)l

)l / adverb

/ adverbWell, let’s start with the word “practically.”

prac·ti·cal·ly/' praktik( )l

)l / adverb

/ adverb

1. Virtually; almost.

2. In a practical manner.

As a linguist, I love the double entendre of “practically,” and both definitions fit my philosophy perfectly. First, “practically raw” means “almost raw,” representing my belief in substituting non-raw ingredients or using non-raw cooking techniques when desired or warranted. It means that “raw” does not have to be an all-or-nothing affair.

For instance, I will sometimes add a cooked ingredient to an otherwise raw dish, like throwing a handful of black beans into a raw taco filling or including cooked edamame in a raw stir-fry. I also have no problem replacing raw ingredients with non-raw counterparts, such as storebought nondairy milk instead of homemade almond milk or cooked whole grain noodles in place of spiralized zucchini pasta, when it’s convenient and practical for me to do so. Sometimes I even divide up a recipe, making some of it raw and some of it not; for example, I might send most of a batch of kale chips to the dehydrator to dry overnight, but I’ll reserve one serving and bake it for myself right then as an instant-gratification snack.

Practically Raw means that it is okay to sometimes step outside the boundaries of raw, and I even encourage it when it is practical to do so. It means that even if your access to truly raw ingredients or special equipment is limited, you can still utilize what’s available to emulate raw food dishes. I think it’s perfectly fine to use roasted tahini instead of raw in your hummus, for instance, or to bake up flax crackers in the oven instead of dehydrating them.

Practically Raw also applies to time considerations. Let’s say you planned to dehydrate a dish overnight, but you just found out that company’s arriving in two hours; in that case, you may make the practical decision to bake it instead. In all these cases, you’ll end up with an incredibly nutritious meal, and though it may not be all raw or “technically” raw, it’s still a whole foods meal made entirely of natural, unprocessed ingredients.

In short: to be Practically Raw is to be flexible. (This is not, however, the same as being “flexitarian,” a term that refers to someone who has cut down on their meat consumption but still eats animals occasionally.) When I call myself “flexible,” it means I consider all recipes, including (and especially) my own, to be adjustable, adaptable, and amenable to modifications.

When I was in college, I lost some excess weight by employing a low-calorie, low-fat diet and a daily exercise plan. After that, I was officially hooked on health. However, health, insofar as diet is concerned, means something very different to me now than it did back then. My forays into low-cal eating had me avoiding high-fat animal products (like red meat and cheese), of which I’d never been a fan even as a child. During that time, I did consume foods such as skim milk, chicken, and egg substitutes, but I was also introduced to vegetarian meat analogs and soymilk around the same time, so I incorporated those as well. As I acquired more nutrition knowledge, I found myself eating fewer processed foods and less meat and dairy of any kind, eventually to the point where I realized I was only eating chicken once or twice a month at most, and hardly any dairy whatsoever. At that moment, I decided to cut it out for good and start thinking of myself as a vegan.

Within a few months, I was training for my first marathon and feeling slimmer, more fit, and more energetic than ever. I was soon inspired to create a weblog to share my way of eating with the world. I wanted a way to combine my love for writing (my bachelor’s degree is in linguistics) with my passion for nutrition and healthy food. In August 2008, my blog, Almost Vegan (almostveganchef.com), was born.

Why did I call my blog “almost” vegan? The fact is, I eat a vegan diet primarily for health reasons, both physical and mental, and to not contribute to animal suffering, but I’m not a fan of strict or dogmatic “rules” about food. I prefer to be flexible and focus on enjoying what I eat. I think people can sometimes set themselves up for failure if they insist on being “perfect”, and I find I’m psychologically healthier and happier if I don’t “forbid” myself to have any particular type of food. My blog is the embodiment of this philosophy.

Blogging accelerated my journey to maximum health more than anything, even losing weight. I was constantly being introduced to new foods, recipes, and ideas through the vegan blogosphere, and it wasn’t long before raw foodism appeared on my radar. At first, I couldn’t understand why anyone would prohibit themselves from eating a hot meal, or beans, or tofu. Soon, though, it clicked for me: there’s no rule that says you have to eat all raw to be a part of the movement! I realized that raw foodism doesn’t have to be all-or-nothing. I began slowly, trying raw items at a few restaurants and preparing some raw snacks and desserts at home. Everything tasted pretty good, but I still wasn’t convinced that raw food was for me.

My “aha” moment came in 2010, when my then-boyfriend (now husband) Matt and I took a Memorial Day weekend road trip to Dallas, Texas. On our way south from Kansas City, we stopped at a raw restaurant in Oklahoma City called Matthew Kenney OKC (formerly known as 105degrees). I’d heard about it from a fellow blogger, and I was excited to try a 100 percent raw meal for the first time. I never expected to be so blown away by the flavor and quality of the food, or to feel so satisfied and deliriously high on life as I did after that lunch. It was then that I knew that raw food was a path I very much wanted to travel.

In the following months I experimented with raw food and developed a secret dream of attending the Matthew Kenney Academy (formerly called the 105degrees Academy). After a great deal of encouragement from Matt, my family, and my blog readers, I took the plunge: I quit my life insurance job of four years and enrolled at the academy.

Culinary school was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. Within a few months, I was a certified living foods chef and was irreversibly, obsessively in love with raw food and how it made me feel. When I returned home, I set to work increasing the web presence of my name and blog. To that end, in February 2011, I nervously entered an online video contest sponsored by the Living Light Culinary Arts Institute, another raw chef school in California. Imagine my surprise when my video for Caramel-Fudge Brownies (page 204) was elected the winner—by a landslide! In May of that year I took advantage of the cash scholarship prize by enrolling in a 103-hour series of intensive nutrition courses at Living Light, graduating as a certified raw food nutrition educator. Finally, I had some credentials to match my rabid, years-long obsession with health and wellness!

Put simply, a raw vegan diet consists of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds in their natural, unprocessed state, never heated above approximately 118° Fahrenheit (48° Celsius) in order to preserve the full nutritional value (see Cooked vs. Raw on page 12). The benefits of eating raw foods are vast, so whether you’re a committed vegan or a meat-and-potatoes omnivore, here are some compelling reasons to consider adding more raw foods to your daily diet.

Raw food has more of what your body wants and less of what it doesn’t want. A raw vegan diet is rich in vitamins, minerals, fiber, water, essential fatty acids, plant protein, beneficial enzymes and probiotics, phytochemicals, and antioxidants. It is free of processed sugars, artificial sweeteners, chemicals and preservatives, unhealthy fats, animal products, and common allergens that can include gluten and soy. Also, if you buy organic, a raw diet minimizes your intake of pesticides and genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Raw food is gentle on your digestion. Have you ever eaten a large, rich meal, only to feel pangs (literally) of regret shortly thereafter? When you overload your system with heavy cooked food (especially meat, dairy, and processed carbohydrates), digestion becomes a laborious task. When you eat raw, however, not only is digestion speedier and more comfortable, but your body is better able to assimilate the unadulterated nutrients the food contains. The fiber and enzymes in raw food also help ease your body’s digestive process. A raw diet can be particularly helpful to those with food allergies, intolerances, or sensitivities (such as gluten or soy), as raw food is free of most common allergens.

Raw food is kind to animals and to the planet. A vegan diet is one of the most effective ways to fight animal suffering in today’s world. When you shun meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products, you refuse to support the abuse endured by animals raised for food. A raw diet, free of processed foods, also lessens your participation in the environmental destruction perpetrated by today’s industrial agriculture. Such a choice increases the amount of grain available to feed people elsewhere, reduces pollution, saves water and energy, and withdraws your contribution to the clearing of forests for animal farming.

Raw food will send your energy levels through the roof. After an initial detoxification period, when the body is adjusting to a higher intake of pure, nutritious food, most people who transition to a raw diet experience a surge in energy. Don’t be surprised when you feed your body more vibrant, live food and you end up feeling more vibrantly alive! The abundance of vitamins and minerals and the lack of empty calories will combine to make you feel lighter, happier, and more energetic. You may even reap the benefits of improved sleep quality, smoother skin, and a sharper memory.

Raw food can help you achieve and/or maintain your ideal weight. Fresh fruits and vegetables are low in calories but high in vitamins and minerals. The more produce you include in your daily diet, the less room there will be for your old, unhealthy standbys (which were almost certainly higher-calorie). Better yet, you won’t feel deprived, since nuts and seeds contain protein and healthy fats and are extremely filling. Oh, and two words: raw desserts. Yum! Not only will you feel nourished and satisfied, but low-effort weight loss (or maintenance) is more easily attainable.

