ONE DOES NOT GO FAR IN READING Evelyn’s writings without realizing how much he was concerned with exchanges between modern ideas and ancient wisdom on a variety of matters. His long, deliberate and pedagogical letter of 1656 to Edward Thurland (LB, I.190–93) is a virtual essay on the subject of prayer, a barrage of citations for and against its topic, from the classics (Silius Italicus, Democritus, Pythagoras, Plato, the Stoics, Cicero), to St Paul and St Augustine, and thence to moderns like Lancelot Andrewes, Henry Hammond and Henry More. While others letters are less instructional, his public writings still dilate upon a similar and pertinent repertory of influences; indeed, he seems unable to write without weighing in with references to relevant authorities. In this seventeenth-century ‘battle of ancients and moderns’ Evelyn occupies a considerable and visible place as both a careful, yet sometimes awkward, adjudicator of those rivalries.1

A crucial and related aspect of the ‘battle between ancients and moderns’, especially for those committed to the modern, was the appeal to a progress of the arts, that is to say a transference, and so an improvement, of ancient ideas now brought into England. But what if the ancients were after all better than the moderns? Nobody who was both a Baconian and a member of the Royal Society is likely to have believed that the ancients were better, but Evelyn was not inclined to dismiss ancient wisdom in matters that concerned him. Charles Perrault’s Parallèle des anciens et des modernes en ce qui regarde les arts et les sciences (1688–97) maps the progress of the arts with a metaphor that would have appealed to Evelyn’s domesticity: ‘should not our forefathers not be regarded as the children’, writes Perrault, ‘& we as the Elders and true Ancients of the world?’ Such an argument turns the tables on those who wished unreservedly for a new modernity – like Charles’s brother, Claude Perrault2 – by seeing a family relationship, maybe even a physical resemblance, between ancient and modern writers. A similar argument on the progression of the arts is made by the French gardener Jean-Baptiste de La Quintinie, translated by Evelyn in the 1690s: the French text praises the art of pruning as an ancient practice that ‘begun not in our days, for it was held [‘among the curious’] as a maxim many ages since, as appears by the testimony of the ancients [the margin names Theophrastus, Columella, Xenophon]; so that, to speak the truth, we only follow now, or perhaps improve what was practiced by our forefathers’. After all, the ‘Georgical’ Committee saw Virgil as both an ancient and yet as a ‘child’ who needed to be raised to be a ‘truer ancient’, re-educated in a modern family and culture: Dryden would do it with his translations, as did Pope in his imitations of Horace’s epistles and satires. Evelyn was performing the same in his reinvention of Albury’s garden terraces. For Evelyn, all wisdom, knowledge and arts from the ancient world, sifted, interpreted and ‘translated’ in the fullest sense, were no longer the property of a distant past but themselves modern and vital.

To the reader of his Sylva he explained that ‘to improve natural knowledge, and enlarge the empire of operative philosophy [is achieved] not by the abolition of the old, but by the real effects of the experimental; collecting, examining, and improving their scattered phenomena’. While Evelyn may have, too often, enjoyed playing rhetorically with materials in the battle of ancient and moderns, as in his letter to Edward Thurland, he was also keenly alert to the need for his contemporaries to understand the newness of the past. Horticulture and architecture were obviously and essentially modern, for both were designed for current usage by a process of reinterpretation and renewal. Any recourse to ancient wisdom meant that it needed to be ‘read’ now, in a contemporary language. Thus Evelyn, writing to Cowley, saw that the world of nature needed, ‘from the variously adorned surface [of the ‘Whole Globe’] to the most hidden treasures in her bowels’, to be unlocked, and their ‘abstrusest things’ made ‘useful and instructive’.3 That is what the Royal Society has done: showing that the ‘real secrets useful and instructive’ were better than anything anyone had done in the ‘last 5,000 years’, including Bacon himself. And that contemporary ‘showing’, that demonstration, was a crucial act of translating the world into words, which is why Evelyn needed a poet like Cowley to prepare the prefatory poem for Sprat’s History of the Royal Society.

