Chapter 3

Materials and Methods of Classification

The huge wealth of material available for the textual criticism of the NT is both a blessing and a curse. Although the number varies depending upon how they are counted, by one count there are over seventy-two hundred Greek manuscripts of various sizes and shapes representing different portions of the NT, in addition to hundreds of copies of various ancient versions or translations, and quotations of the NT in the early church fathers (see ch. 4). NT manuscripts range from the complete or close to complete major codices, such as Codex Sinaiticus or Codex Vaticanus, to much more fragmentary materials such as P. Vindob. G 42417 (𝔓116),1 a recently discovered and published NT papyrus manuscript containing a few verses of Hebrews (Heb 2:9-11 on one side; 3:3-6 on the other). The original NT manuscripts unfortunately no longer exist. In their place, we have copies of copies made over the course of hundreds of years, as scribes copied these by hand and passed them down to others. The inevitable result of this process of copying and textual transmission is that a number of changes have been introduced either intentionally or unintentionally into the manuscripts. Some of the changes were made intentionally in order to correct or improve a manuscript (or so a scribe thought), while others were made unintentionally through carelessness or a slip of the pen. As a result, despite the large number, no two NT manuscripts are identical in all aspects.

1. Books and Literacy in the First Century

In the Greco-Roman world in which the NT was written, there was a traditional emphasis upon orality (communication through spoken rather than written media), such that the major ancient authors wrote for oral performance in such media as Greek epic and tragedy. However, with the growth of the Roman Empire there arose a need for record keeping that led to a widespread scribal culture that developed into a full-blown literary culture. Thus Rosalind Thomas distinguishes between documents and records.2 All sorts of documents (e.g., business transaction, receipts) were written for different purposes. However, there is a transition that takes place when one recognizes that written documents may become records of persons, possessions, or other things. With this recognition there comes a certain power in literacy, to the point of developing systematized record keeping. This is one of the hallmarks of the Roman Empire, especially as evidenced in the papyri remains from Egypt (see the next section). The confluence of record keeping and power can be clearly seen in the tax records that were completed by the Romans every seven years up to A.D. 11/12 and then every fourteen years from A.D. 19/20 on. Even if an ancient person was illiterate, he or she was not far removed from literate culture in the need to use and have access to written documents. The power of record keeping included the power to tax and the power to control the people. In the Jewish world of the time, which functioned within the larger Greco-Roman world, there was a similar phenomenon regarding the interplay of orality and literacy. Birger Gerhardsson notes the creative and dynamic role that oral tradition played in the rise of Judaism. He also notes that early on, a number of centuries before the Christian era, written tradition also began to play an important part in Judaism. Gerhardsson shows that the written Torah, what we would equate with our OT, was complemented by the oral Torah, which constitutes the oral interpretation that goes hand in hand with it.3

Many students of the NT do not fully realize, however, the type of book culture that was already flourishing in the first century A.D. Such a book culture is often dismissed on the basis of a purported lack of means of copying, the high cost of materials, and widespread illiteracy. The disparagement of writing and the book culture is, in some ways, an unfounded consequence of a way of thinking that draws a firm disjunction between orality and literacy. In other words, because the culture is posited as oral, the claim is that there must not be significant written sources. In fact, the standard assumptions regarding the lack of means of copying, expensive materials, and widespread illiteracy do not hold up in light of the evidence.

The copying and producing of handwritten copies of books was not as big an obstacle in the ancient world as many have assumed. How else do we account for such factors as Galen, a second-century A.D. doctor, wandering through a market and seeing books for sale, and his checking and seeing that some of those for sale were attributed to him and he knew that he had not written them? In other words, there was enough of a market for books that it made forgery a desirable option for some (clearly not for Galen, who was incensed). Similarly, the literary tradition associated with the ancient Greek orator Lysias is that a significant number of the works attributed to him even in ancient times were known to be forgeries, a problem that has kept scholars busy for years. Likewise, the Qumran community, though always a relatively small community living in isolation, was responsible for creating a significantly large number of books. There were also a number of large, well-known libraries, such as the ones at Alexandria and Ephesus, among others. There were a number of small private libraries as well, which may have been more important to the book culture than the larger libraries. In other words, books appear to have been so plentiful by the first century A.D. that the Latin author Seneca goes so far as to denounce what he sees as the ostentatious accumulation of books. Without minimizing the importance of orality — and that the major means of “publication” was in terms of oral performance, such as orations, the reading of poetry, lectures delivered in public, and theater — we must also recognize that there was a parallel book culture that was large and significant. There was no publishing industry as we would know it today, but there were means of getting books produced nevertheless.