A great deal of raw food is quick and easy to prepare. No really, it’s true! Yes, you can invest in a dehydrator, but it’s perfectly possible to thrive on a raw diet without one. Think of how long it takes to peel a banana, throw together a salad, blend a smoothie or grab a handful of nuts…then compare that to the time you might currently spend in the kitchen (or waiting for the pizza man!). Often, in the time it would take you to preheat the oven or boil a pot of water, you can easily prepare a filling, satisfying raw meal or snack. A partially raw diet is full of instant gratification.

Raw foods could help you live a longer, healthier life. A raw diet naturally supports the immune system, decreases inflammation, and floods your body with antioxidants, which deactivate free radicals in the body. As a result, eating raw food can help decrease your susceptibility to common ailments like colds, the flu, and fatigue—as well as to more severe and chronic conditions such as cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. In giving your body better nutrition, you’re increasing your own longevity.

You don’t have to eat only raw foods to reap these rewards. Eating raw food is not a black-or-white decision, but rather a matter of proportions. Every raw snack, side dish, or meal you add to your day will benefit your body. Simply put: the more raw foods one eats, the better one feels and the longer one is likely to live.

In short, whether you’re exploring raw food because of an interest in health and longevity, a nagging food allergy or chronic illness, a desire to lose weight, ethical or environmental concerns, or just curiosity, raw food has a lot to offer you. With rewards like these, you may very well find yourself falling head over heels in love with the raw side of life. No matter what your knowledge level or budget may be, raw food can be for you! I’m here to help you ease into a practically raw lifestyle at whatever pace you choose.

“Flexible” is not yet a pervasive buzzword in the raw community, but the seeds of the idea are there, ready to germinate. To start with, most raw foodies have never shied away from making use of certain non-raw ingredients like maple syrup and nutritional yeast. But in just the last couple of years, it’s gone beyond that. Scanning scores of blogs, I’ve observed that many “raw foodists” now admit to including at least some amount of cooked food in their diet. Many members of the community are moving away from a 100 percent raw “ideal” to a more forgiving 80/20-ish mentality. (This is what is meant inside and outside the raw community when they refer to “the 80/20 rule.”) So, while it used to be the case that a person was either Raw or Not Raw, I’ve noticed that people nowadays who are mostly or even halfway raw call themselves “raw foodists.” It isn’t pure, but it works. So, although “practical” and “flexible” are not yet widely used terms in the raw food world, they are terms for which I believe the raw community is ripe and ready. With a practical, flexible outlook on raw food, even people who are brand new to raw will be able to experiment and indulge their curiosity and newfound enthusiasm to any degree they please—which, to me, is the best possible way to give rise to a passion and a lifestyle shift. In addition, those of you who are already devoted raw foodies might find this flexible, practical approach to be a breath of fresh air which you’re ready and eager to inhale.

There is no such thing as “cheating”—only “choosing.” This statement summarizes my entire diet philosophy and is the root of the reason I am “practically raw.” To me, there is a big difference between “I can’t” and “I won’t.” Instead of declaring that I “can’t” have certain foods—a dietary restriction which can invite feelings of deprivation—I prefer to say that I “won’t” eat certain foods, which is a dietary decision that makes me feel comfortable and empowered. Eating practically raw is effortless to me because I don't consider my diet to be a law or commandment that I’m constantly in danger of breaking or “cheating” on—instead, it’s simply a choice I make each day.

It’s well known that raw food isn’t the cheapest of diets. In place of dollar menus and fast-food drive-thrus, a high-raw diet derives its calories from fresh, natural, high-quality, preferably organic fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds that you prepare yourself. Needless to say, this can often cost more—in time and in money—than a diet of processed food. Although you should be prepared to shell out a little more dough up front, keep in mind that you’ll be paying it forward on all the incredible health benefits you’ll soon enjoy.

That said, there are some effective strategies to make raw food more affordable, as well as quicker and easier to prepare. Here is a handy list to refer to whenever you want to strategize the cost and procedures for eating raw food:

Buy in bulk. My favorite way to lower the cost of nuts, seeds, dried fruits, spices, and other shelf-stable items is to buy them in bulk, either at a warehouse store such as Costco, from the bulk bins of a health food store, or from online retailers (see Resources, page 228).

Buy in bulk. My favorite way to lower the cost of nuts, seeds, dried fruits, spices, and other shelf-stable items is to buy them in bulk, either at a warehouse store such as Costco, from the bulk bins of a health food store, or from online retailers (see Resources, page 228).

Or don’t buy in bulk. I know this contradicts the point above, but on the flipside, avoid buying more than you will use. If you’re making a recipe that calls for just 1 rib of celery, for instance, there’s no need to buy a whole bunch; just go to your grocery store’s salad bar for a few cents’ worth of chopped celery. Take advantage of bulk bins in the same way, and only buy as much as you know you’ll use.

Or don’t buy in bulk. I know this contradicts the point above, but on the flipside, avoid buying more than you will use. If you’re making a recipe that calls for just 1 rib of celery, for instance, there’s no need to buy a whole bunch; just go to your grocery store’s salad bar for a few cents’ worth of chopped celery. Take advantage of bulk bins in the same way, and only buy as much as you know you’ll use.

Eat seasonally. Fresh fruits and vegetables that are in season are often cheaper than out-of-season produce flown in from halfway around the world. Search “produce in season” on Google for lists of what’s in season and when.

Eat seasonally. Fresh fruits and vegetables that are in season are often cheaper than out-of-season produce flown in from halfway around the world. Search “produce in season” on Google for lists of what’s in season and when.

Shop sales, farmers markets, and international grocers. Along with shopping seasonally, scope out sales fliers for your local stores, and don’t miss the unbeatable values available at farmers markets, Asian grocers, and other international food stores.

Shop sales, farmers markets, and international grocers. Along with shopping seasonally, scope out sales fliers for your local stores, and don’t miss the unbeatable values available at farmers markets, Asian grocers, and other international food stores.

Plan ahead. Pick out some recipes at the beginning of the week that you’d like to make, then create a schedule for preparing them. Take note of ingredients needed, dehydration times, whether nuts need to be soaked, or if there’s any other component recipes you need to make before you tackle your list.

Plan ahead. Pick out some recipes at the beginning of the week that you’d like to make, then create a schedule for preparing them. Take note of ingredients needed, dehydration times, whether nuts need to be soaked, or if there’s any other component recipes you need to make before you tackle your list.

Prep in advance. A couple of hours of food prep early in the week can save many hours later on. Raw dishes often keep well, too, so you can easily make two to three days’ worth of food (or more) at a time instead of being in the kitchen every single day.

Prep in advance. A couple of hours of food prep early in the week can save many hours later on. Raw dishes often keep well, too, so you can easily make two to three days’ worth of food (or more) at a time instead of being in the kitchen every single day.

Overdo it. You can double or triple the recipes you make so that you have enough for lunch, leftovers, or snacks throughout the week.

Overdo it. You can double or triple the recipes you make so that you have enough for lunch, leftovers, or snacks throughout the week.

Plant a garden. I say this having no green thumb myself, but if you enjoy gardening, try growing some of your own fresh fruits, vegetables, and herbs.

Plant a garden. I say this having no green thumb myself, but if you enjoy gardening, try growing some of your own fresh fruits, vegetables, and herbs.

Sprout. Read up on how to grow your own sprouts—you can find lots of tutorials online. You don’t even need a garden, just a few glass jars and some cheesecloth.

Sprout. Read up on how to grow your own sprouts—you can find lots of tutorials online. You don’t even need a garden, just a few glass jars and some cheesecloth.

Eat raw until dinner. Breakfast is the easiest meal to eat raw. Have a smoothie, a bowl of granola, or some chia porridge, and you’re set! For lunch, I almost always eat leftovers from the night before. A quick-to-make soup or salad is another great lunch option.

Eat raw until dinner. Breakfast is the easiest meal to eat raw. Have a smoothie, a bowl of granola, or some chia porridge, and you’re set! For lunch, I almost always eat leftovers from the night before. A quick-to-make soup or salad is another great lunch option.

Keep it simple. There’s no need for every eating occasion to be gourmet. Fresh fruits and vegetables are nature’s perfect snack, so indulge in those as often as you please.

Keep it simple. There’s no need for every eating occasion to be gourmet. Fresh fruits and vegetables are nature’s perfect snack, so indulge in those as often as you please.

Substitute, substitute, substitute! Anytime an expensive or difficult-to-find ingredient is called for, be sure to consider the substitution suggestions at the end of each recipe, as you may find a thriftier or more readily available alternative. Similarly, if a recipe appears to take more time to prepare than you can spare, watch for tips to speed up prep time by cooking or baking.

