Carnal Transformations

A well-known example of the rich cross-cultural interactions between Qing China (1644–1911) and Tokugawa Japan (1603–1867) is the translation of the erotic novel The Carnal Prayer Mat (肉蒲團, Rouputuan) into Japanese in 1705. The name of the author, Li Yu (李漁, 1611–1680), did not appear on the cover of the book, but most critics attribute this erotic comedy to him.1 Written in 1657, only thirteen years after the northern Manchus took over Beijing, the novel is replete with graphic descriptions of the sexual pursuits of the protagonist, Wei Yangsheng (未央生). As the front page of the Japanese translation indicates (figure 3.1), the book was considered by many in the early modern period as “the most promiscuous story in the world” (天下第一風流小說, tianxia diyi fengliu xiaoshuo). The most complete surviving duplication of the original copy is archived at Tokyo University in Japan. Given its explicit content, the book cannot be sold to minors in Taiwan and is still banned in the People’s Republic of China. A quick foray into the text itself provides an important historical preface to unpacking the empirical impulse of sex research in Republican China.

The Carnal Prayer Mat can be situated in the genre of literary pornography similar to the way in which other erotic novels have been perceived in and out of China’s past. The late Ming The Plum in the Golden Vase (金瓶梅, Jin Ping Mei), for instance, which appeared only a few decades before The Carnal Prayer Mat, is perhaps the best example of this kind of literature. What these seventeenth-century erotic novels capture, some observers have argued, is the hedonistic and amoral urban behaviors associated with the growing consumer culture in the waning decades of the Ming.2 Feminist historians and other literary scholars, too, point to the loosening of gender boundaries and sexual mores of the time, as reflected in the blossoming of women’s cultural creativity and alternative arrangements of love and intimacy, especially in the South.3 But the most striking thing about these novels is the considerable degree of popular interest they continue to attract in contemporary Chinese culture. The plots of The Carnal Prayer Mat and The Plum in the Golden Vase have been adapted time and again in the production of new computer games and films, including, most recently, 3-D Sex and Zen: Extreme Ecstasy, a three-dimensional cinematic adaptation of The Carnal Prayer Mat released in 2011.4

Figure 3.1 Front cover of the Japanese translation of The Carnal Prayer Mat (1705).

Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/20/Rouputuan1705.jpg.

If one focuses on the book itself, certain episodes of The Carnal Prayer Mat appear surprisingly queer. Granted, as many critics have pointed out, the story brings a sense of closure to Wei Yangsheng’s erotic adventure, reinstating a normative effect of Confucian discipline through eventual punishment. Having mistreated all the women with whom he had sexual relationships, including his wife, Wei eventually castrates himself and becomes a Buddhist monk to atone for his sins. However, as Angela Zito has suggested, it might be more compelling to foreground Li Yu’s narrative method and the protagonist’s constant subversion of Confucian orthodoxy: “Li Yu presents [the choices of male characters] as the ineluctable outcome of their karmic fates, using against the patriarchal norm, even queering, a Buddhism that, in complex ways, shored up patriarchal familial arrangements in this time.”5

Indeed, the homoerotic contents of the novel are as explicit as the heterosexual ones. After leaving his wife, Wei meets a stranger who would eventually become his close friend, Sai Kunlun (賽崑崙). Spending a night together, naked, Wei insists that Sai share stories of his past sexual encounters with women. Sai accepts the request, and his stories fulfill Wei’s desires: “At this point, it is as if the voice of a promiscuous woman emanates from someone next to Wei, causing his body to tremble. He suddenly ejaculates a dose of semen that he has kept to himself for too long. Unless he is asked otherwise, it is unquestionable what has just happened.”6 Similar to the kind of male–male intimacy that Eve Sedgwick uncovers in English literature, Wei’s homosocial desire for Sai becomes intelligible by being routed through an implicit triangular relation involving women.7 And before he acquires a hugely expanding dog’s penis through surgery, Wei makes love to his sixteen-year-old boy servant one last time.8

Neither the implicitly homoerotic nor the explicitly homosexual scene appears in any of the twentieth-century adaptations of the story. Despite their prominence and wide circulation in contemporary popular culture, the modern versions of The Carnal Prayer Mat and The Plum in the Golden Vase in film and other media are notorious for being consistently marketed as commodities fulfilling the heteronormative desires of men. If one treats these “texts” as immediate historical evidence of sexuality across time, one might be inclined to conclude that homoeroticism “disappeared” in the twentieth century. Or more specifically, the juxtaposition between the seventeenth-century novels (with their frank and open homoerotic depictions) and their modern, more conservative variations seems to suggest a neat discrepancy between the presence of same-sex sexuality before its twentieth-century absence. It is perhaps more accurate to conclude that the afterlife and proliferation of these pornographic texts in the contemporary period rely on an indirect censorship of their homoerotic content. This censorship exemplifies what Sedgwick has called an “epistemological privilege of unknowing,” a successful concealment of certain ways of thinking within the broader structures of knowledge.9 In Sedgwick’s words, “many of the major modes of thought and knowledge in twentieth-century Western culture as a whole are structured—indeed, fractured—by a chronic, now endemic crisis of homo/heterosexual definition, indicatively male, dating from the end of the nineteenth century.”10

Similarly, we can interpret the evolving cultural representation of novels such as The Carnal Prayer Mat and The Plum in the Golden Vase through the lens of this “endemic crisis of homo/heterosexual definition.” By spotlighting the rise of sexology in the 1920s as a pivotal turning point in the history of sexuality in China, this chapter offers an alternative explanation for the disappearance of homoerotic representations in their modern appropriations. After all, what the trajectory of this historical evolution reveals is not so much the coincidental disappearance of homosexuality but its very emergence. With the removal of their homoerotic contents, Ming-Qing erotic texts have essentially become heterosexualized in today’s mass culture. The heteronormalization of The Carnal Prayer Mat therefore points to something more fundamental to the conceptual transformation of sex in the twentieth century: the emergence of its scientific designation as the subject of desire.

Epistemic Modernity

In the previous chapter, I show the ways in which Republican-era biologists and popular science writers translated the epistemological authority of natural science through the production of anatomical, morphological, and chromosomal images of sexual difference. These images affirm a certain form of distance from the viewer, making it possible to decipher truth’s relation to nature through their means of visual objectivation. This chapter explores a different kind of relationship between truth and nature and a different rendition of distance between the subject and object of knowledge. By the 1920s, biological sex had become a commonsense in the popular imagination. With a supporting cast of social commentators, iconoclastic intellectuals began to contend that the hidden nature of erotic preference could also be discovered, deciphered, and known. Sex, they argued, was no longer something only to be seen; it was something to be desired, documented, and diagnosed as well. They participated in a new concerted effort, though not without friction, to emulate the European sexological sciences. Their translation and appropriation of Western sexological texts, concepts, methodologies, and styles of reasoning provided a crucial historical condition under which, and the means through which, sexuality emerged as an object of empirical knowledge. The disciplinary formation of Chinese sexology in the Republican period, therefore, added a new element of carnality to the scientific meaning of sex.

In the aftermath of the New Culture movement (1915–1919), an entire generation of cultural critics promoted sex education and sexological studies in an unprecedented, systematic fashion. Among the famous May Fourth iconoclastic intellectuals, some not only translated texts and adopted methodological rigor from European sexology but also developed their own theories of human sexual behavior and desire. They frequently engaged in heated debates over the meaning, principles, and boundaries of a science of sexuality. In the 1920s and 1930s, they greeted high-profile European sexologists, including Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935) and Margaret Sanger (1879–1966), in major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai.11 During his visit, for instance, Hirschfeld lectured on the development of sexology as a field of scientific research as well as its significance for the practice of medicine, the promotion of feminist causes, and the implementation of sex education (figure 3.2).12 Questions of competence, credentials, expertise, and authority preoccupied those of the early twentieth-century urban intelligentsia who spoke seriously about sex in public. By 1935 disparate efforts and conversations converged in the founding of such monthly periodicals as Sex Science (性科學, Xingkexue). For the first time in China, sexuality was accorded a primacy of scientific “truthfulness.”13

Figure 3.2 Magnus Hirschfeld’s lecture with the Chinese Women’s Association in Shanghai (1931).

Source: Zhi 1931, 298.

