In the lobby of the Chief Medical Examiner’s office in New York City, there is a phrase in Latin, on the main wall behind the security desk:

Taceant colloquia. Effugiat risus.

Hic locus est ubi mors gaudet succurrere vitae.

The phrase is best translated as “Let conversation cease. Let laughter flee. This is the place where the dead come to aid the living.” The Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in New York City is where autopsies are performed to investigate deaths that occur within the city. Most major cities have a building like this one, or use city hospitals to house the forensic death investigation services. Regardless of where the facility is located, the phrase above is an important one, and clearly states the purpose of the building and the work that goes on inside it. The primary mission of the medical examiner (ME) is to investigate cases of persons who die from criminal violence; by casualty or by suicide; suddenly, when in apparent good health; when unattended by a physician; in a correctional facility; or in any suspicious or unusual manner.

Forensic pathology is the medical and legal process of investigating the cause and manner of death. Pathology, in normal medical terms, is the science of disease and dysfunction. If you have a biopsy done on a possible tumor, the sample is sent to the pathology department in the hospital, where the doctors perform tests to see if it is benign (not harmful) or malignant (a rapid-growth tumor). In forensic science, pathology still deals with disease and dysfunction, but usually only in the process of investigating a death.

Forensic pathology has several aspects that play a role in the investigation process. First and foremost is the autopsy, a process in which the body is examined externally and internally by a forensic pathologist to find the cause and manner of death. During an autopsy, samples of internal organs, body fluids, and foreign objects may be recovered by the forensic pathologist, and these are usually sent to other labs within the ME’s office for further testing. If, for example, a disease is suspected, the tissue samples can be sent for histological testing.

Histology is the science of cells and tissues. A histology lab prepares a tissue sample on a microscope slide and “stains” the tissue to highlight certain diseases, abnormalities, or functions of a cell that can give a forensic pathologist clues to how somebody died.

Likewise, body fluids and other foreign objects can be sent for toxicological testing. Toxicology is the science of toxins and poisons. A toxicology lab can screen body fluids and tissue samples for drugs, toxins, or poisons. If there are drugs, toxins, or poisons present, the toxicology lab can determine how much of the substance is present in the body, and if it was in fact at lethal levels. All of this information serves to aid the forensic pathologist in his or her job of answering the questions surrounding a suspicious death, discussed next.

These are the basic questions of any investigation of a suspicious death. The forensic pathologist’s job is not to answer these questions themselves. The true job of the forensic pathologist is to interpret what the body reveals, and to be a voice for the dead!

Identification is a major issue in any forensic investigation, and this is true as well in forensic pathology. Identification can be done in several different ways. A body may be visually identified by a relative or loved one, or can be accomplished simply by checking the photo ID that is found on the deceased. Sometimes the identification cannot be done based on facial recognition; scars, marks, tattoos, or piercings that are unique to the individual must be used instead.

Many times, a body is found without ID or is so badly decomposed that it cannot be recognized at all. In such an instance, ante-mortem (prior to death) dental records, when compared by a forensic odontologist to the post-mortem (after death) dental x-rays of the unknown body, can help make an identification. The use of ante-mortem x-rays can also highlight old broken bones, surgical implants, or old wounds, and can be matched against corresponding bones, implants, or wounds on an unknown body. There even have been instances in which unknown bodies have been identified by matching the serial numbers found on artificial hips, breast implants, and pacemakers to medical records of the deceased owners.

If none of these methods produces an identification of an unknown individual, a forensic pathologist might then rely on fingerprinting or DNA analysis to help provide a name. The importance of identification of the body is not only to establish the name and identity of the deceased, but also to be able to notify the family of the deceased so that they will have the opportunity to oversee the internment of the remains.

When a forensic pathologist begins investigating a death, there is one main question specifically about the death that must be addressed: what was the manner of death? The manner of death can be only one of five possibilities—homicide, suicide, natural, accidental, or unknown. It is up to the forensic pathologist to take into account all of the information surrounding the case, including the findings from the autopsy, reports from histology and toxicology, and even aspects from the police investigation and crime scene details, to make a final decision on the manner of death.

