impairment/dementia showing that B-vitamins may reduce progression of cerebral atrophy, and improve memory scores and cognitive function compared to controls (Table 20.3). This is a small study and needs larger confirmatory studies. B-vitamins are readily available over the counter should patients wish to take them.

Table 20.3 VITACOG B vitamin recommendation for ‘MCI’ in the A/W log

| Oral folic acid | 0.8mg OD |

| Oral B12 | 0.5mg OD |

| Oral B6 | 20mg OD |

Reprinted from Jager, C.A. et al. (2012). Cognitive and clinical outcomes of homocysteine-lowering B-vitamin treatment in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(6), 592–600 with permission from Wiley.

References

1. Petersen, R.C. (2011). Supplement to: Mild cognitive impairment. The New England Journal of Medicine, 364(23): 2227–34.

2. Jernerén, F., Elshorbagy, A.K., Oulhaj, A., Smith, S.M., Refsum, H., Smith, A.D. (2015). Brain atrophy in cognitively impaired elderly: the importance of long-chain ω-3 fatty acids and B vitamin status in a randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 102(1): 215–21.

3. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2012, updated 2016). Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42

Dementia is a term incorporating a collection of symptoms with variable aetiology. Any mechanism which causes a progressive cognitive impairment and associated functional loss is a potential cause. This differential is wide, including medication, infections, structural brain lesions, metabolic disorders, toxic chemicals, autoimmune disorders, and para-neoplastic and psychiatric disorders.

Alzheimer’s disease currently has an unknown aetiology with a variety of models proposed. It appears that it is due to a slow inflammatory process altering the brain chemistry and structure, including the development of amyloid plaques and tau protein dysfunction on the background of genetic predisposition.

It is always important to create a differential diagnosis and review regularly as the disease progresses. Some of the secondary/differential causes of dementia are treatable, as are some diseases that imitate dementia, even in the perceived late stages of the disease (see Table 20.4).

Table 20.4 Potentially reversible differential diagnosis

| Depression | Depression should always be considered as it is treatable and the most common disease masquerading as dementia. In comparison with dementia, the onset of depressive symptoms may be more rapid. Depression may be the first symptom of a dementia illness. Older people who were treated for depression showed improvement in cognition without reversibility of dementia, indicating a possible overlap between the two conditions. Depression is more common in vascular dementia. |

| Infection | Delirium is one of the most important reversibilities to recognize early because it is common and treatable. Delirium follows a fluctuating course and can be hypo- or hyper-active. Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) has been proposed to be linked with Alzheimer’s dementia. This is through increased production of amyloid beta and tau proteins in tissue cell cultures, but has not been demonstrated in vivo. There is no current evidence to conclusively link the two diseases. Tertiary syphilis can cause late neurosyphilis, which can manifest as dementia. Treating the underlying infection often produces a partial improvement. HIV dementia is a heterogenous condition requiring HIV antiretroviral treatment. |

| Nutritional disorders | Vitamin B12 deficiency may cause sub-acute combined degeneration, multiple sclerosis–like syndrome, delirium, psychiatric symptoms, and dementia. It was originally thought that B12 supplementation would resolve or improve the dementia. However, there is little evidence to support this, and it is proposed that vitamin B12 deficiency may be an epiphenomenon of dementia rather than a cause of cognitive deterioration. Wernicke’s encephalopathy and Korsakoff’s syndrome are potentially treatable thiamine deficiencies. Wernicke’s encephalopathy is characterized by the triad of ophthalmoparesis, ataxia, and confusion. |

| Alcohol-related | Chronic alcohol abuse is well known to result in deterioration in cognition, behavioural changes, and personality changes. The role of alcohol in the dementia process is still debated, as it is not clear whether there is a direct toxic effect or a secondary cognitive decline due to other factors related to alcohol consumption. Abstinence may improve cognition, but true reversibility is uncertain. |

| Endocrine disorders | Thyroid disturbances can cause depression and memory dysfunction. With the stabilization of thyroid function, memory and mood may return to normal. Idiopathic hypoparathyroidism is a rare disorder that can cause Fahr’s disease (idiopathic basal ganglia calcification). The disease causes dementia, together with other neurological complications (epilepsy, parkinsonism, raised intracranial pressure). Treatment is symptomatic. |

| Metabolic disorders | Multiple electrolyte disturbances, and renal, hepatic, or pulmonary insufficiency, may present as a transient cognitive impairment or delirium that can mimic dementia with or without sepsis. Cognition often is restored after treatment of the underlying disorder. Wilson’s disease is an autosomal recessive disorder causing copper accumulation and toxicity. It presents with psychiatric and movement abnormalities. Treatment is through chelation with penicillamine. Cognitive symptoms are also common and improve with therapy. |

| Poisoning | Lead exposure can cause lead encephalopathy, often presenting in industrial workers. Metals such as mercury, bismuth, arsenic, manganese, and aluminium have also been implicated in dementia. Carbon monoxide intoxication can present with confusion and altered memory. These symptoms may not be reversible even after cessation of the offending agent, though this may prevent further clinical decline. |

| Medications—adverse effects and drug interactions | Psychoactive drugs are the most common cause of drug-induced cognitive impairment (e.g. benzodiazepines, antidepressants, analgesics, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, and anti-parkinsonian drugs). Non-psychoactive drugs are harder to identify as they are often idiosyncratic reactions (e.g. proton pump inhibitors, digoxin, calcium antagonists, corticosteroids, and some antibiotics). Anticholinergic burden: medications with a high anticholinergic burden score can increase the risk of cognitive impairment and delirium in those over 65 years. Examples are tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotics (olanzapine and quetiapine), and antimuscarinic drugs (oxybutynin, tolterodine, darifenacin). |

| Brain lesions | Normal pressure hydrocephalus presents with the classical triad of gait apraxia, dementia, and urinary incontinence. Depending on the time of shunt insertion, urinary incontinence and gait apraxia may resolve and memory may improve. After surgical intervention, patients with haematomas and brain tumours can often see a resolution of their cognitive symptoms. |

| Miscellaneous | Radiation therapy of the brain can cause a dementia. Dialysis has been reported to cause a dementia-like syndrome. These often reverse after cessation of therapy or appropriate treatment, and should be considered in patients undergoing these procedures. |

The degree of reversibility varies depending upon the underlying cause, with some being completely reversible whilst others have only small components of reversibility. For example, treating vascular dementia with anti-platelets may not only improve prognosis but may also allow some recovery in cognition.

With ongoing future advances in treatment of dementias, the distinction between reversible and non-reversible may blur further, and eventually alleviate, arrest, or even reverse the cognitive decline.

