Sexing Nature

The contested meanings of deficiency and sovereignty embroiled anxious late Qing reformers, many of whom were quick to embrace industrial technocracy at the very moment when it was inextricably entwined with the violence of foreign imperialism.1 In this age of great political upheaval, the demise of eunuchism buckled an evolving gradation of civilizational measure, according to which China came to embody the metaphoric projection of a “castrated civilization” and eunuchs a “third sex.” In the last chapter, I argue that the historical production of knowledge about castration is best understood by reading against the evidential grain. This is to avoid a teleological assumption that China had always remained an unchanging “castrated civilization” and that eunuchs had always possessed a transhistorical “third sex” identity. This flattened perspective, in other words, would fix the two historic metaphors onto a sufficient basis for the universalizing claims predicating the mutually generative histories of modern China and the body corporeal. It forces into the past the discursive contingencies upon which Westernization and modernization came to resemble one another in “most of the world.”2 In this chapter, I refocus the connection between the two metaphors by evaluating their transformations under the impact of Western biomedical knowledge.

By delving into a moment in Chinese history that scholars have variously characterized as “colonial modernity,” I aim to tabulate the grounds of new knowledge on which China evolved from a “castrated civilization” into a modern nation.3 The previous chapter foregrounds the transformation of “China” by making eunuchs’ sexual identity an ancillary, rather than a primary, object of historical inquiry. This and the subsequent two chapters follow their collateral changes in a reverse manner: namely, by centering on conceptual issues surrounding the subject of sex over issues relating to China’s changing political sovereignty. If eunuchs had become, rather than having always already been, a cultural relic in this political unfolding, the grounds of knowledge production must have also shifted accordingly so that new kinds of claims, especially scientific ones, could be made about the human body, China’s “geobody,” and their codeterminacy.4 Central to the evolving epistemological grounds of truth about the body, I suggest, lies the emergence and transformation of the concept of sex.

This chapter explores the incremental inception of this “epistemic nexus”: the culmination of new layers of visual evidence that made it possible for sex to become an object of observation. A nascent visual literacy developed in this period that leveraged the remapping of gender boundaries and the consolidation of sex as a biological and biomedical concept. As discussed in the introduction, between the 1860s and the 1890s the urban center of Chinese culture and society shifted from the heartland to the shore.5 Along coastal China, missionary doctors dedicated themselves to translating Western-style medicine, including asylum practices and modern anatomical knowledge.6 Their work stamped the first sustained effort in redefining Chinese understandings of sexual difference in terms of Western reproductive anatomy. Focusing specifically on the first Western-style anatomy text introduced to China, Benjamin Hobson’s A New Treatise on Anatomy (全體新論, Quanti xinlun; 1851), I begin with the mid-nineteenth century as a crucial turning point for the modern visual representations of sex. By comparing Western-style with Chinese-style anatomical studies, I suggest that the visual realm occupied a central role in the reconceptualization of sex and provided a point of commensurate and universal reference for the modern definition of the body. The ways in which the medical visualization of sex had been reoriented, in other words, grounded the formation of a Chinese body politic on the verge of national modernity.

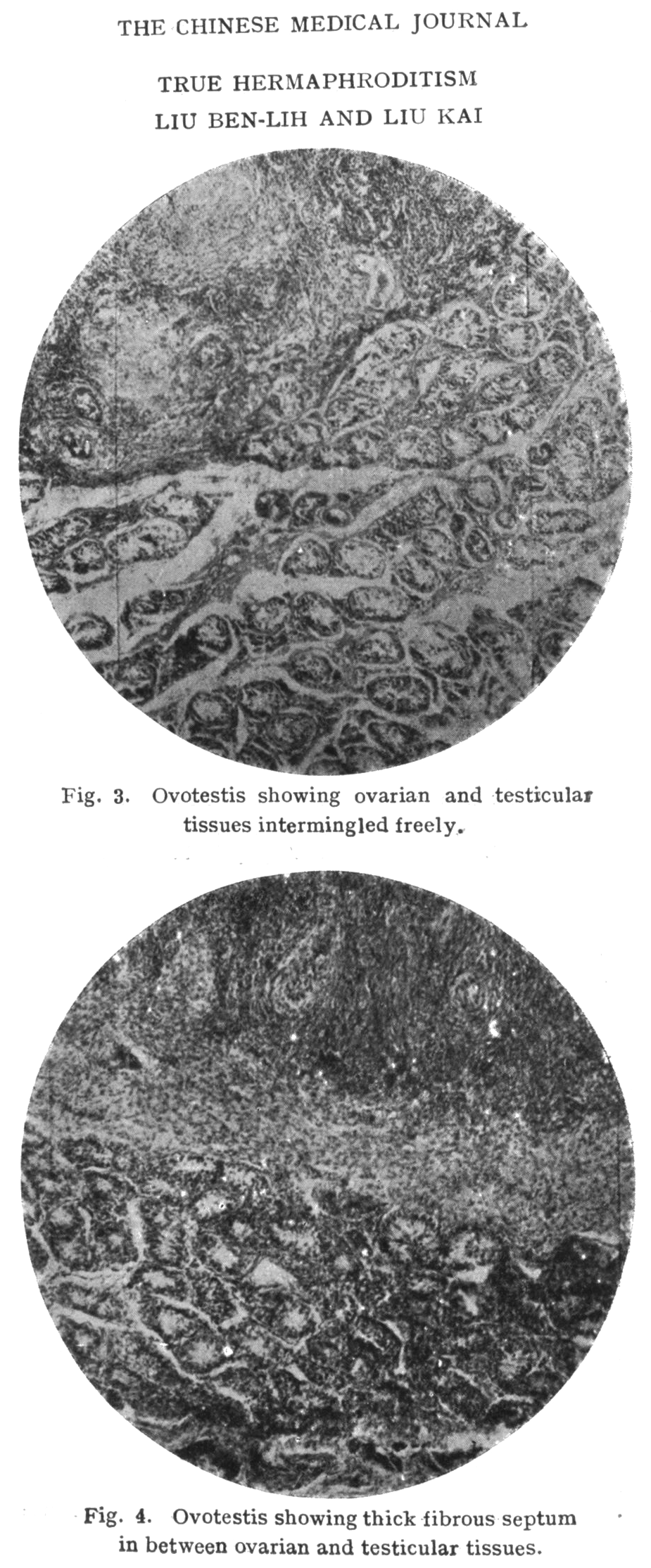

The gradual spread of the Western biomedical epistemology of sex from elite medical circles to vernacular popular culture reached a crescendo in the 1920s. In the years surrounding the New Culture movement (1915–1919), Chinese biologists learned from their Euro-American colleagues to promote a popular understanding of sex dimorphism. Their writings strengthened the visual evidence of anatomical drawings that first appeared in the work of late Qing missionaries. Refining the older drawings with allegedly more “accurate” translations and more diffused apparatuses of observation, they construed the bodily morphology and function of the two sexes as opposite, complementary, and fundamentally different. Republican-era life scientists also provided the first topographic drawings that divided all life forms into ci (雌, female) and xiong (雄, male) types. They bestowed upon the concept of xing (性, sex) an added stratum of visual persuasion by establishing congruity between what they called “primary,” “secondary,” and “tertiary” sexual characteristics. Like Western biologists, they extended these connections to all organisms across the human/nonhuman divide, explaining hermaphroditism with genetic theories of sex determination.

When the “life” of the Chinese nation rose to an unprecedented degree of urgency and uncertainty, scientists offered more intricate ways of depicting sex visually. By the 1940s three techniques of visualization operated conterminously in transforming sex into a scientific concept, the essence of life, and a fundamental object that can be seen and easily identified: what I call the anatomical aesthetic of medical representation, the morphological sensibility of the natural history tradition, and the subcellular gaze of experimental genetics.7 I argue that these three techniques supplied the pivotal pillars for building a new form of visual proficiency that reorganized gender in naturalist terms, establishing the first and foremost conditions under which sex became an object of empirical knowledge.

Anatomical Aesthetic

In the early modern period, medical understandings of the body both shaped and reflected the status, role, and experience of women in society. Conceptualizations of sex in Europe took a decisive turn during the eighteenth century, when the “one-sex” model (which viewed women and men as two versions of a single-sexed body) was eventually taken over by the “two-sex” model (which treated men and women as incommensurable opposites).8 Similarly, the androgynous “Yellow Emperor’s body” gave way to the female gestational body that distinguished itself when fuke developed in Song dynasty China.9 Whether we consider the emergence of the two-sex model in Enlightenment Europe or the rise of gynecology in Song China as a paradigmatic turning point in the history of medicine, the significance of these shifts were not confined to the narrow realm of medical ideas and practices. Rather, these junctures anchored broader conceptual transformations in the relationship between the body proper and the body social.

