HE PREHISTORIC CAVE PAINTINGS OF FRANCE AND SPAIN ARE AMONG the most ancient works of art that we have. The human beings in these paintings are usually crude stick figures that the artists do not seem to have considered very important. The animals are painted with far more care and passion. The first clearly identifiable religious shrines in history are at Çatal Huyuk in Anatolia and date from around the middle of the seventh millennium BCE. They were dedicated to animals, especially bulls, but also to vultures, foxes, and others. The Egyptians worshipped their gods as incarnated in cats, ibises, bulls, and many other creatures. Over millennia, anthropomorphic goddesses and gods slowly replaced the animal deities. The archaic divinities accompanied their more human successors, often as mascots or alternate forms. Athena, for example, was pictured with an owl, and Zeus with an eagle; Odin was accompanied by ravens and by wolves. The monkey Hanuman, who fought alongside the hero Rama in the epic Ramayana, is now perhaps the most popular figure in the Hindu pantheon. In folktales and fairy tales throughout the world, the human hero is often guided or advised by an animal companion. An aura of secret wisdom at times seems to embrace all animals, perhaps a legacy of these bestial deities. Their apparent lack of speech contains more wisdom than our incessant, and often futile, talk. The gaze of many animals, from insects to tigers, often seems more intent and confident than that of any human being. A very few animals, such as the raven or salmon have, however, an especially consistent reputation for wisdom.

HE PREHISTORIC CAVE PAINTINGS OF FRANCE AND SPAIN ARE AMONG the most ancient works of art that we have. The human beings in these paintings are usually crude stick figures that the artists do not seem to have considered very important. The animals are painted with far more care and passion. The first clearly identifiable religious shrines in history are at Çatal Huyuk in Anatolia and date from around the middle of the seventh millennium BCE. They were dedicated to animals, especially bulls, but also to vultures, foxes, and others. The Egyptians worshipped their gods as incarnated in cats, ibises, bulls, and many other creatures. Over millennia, anthropomorphic goddesses and gods slowly replaced the animal deities. The archaic divinities accompanied their more human successors, often as mascots or alternate forms. Athena, for example, was pictured with an owl, and Zeus with an eagle; Odin was accompanied by ravens and by wolves. The monkey Hanuman, who fought alongside the hero Rama in the epic Ramayana, is now perhaps the most popular figure in the Hindu pantheon. In folktales and fairy tales throughout the world, the human hero is often guided or advised by an animal companion. An aura of secret wisdom at times seems to embrace all animals, perhaps a legacy of these bestial deities. Their apparent lack of speech contains more wisdom than our incessant, and often futile, talk. The gaze of many animals, from insects to tigers, often seems more intent and confident than that of any human being. A very few animals, such as the raven or salmon have, however, an especially consistent reputation for wisdom.

The snake, whose reputation for wisdom had already been established when the tale of Adam and Eve was written down, might have been included in this chapter. It has been placed instead in chapter 13 on “Cthonic Animals.” The elephant, another candidate for inclusion here, is in Chapter 17 on “Behemoths.”

BEE AND WASP

Ask the wild bee what the Druids knew.

—SCOTTISH SAYING

Our word “bee” ultimately goes back to the Indo-European “bhi,” meaning “to quiver.” The same root is in the Greek “bios,” meaning “life.” A quiver is the motion of spirit, a pulse or a breath. Life is a sort of “buzz,” a humming in the void. Bees appear primordial. In ancient Egypt, bees sometimes represented the soul. People said that bees were born from the tears of the sun god, Ra, or, later, from those of Christ.

Bees do not fly directly from one place to another. Instead, they often hover pensively in the air. They build complex homes, almost like human cities. Above all else, their ability to produce honey and wax has always seemed wondrous. In Plato’s dialogue “Phaedo,” Socrates suggested that those who live as good citizens might be reincarnated as bees or other social insects. He meant this transformation, of course, to be a reward. It is small wonder that author Maurice Maeterlink, in the early twentieth century, considered bees the most intelligent of animals next to humankind.

In Georgics, Virgil bestowed great praise on the bees, hoping to shame his decadent countrymen in Rome:

Alone of living things they hold their young

In common, nor have individual homes:

They pass their lives beneath the might of law:

They know the patriot’s zeal, and reverence

For household gods: mindful of frosts to come,

They toil through summer, garnering their grains

Into the common store. While some keep watch…

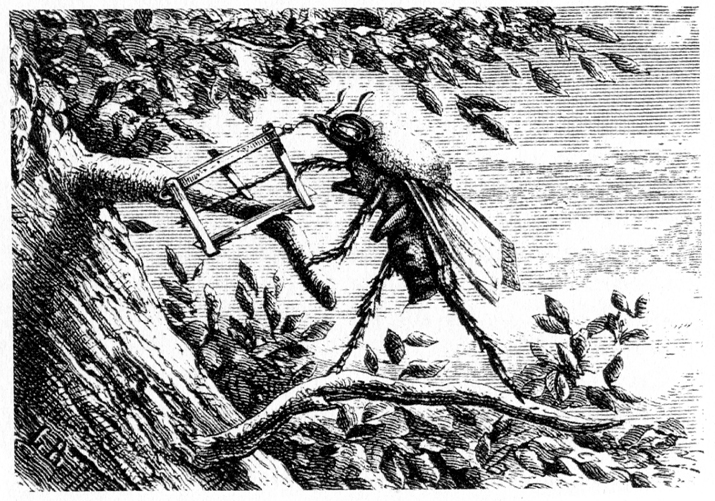

A worker bee.

(Drawn by Ludwig Becker)

According to Virgil, bees neither lost their minds through love nor weakened their bodies through sexual excess. They were spared the pains and hazards of pregnancy, since their young spring spontaneously from plants. Most of all, Virgil admired the patriotism of the bees. Spiders, hornets, worms, and other menaces constantly threatened their hives, yet the bees never ceased their vigilance. The individuals sacrificed their lives but the community survived.

Aristotle, writing in The Generation of Animals, had considered the generation of bees “a great puzzle,” but he suggested various possible means of reproduction. One was that they drew their young from various flowers, while others included copulation and spontaneous generation. Virgil told us that the Egyptians near Canopus by the Nile had a rite in which priests would lead a two-year old bull into a small room. Priests would club the animal to death then continue to pound the flesh, taking care not to pierce the skin. Then they covered the body with thyme, bay and other spices. A short time later, bees emerged from the body.

The practice began after the nymph Eurydice, beloved of Orpheus, departed from her husband into the underworld. The bees died, and they could only be brought back when the spirits of the lovers were placated by the sacrifice of an ox. Persephone, queen of the dead in Greco-Roman mythology, returned yearly from the underworld as vegetation; Eurydice returned as a swarm of bees. Initiates into the mysteries of Dionysus, god of wine and religious ecstasy, had another interpretation of the ceremony; Dionysus, in the form of an ox, had been torn apart by Titans and was reborn as a bee.