There are no interventions that cure or alter the long-term progression of dementia.

There are currently four drugs licensed for treatment with modest overall benefit; a small minority can give a substantial benefit and therefore a trial of treatment is recommended (Table 20.5). NICE guidance recommends that these drugs should be started by a specialist.1

Table 20.5 Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s dementia

| Medication | Side effect | Evidence |

| Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine | Cholinergic stimulation is often dose-related and titration regimes can minimize side effects. Mild Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, anorexia, headaches, insomnia Severe Tremor, agitation, bradycardia, hallucinations, urinary incontinence Caution in patients with urinary retention, asthma, COPD, seizures, and peptic/duodenal ulcer disease. Patients with sick sinus syndrome or supraventricular cardiac conduction disturbances require monthly monitoring at onset, stop if HR<50. Caution in patients with liver impairment as excreted via the liver. | Level 1a evidence from a systemic review of trials. Modest improvement in cognitive function compared to placebo in mild, moderate, and severe disease (NICE). NNT is 12 to achieve a significant benefit in cognitive function over 12 weeks. The NNH is also 12 to cause an adverse effect. |

| NMDA antagonists—moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s dementia | ||

| Memantine | Fewer and less severe side-effect profile than cholinergic drugs. Sedation, dizziness, somnolence, dizziness, constipation, hypertension, and headache. Caution with epilepsy or a history of seizures. Check renal function as excreted via the kidney. | Level 1a evidence There is a small beneficial effect in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease in cognition, mood, behaviours, and activities of daily living. No evidence of benefit in mild dementia but is frequently used off-label. |

Reprinted from Prescribing drugs for Alzheimer’s disease in primary care: managing cognitive symptoms DTB 2014;52:69–72 with permission from the BMJ Publishing Group.

Combination therapy using an AChEI initially with the later addition of memantine can be considered with specialist advice, particularly as the dementia advances. These medications do not currently have licences for other types of dementia; however, in practice, because vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease are often mixed, a trial of treatment is often performed.

There is evidence for benefit in using AChEIs in Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease.

There is evidence that these medications are not beneficial in frontotemporal dementia and MCI.

Dementia medications should only be continued when they are considered to be having a worthwhile positive global effect on cognition, behavioural, and/or functional status. This benefit should be reviewed on a regular basis (initially around 3 months) and the decision should also take into account the holistic picture incorporating the patient’s, carers’, and family’s views. If medication is discontinued, often repeat cognitive assessments 4–6 weeks are performed to assess deterioration, and if significant deterioration occurs during this short period, consideration should be given to restarting therapy.

References

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2012, updated 2016). Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42

Advanced dementia indicates disease progression leading to total dependence upon others. The patient either requires 24-hour care provided by carers at home or admission into an institution (such as a nursing home). The former often has a pronounced burden on the patient’s carers and the latter may lead to institutionalization.

It is the advanced dementia patients who are most likely to benefit from specialist palliative care services. There are often psychobehavioural symptoms in this patient group along with the patient’s loss in their ability to communicate their needs and wishes unambiguously.

Advanced dementia can be defined by multiple scoring systems not limited to, but including, the following:

•<10 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

•Stage 3 (some would include stage 2) on the clinical dementia rating (CDR)

•Stages 6–7 on the FAST score of the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS)

In advanced dementia, not only is cognitive function impaired, but commonly there are many other changes:

•Physical changes—including weight loss, recurrent falls, frailty, epilepsy

•Behavioural changes—frequently agitation, but many other neuropsychiatric symptoms

•Advanced cognitive deterioration—changes in not only memory, but also thinking and reasoning, perception, attention, executive functioning, emotional behaviour, and loss of practical skills

While patients with dementia still have mental capacity, it is important to try to discuss personal wishes for future care, including who should make decisions when the patient is no longer able to do so (advanced care planning). Owing to this being a difficult discussion for all involved, it is frequently put off until it is too late, and there is a lack of guidance as to patient preferences.

Discussions about advance care planning require compassion, sensitivity, and honesty. Those medical professionals who have an established relationship with the patient are best placed to undertake these discussions and commonly find the patient has already thought about such topics. After such conversations, patients can formally record their wishes in several ways.

See Table 20.6.

Table 20.6 Advance care planning discussion outcomes

| Statement of wishes and preferences/advanced statement | This statement is the patient’s wishes for future care and provides a framework by which decisions can be based in the event of capacity being lost. It is not legally binding. |

| An advance directive for refusal of treatment (or ‘living will’) | This statement is the patient’s refusal to receive specific medical treatment in a predefined future situation. It is legally binding and comes into effect when a person loses mental capacity. It has to include the phraseology acknowledging the awareness this decision could result in death. It cannot demand treatments. |

| A proxy decision-maker/lasting power of attorney for health and welfare (England and Wales), welfare power of attorney (Scotland) | This is a legally binding document whereby the patient (‘donor’) nominates another (‘attorney’ or ‘attorneys’) to make decisions on their behalf should they lose capacity. In England, following the Mental Capacity Act, there are two separate aspects to lasting power of attorney, one for an individual’s health and welfare and a second for property and financial affairs. In Scotland, this is similar to ‘welfare power of attorney’ for health decisions and ‘continuing power of attorney’ for financial affairs. Within Northern Ireland it follows common law and can use an ‘enduring power of attorney’ form for financial affairs. |

Identifying the need for specialized input from palliative care clinicians in dementia patients is difficult. Unlike cancer, there are no clear ‘curative’ and ‘palliative’ phases. No treatment cures dementia (with the exception of the rare reversible causes discussed earlier). All treatment is essentially palliative, aimed at symptom control. All dementia management needs to be infused with a palliative ethos.

There are two fundamental questions which need to be answered regarding the referral to palliative care:

Other situations may include providing psychosocial support for the patient or family, respite admissions, rehabilitation, terminal care, and staff support in particularly difficult situations.

There have been a variety of models and criteria suggested to help generalists and other specialists identify who should receive specialist palliative care for dementia.

The SPICT (Supportive & Palliative Care Indicators Tool) recommends a simple question to ask yourself: ‘Would you be surprised if this patient were to die in the next 6–12 months?’.

This question works well at an intuitive level, with a ‘No’ answer being surprisingly accurate at around seven times out of ten for all causes. However, this tool is not a specific tool for dementia, and has yet to be tested exclusively for this population. Dementia patients’ prognosis can be difficult to estimate, but this is nevertheless a very useful tool.

http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk

http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk

The Gold Standards Framework (GSF) is a systematic, evidence-based approach to optimizing care for all patients approaching the end of life, delivered by primary care providers. It is for patients considered to be at any stage in the final years of life. The GSF involves the following:

•identify patients in need of special care

•assess and record their needs

These criteria are not specific for dementia patients; however, there are specific indicators for dementia.