In fuke medicine, Chinese physicians emphasized the importance of blood in the diagnosis of female-specific ailments. This was best captured by the omnipresent medical cliché, “in women, the blood is the ruling aspect.” According to Charlotte Furth, between the late sixteenth century and the nineteenth century, a “positive model of female generativity” depicted female bodily experience not around symbols of purity and pollution but vitality and loss. Medical texts often associated blood (血, xie) with the female body and described qi (氣) primarily as a male essence. Construed in these dialogical terms with roots in the yin and yang cosmology, women’s medical problems were perceived from late Ming onward as characteristic of bodily depletion and loss. From menstruation and pregnancy to gestation and childbirth, Qing doctors frequently described women as having a physically (and to some degree, emotionally) weak body due to their serious manifestations of blood depletion and stagnation. This shift from pollution to depletion significantly narrowed the scope of gynecological focus on female blood and its reproductive aspect, making it increasingly important to identify the root cause of female blood disorder. Women, unlike men, were often dubbed as the “sickly sex”: Chinese doctors considered female bodies more prone to sickness in general, not only in the reproductive realm but also due other physical processes such as menstruation. Nonetheless, Furth contends that “female gender in the medical imagination implied sources of symbolic power,” since it was represented by a range of images from that “of the ‘prenatal’ cosmic vitality of earth, to the constructive energy of the growing and reproducing body, to the dangerous efficacy of reproductive substances able to cure or kill.”10 By being the “sickly sex,” women served their proper role in the web of Chinese social relations—as powerful agents of reproduction.11

Focusing on childbirth, historian Yi-Li Wu has deepened our understanding of the way late imperial Chinese doctors envisioned the female reproductive body. Although blood was overwhelmingly the central focus of discussion when doctors referred to the female body, Wu shows that “the womb” occupied an equally significant, if slightly different, role in Chinese medicine. “Unlike blood, whose protean nature made it an obvious focus for investigation and therapeutic manipulation, the womb seems to have been largely taken for granted as a relatively stable object whose range of functions and pathological states were more narrowly defined. But fully understanding the intellectual architecture of fuke requires us to acknowledge what Chinese writers took for granted: that blood health and womb health were both essential for successful childbearing.”12

Tracing the earliest medical discussion of the womb to the appearance of the term “bao” (胞) in The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine, Wu notes that doctors also debated on the womb’s actual shape. Beginning in the seventeenth century, some doctors even believed that both men and women had wombs. This de-articulation of symptoms and diseases as being specifically female-linked supported the larger trend in the Qing to retreat to an “androgynous” understanding of the medical body.13 According to Wu, “Even as elite medical doctrine subsumed the female womb into a rhetoric of bodily universality, the treatment of female diseases still assumed that women’s bodies had special morphological features and functions. The dynamic functions of qi and Blood in women, in other words, were inevitably patterned by the physical layout of the female body, and the womb was a key node in the system of hydraulic flows that enabled female fertility.”14 Although Chinese physicians did not share the European obsession with anatomical dissection, late imperial doctors developed a sophisticated lexicon around the condition of the womb to underscore the importance of bodily morphology in their understanding of female reproductive health.

Whether blood or the womb had been the intellectual focus of fuke, Chinese doctors never attributed the cause of sexual difference to an isolated organ and delivered visual representations of distinct male and female bodies on that basis. The introduction of Western, dissection-based anatomies to China, in this regard, denotes an important turning point in the modern Chinese understandings of the body. As many have noted, Benjamin Hobson’s A New Treatise on Anatomy, the earliest of these anatomies, was a landmark contribution to the systematic development of Western anatomical knowledge in the second half of the nineteenth century.15 Hobson was a British surgeon who served as a medical missionary in China under the auspices of the London Missionary Society from 1839 to 1859. Hobson’s text was important because it brought into existence terminologies that crossed Chinese and Western medicine (although many of them were later revised or dropped altogether); it synthesized and distilled a wide range of Western anatomical texts for the Chinese audience (since it was not a translation of one specific text); and it posited an universal corporeal referent (the emerging discourse of race notwithstanding) as the plausible and necessary ground for the cross-cultural translations of bodily meanings.16 In explaining his authorial motives, Hobson commented on the notable absence of refined anatomical knowledge and practice among Chinese doctors: “The human anatomy of internal viscera, bones and muscles, and blood and pulsation is identical in China and the West. Yet, a sophisticated knowledge of it and the mastery of the application of that knowledge are present only in Western countries. There is no comparable phenomenon in China. Is it not a pity?”17

Above all, the transmission of Western-style anatomy to China, as exemplified by the publication of Hobson’s text, produced a radical transformation in “the philosophical priorities and ways of seeing or imagining the body” from the principle of relative function to that of scientific observation so that “concepts of surface, depth, and scale took on a newly finite flavor.”18 This, as Ari Larissa Heinrich has shown, was accomplished through the introduction of a new mode of representation, or what he identifies as the “anatomical aesthetic,” grounded in dissection-based realism.19 Indeed, Hobson’s New Treatise was among the first of a steady stream of illustrated texts in Chinese that in the following decades would find their way into the curricula of medical school classes, the academies affiliated with the arsenals established as part of the Qing Self-Strengthening movement, and even the hands of practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine.20 By the 1910s and 1920s, leading writers like Lu Xun would incorporate the new dissection-based anatomical aesthetic into their own production of literary realism and visions of national modernity.21

In A New Treatise, Hobson used the term “outer kidney” (外腎, waishen) to refer to testicles and “yang essence” (陽精, yangjing) to translate “semen.” He described the anatomy of the outer kidney as follows:

Outer kidney, more popularly known as luanzi [卵子], is the producer of jing [精, “essence”] and the conduit of reproduction; its removal [or “castration,” 閹之割之] will transform the vocal pitch and facial appearance of a man and eliminate his reproductive power entirely.

The scrotum has two layers—inner and outer. There is a middle region, which separates the two luanzi into two halves—or, two sacs. In each sac, there is a [double-sided] membrane region: one side of the membrane connects to the inner layer of the scrotum, and the other side operates as the protective layer of luanzi.

The membrane is often filled with water to maintain moisture. If there is too much water inside the membrane region, the scrotum will appear swollen and luminal. This disorder is called [scrotal] hernia [水疝, shuishan].

The physical appearance of luanzi looks like the flatter version of a bird’s egg. Its length is about an inch, and its width is about eight fen [分, 1 fen = 0.33 cm; roughly 2.64 cm]. A testicle weighs about four to five qian [錢, 1 qian = 3.75 g; so roughly 15g].22

By locating the seat of masculinity in the male gonads this way, Hobson established the conceptual grounds for the physiology of their secretion:

Jing [精, “essence”] is produced from blood, and it appears in the form of a liquid. When one examines it under the microscope, one will discover that it contains many vital entities [活物, huowu] that look like tadpoles. These tadpole-like entities [sperm] have long tails and swim really fast, but their life lasts only a day. These are true for the jing of all kinds of beasts and animals, with the exception that the physical appearance of the vital entities varies.

For teenage boys before the age of twenty, blood does not produce semen. After twenty, blood enters the outer kidney. It moves from testicular arteries [微絲管, weisiguan] into seminiferous tubules [眾精管, zhongjingguan], where the sperm cells are produced. Sperm cells then move from the tubules to [the] epididymis [卵蒂, luandi], and from there to below the bladder through [the] vas deferens [精總管, jingzongguan]; they are stored inside the seminal vesicles [精囊, jingnang, actually at the epididymis].

After elucidating the nature of the male reproductive organ, including its production of the seminal fluid, Hobson unearthed its role in sexual intercourse:

During sexual intercourse, semen is released from the seminal vesicles [through the ejaculatory ducts]. Semen is difficult to harbor, and yet easy to lose [or dispense?]. Adolescents usually lack the maturation of blood and qi and various body parts. So if they allow themselves to indulge in sexual intercourse, the consequences of such behavior range from signs of physical weakness to the possibility of death.

As a practice of remaining lustless, yangsheng [養生, the cultivation of health] comes from reducing the level of desire. If one masturbates to accomplish this, it will be more detrimental to physical health, including the possibility of becoming blind or deaf.23