Substitute, substitute, substitute! Anytime an expensive or difficult-to-find ingredient is called for, be sure to consider the substitution suggestions at the end of each recipe, as you may find a thriftier or more readily available alternative. Similarly, if a recipe appears to take more time to prepare than you can spare, watch for tips to speed up prep time by cooking or baking.

As I am not a medical or dietary practitioner, the information in this book should not be taken as prescriptive advice. In fact, you should always seek an expert medical opinion before making changes to your diet or supplementation regimen.

However, I credit my passion for nutrition with leading me to embrace veganism and raw foodism. I think it’s incredibly important for everyone to have at least a fundamental grasp on human nutrition; however, many people get lost in the jargon and details of nutritional science. My goal here is to give you a basic primer on nutrition without overwhelming you with technicalities. This is in no way an exhaustive explanation of all things nutrition-related— there’s much more than can be crammed into these few pages—but it’s a great place to start.

Water

Often overlooked, water is one of the most important components of our diet. It makes up 70 percent of our body weight, is found in every one of our cells, tissues, and organs, and is a key actor in almost every bodily function and process. It’s extremely important to stay hydrated every day; eight to ten 8-ounce glasses of pure, filtered water per day is a good minimum to aim for. You can also take in extra fluids through food, and raw food is often a fantastic source. Eating plenty of juicy fruits and water-rich fresh vegetables will help keep your body hydrated and happy.

Calories

A calorie is a unit of energy. One kilocalorie (equivalent to one dietary calorie) is the amount of energy needed to increase the temperature of a kilogram of water by 1°C. That sounds complicated, but nutritionally speaking, calories are simply our body’s preferred form of fuel, used to power everything from breathing to thinking to exercise.

A person’s daily recommended calorie intake depends on a number of factors, including age, sex, height and weight, and activity level. Typically, however, a moderately active woman requires about 2,000 calories per day, with the average man requiring approximately 2,500.

That said, it is usually not necessary to track the exact number of calories you eat. Our bodies are equipped with numerous satiety mechanisms that allow us to intuitively know how much food we require. Sometimes, though, especially after years on a high-calorie, nutrient-poor Standard American Diet, these mechanisms can get thrown out of whack, in which case it can be a good idea to track your calories for a few days and try to recalibrate your body to expect a proper amount of fuel. Dietary calories come from only four sources: proteins, carbohydrates, fats, and alcohol.

Macronutrients

A macronutrient is a chemical compound that provides energy (calories). The preferred source of energy for most of our cells is carbohydrates. After our carb stores are emptied, fat is then utilized. Only after burning up our usable stores of both carbs and fat will the body switch to burning protein (muscle tissue) for energy.

Carbohydrates. Carbohydrates come in numerous forms, but they all contain 4 calories per gram and are derived from plant sources. So-called “simple carbs,” found in fruits and various sugars, require little digestion and thus are a quick energy source, while starchy “complex carbs,” found in vegetables, grains, and legumes, require more digestion time than simple carbohydrates. Because they are burned in a constant, time-released manner, fiber-rich complex carbohydrates are the body’s best source of fuel, as they do not spike blood sugar and can provide sustained physical energy. The bulk of our daily calories—at least 50 percent—ought to come from carbohydrates, emphasizing vegetables and fruits, and limiting added sugars.

Fiber. Though it is a type of carbohydrate, fiber is a non-caloric nutrient, as it passes through our bodies unabsorbed. Fiber is vital to a healthy diet, as it pushes our food through the digestive tract and can also lower cholesterol, decrease the risk of colon cancer, and relieve constipation. You should aim for at least 35 grams daily, but on a raw and vegan diet, I routinely find myself consuming 60-80 grams per day!

Fats. Fats (also called fatty acids or lipids) contain 9 calories per gram and are crucial for energy storage, vitamin and mineral absorption, hormone balance, and cell communication.

Unsaturated fats provide cell membrane fluidity and help transmit nerve impulses. These fats can either be monounsaturated, such as those in olives, olive oil, nuts, and avocados, or polyunsaturated, including the EFAs (essential fatty acids such as omega-3s and -6s) that we must obtain from our diet. Though it’s often thought that fish are the best source of the omega-3 fat DHA, our bodies can actually synthesize it from ALA, an omega-3 fat found in flax, hemp, and chia, as well as in small amounts in leafy greens. If you’re concerned about your body’s ability to convert ALA to DHA, you can take an algae-derived DHA supplement. Omega-6 fats, such as those in seeds and vegetable oils, are essential as well, but they are already quite plentiful in any diet, so it’s not necessary to specifically seek them out.

Every body is different, and due to this biochemical individuality, there is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all diet. Some people like to eat more protein than average, others prefer less fat or fewer carbohydrates, and still others count their daily calories. Some folks want to lose weight; others want to gain. Sometimes there’s a medical issue. For these reasons and more, I wanted to provide the nutritional breakdown for all my recipes.

I’ve also heard complaints about a raw diet being either too low or too high in calories. With this nutritional information, you’ll be able to pick out low- or high-cal recipes as your needs dictate. In addition, you can use the information to combine various dishes into perfectly portioned meals and snacks. For example, after eating a plate of extremely low-calorie, low-fat Spaghetti alla Marinara (page 136) for dinner, you’ll know you can indulge in a highercal dessert like, say, Cinnamon Crumble Coffee Cakes (page 207) afterward, guilt-free.

Medium-chain saturated fats, such as those in coconut products, provide stiffness and stability for cell membranes. (Long-chain saturated fats from animal products, however, can have deleterious effects on our cholesterol and heart health). Man-made trans fats, which are created by hydrogenating vegetable oils (in other words, causing polyunsaturated fats to behave like saturated ones) are unnecessary in our diet and dangerous to our cardiovascular system, and should be avoided. Luckily, they are not found in any natural, raw, vegan foods.

Some people worry that a raw food diet is too high in fat, but bear in mind that the type of fat you’re consuming tends to matter more than the total number of grams. When your diet is filled with anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids, heart-healthy monounsaturated fats, and antimicrobial medium-chain saturated fats, your body will be able to put all of them to beneficial use, unlike the more sinister long-chain saturated and trans fats. (Also see Cutting the Fat, page 18, and Spotlight on Fats, page 187.)

Protein. Containing 4 calories per gram, protein is in every cell in the body. It comprises 20 percent of our body weight and largely makes up our skin, eyes, nails, hair, brain, heart, blood cells, and immune system cells. Proteins in food are actually long chains of amino acids (which are the building blocks of all proteins) that the body breaks down during digestion. Of the twenty naturally occurring amino acids, eight to ten (depending on whom you ask) are deemed “essential” for humans, as they cannot be made within our bodies and must instead be obtained from food.

Most Americans have grossly inflated notions of our protein needs, when in reality the average daily requirements for adults are 46 and 56 grams for women and men, respectively. Not only is this amount easily obtained through a plant-based diet, but there is such a thing as too much protein. An excess of protein in your diet can stress your kidneys, and numerous epidemiological surveys, such as The China Study, have linked high dietary protein intake (particularly of protein from animal sources) with increased risk of cancer. Plant protein is not only healthier, it’s also more bioavailable, meaning that it’s more easily absorbed by our bodies.

Please don’t fret about protein combining or getting “complete proteins” in your diet. Every single food contains a mixture of all the essential amino acids in varying amounts, so as long as you’re eating a varied diet and not living exclusively on apples or macadamia nuts, you’re getting the essential amino acids you need. Beans and legumes, nuts and seeds, grains and pseudograins, and leafy greens are all excellent sources of protein.

Alcohol. If you choose to include alcohol in your diet, it contains 7 calories per gram, but is not an essential nutrient. I myself enjoy the occasional glass of wine or mixed drink; just be sure not to overdo it, and always drink safely and responsibly.

Micronutrients are nutrients we require in small quantities to orchestrate many of our bodies’ physiological functions.

Vitamins. Vitamins are organic compounds that must be obtained through our diet. They are classified as either fat-soluble (vitamins A, D, E, and K) or water-soluble (all eight B vitamins and vitamin C). Vitamins have diverse functions in the body, including regulation of metabolism and cell and tissue growth. Some vitamins, such as vitamin C, also function as antioxidants. The hardy fat-soluble vitamins are absorbed with the help of lipids (fats) and can be stored in our bodies over time, whereas the more fragile water-soluble vitamins are susceptible to heat damage, and since they dissolve easily in water in our bodies, they are not readily stored.