The manner of death is the most important finding in a death investigation case, and can be made only by the forensic pathologist. For example, if there is a body found at a crime scene and the police have a suspect in custody, if the manner of death is found to be a homicide, then the suspect can be formally charged with the victim’s death. But, on the other hand, if the forensic pathologist finds that the victim died from natural causes or was a suicide, then the suspect is set free. The only problem with establishing the manner of death is the fact that one of the categories is “unknown.” A forensic pathologist may opt to report this finding if the evidence from the autopsy, reports, and other information does not clearly answer how a person died, or if there is an equal possibility of more than one manner of death.

The time of death is an important fact that a forensic pathologist must determine in the course of a death investigation. Sometimes, the time of death is clearly known, perhaps by people at the scene of the death, or by medical personnel that were unable to save the person’s life. However, if a body is discovered without any clear way to identify the time of death, the forensic pathologist has several avenues of investigation to approximate when the person died.

The first thing a forensic pathologist looks at when determining the time of death is the stiffening of the body, which is known as rigor mortis. Rigor mortis is a process in which the muscles of the body contract, because after death there is no chemical energy for muscles to use. As the body begins to decompose, the muscle tissue begins releasing enzymes that break the muscle tissue down and cause it to lose the stiffness. The time in which this happens is fairly constant and predictable, and if a body is kept under careful observation, the stiffening/relaxing of the body can point back to the original time of death.

Rigor mortis usually starts to set in 12 hours after death, at which point it begins to slowly stiffen the outermost extremities of the body, the fingers and toes. Over the next 12 hours, the entire body becomes completely rigid, so that 24 hours after death, the body is rock hard and the arms, legs, and head can be moved only with great difficulty. After the body is in full rigor, it takes another 12 hours for the muscles to relax and the body to return to a limp state. So, if a body is found within the first 36 hours after death, a careful analysis and observation of the rigor can be back-calculated to an approximate time of death. For example, if a body is found in partial rigor (the fingers and toes are immobile and the arms and legs are stiff), and under observation full rigor sets in 4 hours later, and another 12 hours later the body is limp, it can be estimated that the body was found approximately 20 hours after death.

Another important indicator that a forensic pathologist can use to determine the amount of time since death is the body’s temperature, or algor mortis. Algor mortis is the constant rate at which a dead body loses heat, and in a normal, room-temperature environment is about 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit every hour. Because the average body temperature is 98.6 degrees, the forensic pathologist can use a thermometer to measure the rectal or internal liver temperature of a body. If, for example, the internal temperature of a body is around 95.5 degrees, and the body was found in a normal room, the algor mortis determination shows the time of death to be 2 hours ago (98.5 – 95.5 = 3 degrees; if the body loses 1.5 degrees every hour, then it takes 2 hours to lose 3 degrees). Algor mortis can be tricky, though, because the ambient temperature can speed up or slow down the rate at which a body cools. Therefore, a body found in a freezing meat locker or kept outside on a hot July day will not accurately reflect the real algor mortis rate. A forensic pathologist must take the environmental conditions into account when looking at the body’s temperature.

While rigor mortis and algor mortis are helpful indicators for a forensic pathologist, they are only useful within the first two days after death. If a body is found a week or even a month after death, neither rigor nor algor mortis will be useful for the forensic pathologist. Another discipline that can be used to determine the time since death has nothing to do with what’s in the body, but rather what’s on it. That means maggots, flies, and beetles! Insects have an amazing ability to find dead bodies, and the life cycles of several insects are well known and specific. A forensic pathologist might seek out the expertise of a forensic entomologist, also known as a forensic insect expert, to identify the species of insect and to determine the length of its gestational cycle. This can help in giving a better idea of the number of days since death. While insect activity is not as good as rigor mortis or algor mortis in determining the time of death to the hour, it can help in estimating the number of days or weeks since death.

The scene of death is important. It might contain further evidence that can be used in determining the manner of death. As a result, bodies are sometimes moved by the perpetrator to cover up the original, or primary, crime scene. The forensic pathologist, though, can look at key physical characteristics on the body to help show whether or not the body was moved, and if so, where the original scene of death might be.

