XXIX. THE COURSE OF THE TRAGEDY

(1) A SOCIAL BARRAGE

WHEN

a growing civilization breaks down through the deterioration of an attractively creative into an odiously dominant minority, one of the results is the estrangement of its former proselytes in the once primitive societies round about, which the civilization in its growth stage was influencing in divers degrees by the effect of its cultural radiation. The ex-proselytes’ attitude changes from an admiration expressing itself in mimesis to a hostility breaking out into warfare, and this warfare may have one or other of two alternative outcomes. On a front on which the local terrain

offers the aggressive civilization the possibility of advancing up to a natural frontier in the shape of some unnavigated sea or untraversed desert or unsurmounted mountain range, the barbarians may be decisively subjugated; but, where such a natural frontier is absent, geography is apt to militate in the barbarians’ favour. Where the retreating barbarian has open to him, in his rear, an unlimited field of manoeuvre, the shifting battle-front is bound, sooner or later, to arrive at a line at which the aggressive civilization’s military superiority will be neutralized by the handicap of the ever-lengthening distance of the front from the aggressor’s base of operations.

Along this line a war of movement will change into a static war without having reached any military decision, and both parties will find themselves in stationary positions in which they will be living side by side, as the creative minority of the civilization and its prospective proselytes were living before the breakdown of the civilization set them at variance with one another. But the psychological relation between the parties will not have reverted from hostility to its previous creative interplay, and there will have been no restoration, either, of the geographical conditions under which this cultural intercourse once took place. In the growth stage, the civilization gradually shaded off into a surrounding barbarism across a broad threshold which offered the outsider an easy access to an inviting vista within. The change from friendship to hostility has transformed this conductive cultural threshold (limen

) into an insulating military front (limes

). This change is the geographical expression of the conditions that generate an heroic age.

An heroic age is, in fact, the social and psychological consequence of the crystallization of a limes;

and our purpose now is to trace this sequence of events. A necessary background to this undertaking is, of course, a survey of the barbarian war-bands that had breasted divers sections of the limites

of divers universal states, and a survey of this kind has already been attempted in an earlier part of this Study, in the course of which we have noted the distinctive achievements of these war-bands in the fields of sectarian religion and epic poetry. In our present inquiry this foregoing survey can be drawn upon for purposes of illustration without having to be recapitulated.

A military limes

may be likened to a forbidding barrage across a no longer open valley—an imposing monument of human skill and power setting Nature at defiance, and yet precarious, because a defiance of Nature is a tour de force

on which Man cannot venture with impunity.

‘The Arab-Muslim tradition relates that once upon a time there was to be seen in the Yaman a colossal work of hydraulic engineering known as the dam or dyke of Ma’rib, where the waters descending from the eastern mountains of the Yaman collected in an immense reservoir and thence irrigated an immense tract of country, giving life to an intensive system of cultivation and thereby supporting a dense population. After a time, the tradition goes on to relate, this dam broke, and, in breaking, devastated everything and cast the inhabitants of the country into a state of usch dire distress that many tribes were compelled to emigrate.’

1

This story has served to account for the initial impulse behind an Arab Vôlkerwanderung that eventually swept out of the Arabian Peninsula with an impetus which carried it across the Tien Shan and the Pyrenees. Translated into a simile it becomes the story of every limes

of every universal state. Is this social catastrophe of the bursting of the military dam an inevitable tragedy or an avoidable one? To answer this question we must analyse the social and psychological effects of the barrage-builders’ interference with the natural course of relations between a civilization and its external proletariat.

The first effect of erecting a barrage is, of course, to create a reservoir above it; but the reservoir, however large, will have its limits. It will never cover more than a fraction of even its own catchment basin. There will be a sharp distinction between the submerged tract immediately above the barrage and a region at the back of beyond which is left high and dry. In a previous context we have already observed the contrast between the effect of a limes

on the life of barbarians within its range and the undisturbed torpidity of primitive peoples in a more distant hinterland. The Slavs continued placidly to lead their primitive life in the Pripet Marshes throughout the span of two millennia which first saw the Achaean barbarians convulsed by their proximity to the European land-frontier of ‘The thalassocracy of Minos’ and then saw the Teuton barbarians going through the same experience as a result of their proximity to the European land-frontier of the Roman Empire. Why are the barbarians in the ‘reservoir’ so exceptionally upset? and what is the source of a subsequent access of energy which has enabled them invariably to break through the limes

? We may find answers to these questions if we follow out our simile in terms of its geographical setting in Eastern Asia.