Like agriculture, beekeeping is very seasonal. Many bees die and hives lie virtually dormant in winter. In the ancient and Medieval worlds, farmers and their children would watch carefully in spring for signs that bees were beginning to swarm; then people would gather and follow the bees. They would set up attractive new hives and beat on kettles, believing that the noise would help the bees to settle down. In autumn, they would harvest the honey.

Bees are so beloved that people have generally forgiven their painful sting. In a fable of Aesop, however, the bees begged Zeus for stings in order to protect their honey. Zeus was displeased at their covetousness. He granted the request but added that bees had to die whenever they used their stings. Honey bees really do pass away on stinging, since they cannot remove the stinger without tearing their abdomens. (That is not true of other varieties.) The individual dies for the hive; even a person stung by bees might be moved to forgiveness by the sacrifice.

Sometimes armies have set loose bees against their enemies. Montaigne reported in “Apology for Raymond Sebond” that, when the Portuguese were besieging the town of Tamly, the defenders brought a great number of hives and placed them around the wall. Next, they set fires to drive out the bees into the invading host. The enemy was completely routed. On returning, they found that not a single bee had been lost. He does not record how they counted the bees.

The keeping of hives for honey bees developed simultaneously in several centers of the ancient world, including Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, and China. It reached a high degree of sophistication by the first millennium CE, but bees, even today, can’t be called “domesticated.” Even in hives made by human beings, bees always retain a life of their own. Aelian, writing in the first century CE, reported that bees knew when frost and rain were coming. When bees remained close to their hives, beekeepers warned the farmers to expect harsh weather. If the bees know this, what else might they know as well?

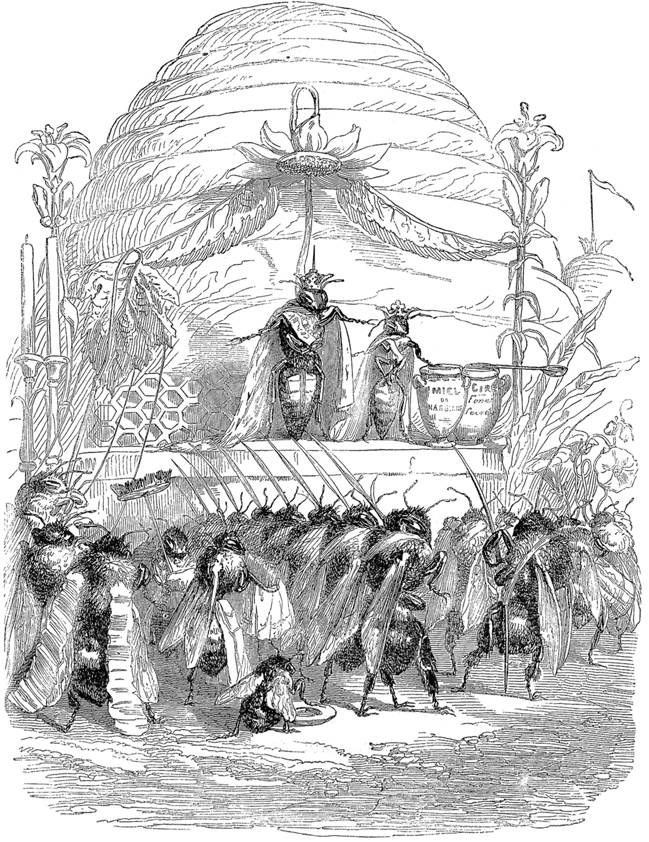

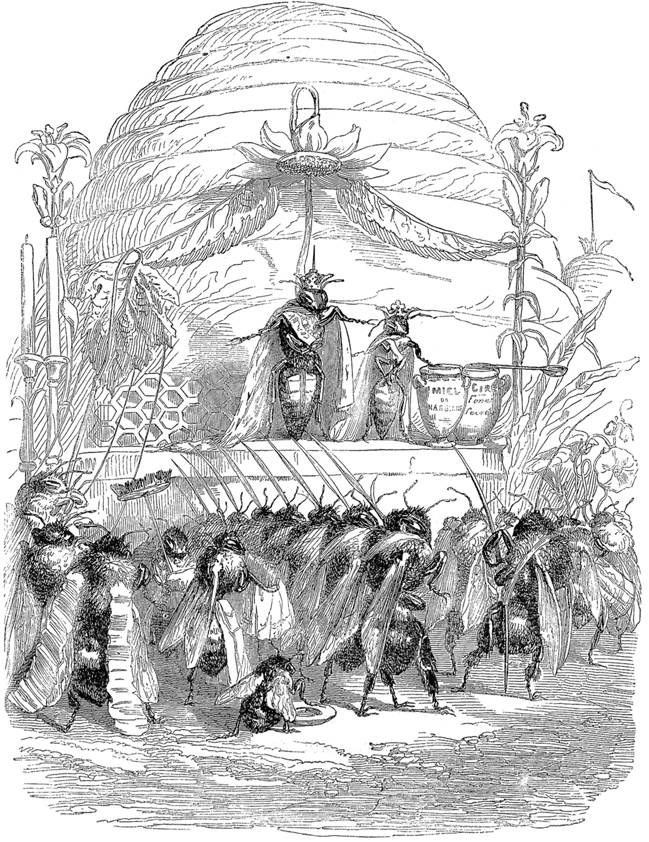

The bees here have formed a feudal state, in which the monarch looks on as soldiers and workers parade past.

{J. J. Grandville, from Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux, 1842)

Swarms of bees were closely watched as portents in ancient Rome. Priests used the size and direction of a swarm to foretell fortunes during war. Māra, the Hindu god of love, has a bowstring made of bees, perhaps because discovering love is a bit like a swarm of bees setting off to find a new home. Herodotus, the Greek historian, tells how Onesilus once led a revolt of the Cyprians against the Persian Empire of King Darius. After Onesilus was killed in battle, the people of the Cypriot city of Amathus, who had sided with the Persians, cut off his head and placed it over one of their city gates. After a while, the skull became hollow, and a swarm of bees filled the head with honeycomb. The Amathusians consulted an oracle, who told them to take down the head, bury it, and offer sacrifices every year to Onesilus.

Country people in Europe and North America have traditionally notified the bees when the owner of their property died. There is a description of this ceremony in Lark Rise to Candleford, a fictionalized account by Flora Thompson of her childhood in a poor rural family in England during the latter nineteenth century. After her husband’s death, his widow, Queenie, would knock on each hive, as though at a door, and say, “Bees, bless, your master’s dead, and now you must work for your missis.” She told young Flora that, if this were not done, all of the bees would have died. At times, rural people would tell the bees a lot more about affairs of the household, and it is not terribly hard to understand why. Working alone in the fields, one might easily feel an urge to talk. If no other people were around, one might speak to whatever seemed most human – that is, to the bees. The word “bee” is sometimes used to refer to activities where people work and talk, for example a “quilting bee” or a “husking bee.” A rumor is sometimes referred to as a “buzz.” European peasants have sometimes believed that ancestors return to their property as bees.