When a person dies, the heart stops pumping blood throughout the body. As the body’s cells begin to break down, the capillaries around these cells burst, causing blood to pool in the tissues of the body. Blood, like all liquid, settles to the lowest spot because of gravity. If a person dies on their back, their blood pools in the backs of their legs, buttocks, shoulders, arms, and head. As the blood pools in these areas, it can be seen through the layers of skin as red splotches. This is known as livor mortis. These splotches begin to form immediately after death, and after a certain amount of time become permanent, or fixed. While this can aid a forensic pathologist in determining the time since death (see the previous section), it is most useful in showing that a body was in the same position when the person died. For example, if a person died on his back and livor mortis set in, and then the body was moved and placed face down, the livor mortis would still show up on the back of the arms, legs, shoulders, head, and buttocks. This would prove that the body was moved post mortem. Moreover, livor mortis cannot occur where the tissues are being squeezed or pressed. For example, if a person died sitting in a chair, the blood cannot easily pool in the back of the legs or on the buttocks because the weight of the person is compressing those tissues. Livor mortis would be present on the lower back and on the feet as well. If the body was moved from the chair after the livor was fixed, the backs of the thighs would show blanched areas where no blood had pooled while the surrounding tissues would be a deep red.

While livor mortis can help show that a body was moved, it does little to help locate the original crime scene. To do this, a forensic pathologist must carefully collect the trace evidence from the body and rely on trace evidence experts to analyze whatever was found on the body. It is therefore important that forensic pathologists be well skilled in all aspects of forensics, not just pathology, so that they can find all of the evidence that the body has to reveal.

The question of “why” is just as important as the question of “what” in a death investigation. The “what killed this person?” question led to the manner of death, but the question of “why did this person die?” deals with the mode, or cause of death. The mode of death is what led to the manner of death, and can be any number of reasons. For example, the mode of death in a homicide could be anything from a shooting to a stabbing to a poisoning, or a combination of all three. If you think about it, though, these same modes could also be the reasons for a suicide or an accidental death.

Sometimes, the actions that lead to a death can be the same from case to case, but the effects of the actions result in different modes of death. For example, in a homicide, a shooting might have ruptured a lung, leaking air into the chest cavity and causing the lung to collapse and the person to ultimately suffocate. (This is known medically as a pneumothorax.) Therefore, the autopsy report would indicate that a shooting (mode 1) led to a pneumothorax (mode 2), which led to suffocation (mode 3), which resulted in a homicide (the manner of death). Alternatively, sometimes a shooting is not instantly fatal, but the projectile is retained in the body. If the bullet later dislodges, it can work its way into the circulatory system and get lodged in the brain or the lungs, cutting off the blood supply to these organs, causing death. This could be months to years after the shooting, but since the bullet from the shooting (mode 1) led to the fatal blockage (mode 2), which led to the death of the person, the death is still ruled a homicide (the manner of death). Determining the mode of death is therefore the second factor in death investigation that is the singular responsibility of the forensic pathologist. Although the facts of the investigation are gathered by all of the investigators involved in the case, the forensic pathologist ultimately has the responsibility to issue the final death certificate that outlines the mode and manner death.

Up to this point, the focus of the forensic pathology discussion has been on the forensic pathologist, but other people may be involved in a death investigation. Sometimes, the local laws and ordinances dictate what type of death investigator is in charge of a case. In some states and counties, the medical examiner (ME), a medical doctor who works at the medical examiner’s office, is given the authority. In other areas, a coroner is employed as the lead death investigator. Whereas an ME is always a medical doctor, a coroner needs only basic training in determining whether a body is dead, and issues reports based on the autopsy, toxicology findings, etc. that are performed by other specialists. Coroners are also typically elected positions in local or state governments, whereas an ME is an appointed physician outside of the political arena. Although a coroner could be a medical doctor, they typically are not, and therefore rely on a doctor or pathologist for the autopsy report.

Another major difference between a coroner and an ME is that the coroner typically responds to the scene of death or goes to where the body is discovered. An ME might go to scenes, but in specific areas around the United States, medical examiner systems rely on medicolegal investigators (MLIs) to attend the crime scenes, collect evidence, and pronounce the body dead. An MLI typically has a degree from a physician’s assistant program, and a strong background in forensics. Using such a system, the MLIs attend to the scene of death, allowing the MEs to devote their time to performing autopsies and reviewing the histology and toxicology results. In the end, this allows the city or county that utilizes such a system to investigate a higher number of cases, which is beneficial for the society that is served by the death investigators.