Let us suppose the imaginary dam that symbolizes a limes

in our simile to have been built astride some high valley in the region actually traversed by the Great Wall within the latter-day Chinese provinces of Shinsi and Shansi. What is the ultimate source of that formidable body of water pressing in ever-increasing volume upon the dam’s up-stream face? Though the water must manifestly all have come down-stream from above the dam, its ultimate source cannot lie in that direction, for the distance between the dam and the watershed is not great, and behind the watershed stretches the dry Mongolian Plateau. The ultimate source of supply is, in fact, to be found, not above the dam but below it, not on the Mongolian Plateau but in the Pacific Ocean, whose waters have been transformed by the sun into vapour and carried by an east wind until, condensed by cold air, they fall as rain into the catchment basin. The psychic energy that accumulates on the barbarian side of the limes

is derived only in an inconsiderable measure from the transfrontier barbarians’ own exiguous social heritage; the bulk of it is drawn from the vast stores of the civilization which the barrage has been built to protect.

How is this transformation of psychic energy brought about? The transformation process is the decomposition of a culture and its recomposition in a new pattern. Elsewhere in this Study we have compared the social radiation of culture to the physical radiation of light, and here we must recall the ‘laws’ at which we arrived in that context.

The first law is that an integral culture ray, like an integral light ray, is diffracted into a spectrum of its component elements in the course of penetrating a recalcitrant object.

The second law is that the diffraction may also occur, without any impact on an alien body social, if the radiating society has already broken down and gone into disintegration. A growing

civilization can be defined as one in which the components of its culture—the economic, the political, and the ‘cultural’ in the stricter sense—are in harmony with one another; and, on the same principle, a disintegrating civilization can be defined as one in which these three elements have fallen into discord.

Our third law is that the velocity and penetrative power of an integral culture, ray are averages of the diverse velocities and penetrative powers which its economic, political, and ‘cultural’ components display when, as a result of diffraction, they travel independently of each other. The economic and political components travel faster than the undiffracted culture; the ‘cultural’ component travels more slowly.

Thus, in the social intercourse between a disintegrating civilization and its alienated external proletariat across a military limes

, the diffracted radiation of the civilization suffers a woeful impoverishment. Practically all intercourse is eliminated except what is economic and political—trade and war; and of these the trade, for various reasons, comes to be more and more restricted and the warfare to be more and more inveterate. Under these sinister auspices, such selective mimesis as occurs takes place on the barbarians’ own initiative. They show their initiative in imitating those elements which they accept in a manner which will disguise the distasteful source of what has been imitated. Examples both of recognizable adaptations and of virtually new creations have been given already in an earlier part of this Study. Here we need only recall that the ‘reservoir’ barbarians are apt to borrow the higher religion of an adjoining civilization in the form of a heresy (for example, the Arian heretical Christianity of the Goths), and the Caesarism of an adjoining universal state in the form of an irresponsible kingship, resting not on tribal law but on military prestige, while the barbarian capacity for original creation is displayed in heroic poetry.

(2) THE ACCUMULATION OF PRESSURE

The social barrage created by the establishment of a limes

is subject to the same law of Nature as the physical barrage created by the construction of a dam. The water piled up above the dam seeks to regain a common level with the water below it. In the structure of a physical dam the engineer introduces safety-valves in the form of sluices, which can be opened or closed as circumstances require, and this safeguarding device is not overlooked by the political engineers of a military limes

, as we shall see. In this case, however, the device merely precipitates the cataclysm. In the

maintenance of a social dam the relief of pressure by a regulated release of water is impracticable; there can be no discharge from the reservoir without the undermining of the dam; for the water above the dam, instead of rising and falling with the alternations of wet and dry weather, is, in the nature of the case, continuously on the rise. In the race between attack and defence, the attack cannot fail to win in the long run. Time is on the side of the barbarians. The time, however, may be long drawn out before the barbarians behind the limes

achieve their break-through into the coveted domain of the disintegrating civilization. This long period, during which the spirit of the barbarians has been profoundly affected, and distorted, by the influence of the civilization from which they have been barred out, is the necessary prelude to an ‘heroic age’, in which the limes

collapses and the barbarians have their fling.