Vitamins occur in abundance in raw food, especially fresh fruits and vegetables, with the exception of vitamin D (which is best obtained through sunlight) and vitamin B12 (which must be supplemented in vegan diets). Some folks think that the absence of B12 indicates that a vegan diet is an unsuitable eating style for modern humans, who usually get their B12 from animal products. It may surprise you to learn that factory-farmed meat contains B12 because the animals are given supplements! Take a shortcut by ingesting a B12 supplement yourself.

Minerals. Minerals are elements, so they are derived from the earth and do not break down into smaller compounds. They are important for our nervous system, skeletal system, energy production, and much more. Sodium, calcium, iron, potassium, magnesium, zinc, and selenium are a few of the minerals that must be obtained from our diet. Though most people think of dairy as the best source for calcium, in reality, leafy greens are the calcium kings! Iron, also, is found in more than just animal products—nuts, seeds, and leafy greens all contain it, for instance. Also, plant-based (non-heme) iron is selectively absorbed by our bodies (unlike heme iron found in meat), ensuring that we never store an excess, which can lead to iron toxicity.

Antioxidants. Antioxidants reduce levels of oxidative stress in our bodies by donating an electron to neutralize free radical molecules, which wreak havoc on our cells. Potent antioxidants include vitamin C, vitamin E, resveratrol, lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin, flavonoids, carotenoids, and many more, each with their own unique set of functions. Many antioxidants are heat-sensitive, so they’re best obtained from raw foods. Some people will claim that certain antioxidants, like lycopene in tomatoes, are more bioavailable when cooked, but this is not the case—cooked foods simply contain less water, and therefore more lycopene per gram, than their raw forms. Therefore, it’s a matter of concentration, not quality or availability.

As mentioned, this is but a cursory glance at the science of nutrition. There is much more to be said about these topics as well as others, such as phytonutrients, polyphenols, probiotics, plant sterols, and so many more! I highly encourage you to use this information as a springboard to your own investigations into the wonderful world of nutrition.

I hope the information provided here has convinced you that a vegan diet is not only nutritionally adequate, but is also one of the simplest and healthiest ways to eat a wide variety of nutrients every day. But why is raw vegan food nutritionally superior to cooked vegan food?

Nutrient loss: Water-soluble vitamins, including vitamin C and all B-complex vitamins, and most antioxidants are susceptible to heat damage and are often lost through the processes of cooking, boiling, grilling, frying, and pasteurization. Think about it: we humans can’t survive for very long in an environment that is 118°F or hotter. Similarly, many nutrients can’t withstand that much heat, either.

Nutrient loss: Water-soluble vitamins, including vitamin C and all B-complex vitamins, and most antioxidants are susceptible to heat damage and are often lost through the processes of cooking, boiling, grilling, frying, and pasteurization. Think about it: we humans can’t survive for very long in an environment that is 118°F or hotter. Similarly, many nutrients can’t withstand that much heat, either.

Toxins: Harmful carcinogens and toxins such as advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs), acrylamide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), heterocyclic amines, and nitrosamines are produced when certain foods are cooked, especially at high temperatures. These compounds have been linked to a variety of ailments, from cancer to DNA damage. Though you can often avoid most of these by shunning animal products, carb-rich plant foods cooked with high heat can also form some of these dangerous substances.

Toxins: Harmful carcinogens and toxins such as advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs), acrylamide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), heterocyclic amines, and nitrosamines are produced when certain foods are cooked, especially at high temperatures. These compounds have been linked to a variety of ailments, from cancer to DNA damage. Though you can often avoid most of these by shunning animal products, carb-rich plant foods cooked with high heat can also form some of these dangerous substances.

Fat rancidity: Certain fats, especially delicate polyunsaturated fats (including essential fatty acids like omega-3s and -6s), are extremely sensitive to heat and can turn into trans fats when cooked. As often as possible, eat your fats in their raw forms to avoid the carcinogenic qualities of heated, rancid fats and oils.

Fat rancidity: Certain fats, especially delicate polyunsaturated fats (including essential fatty acids like omega-3s and -6s), are extremely sensitive to heat and can turn into trans fats when cooked. As often as possible, eat your fats in their raw forms to avoid the carcinogenic qualities of heated, rancid fats and oils.

Enzymes: Our bodies produce our own digestive and systemic enzymes, but food contains enzymes too. Food enzymes, which are destroyed by cooking, aid our own digestive enzymes in breaking down nutrients in the stomach. The “enzyme theory” of raw food nutrition is often dismissed, since food enzymes are destroyed anyway once they reach the hydrochloric acid in our stomach, but the fact is that before descending to the acidic lower stomach, the food we eat remains suspended in our upper stomach for about 30 minutes, during which time live food enzymes can indeed aid in nutrient breakdown.

Enzymes: Our bodies produce our own digestive and systemic enzymes, but food contains enzymes too. Food enzymes, which are destroyed by cooking, aid our own digestive enzymes in breaking down nutrients in the stomach. The “enzyme theory” of raw food nutrition is often dismissed, since food enzymes are destroyed anyway once they reach the hydrochloric acid in our stomach, but the fact is that before descending to the acidic lower stomach, the food we eat remains suspended in our upper stomach for about 30 minutes, during which time live food enzymes can indeed aid in nutrient breakdown.

Allergies and intolerances: Raw food is naturally free of most common allergens, such as gluten, wheat, soy, eggs, milk, fish, shellfish, and peanuts. The notable exception to this is tree nuts; raw food has loads of those! As long as you’re not nut-sensitive, a high-raw diet can free you from worry regarding most common food allergies and intolerances and the gastrointestinal distress they can cause.

Allergies and intolerances: Raw food is naturally free of most common allergens, such as gluten, wheat, soy, eggs, milk, fish, shellfish, and peanuts. The notable exception to this is tree nuts; raw food has loads of those! As long as you’re not nut-sensitive, a high-raw diet can free you from worry regarding most common food allergies and intolerances and the gastrointestinal distress they can cause.

Elimination of processed foods: Although a cooked vegan diet often cuts down one’s intake of processed food products, many vegans do still consume an abundance of faux meats and cheeses, white flours and sugars, and over-processed snack foods. Processed food can virtually disappear from your diet if you adopt a high-raw lifestyle.

Elimination of processed foods: Although a cooked vegan diet often cuts down one’s intake of processed food products, many vegans do still consume an abundance of faux meats and cheeses, white flours and sugars, and over-processed snack foods. Processed food can virtually disappear from your diet if you adopt a high-raw lifestyle.

Alkalinity/acidity: Cooking a food tends to turn its pH more acidic, and while there’s a complex scientific explanation behind it, suffice it to say our bodies prefer alkaline-forming foods. The less acidic your diet is, the better your body handles tasks like smoothing digestion and soothing inflammation.

Alkalinity/acidity: Cooking a food tends to turn its pH more acidic, and while there’s a complex scientific explanation behind it, suffice it to say our bodies prefer alkaline-forming foods. The less acidic your diet is, the better your body handles tasks like smoothing digestion and soothing inflammation.

None of this information is meant to scare you into never eating cooked food again. In fact, I don’t advocate that at all! Instead, take all of this as evidence that including a variety of raw fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds in your daily diet is an excellent way to up your micronutrient intake and absorption and minimize your exposure to allergens and toxins.

Organic food tends to be more expensive than conventionally grown food, but the truth is that it’s worth the price. Organic produce and other ingredients are grown without the use of pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, genetically modified organisms (GMOs), or ionizing radiation (all potential dangers to our health). Organic farmers tend to emphasize the use of renewable resources and the conservation of soil and water to enhance environmental quality for future generations. On top of all that, organic produce has been found to have higher concentrations of vitamins, minerals, and disease-fighting antioxidants and phytochemicals than conventionally grown produce. And if you ask me, it simply tastes better!

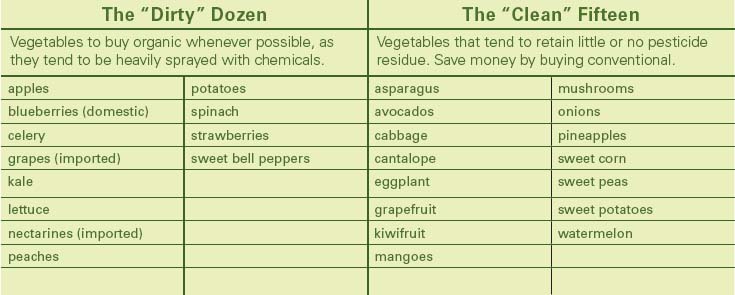

Since organic farming is typically more labor-and cost-intensive, and is not subsidized by the U.S. government, we as consumers must pay a little extra for our organic food. Certain crops are more heavily sprayed with pesticides than others, and are thus more important to buy organic (the “dirty” dozen). On the other hand, another group of vegetables (the “clean” fifteen) retain little to no pesticide residue, so you can feel comfortable saving some dollars there by buying conventional. (See the table on page 14.)