The cost of book production was relatively cheap, at least cheaper than is often assumed. Papyrus, the paper of the ancient world, was widely available and so the cost was not high (on papyrus, see below). As Thomas Skeat, the papyrologist from the British Museum, has argued, papyrus was affordable in the ancient world, as indicated by statements by the ancients and the bountiful evidence of discarded papyrus discovered throughout Egypt — very few of which were ever reused, even if they were blank on one side.4 The cost of getting a book copied was not exorbitant, ranging from two to four drachmas, which is the equivalent of anywhere from one to six days’ wages. Frederic Kenyon notes that as early as the fourth century B.C. there was a “considerable quantity” of “cheap and easily accessible” books to be found in Athens, which shows that a reading culture was growing even during that time.5 In Hellenistic Egypt (300 B.C.–A.D. 300), as is indicated by the documentary and especially the literary finds, there were numerous books available, to the point that “Greek literature was widely current among the ordinary Graeco-Roman population,” and this was a likely pattern throughout the Hellenistic world.6

That these books were accessible to a wide range of people is indicated by the fact that the most common literary author found in the papyri is the epic poet Homer, the major author read in the ancient Greek grammar school. Access to these books was gained through a variety of means. There was what amounts to what Loveday Alexander has called a commercial book trade. Alexander notes that the main motivation of authors to publish in ancient times — perhaps not too unlike modern times — was fame, not necessarily money. Hence there were not the same kinds of restrictions on access as we have created today. Authors themselves would probably have been involved in “publication” of their books.7 Raymond Starr notes that the author would have written a rough draft, and then had it reviewed by others, such as slaves or friends. Once a final form of the text was formulated, it was circulated to a wider group of friends, before being more widely disseminated. As a result, perhaps the easiest way to secure a book was to borrow a copy from a friend and either have a slave or scribe copy it, or make one’s own copy.8 As Alexander notes, Aristotle, Cicero, Galen, and Marcus Cicero the younger all seem to have been part of this process.9

This transmission process is undoubtedly how many of the first copies of the NT books would have been made, as churches loaned out and allowed copies to be made of early Christian letters or Gospels in their possession. Harry Gamble has shown that there were associations of people connected with book production, so that those who were interested in a particular type of literature would produce and share these types of books.10 This perhaps accounts for an episode that the Jewish historian Josephus records, in which a rebel in Galilee confronted him with “a copy of the law of Moses in his hands” as he tried to work the crowd (Josephus, Life 134). This sharing of books would have included those who were interested in not only the Greek text of the Bible (i.e., the Old Greek or LXX) but also Gospel texts and Christian letters, for example, early Christian congregations. Thus, as the Christian community expanded, more copies of NT books were demanded by individual local congregations and so copies were borrowed from other churches and reproduced. The rapid spread of Christianity in the ancient world, therefore, accounts for the rapid production of NT books represented by the abundant number of manuscripts currently available (at least when compared to other literary and historical works in antiquity — see below on Statistics for New Testament Manuscripts).

As Christianity became more and more popular, a large part of the production of NT books was eventually turned over to professional scribes so that by the fourth century the NT had begun to be copied primarily in various scriptoria (plural of scriptorium), places of professional book manufacture. In a scriptorium, an original or exemplar (but not necessarily the original written by the author) was read aloud and copied down by scribes. Later, during the Byzantine period (roughly A.D. 867-1204), the NT was copied by individual monks in monasteries, where the documents were copied instead of being written down on the basis of verbal dictation.

Finally, we return to the issue of literacy. The classicist William Harris’s well-known monograph on this topic was not the first to address the issue, but it was the first to study systematically the historical, documentary, and literary evidence, and then to attempt to quantify the literacy of the ancient world.11 His work distanced him from those who had emphasized the oral culture of the ancient Greeks. Some rejected his findings by claiming that he had overestimated the influence and capability of writing, but the majority found that he had underestimated the impact of literary culture, at least in the Greco-Roman context. Even if his statistics are accurate and are not underestimated — that overall 20-30 percent of men in the Roman Empire were literate, and that 10-15 percent of women were, for an overall literacy rate of no more than 15 percent — he seems to have neglected the fact that even those who were illiterate came into regular and widespread contact with literate culture. For example, a person illiterate in Greek might need to have a contract written out, and so would of necessity be a part of literate culture by virtue of needing to have this document prepared, and would need to deal with the consequences of it, such as a document sent in return. The classicist Alan Bowman goes so far as to state that a “large proportion” of the 80 percent who may have been formally illiterate were to some degree participants in literate culture.12 Further, there are far more ancient documents still to be deciphered, as well as a number that were destroyed — all evidence of literacy that needs to be taken into account.13 The classicist Keith Hopkins notes that, according to Harris’s figures, there were over two million adult men in the Roman Empire who could read, and that this large number would have exerted a significant influence upon the society as a whole.14 Finally, Catherine Hezser has shown that levels of literacy among Palestinians were far higher than the average of the Roman Empire,15 evidence quite relevant to the study of early Christianity. This means that there would probably have been literate people in most early Christian churches, encouraging the circulation of early Christian literature. Nevertheless, since there was assuredly a large contingent of illiterate people among the congregations as well, letters and narratives were probably still most often read aloud.