When a body arrives at a morgue, hospital, or ME’s office for an autopsy, there are several things that should already be known about the body. These are the facts from the scene of death or where the body was found, and should include the condition of the body, the sex of the person (if it can be determined), the ambient temperature and the environmental conditions surrounding the body, and a detailed account of the debris, personal effects, or other possible evidence surrounding the body. If a homicide or a struggle is suspected, the hands of the body should be covered in clean paper bags and sealed with ties to prevent any trace evidence from getting dislodged and lost in the body bag. If the body is coming from a prison or hospital, all of the medical devices or personal effects should remain attached to the body so that the forensic pathologist can determine if the presence of the items led to the death of the person.

As bodies arrive at the morgue, they are usually kept in large refrigerated rooms or coolers to slow down the decomposition process. Just before the autopsy, the body is undressed, weighed, and measured. If necessary, the body is x-rayed and photographed, both to document the condition of the body and for identification purposes.

During the autopsy, several people may be present in the autopsy suite. These include the forensic pathologist, who performs the majority of the autopsy, and possibly other pathologists who are present to observe the autopsy or aid the lead pathologist as prosectors (pathologists who dissect the internal organs, looking for signs of disease). Another person who is commonly present is a mortuary technician, whose job is to prepare the body for autopsy by washing it after the external examination, and to assist the pathologist throughout the course of the autopsy with moving, turning, and repositioning the body. At the end of the autopsy, the mortuary technician replaces the removed organs and sews the body up for removal to a funeral home or city cemetery. Additional people who might be present at the autopsy are the police detectives or district attorneys if the case is a suspected homicide, as well as a forensic photographer who is present to document signs of trauma or abnormal findings, or just to record the process of the autopsy.

When the autopsy begins, the body is transferred from the body bag to the autopsy table. This may be a normal, operating room–style table, or it may be a specialized table that includes drains and running water to help siphon off the fluids from the body. Surrounding this table are the various implements that the forensic pathologist uses to examine the body. First and foremost, the forensic pathologist must have a way to document all the findings during the autopsy, whether this is with pen and paper, a wax pencil and a dry-erase board, or a wireless voice-activated dictation recording device. Whatever the medium, all of the information gathered in the course of the autopsy must be recorded, from the weight of the internal organs to unusual smells that the forensic pathologist might encounter during the procedure. Other implements in the autopsy suite include a scale to weigh the organs, a cutting board for dissection of the organs, jars and buckets for tissue samples, and a variety of scalpels, knives, hooks, syringes, and other medical implements designed to enable the forensic pathologist to find out the body’s answers to the who, what, when, where, and why questions surrounding that person’s death.

After the body is placed on the autopsy table, the first step in the procedure is the external examination. This is done by the forensic pathologist to look for any outward signs of trauma or unusual features, as well as to look for any outward signs of disease and to get an idea of the general health of the person at the time they died. Also at this time, trace evidence that is on the outside of the body can be identified and collected, including tape lifts from the skin, pubic hair and head hair combings, and, where applicable, scrapings from under the fingernails to see if any of the attacker’s skin or other telltale debris might be present. If a sexual assault is suspected to have occurred in the course of the victim’s death, a post-mortem sexual assault evidence kit is used to collect possible semen or saliva evidence from the vagina or penis, anus, mouth, or even the skin of the victim. All of this trace evidence is collected and sealed to be sent to other laboratories for testing. If the body is dirty or covered in debris, it is then washed and re-examined to see if any more information is available on the surface of the body. Once all of the external evidence is collected and documented, the pathologist is ready to begin with the internal examination of the person.

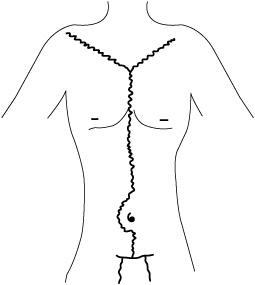

To begin the internal examination, the forensic pathologist performs a Y incision, which consists of cutting the skin on the chest from shoulder to shoulder across the collarbones, and then cutting from the top of the breastbone to just above the pubic region, which results in a large “Y” carved into the body (see Figure 5-1).

Figure 5-1 Y incision

The skin is then pulled back to expose the internal organs and the ribcage. The breastplate must be removed so that the pathologist can access the heart and lungs, so the ribs are cut using a saw or a device that looks like (and sometimes is!) a tree pruner. Once the breastplate is removed, the forensic pathologist performs a quick overview to make sure that all of the organs are in the proper position and looks for obvious signs of disease (see Figure 5-2). If the death is a violent crime like a stabbing or shooting, the first examination to be done is to find the path of the blade or the bullet in order to see what internal organ was damaged, and if that damage is indeed the primary cause of death.