The erection of a limes

sets in motion a play of social forces which is bound to end disastrously for the builders. A policy of non-intercourse with the barbarians beyond is quite impracticable. Whatever the imperial government may decide, the interests of traders, pioneers, adventurers, and so forth will inevitably draw them beyond the frontier. A striking illustration of this tendency among the marchmen of a universal state to make common cause with the barbarians beyond the pale is afforded by the history of the relations between the Roman Empire and the Hun Eurasian Nomads who broke out of the Eurasian Steppe towards the end of the fourth century of the Christian Era. Though the Huns were unusually ferocious barbarians, and though their ascendancy along the European limes

of the Roman Empire was ephemeral, a record of three notable cases of fraternization has survived among the fragmentary remnants of contemporary accounts of this brief episode. The most surprising of these cases is that of a Pannonian Roman citizen named Orestes, whose son Romulus Augustulus was to achieve an ignominious celebrity as the last Roman Emperor in the West; this same Orestes was for a time employed by the celebrated Hun warlord Attila as his secretary.

Of all the goods which passed outwards across the ineffectively insulating limes

, weapons of war were perhaps the most significant. The barbarians could never have attacked effectively without the use of the weapons forged in the arsenals of civilization. On the North-West Frontier of the British Indian Empire from about 1890 onwards, ‘the influx of rifles and ammunition into tribal territory … completely changed the nature of border warfare’;

1

and, while the transfrontier Pathans’ and Baluchīs’ earliest source

of supply of up-to-date Western small-arms was systematic robbery from the British Indian troops on the other side of the line, ‘there would … have been little cause for apprehension, had it not been for the enormous growth of the arms traffic in the Persian Gulf, which, both at Bushire and [at] Muscat, was at first in the hands of British traders’

1

—a striking example of the tendency for private interests of the empire’s subjects in doing business with the transfrontier barbarians to militate against the public interest of the imperial government in keeping the barbarians at bay.

The transfrontier barbarian is not, however, content simply to practise the superior tactics which he has learnt from an adjoining civilization; he often improves upon them. For example, on the maritime frontiers of the Carolingian Empire and of the Kingdom of Wessex, the Scandinavian pirates turned to such good account a technique of ship-building and seamanship which they had acquired, perhaps, from the Frisian maritime marchmen of a nascent Western Christendom that they captured the command of the sea and, with it, the initiative in the offensive warfare which they proceeded to wage along the coasts and up the rivers of the Western Christian countries that were their victims. When, pushing up the rivers, they reached the limits of navigation, they exchanged one borrowed weapon for another and continued their campaign on the backs of stolen horses, for they had mastered the Frankish art of cavalry fighting as well as the Frisian art of navigation.

In the long history of the war-horse, the most dramatic case in which this weapon had been turned by a barbarian against the civilization from which he had acquired it was to be found in the New World, where the horse had been unknown until it had been imported by post-Columbian Western Christian intruders. Owing to the lack of a domesticated animal which, in the Old World, had been the making of the Nomad stockbreeder’s way of life, the Great Plains of the Mississippi Basin, which would have been a herdsman’s paradise, had remained the hunting-ground of tribes who followed their game laboriously on foot. The belated arrival of the horse in this ideal horse-country had effects on the life of the immigrant and the life of the native which, while in both cases revolutionary, were different in every other respect. The introduction of the horse on to the plains of Texas, Venezuela, and Argentina made Nomad stockbreeders out of the descendants of 150 generations of husbandmen, while at the same time it made mobile mounted war-bands out of the Indian tribes of the Great Plains beyond the frontiers of the Spanish viceroyalty of New Spain and

of the English colonies that eventually became the United States. The borrowed weapon did not give these transfrontier barbarians the ultimate victory, but it enabled them to postpone their final discomfiture.