People have always considered the honey of bees a divine food. Zeus was raised on the island of Crete, drinking the milk of the fairy goat Amalthea and eating the honey of the bee Melissa. John the Baptist “lived on locusts and wild honey” (Matthew 3:4; Mark 1: 6-7). Pliny the Elder wrote that bees placed honey in the mouth of Plato when he was a child, foretelling his later eloquence. The same was later said of Saint Ambrose, Saint Anthony, and other holy men. Cesaire de Hesterbach reported, in the early thirteenth century, that a peasant once placed the Eucharist in a hive, hoping it would inspire the bees to produce more honey. Later, he found that the bees had made a little chapel of wax. It contained an altar on which lay a tiny chalice with the Host.

A queen bee giving out bread and honey to her children in the hive.

(Illustration by J. J. Grandville, from Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux, 1842)

It is hard for people to think of bees as individuals, and even beekeepers can hardly ever distinguish between them. Only the queen stands out from the rest. Social insects such as ants and bees may be the inspiration for hierarchies in which the individual is subordinate to the state, from ancient Sparta to the Soviet Union. Napoleon took the bee as his emblem. People have constantly aspired to emulate the bees.

Topsell, in the mid-seventeenth century, described the society of bees as an ideal monarchy. The King (now known to be female, and called “the Queen”) was set apart by his size and royal bearing. His subjects all loved and obeyed him. The court of bees also contained viceroys, ambassadors, orators, soldiers, pipers, trumpeters, watchmen, scouts, sentinels, and far more.

Thomas Muffet, who collaborated with Topsell has told us that bees “are not misshapen, crook-legged any way, pot-bellied, over close-kneed, bulb-cheeked, great mouthed, lean-chopped, rude foreheads or barren, as many great ladies and noble women are, who have lost the faculty of generation.” He went on to say that in the “democratical state” of the bees, everyone is employed in some honest labor. The bees were generated by the putrefaction of animals such as oxen, with the kings and the nobility created from the brain and the commoners from the other parts. Muffet added that bees could not endure the presence of lechers, menstruating women, or those who use perfumes.

For others of the Renaissance, those bees seemed a little too perfect, too virtuous, and too austere. Bernard Mandeville, a Dutch physician, satirized them in The Fable of the Bees (1724). The bees appealed to Jupiter to organize their state according to the ideals of perfect virtue. They got rid of the corrupt officials and lazy courtiers. The trouble was that the virtuous replacements didn’t know how to get things done. Since the bees no longer produced luxuries like honey, their economy collapsed. Since the bees lived only for peace, they forgot how to fight. Finally, a few melancholy survivors withdrew into a hollow oak to await their end.

The priestesses of the goddesses Demeter and Rhea had been known in ancient Greece as “Melissae” or bees, and the female name hints that, in remote antiquity, people may have realized that the bees are a matriarchy. If so, that knowledge was forgotten until the start of the modern era. It was not until 1637 that the Dutch scientist, Jan Swammerdam, examined the bees under a microscope, to learn that the so-called “King” was really a Queen. The bees could no longer be used as a model for a perfect kingship.

For the French author Maurice Maeterlinck, around the start of the twentieth century, the religion of the bees was that of progress. “The god of the bees is the future,” he wrote in Life of the Bee. “There is a strange duality in the character of the bee. In the heart of the hive, all help and love each other … Wound one of them, and a thousand will sacrifice themselves to avenge the injury. But outside the hive, they no longer recognize each other.” The bees had become radical socialists, living only for their cause.

During World War II, the distinguished scientist Karl von Frisch was studying bees at the University of Munich. He had been classified as one quarter Jewish by the Nazi regime, which normally would have deprived him of his job. A disease began to kill off the bees in Germany, threatening the orchards, so the government allowed him to continue his work. Pouring his frustrations into work, the introverted von Frisch began to decipher the communication of the bees. They indicate the direction and distance of food by dances within the hive. This remarkable story, though completely true, reads almost like a fairy tale of grateful animals. The scientist seemed to have a covenant, a special intimacy, with bees. As he worked to rescue bees, they saved him. He was then initiated into their society and their speech. Of course, there is a difference. Unlike the heroes of fairy tales, von Frisch published the secrets of bees to the world.

Still, though a bit of the language of bees may be deciphered, only bees themselves may speak it. A person could certainly try doing the dance of bees, but that would be art. It would not impart information. We teach other animals such as chimpanzees to use human language. Then, much of the time, we think of them as imperfect human beings. But people are also, as Virgil knew long ago, imperfect bees.

For some reason, people pair related animals as opposites: the rat and the mouse, the dog and the wolf, the lion and the tiger. The bee is constantly paired with the wasp, related creatures that live in nests instead of hives. One legend from Poland told that when God created bees, the devil made wasps in a failed attempt at imitation. In a Romanian legend, a peddler persuaded a gypsy to exchange a bee for a wasp by saying that the wasp was larger and would make more honey. All the gypsy got for his greed was a sting.

While the bee is a symbol of peace, the wasp is associated with conflict and war. The Greek comic poet Aristophanes, in his play “Wasps,” compared these insects to jurors, since both came in annoying swarms. Saint Paul seemed to conceive of death itself as an insect, probably a wasp, since he asked, “Death, where is thy sting?” (1 Corinthians 15:55). At the end of the Middle Ages, the wasp was frequently the form in which the soul of a witch flew about at night.

A fashionable young lady with a “wasp waist,” who is charming but also dangerous

(Illustration by J. J. Grandville, from Les Animaux, 1868)

Some cultures, however, have admired the martial qualities of wasps. Greek warriors went off to battle with wasps emblazoned on their shields. Among Native Americans and Africans, enduring the stings of wasps can be a test in initiation ceremonies. The wasp was a form often taken by Native American shamans. The wasp killing a grasshopper became a Medieval symbol of Christ triumphing over the Devil.

The mason wasp is a deity of the Ila people in Zambia. They tell that once all the Earth was cold, so the animals sent an embassy up to heaven to bring back fire. The vulture, eagle, and crow all died on the journey. Only the wasp arrived to plead, successfully, with God. Because he brought fire to the hearths, the wasp now makes his nest in chimneys.

Today in the United States, the acronym “WASP” stands for “White Anglo-Saxon Protestant.” The term is usually used in a derogatory way. It suggests a combination of snobbery, and viciousness. A wasp gives little warning yet has a terrible sting. The term “wasp waist” is used to describe people, especially women, who have what is also called an “hourglass figure.” That suggests beauty that is obtained in a very artificial, calculating sort of way. But if the bee were not thought of as holy, perhaps the wasp would not be so maligned.

CROW, RAVEN, AND ROOK

One is for sorrow.

Two is for mirth.

Three is a wedding.

Four is a birth.

—AMERICAN NURSERY RHYME about crows.