Evelyn worked in two ways to make sense of the ‘battle’ of rival authorities and the progression of the arts. First, by reviewing ancient wisdom and expounding its application to his own country, a form of translation of ancients into modern culture; specifically, of course, by actual translations of texts that lent support to modern work without neglecting what earlier arts had recommended. Second, by his garden and horticultural work, which he pursued both through the Englishing of foreign texts and by his own practical activities. Here there were both successes – Sylva above all, along with recommendations made and executed for other landscapes like Albury – and failures, most crucially his inability to bring ‘Elysium Britannicum’ to a conclusion and publication.

In all these endeavours he needed to adjudicate between ancient authorities (accessed entirely through ancient writings, as few actual sites of gardens existed) and modern work in garden-making, painting, architecture, urban design and engraving, which came as much through images and what he saw around him as through words. All of these, however much these productions acknowledged and borrowed from the ancients, were inevitably modern: gardens may imitate what texts implied of ancient layouts and formal properties, but the plants, the maintenance and their uses were all contemporary, as were the people who designed them. Evelyn’s years in Europe gave him confidence to expound modern conceptions and performances in various arts, while his belief in the importance of direct observation during his years abroad reinforced the relevance of what he wanted to recommend in England.

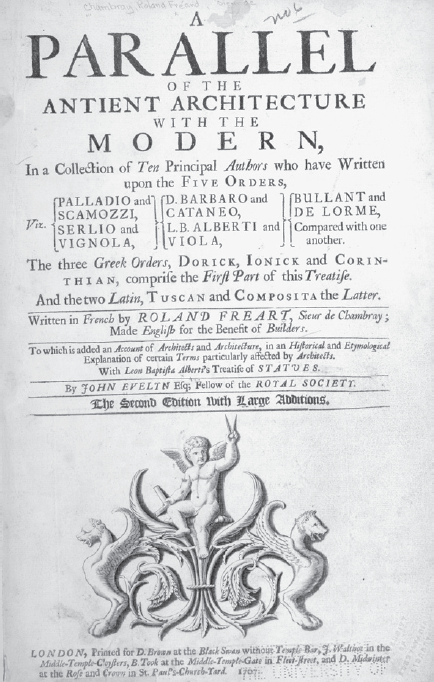

The primacy of modern Renaissance architecture was focused in Evelyn’s translation and presentation of Roland Fréart de Chambray’s Parallèle de l’architecture antique avec la moderne (illus. 38), with its first edition in 1664 and a second issue in 1680; another, posthumous, second edition, planned before his death, did not appear until 1707, and it included additions and paid tribute to Sir Christopher Wren. (In 1665 Wren, whose work Evelyn admired, went to France to observe French architecture at first hand.) Evelyn’s version of the Parallèle championed modern architecture in opposition to ‘the asymmetry of our [ancient] buildings, want of decorum and proportion in our houses’, from which ‘the irregularity of our humours and affections may be shrewdly discerned [that is, understood]’, as he wrote in its dedication to Sir John Denham. The dedication also praises the Frenchman’s Parallèle as being, more than any other study, a ‘safe, expedite and perfect guide . . . where, from the noblest remains of antiquity accurately measured, and perspicuously demonstrated, the rules are laid down; and from a solid, judicious, and mature comparison of modern examples, their errors are detected’. Yet Fréart’s conclusion was, in effect, very modern, seeing the arbitrary character of architectural proportions.

38 Title page of Evelyn’s English translation of Roland Fréart’s Parallèle de l’architecture antique avec la moderne, 2nd edition (1707).

