I have observed so many particularities [in Continental gardens] as, happily, others descend not to.

A gardener’s work is never at an end.1

EVELYN’S SEARCH FOR a place to live with his new wife (and soon thereafter a son) found him staying at his wife’s ancestral home in 1652. It was an Elizabethan gabled house of three storeys that Evelyn would later declare as ‘ruined’ and in need of endless refurbishment, which turned out to be costly.2 He acquired the lease first from the Commonwealth in 1653, and in 1663 again from the Crown, following its return. While staying at Sayes Court, he made offers on one property, then also bought and sold another, and, disappointedly, also failed to purchase Albury, of which he had good memories because of his visits and acquaintanceship with the Earl of Arundel (see Chapter Seven). In the end it was Sayes Court that became his home and where he would make his garden; the latter, in his wife’s words, would be ‘his business and delight’.3 He would tell Cowley in 1666 that gardening was ‘the mistress I serve and cultivate’ (LB, II.436). Yet it was also, in his more morbid moments, but his ‘poor villa and possessions’, a phrase often used in letters to his brother or to Benjamin Maddox in 1656 (LB, I.157 and 174). He confessed to Jeremy Taylor that they were ‘indeed gay things’ and he apologized to him for living in a ‘worldly manner near a great city’ (LB, I.170). As he frequently consulted with Taylor on ‘spiritual matters, using him . . . as my Ghostly Father’ and who occasionally reprimanded his worldly life, this response reveals one side of Evelyn’s personality, a melancholic manner that could be muted or even overcome when his gardening interests took over; and to be in thrall to a ‘great city’ as opposed to a country estate in Surrey, for example, did not wholly suit him. It suggests, too, how much Taylor, in his concern that Evelyn was translating Lucretius, would contribute later on to his unwillingness to finish the ambitious manuscript of ‘Elysium Britannicum’; as Frances Harris argues, his pride and enthusiasm for his house and garden would ‘become a matter for confession and self-castigation’ in the 1680s.4

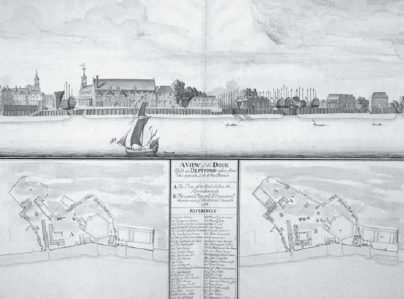

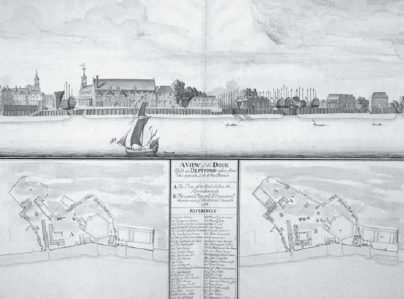

The site at Sayes Court was not promising – simply fields, a few elms, small orchards, in the furthest northwest corner ‘an extravagant place mangled by digging gravel’, and an awkward juxtaposition to Deptford dockyard (illus. 18); but, as he wrote to Mary, he would take it on and make it tolerable by putting in order its ‘conveniences, and interests annexed to it’. Work began on bringing the house and some essential service buildings into better shape, and its southern entry was given a classical porch. By 1653 Evelyn’s laboratory was acquiring the necessary apparatus of furnaces and other equipment. But the garden was clearly his main hope and objective. A plan of this ‘villa and possessions’ from 1653 suggests what arrangements Evelyn took over, but also what refurbishments of the house itself and the gardens were either made or envisaged. The plan – the handwriting and draughtsmanship of which are uncertain – is numbered throughout, and a long, itemized list down the left-hand side of the sheet annotates its ‘particulars’, to which some references will be made (illus. 19).5

An approach road across fields from the south crosses a walled courtyard to a paved porch with Doric columns. Inside was a typical and not always coherent Elizabethan house, but now evidently reorganized: a ‘hovel’ has become a ‘buttery’, a ‘clockhouse’ becomes a withdrawing room for the parlour, a storehouse turns into a bedroom, and a cheese house into a ‘pastry’. There are ‘new cellars, much enlarged, formerly an hovel’, more ‘lights’ and windows throughout, a kitchen sink ‘elevated and altered’. Mary Evelyn’s ‘Closet of Collections’ is established above the porch, while Evelyn’s new study is explained as ‘This I have built from the ground, so that my Study is 23 foot long, & 11 broad besides a little Study within it near half as big.’