The produce you find at farmers markets may or may not be organic regardless of whether the farm has USDA organic certification; simply ask the farmer about their growing methods or use of pesticides before buying.

Here’s a basic run-through of products and ingredients that a raw vegan diet puts to use. I’ve categorized them in the way that makes the most sense to me, though certain items may belong in multiple categories. For notes on where to find specific products, be sure to check out the Resources section (page 228).

It’s essential to have a variety of fresh fruit in your house at all times. Fruit makes the perfect snack, and it’s the crucial ingredient in most smoothies. Some of my favorites are apples, bananas, berries (strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, blackberries), cherries, grapes, kiwis, mangos, melons (watermelon, honeydew, cantaloupe), peaches, pears, and pineapples. Citrus fruits like limes and (especially) lemons are also great things to have on hand, since their juice is frequently used as an acid in recipes. Only a couple of my recipes include orange juice or oranges, as I’m not a huge fan of the flavor, but I know many people love them!

Good fresh fruit can’t be found year-round in many locales, so I keep my freezer stocked with bags of organic frozen fruit, especially in winter. It’s particularly convenient for smoothies, since you can throw the frozen fruit right into the blender or food processor.

Dried fruits are also an important staple, especially dates, which are very often used as a sweetener in raw food. Raisins (the dark kind as well as golden raisins), dried cranberries, and dried figs are also great to have.

Fresh vegetables comprise perhaps the greatest portion of a raw food diet. Some common and delicious veggies include asparagus, broccoli, carrots, cauliflower, celery, corn, mushrooms, onions, peas, and squash (butternut, yellow squash, zucchini). Don’t forget about fresh garlic and ginger, which make amazing additions to so many savory recipes. Although avocados, cucumbers, peppers (including bell peppers), and tomatoes are botanically counted among fruits, they are more often considered vegetables in the culinary sense, so i’ve categorized them here as such. Leafy greens are an important category to include in your diet on a daily basis. The most common are lettuces (such as romaine), cabbage, spinach, and kale, but don’t forget about others, such as collard greens, Swiss chard, bok choy, endive, radicchio, arugula, watercress, and more.

Veggies (and fruit, for that matter) tend to be cheaper when they’re in season, so I rotate my intake of produce year-round. I’m not big on frozen veggies, with the exception of frozen corn (which is actually a grain rather than a vegetable) and frozen peas, but a couple bags of organic frozen mixed veggies are not a bad thing to have on hand.

Dry-packed sundried tomatoes (technically a fruit) are also often used in raw food, as are common sprouts such as alfalfa or sunflower sprouts.

Nuts are a jack-of-all-trades in raw food. They can be chopped, crushed, blended, or eaten whole; they can add texture, flavor, crunch, or creaminess to a dish. Almonds, cashews, macadamia nuts, pecans, and walnuts are the ones I consider essential, and Brazil nuts, hazelnuts, pistachios, and pine nuts are others I like to stock up on. Whenever possible, buy organic raw nuts rather than roasted and/or salted varieties; however, in a pinch, you can use roasted, unsalted varieties. Store raw nuts in your fridge or freezer so their delicate fats don’t go rancid. Or, if you want to make your raw nuts shelf-stable, just soak them (referencing the soaking table on page 21) and then dehydrate them for 12 to 24 hours (or bake at 200°F for about 2 hours), until crisp. That way, they’ll stay fresh much longer at room temperature.

Nut butters are also a key ingredient in many raw dishes, not to mention one of my favorite snacks ever! I like to keep a jar each of raw almond butter, coconut butter, and cashew butter on hand. Organic raw nut butters can be pricey, so you can use non-raw varieties if you choose. Once opened, store nut butters in the fridge.

Coconuts, though technically a “drupe,” not a nut, are another vital ingredient in raw cuisine. Fresh young Thai coconuts are prized for their sweet, electrolyte-rich water and their creamy inner flesh, or “meat.” I recommend buying young coconuts at an Asian supermarket, where they are much cheaper. If you’re new to fresh coconuts, Google “how to open a young coconut + video” for tutorials on how to open one—it’s easy, I swear! In my recipes, I frequently call for a mixture of coconut butter + filtered water to replace young coconut meat if need be, though there’s nothing quite like the fresh. If you prefer, you can buy coconut water in aseptic containers. Unsweetened shredded coconut is also handy for many dessert recipes, as well as to make homemade Coconut Butter (recipe on page 92).

Food safety laws in the United States mandate that all raw almonds be pasteurized before sale. This means that even though your almonds may be labeled “raw,” chances are they’re not. As frustrating as this can be, let’s keep it in perspective—it’s not the end of the world. When it’s all I have access to, I make do with pasteurized almonds. If you can afford it, though, seek out truly raw Italian almonds online (see Resources, page 228) or buy direct from a grower.

For a very different reason, cashews are also not truly raw. The inside of a cashew shell is coated with a resin that is toxic to humans, so the only safe method to open them is by steaming. Nonetheless, cashews play an important role in many raw food recipes, so don’t kick them out of your pantry! You can find supposedly “hand-cracked” cashews online for a pretty penny, but whether or not they’re truly raw is up for debate.

Just as with nuts, seeds are a very versatile ingredient. Flaxseeds, both whole and ground, are often used in the preparation of raw food. They act as a thickener, binder, or crunch-factor. You can make your own flax meal by grinding whole golden flaxseeds in a coffee grinder, but you can also buy pre-ground flaxseed. Chia seeds have a similar gelling effect, but are more shelf-stable. Hempseeds can be costly, but they’re so worth it! Sunflower seeds, sesame seeds, and pumpkin seeds (or pepitas) are also oft-used. Sesame seed butter, a.k.a. tahini, is a key ingredient in many recipes. Raw tahini can be expensive and tough to find, so you can always substitute roasted tahini in my recipes. Store all seeds and seed butters in your fridge.

Unrefined, virgin coconut oil and a high-quality, cold-pressed extra-virgin olive oil are the two most important oils to have in your pantry. A small bottle of sesame oil is nice to have, though I recommend toasted sesame oil instead of raw, as it’s far more flavorful. You can also buy nut and seed oils such as flaxseed, hempseed, almond, or macadamia nut, but they must be refrigerated as they are subject to rancidity. I don’t use those oils often, though, as I prefer to just eat the whole nut or seed!

Almond flour, whether storebought or made at home by drying the leftover pulp from making almond milk, is the flour I use most often in raw recipes. Oat flour and/or buckwheat flour (again, either storebought or made from soaked/dehydrated/ground buckwheat or oat groats) are used frequently as well, often in conjunction with heavier nut flours. Coconut flour absorbs a great deal of water and creates the most tender raw desserts you’ll ever eat. Cashew flour makes an appearance now and then, and can easily be made by pulsing raw cashews to a powder in a food processor. (For more details on making your own raw flours, see page 21.) A raw diet typically eschews most grains, but oat groats, pseudograins like quinoa and buckwheat, and wild rice are great for soaking and sprouting. I like to keep raw oat flakes (or simply old-fashioned rolled oats) on hand, too. For all oat products, remember to buy certified gluten-free brands if you’re sensitive to the traces of gluten sometimes present on oats.

Raw agave nectar is the most common all-purpose sweetener used in raw cuisine, despite some recent bad press. When purchasing raw agave, make sure you buy a trusted brand that doesn’t cut their product with high-fructose corn syrup. My favorite agave substitute is raw coconut nectar, which is slightly thicker and a touch less sweet, but is a less-processed alternative. (I actually use coconut nectar far more often than agave, but I don’t call for it in my recipes primarily because it’s more expensive and harder to find.)

Pure maple syrup, though not raw, lends a distinctive flavor to raw recipes and pairs wonderfully with chocolate or cinnamon. Dried dates, especially the Medjool variety, are a fantastic whole-food sweetener. For a powdered sweetener, coconut palm sugar is a low-glycemic granulated sweetener that tastes very much like brown sugar. The best calorie-free sugar substitute is all-natural stevia leaf extract, which can be found in liquid or powdered forms.