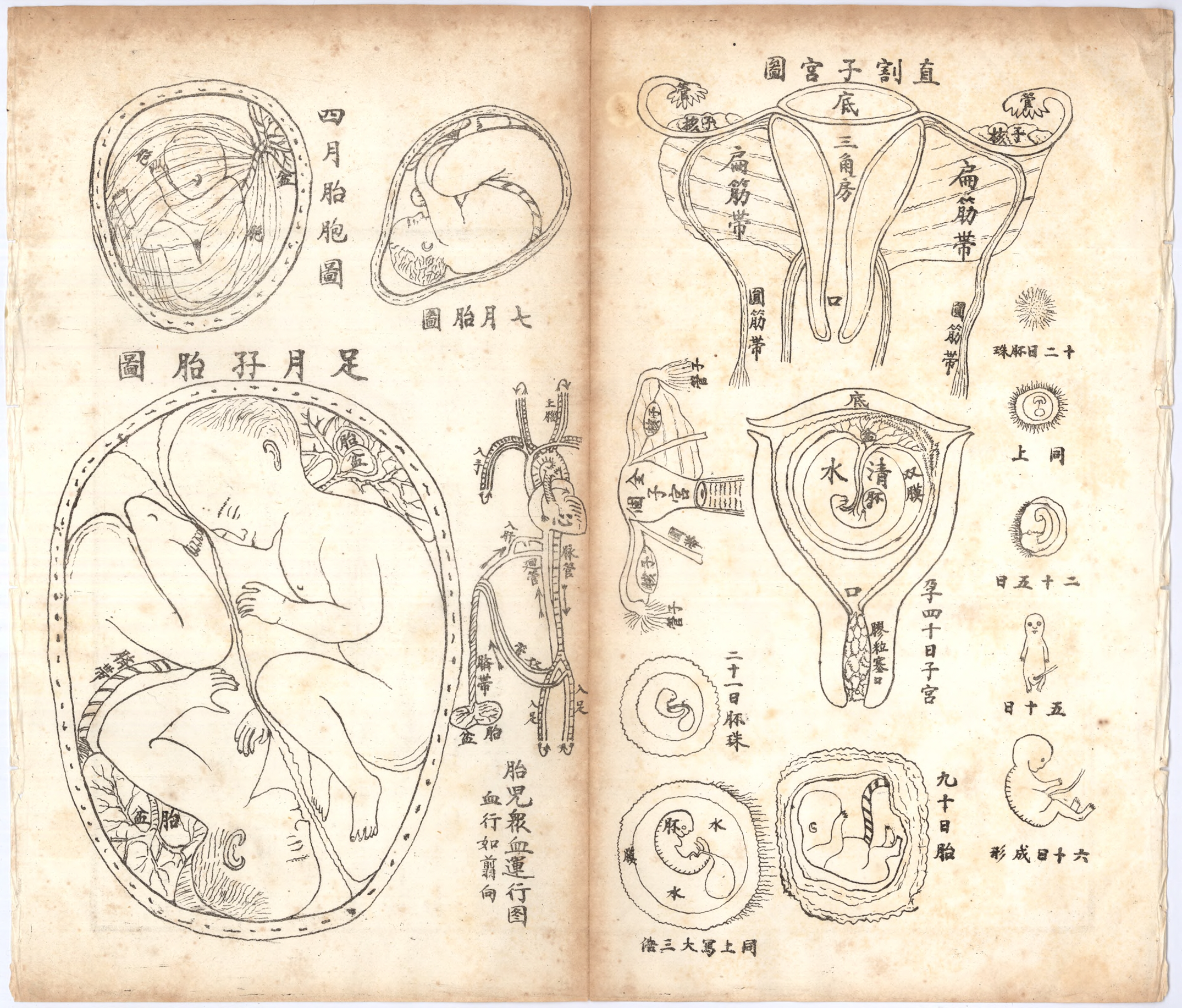

With such a detailed explanation of the male reproductive organ, Hobson provided multiple illustrations of its surrounding area in the body to give the reader both a cross-sectional perspective and a more complete impression (figure 2.1). He also included illustrations of yin (陰), his term for the womb, which contained other crucial parts of the female reproductive organ, such as zigong (子宮, uterus) and yindao (陰道, vagina) (figure 2.2).24 In his Outlines of Western Medicine (西醫略論, Xiyi luelun), Hobson guided the reader with visual demonstrations of the surgical treatment of scrotal hernia (figure 2.3).25 Out of the range of terms that Hobson used to introduce human reproductive anatomy to the Chinese, his words for semen (jing), scrotum (shennang), uterus (zigong), and vagina (yindao), among others, remain today as the standard Chinese translations of the corresponding English terms. Most of these terms were already in use in China, but the main difference between Hobson’s use and earlier Chinese use was that he imposed a one-to-one correspondence between the terms and their anatomical referents. This was accomplished semantically by restricting the meaning of terms that were previously less anatomically specific (e.g., jing) and selecting one term as the only proper term for identifying an anatomical part (e.g., zigong becomes the term for uterus).26

Figure 2.1 Hobson’s illustrations of male reproductive anatomy (1851).

Source: Hobson 1851. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia, Bib ID 1869894.

Figure 2.2 Hobson’s illustrations of female reproductive anatomy (1851).

Source: Hobson 1851. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia, Bib ID 1869894.

Figure 2.3 Hobson’s illustrations of the surgical treatment of scrotal hernia (1857).

Source: Hobson (1857) 1858. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University.

These illustrations were the first of its kind in Chinese to visually depict the male and female reproductive organs in consonance with the anatomical aesthetic of Western medical representation. Unlike the discussions of gender-specific ailments in earlier gynecological texts, these images established for the reader a certain way of knowing about the body in which concrete anatomical terms could be seen in the physical-visual sphere. The profound influence these anatomical images had on their viewers went beyond the mere effects of representation. Even for doctors of professional standing, as medical historian Shigehisa Kuriyama has reminded us, “Dissection is never a straightforward uncovering of truths plain for all to see. It entails a special manner of seeing and requires an educated eye. The dissector must learn to discern order, through repeated practice, guided by teachers and texts. Without training and long experience, Galen insists, one sees nothing at all.… The anatomist aspires to see beyond the immediate, unpleasant material stuff of the body and behold the end (telos) for which each part is fashioned.”27 To grasp the distinctions between Western and Chinese-style anatomical representations, in other words, requires different ways of looking, and this is only possible with the carefully trained “educated eye.”28

Indeed, Hobson’s anatomical images train the eye to perceive the body in a way radically different from before. Whereas Chinese physicians were accustomed to imagining the organs of the body in relative terms within an elaborate system of conceptual correspondence (figures 2.4–2.5), Western anatomy introduced a new concrete sense of depth and closure to the dissected body (figure 2.6). In compiling a compendium like New Treatise, Hobson and other Western missionaries essentially developed a new mode of conceptual and visual engagement, one that relied not only on a critical distance between the viewer and the image of representation but also on an exact sense of the physical locations of what is being represented. Contrary to the anatomical representations found in earlier Chinese medical texts, which assumed no precision in the distance between the viewer and the visual object, Western-style anatomical images turned that distance into the very mechanism of its persuasion.29 Here the introduction of a new mode of representation began to stake an epistemological claim that had been emphatically absent. The anatomical aesthetic of Western medicine, put differently, undermined the link between the represented and the real in Chinese medicine by claiming the physical distance between the viewer and the visual object as the ultimate source of its scientific authority.

To be sure, we are not merely facing a simple difference in the forms and conventions of representation between Western versus non-Western anatomy. It is worth pointing out that, unlike the anatomical illustrations that appeared in Andrea Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (1543) or Bernhard Albinus’ Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis hominis (1747), most of the anatomical drawings in Hobson’s New Treatise embodied a more nuanced kind of natural realism. That is to say, the kind of anatomical illustrations underpinning the works of Vesalius and Albinus were “ideal”—absolute perfect but imagined—composites because some of their artistic fabrications were intended to imitate “the best patterns of nature.” Hobson’s anatomical depictions, in contrast, resembled the drawings found in William Hunter’s Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus (1774): these were “corrected idealizations” that, although aiming to map the internal details of a perfect body, still reflected the effects of nature in slightly more pronounced ways, as demonstrated by the none-too-subtle violence wrought upon the cadaver.30 Decisively absent in these later anatomical illustrations, for instance, include the standing posture of a skeleton or the unfragmented body in whole. These critical eliminations of certain artistic techniques render the body as a direct specimen of the clinical gaze as it is seen rather than with enriched and elaborate imaginations.

Figure 2.4 Diagram of the internal organs in Huangdi Neijing (side view).

Source: Veith 2002, 41.

Figure 2.5 Diagram of the internal organs in Huangdi Neijing (front view).

Source: Veith 2002, 38.

Figure 2.6 Hobson’s diagram of organs visible from anatomical dissection (1851).

Source: Hobson (1851) 1857. Courtesy of the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University.

Moreover, the absence of Western-style anatomy in China before the nineteenth century does not mean Chinese doctors lacked faith in visual knowledge. A handful of surviving records prove that a small number of dissections were performed in the ancient and medieval periods.31 It is also more useful to stress what Chinese physicians actually saw in a body instead of what they did not see: meridian tracts rather than nerves or muscles, the palpation of mo instead of the circulation of blood, and the color of the living rather than the cadaver of the dead. The first of each of these pairs of interest and focus involves a way of conceptualizing the somatic body different from Greek anatomy. Furthermore, the existence of male and female reproductive organs in texts such as Ishimpo (醫心方) since the tenth century and the Manchu Anatomy (康熙硃批臟腑圖, Kangxi zhupi zangfutu) since the eighteenth century, though with limited circulation imposed by the imperial household, implies the possibility that some gynecological experts in imperial China were familiar with these drawings before they read Hobson.32

Nonetheless, the biological basis of visible sexual difference became an object of sustained medical scrutiny only after Western reproductive anatomy had been introduced in late Qing China. It is not that Chinese physicians fell short in differentiating the development of maleness from that of femaleness. In fact, if we turn to the passage in The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine that attempts to achieve the closest to what we are trying to do here, we find evidence for a systematic way of explaining sexual differentiation.

Huang Di asked, “When people grow old then they cannot give birth to children. Is it because they have exhausted their strength in depravity or is it because of natural fate?”

Ch’I Po answered, “When a girl is seven years of age [sui], [her kidney qi (腎氣, shenqi)] become[s] abundant, she begins to change her teeth and her hair grows longer. When she reaches her fourteenth year she begins to menstruate and is able to become pregnant and the movement in the great thoroughfare pulse (太衝脉, taichongmai) is strong. Menstruation comes at regular times, thus the girl is able to give birth to a child.