Figure 5-2 Internal layout of organs

After the chest and abdomen are opened and the overview examination is complete, the forensic pathologist begins removing the various internal organs, weighing each one, and dissecting each looking for flaws or signs of disease. For example, when the heart is removed it is weighed. If it is within a certain weight range for the age, height, and body weight of the individual, then the heart is considered normal. If the heart is too large, it could be a sign of heart disease, hypertension, or other coronary factors that led to the death. As the heart is dissected by the pathologist or one of the prosectors, the valves are checked for disorder and the coronary arteries are checked for blockages and other signs of heart disease. The same is done with the other organs as well, including the liver, lungs, kidneys, spleen, gallbladder, and stomach. The stomach is unique, in that the contents can be recovered and saved as well. The stomach contents are useful not only as evidence, but sometimes also to help establish the time of death based on known rates of digestion of certain foods. In cases of drug overdose, the stomach contents can also help identify what kind of drug the decedent ingested based on partially digested capsules or tablets. Finally, the intestines and bladder are removed and drained to check for signs of disease and problems. While this is being done, each of the major organs are sectioned and sampled for histology and toxicology. As the organs are dissected, a small piece of each organ is cut off and placed in a jar with a preservative chemical, usually formalin or formaldehyde. Once all of the major organs have been removed and checked, they are placed in a plastic bag and the bag is returned to the chest cavity, along with the breastplate.

At this point, the major examination on the body is complete, but the forensic pathologist might need to do further dissection on other areas of the body. For instance, if evidence suggests the body was hit by a vehicle, the forensic pathologist may need to dissect the knees and legs to look for signs of fracture or ruptured blood vessels. In another instance, if strangulation or suffocation is suspected, the forensic pathologist may need to dissect the neck to check for damage to the windpipe or hyoid bone (a broken hyoid bone is a strong indicator that the person was strangled). If carbon monoxide poisoning is suspected, the vitreous fluid (the liquid inside the eyeball) can be removed and sent to toxicology. Once all of these secondary examinations are complete, it is time to move on to the head and brain.

To remove the brain, the forensic pathologist or mortuary technician begins by making an incision from ear to ear on the back of the head. This allows the scalp to be pulled forward to expose the skull (see Figure 5-3). This is done mainly to leave the face and forehead intact in case the body will be viewed at a funeral. Seeing this procedure done is by far one of the most unnerving aspects of the autopsy, because the skin is pushed forward as the scalp is reflected, causing it to look like a rubber mask drooping off of the face.

Figure 5-3 Rear view of reflected scalp

Once the skull is exposed, a special bone saw called a Stryker saw is used to cut the skullcap. This saw is a special vibrating saw that cuts only hard objects. Because it’s not a spinning saw, it will not damage soft tissue. Once the skull is cut, it is pried off using a tool like a crowbar, exposing the brain. The brain is covered by a thin membrane called the meninges (the disease in which this membrane becomes infected and inflamed, causing pressure on the brain, is meningitis), and this is examined and cut open to expose the brain tissue. The brain is partially removed from the skull, and the forensic pathologist then must cut the spinal column to separate the brain from the brain stem, after which the brain is removed from the head. Unfortunately, the brain cannot be immediately dissected at this point. The brain is made of extremely soft tissue, the consistency of which is like runny Jell-O. Because of this, the brain cannot be immediately sliced. After the brain is removed from the body, it is placed in a bucket of formalin for two weeks. Much in the same way boiling water firms up a runny egg, the chemicals firm up the brain tissue, allowing it to be easily sliced and dissected for histology, toxicology, and neuropathology (the study of the diseases of the brain and nervous system). After the brain is removed from the body, the skullcap is replaced and the scalp is moved back to its original position.