There are a plethora of other unrefined sugars out there to check out (some raw and some not); you might explore other options like lucuma powder, yacon syrup, brown rice syrup, Sucanat, molasses, date syrup, date sugar, maple sugar, or evaporated cane juice. (Learn more about agave, stevia, and date syrup in Desserts, pages 196-197.)

Chocolate is a superfood, people! There’s nothing like a homemade raw chocolate confection to remind you of the wonders of raw food, so stock your pantry with raw cacao powder (or, alternatively, use carob powder or regular unsweetened cocoa powder), cacao butter, and cacao nibs. Other completely optional superfoods you might keep around are exotic dried fruits like gojiberries, mulberries, and goldenberries; raw protein powders made of hemp and sprouted brown rice; and other nutritious superfood powders like maca, mesquite, spirulina, wheatgrass, or other powdered greens. A bottle of dairy-free probiotic powder, the “good bacteria” that allow you to create tangy, healthful raw yogurts and cheeses (see Resources, page 228, for where to buy), is worth having, and lasts a long time in the refrigerator.

A number of flavoring agents play important roles in raw cuisine. Keep a fully stocked cabinet of dried herbs and spices so you always have a variety of flavor options on hand. Fresh herbs, such as flat-leaf parsley, cilantro, and mint, can really elevate the flavor of a dish. A good-quality sea salt is also essential—don’t use the awful bleached, iodized stuff if you can avoid it! Tamari or another soy sauce (like nama shoyu or liquid aminos) comes in very handy, as do vinegars like apple cider, rice, and balsamic. There are many types of miso paste available; I prefer mild white miso, but if you’re avoiding soy, seek out chickpea or barley miso. Flavor extracts—at the very least, a good vanilla extract—belong in your kitchen as well. Last but not least, nutritional yeast lends a cheesy, savory taste and a dash of B vitamins to anything you include it in.

Jarred or bottled olives (I like Kalamata), capers, and chipotle chiles offer big flavor in little packages. I’m not big on sea vegetables generally, but I do keep nori sheets and dulse flakes on hand, and of course kelp noodles, which will keep for months in the fridge. I’m also a fan of Irish moss, a seaweed which can be soaked and blended with water to create a gelatin-like paste, perfect for adding fluffiness to raw “baked” goods. (See page 23 for details on how to make Irish moss gel.)

Fermented foods like kimchi and sauerkraut are popular with raw foodists; you can make your own or buy them. Lecithin, either soy (not raw) or sunflower (raw), will make any blended or puréed item, like nut milks, extra-creamy. If you like sprouts, buy dry beans, lentils, and seeds like alfalfa to grow your own sprouts.

You may choose to include coffee (especially cold-pressed) and tea (especially sun-brewed) in your diet as well. I think certain convenience foods, like good-quality storebought nondairy milks, bottled lemon juice, and nondairy chocolate chips have a place in even a raw food pantry for those “emergency” times when you might need them.

Even though the dietary fats found in raw food are nutritious and health-promoting, some folks may have reasons (such as medical) to reduce their intake of fats from all sources. You can’t eliminate too much fat from the recipes in this book, lest the taste or texture suffer, but for those who wish to cut the fat a little bit, I do have some tricks up my sleeve. (Also see Spotlight on Fats, page 187.)

Reducing oil: Anytime a recipe calls for a 1/4 cup or less oil, you can usually get away with reducing it by up to half. If more than 1/4 cup is called for, I’d recommend eliminating no more than 25 percent of the oil.

Reducing oil: Anytime a recipe calls for a 1/4 cup or less oil, you can usually get away with reducing it by up to half. If more than 1/4 cup is called for, I’d recommend eliminating no more than 25 percent of the oil.

Oats for nuts: In recipes that make use of ground (but not blended) nuts—such as brownies and blondies, pie and tart crusts, cookies and cakes, energy bars, or even savory seasoned nut meats—you can replace up to one quarter of the nuts in the recipe with an equal amount of raw rolled oat flakes or old-fashioned rolled oats. Be sure to pulse the oats in with the nuts so they’re coarsely ground and well-incorporated.

Oats for nuts: In recipes that make use of ground (but not blended) nuts—such as brownies and blondies, pie and tart crusts, cookies and cakes, energy bars, or even savory seasoned nut meats—you can replace up to one quarter of the nuts in the recipe with an equal amount of raw rolled oat flakes or old-fashioned rolled oats. Be sure to pulse the oats in with the nuts so they’re coarsely ground and well-incorporated.

More greens, less dressing: When making any of the kale chip or salad recipes, increase the amount of greens called for without increasing the quantity of dressing or coating. For example, try using 1 1/2 bunches of kale for a batch of chips instead of just one bunch; you’ll get more servings out of the batch, and as a result, each serving will be lower in fat and calories.

More greens, less dressing: When making any of the kale chip or salad recipes, increase the amount of greens called for without increasing the quantity of dressing or coating. For example, try using 1 1/2 bunches of kale for a batch of chips instead of just one bunch; you’ll get more servings out of the batch, and as a result, each serving will be lower in fat and calories.

Replacing blended cashews: You can achieve a similar affect with less fat by using Irish moss. It’s a type of seaweed, which, when soaked and blended with water, creates a gelatin-like paste. If you can find it, snatch it up! (It’s widely available online, but prices tend to be steep. I find mine very cheap at an Asian superstore; it’s labeled rong bien in Vietnamese.) Follow the instructions on page 23 to turn the raw Irish moss into a thick gel. Anytime a liberal amount of nuts (at least 3/4 cup, usually cashews) is completely blended into a recipe—particularly in soups, creamy sauces, nut-based hummus, puddings, pie and tart fillings, and ice cream—you can safely replace up to one quarter (or even one third, if you’re daring like that) of the cashews with an equal amount of Irish moss gel without adversely affecting the flavor.

Replacing blended cashews: You can achieve a similar affect with less fat by using Irish moss. It’s a type of seaweed, which, when soaked and blended with water, creates a gelatin-like paste. If you can find it, snatch it up! (It’s widely available online, but prices tend to be steep. I find mine very cheap at an Asian superstore; it’s labeled rong bien in Vietnamese.) Follow the instructions on page 23 to turn the raw Irish moss into a thick gel. Anytime a liberal amount of nuts (at least 3/4 cup, usually cashews) is completely blended into a recipe—particularly in soups, creamy sauces, nut-based hummus, puddings, pie and tart fillings, and ice cream—you can safely replace up to one quarter (or even one third, if you’re daring like that) of the cashews with an equal amount of Irish moss gel without adversely affecting the flavor.

Bulking up breads: Irish moss gel has another excellent use: adding volume and an appealing fluffy quality to raw breads. Many of the bread recipes benefit texturally from the addition of Irish moss gel (I’ve noted each one with a Variation option). As an added bonus, thanks to the extra volume, you’ll get more servings from the batch, with each serving being a touch lower in fat.

Bulking up breads: Irish moss gel has another excellent use: adding volume and an appealing fluffy quality to raw breads. Many of the bread recipes benefit texturally from the addition of Irish moss gel (I’ve noted each one with a Variation option). As an added bonus, thanks to the extra volume, you’ll get more servings from the batch, with each serving being a touch lower in fat.

Stretching smoothies: Once you’ve mastered the art of Irish moss gel, you might wind up looking for ways to use up the last of a batch. Smoothies are a great way: add about 1/4 cup gel (or even more, if you’re not sensitive to the taste) plus an equal amount of filtered water to any smoothie recipe to stretch the number of portions, which will reduce the calories and fat grams per serving.

Stretching smoothies: Once you’ve mastered the art of Irish moss gel, you might wind up looking for ways to use up the last of a batch. Smoothies are a great way: add about 1/4 cup gel (or even more, if you’re not sensitive to the taste) plus an equal amount of filtered water to any smoothie recipe to stretch the number of portions, which will reduce the calories and fat grams per serving.

A kitchen full of expensive gadgets is not required to make delicious raw food. Although pricey appliances like dehydrators and high-speed blenders are very useful for churning out gourmet, 100 percent raw delicacies, it’s really very easy to get by with just a minimum of equipment. Here’s what I use most often in my own kitchen, as well as some alternatives to the more obscure or costly equipment.

Good knives. This one is non-negotiable. At the very least, you should have one sharp, high-quality chef’s knife (seven to eight inches in length) and one paring knife (about three inches in length). If you’ll be cracking fresh coconuts, you’ll also need a heavy cleaver.

Cutting board. Wood, bamboo, plastic, or any other kind you choose—you need a stable (and washable) surface on which to chop your ingredients.

Mandoline. A mandoline will allow you to slice a whole pile of vegetables or fruit paper-thin in record time, but you can always, of course, just do it by hand.