18 Two plans and ‘A VIEW of the [Royal] DOCK Yard at DEPTFORD taken from the opposite Side of the Thames’, 1698, probably by the then Surveyor of the Royal Navy, Edmund Dummer.

19 Plan of Sayes Court (then in Kent), Evelyn’s home from 1652 to 1699, showing the Oval (top) and Grove (centre). A detail, not showing the list of ‘particulars’ at the left of the plan.

The exterior, too, was a medley of small spaces, some walled courtyards with walks and arbours, as well as utilitarian functions: a pump and cistern, a pigeon house over ‘my [new] elaboratorie’ with its portico ‘towards the private garden’, an aviary, a beehive ‘in the private garden’, a wood yard, milking close, a brew house that replaced stables, a freshly dug carp pond that was replenished at high tide through a culvert from the Thames, and so on. The whole site (illus. 20) lay between the Deptford dockyards, with, just beyond, the Thames, which also fed the horse pond. From a banqueting house, above where the new oval garden would be established, a long walk (‘526 foot long, 21 broad’) would lead to an island with a moat, and from there a passageway and then stairs led to the Thames along the mast dock. Beyond these necessary domestic and working spaces were those parts of Sayes Court that constituted Evelyn’s garden of pleasure.

Despite the fact that Sayes Court no longer exists (and indeed its site is barely registered these days, though there are some vague plans to recreate part of it6), Evelyn’s large commitment to garden writing and garden-making has meant that Sayes Court has attracted considerable attention, and rightly so. Over the forty years in which Evelyn made, tended and revised his garden, he encountered excitement, expense, disappointments and certainly the need to understand how to domesticate what he had witnessed in his European travels, as well as his readings about them, to local conditions of place, location and society. No garden is ever ‘finished’, whether it is just one site or an attempt to establish a national typology, such as he embarked upon in his ‘Elysium Britannicum’ as he was beginning his gardening at Sayes Court; every garden is different, even though we may try to generalize about them. Gardens also suffer from weather and climate changes, and however much we force them to respond to our wishes and desires, they cleave to local conditions. Sayes Court was no exception.

Given Evelyn’s own foreign experience and his wide reading in Continental treatises, he could hardly settle in mid-seventeenth-century England for recollections of an Elizabethan gardenist past, even if the house itself and its larger relationship to its surroundings remained somewhat old-fashioned. There were, indeed, some telltale gestures to that past, like the carved mottoes that he placed over doorways in the house or hung from trees in the garden, for in ‘Elysium Britannicum’ he noted the incidence of ‘Impresses, Mottos, Dials, Escutchions, Cyphers and innumerable other devices’ (EB, p. 75). Yet to bring hortulan culture into the early modern world required attention to a host of often competing concerns: foreign forms and ideal devices jibing with local and native circumstance; personal taste with a sense of national imperatives; enthusiasm for a new gardening with a recollection of the pleasures of melancholy in garden traditions; keen, careful and modern observation of plants and animals requiring, nonetheless, some respect for ancient lore on both planting and husbandry; plants from abroad that needed to tolerate the local climate and plants from English nurseries or acquired from acquaintances. It also required a dialogue between a respect for celestial bodies, acknowledging ‘prognostications’ and ‘astrological niceties’ (though Evelyn was ‘no friend’ of them, notes Mark Laird), and whatever intervenes in an actual garden on the banks of the Thames – prodigies of weather, animals (like moles, frogs, mice, snails, noxious caterpillars, yet also the glorious butterfly) and bad air that ‘kills our Bees and Flowers abroad’, as Evelyn noted in Fumifugium (see Chapter Six). He seemed particularly eager to distance himself from the ‘nice and hypercritical punctillos’ that astrologers imposed upon gardening matters.

20 Plan of house and Docklands from Evelyn’s Miscellaneous Writings (1825). This is a redrawn map after a sketch by Evelyn (BL Add MSS 78629A) from about 1698, showing the adjacency of Sayes Court to the dockyard, which increasingly came to disturb him.

