The cheetah is backed into a conservation corner. Taken alone, neither protected regions nor the much more extensive areas surrounding them are presently sufficient to conserve the cheetah. For the species to survive the next century, people will have to embrace strategies that are tailor-made to the sort of land-use where cheetahs are found. Cheetahs inside national parks and reserves can only survive where such sanctuaries are welcomed by surrounding communities. Equally, cheetahs outside parks are doomed unless people choose a lifestyle in which our two species can coexist. Humans are undoubtedly the cheetah’s greatest threat, but we also hold the only solution to its survival.

TOP CHEETAH SPOTS

The following list includes some of the best places to see cheetahs, as well as a few which require considerably more effort and luck. All rely on tourism for revenue.

Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana & South Africa. High chances to see cheetahs hunting, particularly during March-April when prey congregates in the Auob and Nossob river beds following the rains.

Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana & South Africa. High chances to see cheetahs hunting, particularly during March-April when prey congregates in the Auob and Nossob river beds following the rains.

Khar Touran National Park and Kavir National Park, Iran. The extremely rare Asiatic cheetah is an exceptional chance sighting throughout its range, but Khar Touran and Kavir have the best populations.

Khar Touran National Park and Kavir National Park, Iran. The extremely rare Asiatic cheetah is an exceptional chance sighting throughout its range, but Khar Touran and Kavir have the best populations.

Liuwa Plains National Park, Zambia. Home to one of the largest wildebeest migrations outside the Serengeti. Cheetahs are most often seen during the rainy season from November to January.

Liuwa Plains National Park, Zambia. Home to one of the largest wildebeest migrations outside the Serengeti. Cheetahs are most often seen during the rainy season from November to January.

Nxai Pan National Park, Botswana. The open pan habitat is excellent for cheetahs. Year-round congregations of springbok provide many chances to witness hunts.

Nxai Pan National Park, Botswana. The open pan habitat is excellent for cheetahs. Year-round congregations of springbok provide many chances to witness hunts.

Okavango Delta, Botswana. Cheetahs here have adapted to hunting in the watery habitat and the best areas are Chitabe Camp, and in the Moremi Game Reserve, Mombo Camp. In this unusual habitat cheetah densities are high due to the abundance of suitable prey.

Okavango Delta, Botswana. Cheetahs here have adapted to hunting in the watery habitat and the best areas are Chitabe Camp, and in the Moremi Game Reserve, Mombo Camp. In this unusual habitat cheetah densities are high due to the abundance of suitable prey.

Pendjari National Park, Benin. One of West Africa’s best cheetah-viewing sites. Sightings are localised in the Yangouali lagoon region.

Pendjari National Park, Benin. One of West Africa’s best cheetah-viewing sites. Sightings are localised in the Yangouali lagoon region.

Phinda Private Game Reserve, South Africa. A small population, but very habituated to vehicles. Around 95 per cent of visitors see at least one cheetah.

Phinda Private Game Reserve, South Africa. A small population, but very habituated to vehicles. Around 95 per cent of visitors see at least one cheetah.

Reserve Naturelle Nationale de L’Air et du Tenere, Niger. For the very intrepid. Cheetahs are extremely hard to see here but this is probably the best hope of spotting the very unusual Sahara desert form.

Reserve Naturelle Nationale de L’Air et du Tenere, Niger. For the very intrepid. Cheetahs are extremely hard to see here but this is probably the best hope of spotting the very unusual Sahara desert form.

Serengeti Plains-Masai Mara Ecosystem, Kenya & Tanzania. Africa’s largest protected population. Cheetahs are particularly visible on the short-grass plains. Aitong (Masai Mara) and Seronera (Serengeti) have high densities.

Serengeti Plains-Masai Mara Ecosystem, Kenya & Tanzania. Africa’s largest protected population. Cheetahs are particularly visible on the short-grass plains. Aitong (Masai Mara) and Seronera (Serengeti) have high densities.

The conservation challenges facing the cheetah are unique among large cats. Like all carnivores, cheetahs suffer from terrific human pressures, but they are also poor competitors in the carnivore hierarchy. Conservationists are discovering that for the cheetah to survive the next century, different cheetah populations require very different strategies.