Corvids, particularly ravens and crows, are creatures of paradox. Their black plumage, slouching posture, and love of carrion sometimes make them appear morbid, yet few if any other birds behave in such a playful manner. Even their voices are at once harsh and spirited. Ravens are much larger than crows. They are relatively solitary and make their nests far from human beings, while crows generally move about in flocks and are attracted to human settlements by the promise of food. Both, however, are associated with death and share a reputation as birds of prophecy. They are also monogamous, making them symbols of conjugal fidelity. People probably did not distinguish sharply between ravens, crows, rooks, and many related birds in the ancient world, and they often appear much the same in heraldry as well. The blue jay is one corvid that is not black, but it shares their reputation as a trickster among the Chinook and other Native Americans along the northwest coast of the United States and Canada.

The ambivalent character of ravens is apparent in the Bible where, though “unclean” birds, they sometimes appear to have a special intimacy with God. After the Flood had raged for forty days, Noah sent out a raven to find land. It flew back and forth until the waters receded but did not return (Genesis 8: 6-8). Later, however, ravens fed the prophet Elijah every morning and evening when he had fled from Ahab into the wilderness (1 Kings 17:4). In the Talmud, when Abel had been slain, Adam and Eve, who had no experience with death, did not know what do. A raven slew another of its own kind, dug a hole, and performed a burial, thus demonstrating to the first man and woman how the dead ought to be treated. In gratitude, God feeds the children of the ravens, which are born white, until they grow black plumage and can be recognized by their parents.

There is a similar story in the Koran. When Cain had killed Abel, he did not know what to do with his brother’s body, and carried it around on his shoulders, for no human being had ever died before. Then Cain saw a raven scratch the ground, showing how people should bury their dead. On giving Abel a proper burial, he was able to repent and attain divine forgiveness.

The Romans viewed birds as mediators between gods and human beings, at times in homey as well as solemn ways. Pliny the Elder recounts a story of a raven, hatched on the roof of a temple in Rome, which flew down to the shop of a shoemaker. The owner, wishing to please the gods, welcomed the bird. By watching the customers, the raven soon learned to talk. Every day he flew to the podium across from the forum and greeted the Emperor Tiberius by name. Then he flew around and said “hello” to various men and women before returning to the shop. One day a neighbor killed the raven, perhaps thinking the bird had left some droppings on his shoes. The people of Rome became incensed and lynched the man. Then they gave the raven a splendid funeral, in which Ethiopian slaves carried the bier, and many people left flowers along the path.

On the European continent, where there are few vultures to compete with, corvids would hover above a battlefield and later descend to eat the corpses. Two ravens perched on the shoulders of the Norse Odin, who was intimately associated with battles. They were named Hugin (thought) and Munin (memory), and they flew over the world to bring news to the god. The Celtic war goddess Morrigan would take the form of a raven or crow and come as a herald of death. When the hero Cuchulainn had been mortally wounded, he tied himself to a tree and stood with his sword in hand. His enemies watched from a distance but did not dare approach until a crow, the goddess Babd, perched on his shoulder. In one of many versions collected from oral traditions, the traditional British ballad “The Twa Corbies” begins:

There were three ravens on a tre,

They were as black as black might be:

The one of them said to his mate,

“Where shall we our breakfast take?”—

“Downie in yonder green field,

There lies a knight slain under his shield …

The ravens find they must take their meal elsewhere, for this knight is guarded by his dogs, hawks, and wife. In many wars, however, it gave soldiers a sense of foreboding to see corvids following their armies and hovering over the battlefield.

Some major themes such as prophecy and death run through the lore of ravens among Europeans, Asians, and Native Americans, but the tales of the Indians are richest in humor. Among the Haida Indians and related tribes of the American and Canadian Northwest Coast, Raven is at once a sage and trickster. One widely disseminated tale, which has many variants, begins at a time when there was no light in the world, for all of the light was held in a box kept in the house of the Chief of Heaven. Raven conceived a plan to steal the light. First, Raven turned into a cedar leaf floating in a stream where the daughter of the Chief of Heaven went to drink. On swallowing the leaf, she became pregnant, and then gave birth to Raven, in the form of an infant boy. After playing for several days in the house of the Chief, Raven began to cry and clamor for the box that held the light. The Chief, who was charmed by his young grandson, let him hold the box, at which point Raven immediately put on wings and carried the container out of the Chief’s lodge into the sky. An eagle pursued him, and Raven swerved to escape its talons, dropping half of the light, which broke into many fragments, becoming the moon and stars. Finally, when he had reached the edge of the world, Raven let go of the remaining light to create the sun.

It is possible that this story may have been influenced by Christianity, since it has many structural parallels with the story of Jesus. The Chief of Heaven corresponds to God the father, while his daughter is reminiscent of Mary, and Raven himself may be Christ, referred to in the Bible as “the light of the world” (John: 8:12). But in such tales, the identity of Raven—with his cosmic powers and many changes of form—becomes so abstract that he seems less an animal, or even a person, than an embodiment of celestial energy. The myths of Raven often resemble accounts of contemporary physicists, who describe how the cosmos was created, in narratives full of mysterious forces and alternate universes.

Corvids have always figured prominently in poetry, and one of the most famous examples is Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “The Raven” (1845). The narrator asked a raven that had flown into his chamber whether he could be reunited with his deceased beloved:

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil! prophet still, if bird or devil!—

Whether Tempest sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted—

On this home by Horror haunted—tell me truly, I implore—

Is there— is there balm in Gilead? — tell me— tell me, I implore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

The bird gazed imposingly, as befitted a messenger from the world of spirits, but revealed nothing.

In “Vincente the Raven” (1941) Portuguese author Miguel Torga tells a story of the raven that accompanied Noah. Vincente became increasingly restless. Though not personally mistreated, he grew angry that the animals and the earth should be punished for the crimes of humankind. At last he left the Ark unbidden, perched on the peak of Mount Ararat, and called out his defiance to God. The flood continued to rise, but Vincente refused to leave. God realized that, should he drown Vincente, his creation would no longer be complete, and so he finally relented and reluctantly allowed the water to recede.

In the collection of Medieval Welsh tales known as The Mabinogion, the giant Bran (whose name means “Crow”), traditionally depicted with a raven, had been mortally wounded while leading an army of Britons against the Irish. At his command, his followers behead him and carry the head to the site of the Tower of London for burial, so that it might serve as a charm to protect Britain. This is the remote origin of the legend that Britain will never be successfully invaded as long as ravens remain in the Tower. Such pagan legends eventually led to the demonization of crows and ravens at the end of the Middle Ages, when they were often either witches’ familiars or a form in which witches flew about at night.