This chapter centers on the intellectual journey of two vital figures in this rich tradition of Republican Chinese sexology: Zhang Jingsheng (張競生) and Pan Guangdan (潘光旦). Historians have considered Zhang’s prescription of proper heterosexual conduct as a hallmark of his sexological enterprise, especially as it involved his controversial theory of the “third kind of water.”14 Meanwhile, studies of Pan’s contribution to Chinese sexology have typically focused on his annotated translation of Havelock Ellis’s Psychology of Sex, which grew out of his lifelong interest in promoting eugenics in China.15 Less well studied, however, is their discussion of same-sex desire.16 From the early 1920s on, Zhang and Pan also debated vociferously about each other’s legitimacy as a scientist of sex. Frequently joined by an extended cohort of sex educators and other self-proclaimed experts, such debates reflected the complexity of their sexological maneuver. Moving away from the heteronormative and eugenic emphases of their work, I draw from these examples a snapshot of the broader epistemic context in which the concept of homosexuality emerged as a meaningful point of referencing human difference and cultural identity in twentieth-century China.

Therefore, before we explore scientific discussions of sex change in detail (the topic of next chapter), it is useful to attend to a process of genealogical titration in which the concept of same-sex desire came to be extricated from the broader rubric of gender inversion. The emphasis on homosexuality and the relevant stakes of scientific disciplinarity revises the limited scholarly literature on the history of Chinese sexology. In his earlier study of the medico-scientific constructions of sex, Frank Dikötter argues that early twentieth-century Chinese modernizing elites did not fully grasp or reproduce European concepts of sexual “perversions,” including homosexuality.17 Similarly, Joanna McMillan asserts that, while “sexological studies of perversions were widespread in European medial circles, the literature in Republican China remained almost entirely silent on these enquiries.”18 More recently, in response to Dikötter’s thesis, other scholars such as Tze-lan D. Sang and Wenqing Kang have exposed the ways in which selected May Fourth intellectuals—through various debates in the urban press—actually contributed to the increasing awareness of foreign categorizations of human sexuality in early twentieth-century Chinese mass culture.19

Taken together, these studies tend to depict Republican-era Chinese sexology as a unified field that treated homosexuality merely as a social, rather than a personal, problem.20 According to Kang, for example, “Whereas in the West, sexological knowledge pathologized homosexuality as socially deviant, thus reducing it to an individual psychological problem, in China sexology as a form of modern knowledge was used more to diagnose social and national problems.… As Chinese writers and thinkers introduced Western sexology to China, male same-sex relations were stigmatized more as a disruptive social deviance than a personal medical condition.”21 Sang’s analysis, too, seems to support the claim that no effect similar to the European “individualization” of homosexuality took place in Republican China. In the context of the May Fourth era, Sang observes, “tongxing ai [‘same-sex love’] is primarily signified as a modality of love or an intersubjective rapport rather than as a category of personhood, that is, an identity.”22

In this chapter, I suggest that this interpretation is an oversimplification. The view that homosexuality was only a social problem was not consistently shared by leading sexologists from the period, such as Zhang Jingsheng and Pan Guangdan. In the process of establishing sexuality as an appropriate object of scientific inquiry, they deliberated different opinions about the etiology, prevention, and significance of same-sex love. They even disagreed on the fundamental principles of sexological research. Given the multiple perspectives competing at the time, it is perhaps more compelling to suggest that homosexuality appeared to Chinese experts and popular audiences as much a personal problem as it was a social one—an explicit issue of personhood, subjectivity, and identity. Open communications between “sexperts,” their readers, and other sexperts further enriched this incitement of a discourse that found truth in sex. To borrow Michel Foucault’s insight on the incitement to speak about sex in modern bourgeois society, “Whether in the form of a subtle confession in confidence or an authoritarian interrogation, sex—be it refined or rustic—had to be put into words.”23 Sexology in Republican China was indeed a new system of knowledge in which, literally, new subjects were made.

Ultimately, participants of this new discourse established for China what Foucault has called scientia sexualis, which first distinguished itself in nineteenth-century Europe: a new regime of truth that relocated the discursive technology of the sexual self from the theological sphere of pastoral confession to the secular discourses of science and medicine.24 I argue that from the 1920s through the 1940s, the conceptual space for articulating a Western-derived homosexual identity emerged in China precisely from the new regime of truth oriented by the introduction of European-type sexology. Moreover, whereas social scientists Dennis Altman, Lisa Rofel, and Judith Farquhar have respectively claimed that “gay identity” and scientia sexualis first appeared on the China scene only by the post-socialist era, my historicization suggests that both have deeper roots that can be traced to an earlier turning point—in the Republican period.25

Part of my divergence from these previous studies seems to stem from the absence of a theoretical vocabulary that fully registers the complexity of sexological claims in this period. Chinese sexologists’ conviction that Western science held the key to effective modernization suggests that claims about tradition and modernity were embedded within claims of sexual knowledge. Though distinct, these two layers of the production of sexual truth are somewhat confounded in the analyses of Dikötter, Sang, and Kang: for them, sexological research on homosexuality in the Republican period itself marked a condition of modernization rather than a condition that permitted further referential points of argumentation about the authenticity, traditionality, and modernity of Chinese culture. This conflation rests on the assumption that broader trajectories of historical change—such as modernization and nationalization—are taken for granted and more immediately relevant to the emergence of a discourse of sexology in Republican China. But what if the stakes of the formation of such a discourse depended as much on these broader processes of historical change as on its internal disciplinary tensions and epistemic frictions? As generations of science studies scholars have shown, such conflicts and dissonances are crucial to the consolidation of any kind of scientific valuation.26

In order to differentiate the two levels of truth production on which sexological claims operated, this chapter proposes and develops the analytic rubric of epistemic modernity. My application of epistemic modernity in the following analysis refers to an apparatus in the Foucauldian sense that characterizes a historical moment during which a new science of sexuality became epistemologically rooted in Chinese culture. In the next section, I make even more explicit the historiographical rationale for implementing this theoretical neologism, including an operational definition appropriate for the purpose of this study. The core of this chapter consists of three interrelated sections, each featuring an aspect of epistemic modernity. Together they help to reveal a macro, multidimensional picture of East Asian scientia sexualis: the creation of a public of truth in which the authority of truth could be contested, translated across culture, and reinforced through new organizational efforts constitutes the social-epistemic foundation for the establishment of sexology in Republican China. I conclude by coming back to the central issue of how homosexuality emerged as a meaningful category of experience in this context. Its comprehensibility, I argue, depends on a new nationalistic style of argumentation that arose from the interplay between the introduction of a foreign sexological concept and the displacement of an indigenous understanding of same-sex desire.

Thresholds of Scientificity

Talking about (male) homoeroticism in China, one first thinks of its rich cultural history prior to the twentieth century, an ongoing topic of in-depth scholarly discussion.27 This history, however, is not static but dynamic: over the years, the social significance of same-sex relations in dynastic China evolved according to the relevant historical factors. As Matthew Sommer’s work on Chinese legal history has shown, sodomy appeared as a formal legislation in China only by the late imperial period. During the eighteenth-century Yongzheng reign (1723–1735), male same-sex practice was for the first time directly “assimilated” to heterosexual practice under the rubric of “illicit sex.” This Qing innovation fundamentally reoriented the organizing principle for the regulation of sexuality in China: a universal order of “appropriate” gender roles and attributes was granted some foundational value over the previous status-oriented paradigm, in which different status groups were expected to hold unique standards of familial and sexual morality.28 But whether someone who engaged in same-sex behavior was criminalized due to his disruption of a social order organized around status or gender performance, the world of imperial China never viewed the experience of homosexuality as a separate problem.29 The question was never homosexuality per se but whether one’s sexual behavior would potentially reverse the dominant script of social order. If we want to isolate the problem of homosexuality in China, we must jump to the first half of the twentieth century to find it.

