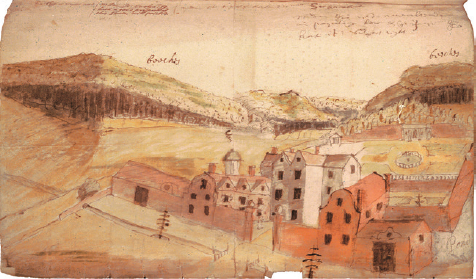

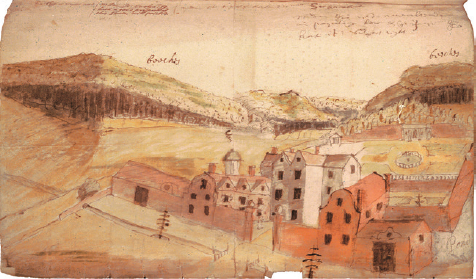

WHEN EVELYN CAME to write up his Diary in 1660,1 he began by noting the domestic situation into which he was born in 1620, recording the ages and characters of his father and mother: his father ‘low of stature, but very strong . . . exact and temperate’ (Diary, II.2), his mother ‘of proper personage, well timber’d, of a brown complexion . . . inclin’d to a religious Melancholy, or pious sadness; of a rare memory, and most exemplary life’ (II.4–5). He also acknowledged the house and estate of Wotton, in Surrey, 22 miles from London, which had become the family home in 1579, and which Evelyn’s father, Richard, inherited in 1595 (illus. 5).

Wotton would be at the centre of Evelyn’s life, if not physically, at least as the lodestone or compass that guided his life, until, by accident, he actually inherited it in 1699, when his brother died without any heirs. It was not the still point of the turning world, for the world was changing rapidly in many ways, and Evelyn would both encourage and lament the results. But Wotton would be – in the words of John Donne – the fixed foot of the compass that directs its other, roving path:

And though it in the centre sit,

Yet when the other far doth roam,

It leans, and hearkens after it,

And grows erect, as that comes home.

In later life, when responding to Aubrey’s Natural History of Surrey, Evelyn noted that ‘Surrey is the land of my birth, and my delight; but my education has been so little in it by reason of accident’ that he was ashamed to be so ignorant of it. But he hailed Wotton for being ‘environed as it is with wood (from whence it takes its denomination)’. Surrey was a territory ‘capable of furnishing all the æmoneities of a villa and garden, after the Italian manner’, replete with prospects, green hollies and ‘sugar-loaf mountains which with the boscage upon them, and little torrents between, make such a solitude as I have never seen any place more horridly agreeable and romantick’ (MW, pp. 687–91). He had been allowed by his elder brother George to augment the grounds with a study, fishpond and ‘some other solitudes and retirements’ (Diary, II.81; see illus. 8). Its landscape, above all its woodlands and gardens, would be the inspiration for and solace in his life, inclining him to establish useful and thoughtful gardens in the light of both his Continental travels and a concern for the livelihood and needs of producing English timber. Wotton was for him, in his measured but deliberate patriotism, what in his Numismata he apotheosized as ‘our British Elysium’ (p. 323): ‘Few Nations that I know of under Heaven (on so short a time) consisting of so many Ingredients . . .’.

5 John Aubrey’s sketch of Wotton House and its grounds.

The family had been farmers since the late fifteenth century, though a great-grandfather had been attached to the court of the young Edward VI. During Elizabeth’s and James I’s reigns it had prospered under Evelyn’s grandfather, George, as purveyors of gunpowder; thus Evelyn, writes John Bowle (p. 6), was the ‘grandson of a tycoon of the armaments industry’. In 1673 Evelyn wrote to Aubrey that he recalled how ‘many powder mills’ had been erected by his ancestors along the stream and ponds around Wotton. Despite the collapse of the gunpowder industry, the family yet possessed land, and John’s father, Richard, lived his life in the country and ‘in good husbandry’. He was well-off, an esteemed local official, the supporter of a grammar school and almshouses at nearby Guildford, a Justice of the Peace, and served for a while as High Sherriff of the county. He declined, as his son would do later, any further honours or a knighthood. Wotton, then, could be held up as a model of the gentry estate, which – beyond the great aristocratic houses – was an exemplary fulcrum of the English nation.