Spiralizer. This optional, inexpensive gadget makes spaghetti-like strands out of zucchini and other vegetables. In lieu of a spiralizer, you can very thinly slice the zucchini lengthwise with a vegetable peeler or mandoline, then carefully cut those slices into fettuccine-shaped pieces. It’s quite a bit more work to do it that way, but it gets the job done.

Measuring spoons and cups. You must have a set of measuring spoons as well as both liquid and dry measuring cups.

Mixing bowls, storage containers, and jars. You’ll need plenty of vessels in which to make and store your homemade raw goodies, so have a variety of sizes of mixing bowls, storage containers (plastic or, preferably, glass), and Mason jars on hand.

Pans. You can get by with just a baking sheet or two, an 8-or 9-inch square pan, and a 9-inch pie plate, but I’d also recommend a 9-inch tart pan (and/or mini tartlet pans), and a small (6-or 7-inch) springform pan.

Utensils. A vegetable peeler, whisk, sturdy rubber spatula, wooden spoon, box grater, and small strainer are all must-haves. An offset spatula, Microplane grater (for zesting), ring molds, and kitchen scissors are also nice to have.

Strainer/colander. A strainer or colander is good for rinsing off fresh produce or soaked nuts and seeds. If you plan to make nut cheeses like the ones in the chapter Cheeses, Spreads, & Sauces, buy some inexpensive cheesecloth to line your strainer.

Nut milk bag. Crucial for making smooth, homemade nondairy milks, a nylon nut milk bag (or sprouting bag, or paint straining bag) is used to separate the pulp from the milk. See Reources (page 228) for where to get one, and Basic Techniques (page 21) for instructions on how to use one.

Squeeze bottles. You’d be shocked just how useful a couple of inexpensive plastic squeeze bottles can be in your kitchen! You can use them for drizzling sauces, storing condiments, and much more. That said, you can certainly get by without them.

Coffee/spice grinder. A coffee grinder or spice grinder is wonderful for making fresh flax meal and spice powders, but it isn’t a necessity.

Food processor. A food processor is essential for a good deal of raw food preparation. You may be able to get around it sometimes by chopping ingredients by hand, but more often than not, a food processor is indispensable. It doesn’t have to be fancy—you can easily find a good one for under $100—and all you need is the standard S-blade that comes with it. I have both an 11-cup model and a 3-cup mini version, but all you really need is the larger, standard size.

Ice cream maker. Another optional item, ice cream makers are a fun and easy way to churn up raw vegan frozen treats. However, I would never deem it a kitchen necessity.

High-speed blender. Just a few years ago, I would’ve found the idea of a $600 blender ludicrous. Now, I wouldn’t give mine up for anything! A super-powerful blender such as a Vitamix or Blendtec will transform the way you look at smoothies, soups, sauces, and much more. It’s definitely an investment, but it’ll last a lifetime, and you won’t believe the dreamily smooth purées it’ll turn out.

I realize, however, that a $400 to $600 appliance is not within many people’s budget, so don’t fret if all you have is a more modest blender. Your purées may be slightly less smooth, but it’ll still do the trick. When blending nuts and seeds, you may just want to soak them an extra couple hours if using a regular blender.

Dehydrator. Dehydration is the process of evaporating liquid out of foods. In raw cuisine, a dehydrator is used to “bake” foods at temperatures below 118°F (48°C) in order to preserve all the nutrients, vitamins, and enzymes within. Dehydrators are incredibly versatile—you can make just-moist-enough cakes, shatteringly crisp crackers, perfectly chewy burgers or cookies, and much more, all without damaging a single nutrient. Excalibur, TSM, and Sedona are all top-quality brands. For each dehydrator tray, you’ll also need a Teflex sheet, a nonstick surface to place wet foods on until they’re dry enough to transfer to mesh trays. Any time a recipe directs you to dehydrate, set the temperature of your machine anywhere between 105°F and 115°F (40 to 46°C).

Not everyone wants to invest in a dehydrator, at least not right away, so for those just getting started in raw food, I’ve provided conventional oven-baking directions for almost every recipe in this book. While it’s true that if you use a regular oven, your food won’t be technically raw (i.e., it will be cooked above 118°F), your finished product will still be composed of all-natural, ultra-healthful fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds. In fact, you may enjoy the results so much that you decide you want to add a dehydrator to your kitchen.

Alternatively, you can mimic dehydration by using your oven on its lowest (“warm”) setting and leaving the door cracked, although this method does waste a lot of energy.

Other appliances, such as juicers, stand mixers, and immersion blenders, can also be great additions to any kitchen, but aren’t required for any of the recipes in this book.

In raw food prep, nuts and seeds are soaked for multiple reasons. Some, particularly nuts with skins such as almonds, walnuts, and pecans, contain enzyme inhibitors that must be neutralized through soaking so that our bodies can more comfortably digest them. Other times, nuts and seeds are soaked for texture’s sake, to allow them to soften and become easier to blend. When a recipe calls for “1 cup nuts, soaked,” simply place one cup of dry nuts in a bowl, cover with cold filtered water, and let sit at room temperature for the amount of time indicated in the table below. In a recipe where the nuts or seeds require soaking, the amount called for is always measured dry, before the soaking step. The soaking time need not be precise; if you only have 30 minutes to soak some cashews, for instance, just use warm water instead of cold, and place the bowl in a warm dehydrator to speed the soaking process.

You may also choose to soak and dehydrate all your nuts to extend their shelf life. In that case, soak the nuts for the proper amount of time, then transfer to mesh-lined dehydrator trays and dehydrate for 24 to 48 hours (or bake at 200°F for about 2 hours), until crisp.

When a recipe calls for “1 cup dry nuts,” do not soak before preparing the recipe.

Hold a nut milk bag open over a large bowl or pitcher and simply pour your freshly-blended nut milks into the bag. Twist, squeeze, and knead the bag (with clean hands!) to extract all the milk (taking care not to spill it outside the bowl) from the pulp, which can then be dehydrated or baked to make flour.

Almond Flour. To make almond flour, strain freshly made Almond Milk (page 30) through a nut milk bag, reserving the pulp. Transfer the pulp to a Teflex-lined dehydrator tray and dehydrate for 8 to 12 hours or overnight, until dry. Alternatively, transfer the pulp to a parchment paper-lined baking sheet and bake at 200°F for 1 to 2 hours, or until dry. Crumble and store in the refrigerator or freezer.

Almond Flour. To make almond flour, strain freshly made Almond Milk (page 30) through a nut milk bag, reserving the pulp. Transfer the pulp to a Teflex-lined dehydrator tray and dehydrate for 8 to 12 hours or overnight, until dry. Alternatively, transfer the pulp to a parchment paper-lined baking sheet and bake at 200°F for 1 to 2 hours, or until dry. Crumble and store in the refrigerator or freezer.

Oat Flour. To make oat flour, soak whole raw oat groats in cold filtered water for 8 to 12 hours or overnight. After rinsing and draining, transfer the oats to a mesh-lined dehydrator tray and dehydrate for 24 hours, or until dry. Alternatively, transfer the oats to a parchment paper-lined baking sheet and bake at 200°F for 2 to 4 hours, or until dry. Transfer the dried oats to a high-speed blender or food processor and process into a flour-like consistency. Sift the flour to remove any large, hard crumbs. Store in the refrigerator.

Oat Flour. To make oat flour, soak whole raw oat groats in cold filtered water for 8 to 12 hours or overnight. After rinsing and draining, transfer the oats to a mesh-lined dehydrator tray and dehydrate for 24 hours, or until dry. Alternatively, transfer the oats to a parchment paper-lined baking sheet and bake at 200°F for 2 to 4 hours, or until dry. Transfer the dried oats to a high-speed blender or food processor and process into a flour-like consistency. Sift the flour to remove any large, hard crumbs. Store in the refrigerator.

For an even easier way to make oat flour, place raw rolled oat flakes or old-fashioned rolled oats in a food processor and pulse until finely ground.

Buckwheat Flour. To make buckwheat flour, soak whole raw buckwheat groats in cold filtered water for 15 to 30 minutes (no longer!). After rinsing and draining, transfer the buckwheat to a mesh-lined dehydrator tray and dehydrate for 12 to 24 hours, or until dry. Alternatively, transfer the buckwheat to a parchment paper-lined baking sheet and bake at 200°F for 2 to 3 hours, or until dry. Transfer the dried buckwheat to a high-speed blender or food processor and process into a flour-like consistency. Sift the four to remove any large, hard crumbs. Store in the refrigerator.