Contemporary culture is full of urban legends of vanishing hitchhikers and bigfoots, but these generally do not address momentous themes such as the destiny of a people, and so we hesitate to call them “myths.” One story that does, perhaps, merit such a designation is that of the ravens in the Tower of London. At least six ravens are kept on the grounds of the Tower of London at all times, because of a reputedly “ancient” prophecy that “Britain will fall” if they leave. In fact, the ravens were brought to the Tower of London in 1883, to serve as props for tales of Gothic horror told by Beefeaters to tourists. A Yeoman Warder might intone, “… and, after they chopped off her head, ravens descended to pluck out her eyes,” and a real raven would be croaking in the background. The legend that ravens protect Britain from catastrophe actually dates only from 1944, when they were used as unofficial spotters for enemy bombs and planes. But, since the story still addresses visceral anxieties, it continues to circulate and develop. Since it encourages respect for ravens, as avatars of the natural world, we should be glad.

Rooks share the reputation of the more illustrious ravens for wisdom, but they are more approachable. In Precious Bane by Mary Webb (1924), a novel of peasant life in the English countryside during the early nineteenth century, a family told the rooks when the master of the house had died, so that the birds would not bring ill luck by deserting the home. The new master followed the ceremony cynically, remarking quietly that he was very fond of “rooky pie.” The birds rose and circled thoughtfully but then returned to their branch, letting the people know they intended to stay. Their hesitation, however, left a sense of foreboding, and the farm was soon struck by disaster.

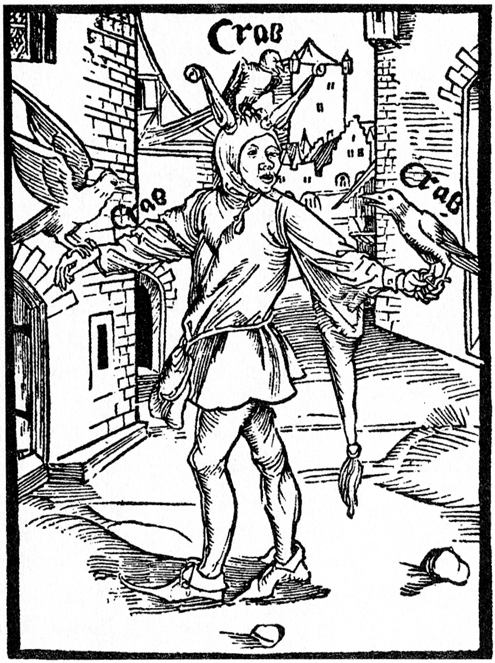

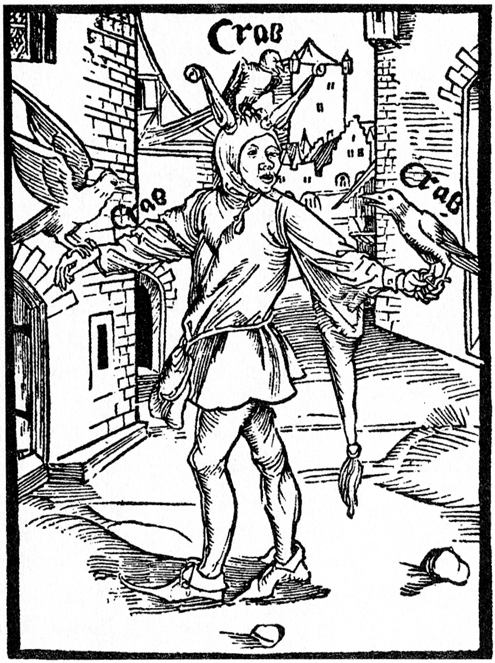

The raven tells the fool “cras,” Latin for “tomorrow,” leading him to procrastinate.

(Albrecht Dürer’s illustration for Sebastion Brandt’s Ship of Fools, 1494)

The crow even teaches people how to die in a myth of the Murinbata, an aboriginal people of Australia. Crab demonstrated what she believed was the best way to die by going to a hole and casting off her wrinkled shell. Then she waited for a new one, so she might be reborn. Crow responded that there was a quicker, more efficient way to die, and immediately fell over. The lesson here was that the reality of death should be accepted without equivocation.

Herodotus wrote that two “black doves” had flown from Thebes in Egypt; one settles in Lybia while the other goes on to Greece and settles in the sacred grove of Dodona. It rustles the leaves and brings forth the prophetic voice of Zeus. The Greek historian believed the birds were originally dark-skinned priestesses, but scholars have suggested that they may have been crows or ravens.

Closely bound with the wisdom of corvids is their reputation for longevity, and they can indeed live for decades. In The Birds, by the Greek comic playwright Aristophanes, crows are said to live five times the life of a human being. In a dialogue entitled “On the Use of Reason by so-called ‘Irrational’ Animals” by Plutarch, the wise pig Gryllus states that crows, upon losing a mate, will remain faithful for the remainder of their lives, seven times that of a human being. Precisely because of this reputation for fidelity, however, the Greeks and Romans considered a single crow at a wedding to be an omen of the possible death of one partner.

The god Apollo once took the form of a crow when he fled to Egypt to escape the serpent Typhon. The crow remained sacred to Apollo, but the relationship of the god to corvids was not without ambivalence. Ovid tells in Fasti that once Phoebus Apollo had been preparing a solemn feast for Jupiter and told a raven to bring some water from a stream. The raven flew off with a golden bowl but was distracted by the sight of a fig tree. Finding the fruits unfit to eat, the raven sat beneath the tree and waited for them to ripen. He then returned with a snake that he claimed had blocked the water, but the god saw through this lie. As punishment for lateness and deceit, the god later decreed that the raven would not be able to drink from any spring until figs had ripened on their trees. The god placed a constellation depicting a raven, snake, and bowl in the sky, and, in the springtime, the voice of the raven is still harsh from thirst. The call of the raven was often said to be “cras,” Latin for “tomorrow,” and the raven often symbolized a procrastinator during the Renaissance.

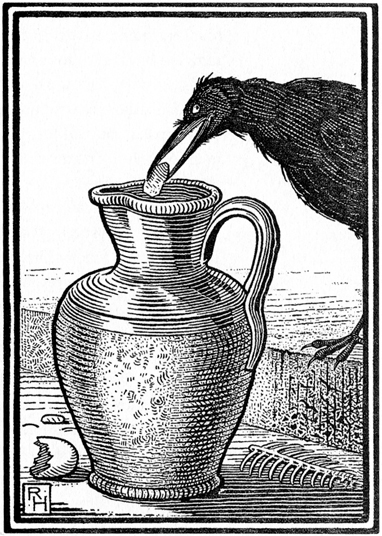

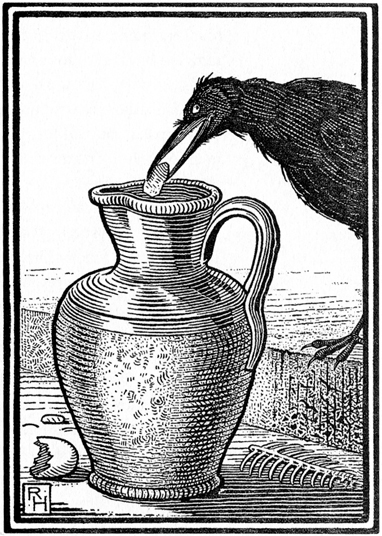

The intelligence of crows and ravens has amazed people since ancient times. A fable about their smart feats is In “The Crow and the Pitcher,” traditionally attributed to the legendary Aesop, a thirsty crow came upon a pitcher of water but was unable to reach inside and drink. The bird began to pick up pebbles and drop them one by one into the pitcher until the water had risen to the top. The usual moral of this story is that “Necessity is the mother of invention.” This is one anecdote that could well be based on fairly accurate observations. That particular feat was long considered impossible for birds, but in 2009 several rooks in a Cambridge, England aviary figured out how to make the water level rise by dropping pebbles in a test tube.