Evelyn’s determination in his own account of architects and architecture, appended to his translation, also ‘addressed the loss of an adequate language’, notably in technical or ‘mechanical’ vocabulary in England compared to that in France.4 A similar concern with understanding the exactness of linguistic terms also drove his discussion in Sylva, where the Advertisement argues that ‘it was not written for the sake of our ordinary rustics’, but to improve ‘the more ingenious’; an exercise, then, in domestication for the ‘benefit and diversion of gentlemen, and persons of quality, who often refresh themselves in the agreeable toils of planting, and the gardens’. He admits that he ‘may perhaps in some places, have made use of (here and there) a word not as yet so familiar to the reader; but none that I know of, which are not sufficiently explained by the context and discourse’. Still, he appended a list where some curious terms were provided with a more straightforward, indeed English, gloss: a ‘coronary garden’ is a ‘flower garden’, ‘iconography’ refers to a ‘ground-plot’, ‘stercoration’ is ‘dunging’, ‘olitory’ is explained as ‘salads, &c belonging to the kitchen-garden, and ‘insolation’ glossed as exposure to the sun.

Fréart’s Parallèle de l’architecture was first published in Paris in 1650, and a copy of that French edition was catalogued in Evelyn’s library in 1687. He started his ‘interpretation’ of it in France in 1652 ‘to gratify a friend in the country’, then laid it aside, until an architect colleague in England, Hugh May, who had acquired ‘a most elaborate edition of the [original] plates’, urged him to complete it. His edition reproduced those plates and added his own ‘Account’ of modern architects and architecture. Copies were given to the king, the Queen Mother, Wren, John Beale, who had written Latin verses for it, and Sir John Denham, one of the commissioners of highways and sewers. Its discussion of the Greek and Roman orders are contrasted and compared in engravings and adjacent texts, ‘made English for the benefit of builders’, a claim that was endorsed by other virtuosi as well. A final addition takes up Leon Battista Alberti’s De statua (once again, noted as ‘first introduced into our language’). His tribute to Charles II, who ‘most resembles the Divine Architect’ (as he noted, it was ‘hard not to slide onto the Panegyrick’ mode), acknowledged ‘the impiety and iniquity of the late confusions’ and gloried in the accomplishments that were making ‘our Imperial city’ great.

Evelyn had clearly appreciated modern architecture in Europe and found occasion to applaud its arrival in England. He admired Inigo Jones’s Banqueting Hall in Whitehall and his classical portico (of 1633) for the old St Paul’s; the London squares of St James’s and Southampton (later Bloomsbury) revealed how elegant townhouses were coming into fashion, and Parliament had sanctioned the ‘regularity’ of the latter’s architecture. The mansion for the Earl of Clarendon (formerly Sir Edward Hyde), designed by Robert Pratt, whom Evelyn had known in Rome and who had an unrivalled knowledge of modern architecture, was (for Evelyn) among the ‘graceful and magnificent’ examples of English houses (Correspondence, pp. 177–8; though later he had reservations about its ‘pomp’, ‘costly & only sumptuous’: Diary, IV.321, 338). Wren’s Sheldonian Theatre, which Evelyn saw finished in 1669, was a thoughtful reworking of Roman models into a suitable assembly house for modern academics. At Wotton Evelyn’s brother had designed a Renaissance-style front to the grotto below the mount during the 1650s, maybe at his suggestion. In 1658 his Diary found ‘tolerable’ the facade of what would later be Northumberland House, finding that it was not ‘drowned by a too massy & clowdy pair of stairs’ (III.216): ‘clowdy’, his editor says may be a ‘slip’, but it does suggest the avoidance of ‘clouding’ or obscuring a set of stairs with a too-fussy elaboration; as such, it echoes Sir Henry Wotton’s advocacy of ‘plain compliments and tractable materials’. Evelyn’s proposal for a version of Solomon’s House (see illus. 24), made before the formation of the Royal Society, was firmly modern, despite its acknowledgement of Carthusian monastic landscapes, and copied a building that Evelyn had known well, Balls Park, Hertfordshire. And in 1664 he reluctantly admired parts of the house designed by Hugh May, an architect about whom he had reservations, at Eltham Lodge near Deptford, especially its views over the grounds. He accompanied Sir John Denham, famous for the prospect poem ‘Cooper’s Hill’ of 1642 and now Surveyor-General of the King’s Works, to Greenwich Palace, which Charles II wanted modernized. But they disagreed on what would be appropriate: Denham wanted a building on piles over the river, Evelyn – which suggests indeed that his judgement of Denham as a better poet than an architect was right – thought a handsome courtyard that saw the Thames as lying like a ‘bay’ before it would be better. He joined Denham and May on a commission to improve London’s thoroughfares; in 1663 he appreciated the installation of new paving stones in Holborn that would save innumerable women and children from injury on the streets. And, in August 1666 with Wren and others, he had surveyed the old ‘gothick’ St Paul’s and realized that it needed to be completely rebuilt. Indeed, it was so dilapidated that an engraving of it by Hollar was inscribed in Latin with the phrase ‘daily expecting collapse’.5