While the nineteenth century of the Christian Era saw the prairie Indian of North America turn one of the European intruder’s weapons against its original owner by disputing with him the possession of the Plains with the aid of the imported horse, the eighteenth century had already seen the forest Indian turn the European musket to account in a warfare of sniping and ambuscades which, with the screening forest as the Indian’s confederate, had proved more than a match for contemporary European battletactics, in which close formations, precise evolutions, and steady volleys courted destruction when unimaginatively employed against adversaries who had adapted the European musket to the conditions of the American forest. In days before the invention of firearms, corresponding adaptations of the current weapons of an aggressive civilization to forest conditions had enabled the barbarian denizens of the Transrhenane forests of Northern Europe to save a still forest-clad Germany from the Roman conquest that had overtaken an already partially cleared and cultivated Gaul, by inflicting on the Romans a decisively deterrent disaster in the Teutoburger Wald in A.D.

9.

The line along which the military frontier between the Roman Empire and the North European barbarians consequently came to rest for the next four centuries carries its own explanation on the face of it. It was the line beyond which a forest that had reigned since the latest bout of glaciation was still decisively preponderant over the works of Homo Agricola

—works which had opened the way for the march of Roman legions from the Mediterranean up to the Rhine and the Danube. Along this line, which happened, unfortunately for the Roman Empire, to be just about the longest that could have been drawn across Continental Europe, the Roman Imperial Army had henceforward to be progressively increased in numerical strength to offset the progressive increase in the military efficiency of the transfrontier barbarians whom it was its duty to hold at bay.

On the local anti-barbarian frontiers of the still surviving parochial states of a Westernizing world which, at the time of writing, embraced all but a fraction of the total habitable and traversable surface of the planet, two of the recalcitrant barbarians’ nonhuman allies had already been outmanœuvred by a Modern Western industrial technique. The Forest had long since fallen a victim to cold steel, while the Steppe had been penetrated by the

motor-car and the aeroplane. The barbarian’s mountain ally, however, had proved a harder nut to crack, and the highlander rear-guard of Barbarism had been displaying, in its latest forlorn hopes, an impressive ingenuity in turning to its own advantage, on its own terrain

, some of the latter-day devices of an industrial Western military technique. By this tour de force

the Rīfī high-landers astride the theoretical boundary between the Spanish and French zones of Morocco had inflicted on the Spaniards at Anwal in A.D.

1921 a disaster comparable with the annihilation of Varus’s three legions by the Cherusci and their neighbours in the Teuto-burgerwald in A.D.

9, and had made the French Government in North-West Africa rock on its foundations in A.D.

1925. By the same sleight of hand the Mahsūds of Waziristan had baffled repeated British attempts to subdue them during the ninety-eight years between A.D.

1849, when the British had taken over this anti-barbarian frontier from the Sikhs, and A.D.

1947, when they disencumbered themselves of a still unsolved Indian North-West Frontier problem by bequeathing this formidable legacy to Pakistan.

In A.D.

1925 the Rīfī offensive came within an ace of cutting the corridor which linked the effectively occupied part of the French Zone of Morocco with the main body of French North-West Africa; and, if the Rīfīs had succeeded in an attempt which failed by so narrow a margin, they would have put in jeopardy the whole of the French Empire on the southern coast of the Mediterranean. Interests of comparable magnitude were at stake for the British Rāj in India in the trial of strength between the Mahsūd barbarians and the armed forces of the British Indian Empire in the Waziristan campaign of A.D.

1919–20. In this campaign, as in the Rīfī warfare, the barbarian belligerent’s strength lay in his skilful adaptation of Modern Western arms and tactics to a terrain

that was unpropitious for their use on the lines that were orthodox for their Western inventors. The elaborate and costly equipment which had been invented on the European battlefields of the war of A.D.

1914–18, in operations on level ground between organized armies, was much less effective against parties of tribesmen lurking in a tangle of mountains.

1

In order to defeat, even inconclusively, transfrontier barbarians who have attained the degree of military expertise

shown by the Mahsūds in A.D.

1919 and by the Rīfīs in A.D.

1925, the Power behind

the threatened limes

has to exert an effort that—measured in terms either of manpower or of equipment or of money—is quite disproportionate to the slender resources of its gadfly opponents to which this ponderous counter-attack is the irreducible minimum of effective response. Indeed, what Mr. Gladstone in A.D.