It is useful to situate Evelyn’s garden work, particularly his garden vocabulary, in a larger context of European practice and publications.7 His range of reference was considerable: beyond his visits to many gardens in the Low Countries, France and Italy, he drew on books by Nicolas de Bonnefons (which he translated), Charles Estienne and Jean Liébault, Olivier de Serres, Claude Mollet and Jacques Boyceau, as well as native writers like Thomas Mill, John Parkinson, Stephen Blake, Thomas Hanmer and Gervase Markham. But this considerable learning raises a question: how do those formal devices and foreign terms translate into an English garden practice and vocabulary of the mid-seventeenth century?8 These terms can be, as Mark Laird showed well, ‘diverse and rather elusive’ when Evelyn uses them (Evelyn DO, p. 175).

Though Evelyn was undoubtedly composing the ‘Elysium [or ‘Royal’] Britannicum’ during the 1650s, since he published a synopsis of it, which he communicated to Sir Thomas Browne and others, in 1659, it seems that what he was doing at Sayes Court was his primary focus and was his own personal project for a gentry (and not a royal) garden. And while the making of Sayes Court’s gardens obviously contributed to modelling his ‘Noble, princely, and universal Elysium’ in the unfinished book, it was, as he well knew, only in specifics and hands-on practice that a gardener and designer could see what he was doing.9 While he was constantly alert to what ancient authorities such as Columella or Virgil in his Georgics could teach him, it was the actual work at Sayes Court that directed his ideas, and it was the wisdom and aphorisms about his own work there that sustained both his Kalendarium Hortense, published with Sylva in 1664, and the ‘Directions for the Gardener at Sayes Court’ that he wrote 22 years later (1686) for an apprentice.

On what once had been an orchard and ‘one entire field of 100 acres’, Evelyn saw the beginning of ‘our Elysium’ in ‘gardens, walks, groves, enclosures & plantations’. Two major interventions were an oval grove at the south of the garden and another grove towards the north; between them was an elevated terrace walk, edged by a holly hedge on one side and with a hedge of berberis towards the grove. Evelyn began these designs with both very specific memories of Morin’s garden in Paris, which he had visited in 1644 and again in 1651, and a more generalized recollection of the many groves, bosquets, boschetti, flower displays and cabinets in France and Italy.

So when in January 1653 he started to set out his Oval Garden in imitation of Morin’s garden (see illus. 23), he wrote to his father-in-law that ‘we are at present pretty well entered in our gardening’. Mark Laird’s reconstruction shows two ovals within a rectangle, marked with sentinel cypresses,10 the inner oval set as a parterre, the outer one in grass, with a raised mound and ‘dial’ at the very centre11 surrounded by eight cypresses; walks surround the two ovals and also cross it from north to south and from east to west. Outside the larger oval are ‘wildernesses’ or groves, with on one side an ‘evergreen thicket, for birds[,] private walks, shades and cabinets’ and, on the other, another walk also ending with a small cabinet at both ends. By May, Evelyn was also telling his father-in-law that his own Oval would ‘far exceed [Morin’s] both for design & other accommodations’. ‘Exceeding’ allows several meanings – better or later in time, because we improve upon what went before; but also more apt, more suited, or more accommodating, to what that particular garden needed. Laird notes that a ‘hierarchy of elements’ is introduced: a miniature version of what pertains in larger spaces, where small and low-level planting gradually gives way to bigger and taller items behind, or (in this case) where the large forms are established at its edges, appropriate to the oval.

The Grove, to the north, echoed those Evelyn had seen in France and above all in Italy. It has the overall aspect of a Baroque bosquet, but experience of the interior must have been a pleasing meander of surprises and planting. Rectangular, 40 by 80 yards, it was divided into eight, with walks from each corner and side that converged upon a central mount at the centre, ringed with laurel. But inside, beneath the canopy of over five hundred standard trees, with an under-storey of ‘thorn, wild fruits, greens, etc’, its shape was less apparent, the richness of leaf and form much more various; some of the walks even morphed into what Evelyn called ‘spider’s claws’ – dead-end alleys that twisted into little cabinets with a ‘great French walnut tree’ at the centre of each. After five seasons, Evelyn would think it ‘infinitely sweet and beautiful’.