The relationship between forms of experience and systems of knowledge thus occupies a central role in this historical problem, if only because what we have come to call “sexuality” is a relatively recent product of a system of medico-scientific knowledge that has its own unique style of reasoning and argumentation.30 In the European context, sexuality emerged from the new conceptual space conditioned by the nineteenth-century shift from an anatomical to a psychiatric style of medical reasoning. “Before the second half of the nineteenth century,” according to philosopher Arnold I. Davidson, “Anatomical sex exhausted one’s sexual identity” because “the anatomical style of reasoning took sex as its object of investigation and concerned itself with diseases of structural abnormality.” Hence, “as little as 150 years ago, psychiatric theories of sexual identity disorders were not false, but rather were not even possible candidates of truth-or-falsehood. Only with the birth of a psychiatric style of reasoning were there categories of evidence, verification, explanation, and so on, that allowed such theories to be true-or-false.” “Indeed,” Davidson claims, “sexuality itself is a product of the psychiatric style of reasoning.”31 The historical specificity and uniqueness of sexual concepts cannot be overstated, especially since our modern formulation of homosexuality, as the classicist David Halperin reminds us, does not anchor on a notion of object choice, orientation, or behavior alone but “seems to depend on the unstable conjunction of all three.”32

If understanding the historical relationship between sexuality and knowledge claims in the Western context requires such careful historicism, zooming in on East Asia entails at least one additional layer of consideration. Since the mid-nineteenth century, the medical landscape in China had been characterized by an increasingly conspicuous struggle to reconcile the existing canon of indigenous Chinese medicine with foreign Western biomedical knowledge. For instance, as the last chapter has shown, Benjamin Hobson’s anatomical drawings represented a radical epistemological departure from conventional theories of the sexual body in Chinese medicine. The heterogeneous efforts to bring together two coexisting but oftentimes competing systems of medical epistemology were overwhelmingly articulated within a larger sociopolitical project conceived in terms of nationalism.33 Ideas and practices of nation making would come to assume the center stage in Chinese political and cultural discourses, especially following the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895). To ask the very least, why did modernizing thinkers like Zhang Jingsheng, Pan Guangdan, and other sex researchers use Western sexological ideas rather than traditional Chinese medical theory to purport a style of reasoning that stigmatized same-sex desire? What are the deeper historical implications behind such intellectual priorities? The relationship between systems of knowledge and notions of modernity in East Asia demands problematization as we historicize the concept of homosexuality—or, for that matter, sexuality—itself. In order to carefully account for the historical condition under which homosexuality became a meaningful Chinese category, we need a more potent historiographical framework for analyzing the relationship between science and sexuality in twentieth-century China.

To that end, I find what I call epistemic modernity, which builds on historian Prasenjit Duara’s notion of “the East Asian modern,” particularly useful. When proposing the idea of the East Asian modern in his groundbreaking study of Manchukuo, Duara aims to address two concomitant registers of historical production: how “the past is repeatedly re-signified and mobilized to serve future projects” and the transnationality of “the circulation of practices and signifiers evoking historical authenticity in the region.” The concept allows Duara to treat “the modern” as a “hegemonic” project, “a set of temporal practices and discourses that is imposed or instituted by modernizers … rather than a preconstituted period or a given condition.”34 The emergence of homosexuality in early twentieth-century China adduces a parallel moment of contingent historicity. The analytic lens of epistemic modernity allows us to see homosexuality not as a strictly “modern” category but as a by-product of a contested historical process yielding specific cultural associations with the traditional, the modern, and the authentic.

Focusing on similar aspects of the transnational processes, flows, and interactions of regimes of cultural temporality and specificity in East Asia, my notion of epistemic modernity refers to a discursive apparatus of knowledge production that also governs implicit claims of traditionality, authenticity, and modernity: it essentially defines the index of imbrication in people’s simultaneous preoccupation with the epistemology of scientific deliberation and the procedural determination of what counts as traditional, authentic, or modern. The analytic rubric enables a perspective on the historical question of, to cite Tani Barlow from a different context, “how our mutual present came to take its apparent shape” in “a complex field of relationships or threads of material that connect multiply in space-time and can be surveyed from specific sites.”35 As such, epistemic modernity does not merely denote a system of knowledge; rather, it features a set of ongoing practices and discourses that mediates the relationship between systems of knowledge (e.g., Chinese or Western medicine) and modalities of power (e.g., biopower) in yielding specific forms of experience (e.g., sexuality) or shaping new categories of subjectivity (e.g., homosexual identity). Modernity, to borrow the words of cultural critic Kuan-Hsing Chen, is therefore “not the normative drive to become modern, but an analytical concept that attempts to capture the effectiveness of modernizing forces as they negotiate and mix with local history and culture.”36

By treating traditionality and authenticity as not ontologically given but constructed as such through the ongoing modernizing technologies of nationalistic measures, I thus attempt to offer sharper insights concerning the regional mediation of globally circulating discourses, categories, and practices in twentieth-century East Asia. The history of homosexuality in China, based on this model, is a history of how globally circulating categories, discourses, and practices were mediated within that particular geobody we call “China.” A major aim of this chapter is to show that, in the context of early twentieth-century China, homosexuality was precisely one of these categories; sexology exemplified this kind of discourse; and the articulation of a Western psychiatric style of reasoning about sexuality represented one such practice. A relevant case in point is Ruth Rogaski’s study of “hygienic modernity,” for one can understand the hygiene–public health nexus as an exemplary model of how globally circulating discourses (of hygiene) and practices (as promulgated by public health campaigns and state interventions) were mediated by the discursive apparatus of epistemic modernity in the historical formation of national Republican China.37

Whether our analytic prism is sexuality or hygiene, epistemic modernity affords an opportunity to take the growing global hegemony of Western conceptions of health and diseases seriously without necessitating a full-blown self- or re-Orientalization. By that I mean an intentional project that continually defers an “alternative modernity” and essentializes non-Westernness (including Chineseness) by assuming that the genealogical status of that derivative copy of an “original” Western modernity is somehow always already hermeneutically sealed from the historical apparatus of Westernization.38 Now that studies in the history of sexuality in non-Western regions have begun to mature, historians should be even more (not less) cautious of any effort to view the broader historical processes of epistemic homogenization as having any lesser bearing than forms of local (or “Oriental”) resistance.39 The idea that “local” configurations of gender and sexuality cannot be overridden by modern Western taxonomies of sexual identity is by now a standard interpretation of both the historical record and the cultural archive of non-Western sexualities. But a variant of this interpretation has already generated vehement repercussions in the field of Middle Eastern studies. Consider intellectual historian Joseph Massad’s controversial claim that all social significations of homosexuality, including internal gay rights activism, reflect the growing infiltration of Western cultural imperialism: “The categories of gay and lesbian are not universal at all and can only be universalized by the epistemic, ethical, and political violence unleashed on the rest of the world by the very international human rights advocates whose aim is to defend the very people their intervention is creating.”40 It bears striking similarity, however ironically and uncomfortably, to Lisa Rofel’s adamant critique of a “globalized gay identity.”41 Whether the target of critique is global gay or global sex, post-Orientalist critical thinking should not deter the historian’s interest in the condition of the translatability of sexual concepts, especially since the very same concepts have been invoked repeatedly by historical actors themselves.

To redress these analytical conundrums concerning the relationship between transnationalism and sexuality from a strong historicist viewpoint, what I am concerned with, then, is not a social history of homosexuals in China “from below,” but an epistemological history in the Foucauldian sense that “is situated at the threshold of scientificity.”42 In other words, this is a study of “how a concept [like homosexuality]—still overlaid with [earlier] metaphors or imaginary contents—was purified, and accorded the status and function of a scientific concept. To discover how a region of experience [such as same-sex intimacy] that has already been mapped, already partially articulated, but is still overlaid with immediate practical uses or values related to those uses, was constituted as a scientific domain.”43 The rest of this chapter is devoted to examining closely the historical conditions under which the concept of same-sex desire came to fall within the realm of Chinese scientific thinking. Each of the following sections features an aspect of the cultural apparatus that I call epistemic modernity: a public of truth, a contested terrain of authority, and an intellectual landscape of disciplinarity. Each distinguishes the two levels of truth production on which sexological claims operated: one concerning explicit claims about the object of scientific knowledge (e.g., sexuality), and another concerning implicit claims about cultural indicators of traditionality, authenticity, and modernity (e.g., ways of narrating sex). Operating together within the governing apparatus of epistemic modernity, they anchored the ways in which same-sex sexuality crossed the threshold of scientificity and the very foundations upon which a scientia sexualis grappled the cultural context of Republican China.