CHEETAHS IN PROTECTED AREAS

The core of wildlife conservation in Africa is its system of protected areas. On paper at least, cheetahs occur in 140 major reserves and ‘wildlife management areas’ (which usually permit some level of utilisation such as trophy hunting). If their individual land areas are tallied, cheetahs are protected in almost a million square kilometres of Africa. The figures seem impressive, but generalisations like this conceal the conservation obstacles confronting cheetahs in reserves. For a start, many protected areas are ‘paper reserves’ only. The human pressure from livestock grazing or hunting is intense inside many parks, particularly in parts of west, central and north Africa, where wildlife is protected in name only. Where protection is effective, the cheetah faces another problem – other carnivores. As explained in Chapter Six (see pages 121–122), other large predators, especially lions, suppress the numbers of cheetahs. Lions, leopards and spotted hyaenas reach their highest densities in protected areas and there is a strong negative correlation between lion numbers and those of cheetahs. Where there are many lions, there are few cheetahs.

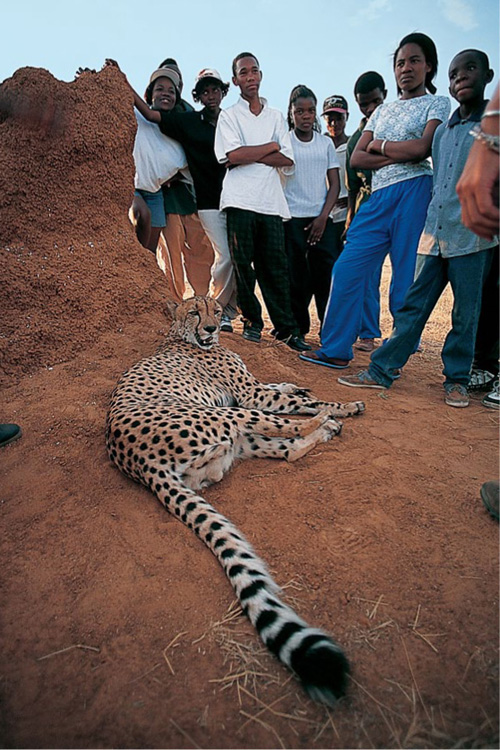

These tourists have paid top dollar to enjoy these young cheetahs playing at the Phinda Game Reserve, South Africa. Where a percentage of such income feeds back into surrounding communities, tourism can be a very successful means of protecting wildlife.

THE VALUE OF CHEETAHS IN CAPTIVITY

There are at least 1 300 cheetahs in captivity around the world, a figure that excludes most of those owned privately or illegally. Although success in captive breeding has reduced the number taken from the wild, about a quarter of cheetahs in zoos are wild-caught. From a population perspective, removing a cheetah from the wild is the same as killing it; it will never reproduce in that population so its genetic contribution is lost. Good zoos no longer accept wild-caught cheetahs but the question remains, what is the value of any cheetah in captivity? Most captive-born cheetahs fail to reproduce and are poor candidates for reintroduction to the wild; experimental releases of captive-born cheetahs have largely failed.

Even so, zoos make three significant contributions to cheetah conservation. The first is maintaining a genetic reservoir as insurance against extinction in the wild; hopefully, it will never be required but at least it is there. The second is in research; captive cheetahs provide opportunities to investigate questions that would be impossible to explore in the wild. The final and most compelling benefit of zoos is their ability to educate and inspire. Most people will never see a wild cheetah, but an encounter with a zoo cat might encourage a child to study biology or simply to convince its parents to donate to conservation. Better zoos, particularly in Australasia, Europe and North America, now have very active programmes of fund-raising that channel many millions of dollars towards conservation in the wild.

Protected areas also suffer from being conservation islands; they are isolated from other reserves by human-modified habitats where large predators cannot survive. Moreover, many reserves with cheetahs are too small to support anything other than a handful of breeding adults. Small populations are more likely to suffer the consequences of inbreeding and are more vulnerable to chance events such as disease outbreaks or natural disasters; all combine to increase the risk of extinction. Some small populations of cheetahs are already written off as ‘living dead,’ a term conservation biologists apply where there are simply too few animals for the population to survive beyond 50 years.

Is there any value for cheetahs in protected areas? For all their shortcomings, protected areas provide a crucial safeguard against extinction. Setting aside reserves and parks – and meeting the far greater challenge that they actually function as such – guarantees that a core population of cheetahs will be conserved. Their numbers will never be great, but the species will probably persist. So, for example, even though South Africa’s Kruger National Park protects only around 200 cheetahs, compared to perhaps 2 000 lions, the survival of those cheetahs is relatively certain – provided Kruger survives.