1881 called ‘the resources of civilization’

1

could be almost as much of a hindrance as a help in warfare of this kind, for the mobility of British Indian forces was impaired by the multitude of the gadgets on which it depended for the assertion of its superiority. Again, if the British Indian forces were hindered by their too-muchness from striking rapidly and effectively, the Mahsūds presented too little to strike at. The purpose of a punitive expedition is to punish, but how was one to punish such people as these? Reduce them to destitution? They were destitute already; they took this state of life for granted, even if they did not enjoy it. Their lives were already—in the terms of Thomas Hobbes’s description of the ‘State of Nature’—solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. It was hardly possible to make them more solitary, poorer, nastier, more brutish, and shorter; and, if it were possible, could one be sure that they would greatly care? We are here reaching a point that has been made in a different context in an earlier part of this Study—that a primitive body social recovers more easily and rapidly than a body social enjoying high material civilization. It is like the humble worm which, when cut in half, takes no notice and carries on as before. But we must return from the Rīfīs and Mahsūds, who have failed—so far—to carry through to a successful conclusion their assaults upon civilizations, and resume our examination of the process of the tragedy in cases where it has gone through to its Fifth Act.

The crescendo

of frontier warfare, which produced this progressive change in the balance of military power, progressively weakens the civilization involved by putting its monetary economy under the strain of an ever-increasing burden of taxation. On the other hand, it merely stimulates the military appetite of the barbarians. If the transfrontier barbarian had remained an unmodified primitive man, a much greater proportion of his total energies would have been devoted to the arts of peace and a correspondingly greater coercive effect would have been produced upon him by the punitive destruction of the products of his pacific labours. The tragedy of a hitherto primitive society’s moral alienation from the neighbouring

civilization is that the barbarian has neglected his former peaceful productivity in order to specialize in the art of border warfare, first in self-defence but afterwards as an alternative and more exciting method of earning his living—to plough and reap with sword and spear.

This striking inequality in the material consequences of border warfare for the two belligerents is reflected in the great and growing inequality between them in moral

. For the children of a disintegrating civilization, the interminable border warfare spells the burden of an ever-increasing financial charge. For the barbarian belligerents, on the other hand, the same warfare is not a burden but an opportunity, not an anxiety but an exhilaration. In this situation it is not surprising that the party which is both author and victim of the limes

should not resign himself to his doom without trying the last expedient of enlisting his barbarian adversary on his own side. We have already examined the consequences of this policy in an earlier part of this Study, and here we need only recall our previous finding, that this expedient for averting the collapse of a limes

actually precipitates the catastrophe which it was designed to forestall.

In the history of the Roman Empire’s struggle to arrest an inexorable inclination of the scales in favour of the transfrontier barbarians, the policy of enlisting barbarians to keep their fellow barbarians at bay defeated itself—if we are to believe a hostile critic of the Emperor Theodosius I’s administration—by initiating the barbarians into the Roman art of war and at the same time apprising them of the Empire’s weakness.

‘In the Roman forces, discipline was now at an end, and all distinction between Roman and barbarian had broken down. The troops of both categories were all completely intermingled with one another in the ranks; for even the register of the soldiers borne on the strength of the military units was now no longer being kept up to date. The [barbarian] deserters [from the transfrontier barbarian war-bands to the Roman Imperial Army] thus found themselves free, after having been enrolled in Roman formations, to go home again and send off substitutes to take their place until, at their own good time, they might choose to resume their personal service under the Romans. This extreme disorganization that was thus now prevalent in the Roman military formations was no secret to the barbarians, since—with the door thrown wide open, as it had been, for intercourse—the deserters were able to give them full intelligence. The barbarians’ conclusion was that the Roman body politic was being so grossly mismanaged as positively to invite attack.’

1

When such well-instructed mercenaries change sides en masse

,

it is no wonder that they are often able to give the coup de grâce

to a tottering empire; but we have still to explain why they should be moved, as they so frequently have been, to turn against their employers. Does not their personal interest coincide with their professional obligation? The regular pay they are now drawing is both more lucrative and more secure than the plunder that they used to snatch on occasional raids. Why, then, turn traitor? The answer is that, in turning against the empire that he has been hired to defend, the barbarian mercenary is indeed acting against his own material interests, but that in doing so he is not doing anything peculiar. Man seldom behaves primarily as homo economicus

, and the traitor mercenary’s behaviour is determined by an impulse stronger than any economic considerations. The plain fact is that he hates the empire whose pay he has taken; and the moral breach between the two parties cannot be permanently mended by a business deal which is not underwritten by any real desire, on the barbarian’s side, to share in the civilization that he has undertaken to guard. His attitude towards it is no longer one of reverence and mimesis, as was that of his ancestors in happier days when the same civilization was still in its attractive growth stage. The direction of the current of mimesis has, indeed, long since been reversed, and, so far from the civilization’s retaining prestige in the barbarian’s eyes, it is the barbarian who now enjoys prestige in the eyes of the representative of civilization.