All of his earlier attention to architecture and urban sites when travelling in Europe and now his translating of Fréart gave him an opportunity, he thought, to intervene in the rebuilding of London after the Fire of 1666. And in doing so, he would be able to put into practice a modern, contemporary vision, and at its core the best elements of the antique, now ‘translated’. The Great Fire in the month following his visit to survey St Paul’s not only cleared the huddled city of its plague-tormented housing, but inaugurated a complete renewal of the city layout, building practices and a new St Paul’s. His Diary (III.459–63) recounts at more than usual length the destruction after the Great Fire: the ruined vaults, melted lead from roofs, calcinated stone, books burning ‘for a week following’ where stationers had secured their stock in the crypt of St Paul’s, fountains dried up yet water still boiling, the chains used as barriers across streets also melted, the lanes filled with rubbish; on top of which came riots, fuelled by rumours that the French and Dutch, with whom England was at war, had invaded. He, Mary and his son John watched the conflagration from the south bank of the Thames, and Sir Richard Browne asked his daughter to send some ‘Deptford wherries’ or a ‘small lighter’ to ferry his and others’ possessions out of harm’s way from his quarters in Whitehall. Evelyn later compared what he saw in the Great Fire to the burning of Troy, from which Aeneas escaped to found, eventually, the city of Rome.

Eleven days after the fire started, Evelyn presented Charles II on 13 September with his ‘Londinium Redivivum’, a survey of the damage and ‘a plot for a new city, with a discourse on it’. Such involvements in civic projects were far more congenial than some of his other civil service work (see previous chapter), yet his vision of a new London was never realized and the plan survived only in manuscript until printed first in 1748 and with its accompanying text appearing in many subsequent versions.6

There were many proposals for rebuilding the city: Evelyn noted that ‘everybody brings his ideas’, and the character of Sir Positive At-all in Thomas Shadwell’s Sullen Lovers (1668) claimed that he had himself constructed seventeen models of the new city! Plans and proposals came from Evelyn himself, from Wren (who had proposed his own scheme two days earlier), Robert Hooke (curator of the Royal Society), Peter Mills (a former City bricklayer with an architectural career as City Surveyor), another surveyor, Richard Newcourt, and one Captain Valentine Knight, who was arrested after saying that his scheme would much profit his Majesty’s revenue. All proposals envisaged a new city of regularity, with straight and radial roads, circuses and open squares, with clear and unencumbered locations of important and key buildings. Out of the ‘sad ruinous heaps’ Evelyn saw a city emerging that would ‘dispute it with all the cities of the world’, at once beautiful, rich in health and apt for both commerce and government.