Needless to say, ensuring the persistence of parks carries its own enormous challenges. The human populations surrounding most African parks are large, ever increasing and hungry. If parks fail to generate revenue for the communities on their boundaries, they represent little more than somewhere to hunt or to graze livestock. In much of Africa, tourism is the principal means by which governments are able to fund a system of protected areas. The fees paid by tourists translate into employment. Where local people make their living as rangers, guides and lodge staff, or by selling goods and services to the tourist traffic passing through, the need to hunt wildlife and convert habitat into pastures or fields is reduced.

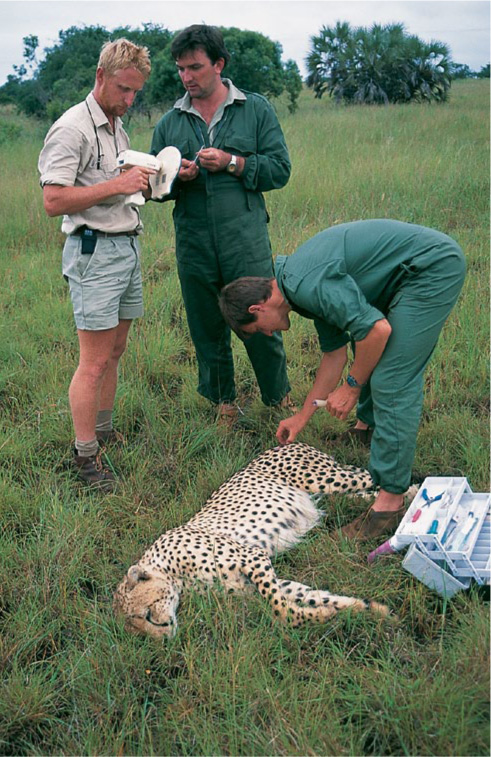

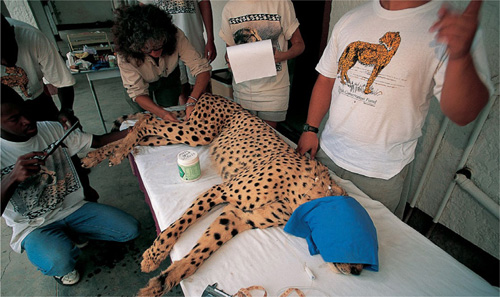

Translocating cheetahs: a sedated cheetah in a transport crate. Easily caught and surprisingly tolerant of the trauma of being translocated, wild cheetahs make robust candidates for reintroduction programmes. Careful monitoring of translocated cheetahs by radio-collars and other methods is critical when assessing the success of such programmes. Many hundreds of cheetahs have been set free without such post-release research and have simply disappeared.

CAN HUNTING CONSERVE?

Although the idea of shooting a cheetah for recreation is abhorrent to many, trophy hunting can contribute to conserving the cheetah – at least in theory. Where cheetahs inhabit privately owned farms, permitting landowners to sell one or two individuals a year to trophy hunters might encourage them to tolerate all cheetahs on their land. By generating income, the cheetah becomes an asset rather than a valueless liability that farmers shoot anyway in defence of their stock. The system relies on effective regulation so that farmers are limited to a sustainable quota of cheetah trophies but even so, the evidence that hunting helps conserve the species is slim. Only a handful of farmers benefit from the occasional trophy hunt – and most of those who do still shoot cheetahs anyway. One possible solution is to permit more hunting; however, to convince farmers that the profits outweigh their (real or imagined) stock losses to cheetahs would entail a hefty increase in the number of trophies. Provided that figure is less than the number currently destroyed by farmers, the species may benefit in the end, but the reality is that wherever there is farming, persecution of cheetahs will continue.

Tourism has been criticised for its impact on cheetahs, and it is true that cheetahs are generally more prone to disturbance than other large African carnivores. Among their documented effects, tourist vehicles harass shy cheetahs, interrupt hunts by frightening off prey, and occasionally even drive over young cubs. Even so, the only study that rigorously investigated the problem, in Kenya’s Masai Mara Game Reserve, found that the effect on most cheetahs was negligible. Some even benefited from vehicles which provided cover for hunts, distracted prey or woke up snoozing cheetahs, prompting them to notice prey nearby. Clearly, any tourism needs regulation and education to ensure appropriate behaviour from cheetah-watchers but, on balance, it is a far greater benefit than a detriment. Well established in southern and East Africa, wildlife tourism is slowly making inroads into less accessible areas, where it has the potential to make the difference between survival and extinction for large carnivores (see box ‘Top cheetah spots’ on page 129).