To finalize the autopsy, the incision on the back of the head and the Y incision are stitched up by the mortuary technician, and all of the vital information is transcribed on the death certificate. The body will typically be wrapped in a sterile sheet or be replaced in a body bag if there is no further need for the body, and then sent to a funeral home. The tissue samples are sent to toxicology and histology, and the forensic pathologist awaits the results from those labs while beginning to write up the autopsy notes in a case file. Along with the autopsy information, the file will contain photos from the autopsy, x-rays, documents about the personal effects found on the body, and, if the body was identified by a family member or loved one, a letter of identification. While the mode and manner of death might be known after the autopsy, all of the results from the other labs must be checked to confirm this finding. If after the autopsy the mode and/or manner of death is still unclear, the forensic pathologist must rely on the lab tests to aid in a final diagnosis of the cause of death.

As the preceding discussion of the autopsy illustrates, even a simple autopsy takes time and is a complicated procedure, requiring the work of several specialists to uncover the ultimate cause of death. In more complex cases, where there is a violent crime such as a shooting, stabbing, or beating that led to the death, the discovery and documentation of the wounds is critical to the case. Documentation of the wounds not only proves the cause of death, but must also be presented in a court of law as evidence of the criminal act of homicide. There are several different types of wound patterns that a forensic pathologist might encounter in the autopsy of a violent death.

Defensive wounds are typically found on victims who were killed in close proximity to their attacker. If the attacker was wielding a weapon, such as a knife, the defensive wounds usually are found on the hands and forearms of the victim. Because weapons like blades, clubs, and axes require the attacker to be in close proximity to the victim, there might be a hand-to-hand struggle. If this happens, the victim, while attempting to defend themselves, will be injured by the weapon. In a knife attack, it is common to see defensive wounds on the hands or forearms in the form of deep lacerations in the skin. With a club or another type of crushing weapon, the bones of the hands or forearms might be broken or bruised as a result of the struggle. These wounds, when present, indicate a violent struggle and can aid the pathologist in understanding the method and weapon used in the attack. The presence of such wounds also can indicate that the death was not suicide or accidental if the manner of death is not immediately clear.

When a person is stabbed with a sharp object, the wound is known as a puncture wound. This wound type can occur with anything from a syringe needle to an ice pick to a blade. Each of these weapons produces a different size puncture wound, which penetrates the body at different depths and causes different injuries. Commonly, the injury from a needle is not lethal but the contents of the syringe might be toxic or poisonous to the individual being stuck. An ice pick or a blade, on the other hand, can penetrate deeper into the body and rupture internal organs or blood vessels, leading to death. During an autopsy, the forensic pathologist must look for these wounds and trace the path of such punctures through the body’s layers and organs. Sometimes, a person might be stabbed multiple times in an attack, but only one of the punctures is lethal. All of the injuries must be documented and investigated so that the forensic pathologist can uncover the fatal wound.

A laceration is a cut or a slice in the skin, usually made by a blade or a sharp object that is swung or sliced. Compared to a puncture wound, a laceration is wider but not as deep, but can still produce fatal results if major blood vessels are severed in the injury. Laceration wounds usually have smooth edges, depending on the type of weapon or the speed at which the weapon is moving when it contacts the skin. In close-contact knife attacks in which the victim has defense wounds, these wounds are commonly lacerations on the hands and forearms.

Abrasions cover a wide variety of injuries that can occur on the surface or under the surface of the skin. Abrasions can be found in injuries like bruises and scrapes, to entire regions of skin worn away by friction. The term “road rash” is commonly used to describe the effect on the skin of a person involved in a vehicular accident when sliding across pavement. Contusions are injuries that extend deeper into the body, and are commonly the result of blunt force trauma, which happens when a body is beaten or otherwise subjected to hard, sudden impacting forces. While abrasions and contusions may or may not be fatal, the discovery of these injuries can provide important clues to the nature of the death, and can therefore aid the forensic pathologist in making a final determination as to the manner of death. For example, a body that has no serious outward injuries such as punctures or lacerations might be heavily bruised instead. Such bruising could lead the forensic pathologist to look for a fatal blood clot that could have traveled to the heart, lungs, or brain and led to the death of the individual.

Tearing is a more general term used to describe wounds caused by shearing forces. When the body is subjected to shearing forces, the skin and tissues shred, producing rough, ragged edges and typically large blood loss. These wounds can result from mechanical injuries, but are also seen in violent animal attacks. While lacerations and abrasions tend to affect only the skin and rarely affect the underlying tissues, tears tend to shred all of the underlying muscles, as well as the bones and connective tissues.