“When a girl reaches the age of twenty-one years [her kidney qi is stabilized], the last tooth has come out, and she is fully grown. When the woman reaches the age of twenty-eight, her muscles and bones are strong, her hair has reached its full length and her body is flourishing and fertile.

“When the woman reaches the age of thirty five, the pulse indicating [the region of] the ‘Sunlight’ (陽明, yangming) deteriorates, her face begins to wrinkle and her hair begins to fall. When she reaches the age of forty-two, the pulse of the three [regions of] Yang deteriorates in the upper part (of the body), her entire face is wrinkled and her hair begins to turn white.

“When she reaches the age of forty-nine she can no longer become pregnant and the circulation of the great thoroughfare pulse is decreased. Her menstruation is exhausted, and the gates of menstruation are no longer open; her body deteriorates and she is no longer able to bear children.

“When a boy is eight years old [his Kidney qi is replete]; his hair grows longer and he begins to change his teeth. [At sixteen his Kidney qi is] abundant and he begins to secrete semen. He has an abundance of semen which he seeks to dispel; [he can begin unite yin and yang and so beget young].

“At the age of twenty-four [his Kidney qi is stabilized]; his muscles and bones are firm and strong, the last tooth has grown, and he has reached his full height. At thirty-two his muscles and bones are flourishing, his flesh is healthy and he is able-bodied and fertile.

“At the age of forty [his Kidney qi begins to wane]; he begins to lose his hair and his teeth begin to decay. At forty-eight [the yang energy of the head begins to deplete, the face becomes sallow, the hair grays, and the teeth deteriorate.] At fifty-six [his liver qi] deteriorates, his muscles can no longer function properly. [At sixty-four the tian kui dries up and the jing is drained, resulting in kidney exhaustion, fatigue, and weakness.]”33

According to Charlotte Furth’s reading, this passage describes two parallel trajectories for the development of the same, homologous Yellow Emperor’s body. In contrast to Thomas Laqueur’s early European “one-sex model,” what Furth calls the Yellow Emperor’s body is “more truly androgynous” because it “has no morphological sex, but only gender.”34 Furth’s interpretation is compelling especially in the context of her broader argument about the development of fuke. But from reading the above passage alone, one does not need the sophisticated language of gender theory to recognize pregnancy and menstruation as crucial analogs of female bodily process and semen/essence secretion the homologous signifiers of the male body. The mere presence of hair, teeth, bone, and other fleshy body parts does not constitute the concrete ground upon which gender difference can be inferred, although the timing of their development does. In the medicine of systematic correspondence, it seems, the body is truly androgynous insofar as our conception of sex adheres to a modern Western anatomical axiom.

We can at least conclude from the above quotation that the developments of male and female bodies share one thing in common: the kidney being the most important of the five viscera responsible for the regulation of vitality and growth. In fact, this “master system” is the only viscous that is mentioned in the passage in respect of “the generative powers of both sexes.”35 Likewise, the expository text of a Neijing (內經) illustration (figure 2.7) suggests that one of the kidneys is understood to govern the flow of the life forces that contribute to the bodily manifestations of sexual difference. Below is the full passage from The Classic of Difficult Issues (難經, Nanjing) from which part of that expository text has been excerpted: “The thirty-sixth difficult issue: Each of the depots is a single [entity], except for the kidneys which represent a twin [entity]. Why is that so? It is like this. The two kidneys are not both kidneys. The one on the left is the kidney; the one on the right is the gate of life [命門, mingmen]. The gate of life is the place where the spirit-essence [精, jing] lodges; it is the place to which the original influences are tied. Hence, in males it stores the essence; in females it holds the womb [繫胞, xibao]. Hence, one knows that there is only one kidney.”36

According to his commentary, Hua Shou seems to fully endorse the passage: “There are two kidneys. The one on the left is the kidney; the one on the right is the gate of life. In males, the essence is stored here. The essence [transmitted] from the five depots and six palaces is received and stored here. In females, the womb is tied here. It receives the essence [from the males] and transforms it. The womb is the location where the embryo is conceived.”37

Interestingly, this Nanjing passage appeared almost verbatim in Hobson’s A New Treatise under the section “Inner Kidney” (內腎, neishen). Hobson opened the section with this passage to introduce the subtle distinction between the inner, “real” kidney and the outer kidney, a term he reserved for translating “testes.”38 Figure 2.5 presents a Neijing illustration of the relative locations of the five viscera in the body. Right below the center of the diagram, we see a “kidney” (shen) on the left and a “gate of life” (mingmen) on the right. If figure 2.7 leaves room for conflating the two, figure 2.5 allows for no ambiguity. Still, it is difficult to single out any hint of sexual difference (or differentiation for that matter) simply by looking at either of these anatomical illustrations. This is because, insofar as they are intended to support medical claims about gender difference, these Neijing images operated within a structure of knowledge for which the visual depictions of male and female sexual anatomy fell outside its primary “epistemological function.”39 Even in the neo-Confucian elaborations of Zhang Jiebin (張介賓, 1563–1640), a late Ming proponent of the “supplementing through warm” intellectual tradition (溫補派, wenbu pai), the depiction of the “gate of life” derives from the morphology and position of a uterus that is not sex-specific because “men’s essence and women’s Blood are both stored here” (figure 2.7).40

Figure 2.7 Diagram of the kidneys in Huangdi Neijing.

Source: Veith 2002, 26.

In contrast, Hobson’s images posit the relation of truth to sexual nature in terms of physical, visually discernable differences between male and female anatomy. So what his anatomical illustrations enabled was an epistemic shift in the conceptualization of sexual differentiation away from relative theoretical terms and toward concrete visual depiction. Images of Western reproductive anatomy trained Chinese people to connect what could be said about sex to what the eye could see of the physical body, eroding the vested privilege of organ development or functional relativity. With the dissection-based realism, it was now possible to infer anatomical meanings from a static body in its present state rather than having to bring together multiple layers of meaning behind the bodily flow and transformation of vital energy. No longer discussed in such vague, invisible, and even highly esoteric terms, sex emerged as a universal, visible entity from the production of Western medical images. These illustrations reoriented the burden of proof away from the system of theoretical correspondence and into the realm of anatomical appreciation and its attendant techniques of visual comprehension.41 The availability of the more “scientifically objective” images of Western anatomy, which depended on the implicated precision in their distance from the viewer, transmuted into a more “objective” image of Western anatomical science itself. Whereas earlier bodily processes such as menstruation and depletion arbitrated Chinese understandings of sexual difference, the impossibility of mapping such conceptualizations onto the realm of visual depiction is precisely what the new anatomical illustrations sought to overcome. In carrying the weight of science, these images began to define the part of the body that is knowable. As instruments of a new form of visual literacy, they created—and not merely represented—truth.

Morphological Sensibility

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, China’s rapid and unexpected defeat by Japan completely repositioned the two countries’ international standing. The signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895 represented a watershed event in the cultural imagination of China’s power and weakness on both domestic and international fronts. According to Benjamin Elman and Ruth Rogaski, the turn of the twentieth century reversed the positioning of China and Japan in which one “acquired” scientific knowledge and conceptions of health and diseases from the other.42 As the key to maintaining social order, classical learning and natural studies slowly gave way to Western scientific, medical, and technological expertise, which Chinese educated individuals began to master through Japan, as opposed to the longstanding convention in which the Japanese appropriated learned knowledge from the Chinese.43 To be sure, after their interactions with the Jesuits in the “investigation of things and extension of knowledge” during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Chinese literati were exposed to Western science by coming into contact with Protestants in the nineteenth century.44 Yet, to bring Japan into the larger East Asian picture, after waves of Self-Strengthening efforts, many Chinese officials and reformists alike concluded from their global humiliation that Western science and technology held the distinct key to effective modernization. This soon became imbricated with the bourgeoning discourse of nationalism.

The survival of the Chinese nation emerged as one of the foremost preoccupations of government officials, local elites, and educated thinkers after the fall of the Qing. Although immensely shaped by the imported discourse of Social Darwinism and the adjacent discussion of “species,” this preoccupation nonetheless raised a separate but fundamentally related question: the question of life itself.45 At this point, however, the status of popular religion and natural science was so volatile that it is difficult to discern in retrospect whether one or the other was regarded as the ultimate authority for answering questions about life. A top-down state-driven campaign against religious medical practices would come into full force only during the Nanjing decade (1928–1937).46 In the immediate post-Qing period, the relations between science and religion were perhaps not consistently antagonistic, but a variation of this certainly surfaced in the famous 1923 “science versus metaphysics” debate in the New Culture movement.47

The debate reflected a growing tendency among many Chinese intellectuals to approach Western science with a more refined sense of appreciation and commitment. The emerging urban-based, broadly educated class of entrepreneurs and managers, too, grabbed onto the language of “survival of the fittest” and applied the principles of free market competition to international relations.48 It was within this broader political and cultural context that Western biology gained epistemological grounding over classical neo-Confucian cosmology for the empirical understanding of life.49 Chinese thinkers’ gravitation toward the natural sciences led to an exponential growth of translations of foreign biology texts and pictures, which included not only diagrams of human anatomy but also various depictions of the animal kingdom and the natural world. A new technique of visualization emerged from this wave of popular biology books: the morphological sensibility of the natural history tradition. This system of visualization assigned the scientific meanings of sex to all forms of life. By sexualizing the human/nonhuman connection, this normalizing technique expanded and recalibrated the kind of visual objectivity that was still evolving from the anatomical aesthetic of Western medicine.