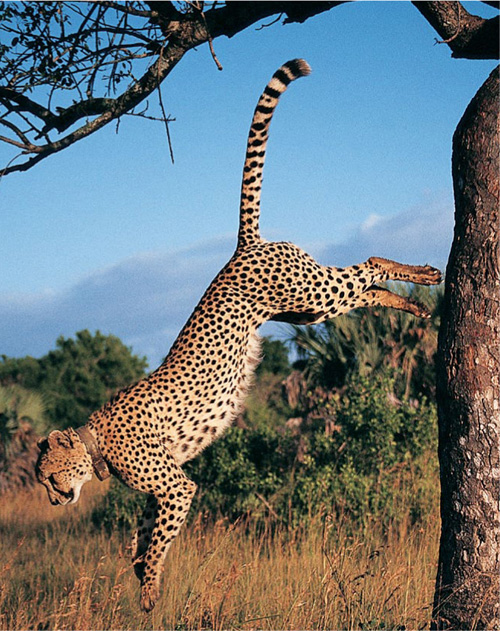

A radio-collared male cheetah leaps from a marula tree, South Africa. Radio-collars provide detailed biological information that would be impossible to collect otherwise. Contrary to widely repeated opinion, they do not bother the study animal or alter its behaviour when correctly fitted.

Conservationists are also addressing the isolation of parks, albeit gradually. Meta-population (literally, ‘a population of populations’) management attempts to treat physically isolated populations of cheetahs as they interacted before human activity carved wilderness into fragments. Mimicking natural processes such as immigration and dispersal, biologists translocate individuals between different reserves to enhance the genetic diversity in isolated populations. Even better, reintroductions of cats into areas they once occupied restore the natural connections between populations.

Meta-population projects have exciting potential, but there are substantial obstacles to success. Translocated cheetahs ‘home’, attempting to head back to the area they know, even if it is hundreds of kilometres away. To some extent, housing translocated cheetahs at the release site in large enclosures for a few weeks of acclimatisation overcomes the problem. Known as a ‘soft release’, the method seems to ease the ordeal of capture and translocation, and encourages cheetahs to settle in the new area. There have been significant soft-release successes in South Africa but, importantly, all ‘reclaimed’ conservation areas are fortified with electrified fences. Under pressure, cheetahs could easily cross the fence, but it acts as a further deterrent to their wandering behaviour. Notably, a trio of males soft-released in Zambia’s unfenced Lower Zambezi National Park headed straight out of the park towards the direction of home. Two died in snares within six weeks of release and the third disappeared.

Setbacks notwithstanding, the projects have revealed that cheetahs can thrive when reintroduced. In KwaZulu-Natal’s Phinda Game Reserve, at least 86 cubs were born to reintroduced adults between 1993 and 2002; as adults, many of the Phinda-born cheetahs have seeded other restoration projects around South Africa. Most importantly, the lessons learned could be applied to countries where the cheetah is extinct. There are currently proposals to reintroduce the cheetah into India, Saudi Arabia and Uzbekistan. The socio-economic obstacles confronting the schemes are enormous and they may never come to fruition, but if governments can address the human factor, the indications from Africa suggest that cheetahs will take care of the rest.

Not surprisingly, meta-population strategies require considerable resources and expertise. Additionally, while encouraging, they benefit relatively few cheetahs; only a small number of cheetahs can ever inhabit protected areas and there are very real limits to the amount of land available for reclamation. Further, nations struggling to defend their established protected areas against the weight of human pressure have little hope of restoring even more land for wildlife. All of which combines to shift the conservation focus away from parks and reserves. For the cheetah’s long-term survival to be a sure thing, the solution rests beyond park boundaries.

With around 17% of its land area under some sort of protection, Botswana is one of the few remaining African countries where cheetahs can roam over massive areas with a low danger of human persecution. Even so, the species has never been properly studied there; the number of wild cheetahs in Botswana and the species’ conservation status is entirely unknown.