2. Writing Materials and the Forms of Ancient Books

Prior to the discovery and widespread utilization of the stalk of the papyrus plant as a writing material in the ancient Mediterranean world, wax tablets were used for the purposes of writing, in which a thin pointed stick called a stylus was used to impress letters upon the wax surface. By the time of the early Christian era, however, records and documents were written primarily on papyrus (an ancient form of paper made from the stalk of the papyrus plant) or, somewhat later, parchment (an ancient form of writing material made from prepared animal skins). Papyrus or parchment was usually used in the form of a scroll (in which individual pieces were connected together sequentially to form a roll upon which written material was placed on one side) or a codex (plural = codices or codexes) (an ancient book or leaf-bound form on which writing was done on both sides). The ink that was used depended upon the type of material in use. While a carbon-based solution, composed of charcoal and lampblack or water, was most often used to write on papyrus, Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman note that since “carbon inks do not stick well to parchment, another kind was developed, using oak galls and ferrous sulfate, known also as ‘copperas.’ ”16 Similarly, due to texture and firmness, pens made out of reed were best suited for writing upon papyrus, whereas quill or feather pens were better for writing on parchment.

a. Papyrus

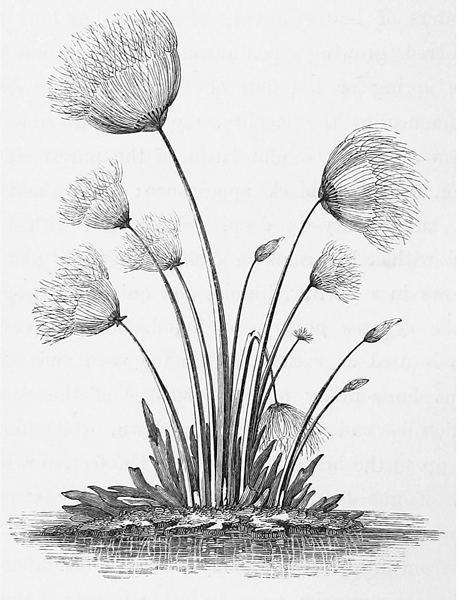

The papyrus plant (see Fig. 3.1 on p. 40) was most abundant in the Nile Delta and therefore was produced primarily in Egypt, although it was known to grow in many other places in the Mediterranean world as well. In ancient times, the plant grew to between six and twelve feet tall, with a thin stem and a grassy blossom at the top. To convert the plant into flattened papyrus sheets that would accommodate writing required a number of steps. The first step was to remove the outer layer of skin. The stem was then divided into a number of vertical sections and cut into thin strips. In the first century, during the time of the naturalist Pliny the Elder, who wrote about papyrus, the strips were pressed together and held in place by the natural sap of the plant (Nat. 13.20-26). By at least the third century, during the reign of the Roman emperor Aurelian, glue began to be used in the manufacturing process (Nat. 13.26). However, the older process using the sap of the papyrus plant as adhesive turned out to be superior in terms of producing a more durable, longer lasting material. The result of the procedure was a textured, often brittle paperlike material that could be used as a surface for writing with ink. The John Rylands papyrus fragment of John’s Gospel (𝔓52), the earliest NT fragment, provides an excellent example of what an early NT papyrus looked like (see Fig. 3.2). The oldest witnesses to the NT are written on papyrus since parchment was not heavily utilized in writing until shortly after the NT period. Papyrus sheets would have been the writing material that the NT authors used to write their letters, compose their Gospels, and record their visions. This is confirmed by 2 John 12, where the word usually translated “paper” (χάρτης) refers to a piece of papyrus. Most of the NT papyri come from Egypt, with a few from Palestine, since the dry climate conditions especially of Egypt have allowed for their preservation — papyri quickly deteriorate in more humid climates, such as the northern Mediterranean.