Aesop’s fable “The Crow and the Pitcher.”

(Illustration by Richard Heighway)

In China, crows can be birds of ill omen but also symbols of fidelity in love. A collection of Taoist lore usually entitled Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, written in the latter seventeenth century by Po Songling, tells of a young man from Hunan named Yü Jung who failed his civil service examinations and was consequently unable to find employment. Desperate and hungry, Yü Jung stopped at the shrine of Wu Wang, the guardian of crows, and prayed. After a while, the attendant of the temple approached and offered him a position in the order of the black robes. Delighted to have found a way to earn his living, Yü Jung accepted. The attendant gave him a black garment, and, after putting it on, Yü Jung was transformed into a crow. Soon he married a young crow named Chu Ch’ing, who taught him the corvid ways. Unfortunately, he proved too impetuous, and a mariner shot him. The others crows churned up the waters and made the mariner’s boat capsize, but Yü Jung suddenly found himself once again in human form, lying near death on the temple floor. At first he thought the whole adventure had been a dream, but he could not forget the joys he had known as a crow. Eventually, he passed his exams and became prosperous, but Yü Jung continued to visit the temple of Wu Wang and make offerings to the crows. Finally, when he sacrificed a sheep, Chu Ch’ing came to him and returned his black robe, and Yü Jung again took on corvid form.

In the story “Herd Boy and the Weaving Maiden,” popular in many versions throughout East Asia, corvids come to the aid of lovers. The daughter of the King of Heaven, who wove the silk of clouds, had married a humble herdsman, and the two spent so much time together that they neglected their duties. The King finally placed the Weaving Maiden in the western sky and the herd boy in the eastern sky, where they were separated by the river of the Milky Way. One day every year, the crows and magpies gather and form a bridge across the sky so that the lovers may be briefly reunited.

In the Ghost Dance religion founded by the Paiute Indian shaman Wodvoka near the end of the nineteenth century, the crow was the messenger between the world of human beings and that of spirits. Indians from many tribes in the southwest of the United States, together with some whites, engaged in an ecstatic dance to bring about the regeneration of the earth. The celebrants wore crow feathers, painted crows upon their clothes, and sang to the crow as they danced. Sometimes they sang of Wodvoka himself flying about the world in the form of a crow and proclaiming his message.

In a volume of poetry entitled Crow, British poet Ted Hughes constructed a personal mythology. A figure named Crow continually does battle with cosmic powers; he may be defeated or victorious but always survives. But ravens and crows are not at all endangered. Corvids are found nearly everywhere in the Northern Hemisphere from remote cliffs and forests to cities. They neither fear man nor need him, and their resilience constantly inspires our respect.

OWL

Now the wasted brands do glow,

Whilst the screech-owl, screeching loud,

Puts the wretch, that lies in woe,

In remembrance of a shroud.

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Anybody who has come across the eyes of an owl shining alone in the night knows why they have always been associated with the dead. This is true especially in Northern regions where many owls are at least partially white; their feathers eerily reflect the moonlight. Not only does the owl look like an apparition, but its call is usually a drawn-out, wavering note that easily suggests the muffled voice of a spirit. Owls are attracted to places of burial by the smell of decaying flesh, and they could easily have been taken for the spirits of the deceased. These birds also have exceptionally fine sight at night. In total darkness, they can navigate by hearing or, with some species, even by echolocation. The ability of owls in flight to locate mice far below them, even under a coating of snow, still sometimes impresses researchers as almost supernatural. The ancient Egyptians represented part of the soul, called the “ba,” as a bird with a human head, and pictures of it in The Egyptian book of the Dead somewhat resemble an owl. In mythology and literature, death is intimately associated with wisdom, and the owl is an ancient symbol of both.

With most varieties of owls, the female is a bit larger than the male, which may partially explain why owls often symbolize primeval feminine power. In the Sumerian poem “The Huluppu Tree,” the goddess Lilith made her home in the hollow of a tree, but the hero Gilgamesh cut the tree down to make a throne for Inanna, the Queen of Heaven. Owls often nest in such places, and Lilith, who became a demon in Hebrew tradition, is referred to as a “screech owl” in the book of Isaiah. Babylonian reliefs from the early second millennium showed a goddess-demon, probably Lilith, with the claws and wings of an owl, sometimes with owls at her side. Ever since, owls have been the frequent companions of sorceresses and goddesses. Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom and war, is also closely associated with the owl. Homer refers to her as “owl eyed,” and the earliest depictions represent her as a woman with the head of an owl. She was later depicted holding an owl aloft in one hand. The Latin word for “owl,” “strix,” is the origin of “striga” or “witch.” In The Golden Ass by Lucius Apuleius, written in the first century CE Rome, a witch flies off at night in the form of an owl.

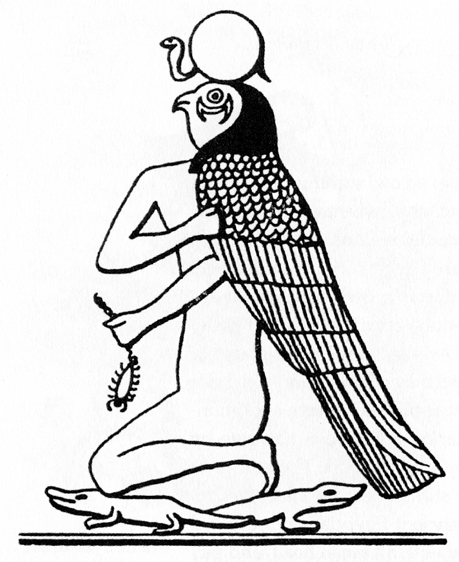

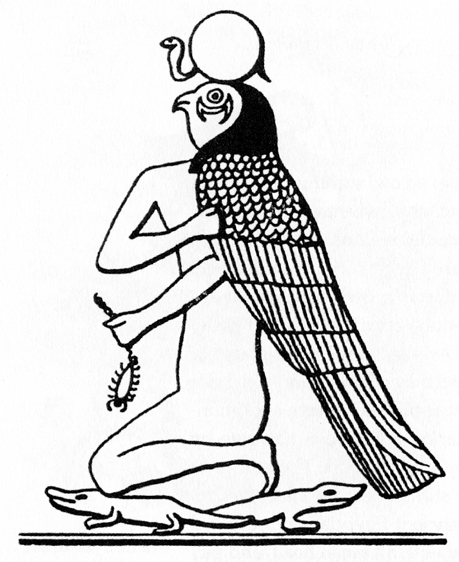

Sept, a Chtonic God of Egypt associated with the Owl.