But ‘accommodations’, noted in the letter to Sir Richard Browne, involved other things. Sayes Court was, Evelyn wrote in 1664 (if not before), his ‘villa’;12 yet in each move of that useful Latin term, translated without alteration into the Italian ‘villa’ and then directly into the English villa, it acquired fresh significance, not least that in Evelyn’s case it was only leased. While the word remains the same, the culture and use of a ‘villa’ on a bank of the Thames would have a different feel, a new attention to different circumstances in the life of a seventeenth-century Englishman, even if the Latin or the Italian term brought its owner some appreciable and rich associations with cultures elsewhere. Even the measurement of a foot of ground was slightly different in France and in England. But situation, scale, climate, plants, animals, birds and vermin were also different. The soil at Sayes Court needed enrichment with hefty mixes of lime, loam and cow dung.13 Evelyn gathered plants from many sources; some locally in east Greenwich, but many from the Continent, some of which needed careful tending in Surrey. From his earliest days at Sayes Court he was sending his father-in-law requests for cypress seeds, for what he had ‘did not prove according to my expectation’, or soliciting ‘half a dozen bearing trees from Paris’, along with a list of plants ‘all unknown to me’. He urged Sir Richard to consult La Jardinier françois with its catalogue ‘of all sorts of fruit in France, out of which you will be easily able to collect what kind are best’.14 As late as the 1690s he was still obtaining, from Flanders, ‘50 roots of the Royal Parot Tulips’ and ‘100 roots of Ranunculoes’ (Diary, IV.648 and V.59).

Different machines were also needed in an English garden. This was a time when various virtuosi were devising ways of measuring rainfall or wind speed, and using thermometers and barometers. The ‘Elysium Britannicum’ devotes pages and drawings to these necessary accommodations to English gardening: not only the tools required but instruments for watering (see illus. 32, where no. 43 is a water truck), or to measure and predict weather conditions, like the hygroscope, or the ‘thermoscope or weather-glass’ that would ascertain the degree of wet or dry in an English garden (EB, p. 151). In his manuscript ‘Directions’ of 1686 he listed a ‘Hot-bed’, while a new edition of the Kalendarium Hortense in 1691 added remarks and diagrams for heating systems and a greenhouse, so that tropical plants, like the banana tree, could thrive in England. Evelyn is credited in the OED with first using the word ‘conservatory’, in the 1664 edition of the Kalendarium, but he had seen one in 1644 at Cardinal Richelieu’s garden at Rueil (Diary, II.109, though that reference might well be a subsequent addition when he wrote up his notes). He continued to be interested in systems to maintain plants inside; he admired the conservatory and (somewhat confusingly) also a greenhouse at Euston Hall in 1677, and had visited in 1685 John Watts’s subterranean stoves in Chelsea (Diary, IV.462). He was convinced now that, rather than utilizing stoves to create heat, experimenting with solar heat would inaugurate an English paradise of perpetual fruiting, since it may not be too ‘late for me to begin new paradises’.15

Evelyn was eager to note how his plants, improvements or accommodations made good sense of their translation onto English ground. Of his evergreens, Evelyn wrote that ‘an English garden, even in the midst of winter, shall appear little inferior to the Italian’. His ‘glorious nursery of 800 trees’ transplanted in 1653 was ‘Two foot high’, and ‘as fair as I ever saw in France’. Again, writing of palisade-hedges, espaliers and close-walks, he saw that we have brought aliterus [Rhamnus alaternus] into ‘use and reputation for those works in England’ (my italics).

The Kalendarium Hortense that Evelyn appended to the first edition of Sylva in 1664 set out ‘An almanac directing what [the gardener] is to do monthly throughout the year’, for an earthly paradise needs attention and weeding. He encouraged ‘an extraordinary inclination to cherish so innocent & laudable a diversion [gardening], and to incite an affection in the nobles of this nation towards it’ (my italics). Each month are noted the fruits and flowers that are ‘in prime’, or ‘yet lasting’ so that they can be used early in the next year. In both the orchard and ‘olitory’ (Evelyn’s coinage for the vegetable garden) and in the parterre and flower gardens, the tasks were listed – dealings with wasps, tending bees (in April, ‘open up hives for now they hatch’), feeding birds in the aviary before they breed, sweeping and cleaning paths of leaves in October and again in November, lest worms pull them into holes. Once December is reached, the year starts all over again: ‘As in January, continue your hostility against vermin.’

But if some accommodations for English garden-making were necessary or even welcomed, others were not. Vermin might be controlled, but storms could not be avoided. If gardening was the result of planning and careful maintenance, then what Laird terms ‘an environment of chaos as much as stasis’ (Milieu, p. 116) at Sayes Court was ‘troubling’ and unforeseen both for plants and indeed people. Deadly disease felled Evelyn’s daughter Mary and his servant Humphrey Prideaux, both dying of smallpox. Storms had certainly to be accepted and (unlike humans) their consequences could be repaired in some measure: ‘Extraordinary storm of hail and rain. Cold season as winter and wind northerly near 6 months’, Evelyn wrote in his Diary in June 1658; it felled ‘my greatest trees’ and destroyed winter fruit. The next day he reported the grounding and slaughter of a whale in the Thames.