Figure 3.1. A papyrus plant

(Wikimedia Commons)

Figure 3.2. P52, a papyrus fragment from the Gospel of John

(The John Rylands University Library, The University of Manchester, Manchester, England. Reproduced by courtesy of the University Librarian and Director)

Even in Egypt, little is known regarding the geographical origin of NT papyri, but we do know that a number of papyri were discarded in the rubbish heaps of the Fayum region and of the ancient city of Oxyrhynchus. Oxyrhynchus is a particularly important site where a number of NT and other early Christian papyri have been identified — papyri found at this site are indicated by the abbreviation P. (which stands for papyrus) Oxy. (which stands for Oxyrhynchus) prior to the papyrus number (e.g., P.Oxy. 3523 in the Oxyrhynchus collection, but within the NT papyri designated as 𝔓90). Oxyrhynchus was known for having a vibrant Christian community and book culture, as the papyri found there clearly attest. Therefore, papyri from Oxyrhynchus have been useful not only in textual criticism but also in understanding contemporary Greek language and literature and various historical contexts for the transmission of the NT. Publication of the huge number of Oxyrhynchus papyri is an ongoing process, so unfortunately a large number of these papyri remain unpublished and have not yet been subjected to scrutiny by the academic community.

b. Parchment

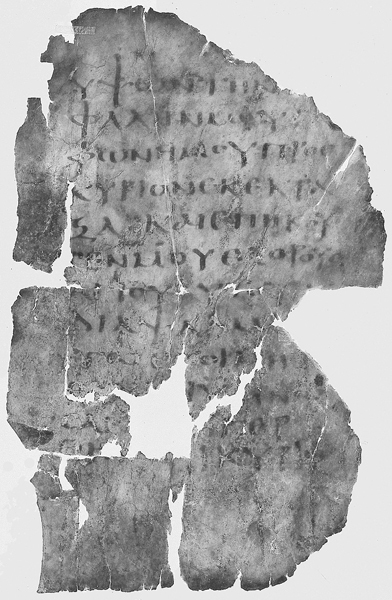

The limited availability of the papyrus plant in other areas of the ancient Mediterranean world — being mostly, but not entirely, restricted to Egypt — meant other writing materials had to be used in the process of serious book production in locations where the papyrus plant did not grow. This led to the production of parchment or vellum, which employed treated animal skins rather than the papyrus plant (see Fig. 3.3). Pliny accredits the rise of the use of parchment outside Egypt to the decision of King Eumenes II (197-159 B.C.) of Pergamum (a city in western Asia Minor, now Turkey) to build a library comparable to the one in Alexandria. Ptolemy I, the king of Egypt at the time, was not happy with this plan and so he put an embargo on the export of papyrus in order to discourage Eumenes’ efforts, forcing Eumenes to develop a leather-based writing material now known as parchment (Pliny, Nat. 13.21).17 Regardless of the historical merits of the story, Pergamum was certainly famous for its parchment production, which became the most significant writing material in the ancient world by the third century — and for obvious reasons. In addition to being able to be produced anywhere where there were animals, parchment was more durable, longer lasting, and easier to bind than papyrus and could withstand various climate conditions. The texture was soft, and, in some cases, traces of animal hair can still be found on the external side. The majority of significant NT manuscripts are recorded on parchment. The two most significant codices, Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus (both from the fourth century A.D.), are written on parchment pages bound in book form. Although parchment is found in the scroll form also (e.g., some of the Dead Sea Scrolls), the codex gained popularity around the same time that parchment began to be the most common material used for writing in the ancient world. So the majority of the parchment NT manuscripts come in the form of codices.

Figure 3.3. A fragment of a leaf of a parchment codex showing Psalm 3:4-8

(P.Mich.inv. 1573, recto; courtesy of the Papyrology Collection, University of Michigan Library)

c. Scroll

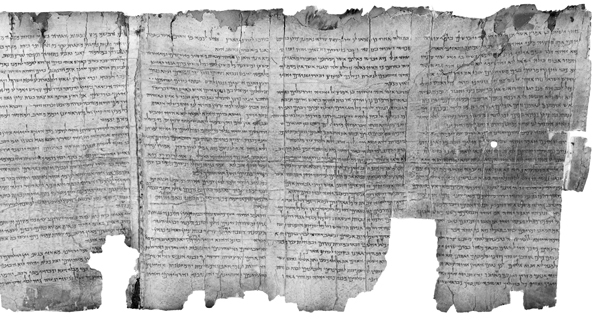

The NT authors and earliest Christian churches would have used the papyrus scroll to write and read their sacred literature in its earliest form. This was the typical format for the publication of literary works in the Greco-Roman world of the turn of the millennia. One side of the papyrus was used for writing, and the other side was left blank (but cf. Rev 5:1). Scrolls had a number of disadvantages, however. They were inconvenient for referencing passages within a particular work because readers would have to keep unrolling the scroll until they found the desired place in the work. It was difficult to handle these rolls, especially if a literary text was particularly long. This limitation of length also discouraged authors from writing longer works; but, if they did, they usually had to compose the work in two or more volumes (e.g., Luke-Acts). This limitation on length may have led NT authors to compose anthologies or readers on a single scroll, containing a number of key passages on selected topics from a number of different literary works, instead of only a single continuous literary work (these are sometimes called testimonia). The production and use of testimonia was a common practice in the Greco-Roman schools as well as at Qumran. Such testimonia may have been used by someone like Paul who, in his travels, could not afford to carry around a bag full of cumbersome scrolls (no single scroll could contain the entire Bible or OT), but needed to have quick and easy access to Scripture as he composed his letters on the go. The Dead Sea scroll pictured in Figure 3.4 gives an idea of how an ancient scroll would have looked.