‘Early Roman history has been described as the history of ordinary people doing extraordinary things. In the Later Empire it took an extraordinary man to do anything at all except carry on a routine; and, as the Empire had devoted itself for centuries to the breeding and training of ordinary men, the extraordinary men of its last ages—Stilicho, Aëtius, and their like—were increasingly drawn from the Barbarian world.’

1

(3) THE CATACLYSM AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

When the barrage bursts, the whole body of water that has been accumulating above the dam runs violently down a steep place into the sea, and this release of long-pent-up forces produces a threefold catastrophe. In the first place, the flood destroys the works of Man in the cultivated lands below the broken barrage. In the second place, the potentially life-giving water pours down to the sea and is lost without ever having served Man for his human purposes. In the third place, the discharge of waters empties the

reservoir, leaving its shores high and dry and thus dooming to death the vegetation which had been able to strike root there. In short, the waters which were fructifying so long as the barrage held, make havoc everywhere, in the lands that they lay bare as well as in the lands that they submerge, so soon as the bursting of the barrage releases them from the control which the presence of the barrage had imposed upon them.

This episode in Man’s contest with Physical Nature is an apt simile of what happens on the collapse of a military limes

. The resulting social cataclysm is a calamity for all concerned; but the incidence of the devastation is unequal and the reverse of what might have been expected, for the principal sufferers are not the ex-subjects of the defunct universal state but the ostensibly triumphant barbarians themselves. The hour of their triumph proves to be the occasion of their discomfiture.

What is the explanation of this paradox? It is that the limes

had served not only as a bulwark of civilization but also as a providential safeguard for the aggressive barbarian himself against demoniacally self-destructive forces within his own bosom. We have seen that the proximity of a limes

induces a malaise among the transfrontier barbarians within range of it because their previously primitive economy and institutions are disintegrated by a rain of psychic energy, generated by the civilization within the limes

, that is wafted across a barrier which is itself an obstacle to the fuller and more fruitful intercourse characteristic of the relations between a growing civilization and the primitive proselytes beyond its open and inviting limen

. We have also seen that, so long as the barbarian is confined beyond the pale, he succeeds in transmuting some, at least, of this influx of alien psychic energy into cultural products—political, artistic, and religious—which are partly adaptations of civilized institutions and partly new creations of the barbarian’s own. In fact, so long as the barrage holds the psychological disturbance to which the barbarian is being exposed is being kept within bounds within which it can produce a not wholly demoralizing effect; and this saving curb is provided by the existence of the very limes

which the barbarian is bent on destroying; for the limes

, so long as it holds, supplies a substitute, in some measure, for the discipline of which Primitive Man is deprived when the breaking of his cake of primitive custom converts him into a transfrontier barbarian. The limes

disciplines him by giving him tasks to perform, objectives to reach, and difficulties to contend with that constantly keep his efforts up to the mark.

When the sudden collapse of the limes

sweeps this safeguard away, the discipline is removed and at the same time the barbarian

is called upon to perform tasks which are altogether too difficult for him. If the transfrontier barbarian is a more brutal, as well as a more sophisticated, being than his primitive ancestor, the latter-day barbarian who has broken through the frontier and carved a successor-state out of the derelict domain of the defunct empire becomes much more demoralized than before. While the limes

still stood, his orgies of idleness spent in consuming the loot of a successful raid had to be paid for with the hardships and rigours of defence against the punitive expedition that his raid was bound to provoke; with the limes

broken down, orgies and idleness could be prolonged with impunity. As we observed in an earlier part of this Study, the barbarians in partibus civilium

condemned themselves to the sordid role of vultures feeding on carrion or maggots crawling in a carcass. If these comparisons appear too brutal, we may liken the hordes of triumphant barbarians running amok amid the ruins of a civilization which they cannot appreciate to the gangs of vicious adolescents who had escaped the controls of home and school and were among the problems of overgrown urban communities in the twentieth century of the Christian Era.