Evelyn was gardening in what we would now call the ‘end of the Little Ice Age’.16 He chronicled the bad winter of 1685–6 in a report to the secretaries of the Royal Society (LB, II.732–5, later published in Philosophical Transactions, no. 158; see MW, pp. 692–6). While elms and young forest trees were unscathed, exotics like the cork tree would hardly recover, cedars were lost, pines, rosemary and laurel were dead or discoloured; he lost a few fish and his long-lived tortoise. But nightingales were ‘as brisk and frolic as ever’; by 14 April 1684 he was welcoming their arrival from Africa, and noting that this migration deserved proper study by ornithologists (MW, p. 696).

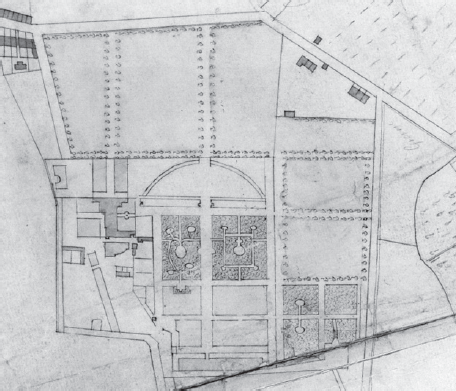

It was that devastating winter of 1685–6, when the Thames was frozen, that impelled Evelyn to rethink his garden layout. A new plan from February (illus. 21) shows what he envisaged, and that plan is supported by two surveys of the late 1690s that show what was implemented (illus. 22). Essentially, he eliminated the Oval Garden entirely, and modified and extended the Grove.

The new half-moon of grass or ‘bowling-green’, surrounded by plantations, was twice the size of the previous Oval; at its centre and head was still the banqueting hall, which faced across the grass and down the original walk to the moated island. What is interesting about this enlarged hemicycle is that it may also have recalled two Continental designs, though in both cases they are substantially revised for Sayes Court. One model was the demi-lune that Evelyn had observed at the Château de Richelieu in September 1644; but now it was cleared of the elaborate parterre work, and what in France had been a ring of statues is replaced with holly and fruit trees, with gooseberries and currant bushes, strawberries and violets that fill out the corners or ‘triangles’ of the half-circle. But this new bowling-green also recalls the shape of the artificial echo that he saw in the Tuileries and sketched for his ‘Elysium Britannicum’ (see illus. 11), though the French space was greater than at Sayes Court and its half-circle was graced with two lines of trees; nor did it enable an artificial echo. Such hemicycles or demi-lunes are nothing unusual in seventeenth-century European garden design, but Evelyn accommodates those foreign recollections into a grass lawn and a celebration of fruit trees, many recommended by John Parkinson in 1629, that produced fruit during an English summer and some that lasted through the winter (the 1684–5 plan contains lists of what he was planting17). And his ‘Directions’ for the apprentice gardener, composed soon afterwards in 1686, now contained careful advice on how to deal with the grass of the bowling-green – ‘rolled and cut once a fortnight, with ease’.

21 New plan of the southern part of Sayes Court, dated February 1685.

22 Detail of map from c. 1690 by John Grove (?) of the later layout of Sayes Court, showing the new oval and the matching pair of groves.

The enlarged area of the former oval is now answered by a pair of groves either side of the walkway that leads from the banqueting hall; the original one stays the same size, but loses some of its regular grid of allées, though retaining the ‘spider’s claws’; the new and matching one to the west is larger, and has a square of walks with a central cabinet and one at each corner of the square. Both groves continued to be filled with varieties of trees.

Whatever the motivation for Evelyn’s far less intricate layout – a need to reduce maintenance, loss of funds, an inclination to simplify, compensation for either the bad weather or his own age (he was by then 64) – Sayes Court was still an acknowledgement, if more distant, of Continental garden design. It had been from the first an ‘invented’ garden, playing with elements of Italian and French design, but now it was even more so, yet the invention more his own. However, whatever it was, it was not proleptic, no anticipation of the landscape ideas that, twenty or thirty years later, would either in format or usage begin to shape the design and thinking of English garden-making.