Figure 3.4. A portion of the Great Isaiah Scroll

(Google Art Project / Wikimedia Commons)

d. Codex

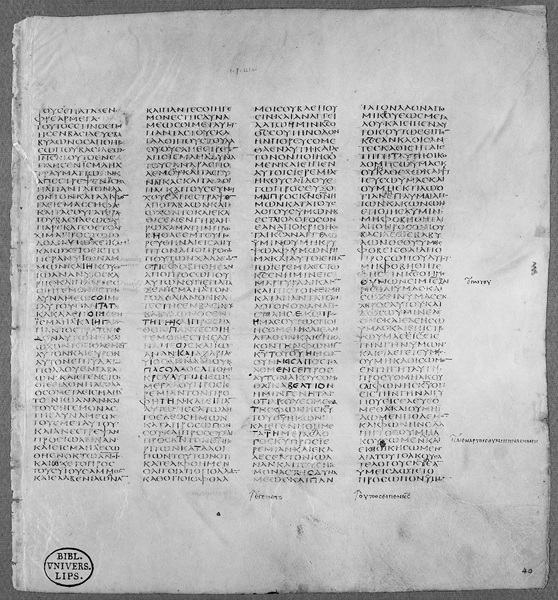

Due to the inconvenience of the scroll format, early Christians pioneered the invention of the codex, the first step toward the production of the modern book. The codex facilitated greater ease in referencing passages, allowed for writing on both sides, and allowed for various groups of books (e.g., the Gospels, Paul’s Letters) to be collected in one volume. The codex was formed by laying numerous pieces of papyrus or parchment on top of one another, folding them in the center, and then sewing them together on the fold. This, then, formed a quire, and as many quires as were desired to make the book were then created and sewn together. The picture of Codex Sinaiticus (Fig. 3.5) shows what an ancient codex looked like. There are four columns on each page — although the number of columns may vary — with a fold down the middle of the volume, where the quires have been made and sewn together. Although we know that the earliest NT documents were written on scrolls, the earliest manuscript we currently have (𝔓52, the John Rylands papyrus, Fig. 3.2 on p. 41) is a page from a codex.

Figure 3.5. A folio from Codex Sinaiticus showing a portion of Jeremiah

(Q49, fol. 5r; Jer. 48:9–49:15. Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig, Cod.gr.1)

3. Writing Styles

Philip Comfort and David Barrett conveniently list four types of handwriting typically identified by paleographers (those who study ancient writing and inscriptions):

- 1. Common: the work of a semiliterate writer who is untrained in making documents. This handwriting usually displays an inelegant cursive.

- 2. Documentary: the work of a literate writer who has had experience in preparing documents. This has also been called “chancery handwriting” (prominent in the period A.D. 200–225). It was used by official scribes in public administration.

- 3. Reformed documentary: the work of a literate writer who had experience in preparing documents and in copying works of literature. Often, this hand attempts to imitate the work of a professional but does not fully achieve the professional look.

- 4. Professional: the work of a professional scribe. These writings display the craftsmanship of what is commonly called a “book hand” or “literary hand” and leave telltale marks of professionalism — such as stichoi markings (the tallying of the number of lines, according to which a professional scribe would be paid), as are found in 𝔓46.18

The most important indicator of the date of ancient NT manuscripts is the kind of hand or script that the scribe used. The styles mentioned by Comfort and Barrett are found in varying degrees among early majuscule and later minuscule Greek hands. The earliest and most significant NT manuscripts are written in the majuscule hand. Majuscule (meaning “large”) is a square hand with large letters that employs no spacing between the words and is only found in the earliest codices (usually not after the seventh century). Parker defines the majuscule hand as “a formal bookhand of a fair size in which almost all of the letters are written between two imaginary lines”19 — all of the Greek manuscripts pictured above employ a majuscule hand, but the styles vary. This hand and the relevant manuscripts are sometimes referred to as uncials. Recent scholarly consensus, however, rejects this designation as referring only to a particular Latin majuscule and having little relevance to the Greek hand relevant to NT textual criticism. Paleographers typically discuss a number of other types of majuscule hand. The majority of NT manuscripts are written in what is referred to as a biblical majuscule hand — which is not, incidentally, limited to biblical manuscripts — characterized by straight upright letters, clearly distinct from one another, not running together as with a cursive hand. The Roman majuscule is an earlier hand distinguished by an alternation between thick and thin pen strokes as we see in 𝔓46, for example (cited above). There is also a more decorative, rounded majuscule, most popular from 100 B.C. to A.D. 100, but represented among some biblical papyri (e.g., 𝔓32, 𝔓66, and 𝔓90). Other distinct majuscule hands arose based upon the tendencies of the individual scribes. The hand employed in Codex Bezae, for example, seems to suggest that the scribe had a greater familiarity with Latin characters than Greek characters.20 While Greek accents are attested as early as the third century B.C., they are only employed sporadically in manuscripts written in a majuscule hand. NT authors would have used something very close to the majuscule hand that we find in the earliest NT manuscripts, although handwriting styles would have varied — depending on whether a scribe was employed and the level of the scribe’s competency.