•co-morbidities or other general predictors of end-stage illness

•reducing performance status: the Outcome Assessment and Complexity Collaborative (OACC project)/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)

•dependence in most activities of daily living (ADLs)

•unable to walk without assistance

•urinary and faecal incontinence

•no consistently meaningful verbal communication

•unable to dress without assistance

•reduced ability to perform activities of daily living

•plus any one of the following:

•10% weight loss in previous 6 months without other causes

•severe pressure sores, e.g. stage III/IV

•reduced oral intake/weight loss

Given that there are no nationally agreed criteria for accessing specialist palliative care, the National Council for Palliative Care (NCPC)1 has suggested pointers which should trigger serious consideration:

1.Does the patient have moderately severe or severe dementia?

2.Does the patient also have severe distress (mental or physical) which is not easily amenable to treatment?

•or severe physical frailty which is not amenable to treatment?

•or another condition (e.g. co-morbid cancer) which merits palliative care services in its own right?

If criteria (1) and (2) co-exist, then the patient ought to have full assessment of need and a focused analysis of why they are in distress and how best their symptoms can be improved and distress reduced.

This is not easy, especially for those who rarely witness dying, and even more difficult in the case of the dementia patient who often already has many of the signs of approaching death owing to the pre-existing dementia symptoms. Always take seriously any relatives/carers noting a change in the patient.

•often these are already established in advanced dementia

•increasing weakness and lethargy

•loss of interest in feeding and drinking

•withdrawal from social interaction

•terminal restlessness/agitation

•sometimes newly developed incontinence of faeces and urine

Patients with dementia often have many challenging behaviours and may become agitated for many reasons, including inappropriate responses to distressing situations.

There is overall broad agreement with the current guidelines for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, including those of NICE, the American Psychiatric Association, the BMJ, and the American Geriatrics Society.1,2,3,4 All recommend the use of non-pharmacological behavioural strategies as first-line, but none recommend a particular evidence-based non-pharmacological approach over another. The NICE guideline offers the most comprehensive approach to assessment of underlying causes.

As with all medical quandaries, there needs to be an examination as to the suspected underlying cause. Dementia patients are no different, albeit often requiring a more patient and systematic approach. There needs to be clear consideration given to possible reversible causes.

•Consider using a ‘This is me’ tool, or similar.

•Royal College of Nursing, Alzheimer’s Society (2015)  https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?downloadID=399

https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?downloadID=399

•pain and/or other distressing symptoms

Infections are common in this group and are often the cause of a rapid decline or sudden change, with or without delirium. There should be a low threshold for investigating infection if suspicion is raised. Common infections include UTIs, chest infections, cellulitis, and, often missed, dental infections. The patient’s co-morbidities often provide clues as to the source. Treatment of infection often provides better symptom control than resorting to antipsychotic medication, which has many additional problems. Having a low threshold for investigation into infection (MSU, sputum culture, inflammatory markers) is recommended.

Please see section on pain and other distressing symptoms in dementia, pp. 607–610. A common, often missed cause is constipation.

Please see section on pain and other distressing symptoms in dementia, pp. 607–610. A common, often missed cause is constipation.

The environment in which we reside influences every aspect of our being. The environment should provide a peaceful, relaxing atmosphere with capacity for privacy and socializing. A lack of meaningful stimulation is linked to behavioural issues. People need to engage in constructive activities and social interaction. Within care homes this is increasingly recognized, with regular organized activities often arranged; however, there remains a need to improve the level of stimulation available.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, overstimulation can sometimes cause confusion to the patient. There needs to be a constant routine with expected periods of stimulation built into that routine. This balance is individually assessed and should be based on the patient’s preferences and interests and suited to their capabilities.

References

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2012, updated 2016). Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42

2. American Psychiatric Association (APA) Council on Geriatric Psychiatry (2014, March). Use of antipsychotic medications of to treat behavioral disturbances in persons with dementia [resource document]. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/search-directories-databases/library-and-archive/resource-documents

3. Kales, H.C., Gitlin, L.N., Lyketsos, C.G. (2015). Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ, 350(7), h369.

4. AGS Choosing Wisely Workgroup. (2013). American Geriatrics Society identifies five things that healthcare providers and patients should question. J Am Geriatr Soc, 61(4), 622–31. http://www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/Five_Things_Physicians_and_Patients_Should_Question.pdf

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are non-cognitive symptoms which are generally recognized as being beyond the former ‘in-character’ nature of the patient. If other reversible causes are ruled out, and the symptoms are deemed part of the dementia process, they are commonly known as behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). They often occur in clusters or syndromes identified into groups by the neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI) and are outlined in Table 20.7.

Table 20.7 Neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI)

| Delusions | Psychosis | The NPI was developed as a research tool for application to patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Note: with a predominance of the dementia being characterized by vivid visual hallucinations, delusions, and fluctuating cognition, consider Lewy body or Parkinson’s dementia. This can respond well to AChEIs (e.g. rivastigmine). |

| Hallucinations | ||

| Depression/dysphoria | Mood | |

| Anxiety | ||

| Elation/euphoria | ||

| Apathy/indifference | ||

| Agitation/aggression | Agitation | |

| Disinhibition (socially and sexually inappropriate behaviours) | ||

| Irritability/liability | ||

| Aberrant motor behaviour (repetitive activities without a purpose) | ||

| Sleep disorders (day-night reversal) | Ten behavioural and two neurovegetative areas are included in the NPI. This is further divided into three main syndromes: psychosis, mood, and agitation. | |

| Appetite and eating disorders | ||

Based on modified neuropsychiatric inventory-Q categories. The NPI is scored by the caregiver according to frequency, severity, and caregiver distress at symptoms.

The term ‘BPSD’ arose from the literature; the classification as such does not specify many other specific symptoms. Specific symptoms include the following: easily upset, repeating questions, arguing or complaining, hoarding, pacing, inappropriate screaming (also crying out, disruptive sounds), rejection of care (e.g. bathing, dressing, grooming), worrying, shadowing (following caregiver), sexually inappropriate behaviour, wandering, and rummaging.1

Over 75% of people with dementia develop behavioural problems or psychiatric symptoms at some point during their illness. In those patients able to express themselves, it will be easier to identify whether or not the cause of distress is physical pain or mental incapacity; however, this ability diminishes as the disease progresses. BPSD occurs most commonly in the middle-to-late stages of dementia. Depressive and apathetic symptoms are usually the earliest to appear. Hallucinations, elation/euphoria, and aberrant motor behaviour are usually later. Apathy is the most common persistent symptom (reported in 75% of cases), and delusional symptoms the least persistent.2,3

Low-dose antipsychotics have been historically the choice to manage BPSD; however, antipsychotics (typical and atypical) have been shown to be only of limited benefit in BPSD, with a real risk of increased mortality and unfavourable side effects.