Evelyn’s education, such as it was, had a shaky start in the ‘church porch at Wotton’, and thereafter took place in his grandfather’s home and in the household of his grandmother’s second husband near Lewes in Sussex, where in the Free School he acquired Latin and some French, and an inclination for drawing, of which his father disapproved. He refused to go to Eton, though his father wished it, on account of its harsh disciplinary regime (though he later chose to send his grandson there), and in this he was supported by his grandparents. He returned occasionally to Wotton: in September 1635 he was summoned home when his mother was ill. Her death at the end of 1635, distressed by the death in childbirth of a daughter, Elizabeth, would be a sad domestic motif in Evelyn’s own lifetime.2

In May 1637 Evelyn went up to Oxford as a fellow commoner at Balliol, where he matriculated on 19 May; his older brother was already at Trinity (where Aubrey would later matriculate in 1642), and his younger brother, Richard, would join him at Balliol in 1639. A few annotations that Evelyn recorded in A New Almanack and Prognostication for the year of our Lord God 1636 and 1637, now held in Balliol College Library,3 do little to account for his life there, apart from recording prognostications on weather and some pretentious notes on human anatomy and the ‘working of the heavenly spheres’; it is against these commonplaces and quaint ‘verbosities’ (Bacon’s word) that Evelyn and members of the Royal Society would work. He made friends with a fellow undergraduate, James Thicknesse (who became a fellow of Balliol in 1641), one ‘learned and [of] friendly Conversation’, and with whom he would travel through Europe in the years after 1643.

He began early with an interest in new places, new ideas, new stimuli, by joining his brother in a trip to Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight, and then in May 1639 taking a ‘short journey of pleasure’ to Bath, Bristol, Cirencester and Malmesbury, after which he spent the summer at Wotton. After returning to Balliol at the end of the year (nobody then exactly ‘kept terms’ at Oxford), he left permanently in February 1640 without a degree – getting one was both expensive and unnecessary. He went first to Wotton where his father was ill and then, with George, to take up lodgings in the Middle Temple. Here he would, at his father’s wish, submit himself to what he himself called ‘th’impolish’d study of law’. Both brothers had been admitted earlier to the Bar (in 1636) by their father.

England was already much disturbed by the long simmering conflicts between Charles I and Parliament. Evelyn witnessed the Short or ‘Addled’ session of Parliament of 1614 and then the Long Parliament that the king was forced to call in November 1640, which Evelyn (in retrospect) termed ‘that . . . ungrateful and fatal Parliament; the beginnings of our sorrows, for 20 years after and the ruin of the most happy Monarch’. Both city and Court presented themselves as ‘often in Disorder’, with Lambeth Palace ‘furiously assaulted by a rude rabble from Southwark, set on doubtless and formented by the Puritans (as we then call’d those we now name Presbyterians’ (Diary, I.18).

If the state was in disarray, Evelyn’s family also suffered, with his father’s illness throughout the summer of 1640 ending with his death on Christmas Eve. Evelyn stayed at Wotton through the summer of 1641, though visited London for the trial and execution of the Earl of Strafford: ‘under the cognizance of no human-Law, a new one was made, not to be a precedent, but his destruction, to such exorbitancy were things arrived’ (Diary, II.28). With his elder brother now installed at Wotton and the state of the nation much disturbed, the nineteen-year-old John choose to flee ‘this ill face of things at home’ and take himself to the Low Countries. After a brief return to England later that year, he resumed his European adventures in 1643 and was away for the best part of six years. Exile would prove an apt education if the country could ever recover its stability.