Later manuscripts are written in a minuscule (meaning “small”) hand (arising during the seventh and eighth centuries), characterized by smaller, clearer letters with the consistent use of spaces, breathing marks, various combined letters, and accents. This style is much more comparable to the modern Greek fonts used in printed editions, such as Nestle-Aland27/28 or UBSGNT4/5. The minuscule tradition is distinctively characterized by its close relationship to the Byzantine textual tradition (see ch. 4). The earliest minuscule manuscript, the Uspenski Gospels (A.D. 835), is in a fully developed book hand in the standardized Koine of the Byzantine period. The minuscule tradition of NT manuscripts, though late, does provide important confirmatory material for textual criticism when it supports or contradicts certain isolated readings. There are also far more minuscule manuscripts than there are majuscules (only about 10 percent of extant manuscripts are written in the majuscule hand), making it much easier to trace the (geographical) origin of differences within various traditions that go back to the earlier majuscule manuscript tradition.

4. Scribal Additions, Alterations, and Aids

Early manuscripts of the NT contain a number of scribal additions, alterations, and aids for readers. These range from notes in the margins for various purposes to additions/changes for clarity to abbreviated sacred words. Scribes viewed these changes as helps for future scribes and readers of the text.

In addition to pioneering the codex, the early Christian community also introduced a set of abbreviations for sacred words known as the nomina sacra. Larry Hurtado states, “The nomina sacra are so familiar a feature of Christian manuscripts that papyrologists [scholars who study papyri] often take the presence of these forms as sufficient to identify even a fragment of a manuscript as indicating its probable Christian provenance.”21 For example, instead of writing out the Greek word for “Lord” (κύριος) in full, Christian scribes would use the contracted form ΚΣ. Similarly, for θεός (“God”), ΘΣ was used, and for Ἰερουσαλήμ (“Jerusalem”), ΙΛΗΜ or ΙΜ was employed. The use of these distinctively Christian forms has aided scholars in locating Christian or Jewish manuscripts when sorting through previously unclassified Greek materials.

A form of annotations found in a number of manuscripts is the result of corrections made by a διορθωτής, a specially trained scribe in the scriptorium who would check individual manuscripts for accuracy, typically noting his changes by a distinct form of handwriting or by using a different shade of ink.

The scribes that copied Codex Sinaiticus apparently had a conception of paragraph divisions, often initiating what they perceived to be the beginning of a unit with a larger letter, often the Κ in καί (“and”) or another conjunction. In Mark’s Gospel, for example, 310 units are marked by a large initial letter and/or a shorter preceding line.

A number of aids were also introduced by scribes to assist in the public reading of Scripture. These include the insertion of chapter divisions and titles, scholia (brief commentary, usually in the side margin), references to parallel Gospel passages, various forms of introduction to particular books (e.g., information about the author), explanations of difficult words or phrases (usually in the side margins), additional punctuation, superscriptions indicating the title or author of a book, decorative ornamentation (especially in later manuscripts), and various liturgical aids (e.g., musical notes, marking of units for reading in worship service, usually in the side margins).

Not all changes introduced by scribes were intentional, however. The tedious nature of the scribal process coupled with the challenge of recording oral dictation (if the manuscript was produced in a scriptorium) or even of accurately copying a manuscript often resulted in a number of unintentional changes from the text being copied. These will be taken up in some detail in chapter 9, dealing with internal evidence.

5. Methods of Classifying Materials

Unfortunately, the current method of classifying NT manuscripts is fairly inconsistent — a price that came with the slow development of the discipline, the gradual discovery of new materials that needed to be classified, and the lack of standardization early on. Some manuscripts are classified according to script. Others are classified according to the material they are written on. Still others are classified according to content. Manuscripts written in the majuscule or minuscule hand are referred to as majuscule and minuscule manuscripts, as long as they are written on parchment (although this is not an issue for minuscule manuscripts, which are not written on papyrus). Manuscripts written on papyri, however, are classified as papyri manuscripts rather than according to the hand they are written in. A final, later group of sources for NT textual criticism not previously discussed are lectionaries. These are classified according to content (thus they are not treated above under “Writing Materials”). Lectionaries are collections of selected passages designed for use in Christian worship services, dating from ancient times up through the Reformation period. Passages are arranged in a distinct order and frequently introduced by liturgical notes, and various modifications are often made to the text in order to account for the occurrence of the passage in isolation from its original context.