In the 1920s popular life-science writers first and foremost categorized all higher-level organisms into two distinct types: ci (雌, female) and xiong (雄, male). Chai Fuyuan (柴福沅), author of the popular booklet ABC of Sexology (1928), identified “the two unique organs in higher-level species” as one being “xiongxing [雄性], which produces sperm” and “another cixing [雌性], which produces egg.”50 Similarly, in the succinct words of Feng Fei (馮飛), author of Treatise on Womanhood (1920), “ci organisms are organisms that generate egg; xiong organisms are those that generate sperm.”51 The ci/xiong distinction therefore portrayed higher-level life forms in a dualistic framework. According to Wang Jueming (汪厥明), translator of a Japanese textbook called The Principle of Sex (1926), “There is no xing distinction among lower-level unicellular organisms.… The reproductive cells of the more evolved species are called sperm and ovum, and they mark the difference between ci and xiong vital beings.” Wang continued, “The morphological distinction between ci and xiong is present in all animals, but in varying degrees. We even have terms that reflect this notable difference. For example, the male chicken is called a ‘rooster’ and the female a ‘hen’; the male deer is called a ‘buck’ and the female a ‘doe’; the male cattle is called a ‘bull’ and the female a ‘cow,’ etc.… ‘Sex-dimorphism’ is a term that denotes this difference in biological morphology.”52 To sharpen his point, Wang synthesized the main points of Patrick Geddes and J. Arthur Thompson’s book, The Evolution of Sex (1889), and, based on that information, delineated a list of differences between female (雌體, citi) and male (雄體, xiongti) organisms in binary opposites (table 2.1).53

In ways that had not previously held sway, the human/nonhuman divide came to anchor the entire Chinese biological discourse of ci and xiong. This divide defined what was so decisively different between these two terms and others such as nü (女)/nan (男) or yin (陰)/yang (陽), both of which appeared more regularly in popular discourses. Indeed, the epistemic function of ci and xiong amassed an unprecedented scope of cultural authority in China only after Western biology gained a robust metaphysical foothold. For instance, one finds in Charlotte Furth’s and Judith Zeitlin’s work that the notion of yin and yang prevailed in much of the literary, legal, and medical discussions of hermaphroditism in the late imperial period.54 As ci and xiong became the most widely used pair of biological concepts for conveying sexual difference in the early twentieth century, they gradually replaced yin and yang as the definitive rubric for understanding the relationship between sex and life in the natural world. In fact, the congruency between these two pairs—ci/xiong and yin/yang—precisely relied on their similarity in denoting sex as a form of life.

TABLE 2.1

Sex Differences in Terms of Binary Opposites

雄體 (Male) |

雌體 (Female) |

|

精子生產著 (sperm producer) |

卵子生產者 (egg/ovum producer) |

|

生殖之消費較小 (lower “output” in reproduction) |

生殖之消費較大 (higher “output” in reproduction) |

|

新陳代謝激烈 (higher metabolism) |

新陳代謝不激烈 (lower metabolism) |

|

較為易化的 (affinity for difference) |

比較為同化的 (affinity for similarity) |

|

間有壽命較短者 (lower life expectancy) |

間有壽命較長者 (higher life expectancy) |

|

間有身體小者 (smaller body size) |

間有身體較大者 (larger body size) |

|

色彩多壯麗 (more colorful) |

色彩多質素而不鮮明 (less colorful) |

|

能力之激發者 (more able to stimulate) |

較有耐忍力 (more able to withstand) |

|

性急而為試驗的 (more impatient and experimental) |

較為固執的保守的 (more stubborn and conservative) |

|

變異性較大 (more mutable) |

變異性小 (more stable) |

|

求滿足性慾之意志甚強 (stronger sexual desire) |

務求作家族 (more focused on the family) |

|

較為好鬬 (more ambitious) |

堅固家族 (more domestic) |

Source: Reproduced with my own translation from Wang 1926, 118–19.

Based on the biologizing discourse of sex, writers began to define men (男性, nanxing) and women (女性, nüxing) as human equivalents of ci and xiong. For Feng Fei, “humans represent the most complex biological organisms. Xiong and ci humans are called man (nan) and woman (nü) respectively, and they constitute the most telling example of morphological dimorphism. As such, man and woman are sheer manifestations of the material aspect of the biological world.”55 In an essay written in 1927, “The Evolution of Xing,” Zhou Jianren (周建人, 1888–1984), the youngest brother of Lu Xun, similarly remarked that “in the evolution of sex, after the first step of making a distinction between an egg and a sperm, the second step is thereby to differentiate ci from xiong on the individual organismal [個體, geti] level—the individual organism that produces sperm is identified as xiong and the organism that produces eggs is identified as ci.”56 Connecting ci/xiong to nü/nan and stressing the mutual exclusivity of sex, Zhou defined humans as “animals that are either ci or xiong and not both [雌雄異體的動物, cixiong yiti de dongwu]: those who generate sperms are called nan; those who generate eggs are called nü.”57 According to these formulations, the biological basis of sex dimorphism defined nü as the human counterpart of ci and nan that of xiong. Neither the words “nan” and “nü” nor the concept of shengzhi (生殖, reproduction) were new to Chinese discourses.58 But the novelty of xing in the twentieth century stems from its conceptual operation around which all three terms coalesced to mean sex.

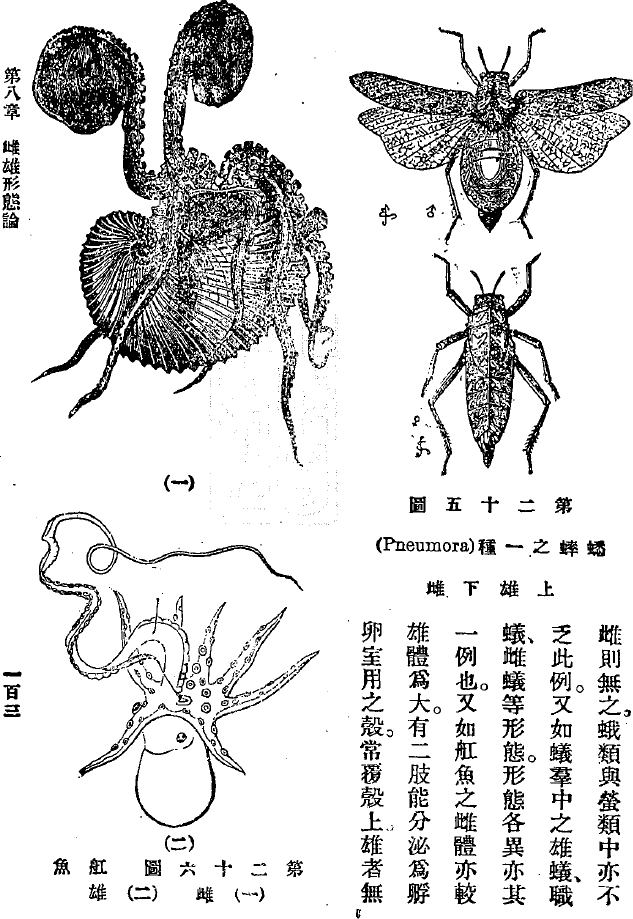

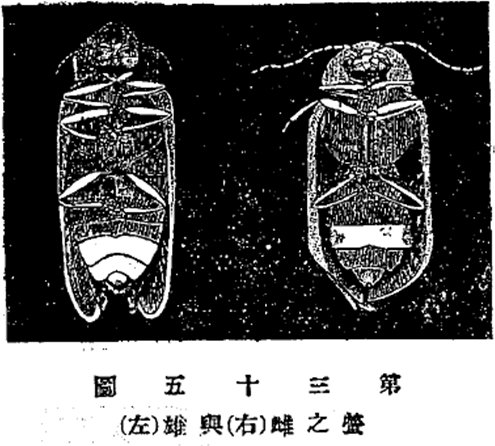

In the 1920s and 1930s, biology books made available visual illustrations of the ci and xiong morphologies of animals and plants (figures 2.8–2.11). These images were not “typical” (Goethe’s archetype), “ideal” (absolute perfect but imagined composite), or “corrected ideal” (Hobson’s anatomical drawings) but were “characteristic” because they located the “typical” in an individual and made the organism depicted to stand for a whole kind of class.59 By pairing the organisms, these drawings situated the qualitative difference between ci and xiong animals on the physical-morphological register. Many of these illustrations may have been direct appropriations from foreign scientific publications. Nevertheless, one notable feature distinguishes them from the pictures produced by the European naturalists in Qing China. Whereas the nineteenth-century naturalists did not systematically label their drawings with ci or xiong, these twentieth-century images invited its viewer to “compare and contrast” the ci and xiong versions of all animal types. This “compare and contrast” effect fundamentally depended on, and in turn crystallized, the new scientific concept of sex.60

Figure 2.8 Ci and xiong morphology of Echuria (spoon worm) and spider (1926).