Evelyn’s plan has come down in three engraved versions, though they are generally similar in profile (illus. 39). It brings a long, straight avenue from the Strand at Temple Bar in the west to a newly named Charlesgate, ‘in honour of our illustrious Monarch’, at the east. It first meets a double octagon, from which eight roads emerge like a star, then it crosses the ‘new channel’ of the River Fleet, passes between a College of Physicians and a Doctors’ Commons, and emerges before a new St Paul’s, set in an oval plaza from which two main roads go northeast (to the Guildhall) and southeast to meet the Thames. He made the riverbank and quays more imposing, with six openings and wharves facing the water, reminiscent of the harbour at Genoa. The Custom House next door to the Tower was connected inland to a square with the Navy Office and Trinity House. A specially enlarged square on the river held the Royal Exchange, from which another avenue led straight north to Moorgate and Moorsfield outside. The city gates would be rebuilt as triumphal arches and ‘adorned with statues, relievos, and apposite inscriptions, as prefaces to the rest within, and should therefore by no means be obstructed by sheds, and ugly shops, or houses adhering to them’. Twenty parish churches are marked on the plan with a small cross, and public fountains with a small circle.

39 Plan of new London, undated, but mid-18th century: as Evelyn was never knighted, this caption refers, by mistake, to a later baronet.

The Guildhall is modelled after Amsterdam’s Town Hall (1647–55) by Jacob van Campen, and Evelyn’s plan owes much to his own knowledge of Rome and its urban planning under Sixtus V and the architect Domenico Fontana, though in London the Italian’s ‘stational liturgy’ was replaced by customary English pageantry. Also implied is the translation of Continental landscape forms into elements of urban layouts, though former indigenous place names are retained: a series of rectangular, oval and circular piazzas punctuate the avenues, as they did along Continental garden walks, and the hemicycle (which Evelyn later adopted in the 1680s reworking of Sayes Court) is used here to enclose the Fish Market that faces over London Bridge. Evelyn’s plan and programme were at once modern, attentive to much of what he had seen and admired in Europe, and yet would inspire a ‘modern Rome’. Even those who favoured rebuilding the old city on its old foundations wanted it made not with timber, but with bricks, if not with marble.

It was Wren, the accomplished professional, who seems to have made the more thoughtful plan, but he still may have exchanged ideas with the amateur Evelyn, whose scheme got submerged or subsumed under others. Evelyn told Samuel Tuke that ‘Dr Wren had got the start of me’ (LB, I.421), yet Joseph Rykwert in The First Moderns captions an illustration with ‘Plan for the rebuilding of London submitted by Christopher Wren and John Evelyn, dated 1748 after Vertue’ (though it is not clear to what extent this engraved plan represented that collaboration). Evelyn later acknowledged the aptness of Wren’s scheme, where to the east of St Paul’s two streets would form a ‘Pythagorean Y’, and noted that he ‘willingly follow[ed] it in my second thoughts’; yet Evelyn hid that Y behind a new St Paul’s, whereas Wren parted the streets more dramatically in front of it. Wren’s streets were wider, and his Royal Exchange was given a prominent position along the northeast bifurcated street leading from St Paul’s; whether that was deliberate or not, it was a clear celebration of commerce. Wren also wished to reduce the size of St Paul’s and the number of city churches to nineteen from eighty-six to acknowledge their diminished congregations, which Evelyn might not have wished (though he himself brought the number down to twenty, with parish boundaries redrawn). But he would have welcomed Wren’s Baroque and geometrical urban layout and the Pantheon-like St Paul’s with a dome above porticoes.