6. Statistics for New Testament Manuscripts

An official list of Greek manuscripts, classified according to the categories defined above, includes the following numbers (although this does not indicate that all of the manuscripts are separate or even now in existence, and this number will have increased by the time of publication, as new manuscripts are constantly being discovered and catalogued):22

- Papyri: 134

- Majuscule Manuscripts: 323

- Minuscule Manuscripts: 2,931

- Lectionaries: 2,465

- Total: 5,853

When compared with other works of antiquity, the NT has far greater (numerical) and earlier documentation than any other book. Most of the available works of antiquity have only a few manuscripts that attest to their existence, and these are typically much later than their original date of composition, so that it is not uncommon for the earliest manuscript to be dated over nine hundred years after the original composition. The classicist and biblical scholar F. F. Bruce has conveniently catalogued this data.23 The chart below is based upon his calculations.

| Book | Date | Number of MSS | Oldest Copy |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Caesar’s Gallic Wars |

58-50 B.C. |

8-9 |

A.D. 800-808 |

|

Livy’s Roman History |

59 B.C.–A.D. 17 |

20 fragments |

1 from the 4th century |

|

Tacitus’s Histories/Annals |

A.D. 100 |

2 |

9th century A.D. |

|

Tacitus’s Minor Works |

A.D. 100 |

1 |

10th century A.D. |

|

Thucydides’ History |

460-400 B.C. |

8 |

A.D. 900 |

|

Herodotus’s History |

488-428 B.C. |

8 |

A.D. 900 |

Therefore, as Helmut Koester observes,

Classical authors are often represented by but one surviving manuscript; if there are half a dozen or more, one can speak of a rather advantageous situation for reconstructing the text. But there are nearly five thousand [!] manuscripts of the NT in Greek…. The only surviving manuscripts of classical authors often come from the Middle Ages, but the manuscript tradition of the NT begins as early as the end of II CE; it is therefore separated by only a century or so from the time at which the autographs were written. Thus it seems that NT textual criticism possesses a base which is far more advantageous than that for the textual criticism of classical authors.24

Fortunately, the NT textual critic has the unique privilege of such a rich documentation of the textual transmission of the NT, but this also results in certain complexities since there are so many documents to compare. It then becomes the duty of the textual critic to assess the available manuscripts and weigh the variant readings in order to determine which reading most likely reflects the original.

7. Summary

In this chapter we have examined the material for writing in the first century, literacy, various writing styles, scribal editorial tendencies, methods for classifying NT manuscripts, and the statistics for NT manuscripts and other works from classical antiquity. Now that we have briefly examined the materials for textual criticism, it is appropriate to turn to consider more specifically the significant witnesses to the text of the NT.

Key Terminology

- scriptorium/scriptoria

- exemplar

- papyrus

- parchment

- scroll

- codex

- Oxyrhynchus (P.Oxy.)

- vellum

- paleographers

- majuscule

- uncial

- minuscule

- nomina sacra

- lectionaries

Bibliography

Aland, Barbara, and Klaus Wachtel. “The Greek Minuscule Manuscripts of the New Testament.” Pages 69-91 in The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis. 2nd ed. Ed. Bart D. Ehrman and Michael W. Holmes. NTTSD 42. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Alexander, Loveday. “Ancient Book Production and the Circulation of the Gospels.” Pages 71-111 in The Gospel for All Christians: Rethinking the Gospel Audiences. Ed. Richard Bauckham. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998.

Beard, Mary, ed. Literacy in the Roman World. JRASup 3. Ann Arbor: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1991.

Bowman, A. K. “Literacy in the Roman Empire: Mass and Mode.” Pages 119-31 in Literacy in the Roman World. Ed. Mary Beard. JRASup 3. Ann Arbor: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1991.

Easterling, P. E., and B. M. W. Knox. “Books and Readers in the Greek World.” Pages 1-41 in Greek Literature. Vol. 1 of The Cambridge History of Classical Literature. Ed. P. E. Easterling and B. M. W. Knox. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Ehrman, Bart D., and Michael W. Holmes, eds. The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis. NTTSD 42. 2nd ed. Ed. Bart D. Ehrman and Michael W. Holmes. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Ellis, E. Earle. The Making of the New Testament Documents. Leiden: Brill, 1999.

Epp, Eldon Jay. “The Papyrus Manuscripts of the New Testament.” Pages 3-21 in The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis. 2nd ed. Ed. Bart D. Ehrman and Michael W. Holmes. NTTSD 42. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Gamble, Harry Y. Books and Readers in the Early Church: A History of Early Christian Texts. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Harris, William V. Ancient Literacy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Havelock, Eric. The Literate Revolution in Greece and Its Cultural Consequences. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982.