The owl is a loner among the birds, a figure of both awe and revulsion. In one tale from the Hindu-Persian Panchatantra, the birds were so impressed by the owl’s venerable demeanor that they elected him king. During the day, when the owl was asleep, the crow mocked the choice, saying that the owl was repulsive with his hooked nose and huge eyes. The birds rescinded their decision, but an enmity between owl and crow remains to this day. This tale probably alludes to the way crows and other birds mob predators such as owls and usually succeed in driving them away.

In the Middle Ages the owl often represented the Jews, for, like them, the bird was said to have “scorned the light.” Writers of Antiquity including Pliny the Elder and Aelian had observed that other birds mobbed the owl when it appeared during the day. This idea was used later in Christian Europe as a justification for attacks on Jews who ventured beyond their ghetto.

For Odo of Chiteron, a clergyman writing in Kent during the early thirteenth century, the owl represented the rich and powerful who abuse their position. In his fable “The Rose and the Birds,” he recounts how the birds came upon a rose and decided that it should go to the most beautiful bird. They then debated whether this should be the dove, the parrot, or the peacock, but had come to no decision when they went to sleep. The owl stole the rose during the night, and so the other birds banished him from their presence; they still attack him if he shows himself by day. “And what will happen on judgment day?” Odo continued. “Doubtless all the angels … and just souls will—with screams and tortures—set upon such an owl.” It is a conclusion that anticipates the peasant’s revolts and other revolutionary movements that would start to become more common towards the end of the Middle Ages.

The aristocrats, who could be contemptuous of the masses, occasionally took the solitary nature of the owl as evidence of its superiority to other birds. A late 15th century shield from Hungary, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, shows an owl, perched above the coat of arms of a noble family, saying, “Though I am hated by all the birds, I nevertheless enjoy that.”

At the same time, the image of the various birds ganging up on the owl very clearly suggested the persecution of Christ. The full ambivalence that people felt towards the owl was expressed in an anonymous Middle English poem from the early twelfth century, entitled The Owl and the Nightingale, a heated debate on many subjects between the nocturnal bird of prey and the beloved songbird. The nightingale accused the owl of filthy habits, and the latter replied that she cleaned the churches and other buildings of mice. When the nightingale taunted the owl by saying that men used his dead body as a scarecrow, the owl replied that he was proud to be of service after death. (The image of the stuffed owl, however, suggests a crucifix, which was also a sort of scarecrow set up to keep demons away.) The owl boasted of being able to foresee the future and warn people of impending disaster. No judgment was rendered in the poem, but most readers think the owl got the better of his adversary. Medieval artists sometimes placed a cross above the head of an owl to indicate that it represented the Savior.

The idea that the cry of an owl foretells death is found in a remarkable range of cultures, from the Greeks and Romans to the Cherokee Indians. For the Navaho, the owl was a form taken by ghosts. For the Kiowa, it was a favored form of magicians after death. The Pueblo Indians would not enter a house where owl feathers or the body of an owl was displayed. For the Aztecs and Mayans, owls were the messengers of the god of death, Mictlantechtli. In the Aztec rites of human sacrifice, the heart of the victim was placed in a stone container decorated with an owl. Among several West African tribes such as the Yoruba, the owl is often a form taken by evil magicians, and simply to see or hear and owl can bring ill luck. For the Chinese, the great horned owl was the most powerful symbol of death.

In the modern period, however, life expectancy expanded dramatically, and people were no longer so constantly reminded of their mortality. In consequence, literature began to emphasize the reputation of the owl for wisdom rather than for death. Since the nineteenth century the “wise old owl” is probably most familiar as a figure in books for children. In the Disney film Bambi, an owl is even shown benevolently instructing baby rabbits and other creatures of the forest, which it would normally devour.

In J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter stories, wizards communicate by sending letters by owl. Harry, a budding young wizard who is learning magic at Hogwarts School, has an owl named Hedwig who keeps him company during lonely evenings. When not working as his messenger, she flies freely in and out of Harry’s room, sometimes bringing back dead mice, and affectionately nibbles on his ear.

Nevertheless, the fear that owls traditionally arouse has by no means vanished entirely. Occasionally in the late twentieth century, a proposal has been raised to control the population of rats in New York City by importing owls. This has never gotten very far, in part because the call and eyes of an owl during dark urban nights have proved too unsettling to people.

CARP AND SALMON

Now I am swimmer who dies,

Who runs with rain and moon and salt-wind tide,

River and falls and sweet pebble water.

Kwakiutl Indian tale, “Swimmer the Salmon” (adapted by Gerald Hausman)

Since very ancient times, people have thought of the sea as the womb from which all life emerges. Fish have symbolized the inexhaustible fertility of nature, and they have been closely associated with mother-goddesses such as Tiamat and Atargatis. Fishermen are the last hunter-gathers, and, even in antiquity, they were already surrounded by nostalgia and romance. The first disciples of Jesus were fishers, and Christ told them, “Follow me and I will make you fishers of men” (Matthew 4:19). The fish was the earliest symbol of Christ, and also the first avatar of the Hindu deity Vishnu. But despite their enormous importance in religion and other aspects of human culture, fish are remarkably difficult to humanize. The reason may be a combination of their remote, expressionless eyes and their utter silence, which contrast with the constant speech and expressive glances of human beings. Even in the animistic world of folklore, a talking fish is only rarely found, and when a fish does speak, it is usually in connection with some remarkable event.

The salmon, however, lives according to a remarkably “human” pattern. It is born in fresh water, migrates to the ocean and finally returns, sometimes swimming hundreds of miles upstream, to the place of its birth to spawn. Atlantic salmon may sometimes make the journey a few times during their lives, but Pacific salmon die after laying their eggs. In their determination to complete their destiny, salmon seem not only human but also very noble indeed. The entire life of a salmon may be understood as a sort of quest. It follows the mythic pattern described by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, where the archetypal hero, after many adventures, returns to end his life in the place of his birth. The way the salmon crosses the boundary between fresh water and the sea suggests a passage between the realm of men and immortals, and thus the salmon is a symbol of transcendence in many cultures.

Fish carved on reindeer antlers have been excavated in Paleolithic settlements of Spain and France, and a few of these fish are clearly recognizable as salmon. According to the Norse Eddas, Loki, the god of fire, assumed the form of a salmon in order to hide beneath a waterfall after he had offended the other deities with his taunts. But the salmon is most central in the cultures of the Celts and the Indians of North America.

The salmon of wisdom, which has superhuman knowledge, appears often in the myths and legends of the Celts. In the tale of “The Marriage of Culhwch and Olwen,” this is the salmon of Llyn Llyw, one of the oldest animals in the world. When King Arthur and his knights sought the hunter Mabon, they consulted this salmon, which not only told them where Mabon was imprisoned, but also ferried two men there upon its back.