Source: Wang 1926, 102.

Figure 2.9 Ci and xiong morphology of argonaut and grasshopper (1926).

Source: Wang 1926, 103.

Figure 2.10 Ci and xiong morphology of salamander and yusha fish (1926).

Source: Wang 1926, 110.

Figure 2.11 Ci and xiong morphology of Lampyridae (firefly) (1926).

Source: Wang 1926, 111.

The mapping of a new concept onto the visual representation of nature was an important step in bolstering the objective image of Western bioscience. This connection between the visual and the objective imported new rules for the production of truth about the natural world. Whereas the earlier anatomical drawings allowed people to see sexual difference in the physical human body, the new illustrations reinforced their embedded visual objectivity by broadening the conceptual appositeness of sexual difference. Sex, these new images declared, was an essential aspect of life, so it could be identified not only in humans but across the entire biological kingdom. The visual illustrations did not merely correspond to words or sentences that made up new claims of truth and falsehood, although that, too, was a definitive element of their validity. These pictures “became more than helpful tools; they were the words of nature itself.”61 Viewers of these images learned to accumulate “a form of cultural capital,” to borrow communication scholar Scott Curtis’s remark from a different context, as “scientific observation functions very much like the cultivation of distinctive aesthetic taste.”62

The kind of morphological sensibility groomed in these images persisted well into the period after the War of Resistance (1937–1945). The best example comes from none other than the work of one of the leading authorities in reproductive biology in twentieth-century China, the embryologist Zhu Xi (朱洗, 1899–1962), best known for his study of the parthenogenesis of frogs. Throughout the late 1930s and the 1940s, Zhu authored and revised a total of six monographs in a book series called Modern Biology (現代生物學叢書, Xiandai shengwuxue congshu; published by Wenhua Shenhuo Chuban She [Cultural Life Publishing House]). The series introduced various subjects in Western biology to the Chinese lay public.63

According to historian Laurence Schneider, the history of Chinese genetics and evolutionary biology can be seen as an example of “how modern science was transferred to China, how it was established there and diffused throughout culture and institutions.”64 Indeed, numerous Republican-era Chinese magazine articles, periodicals, books, and pamphlets published under the banner of “biology” were not always written by individuals belonging to formal establishments of natural scientific research, such as at Peking, Qinghua, Yanjing, or Nanjing Universities. Zhou Jianren, for instance, was one of the most reputable popular life-science journalists at the time. Unlike his two elder brothers, Zhou remained loyal to his interest in science (rather than literature for example) and earned his bachelor’s degree from the Agricultural School of Tokyo Imperial University. He frequently published articles and opinion pieces in popular periodicals such as the Eastern Miscellany (東方雜誌, Dongfang zazhi) and the Ladies Journal (婦女雜誌, Funü zazhi). His writings that defended Lamarckism during the Republican period and Lysenkoism after the rise of the Chinese Communist Party attracted a much wider readership than the technical writings of professional geneticists.65 In tackling the riddle of life, Zhou belonged to a global community of science translators who challenged the “universal language” of science outside the modern West.66

In this respect, Zhu Xi and other notable Chinese geneticists such as Tan Jiazhen (談傢楨, 1909–2008) and Chen Zhen (陳楨, 1894–1957), a student of E. B. Wilson, represented a group of more formally trained but esoteric biological scientists.67 Born in Linhai, Zhejiang Province, Zhu went to France with several friends in May 1920 as participants in the anarchist Li Shizeng’s (李石曾, 1881–1973) “work-study programme.” According to his autobiographical account, they received no assistance from the Sino-French Education Association upon arriving in France, so they had to live in tents on the lawn in front of the Chinese Federation. Eventually, they were allowed to sleep on the floor of the building on a temporary basis. During the first five to six years of his life in France, Zhu’s experience was quite typical of Chinese young adults who decided to join the work-study program and travel overseas: frequent job changes, difficult physical labor, poor living conditions, unending negative encounters with Westerners, and an increasingly entrenched sense of disappointment and despair. Nevertheless, Zhu eventually attended the University of Montpellier and studied embryology under J. E. Bataillon from 1925 to 1932. After earning his doctorate in biology from Montpellier, Zhu returned to China and began his academic career as a professional biologist. From 1932 on, he was associated with the National Zhongshan University, the Beijing Academy of Sciences, and various private research organizations. Zhu became a member of the Experimental Biology Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1950 and was appointed as its director three years later.68

Before joining the institute, Zhu authored and expanded his six monographs for the Modern Biology book series, the aim of which was to introduce a wide spectrum of Western biological ideas to the Chinese nonexpert public. In his general preface to this six-volume project, Zhu declared:

My intention in publishing this series of monographs is to offer my knowledge in biology to the lay reader in a systematic way, hoping that it will encourage a better understanding of human life. The topics of our investigation include the origins of human beings, the evolution of their ancestors, and the development of human thinking, behavior, and moral consciousness. Simply put, we need to analyze ourselves, study ourselves, and understand ourselves; after cultivating this sort of understanding we need to improve ourselves, allowing humans to be part of science and to march forward in a more reliable destiny.69

This statement shows the conviction Zhu shared with many other modernizing thinkers (not only scientists) in the Republican period that it was important to acquire a general knowledge about life through a scientific way of thinking rooted in Western biological, especially evolutionary, ideas.70 He therefore opened his series with a volume called Humans from Eggs and Eggs from Humans (蛋生人與人生蛋, Danshengren yu renshengdan), which described various aspects of the developmental phases of life, including detailed accounts of male and female reproductive anatomy (as well as an interesting chapter on teratology).71 In this first volume, Zhu distinguished humans from animals, plants, and other living species in ways that would become even more vivid throughout his subsequent writings—by holding up sex as an integral dimension of life.

In Changes in Biological Femaleness and Maleness (雌雄之變, Cixiong zhibian; 1945), the fourth volume of the series, Zhu began his scientific investigation of sex with an opening chapter called “The Conceptualization of Ci and Xiong” (雌雄的概觀, Cixiong de gaiguan).72 He argued that the distinctions between ci and xiong (or nü and nan when he referred to humans) bespoke the most important calibers of differentiation in living species—animals, plants, and humans.73 Similar to the visual illustrations of ci and xiong species circulating in other popular biology books, his hand-drawn images of different organisms served one simple purpose: to enable the viewer to grasp from a critical distance the nature of sexual difference across a spectrum of life forms (figure 2.12). Above all, these images must be understood as the product of visualization rather than mere representation.74 They teach the eye to recognize specific patterns and assist the reader to discriminate ci from xiong through the knowledge of seeing. Whereas pictures 6, 8, 11, 13, and 15 all refer to the xiong versions of a particular species, pictures 7, 9, 12, 14, and 16 indicate their ci counterparts. The very marking of such characters as “ci” and “xiong” on the diagrams indexes these words’ epistemo-logicality, according to which their semantic logic, usage, coherence, and possibility became visually equated with the dualistic physical structures of life.

Figure 2.12 “The Morphological Differences Between Ci and Xiong Animals” (1945).

Source: Zhu (1945) 1948, 33.

Similarly, although the visual illustrations in other biology books (figures 2.8–2.11) were presented as if they truthfully described reality, they were in fact establishing new boundaries within which claims of truth and falsehood about sex could be made. As ethnomethodologist Michael Lynch has noted, visual representation in science is really about “the production of scientific reality.”75 Since these images did not simply represent nature, they had deep implications for the negotiation of truth claims. In the case of xing, they claimed an autonomy of sorts by showing that morphology nested the seat and nature of sex. Figures 2.8–2.12 were not just passive aids for learning, but they prescribed for the reader the conceptual boundaries of life and the forms in which it took shape, such as through the binary manifestations of ci and xiong. In other words, the “scientific” reality of sex, or sexual difference, depended on the way the morphological sensibility of these images reinforced the anatomical aesthetic of the earlier medical representations. Although the word “xing” did not yet mean “sex” before the twentieth century, the visual mappings of biological form made it possible for the earlier anatomical drawings and the later naturalist illustrations to be merged into the concept of sex by the 1920s. By claiming a scientific status for the images they produced, both techniques of visualization ultimately secured an objective image for the sciences themselves.76

In the new discursive context of the ci/xiong distinction, natural science writers incorporated the anatomical aesthetic of medical representation. They often included in their books detailed descriptions and drawings of human reproductive anatomy. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, examples could be found in Chai Fuyuan’s Sexology ABC, Zhu Jianxia’s (朱劍霞) edited translation of The Physiology and Psychology of Sex (1928), Li Baoliang’s (李寶梁) Sexual Knowledge (1937), and Chen Yucang’s (陳雨蒼) Research on the Human Body (1937), among other professional and periodical publications (figures 2.13–2.16). The circulation of these images continued a long tradition of the cross-cultural translation and dissemination of Western anatomical knowledge, an endeavor dating back to as early as the seventeenth century. As discussed in the last section, in the nineteenth century, medical missionaries including Benjamin Hobson (1816–1873), John G. Kerr (1824–1891), John Dudgeon (1837–1901), and John Fryer (1839–1928) extended and revised this intellectual trajectory.77 Interest in anatomical knowledge came of age in the early Republican period in part as a result of the passing of the Anatomy Law in November 1913, and by 1920 regular, though limited, dissections were performed in treaty-port medical schools.78

Figures 2.13a and 2.13b Zhu’s anatomical diagrams of male and female reproductive organs (1928).