Gunshot wounds are seen in several different manners of death, from homicides to suicides to accidents. A bullet does damage to a body mainly in two ways:

• The bullet penetrates the body, puncturing the skin and underlying organs, causing rupturing of such organs and blood vessels.

• The kinetic energy of the bullet is transferred to the penetrated skin and organs, causing tears and other expanding-force trauma. Imagine that the kinetic energy is like a balloon that is inserted uninflated into the body. As the balloon is inflated and expands, the edges of the balloon push organs and skin out of their natural positions, causing the organs and skin to rip and tear to allow for the expanding balloon. This type of energy-transfer damage is usually seen only in wounds produced by high-powered rifle rounds or large-caliber pistol rounds.

Because shooting deaths may include more than one wound in the body, it is the responsibility of the forensic pathologist to trace the route of every bullet through the body, and attempt to recover the round if is still present in the body, for comparative-testing purposes.

Another important aspect of gunshot wounds is the distance of the body from the weapon. The closer the victim is to the gun, the more likely two types of gunshot wounds will be present. The first type includes the presence of punctuate abrasions on the skin surrounding the gunshot wound. These wounds are known as stippling. Stippling is produced by unburned or still-burning gunpowder moving at high velocity as it ejects out of the barrel following the bullet. The closer the person is to the weapon, the tighter and more pronounced the stippling is on the skin. For the forensic pathologist, the presence of stippling is a sign that the gunshot was a close-contact shot, and can establish how far away the shooter was from the victim.

The second type of gunshot wound that can help establish the distance of the weapon from the body results from the expansion of gases that follow the bullet out of the barrel (along with the gunpowder). When a bullet is fired, a chemical reaction of the gunpowder causes the powder to ignite and rapidly burn, producing rapidly expanding gases that propel the bullet from behind and push the bullet down the barrel of the gun. These gases follow the bullet out of the barrel, but quickly dissipate into the atmosphere after a few feet. However, if a body is close enough to a gun while these gases are rushing out of the barrel, the gases can enter the wound following the bullet, further expanding the skin and organs. This gas causes not only ripping and expansion-type injuries, but thermal injuries as well due to the heat produced in the burning of the gunpowder. Again, for a forensic pathologist, the presence of such burned, expansion-type wounds surrounding a gunshot can also help establish how close the victim was to the weapon when it was fired.

If a body is left undiscovered for a long time, when it is finally discovered, the soft tissue and organs may no longer be present. All that remains is the skeleton of the person. In such cases, a normal autopsy is impossible, because clues as to how the person died that would normally be found in wounds in the skin or diseases in the organs have long since vanished. As a result, the forensic pathologist might turn to a forensic anthropologist to examine the bones and attempt to answer the questions of who, what, when, where, and why. Forensic anthropology is the study of bones and skeletal remains, which is quite different from the classical view of anthropology, which is a social science that studies the culture of large groups or societies. Forensic anthropology has nothing to do with the study of culture or society, and instead focuses on using the bones or other remains of a person to estimate the age, weight, sex, height, race, and even the manner of death. Forensic anthropology is capable of doing this based on key features and differences that can be seen in the bones from one person to another. For example, to establish the sex of a person, the forensic anthropologist might examine only the pelvis. On a male, the pelvis tends to be narrow and flat, whereas in a female the pelvis is wider and more bowl-shaped. These differences are based on the physical uses of the pelvis by the different sexes, and are clear indicators to a forensic anthropologist of the sex of the unknown individual. Other vital information that the forensic anthropologist can find from the bones is the age, weight, height, and race of the person, all by comparing known standards to measurements from the skeletal remains.

Beyond the physical attributes of the body, the bones can also tell the forensic anthropologist how the person died. In violent deaths, bones may be nicked or cut with knives, blades, or axes. Bones may be shattered or crushed by blunt-force trauma from a beating or high-speed collision. Bones may even show the path of a bullet through the body if the bones were hit by the projectile. Bones can even trap bullets, and there has been more than one case of a bullet found embedded in a rib or skull that could be traced back to the original weapon.

Ultimately, bones can be used to identify a missing individual by comparing dental records or known x-rays to the unknown skeletal remains. The condition of the bones can even provide clues to a forensic anthropologist about how long the person has been dead. While time-of-death estimates based on skeletal remains are not accurate down to the minute, a forensic anthropologist can usually narrow down from years to months the time since death based on the overall condition of the bones. Although bones do not offer the same evidence that a whole body offers for a death investigation, they still can provide clues to the forensic anthropologist and pathologist to help them solve the case.