According to one Irish legend, the old poet Finneagas once caught the salmon of wisdom and told the hero Finn MacCumhail to roast it for him. A blister arose on the salmon, and Finn pressed it, burning his thumb, which he placed in his mouth to ease the pain. Then Finn was suddenly filled with wisdom, which was apparent in his gestures and his gait. Finneagas had been expecting to gain this wisdom himself by eating the salmon, but he realized that destiny had granted it instead to his pupil, and so he was happy to have mentored Finn.

Several tales place five salmon of wisdom in Connla’s well, near Tipperary. Above the well were nine hazel trees, and their purple nuts would fall into the well to feed the salmon. The hazel nuts represented the spirit of poetry, and the sound of them striking the water was said to be lovelier than any human song. The bellies of the salmon were purple from the nuts, and their wisdom constantly increased. Only the salmon might eat the nuts safely, yet legend tells that the goddess Sinend was once so eager for wisdom that she defied the prohibition and approached the well too closely; the waters then rose and swallowed her.

A similar tale is told of a young girl named Liban in The Book of the Dun Cow, from the early Middle Ages. A well overflowed to form a lake, and Liban was swept to the bottom with her dog, but God protected them from the waters. The two stayed there for a year, until Liban saw a salmon and prayed, “O my Lord, I wish I were a salmon, so that I might swim with the others through the clear green sea!” In that moment, she became a salmon from the waist down, while her dog became an otter, and together they swam about for three hundred years. Finally, she allowed herself to be captured by some holy men and be taken to a cloister. She died immediately after being baptized and was consecrated as one of the holy virgins.

The return of a salmon to the place of its birth has suggested the coming of Christ, and the transition between Celtic religion and Christianity was probably eased by the shared symbolism of the fish. A similar significance was eventually accorded in Celtic areas to eels, which share with salmon the ability to move between pond and ocean. The salmon of knowledge could also be the ultimate origin of the wise fish in such popular fairy tales as Grimms’ “The Fisherman and his Wife” where it is a flounder, and Alexander Afanas’ev’s “Emilya and the Pike.”

The salmon also represents rebirth among Native American tribes of the Northwest Coast such as the Kawkiutl and Haida, not, however, as a unique event but as part of an eternal cycle. The salmon swimming upstream as it endeavors to elude predators such as bears signifies the individual bravely endeavoring to complete his or her destiny. Finally, after spawning, the dead salmon are swept back into the ocean, symbols of the ultimate union with all of life.

The carp is essentially a fresh-water fish, but it also swims upstream, sometimes leaping over falls in order to spawn, and Asian deities are often depicted riding upon carp. According to Chinese legend, the carp, on reaching its final destination, will become a dragon. In East Asia, the carp is a symbol of perseverance, and it is used especially to signify the scholar who studies hard to pass his examinations. The bright scales of a carp resemble armor, so the carp was often used as a symbol of samurai warriors. The Japanese have a national holiday in early spring known as “Children’s Day,” in which they fly carp-shaped kites, in order to inspire boys and girls to show persistence and courage.

To an extent, the carp shares the salmon’s reputation for mysterious wisdom. The first recorded versions of the enormously popular fairy tale “Cinderella” came in the early ninth century in China, and the helper of the young girl—the equivalent of the fairy godmother in the well-known version by Charles Perrault—is a fish. The young girl takes the fish home from a well, to be kept in a pond. Her wicked stepmother kills the fish out of spite, but the heroine prays to its bones, which grant her every wish. The kind of fish was not specified, but, since it was brightly colored and kept as a pet, it certainly appears to have been a carp.

Carp were introduced to Europe from East Asia in about the fifteenth century, and they have greatly extended their range throughout the world with the growth of trade. Salmon, by contrast, are now endangered everywhere, in part due to excessive fishing but mostly as a result of dam construction along their migratory routes. Varieties of salmon are produced for the market in hatcheries, artificially bred and even genetically engineered. These are sometimes inadvertently released into the wild, where they interbreed with wild salmon, often further endangering the original inhabitants of streams. In contact with human beings, it may be safer for animals to be beautiful than useful or wise.

HE PREHISTORIC CAVE PAINTINGS OF FRANCE AND SPAIN ARE AMONG the most ancient works of art that we have. The human beings in these paintings are usually crude stick figures that the artists do not seem to have considered very important. The animals are painted with far more care and passion. The first clearly identifiable religious shrines in history are at Çatal Huyuk in Anatolia and date from around the middle of the seventh millennium BCE. They were dedicated to animals, especially bulls, but also to vultures, foxes, and others. The Egyptians worshipped their gods as incarnated in cats, ibises, bulls, and many other creatures. Over millennia, anthropomorphic goddesses and gods slowly replaced the animal deities. The archaic divinities accompanied their more human successors, often as mascots or alternate forms. Athena, for example, was pictured with an owl, and Zeus with an eagle; Odin was accompanied by ravens and by wolves. The monkey Hanuman, who fought alongside the hero Rama in the epic Ramayana, is now perhaps the most popular figure in the Hindu pantheon. In folktales and fairy tales throughout the world, the human hero is often guided or advised by an animal companion. An aura of secret wisdom at times seems to embrace all animals, perhaps a legacy of these bestial deities. Their apparent lack of speech contains more wisdom than our incessant, and often futile, talk. The gaze of many animals, from insects to tigers, often seems more intent and confident than that of any human being. A very few animals, such as the raven or salmon have, however, an especially consistent reputation for wisdom.

HE PREHISTORIC CAVE PAINTINGS OF FRANCE AND SPAIN ARE AMONG the most ancient works of art that we have. The human beings in these paintings are usually crude stick figures that the artists do not seem to have considered very important. The animals are painted with far more care and passion. The first clearly identifiable religious shrines in history are at Çatal Huyuk in Anatolia and date from around the middle of the seventh millennium BCE. They were dedicated to animals, especially bulls, but also to vultures, foxes, and others. The Egyptians worshipped their gods as incarnated in cats, ibises, bulls, and many other creatures. Over millennia, anthropomorphic goddesses and gods slowly replaced the animal deities. The archaic divinities accompanied their more human successors, often as mascots or alternate forms. Athena, for example, was pictured with an owl, and Zeus with an eagle; Odin was accompanied by ravens and by wolves. The monkey Hanuman, who fought alongside the hero Rama in the epic Ramayana, is now perhaps the most popular figure in the Hindu pantheon. In folktales and fairy tales throughout the world, the human hero is often guided or advised by an animal companion. An aura of secret wisdom at times seems to embrace all animals, perhaps a legacy of these bestial deities. Their apparent lack of speech contains more wisdom than our incessant, and often futile, talk. The gaze of many animals, from insects to tigers, often seems more intent and confident than that of any human being. A very few animals, such as the raven or salmon have, however, an especially consistent reputation for wisdom.