Source: Zhu 1928, 42, 48.

Figure 2.14 Li’s anatomical diagrams of the female reproductive system (1937).

Source: Li Baoliang 1937, 33.

Figures 2.15a and 2.15b Chen’s anatomical diagrams of male and female reproductive organs (1937).

Source: Chen 1937, 166, 171.

Figures 2.16a and 2.16b Chai’s anatomical diagrams of male and female reproductive organs (1928).

Source: Chai (1928) 1932, 19, 37.

The new illustrations of the Republican period not only updated many of the previous “errors” and “mistranslations” but also consolidated a systematic language of maleness and femaleness in the universal terms of bioscience. For example, one finds great resemblance between the diagram of the female reproductive system on the lower right hand side of figure 2.14 and the one next to the center of figure 2.2 from Hobson’s treatise.79 Whereas late Qing missionary anatomical drawings were circulated mainly among the medical elites, especially those who were less resistant to Western biomedicine, Republican-era anatomical illustrations were printed in popular publications, found a ready audience, and thereby reached a critical mass.80 Above all, the popularization of the anatomical aesthetic demonstrates that “what is accepted as true knowledge ultimately depends not exclusively on truth claims negotiated among experts but required public mediation.”81 The sheer quantity and accessibility of this new cohort of illustrations not only reinforced the visual authority of late Qing anatomical drawings, but they also demonstrate that, at least by the 1920s, the epistemic jurisdiction of the Western biosciences was advocated even by native writers.

From Gender to Sex

In the novel language of bioscience, physical structure and morphology reflected, rather than predetermined, human gender difference. More often, popular writers claimed that the secret of masculinity and femininity resided in the gametes and gonads, which formed a crucial part of what biologists called “primary sexual characteristics.”82 In this spirit, Gao Xian (高銛), the translator of another Japanese biology textbook, Sex and Reproduction (1935), posited a broader definition of ci and xiong that incorporated the role of anatomical parts: “Organisms in the animal kingdom that either generate spermatozoa or have a testis that produces it are called xiong (male); those that generate ovum or have a functional ovarium that can produce it are called ci (female).”83 For Gao, the essence of ci-ness and xiong-ness entirely depended on the “actual presence of a testis or an ovary,” which constituted “zhuyao tezheng [主要特徵] (principal sexual character),” and those bodily features that “bear some immediate relevance to the principal sexual character are called fudai tezheng [附帶特徵] (accessory sexual character). Together, they are called diyici xingtezhen [第一次性特徵] (primary sexual character).”84 The anatomical drawings (figures 2.13–2.16) therefore provided unequivocal visual evidence for the natural existence of primary sexual characteristics. These images educated the eye to see what normally could not be captured beyond the exterior features of the human body. In other words, the anatomical aesthetic of these medical representations allowed the viewer’s gaze to penetrate the external integument of the body, a fundamental attribute of the morphological sensibility of the natural history tradition. Here we begin to see how the two techniques of visualization worked in a mutually productive fashion.

If the seat of masculinity and femininity could be inspected in these anatomical drawings, morphological appreciation was still important for distinguishing these features from what biologists called “secondary sexual characteristics.” Chinese scientists often credited the British surgeon and anatomist John Hunter (1728–1793) as the originator of this idea. According to Gao’s definition, “coined by John Hunter, dierci xingtezhen [第二次性特徵] (secondary sexual character) typically refers to variations in body size, morphology, color of physical appearance, sound production, odor and its intensity, illumination and its intensity, parts of the body that illuminate, etc. among normal animals.”85 Wang Jueming, in translating The Principle of Sex, summed up the definition of “secondary sexual characters” rather cogently: “a concept invented by Hunter and adopted by Darwin” that referred to “sexual characters that bear no direct relationship to biological reproduction.”86 Labeled “secondary,” physical features such as the antlers of the male deer helped to build a perception of the difference between ci and xiong animals as an immutable distinction of nature (illustrations 8 and 9 in figure 2.12). The morphological sensibility found in figures 2.8–2.12 precipitated a form of visual assertion precisely by contrasting the physical appearance of male and female species. Like the anatomical aesthetic of medical representation, it put the viewer in a position where it was still possible to determine the sex of the object represented on the page; the crucial difference, though, was that this process of “sex determination” was made possible not by looking beneath the layers of the skin but by looking precisely at those physical features that are externally visible.

Compressed into the congruence between ci/xiong and nü/nan, the visuality of sex extended “secondary sexual characteristics” to human forms. In Sexual Knowledge (1937), Li Baoliang asserted that “the best examples of secondary sexual characteristics in humans include women’s smaller physique, paler pigmentation, softer skin, richer body fat, and less well-defined muscles in comparison to men.” Other features of human “secondary sexual characteristics,” according to Li, included men’s hairier bodies, lower-pitched voice, and narrower pelvis (figure 2.17).87 Li reasoned that women had wider pelvises due to their procreative functions, not unlike how their biological capability to breastfeed led them to easily develop larger breasts. “Therefore,” wrote Li, “many scientists have observed wider female pelvises among people of races on the higher end of the evolutionary scale. This is because the brain size of the babies of better races tends to be larger, and larger pelvises would allow a better fetus to develop inside a woman’s womb.”88 The extension of secondary sexual features to the human body developed a visual framing of sex dimorphism in all living beings as a fundamental product of nature.

Ultimately, though, it was the naturalization of the very connection between primary and secondary sexual characteristics that cemented the visual culprit of xing. By naming all those sex features not directly involved in reproduction “secondary,” observers described human gender difference as the natural outgrowth of “primary” characteristics, characteristics that also determined sexual difference in animals. This biologizing discourse posited the fundamentals of maleness and femaleness beneath the surface of observable bodily features. It was with this in mind that Shen Chichun (沈霽春), author of The Life of Sex (1935), argued that although “women have large breasts; men have beards,” these “do not constitute quintessential gender difference [根本上的夫婦之別, genbenshang de fufu zhibie],” because “quintessential gender difference refers to anatomical difference [解剖上的區別, jieposhang de qubie].” Shen explained that “if an ovum [卵粒, luanli], a yolk [卵黃, luanhuang], and an oviduct [輸卵管, shuluangguan] are found inside an animal after dissection, then the organism is ci. If testes and vas deferens are found, the animal who has sacrificed his life [for the dissection] should be xiong.”89 As Yi-Li Wu has pointed out, late imperial Chinese physicians regularly considered breasts and beards as the primordial physical markers of gender difference.90 Shen’s assertion was thus first and foremost a riposte to this longstanding Chinese belief. In his implicit gluing of human gender difference to the ci/xiong distinction, Shen instructed his reader to consider a layer of truth, in relation to nature, beneath the visible horizon. These anatomical and morphological drawings enabled Chinese readers to comprehend sex beyond the physical markers of breast and beard and to locate the biological roots of manhood and womanhood in gonadal biology.

Figure 2.17 “The Pelvises” of men and women (1937).

Source: Li Baoliang 1937, 41.

Apart from primary and secondary sexual characteristics, cultural commentators often spoke of “tertiary” ones, too. They univocally attributed this concept to the British sexologist Havelock Ellis (1859–1939).91 Pursuant to Wang Jueming’s translation of The Principle of Sex, the notion of “tertiary sexual characters” was “invented by Ellis to highlight unique features of male and female bodies. Tertiary sexual characters are not as obvious as secondary ones, but examples abound.”92 The differences in skull size, body height, level of physical activity, blood cell count, and cerebral regions in the brain between men and women were some of the examples he enumerated. Sexual difference in these somatic traits, according to Wang, may come across as less significant to a zoologist than, say, a sociologist or an anthropologist. As such, “even if they cannot all be grouped under secondary sexual characters, it is still useful to include them under the broad category of tertiary sexual characters. Although this concept has been endorsed variously by Papillault, Haeckel, P. Weber, and Kurella, each scientist outlines a different set of criteria for associating it with certain sex-specific features.”93 Tertiary sexual characteristics thus welded an important scientific vocabulary (and the cognate set of visual proof) to naturalize those sexual/gender differences that bear no immediately obvious relationship to chromosomal or gonadal sex.