Buckwheat Flour. To make buckwheat flour, soak whole raw buckwheat groats in cold filtered water for 15 to 30 minutes (no longer!). After rinsing and draining, transfer the buckwheat to a mesh-lined dehydrator tray and dehydrate for 12 to 24 hours, or until dry. Alternatively, transfer the buckwheat to a parchment paper-lined baking sheet and bake at 200°F for 2 to 3 hours, or until dry. Transfer the dried buckwheat to a high-speed blender or food processor and process into a flour-like consistency. Sift the four to remove any large, hard crumbs. Store in the refrigerator.

Cashew Flour. To make cashew flour, place raw cashews in the bowl of a food processor and pulse until very finely ground. Store in the refrigerator.

Cashew Flour. To make cashew flour, place raw cashews in the bowl of a food processor and pulse until very finely ground. Store in the refrigerator.

Coconut oil and cacao butter both need to be melted before being put to use in any recipe, unless otherwise specified. The amounts of coconut oil and cacao butter I call for in recipes are always measured after melting.

Coconut Oil and Butter. To melt coconut oil, you can place the whole jar in a warm dehydrator for 10 to 20 minutes, or until melted, or set it in a bowl of hot water (making sure it stands upright). If you only need a small amount, melt a couple spoonfuls in a double boiler over very low heat, stirring constantly, or in a small bowl placed carefully in a larger bowl of hot water (making sure no water gets into the smaller bowl). Unused melted coconut oil can simply be poured back into the original jar.

Coconut Oil and Butter. To melt coconut oil, you can place the whole jar in a warm dehydrator for 10 to 20 minutes, or until melted, or set it in a bowl of hot water (making sure it stands upright). If you only need a small amount, melt a couple spoonfuls in a double boiler over very low heat, stirring constantly, or in a small bowl placed carefully in a larger bowl of hot water (making sure no water gets into the smaller bowl). Unused melted coconut oil can simply be poured back into the original jar.

Coconut butter can also be softened before using; it’s not always necessary, but it makes it easier to mix and measure. To do so, place the whole jar in a warm dehydrator for 15 to 30 minutes, or until softened, or set it in a bowl of hot water (making sure it stands upright). If you only need a small amount, melt a few spoonfuls in a double boiler over very low heat, stirring often, or in a small bowl placed carefully in a larger bowl of hot water (making sure no water gets into the smaller bowl). Unused softened coconut butter can simply be transferred back into the original jar.

Cacao Butter. To melt cacao butter, chop it roughly with a sharp knife, transfer it to a bowl, and place it in a warm dehydrator for 20 to 30 minutes, or until melted, stirring occasionally. Alternatively, you can melt cacao butter in a double boiler over very low heat, stirring constantly, or place it in a jar and set it in a bowl of hot water (making sure it stands upright). Unused melted cacao butter can be chilled until solid, then transferred in a chunk back to its original container.

Cacao Butter. To melt cacao butter, chop it roughly with a sharp knife, transfer it to a bowl, and place it in a warm dehydrator for 20 to 30 minutes, or until melted, stirring occasionally. Alternatively, you can melt cacao butter in a double boiler over very low heat, stirring constantly, or place it in a jar and set it in a bowl of hot water (making sure it stands upright). Unused melted cacao butter can be chilled until solid, then transferred in a chunk back to its original container.

I keep a stash of peeled, frozen bananas in my freezer at all times. Let your bananas get as ripe as possible (with plenty of dark brown spots on the skin) before peeling and arranging them on a baking sheet. Freeze them for at least 8 hours or overnight and then transfer them to a plastic zip-top bag to store in the freezer. The more ripe your bananas are when you freeze them, the more natural sweetness they’ll lend to your recipes.

If you are able to acquire Irish moss (see Resources, page 228), it is a type of seaweed with multiple uses in raw food preparation. You’ll find it makes an excellent addition to raw breads and pastries, making them lighter, fluffier, and almost baked-tasting. Before using it, you must turn the Irish moss into a gel to make it easier to pulse or blend into things. (See Cutting the Fat on page 18.)

To make Irish moss gel, place 1 cup packed Irish moss in a large bowl and cover with 3 to 4 cups cold filtered water. Soak for 3 to 4 hours, then rinse and drain well. Combine the soaked Irish moss and 1/2 cup cold filtered water in a high-speed blender and blend until smooth (you’ll probably need to use the tamper for this). Add additional water, 1 to 2 tablespoons at a time, as needed to blend, only adding the bare minimum amount necessary to make a smooth purée. Use right away or transfer the mixture to a small container and refrigerate for up to a week.

Here is a comprehensive list of ingredients for a raw vegan pantry. Remember, you certainly don’t need to have everything on this list to begin experimenting with raw food. Take inventory of your fridge and pantry, then flip though this book, keeping an eye out for ingredients you have. You’re sure to find numerous things you can whip up, especially if you take note of the substitution options offered at the end of every recipe.

Fresh:

Apples

Bananas

Berries (assorted)

Cherries

Citrus fruits (lemons, limes, oranges)

Grapes

Kiwis

Mangos

Melons (assorted)

Peaches

Pears

Pineapple

Frozen:

Berries (assorted)

Cherries

Mangos

Peaches

Pineapple

Dried:

Dates

Raisins

Cranberries

Figs

Apricots

Fresh:

Asparagus

Avocados

Bell peppers

Broccoli

Carrots

Cauliflower

Celery

Corn

Cucumbers

Garlic

Ginger

Leafy greens (assorted)

Mushrooms

Onions

Sprouts

Squash (summer and winter)

Tomatoes (fresh and sundried)

Frozen:

Corn

Peas

Almonds

Cashews

Macadamia nuts

Pecans

Walnuts

Brazil nuts

Hazelnuts

Pine nuts

Pistachios

Coconuts: fresh young Thai coconuts, unsweetened shredded coconut, coconut water

Ground flaxseed (flax meal)

Chia seeds

Sesame seeds

Hempseeds

Sunflower seeds

Whole golden flaxseed

Pumpkin seeds

Almond butter

Coconut butter

Cashew butter

Tahini (sesame seed butter)

Unrefined virgin coconut oil

Extra-virgin olive oil

Toasted sesame oil

Nut oils (assorted)

Seed oils (flax, hemp)

Almond flour

Buckwheat flour

Oat flour

Coconut flour

Cashew flour

Wild rice

Buckwheat groats

Oat groats

Raw oat flakes, old-fashioned rolled oats

Raw agave nectar or coconut nectar

Dried dates (Medjool and/or deglet noor)

Pure maple syrup (grade B)

Coconut palm sugar

Stevia (liquid and/or powder)

Dried:

Basil

Black pepper

Cardamom

Cayenne pepper

Chili powder

Cinnamon

Coriander

Crushed red pepper flakes

Cumin (ground)

Cumin seeds

Curry powder

Fennel seeds

Garlic powder

Onion powder

Oregano

Paprika

Pumpkin pie spice

Rosemary

Saffron (optional)

Sage

Sea salt

Thyme

Turmeric

Fresh:

Flat-leaf parsley

Cilantro

Mint

Miso paste (preferably white)

Nutritional yeast

Tamari soy sauce, nama shoyu, or liquid aminos

Real vanilla extract

Other flavor extracts (almond, coffee, etc.)

Vinegars (assorted)

Raw cacao powder, carob powder, or unsweetened cocoa powder

Cacao butter

Cacao nibs

Gojiberries, mulberries, and/or goldenberries

Hemp or sprouted brown rice protein powder

Maca powder

Mesquite powder

Powdered greens supplement

Spirulina powder

Wheatgrass juice powder

Dairy-free probiotic powder

Sea vegetables: nori, dulse flakes, kelp noodles, Irish moss

Lecithin (soy or sunflower)

Jarred olives, capers, and chipotle chiles

Dried beans and lentils (for sprouting)

Coffee and/or tea

Good-quality storebought nondairy milks, bottled lemon juice, nondairy chocolate chips, and other convenience foods

There are some basic facts about the recipe ingredients that hold true for all the recipes, unless otherwise specified. Keep these general points in mind as you prepare the recipes:

All ingredients used are raw and organic. If raw or organic items are not available to you, however, you can substitute a non-raw, conventional alternative.

All ingredients used are raw and organic. If raw or organic items are not available to you, however, you can substitute a non-raw, conventional alternative.

All oils are cold-pressed and virgin, with the exception of sesame oil.

All oils are cold-pressed and virgin, with the exception of sesame oil.

Dehydration is conducted between 105 and 115°F (40 to 46°C).

Dehydration is conducted between 105 and 115°F (40 to 46°C).