———. The Muse Learns to Write: Reflection on Orality and Literacy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

Hezser, Catherine. Jewish Literacy in Roman Palestine. TSAJ 81. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2001.

Hopkins, Keith. “Conquest by Book.” Pages 133-58 in Literacy in the Roman World. Ed. Mary Beard. JRASup 3. Ann Arbor: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1991.

Hurtado, Larry W. The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006.

Kenyon, Frederic G. Books and Readers in Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932.

Metzger, Bruce M. “Literary Forgeries and Canonical Pseudepigrapha.” JBL 91 (1972): 3-24.

———. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. 4th ed. Rev. Bart D. Ehrman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Millard, Alan. Reading and Writing in the Time of Jesus. Biblical Seminar 69. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000.

Osburn, Carroll D. “The Greek Lectionaries of the New Testament.” Pages 93-113 in The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis. 2nd ed. Ed. Bart D. Ehrman and Michael W. Holmes. NTTSD 42. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Porter, Stanley E. “Textual Criticism.” Pages 1210-14 in Dictionary of New Testament Background. Ed. Craig A. Evans and Stanley E. Porter. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000.

Porter, Stanley E., and Andrew W. Pitts. “Paul and His Bible: His Education and Access to the Scriptures of Israel.” JGRChJ 4 (2008): 9-41.

Rappoport, S. History of Egypt: From 330 B.C. to the Present Time. Vol. 11. London: Grolier Society, 1904.

Skeat, T. C. “Was Papyrus Regarded as ‘Cheap’ or ‘Expensive’ in the Ancient World?” Aeg 75 (1995): 75-93.

Starr, Raymond J. “The Circulation of Literary Texts in the Roman World.” CQ 37 (1989): 313-23.

Thomas, Rosalind. Oral Tradition and Written Record in Classical Athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

———. Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

1. Every NT manuscript has both its identification according to the collection in which it is held, and its designation in terms of the scheme used to identify all NT manuscripts, sometimes referred to as a Gregory-Aland identification (the two most important scholars who developed this scheme and classified manuscripts were Caspar René Gregory and Kurt Aland). In the example above, “P.Vindob. G” means that this is a papyrus in the Vindobonensis (Vienna) collection in Greek. It is known by the Gregory-Aland identification as 𝔓116. We further discuss this system below and in chapter 4.

2. Rosalind Thomas, Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 132-44.

3. Birger Gerhardsson, Memory and Manuscript: Oral Tradition and Written Transmission in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity; with, Tradition and Transmission in Early Christianity (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 19-32.

4. T. C. Skeat, “Was Papyrus Regarded as ‘Cheap’ or ‘Expensive’ in the Ancient World?” Aeg 75 (1995): 75-93.

5. F. G. Kenyon, Books and Readers in Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford: Clarendon, 1932), 24.

6. Ibid., 34, 36.

7. Loveday Alexander, “Ancient Book Production and the Circulation of the Gospels,” in The Gospel for All Christians: Rethinking the Gospel Audiences (ed. Richard Bauckham; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 71-111.

8. Raymond J. Starr, “The Circulation of Literary Texts in the Roman World,” CQ 37 (1989): 313-23.

9. Alexander, “Ancient Book Production,” e.g., 88-89.

10. Harry Y. Gamble, Books and Readers in the Early Church: A History of Early Christian Texts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 8-10.

11. William V. Harris, Ancient Literacy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991), 267.

12. A. K. Bowman, “Literacy in the Roman Empire: Mass and Mode,” in Literacy in the Roman World (ed. Mary Beard; JRASup 3; Ann Arbor: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1991), 119-31.

13. Ibid., 122; see also 121.

14. Keith Hopkins, “Conquest by Book,” in Literacy in the Roman World, ed. Beard, 133-58.

15. Catherine Hezser, Jewish Literacy in Roman Palestine (TSAJ 81; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010).

16. Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration (4th ed. rev. Bart D. Ehrmann; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 10.

17. For another ancient account, see Let. Aris. 9-12.

18. Philip W. Comfort and David P. Barrett, The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House, 2001), 24.

19. David C. Parker, “The Majuscule Manuscripts of the New Testament,” in The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis (2nd ed.; ed. Bart D. Ehrman and Michael W. Holmes; NTTSD 42; Leiden: Brill, 2013), 41.

20. Ibid., 53.

21. Larry W. Hurtado, The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006), 96.

22. An up-to-date “official” listing is kept at the University of Münster Institute for New Testament Textual Research (http://www.uni-muenster.de/INTF).

23. F. F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? (6th ed.; 1981; repr. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988), 11.

24. Helmut Koester, Introduction to the New Testament, vol. 2: History and Literature of Early Christianity (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1982), 16-17.