Making Truth Public

No other point of departure serves the purpose of our inquiry better than the sex-education campaign that began to acquire some formality in the 1920s. In order to turn sex into a legitimate object of scientific inquiry and education, a notable segment of the urban intelligentsia drew on ideas from Western natural and social sciences. These discussions occurred in university lecture rooms, health care settings, public debates, and both the mainstream press and the vernacular print culture, including the newly established periodicals that featured explicit coverage of sex-related matters, such as New Women (新女性, Xinnüxing), New Culture (新文化, Xinwenhua), Ladies Journal, Sex Magazine (性雜誌, Xingzazhi), Sex Science, and West Wind (西風, Xifeng) (figures 3.3 and 3.4). In these forums, pedagogues, doctors, scientists, social reformers, cultural critics, and other public intellectuals taught people how to think about sexuality in scientific terms. In the years following the Xinhai Revolution and surrounding the New Culture movement, they viewed open talk about sexual behavior and desire as a sign of liberation. Or, to borrow the term from D. W. Y. Kwok’s classic study, they squarely situated this frankness in the outlook of a new “scientism”—defined as “that view which places all reality within a natural order and deems all aspects of this order, be they biological, social, physical, or psychological, to be knowable only by the methods of science”—that characterized Chinese culture in the first half of the twentieth century.44

Figure 3.3 Front cover of Sex Magazine 1, no. 2 (1927)

Source: Xing zazhi (性雜誌) [Sex magazine] 1, no. 2 (1927).

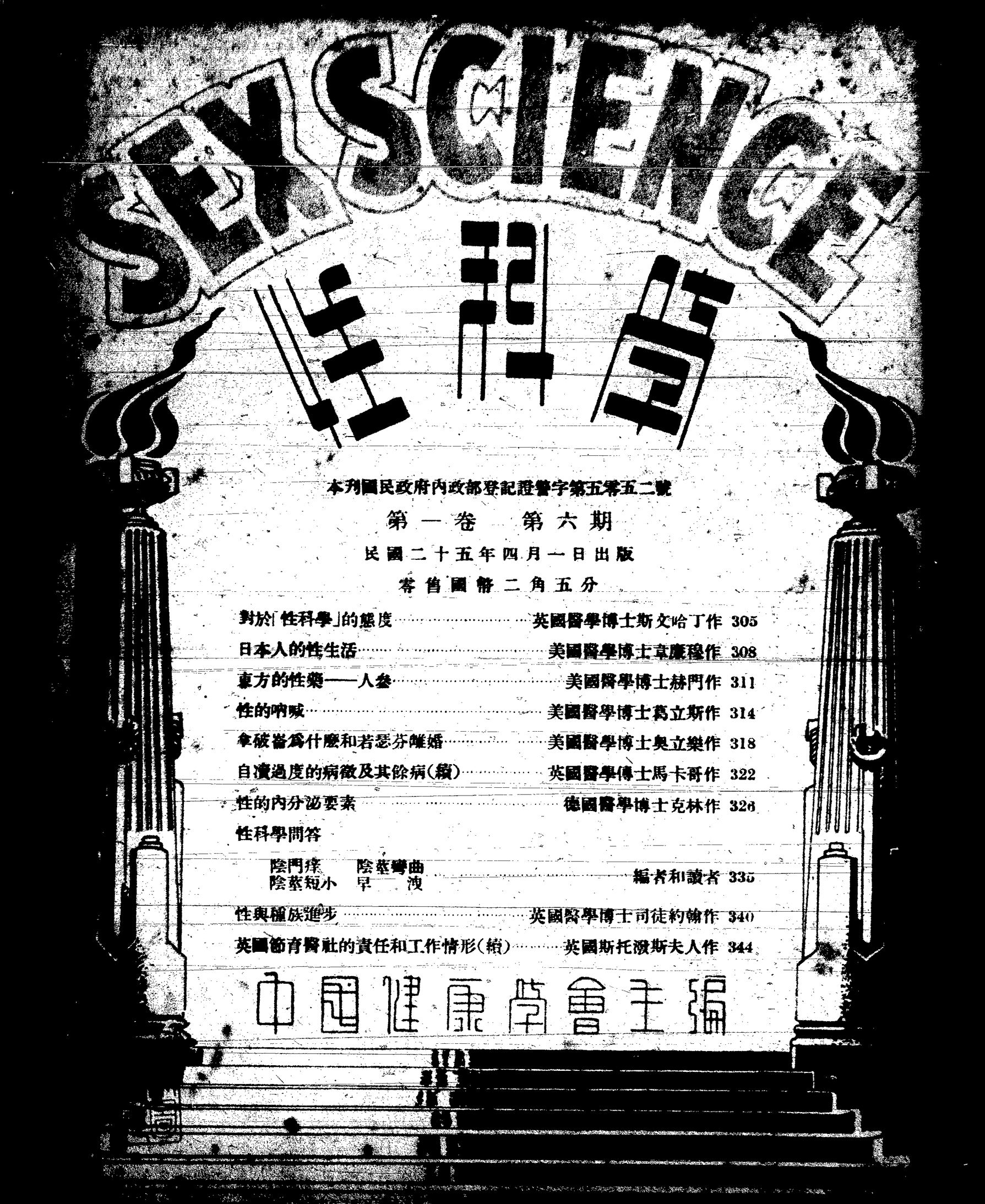

Figure 3.4 Front cover of Sex Science 1, no. 6 (1936).

Source: Xing kexue (性科學) [Sex science] 1, no. 6 (1936).

In the 1920s many sex pedagogues considered adequate sex education vital for unveiling the puzzling phenomenon of homosexuality. In a lead essay in the inaugural issue of Sex Magazine, “The Necessity of Sex Education” (1927), Wu Ruishu (吳瑞書) argued that sexuality (性慾, xingyu) should be a topic of weighty discussion because it represented one of the most fundamental human urges that helped to “protect the race” and “ensure human survival.” According to Wu, if the subject of sexual desire was prohibited from bold and direct dialogue, it would exacerbate public confusion over such social problems as women’s criminal behavior and homosexuality, the latter being rampant in school settings.45 A more extreme, yet rather common, view of the role of sex education in disseminating knowledge about homosexuality can be found in an article titled, “A Paramount Problem in Sex Education: Some Reflections on Homosexuality” (1922), by Li Zongwu (李宗武). Li contended that sex education should caution young people of the danger of homosexuality, presenting it as a form of “sexual aberration” (性的畸形發達, xingde jixing fada) and the root of many unnecessary tragedies in life. He encouraged jettisoning the value placed on gender segregation in traditional Chinese society. According to him, separating the two sexes cultivated homosociality, which would in turn strengthen “unnatural” homosexual desires and weaken “natural” heterosexual bonds. By raising public awareness about the undesirability of homosexuality and by promoting mixed-sex interactions among young adults, he believed that the occurrence of homosexual love—which he contrasted with “platonic love” (純潔愛, chunjieai)—could be curtailed.46 In 1926 Qiu Jun (丘畯), a biologist at the Nationalist-funded Guangdong University, identified many examples of homosexuality in the animal kingdom, a phenomenon he attributed to the outnumbering of xiong (male) by ci (female) animals in general. Echoing Li’s sex-education agenda, Qiu believed that the best way to prevent animal homosexuality was to provide ci and xiong animals a congenial environment for their sexual expression and to breed a higher number of xiong animals.

In the context of growing support for sex education, foreign scientific ideas about sex and sexuality met with considerable enthusiasm. Public spokesmen who took the initiative to translate and disseminate Western psychobiological concepts typically received their advanced degrees at European, American, or Japanese institutions. Upon returning from abroad, many of them shared the conviction that adequate sex education was important for the strengthening of the nation, a belief intimately linked to the broader cultural ambience of the May Fourth movement. According to Frank Dikötter’s observation of this period, “For the modernizing élites in Republican China, individual sexual desire had to be disciplined and evil habits eliminated, and couples were to regulate their sexual behaviour strictly to help bring about the revival of the nation.”47 By setting up the British sexologist Havelock Ellis as a role model, many of these modernizing elites singled out his seven-volume encyclopedic Studies in the Psychology of Sex as the epitome of scientific research on human sexuality. One of the foremost modernizing thinkers who emulated the empirical impulse of Ellis’s work was China’s own “Dr. Sex” (性博士, xingbuoshi), Zhang Jingsheng.