Simply put, what the cultural discourse of bioscience mediated in the early Republican period was the transformation of previous bodily “gender” into the modern notion of “sex.” Some historians have used the blanket term “scientism” to explain the optimism that many Chinese intellectuals expressed toward Western scientific principles and practices in the early twentieth century, but they rarely, if ever, specify the underlying mechanisms of knowledge production by which the cultural authority of that optimism came about.94 More recently, historian Sean Hsiang-lin Lei has provided an illuminating account of how Chinese medicine became increasingly legitimated through the application of modern scientific methods—a process he termed “scientization” (科學化, kexuehua)—in the 1930s and 1940s. The effort of the Nationalist state in forcing practitioners of Chinese medicine to cope collectively with the concept of science for the first time resulted in several innovations, most notable of which involved the incorporation of the germ theories of disease into Chinese medicine and the laboratory and clinical research on traditional drugs.95 Gaining credence in the same historical context, what I have been calling “techniques of visualization” shift to the visual authority of scientific claims. Cumulatively, these techniques explain the epistemological procedures that facilitated the envisioning of scientific optimism—primarily through the power of image. As we have seen, in their effort to challenge neo-Confucian prescriptive claims about gender hierarchy, urban elites drew on natural scientific knowledge to recast gender distinction in terms of biologically determined structures. More specifically, they relied on the anatomical aesthetic of medical representation and the morphology sensibility of natural history to establish an intrinsic nature of sex that could be identified visually and universally.

Relying on the concrete physical structures of sex, these scientific elites also reconceptualized functional processes of the body. Earlier cultural vestiges of femaleness, such as menstruation, were now reframed from the viewpoint of modern physiology. As discussed earlier, the increasing association of women with blood depletion reflected the rise of a “positive model of female generativity” in late imperial Chinese medicine. From the seventeenth century on, this model construed female health around symbols of vitality and loss. Chinese physicians considered women to be the “sickly sex” that had a physically (and to some degree emotionally) weak body more prone to sickness due to their constant association with blood loss, such as through childbirth and menstruation.96 In the 1920s and 1930s blood discharge continued to be perceived as the emblematic biological symptom of femaleness. In 1935 Su Yizhen (蘇儀貞) opened her Hygiene Manual for Women with the statement that “menstruation is the most unique physiological difference between men and women.”97 In their book on Women’s Hygiene (1930), Guo Renyi (郭人驥) and Li Renling (酈人麟) also structured women’s life cycle around definitive turning points of menstruation: it is decisively absent before the onset of puberty; its first occurrence marks the girl’s entry into young adulthood; and its permanent cessation marks the beginning of menopause, the final stage of the female life cycle.98 Hence, bioscience universalized femininity by recoding traditional physical markers of blood and menstruation in modern anatomic-physiological terms. As a result, womanhood came to establish itself as the epistemic equivalent of manhood. The introduction of Western biology turned earlier gender signifiers into “natural” sex differences.

The transformation of women’s gender into female sex corroborates feminist theorist Tani Barlow’s assertion that, strictly speaking, “woman” (女性, nüxing) did not exist in China as a universal category before the twentieth century. The closest term available was funü (婦女), which referred to various female subject positions within the discursive network of family, marriage, and kinship. Women were virtuous wives, mothers, daughters, and so on, but they were never identified as a distinct group of individuals outside familial relations. It is interesting to note, for instance, that Chinese gynecology was called fuke (婦科) and not nüke (女科), implying that female bodies of generation and reproduction remained its primary clinical target. Therefore, one of the most reputable legacies of May Fourth feminism was the creation of a generic category of womanhood filtered from its earlier grounding in kin relationality. As Barlow explains it, “Feminist texts accorded a foundational status to physiology and, in the name of nineteenth-century Victorian gender theory, they grounded sexual identity in sexual physiology. Probably the most alarming of all of progressive Chinese feminism’s arguments substituted sexual desire and sexual selection for reproductive service to the jia [family] and made them the foundation of human identity.”99 The shift from the clinical target of fuke to a collective and universal category of sex thus reflected “the passage of women from objects of another’s discourse to women as subjects of their own.”100 An interesting parallel can be found in the context of late colonial India, where the rhetorical reinvention of the woman question, quoting historian Mrinalini Sinha, “offered a new construction of women not as simply saturated by their identification with kin, community, and the nation but, pointedly, as a universal and homogenous gender category.”101

As modernizing elites began to explain gender roles and relations within a Western biomedical lexicon, the images and language of anatomy buttressed a popular vision of sex dimorphism. This turned xing into a dichotomous concept of humanity that manifested itself most tellingly in the physical (sexual) differences between men and women. Consider, for example, the prominent feminist writer Zhang Xichen’s (章錫琛, 1889–1969) remark in 1924: “In the past ten years, there is something most powerful that is developing most rapidly—that is, a shapeless reform in consciousness. This reform is what is called women’s awakening as ‘human beings.’ … Women who had some contact with new thought all have the consciousness that ‘a woman is a human being, too.’ The books which have been regarded women’s bibles, such as Nüjie, Neixun, Nülun, and Nüfan, have all been trampled under the feet of new women.”102

Zhang’s words signaled the formation of an autonomous female subjectivity from the shadow of funü in the new intellectual climate of May Fourth feminism, as womanhood came to be understood no longer in strict congruence with family and kin relations but as the biological representation of half of the human population whose social status ought to be equal to men. This egalitarian view was clearly expressed in 1904 by another pioneer in the women’s movement, Chen Xiefen (陳擷芬, 1883–1923), the daughter of the editor of the radical Shanghai journal Subao: “The inhabitants of China number about four hundred million all together. Men and women each constitute half of this.”103 To borrow Barlow’s insight again, Chinese women “became nüxing only when they became the other of Man in the colonial modernist Victorian binary. Woman was foundational only insofar as she constituted a negation of man, his other.”104

Since the late nineteenth century, Liang Qichao had emphasized the prospect of independent women wage earners contributing to the nation’s economy. But in the years surrounding the New Culture movement, the new discourse of nüxing (meaning biologically sexed woman) proliferated and mainly drew on the ideas of the Western life sciences—an epistemic move away from metaphysics—that would not only define women and female subjectivity in terms of their biology and sexuality but also completely overturn the authority and prestige of neo-Confucian learning.105 According to Leon Rocha, “before it was possible to have a discourse of woman based on her sexual, biological, actual differences (that is, nüxing), sex had to first become human nature through the creation of the neologism xing.”106 In this context, sex/gender, like ethnicity, class, and age, became an important marker of the self.107

The political, social, and cultural factors that motivated Chinese intellectuals, journalists, social reformers, university professors, doctors, and other cultural elites to replace Confucian philosophy with human biology are undoubtedly significant. Their efforts, for instance, cannot be understood as independent of the 1898 reform movement, which had already challenged the imperial institutions and orthodox ideologies in significant ways; the abolishment of the civil service examination system in 1905, which gave women greater access to education; the fall of the imperial polity in 1911; the anti-footbinding and feminist movements; the rise of the printing press; the birth of vernacular Chinese literature; the establishment of modern universities; the consolidation of an intellectual class; and, of course, the resulting famous science versus metaphysics debate in 1923, just to mention a few poignant examples. But “scientism” has often been introduced as a catchall term for rationalizing these interlocutors’ interest in and commitment to the universal value of Western science. On the contrary, my analysis suggests that the universal value that guided these Chinese thinkers was mutually generative of their modernizing optic: the visual objectivity of sex emerged from and critically anchored the earnest production of images of human anatomy, ci and xiong animals, and, as we will see, genes and chromosomes. By making it possible for people to relate what they called xing/sex to a global vision in concrete terms, biomedical science simultaneously affirmed its status as the ultimate arbiter of truth about life and nature in ways that fell outside the tenor of Confucian philosophy or classical Chinese medicine.108 Rather than taking for granted the rhetorical authority of anatomical sex in May Fourth feminist discourse, what I call techniques of visualization helps to explain how and why Western biological notions of sex came to constitute the new epistemological ground for authorizing claims about gender and the body. The visuality of xing further animated new understandings about the subjectivity and mutability of sex, to which we return in the subsequent chapters.

Man and Machine

A parallel historical transformation can be identified in the scientific reconceptualization of manhood. If blood and menstruation were reframed as the most visible cultural indicators of femaleness, the chief “natural” markers of maleness remained sperm and spermatorrhea. In 1925 the Commercial Press published a book, The Sexual Hygiene and Morals of Adolescents, with this inaugurating sentence: “Being the most essential ingredient of health, the internal secretion of the testicles is also known as the ‘inner energy.’ ”109 On the next page the authors reinforced the importance of semen conservation. They cited an example of a male student who could not perform his duties responsibly after having had a “lewd” dream the previous night, which led to “the loss of his essential internal secretions.” “Based on this example,” the authors concluded, “a young man’s physical health is closely related to the natural product of his body.”110

The new vocabulary of bioscience allowed the authors to explain the health implications of semen physiology in a way that would sound nearly incomprehensible to premodern ears: “Teenagers’ secretion will be absorbed by blood, sent to the heart and through the arteries to the muscle fibers; through such a journey, muscles grow and strengthen. When the secreted substance is sent to the brain, it enables the brain to have thoughts, hopes, and expectations and gives the mind evidences of rationality, critical judgment, deep ambitions, strong determination, and rich volition.”111 This interpretation would not have made sense in an earlier period because its logic of reasoning relied on a style of visual imagination—for example, the anatomical representation of muscles and muscularity—that did not exist before the nineteenth century.112 The authors stressed the importance of attaining accurate knowledge about sperm: “Research on the physiological function of sperm is the most important thing, because sperm is the most essential thing in life—it’s the thing that makes someone a father—and the nature of its size makes it almost invisible unless with the help of the microscope.”113 These statements forged a neat coherence between sperm (a Western anatomical concept) and traditional notions of male essence.