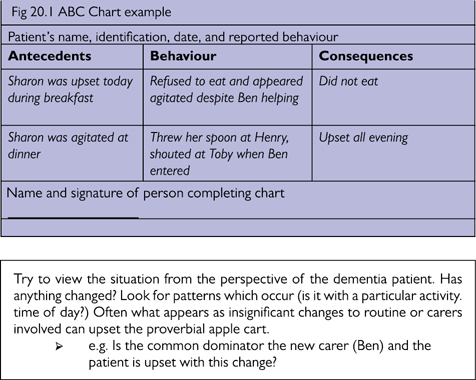

A very simple but useful tool in understanding the origin of BPSD is the ABC chart (antecedents, behaviour, consequences). This should not be used routinely, but for specific behaviours which are proving difficult to understand. See Fig 20.1.

Fig 20.1 ABC Chart example.

Try to view the situation from the perspective of the dementia patient. Has anything changed? Look for patterns which occur (is it with a particular activity/time of day?) Often what appears as insignificant changes to routine or carers involved can upset the proverbial apple cart.

➢e.g. In Fig 20.1, is the common denominator the new carer (Ben), and is the patient upset with this change?

If a patient is at immediate risk of harm to self or to others or in severe distress, medications should be used to manage the behaviour and not the underlying dementia.4

Options here include im lorazepam, haloperidol, or olanzapine. im haloperidol and im lorazepam could be used in combination if rapid sedation is required, but generally a single agent is favoured. im diazepam or im chlorpromazine are not recommended for use in challenging behaviour in dementia patients.

References

1. Kales, H.C., Gitlin, L.N., Lyketsos, C.G. (2015). Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ, 350(7), h369.

2. Management of non-cognitive symptoms associated with dementia. Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin (DTB) 2014;52:114–18. (First published October 8, 2014.)

3. Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (2005, 25 August). Guidance antipsychotic medicines. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/antipsychotic-medicines-licensed-products-uses-and-side-effects/antipsychotic-medicines

4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2012, updated 2016). Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42

It has been shown that non-drug management of behavioural disturbances reduces the need for psychotropic medications.1 These options should be tried first wherever possible. They are often perceived to be time- and labour-consuming, and on occasion are difficult to implement; however, often simple adjustments to social interactions and environment can make a large difference. One should not prescribe antipsychotics without due consideration and preferably a trial of non-pharmacological approaches.

Interventions should be tailored to the person’s preferences, skills, and abilities. For example, a male farmer may respond better to reminiscing and music than a massage, which may be alien to him. Patiently monitor response and adapt the care plan as needed. Depending upon availability, some options are outlined in Table 20.8.

Table 20.8 Potential interventions in behavioural management in dementia

| Active interventions | Environmental interventions |

|

•Familiar surroundings/people/voices •Furniture placement not cluttered; lighting appropriate |

A helpful article is published by the Alzheimer’s Society called ‘Non-pharmacological therapies for the treatment of behavioural symptoms in people with dementia’  https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/

https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/

It is also important to focus on training care staff to understand and manage BPSD. Encourage active engagement from all of the professional teams in the patient’s life story. Often a change in staff culture is needed, with less focus on getting practical jobs performed to an emphasis on individual personal care. Strong positive encouragement is required throughout the multidisciplinary team to pursue this aim.

‘Namaste’ means ‘honouring the spirit within’ and this programme has quantitative and qualitative evidence to support its implementation.2 To qualify for its use, there are entry criteria of one or more of the following:

•sleeps a great deal of the time

•unable to actively participate in activities

Its principles are based on centring on the patient through sensory stimulation (stimulating all five senses) and the patient’s individual story.

•meaningful interaction and activity

•being interested in the patient

•not isolated in bedrooms or inappropriately mixed with those residents who are more able to engage

•no TV (or appropriate music and TV)

•green plants (flowers and seasonal reminders)

•waking up for lunch/tea 20min beforehand

•doll therapy (not child-like)

•therapeutic touch—not using gloves, but ‘like a mother would’, on daily interactions and personal care (often an area of resistance)

Entry into Namaste triggers a family meeting to open conversation about the person’s future planning, establishing goals of care, and beginning the process of getting to know their likes, dislikes, and personality. This requires significant care staff engagement and often further education (designating ‘champions’ of Namaste to maintain and engage the wider team). Feedback from staff, patients, and families has been very positive. Patients had fewer infections and falls and appeared more responsive, communicative, happier, and ‘alive’.

Further psychobehavioural approaches to BPSD can be found in Table 20.9.

Table 20.9 Psychobehavioural approaches to BPSD

| Correcting sensory impairment | Acceptance |

| Non-confrontation | Optimal autonomy |

| Simplification | Structuring |

| Multiple cueing | Repetition |

| Guiding and demonstration | Reinforcement |

| Reducing choices | Optimal stimulation |

| Avoiding new learning | Minimizing anxiety |

| Determining and using overlearned skills | Using redirection |

Data sourced from Zec RF, Burkett NR (2008) Non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment of the cognitive and behavioural symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation 23(5), 425–38 with permission of IOS Press.

1. Fossey, J., Ballard, C., Juszczak, E., James, I., Alder, N., Jacoby, R., Howard, R. (2006) Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: cluster randomised trial. British Medical Journal, 332(7544), 756–61.

2. Stacpoole, M., Hockley, J., Thompsell, A., Simard, J., Volicer, L. (2015) The Namaste Care programme can reduce behavioural symptoms in care home residents with advanced dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(7), 702–9.

3. Zec, R.F., Burkett, N.R. (2008) Non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment of the cognitive and behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer disease. NeuroRehabilitation, 23(5), 425–38.

4. Broady, T., et al. (2018) Caring for a family member or friend with dementia at the end of life: a scoping review and implications for palliative care practice. Palliative Medicine, 32(3), 643–56.

5. Bryant, J., et al. (2019) Effectiveness of interventions to increase participation in advance care planning for people with a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 33(3), 262–73.

6. Watt, A.D., et al. (2018) Ethical issues in the treatment of late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180865.

The use of complementary therapies has increased progressively in recent years. These include aromatherapy, massage, reflexology, reiki, hypnotherapy, acupuncture, and homeopathy.