A university professor and a sex educator, Zhang Jingsheng treated his own sexological treatise, Sex Histories (性史, Xingshi), as a Chinese counterpart to Ellis’s Studies. After earning his doctorate in philosophy from Université de Lyon, Zhang returned to China in 1920 and initially taught at the Jingshan Middle School in Guangzhou. For being educated abroad, Zhang was very much part of the work-study movement promoted by the French and Chinese governments in the 1910s. Although part of the initial rationale for this “work-study programme” was to popularize education and dissociate it from cultural elitism, by the end of the decade, the program was soon associated only with those who were anxious to study abroad. Not surprisingly, many of these individuals actually came from a family background that was fairly well-off. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, however, most students studying overseas actually went to either the United States or Japan.48 Zhang’s decision to study in France allowed him to maintain close ties with important figures such as Wang Jingwei (汪精衛, 1883–1944), Wu Yuzhang (吳玉章, 1878–1966), Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培, 1868–1940), and Li Shizeng. With these anarchists of the Nationalist party, Zhang participated in the founding of the Sino-French Education Association, branches of which, by 1919, could be found in Shanghai, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Hunan, Shandong, and Fujian.49

Zhang’s participation in the association and the early work-study movement significantly shaped his intellectual orientation. When he was forced to resign from his post at the Jingshan Middle School in 1921, Cai Yuanpei offered him a teaching position at Peking University, the epicenter of the May Fourth movement. Throughout the second half of the 1910s, the Sino-French Education Association actively promoted the view that overseas study in France offered a rare opportunity for Chinese people to learn European science and humanist thinking without entirely relying on Japan. Adopting this vision, Zhang saw in Cai’s offer to teach at Peking University at the peak of the May Fourth a unique opportunity to enlighten the Chinese public about sex. His first two books, A Way of Life Based on Beauty (美的人生觀, Meide renshengguan; 1924) and Organizational Principles of a Society Based on Beauty (美的社會組織法, Meide shehui zuzhifa; 1925), expressed his conviction that the Chinese nation should be strengthened by learning from Europe, the United States, and Japan, especially on the topics of economic structure and military organization. Championing positive eugenics, Zhang even encouraged interracial marriage (and procreation) between Chinese people and those races that possessed strength where the Chinese race was weak, including the Europeans, Americans, Russians, and even the Japanese.50

Following these two well-received books, Zhang’s publication of Sex Histories in 1926 earned him the popular title “Dr. Sex.” In fact, he had been lecturing on human sexuality regularly at Peking University since September 1923.51 Sex Histories comprised seven life histories written in the form of first-person narrative by those who responded to Zhang’s “call for stories,” which was originally published in the supplemental section of the Capital Newspaper (京報, Jingbao) in early 1926. This “call for stories” was titled “A Way to Kill Time for the Winter Vacation,” and it asked young people to contribute stories and any other relevant, however mundane, information about their sex lives. It also indicated that these stories would be “psychoanalyzed” and serve the purpose of a “hygienic” intervention.52 Zhang studied these life histories carefully and provided commentaries after each of the stories he included in Sex Histories. Therefore, Zhang’s book adopted a case-study format similar to the way Western sexologists typically organized and presented their research finding.

Indeed, when Zhang published Sex Histories, he assiduously advertised the book as “a piece of science, because it documents facts.”53 In his view, there was nothing obscene or inappropriate about his effort to compile a volume based on people’s accounts of their sexual thoughts and behaviors. After all, this documentation method had preoccupied European psychiatrists and other forensic doctors for decades already, although their focus had been primarily on deviant sexual expressions.54 “To keep a strict record of how things happened in the way they did is the kind of mindset that any scientist should have,” Zhang insisted.55 He ended the book with a reprint of the “call for stories” entry, which also solicited collaborators for a project that he had envisaged on translating Ellis’s Studies.56 In a word, Zhang considered what he was doing in China to resemble what the European sexologists were doing on the other side of the world.57

Zhang’s appropriation of Western sexological empiricism—as exemplified by the effort to collect case studies and “document facts”—illustrates a straightforward example of epistemic modernity: implicit in his self-proclaimed expertise on human sexuality lies a claim of another sort concerning referential points of tradition and modernity in Chinese culture. In Zhang’s sexological project, knowledge about sexuality involved a modern phenomenon of narrating one’s life history in a truthful manner. Whereas literature (e.g., fiction, poetry) had been the traditional vehicle for the cultural expression of love and intimacy (including homoeroticism) in late imperial China, according to Zhang’s sexology, this mode of representation was no longer appropriate in the twentieth century.58 His empirical methodology posited a new way of confessing one’s erotic experience in the name of science, the domain of modernity in which the truthfulness of sexual desires was to be recorded, investigated, and explained. Similar to the ways in which “sex was constituted as a problem of truth” in nineteenth-century Europe, the procedure for producing sexual knowledge promulgated by Zhang transformed personal desire into scientific data: “sex was not only a matter of sensation and pleasure, of law and taboo, but also of truth and falsehood.”59

By encouraging people to talk about their sexual experiences in a new order of knowledge that conformed to the “norms of scientific regularity,” Zhang hoped to achieve more than just archiving “the facts of life.”60 As the “call for stories” makes clear, narrators who were brave enough to speak out and report their sex life were rewarded with the unparalleled opinion of a sexpert, who, according to the entry, possessed the kind of enlightening scientific knowledge about sexuality from which laypersons could learn and benefit. So, drawing on his academic training in philosophy and the empirical approach of European sexologists, Zhang framed the modernism of his sexological science with another epistemological tool: theoretical innovation. He did this by developing a coherent set of guiding principles in human sexual conduct based on concepts of Western bioscience.

His theory of a “third kind of water” is perhaps the most famous and controversial example. According to this theory, the female body produces three kinds of water inside the vagina: one by the labia, another by the clitoris, and a third from the Bartholin glands. The release of all three kinds of water, especially the “third kind,” during sex would benefit the health and pleasure of both partners. Reflecting its eugenics underpinning, the theory claims that the release of this “third kind of water” at the right moment, which normally means twenty to thirty minutes into sexual intercourse as both partners achieve simultaneous orgasm, is crucial to the conception of an intelligent, fit, and healthy baby.61 At least one other self-proclaimed sexpert, Chai Fuyuan, author of ABC of Sexology, supported Zhang’s idea of female ejaculation.62

Interestingly, apart from construing women as active agents in heterosexual intercourse (e.g., by asking them to perform “vaginal breathing”), Zhang also held them responsible for reducing male homosexual behavior in China.63 In Sex Histories, for instance, Zhang reasoned that since the anus lacked “momentum” and any kind of “electrolytic qi,” it could not compete with the vagina, which was filled with “lively qi.” As long as women took good care of their vagina and used it properly for sex, such as by complying to his theory of the “third kind of water,” the “perverted,” “malodorous,” “meaningless,” and “inhumane” behavior of anal intercourse among men could be ultimately eliminated.64 This example powerfully illustrates the subtle ways in which male same-sex practice came to be discussed in the language of biological science: although not the direct cause of homosexuality per se, according to Zhang’s theory, the properties, quality, and physiological mechanism of female reproductive anatomy were nonetheless understood as a key determinant of the prevalence of male homosexual conduct. Meanwhile, in prioritizing Western biology as a modernist discourse for the cultural appreciation of female heterosexuality, his theoretical project construed Daoist alchemy as a symbol of tradition in conceptions of sexual health in Chinese culture.

Zhang, above all, sought to create a new public of truth about sex. By privileging the scientific public as the ultimate site for sexual understanding and narration, his effort made unproblematic a discourse based on reason to speak of sex. The autobiographical narratives that he collected in Sex Histories strictly cohered around this vision. Additionally, in his capacity as the founding editor of the popular magazine New Culture, he published translations of excerpts from Ellis’s Studies in the Psychology of Sex. The periodical soon became a venue for other kindred spirits to present the science of sexology to a popular audience and to establish their own “sexpertise.” But most importantly, New Culture was not a forum devoted exclusively to the voice of experts; it published readers’ responses to not only its most controversial essays but also any contemporary issue that seemed relevant to the scope of the magazine, including sex-related subjects. In the pages of New Culture, “the speaking subject [was] also the subject of the statement.”65

Readers, presumably many of whom resided in urban areas where the mass circulated print publications were most readily accessible, seized the opportunity to respond to Zhang’s provocative writings. Some felt the need to confirm the scientific value of his work. One reader, for example, interpreted Sex Histories as an “outstanding scientific piece of ‘sex research.’ ”66 Another reader urged him to publish more sexological treatises like Sex Histories by asking “why have you published only one volume of Sex Histories? Have you met your goal with this singular contribution?”67 Others similarly maintained that Sex Histories “definitely cannot be viewed as a pornographic piece of writing. Its contents are all valid research material on sexual activities.”68

Some readers did not find it necessary to justify the scientific nature of Dr. Sex’s advice. From the outset many took for granted that his words already constituted science. One woman wrote to Zhang:

There is one part of your advice that said “the female partner should try to become excited, so that there will be a great amount of water released in the vagina. The male partner could then gradually insert his penis into her vagina … and rub it back and forth smoothly and easily.” This part, I think, is a little too idealistic. In fact, it cannot be accomplished: although I am a woman who has been married for over a year, if I follow your suggestion, I think it certainly will not work. This is because people who are impatient, men or women, would quickly lose sexual interest in the process. As for those who prefer to take their time, they probably would start getting tired and annoyed of the process, and this might even have a negative effect on two persons’ love for each other. What do you think?69

Although disagreeing with Zhang’s initial advice, this reader still considered him the ultimate authority on matters pertaining to sex. In fact, the letter squarely conveyed her desire to contribute to Dr. Sex’s science by providing a personal perspective, which bore a similar empirical value to the case studies collected in Sex Histories. Another reader named Xu Jingzai (徐敬仔) even offered Zhang his own insight concerning the proper way of “sexual breathing.”70 Others similarly respected what Zhang had to offer but either wanted to learn more about his theory of the “third kind of water” from the perspective of men or expressed frustration with its impracticality based on their own experience in the bedroom.71

A number of readers directly responded to Dr. Sex’s brief discussion of homosexuality. Supporting Zhang’s effort in promoting sex education on scientific grounds, a lady named Su Ya (素雅) argued that the prevalence of undesirable sexual practice would decrease once adequate sex education became common in China. Su wrote to Zhang by echoing the ambition of many sex educators: “As long as sex education continues to be promoted and advanced, all the illegal sexual behaviors, such as rape, homosexuality, illegal sex, masturbation, etc., could be eliminated.”72 Miss Qin Xin (芹心), however, disagreed: “Homosexuality is not a natural sexual lifestyle. It is a kind of perversion and derailment in human sexuality, so it does not have a proper place in sex education.”73 Another reader asked, “It seems that homosexuality exists among both men and women, but could these people’s ‘sexual happiness’ be identical to the kind of enjoyment experienced in sexual activities with the opposite sex?” Zhang answered with a blatant no: “Other than being a personal hobby, homosexuality cannot compare to the kind of happiness one achieves in heterosexual intercourse. Since on the physical level it cannot generate the kind of electric qi found in heterosexual mutual attraction, homosexuality also does not provide real satisfaction on the psychological level.”74 Zhang’s response thus reminded his readers the importance of knowing and practicing the correct form of heterosexual intercourse. It implied the paramount significance of following his theory of the “third kind of water,” which defined women’s befitting sexual performance, attitude, and responsibility.

Together the guidelines that Zhang offered in Sex Histories and his communications with readers in New Culture shed light on the grounding of sexological science in Republican China through the means of expert intervention. To borrow Foucault’s insight on this matter again, it was a technology of power in which “one had to speak of sex; one had to speak publicly and in a manner that was not determined by the division between licit and illicit … one had to speak of it as of a thing to be not simply condemned or tolerated but managed, inserted into systems of utility, regulated for the greater good of all, made to function according to an optimum. Sex was not something one simply judged; it was a thing one administered.”75 Starting in the 1920s, under the influence of Dr. Sex, some Chinese urbanites began to treat heterosexuality and homosexuality as scientific categories of discussion and sexology as a serious discourse of expertise knowledge. In 1927 one individual who worked for the Fine Arts Research Society (美術研究會, Meishu yanjiuhui) observed that “due to the recent progress in academia, there is a new independent scientific field of study that surprises people. What kind of science is it? It’s called sexology.”76 In particular, Zhang Jingsheng’s theory of the “third kind of water” both biologized and psychologized sex. It biologized sex because it discussed people’s erotic drives and motivations in terms of the somatic functions of male and female reproductive anatomy. The theory psychologized sex by explaining people’s sexual behavior and activities in terms of what they thought and how they felt.

The case studies approach advocated by Dr. Sex marked a decisive turning point in Chinese sexology. This empirical signature gradually came to characterize the entire scientific discourse of homosexuality in the Republican period. This was especially true for writings on female same-sex intimacy. In the scattered commentaries on the subject that appeared in the urban press before the time of Dr. Sex, the case studies format was notably absent. In one of the earliest Republican-era accounts of female homosexuality, for example, the author Shan Zai (善哉) introduced the concept of “sexual inversion” (情慾之顛倒, qingyu zhi diandao) and commented on its prevalence as documented in the historical record worldwide. However, she never mentioned a single concrete case, leaving the tone of her overview general and abstract.77 In 1923 a contributor to the Ladies Journal explained homosexuality as a consequence of gender segregation in education and military settings. Again, the author did not discuss in depth an actual homosexual affair in these unisex institutions. Referencing Western psychological theories of marriage, the author merely upheld the value of mixed-sex education.78 The translation of a Japanese article on the implication of homosexuality for women’s education appeared two years later in the same journal. Although the article brought up Oscar Wilde’s trial in England, specific cases of homosexuality in contemporary East Asian society appeared nowhere in this piece. Interestingly, unlike most of the essays printed at the time, this article challenged a stigmatized understanding of homosexuality and pushed for a more sentimental definition by drawing on the theories of the British sexologist Edward Carpenter (1844–1929).79

After Zhang published Sex Histories, the majority of popular writings on female homosexuality included actual “cases” as examples. These publications were often billed with an “objective” voice, imitating the sexological authority of Dr. Sex, and with the intention to cast light on new anecdotes of homosexual relations between women. An article in New Ladies Monthly, titled “Homosexuality” (1946), opened with two stories of lesbian love. The first story involved two students who always spent time together in their daily routines, from having meals together to sitting next to each other in classrooms. As their relationship grew, one of them became an object of affection to a third classmate, leading the other to cultivate a strong sense of jealousy. The envious girl therefore attempted to stab her lover although, as it turned out, without success. The second story was about the intense romance between a masculine “Miss S” and a feminine “Miss Y.” Given their attachment, the sexual nature of their relationship was unambiguous to their peers. Eventually, Miss S acquainted herself with a male partner, and, depressed in consequence, Miss Y tried to convince Miss S to commit suicide with her. This tragedy was avoided when a friend introduced Miss Y to another male date, and both Miss S and Miss Y got married separately. These two specific cases provided the empirical basis for the author of the article to use scientific theories of sexual psychobiology to explain this “perverse sexual desire” (變態性慾, biantai xingyu). The narratives thereby anchored a broader discussion of “the prevalence of these kinds of story in Chinese unisex schools before the Japanese occupation period” and how the popularity of free love made the cultural context at the time especially congenial for developing homosexual tendencies.80

Other writers contributed to the empirical understanding of lesbianism by proposing that it was regionally specific—a situation endemic to the South. In 1934 Jian Yun (澗雲) documented the few cases of lesbianism that she personally witnessed in a two-part essay published in the Shanghai-based Choumou Monthly (綢繆月刊). Specifically, she substantiated two stories in detail. The first story occurred in 1922, the year when she arrived in Hong Kong to stay with a female friend, W, who cohabitated with another lady, S. Jian Yun compared their residence to the kind of living arrangement typical of a conventional married couple. Although she slept on the same bed with W and S for the first two nights, Jian Yun decided to leave them on the third day and went to stay with her cousin instead. Years later, she discovered that both W and S got very sick and were hospitalized for several weeks. S eventually married a man, and the couple moved to the Philippines. W, on the other hand, refused to compromise and so still clung onto the past.81 The second, much more convoluted story featured her coworker, L from Nanhai (a district of Foshan, Guangdong), and L’s mother. Both L and L’s mother, so Jian Yun’s report suggests, were enticed into being romantically involved with other women, causing both to experience serious illness involving menstrual irregularities and eventually death.82 Jian Yun presented these stories as examples of the kind of lesbianism recurrent in Southern China, especially in Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Nanhai, among other regions.83

Additional stories came from lesbians themselves. These tended to be couched in a more “subjective,” self-confessional style. For example, two women who met in school valued their mutual feelings for one another so much that they declared their “same-sex marriage” in a newspaper in 1934.84 In 1941 another woman, Li (莉), recounted her past romantic relationship with a girlfriend, Lin, in an article titled “Sister Lin, Please Forgive Me: Narrating My Homosexual Life.” What prompted Li to compose this article was an anonymous commentary that she came across earlier in the year. Departing from the dominant depictions of homosexuality as unnatural and sick, the published commentary broached the similarities between same-sex and opposite-sex attractions and suggested that people “do not always have to turn their back on homosexual relations.”85 This message moved Li and inspired her to restore the details of her relationship with Lin, who was three years elder. They had met in junior high and became lovers immediately. However, in subsequent years, Li fell in love with new incoming girls and abandoned her relationship with Lin. After writing numerous letters to Li, Lin fell ill one day. At that point, Li was still not sufficiently motivated to pay Lin a visit. When Lin finally passed away, Li gathered a considerable measure of guilt and regret. Her article, in other words, detailed more than just her feelings for Lin. This documented “proof” of a lesbian relationship was also an ad hoc letter asking for forgiveness.