Neither scheme for this urban development was fulfilled, not least because of some energetic jockeying in the Royal Society about whose plan would be best – there were three prominent members vying with their own plans. Oldenburg, who managed the Society’s Philosophical Transactions, saw the process as ‘still very perplex’. Evelyn’s own was marginalized when plans, which included Wren’s, were considered by the House of Commons. A survey undertaken prior to any remodelling to measure all the original foundations was conducted by Wren and Hooke, the curator of the Royal Society but later appointed surveyor of the City.7 Now there were hopes of progress. Pepys records in his Diary that Hugh May saw ‘the design of building the City doth go on apace’, but then hoped that it would not come too late to satisfy the people. The estimated costs, the ‘disputes over legal ownership, boundaries law and custom’ (Darley, John Evelyn, p. 223) caused delays. Nor was it easy to make or remake a city after the loss of thousands of buildings. Simply the availability of materials for rebuilding proved a major obstacle, for there was no question that timber was impossible and that bricks and stone would be needed. The Act for the Rebuilding of the City of London was passed by Parliament in February 1667, and a second rebuilding Act followed in 1671; the first of those specified brick. Evelyn, having written about earth and its soils, was much involved in exploring the quality of clays and he investigated the option for kilns to be established at Deptford; he and a colleague, Sir George Sylvius, sought to obtain, unsuccessfully, the sole licence for inventing new kilns for the manufacture of plaster, tiles and bricks.

Evelyn’s disappointment during the aftermath of the Fire and the work on rebuilding was clearly a setback, with his probable financial loss on the kiln scheme, and more crucially with his inability, as a prominent member of the Royal Society, to see his ideas on the rebuilding make headway. But in other respects, he could still take pleasure in work for the Society: in the donation of Henry Howard’s library to the Society, and his appreciation of Howard’s provision of rooms for the Society in Arundel House in the Strand after Gresham was made uninhabitable following the Fire. Equally, he was pleased by the successful transfer of the Arundel Marbles from the garden on the Strand to the University of Oxford and the display of their inscriptions, bas-reliefs and sculptures around the new Sheldonian Theatre. After the opening in 1683 of the Ashmolean Museum, they were installed there.

If he did not have success in planning and projecting a new London, he cast his mind back favourably to his days in Paris, when advising Pepys in 1669 on his travels through France. He insisted much on what good architecture had been achieved there, though making some positive comparisons with what was new and a-building in England. His long letter (Particular Friends, pp. 68–70) advises visits to hospitals, the Palais du Luxembourg, which he thought as ‘fine as Clarendon House’, the Louvre and the Tuilleries, the Pont Neuf that lacked the houses which so cluttered London Bridge, the Val-de-Grâce (‘your eyes will never desire to behold a more accomplished piece’), Mansart’s Maisons, where he had once taken his young wife and which, he gathers, has survived better than St Germain-en-Laye, the then as yet incomplete Collège des Quatre Nations, founded by Mazarin, and generally the uniformity of new housing. Beyond architecture, he treasures his memories of gardens outside Paris, the fortifications at Calais, ‘many rare Pictures and Collections’ and libraries.

His advices and recommendations for Pepys and his wife, whose father had been French, had perhaps been triggered while preparing yet another translation from the French, his version of Fréart’s An Idea of the Performance of Painting Demonstrated (1668), which he dedicated to Henry Howard in gratitude for the ‘never-to-be-forgotten’ generosity of gifting his grandfather’s collection of both books and marbles; he might also have been acknowledging Howard’s patronage for the gardens at Albury and help with gardens in Norwich. In his Preface he protests at the drudgery of translating (perhaps in disappointment at his failed urban involvements), but justifies it by saying that with his discussion of painting he had completed his survey of the arts, after Sculptura and Fréart’s architectural book. The title page continues Evelyn’s determination to draw parallels between ancient writers on lost paintings (the elder Pliny and Quintilian) with the work of modern painters like Nicolas Poussin; Keynes notes that one presentation copy was given to the painter Sir Peter Lely ‘from his humble servant J. Evelyn’.