CHEETAHS OUTSIDE PROTECTED AREAS

Throughout much of its range, the cheetah is found in greater numbers outside national parks and reserves than within them. Outside the boundaries of protected areas, large predators invariably confront their greatest threat: people. Ironically, that can work in the cheetah’s favour because lions and, less so, spotted hyaenas and leopards, are simply not tolerated. Lions kill livestock and occasionally people, so when one leaves the protection of a reserve, it is on borrowed time. There are now very few lion populations outside protected areas; in fact, without reserves, lions would be driven to extinction.

Lion-free regions have the potential to act as cheetah refuges, but of course only if cheetahs themselves are not persecuted. Around the parks of Kenya and Tanzania, the pastoral Masai represent a sort of coexistence model, albeit an imperfect one. The Masai have little interest in hunting herbivores so cheetah prey is usually abundant on Masai lands. Furthermore, understanding that cheetahs are far less dangerous to their herds than lions, leopards or hyaenas, the Masai rarely go out of their way to kill a cheetah. Nor do cheetahs take the poisoned baits left for stock-killers. Although it is not an entirely amicable relationship – cheetahs are killed from time to time by young herd-boys testing their skills, or perhaps because the skin can be sold – the Masai demonstrate that fairly high densities of cheetahs can live alongside people and their livestock.

Elsewhere in Africa, the association is rarely as conflict-free. The explanation lies partially in the Masai’s indifference to firearms. Traditionally, predators are hunted with short stabbing spears, a method that still prevails over the use of rifles and, although not exactly predator friendly, limits the impact on carnivore numbers. Where farmers use guns – and this encompasses the great percentage of pastoral Africa – persecution is indiscriminate and far more destructive. Given the chance, most farmers shoot cheetahs. It is legal in most countries if the cheetah is deemed a threat to livestock and even where it is not, enforcement is largely non-existent and farmers shoot cheetahs anyway. Legality and weapons-of-choice aside, it begs the question, if the Masai are able to live with cheetahs, why not all farmers?

The problem of conflict remains. Cheetahs are not nearly as destructive as lions and other large predators, but they do kill livestock. The Masai suffer little because they live with their animals; lions kill stray cattle, and leopards sometimes raid corrals at night, but depredation (losses to predators) by cheetahs is almost non-existent. Cheetahs do not enter villages to hunt and will not confront a Masai defending his herd. The pattern breaks down on the vast commercial ranches of East and southern Africa where cheetahs and unattended stock roam free. In this scenario, sheep, goats or young calves are vulnerable to cheetahs and although losses to cheetahs are generally low, even the most tolerant farmers can endure only so much depredation before the financial imperative compels them to start shooting.

The issue for conservation on ranches becomes one of alleviating conflict, and the solutions are an ingenious combination of education and utilisation. In Namibia, conservation organizations such as the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) and AfriCat are leading the way. They have demonstrated that simple changes in livestock husbandry practices can reap dramatic benefits. Electrified fencing deters cheetahs from livestock areas, and corralling stock overnight or when calves are young, as the Masai do, reduces losses.

CCF has also pioneered the use of the Anatolian shepherd dog, or Akbash, in Namibia. Originating in Turkey where they have guarded herds against wolves and bears for 6 000 years, the dogs are bonded to the herd as puppies and grow up with their charges. When confronted with a predator, the Akbash rushes to confront it rather than herd its charges, the method adopted by traditional African dog breeds, which creates panic and movement in the herd – irresistible to a hungry cheetah. In country-wide education programmes, CCF shows farmers how the combination of a guard dog with a herder – essentially the Masai model – can almost eliminate losses to cheetahs.

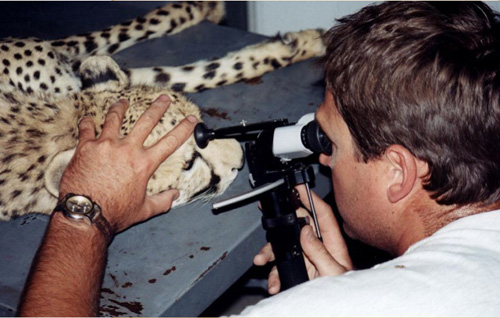

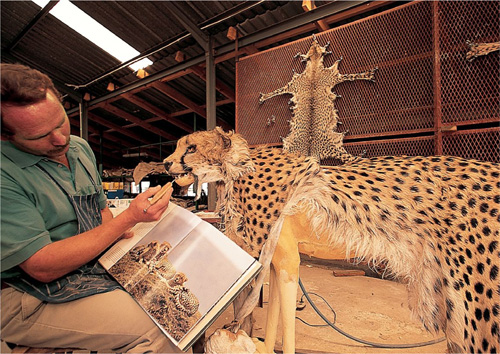

Zoologists in Namibia and South Africa ‘processing’ captured individuals. The collection of biological measurements and samples from wild cheetahs makes a critical contribution towards understanding their biology.