The case studies format that brought these stories to light was consistent with the empirical approach of fin de siècle Western sexology. Among the field’s founding figures, Havelock Ellis, Sigmund Freud, Magnus Hirschfeld, Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1840–1902), Iwan Bloch (1872–1922), and Max Marcuse (1877–1963) all discussed, classified, understood, theorized, and, in essence, imparted knowledge claims about human sexuality by collecting and studying individual life histories. This approach bore little resemblance to the sociological-statistical method adopted later by Alfred Kinsey (1894–1956), the American sexologist who would assume an international reputation by the midcentury.86 As reflected in their correspondences, the Chinese Dr. Sex and his readers faithfully believed that sexuality—hetero or homo—was something to be known scientifically, and that both the experts and non-experts mutually relied on one another for valuable information. The intersubjective dynamic between the Chinese sexperts and their readers mirrored the reciprocal dialogue between medical doctors and their patients in European and American scientia sexualis. As medical historian Harry Oosterhuis has claimed, “the new ways of understanding sexuality emerged out of a confrontation and intertwining of professional medical thinking and patients’ self-definition.”87 Foucault’s observation, again, is germane here: “It is no longer a question of saying what was done—the sexual act—and how it was done; but of reconstructing, in and around the act, the thoughts that recapitulated it, the obsessions that accompanied it, the images, desires, modulations, and quality of the pleasure that animated it. For the first time no doubt, a society has taken upon itself to solicit and hear the imparting of individual pleasures.”88 In his attempt to enlighten the public with reliable and “accurate” knowledge about proper heterosexual behavior, Zhang’s sexological project gave true or false statements of homosexuality an unprecedented scope of comprehensibility in China. It is worth reemphasizing that what scientia sexualis produced was not so much homosexual experience per se than the historical conditions under which it became a conceptual possibility—a system of truth and falsehood that structures identity along the axis of a heterosexual–homosexual polarity.

Competing Authorities of Truth

The public dissemination of scientific knowledge about sexuality was a hallmark of Zhang Jingsheng’s “utopian project,” to borrow the phrase from Leon Rocha.89 In pushing for the public circulation of private sexual histories, Zhang’s sexological enterprise simultaneously defined certain aspects of China’s sexual culture as traditional or modern, whether in terms of modes of narration (literary versus scientific) or knowledge foundations (Daoist alchemy versus Western biology). In this new public of truth, the nature of human desire and passion was openly debated by experts and their readers. But the cast in these debates included other public contenders as well. This section of the chapter highlights another aspect of epistemic modernity crucial to the development of scientia sexualis in Republican China: a public platform on which authorities of truth competed.

Whereas a considerable mass of urban acolytes extolled Zhang by calling him the Dr. Sex, other adepts publicly gainsaid his teaching. These critics ridiculed Zhang’s sexological work mainly for its lack of scientific proficiency. A contributor to the periodical Sex Magazine, Han (瀚), called Zhang’s sexology “fraudulent science [偽科學, weikexue].” In describing the specific type of pleasant odor emitted by women during sexual intercourse, Zhang cited the example of Lin Daiyu, the principle female protagonist of the Qing classic Dream of the Red Chamber. Han criticized this reference on the ground of its historical and factual inaccuracy: “Is Lin Daiyu your relative? Were you physically next to Jia Baoyu [Lin’s lover in the story]? Please do not make such preposterous statements. Speaking from a fact-based perspective, I would like to invite you to collect these pleasant-smelling gases that you describe and subject them to chemical testing.” The author also attacked Zhang for suggesting that male genitals produced yang electrolytic qi and female genitals produced ying electrolytic qi: “to demonstrate that he is deeply familiar with the traditional depiction of yang as masculine and ying as feminine in Chinese culture, [Zhang] inevitably imposed the notions of ying and yang onto the concept of electrolytic qi.” Above all, Han was dismayed by the various kinds of female water that Zhang described. If liquids were indeed released during sexual intercourse, Zhang’s suggestion that electrolytic qi could be produced concomitantly appeared unconvincing. For Han, this only demonstrated that Zhang “does not even understand the most basic principles of electric generation.”90

In the same issue of Sex Magazine, another writer, Qian Qian (倩倩), composed a piece called “Research on the Third Kind of Water.” Targeting the theory of the third kind of water, the article began with a statement that actually attested to the ecumenical significance of Dr. Sex’s work: “Since the publication of Zhang Jingsheng’s Sex Histories, scholarly understandings of sex have multiplied in unexpected ways. At the same time, it has also initiated an increasing number of individuals studying sex and a growing wave of popular fascination with sex research.” However, precisely because Zhang’s theory of the third kind of water had stirred up a revolution of some sorts in popular culture, Qian Qian set out to clarify “what the third kind of water is” for non-experts. In twelve pages, Qian Qian explained in detail three main types of fluids that could be found in female genitalia: menstrual fluid, the secretion of the Bartholin’s gland, and vaginal fluid. “Professor Zhang’s understanding of the third kind of water as the secretion of the Bartholin glands is evidently incorrect,” Qian Qian concluded. “The significant quantity of female discharge during orgasm” that Zhang described “was nothing other than vaginal fluid.” Refuting Zhang, Qian Qian added, “the secretion of vaginal fluid is a continual process, though with growing intensity in intercourse, and does not happen only during orgasm as Professor Zhang understood it.”91

The writings of Dr. Sex drew fire from other more mainstream scholars. Even though Zhou Jianren, author of numerous popular life-science books and an editor at the Shanghai Commercial Press, had praised Zhang’s first two books for their sound philosophical argument, he, too, attacked Zhang’s theory of the third kind of water immediately following the publication of Sex Histories. Zhou argued that Zhang’s theory did not correctly account for the biological process of ovulation in women’s menstrual cycle. Zhou noted that if the female body produces an ovum only on a periodic basis, Zhang’s advice for women to voluntarily release an egg and the “third kind of water” in each sexual intercourse was evidently “pseudo-scientific” at best. Another sex educator, Yang Guanxiong (楊冠雄), even described Zhang as a public figure destructive to the entire sex-education movement. For regular interlocutors in sex education like Zhou and Yang, who kept up with the latest developments in the natural sciences, the most problematic aspect of Zhang Jingsheng’s sexology was its inaccurate grounding in human biology.92 Some writers used the unscientific foundation of Zhang’s writings as a benchmark for distinguishing domestic, second-rate from foreign, “serious and respectable” sex research.93 Other high-profile intellectuals, including Zhou Zuoren, Chen Cunren, Zhang Taiyan (章太炎, 1869–1936), and Hu Shih, weighed in on the debate over the literary value and (in)decency of Sex Histories.94

Out of the many critics of Zhang, the most vociferous was probably Pan Guangdan, the famous Chinese eugenicist who presented himself as a loyal devotee of Havelock Ellis’s sexological oeuvre. Pan described his first impression of Zhang as a “literary freak” (文妖, wenyao) and Zhang’s work as “fake science” (假科學, jiakexue), “fake art” (假藝術, jiayishu), and “not philosophy” (非哲學, feizhexue).95 Pan received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biological science at Dartmouth College in 1924 and Columbia University in 1926, respectively. In light of his high academic performance, Pan was conducted into the Phi Beta Kappa honor society upon his graduation from Dartmouth.96 His educational experience in New York coincided with the peak of the American eugenics movement, the center of which was located in the upper-class resort area of Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island. In 1904 the Station for the Experimental Evolution was established there under the directorship of Charles Davenport with funds from the Carnegie Institution of Washington. In the summer of 1923 and between his undergraduate and graduate studies, Pan visited Davenport’s Eugenics Record Office (founded in 1910) to learn more about human heredity research.

Figure 3.5 Pan Guangdan (1899–1967).