The amount of quantitative and qualitative research conducted into various complementary therapies is small; however, evidence suggests that patient demand and satisfaction are high. There is some evidence of benefit from the use of aromatherapy and massage in dementia1,2,3 and also dance therapy.4

There is often scepticism about such treatments; however, it is important to remember that the key element is physical contact through touch and the physical and psychological benefits that this creates, not only for the patient but often for the carer. At the end stages of the disease, the carer can often feel excluded or helpless and no longer able to participate in the process of caring. Simple hand massages that they can be taught to carry out with the patient provide comfort and awareness for the carer and the patient.

References

1. Kilstoff, K., Chenoweth, L. (1998). New approaches to health and well-being for dementia day-care clients, family carers and day-care staff. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 4(2), 70–83.

2. Holt, F.E., Birks, T.P., Thorgrimsen, L.M., Spector, A.E., Wiles, A., Orrell, M. (2003). Aroma therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 3, doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003150.

3. Snow, L.A., Hovanec, L., Brandt, J. (2004). A controlled trial of aromatherapy for agitation in nursing home patients with dementia. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 10(3), 431–7.

4. Hokkanen, L., Rantala, L., Remes, A.M., Härkönen, B., Viramo, P., Winblad, I. (2008). Dance and movement therapeutic methods in management of dementia: a randomized, controlled study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56(4), 771–2.

There is scanty evidence for the use of medication in BPSD. The management of delirium or psychosis should be distinguished from the long-term treatment of behavioural disturbances in dementia. Reversible causes should always be considered, investigated, and treated appropriately before resorting to pharmacological measures. Medication is advocated only when non-pharmacological methods are insufficient and the safety of the patient or others is at risk. Whichever medication is chosen, it should be guided by the individual patient and their symptoms and co-morbidities, and the physician’s familiarity with the agent.

Donepezil and memantine have been widely used to treat behavioural symptoms, with variable results. They may reduce the development of agitation, but they appear not to significantly affect agitation already present. They are generally very well tolerated and therefore commonly used.1

SSRIs (citalopram, sertraline, trazodone) reduce symptoms of agitation compared to placebo and appear reasonably well tolerated.2

Mirtazapine is considered a second-line agent, but is a good first-line option for anxiety and agitation, and can cause drowsiness, which may be useful.

There is limited evidence for the use of anticonvulsants (gabapentin, lamotrigine, topiramate, carbamazepine), but some patients may benefit.

Advice is to avoid these medications if possible as their use is associated with further cognitive decline, increased risk of falls and fractures, and in some cases, paradoxically, agitation. They are, however, the preferred medication for delirium secondary to alcohol withdrawal, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and Parkinson’s disease. Z-drugs (e.g. zolpidem, zopiclone) and sedating antihistamines have been associated with cognitive decline and should be avoided.

A large RCT for agitation psychosis in patients with dementia found both atypical and typical antipsychotics no better than placebo in all but a few secondary outcomes.3 Taken together with other studies, the efficacy of antipsychotics in dementia is at best modest.4

Antipsychotic drugs increase mortality in patients with dementia. The mechanism is unknown; however, the risk of stroke with olanzapine and risperidone is 2–3 times higher than with placebo.

Antipsychotics are generally not indicated for behavioural disturbances in dementia and should only be used as a last resort. It is advised to use the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible duration. The efficacy and tolerability of haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine are comparable.

All antipsychotics can cause extrapyramidal side effects, such as akathisia, parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia (long-term use). In patients with Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia, these medications are relatively contraindicated. It is important to look for extrapyramidal side effects regularly with these medications.

Risperidone is a potent D2 and 5HT2A antagonist. Low-dose risperidone is licensed for short-term use in the situation of persistent severe symptoms of psychosis, agitation, and aggression in patients with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s who are unresponsive to non-pharmacological approaches and who are at risk of harm to themselves or others (see Table 20.10). Risperidone has the lowest risk of extrapyramidal side effects compared with the other antipsychotics.

Table 20.10 Risperidone in severe Alzheimer’s

| 250 micrograms BD | Increase after every 2–4 days to usual dose 500mcg BD | Maximum dose 1mg BD. It should be withdrawn after 6–12 weeks |

Haloperidol is a typical antipsychotic D2 antagonist. It is widely used in palliative care for delirium and as an anti-emetic (see Table 20.11).

Table 20.11 Haloperidol in palliative care

| Mild-to-moderate patient distress | Start with 500 micrograms stat and q2h p.r.n. | Increase the dose progressively (e.g. 1mg–1.5mg, etc.) |

| Severe distress or immediate danger to self or others | Start with 1.5mg–3mg stat, possibly combined with a benzodiazepine, and q2h p.r.n. | If necessary increase the dose further, e.g. 5mg |

There is a risk of QT interval prolongation and ‘torsade de pointes’ (particularly if given iv). Caution is required in patients with cardiac abnormalities, hypothyroidism, familial long QT syndrome, or electrolyte imbalance, or if given with other drugs also causing prolonged QT. ECG monitoring is recommended, although in practice is often very difficult.

References

1. Sink, K.M., Holden, K.F., Yaffe, K. (2005). Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA, 293(5), 596–608.

2. Seitz, D.P., Adunuri, N., Gill, S.S., Gruneir, A., Herrmann, N., Rochon, P. (2010). Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2.

3. Schneider, L.S. et al. (2006). Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 355(15), 1525–38.

4. Ballard, C., Corbett, A. (2010). Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with dementia. CNS Drugs, 24(9), 729–39.

BPSD can be made worse by drugs with anticholinergic properties. There should be due consideration to stopping these medications. Please note some of these medications are commonly prescribed in this group, including oxybutynin, antihistamines, and tricyclics.

The higher the serum anticholinergic activity (SAA), the greater the anticholinergic effect, and therefore the greater the risk to the patient. See Table 20.12.

Table 20.12 Medications, commonly prescribed to elderly patients, that have the highest estimated serum anticholinergic activity (SAA)

| High SAA (>15 pmol/mL) | Moderate SAA (5–15 pmol/mL) | Mild SAA (0.5–<5pmol/mL) |

| Amitriptyline | Nortriptyline | Citalopram |

| Doxepin | Paroxetine | Escitalopram |

| Clozapine | Sertraline | Fluoxetine |

| Thioridazine | Olanzapine | Mirtazapine |

| Atropine | Clozapine | Quetiapine |

| Tolterodine | Cetirizine | Temazepam |

| Chlorpromazine | Loratadine | Ranitidine |

| Imipramine | Prochlorperazine | Lithium |

| Chlorphenamine | Baclofen | Haloperidol |

| Hydroxyzine | Cimetidine | Paroxetine |

| Dicycloverine | Oxybutynin | Trazodone |

| L-hyoscyamine | Lofepramine |

Data sourced from Gerretsen, P., Pollock, B.G. (2011). Re-discovering adverse anticholinergic effects. J. Clinical Psychiatry, 72(6), 869; and Chew, M.L. et al. (2008). Anticholinergic activity of 107 medications commonly used by older adults. J. Am. Geriatrics Society, 56(7), 1333–41.