A relaxed family group of cheetahs. Views of cheetahs such as this are only possible where they are not persecuted. Outside protected areas, cheetahs are typically very shy and difficult to observe. Without dedicated conservation action, the opportunity to enjoy magnificent encounters with cheetahs such as this may be lost.

The Namibian groups have made very impressive progress, but their methods do not work everywhere. Research conducted by CCF and AfriCat reveals that cheetahs usually eschew taking domestic stock where there is a natural alternative. On the huge Namibian ranches where wild herbivores are often abundant, the conflict problem would seem to be solved. However, in Namibia the landowner owns the wildlife ranging freely on the property. The same applies to numerous African countries where, if not having outright ownership of wildlife, the landowner is permitted by the government to utilise it. Namibian farmers harvest wild ungulates – springbok, kudu, gemsbok and others – for their skins and meat, or to sell to trophy hunters and other farmers wishing to buy the live animals. To game farmers, antelopes are just as valuable (or more so) than cattle. When cheetahs compete with farmers for wild herbivores, the obstacles to conservation are far greater. Guard dogs, corrals and herders simply do not work.

One possible solution is the argument characterised as ‘if it pays, it stays’; if cheetahs are valuable to farmers, they will be treated accordingly. In the most controversial application of the idea, three countries – Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe – permit trophy hunting of cheetahs. Whether or not hunting succeeds in conserving the cheetah is debatable (see box ‘Can hunting conserve?’ on page 132); regardless, very few cheetahs are shot by hunters each year. Namibia’s quota is the highest at 150 (which includes live exports), but the difficulty of finding a cheetah during the allocated hunting period means that the quota is never filled; in 2000, 87 cheetahs were hunted, far fewer than those farmers destroyed themselves. A similar proposal from South Africa would permit limited hunting of cheetahs in the country’s far north-west, where a small population lives on farmlands.

The alternative to hunting brings us full circle to the cheetah as tourist attraction for safari-goers. In a few pockets of Africa, the increasing demand from tourists hungry for photogenic wildlife is giving commercial farmers reason for pause. In marginal areas, where the yearly profit from stock farming is poised on a knife’s edge, wildlife can represent a more productive and reliable source of income. A handful of farmers are now encouraging the return of wildlife to attract the tourism dollar. In South Africa, where the trend is most vigorous, growing wildlife tourism is the principal drive behind the reintroduction projects of cheetahs discussed earlier in this chapter (see pages 128–136). In Namibia, where reintroduction is unnecessary, a few farmers are simply growing to tolerate cheetahs because the tourists who visit their properties want to see them. Although presently limited to a few areas of southern and East Africa, private conservancies are holding increasing promise for cheetahs.

Known to biologists as lacrimal lines, the cheetah’s unique tear streaks have no known function. One theory holds that they help to line up prey like a rifle’s cross hairs but, more believably, they probably reduce reflected glare during day-time hunting. There are still many mysteries surrounding the cheetah, despite its being a conspicuous and well-studied species. The dedication of scientists and conservationists in unraveling the biology of this enigmatic cat is a cornerstone in ensuring the cheetah’s persistence.

For all its vulnerability, the cheetah has demonstrated astonishing resilience. It has shown the ability to live in a far wider range of habitats than is usually assumed, it has a prodigious ability to reproduce, and where conditions are favourable it has the capacity to recolonise areas swiftly. Exemplified by its uneasy, but enduring, relationship with the Masai and farmers in Namibia, it has also displayed a rare ability to live alongside humans. Together, these characteristics give the cheetah a decent chance at evading extinction, but only if people make the active decision to allow it. The threats confronting the cheetah today are greater than ever, and they arise above all from our activities. Whether the cheetah lives or dies is entirely in our hands.