After returning to China in 1926, Pan did not conduct experimental research in biology (given his interest in eugenics, experimentation with human breeding was of course not an option). Instead, like most European and American eugenicists, he spent most of his time studying the ethnosocial implications of sex by constructing extended family pedigrees and collecting other forms of inheritance data.97 His Research on the Pedigrees of Chinese Actors (中國伶人血緣之研究, Zhongguo linren xueyuan zhi yanjiu; 1941) is an example of this.98 Similar to the Anglo-American eugenicists whom he tried to emulate, Pan prioritized the making of an “eugenic-minded” public.99 He did this by delivering numerous lectures around the country and publishing extensively in both academic journals and the popular press to promote his positive vision of eugenics.100 The Chinese public in general viewed him as a trustworthy intellectual in light of his impressive academic credentials. Through Pan, “eugenics” (優生學, youshengxue) quickly became a household term in China in the 1920s and 1930s.101

Sharing the same intellectual worries with Zhou Jianren, Pan depicted Zhang Jingsheng’s writings on human sexuality as “unscientific.” Pan was particularly disdainful of anything Zhang had to say about the relationship between sex and eugenics because he despised Zhang’s lack of formal training in biology. Even though Zhou, like Zhang, had a background in philosophy, his writings on evolution proved his erudition in the modern life sciences. On the contrary, in Pan’s view, Zhang’s ideas about human sexuality demonstrated a fatal failure in communicating the basic principles of human biology. In 1927, Pan responded to Zhang’s theory of female ejaculation:

[Zhang] claims that he has discovered a “third kind of water,” but we do not know what it is. He has indicated that it simply refers to the secretion of the Bartholin glands. If that is the case, then it is really nothing new to any educated person who is familiar with the physiology of sex.… One of the functions of the Bartholin secretions is to decrease resistance during sexual intercourse. The amount of secretion increases as the female partner becomes more aroused, so the quantity of secretion depends entirely on the intensity of her sexual desire and arousal.… Since this function is present in most females, one wonders on what statistical basis does [Zhang] claim that women in our nation usually do not release this third kind of water. When he claims that this kind of water is more typically released in the body of European urban women, one is equally suspicious about the statistical evidence on which he relies, if there is any at all. If he has none yet still speaks so unabashedly in these words, the intention behind making these unsupported claims is dubious.102

Pan attacked Zhang’s understanding of eugenics by citing the statistical data collected by Charles Davenport and Francis Galton. Pan even accused Zhang for having overlooked Galton’s work completely: “Since the Englishman Francis Galton published his Hereditary Genius in 1869, the book has proven to be immensely useful; and the recent developments in intelligent testing have grown exponentially. Why doesn’t [Zhang] consult these works more substantially? He probably is not even aware of the existence of these studies; one really cannot understand why someone would speak about eugenics so elaborately without showing some basic familiarity with this body of scholarship.”103

In his reply, Zhang showed no acquiescence. He pointed out that Pan’s comments “have in fact proven the scientific content of my theory. The third kind of water is, of course, something present in every woman.… I am merely bringing this kind of water to people’s attention and teaching them the ways in which it can be discharged.” Zhang even construed Pan’s recourse to the work of Galton as evidence of poor research and understanding of eugenics: “In terms of heredity and eugenics, [Pan’s] knowledge in these subjects is even more limited. He is familiar with Francis Galton’s work, but Galton’s theory does not seem well-grounded.… Three years ago, I had already indicated in my book, A Way of Life Based on Beauty, that Galton’s eugenic theory is not real science, but what we want is real science.… Please allow me to invite [Pan] to study my work more carefully in addition to Galton’s.”104 To Zhang, Pan was the one who lacked scientific and scholarly integrity. In response to other critics, Zhang emphasized his foreign language ability (which allowed him to distill Galton’s work) as a key credential that set him apart from the numerous “quack” doctors who dismissed Sex Histories.105 In fact, he repeatedly pitched his sexological treatise as marking a pivotal turning point in the larger intellectual endeavor to move away from “pornography” (淫書, yinshu) and toward “scientific sexology” (科學的性學, kexue de xingxue).106

This public correspondence between Pan and Zhang offers a window onto the ways in which, in the 1920s and 1930s, experts defined and debated the boundaries of a scientific discourse of sexuality. An important aspect was the mutual contestation of the credibility and validity of expertise, a regular facet of any scientific discipline. For Pan, formal training in the biological sciences represented a crucial feature of sexological credibility. Even if an expert lacked this credential, sexological competence could still be achieved by acquiring Western scientific knowledge faithfully and refraining from making unsubstantiated empirical claims about sex. This is why he regarded Zhou Jianren as a better equipped sex educator and a more respectable scientist than Zhang Jingsheng. To Zhang, Pan had obviously misinterpreted what he was trying to do. In fact, Pan’s oversight of Zhang’s earlier scholarly output implied a defect in Pan’s research and scholarship. In turn, Zhang even encouraged Pan to study his earlier writings more carefully in addition to the work of foreign scientists like Galton. Since he had already built a foundation of sexological expertise, Dr. Sex believed that this foundation should be consulted, or at least acknowledged, by new incomers to the field, including Pan.

Although Zhang’s theory of female ejaculation formed the most controversial part of his work, his sparse discussion of same-sex sexuality often served as a springboard for rich critique and elaboration. In 1929, for example, Yang Youtian (楊憂天) authored a lengthy essay in Beixin (北新) titled “The Problem of Homosexuality” (同性愛的問題, tongxing’ai de wenti). The opening paragraph squarely framed Yang’s essay as a response to Dr. Sex:

There are many mysteries in the human world, but perhaps sex tops the list like no other topic. In the sexual realm, perhaps the most surprising phenomenon is none other than homosexuality. Dr. Sex, Zhang Jingsheng, left behind [Auguste] Comte’s positivist philosophy, as well as his professorial position at Peking University, in order to explore sexology. This invariably casts him as one odd creature. Yet, Dr. Zhang’s discussion always revolves around male-female sexual relations and is really about nothing more than the different techniques of heterosexual intercourse. In the end, Zhang is still ridiculed by many.…

I do not hold a doctorate in sexology. I am not an education expert, a psychologist, or a medical professional. However, I am keen to raise the issue of homosexuality for public discussion precisely because I want to unravel this mystery and expose its secrecy.107

As Wenqing Kang has noted, although we know very little about the biographical details of Yang Youtian, the significance of this essay can be seen in the debate on homosexuality it generated among sexologists in the late 1920s and early 1930s.108 Specifically, Yang’s essay prompted Hu Qiuyuan (胡秋原), a leftist intellectual and translator of Edward Carpenter’s work, to write a rebuttal, “Research on Homosexuality” (同性愛的研究, tongxing’ai de yanjiu).109 Both essays were collected in a book titled Essays on the Problem of Homosexuality (同性愛問題討論集, Tongxing’ai wenti taolunji) published by the Shanghai-based Beixin shuju (北新書局) in 1930.110

In contrast to Zhang’s scant attention to the topic of homosexuality, Yang’s essay enriched the depth of Chinese sexological understanding in substantial ways. In fact, Yang’s weighty discussion of same-sex sexuality both reflected and foreshadowed the diversification of Chinese sexology in this period. First, Yang extended existing debates on the congenital versus acquired nature of homosexual desire. While most writers simply brought up these two opposing visions of etiological cause, Yang explored their respective genealogies in detail and with impressive nuance. In discussing the intellectual foundations of these two etiological perspectives, he provided rare information on how Western sexologists related these perspectives to the ideas of latent homosexuality, biological and psychosexual hermaphroditism, gender inversion, and bisexuality. This discussion enabled Yang to tap into familiar terrains in the conclusion, focusing on the prevention of homosexuality. Second, while most Chinese sex researchers looked up to British sexologists such as Havelock Ellis, Edward Carpenter, and Marie Stopes as intellectual predecessors, Yang’s balanced coverage drew attention to the significance and contributions of continental European sexological scientists.111 He gave equal weight to the competing theories of homosexuality articulated variously by Carl Westphal (1833–1890), Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Albert Moll (1862–1939), and Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825–1895), among others. This impressed Chinese readers with a more sophisticated spectrum in the historical roots of sexological taxonomy. Third, in presenting a more comprehensive coverage of European sexology, Yang used this opportunity to introduce other categories of sexual perversion, such as sadism, masochism, and fetishism. “Homosexuality is closely connected to these other types of abnormal sexuality,” Yang explained, “so it is quite common to find a homosexual who is inflicted with one or all three of them.”112 Yang’s sexological contribution, although rooted in the often-pejorative language of Western sexual science of the period, thus greatly amplified the scope of sex research in the aftermath of Dr. Sex.