In his introduction to Kalendarium Hortense Evelyn notes that dressing and keeping an Eden necessarily required that it be kept ‘continually cultivated’; yet it was also ‘a labour full of tranquility’. In 1686 Evelyn took on an apprentice gardener, Jonathan Mosse, for whom he wrote ‘Directions’, including what exotics would be able to thrive in England. These instructions were an agenda of everything he had learned on the ground of Sayes Court, listing fruit trees suitable for different sectors of the garden (Fountain Court, Greenhouse Garden, the ‘Island’ and so on), forest trees and ‘trees for the Grove’, the necessary tools to be kept and used, ‘measures which a Gardiner should understand’, and noting everything from ‘dunging and compost’ to preparing salads for the table ‘according to the seasons’. Also included was a careful list of ‘Terms of art used by learned gardeners’: some were straightforward, but presumably useful for an apprentice gardener – ‘Estival, Autumnal, Hyemal, the same as Brumal’ to designate what could flourish in which season, or ‘Botanist, One who has knowledge of plants’. Others were more unusual, like ‘Aspect’ (‘the quarter of the heaven, East, West, North & South’), ‘digest’ (‘to rot and consume like dung’), or ‘mucilage’ (‘clammy stuff, such as in yew-berries’). In notes on ‘garden and physical plants necessary to be known and had’ for the physic garden, the plants should be ‘set in alphabetical order, for the better retaining them in memory’.

Frustrated by his inability or unwillingness to publish his ‘Elysium Britannicum’, he pulled a section headed ‘Of Sallets’ and published it separately in 1699, as Acetaria, a Discourse of Sallets.18 This clearly drew upon his work at Sayes Court, and now he enlarged upon the ‘Directions’ he had penned for its new gardener by discoursing on the ingredients of a salad, the herbs and vegetables to be used therein. But now he moves from Baconian, practical matters into ‘a glorious disquisition on primitive innocence and the early state of the world’: Adam and Eve lived on salads, and Milton is summoned in support of the ‘wholesomeness of the herb-diet’ – ‘vegetarian as by God’s will’ (writes Graham Parry). Evelyn was clearly something of a connoisseur on the preparation of salads, though (as Keynes notices in Bibliophily, p. 237) his dedication of Acetaria to the Lord Chancellor and President of the Royal Society is marked by nothing if not ‘his usual long-winded solemnity’ – what the writer himself describes as ‘to usher in a trifle, with so much Magnificence’. To the Duchess of Beaufort, however, he explained that it was ‘but of an handful of herbs’; they were, he added, ‘yet the products of the same great Author’, by which we presume he meant God, not himself, ‘and have their peculiar virtues and uses too’.

The house and garden at Sayes Court has long since disappeared, while the Evelyn family home at Wotton survives. If Evelyn had read Ben Jonson’s poem ‘To Penshurst’, for he certainly knew Penshurst Place in Kent,19 he would have appreciated much of the poem’s praise of the estate. In July 1652, the year he himself settled at Sayes Court, his Diary records a visit to Penshurst with his wife, newly arrived from France: it was ‘finely water’d’, once famous ‘for its gardens & excellent fruit’ and was marked by the ‘conversation’ of those who frequented it. Jonson praises the Sidney estate for its modesty, for boasting neither marble nor ‘polish’d pillars, or a roof gold’; there were walks for pleasure and sport, and it was peopled with dryads on its mount, Pan and Bacchus, and all the Muses; praise is notably bestowed on its woods (‘the broad beech, and the chestnut shade’), which Evelyn would have appreciated. Altogether, it shows itself as an antique and sacred place that echoes much of Evelyn’s own visions of a paradisal garden sustained by ancient virtues and modern skills.

Jonson ends his celebration by comparing Penshurst with ‘other edifices’, ‘proud, ambitious heaps, and nothing else’ that aristocrats had built. Their ‘lords have built, but thy lord dwells’. That is a supreme compliment. Yet one might wonder whether Evelyn would have agreed – whether he would have found it hard to say he dwelt, in the full richness of that word, at Sayes Court. It was certainly similar in that it did not pretend to aristocratic or royal power, but it was, when all was said and built, not the home that Evelyn wanted or could in fact preserve. When in the 1690s Evelyn finally repossessed his true family home in Wotton, Sayes Court was let, first to Vice-Admiral Benbow and then to the young Tsar of Muscovy, Peter the Great, who wrecked the place – smashing the windows, ruining Mary’s best sheets, damaging pictures and driving his wheelbarrow through the hedges.