See Fig 20.2.

Fig 20.2 Flow chart illustrating process of care in dementia patients.

Physical pain is a common cause of distress. It is difficult to detect and frequently underdiagnosed in the advanced dementia group. The difficulty in communication or the cognitive processing and conceptualizing of the experience of pain often manifests as agitation, but equally can pass unnoticed owing to subtle signs.

One of the most common requests by patients and relatives is to be pain-free. We can normally communicate the experience of pain through verbalizing, facial expression, and behaviour. These all become increasingly difficult to interpret in advanced dementia. Pain assessment tools may be useful, especially earlier in the disease process; however, they commonly lose effectiveness further in the illness, and pain assessment is purely based on behaviour and observations from the carers.

The dementia process alters the patient’s experience of pain and is likely to affect nociception, cognition, and the emotive components of pain. see Table 20.13.

Table 20.13 Dementia and pain

| Effect on nociception | The dementia process damages the nervous system and may have a direct effect on pain pathways. This may decrease, increase, or alter the sensation of pain. |

| Effect on cognition of pain | Dementia damages all aspects of cognition from the memory in relation to the conceptualization of pain. |

| Effect on emotional response to pain | Dementia can damage appropriate emotional responses and can have effects as varied as indifference to disinhibition. |

Despite these difficulties, experienced carers who know the patient well often can understand the patient’s communications usefully.

With the identification of pain, the usual principles of pain management apply, with escalation up the WHO analgesic ladder. As with all pain management, trying to understand the type of pain (neuropathic, nociceptive, visceral, somatic, bone) is helpful in alleviating the pain effectively.

If it is unclear as to the cause of the distress with no obvious source of pain, but if pain is suspected, consider an empirical trial of paracetamol. In an RCT, an empirical stepwise trial of analgesia (paracetamol—opioid—pregabalin) reduced agitation in unselected patients without a specific indicator of pain.1

Common causes of pain in dementia

•arthritis—osteoarthritis and less commonly rheumatoid or seronegative spondyloarthropathies

•pressure sores—always check skin and common sites

•constipation—monitor bowel movements

•The Doloplus-2 pain scale is a behavioural assessment of pain used in the elderly or in those with cognitive impairment. It has three domains: somatic, psychosocial, and psychomotor. A score of 5 or more indicates pain is present. Scores between patients cannot be compared.  http://prc.coh.org/PainNOA/Doloplus%202_Tool.pdf

http://prc.coh.org/PainNOA/Doloplus%202_Tool.pdf

•The Abbey pain scale is a scoring system for measurement of pain in those who cannot verbalize. Domains include vocalization, body language, facial expression, behavioural change, physiological change, and physical change. A score of 3 or more indicates pain.

http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/862/FOI-286f-13.pdf

http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/862/FOI-286f-13.pdf

Pain is subjective; only the person experiencing it knows what the pain is like. The physiological experience of pain is inseparable from the accompanying psychological and emotional experience.

Dementia affects all aspects of this experience and consequently affects its treatment. An interesting study has shown that Alzheimer’s patients with prefrontal impairment lost their placebo response to analgesia.2 Therefore, along with the likely increased psychological burden on dementia patients, there appears to be a corresponding loss of psychological relief with the placebo contribution. What the patient describes as pain can be the manifestation of these psychological factors or a combination of physical and mental anguish. This overlaps heavily with BPSD, but in holistically managing the patient, we are more likely to be successful if we consider this.

There are a large number of symptoms other than pain which can be present in advanced dementia patients. These are addressed individually in the same way as with every other patient, but with the framing of the difficulties in communication and understanding that dementia entails. As with pain scores, all validated methods of measuring the severity of each individual symptom are severely limited, and often judgement as to symptom severity is based upon astute carers’ observations.

There are a few peculiarities which, although not unique to dementia patients, occur more frequently within this group.

Oral problems cause significant distress, and problems in this group of patient frequently go unnoticed. Xerostomia (sensation of dry mouth), painful mouth, oral thrush, and denture problems are common and require active treatment and close monitoring.

Dysphagia (and odynophagia/sticking) are a common symptom with end-stage Alzheimer’s and sometimes earlier in other dementias. Dysphagia can become a problem very gradually and can remain unnoticed for prolonged periods of time. There is a significant risk of aspiration of food contents into the lungs, and aspiration pneumonia is a common terminal event. The speech and language therapist may be able to analyse the cause of the difficulty and provide useful advice. The occupational therapist can help by providing appropriate feeding implements. Drooling may be an early sign.

•If this occurs in Parkinson’s disease dementia patients, it is important to switch their oral levodopa medications to patch form and not discontinue.

Patients with dementia should be helped to eat and drink for as long as they are able to. Enteral feeding and hydration may be considered in certain circumstances (e.g. if dysphagia is transient). However, where inability to eat is a progression of advanced dementia, enteral feeding or hydration is generally not felt appropriate (NICE).

This topic of discussion is often difficult for family and carers when their loved one loses the oral route. Each case is taken individually with a multidisciplinary approach. Seek expert advice, as enteral feeding is often not the most appropriate course of action. There is some evidence of improved nutrition with enteral feeding, but there appears to be little to no survival benefit, and there is a long complication list. There are patients in which it is entirely appropriate, such as when dysphagia occurs early in the disease process. It is often a good opening to explore the family’s and carers’ expectations of the disease process.

Nausea with or without vomiting is a common and distressing symptom. Diagnosis of nausea without vomiting is difficult: food refusal could make you suspect, however, this is not specific. If there is suspicion, a trial of anti-emetic may be appropriate. An alternative is regurgitation, which classically does not respond to anti-emetics and may be related to dysphagia.

Constipation is uncomfortable, common, and often missed. It is often under-reported for many reasons, but largely because of the nature and perceived embarrassment of the condition. Bowel movements should always be monitored with a stool chart. A pleasant, private toilet with no time pressure should be provided, and discussions regarding laxatives or suppositories should be made early. Per rectum (PR) intervention is sometimes beyond the understanding of the dementia patient, and if required has a lower success rate and requires careful consideration. Often fluid intake is poor in this group of patients, and therefore encouraging increased fluid intake and stimulant laxatives is generally preferred.