In recent years, there have been several notable mass disasters that have claimed numerous human lives, such as the flooding of New Orleans in 2006 after Hurricane Katrina, the tsunami disaster in the Indian Ocean in 2005, and the attack on and collapse of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. Various other situations, from plane crashes to destructive earthquakes, can also cause a large number of dead that need to be recovered and examined by a forensic pathologist. When a mass disaster occurs, the death toll could be several hundred to several thousand lost lives, with each of those bodies requiring identification and a ruling on the mode and manner of death.

The challenge of forensic pathology when faced with a mass disaster is the fact that every one of the victims in the disaster requires an investigation into their death. In an earthquake or plane crash, the resulting deaths are usually ruled as accidental. In the World Trade Center disaster, however, the attack was a terrorist act. Therefore, the dead in the World Trade Center disaster were all ruled as homicide victims.

Because the manner of death for the World Trade Center victims was established as a homicide, it made the recovery and examination of the bodies that much more important. As part of the investigation of the bodies, it was determined that the mode of death for most, if not all, of the victims of the World Trade Center was blunt force trauma. This finding was based on the direct examination of the victims’ remains. Because of the nature of collapsing buildings, the crushing and tearing forces that took the victims’ lives made any further examinations or findings impossible. Once the mode and manner of the deaths were established by the forensic pathologists, the second, and most important, aspect of the investigation began—the identification process.

Identifying the dead is always a goal in a forensic pathology examination. For intact bodies, the issue of identification in a disaster recovery effort is usually done by searching the body for ID, or using fingerprints or dental records to find the name of the individual. In the case of the World Trade Center disaster, there were other factors that unfortunately left the bodies shredded, burnt, and in many cases indistinguishable as human. The identification of body parts, then, became a two-prong approach to the recovery effort. The first step was to identify the body part as belonging to an individual, either through anthropology, odontology, fingerprinting analysis, or DNA. The second step was to match all of the pieces of the bodies back together, again using the same technologies, so that the families could bury all of the remains of their deceased. Because of the scale and scope of the World Trade Center disaster, there were many bodies and body parts that were not identified, and many families left without the closure of being able to bury their loved ones.

In the end, out of the 2749 victims of the World Trade Center attack, the recovery effort was able to identify 1592 of the bodies. Out of those victims, every body, and every body part, was examined by a forensic pathologist and tested to the full extent of what forensic technology would allow, helping bring closure to one of the largest attacks on U.S. soil.

Refer to the text in this chapter if necessary. Answers are located in the back of the book.

1. A deceased body at a crime scene is found in full rigor. Under observation, the extremities begin to become flexible after 3½ hours. What is the probable time of death?

(a) The week before the body was found

(b) The day before the body was found

(c) Approximately 20 hours before the body was found

(d) Approximately 8 hours before the body was found

2. Vitreous humor is found in:

(a) The brain

(b) The liver

(c) The gallbladder

(d) The eye

3. What body fluid is preferred for carbon monoxide testing?

(a) Urine

(b) Cerebral-spinal fluid

(c) Vitreous fluid

(d) Semen

4. The settling of the blood in the body due to gravity is known as:

(a) Rigor mortis

(b) Algor mortis

(c) Livor mortis

(d) Vitreous humor

5. Entomology is the study of:

(a) Fingerprints

(b) Hair

(c) Trace evidence

(d) Insects

6. The mode of death is also known as:

(a) The manner of death

(b) The method of death

(c) The cause of death

(d) The side of death

7. The decrease of body temperature over time after death is known as:

(a) Rigor mortis

(b) Algor mortis

(c) Livor mortis

(d) Vitreous humor

8. The cutting made into the torso of a body during an autopsy is known as a:

(a) X incision

(b) Y incision

(c) Z incision

(d) Prosector

9. A shallow, wide wound with smooth edges might be best classified as a:

(a) Tear

(b) Abrasion

(c) Laceration

(d) Puncture

10. The sex of a skeleton can be most easily determined with which bone?

(a) Phalange

(b) Humerous

(c) Rib

(d) Pelvis