But his concerns with the transference of ancient ideas to gardening at least were still consuming and he continued to urge them, even though he had presumably given up on ‘Elysium Britannicum’. Later, during the 1690s, he corresponded with William Wotton, tutor for the children at Albury, who was planning a life of Boyle, for which Evelyn plied him with information and encouragement: ‘the subject you see is fruitful, and almost inexhaustible’ (Correspondence, pp. 347–52). Wotton had already published Reflections upon Ancient and Modern Learning in 1694, and for his second edition (1697) he added a chapter ‘Of ancient and modern agriculture and gardening’. Wotton’s addition was clearly inspired by his correspondence with Evelyn, who the year before had urged him to read René Rapin’s Hororum libri (which Evelyn’s son had translated, and a copy of which was lent to Wotton) as a source on ancient ideas and practice:

Concerning the gardening and husbandry of the ancients, which is the inquiry (especially of the first), that it had certainly nothing approaching the elegancy of the present age, Rapinis (whom I send you) will abundantly satisfy you [here he cites the relevant sections of the fourth book]. What they call their gardens were only spacious plots of ground planted with plants and other shady trees in walks, and built about with porticoes, xysti, and noble ranges of pillars, adorned with statues, fountains, piscariae, avaraies, &c . . . Pliny indeed enumerates a world of vulgar plants and olitories, but they fall infinitely short of our physic gardens, books and herbals, every day augmented by our sedulous botanists, and brought to us from all quarters of the world. (Correspondence, pp. 363–4)

He also advised Wotton to read the Huguenot gardenist and ceramicist Bernard Palissy, whose Recepte véritable of 1563 contained a long description of how to construct a hillside garden;8 this suggests how much Evelyn was still attuned to early modern garden ideas from France. But in this case it was perhaps less surprising, as Palissy had projected his garden as a physical representation and celebration of Psalm 124 (as a Protestant he wanted the Bible accessible in the vernacular and as authorized text), and Evelyn would have been keen to see such a modern, as opposed to a pagan, garden constructed; yet it is hard to envisage Evelyn wishing to make garden references explicitly to the scriptures in seventeenth-century England.

Wotton was far less cagey than his correspondent, and in Reflections he credits Sylva with containing things that the ‘ancients were strangers to’ and that it ‘out-does all that Theophrastus and Pliny have left us on that subject’. Similarly, the ancients fell ‘far short of the gardens and villas of the princes and great men of the present age’ (p. 300), and the moderns excel in plant variety, gravel walks and ‘spacious grassplots, edged with beautiful borders’. Evelyn agreed in a letter of 28 October 1696 that modern gardens excelled in ‘elegancy’ of construction and ‘dials’. Nor surprisingly at that date, when his piety had been much exercised, does he resist supplanting pagan ornaments in gardens with Christian and philosophical imagery: the ‘obscene Priapus’, the ‘lewd strumpet’ Flora would give way to ‘sacred stories’ and ‘representations of great and virtuous examples’, so maybe Palissy had an effect.

To Sir Thomas Browne in 1660 he had written of the need to ‘redeem that time that has been lost’ during the Interregnum (Diary, IV.275) by drawing upon ‘all the august designs and stories . . . either of ancient or modern times’. On the progress of gardening from its ancient beginnings until the modern and scientific age, he tries to be even-handed; yet the central ambition of ‘Elysium Britannicum’ is to ‘refine upon what has been said’ (EB, 253), with that refinement being essentially a modern enterprise. Much later, in Acetaria (1699), he noted that the ‘artist gardener’ takes many ages for his skills to be perfected, which inevitably values the latest perfection. For gardens are always alive, flourishing on the earth, and therefore above all modern. If a writer like Sir William Temple (echoed later by Alexander Pope) could argue that the garden of Alcinous in Homer’s Odyssey proved all the necessary rules for a fine garden, which Evelyn’s letter to Wotton about Pliny (quoted above) seems to reject, then those necessary rules must depend upon their translation into modern forms and uses. All good translations require no diminution nor declension of the original, yet a clear sense that the translated ‘text’ was clearly of the moment: hence Oldham’s determination to make Horace ‘speak, as if here living and writing now’; hence Evelyn’s 1667 reworking of Albury.