Faecal incontinence is very common in advanced dementia. This increases the risk of skin sores and infections such as UTIs. Faecal incontinence should be differentiated from overflow diarrhoea due to constipation. Management is nursing care, incontinence pads when appropriate, consideration of bulking agents, and skin barrier creams (e.g. zinc oxide). Occasionally, once these measures have been taken, diarrhoea can be managed with loperamide or somatostatin analogues can be useful, though there is the risk of constipation.

With immobility and inability to communicate, these simple sensations can become distressing. Dehydration is a common finding in dementia patients, indicating improvements could be made in general care. Eating and drinking is a slower process in these patients, and due time and care need to be given. Discussions early regarding enteral feeding/fluids is often required. Often it is not appropriate; however, each case should be taken on an individual basis and with careful consideration of the whole multidisciplinary team.

Pressure and bed sores remain a significant cause of morbidity in dementia patients. They require vigilance and meticulous care with appropriate equipment to prevent and to treat. A multidisciplinary approach with medical and nursing staff and occupational therapists is important. When severe or complex, specialist input is needed.

See also the section on frailty, pp. 614–617.

See also the section on frailty, pp. 614–617.

‘Frailty’ is used commonly to indicate the overall health state of the patient, including the deterioration of the body systems and the gradual loss of in-built reserves. This is accepted as being related to the normal ageing process (British Geriatrics Society, 2014). Irrespective of the age of the dementia patient, there is an accelerated process of increasing frailty and an increase of associated risks such as falls. There should be awareness of and measures put in place to help manage these increasing needs.

References

1. Husebo, B.S., Ballard, C., Sandvik, R., Nilsen, O.B., Aarsland, D. (2011). Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ, 343, d4065.

2. Benedetti, F., Arduino, C., Costa, S., Vighetti, S., Tarenzi, L., Rainero, I., Asteggiano, G. (2006). Loss of expectation-related mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease makes analgesic therapies less effective. Pain, 121(1), 133–44.

When a person can no longer communicate verbally, is reliant on others for all personal care, and is often immobile, it can become difficult to see what quality of life remains. Those who work closely with people in the severe stages of dementia will be able to point to numerous ways in which the person demonstrates individuality and quality of life. In particular, carers will be aware of when the dementia patient is distressed or calm, content or discontent. The carers often become the advocate for the patient and often devote their lives to fine-tuning the care for their loved one.

As the disease progresses, management of the patient becomes more difficult and often requires professional care. It is often assumed that when a patient is admitted into long-term care that this largely resolves the carers of ‘burden’ and stress. This is often not the case, and the carer is left with feelings of guilt at ‘giving up’, as this may have gone against the expressed wishes of the loved one. This is further amplified when the patient inevitably dies. It is important to recognize the massive changes and emotional turmoil that carers go through. This is often under-recognized and the carers can feel that they have been left unsupported.

The best approach to trying to alleviate some of the carers’ stress is to treat the patient with the dignity, respect, and care the carer has often been doing in isolation. Allowing the carer to participate in, and add pointers in, the patient’s care so that a trusting relationship can be built helps. Until the carer has trust in the care being given, they will be unable to properly relax.

It is useful to highlight the many (often local) support networks available for carers. The social worker or GP usually has a list of local contacts. Financial and legal issues may also need to be addressed.

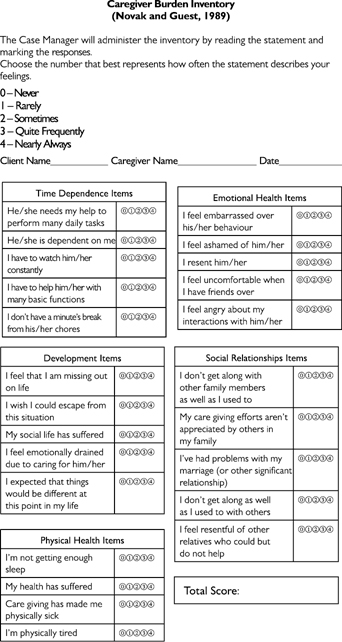

A useful scale for assessing carer burden is the Caregiver Burden Inventory (see Fig 20.3).

Fig 20.3 Caregiver Burden Inventory.

Adapted from Novak and Guest (1989) Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory, The Gerontologist © 1989 The Gerontological Society of America with permission from Oxford University Press.

Owing to their disease, it is impossible to know how aware of impending death the dementia patient is. However, this should not change how you would treat the patient, and good practice is to always assume they can hear and understand you.

There is little specific advice on managing the terminal phase in an advanced dementia patient, but one area worth concentrating on is advanced planning. By anticipating any issues and problems, they can hopefully be avoided. Examples would include enteral feeding or capping recurrent courses of iv antibiotics. These issues could be discussed and agreed in advance of the problems occurring, allowing for a smoother, more controlled progression for all as change occurs.

Along with the medical aspects of future planning, it is worth considering and addressing potential emotional and social issues. There has often been a long course leading up to this point and a lot of conversations have likely occurred. Getting to know the family and exploring the patient’s and family’s wishes and fears about death allows everyone to plan and contribute to the process. Explore any religious, spiritual, and/or cultural needs and rituals. Never assume somebody’s religious or cultural background, as it can cause offence. Always ask.

Frailty is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in older people in the UK. Although it is very common, it has not been given due importance, in part because it is poorly understood and poorly defined.

Frailty is something that most people who live to an advanced age will probably face. Frailty is not really a disease but rather a mixture of the natural ageing process and common medical problems.

Frailty affects how an elderly person will respond to medical treatment, as well as how long and how well they will live.

•If an individual has three or more of the following, they should be considered ‘frail’:

•unintentional weight loss (10 pounds or more in a year)

•general feeling of exhaustion

•weakness (as measured by grip strength)

•low level of physical activity

Source: the Fried Framework, after Dr Linda Fried

Frailty is a reliable predictor of declining health; in particular, the frail are at risk from falls, deteriorating mobility, disability, hospitalization, and death.

By the Fried definition, frailty is not a disease but rather a vulnerable state between being functional and non-functional, and between health and sickness.

Once frailty has developed, it is much harder to reverse than if becoming frail is prevented. To reduce the speed of onset of frailty, it is important to regularly assess for key factors which contribute to becoming frail:

•anorexia, or loss of appetite

•sarcopenia, or loss of body mass

•immobility or decreased physical activity

The elderly may develop loss of appetite as a natural part of the ageing process, but it may also be due to an illness or other factors, and it should never be assumed to be due to ‘just getting old’. The result can be chronic undernutrition and, eventually, fatigue, weakness, cachexia, and micronutrient (vitamins and minerals) deficiencies. Hormone problems such as thyroid or testosterone deficiency can make things worse.

Sarcopenia is defined as an excessive loss of muscle, and may be associated with ageing. While genetically predetermined to some extent, several factors can accelerate the process, including decreased physical activity and hormonal deficiencies.

Immobility can be caused by illnesses such as arthritis, which decreases the ability to move a joint. Joint pain can also lead to frailty through not wanting to be active.

Atherosclerosis contributes to frailty as less oxygen reaches the tissues and organs. Clogging of the arteries can also cause small strokes, which, in turn, can lead to cognitive impairment. In the legs, vascular disease caused by atherosclerosis can result in decreased mobility and sarcopenia.

Balance deteriorates naturally over a person’s lifetime. Decreased balance can initiate a vicious cycle in which accidental falls lead to a fear of falling, which leads to decreased mobility, which makes frailty worse.

Maintaining balance through the use of exercise has been shown to help, and there has been interest in the use of techniques as diverse as tai chi, fencing, and computer sports programmes to help maintain balance in older people.

Depression can result in a reduction in mobility and a feeling of fatigue. Depression also produces a slowing of thought processes. Depressed people are more likely to develop major illnesses, such as myocardial infarction, and to have more difficult, slower recoveries. Depression is also a major cause of anorexia and weight loss in the elderly.

Depression in the elderly is often missed or misdiagnosed as dementia.

Cognitive impairment can lead to a decline in mental processing time and reaction speed, resulting in more frequent falls.

While some aspects of frailty are age-related and irreversible, others are not. Frailty should be seen as treatable and as an important stage on the road to disability and serious illness.

The following list of measures can help reduce frailty, or at least reduce the speed of its onset:

•isolation avoidance (i.e. go out and do things)

•tai chi or other balance exercises

•yearly check for hormone problems

The best treatment for frailty will vary because frailty has different causes in different people.

The first step is to get the best assessment and treatment for any physical or mental diseases that may be contributing to frailty. This may require referral to the Medicine for Older People service at your nearest hospital. After such an assessment, a plan can be devised to meet the particular resident’s needs:

•resistance exercises three times a week, unless major cardiovascular problems

•pain control for pains that inhibit mobility or exercise

•maintain food intake by promoting appetite and serving tasty food in small portions, and consider the advice of a community dietician

•encourage mental stimulation through activities and stimulation

When the frail are dying, they require particular care and attention to protect their skin from developing pressure sores due to loss of subcutaneous fat. This will require regular turning and the use of air mattresses.

With loss of muscle, the frail can develop contractures which are painful, and so keeping joints moving with passive exercises can be very important right up to the last few days. If residents are dying and their joints are stiff, an NSAID such as ibuprofen may be useful in reducing the pain of stiffness.

Relatives often ask about prognosis in such residents, and it is notoriously difficult to predict. The focus has to be on keeping the resident as comfortable as possible on a day-to-day basis.

Frailty should be managed actively.

It should not be assumed that frailty is just ‘normal ageing’.

Deciding where best to manage residents when they develop clinical problems can be difficult and stressful for staff. Sending every resident to hospital is clearly not good care, nor is keeping every resident who develops new problems in the care home.

Some suggestions to help assess where best to manage residents with frailty in UK settings are given in Table 20.14.

Table 20.14 Assessing management location for frailty

| Suitable place of care | Example of resident symptoms |

| Manage in the care home | Frailty has been assessed and reversible causes excluded: in dying phase |

| Manage with help of GP | Unknown cause of frailty, requesting GP assessment: family worried—suffering with frailty but resident has made it clear does not want to go to hospital or too frail to benefit from hospital treatment |

| Manage with transfer to hospital | Rapid development of frailty, having been previously well |

Frailty has always been with us, though today it is increasingly seen not as an inevitable part of ageing but as a condition that in many cases can and should be treated aggressively. Many of the causes of frailty, such as depression, vascular disease, and vitamin deficiency, are treatable and even reversible through a combination of appropriate medical treatment, maintenance of a good diet, and a good exercise regimen.

Further reading

AGS Choosing Wisely Workgroup. (2013). American Geriatrics Society identifies five things that healthcare providers and patients should question. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(4), 622–31.

APA Council on Geriatric Psychiatry. (2014). Use of antipsychotic medications to treat behavioral disturbances in persons with dementia [resource document].

Ballard C, Corbett A. (2010). Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with dementia. CNS Drugs, 24, 729–39.

British Geriatrics Society. (2014). Fit for frailty: consensus best practice guidance for the care of older people living with frailty in community and outpatient settings. British Geriatrics Society in association with Royal College of General Practitioners and Age UK.

de Jager CA, et al. (2012). Cognitive and clinical outcomes of homocysteine-lowering B-vitamin treatment in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(6), 592–600.

Drug and Therapeutic Bulletin (DTB) (2014). Management of non-cognitive symptoms associated with dementia. 52, 114–18.

Drug and Therapeutic Bulletin (DTB) (2014). Prescribing drugs for Alzheimer’s disease in primary care: managing cognitive symptoms. 52:69–72.

Fitzpatrick AL, et al. (2005). Survival following dementia onset: Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 229(30), 43–9.

Fossey J, et al. (2006). Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: cluster randomised trial. British Medical Journal, 332, 756.

Gerretsen P, Pollock BG (2011). Rediscovering adverse anticholinergic effects. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(6), 869–70.

Husebo BS, et al. (2011). Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioral disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomized clinical trial. British Medical Journal, 343, d4065.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2012). Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Retrieved from http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42

Pace V, et al. (2013). Dementia: from advanced disease to bereavement. Oxford: Oxford Specialist Handbook.

Petersen RC (2011). Mild cognitive impairment. New England Journal of Medicine, 364, 2227–34.

Prince M, et al. (2013). The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 9(1), 63–75.e2.

Prince MK, et al. (2014). Dementia UK: update (2nd edn). London: Alzheimer’s Society.

Robinson L, et al. (2015). Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. British Medical Journal, 350, h3029.

Royal College of Nursing, Alzheimer’s Society. (2015). Alzheimer’s Society website. Retrieved 28 Jan 2016 from https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?downloadID=399

Seitz DP, et al. (2011). Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CD008191.pub2.

Stacpoole M, et al. (2014). The Namaste Care programme can reduce behavioural symptoms in care home residents with advanced dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(7), 702–9.

Stock D, et al. (2019). What is the evidence that people with frailty have needs for palliative care at the end of life? A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Palliative Medicine, p.269216319828650.

Thompsell A, et al. (2014). Namaste Care: the benefits and the challenges. Journal of Dementia Care, 2(2), 28–30.

World Health Organization. (2015). Dementia Fact sheet N0362. World Health Organization.