‘The qualities exhibited by these societies, virtues and defects alike, are clearly those of adolescence. … The characteristic feature … is emancipation—social, political, and religious—from the bonds of tribal law. … The characteristics of heroic ages in general are those neither of infancy nor of maturity…. The typical man of the Heroic Age is to be compared rather with a youth. … For a true analogy we must turn to the case of a youth who has outgrown both the ideas and the control of his parents—such a case as may be found among the sons of unsophisticated parents who, through outside influence, at school or elsewhere, have acquired knowledge which places them in a position of superiority to their surroundings.’

1

One of the results of the decadence of primitive custom among primitive-turned-barbarian peoples is that the power formerly exercised by kindred-groups is transferred to the comitatus

, a body of individual adventurers pledged to personal loyalty to a chief. So long as a civilization maintained within its universal state a semblance of authority, such barbarian war-lords and their comitatus

could, on occasion, perform with success the service of providing buffer states. The history of the Salian Frankish guardians of the Roman Empire’s Lower Rhenish frontier from the middle of the fourth to the middle of the fifth century of the Christian Era may be adduced as one of many examples of this state of affairs. But the fates of successor-states established by barbarian conquerors

in the interior of an extinct universal state’s former domain show that this coarse product of a jejune barbarian political genius was quite unequal to the task of bearing burdens and solving problems that had already proved too much for the statesmanship of an œcumenical Power. A barbarian successor-state blindly goes into business on the strength of the dishonoured credits of a bankrupt universal state, and these boors in office hasten the advent of their inevitable doom by a self-betrayal through the outbreak, under stress of a moral ordeal, of something fatally false within; for a polity based solely on the fickle loyalty of a gang of armed desperadoes to an irresponsible military leader is morally unfit for the government of a community that has made even an unsuccessful attempt at civilization. The dissolution of the primitive kingroup in the barbarian comitatus

is swiftly followed by the dissolution of the comitatus

itself in the alien subject population.

The barbarian trespassers in partibus civilium

have, in fact, condemned themselves to suffer a moral breakdown as an inevitable consequence of their trespass, yet they do not yield to their fate without a spiritual struggle that has left its traces in their literary records of myth and ritual and standards of conduct. The barbarians’ ubiquitous master-myth describes the hero’s victorious fight with a monster for the acquisition of a treasure which the unearthly enemy is withholding from Mankind. This is the common motif

of the tales of Beowulf’s fight with Grendel and Grendel’s mother; Siegfried’s fight with the dragon; and Perseus’ feat of decapitating the Gorgon and his subsequent feat of winning Andromeda by slaying the sea-monster who was threatening to devour her. The motif

reappears in Jason’s outmanoeuvring of the serpent-guardian of the Golden Fleece and in Herakles’ kidnapping of Cerberus. This myth looks like a projection, on to the outer world, of a psychological struggle, in the barbarian’s own soul, for the rescue of Man’s supreme spiritual treasure, his rational will, from a demonic spiritual force released in the subconscious depths of the Psyche by the shattering experience of passing, at one leap, from a familiar no-man’s-land outside the limes

into the enchanted world laid open by the barrier’s collapse. The myth may, indeed, be a translation into literary narrative of a ritual act of exorcism in which a militarily triumphant but spiritually afflicted barbarian has attempted to find a practical remedy for his devastating psychological malady.

In the emergence of special standards of conduct applicable to the peculiar circumstances of an heroic age we can see a further attempt, from another line of approach, to set moral bounds to the ravages of a demon that has been let loose in the souls of barbarian

lords and masters of a prostrate civilization by the fall of the material barrier of the limes

. Conspicuous examples are the Achaeans’ Homeric Aidôs

and Nemesis

(’Shame’ and ‘Indignation’) and the Umayyads’ historic Hilm

(a studied self-restraint).

‘The great characteristic of [Aidôs

and Nemesis]

, as of Honour generally, is that they only come into operation when a man is free: when there is no compulsion. If you take people … who have broken away from all their old sanctions and select among them some strong and turbulent chief who fears no one, you will first think that such a man is free to do whatever enters his head. And then, as a matter of fact, you find that, amid his lawlessness, there will crop up some possible action which somehow makes him feel uncomfortable. If he has done it, he ‘rues’ the deed and is haunted by it. If he has not done it, he ‘shrinks’ from doing it. And this, not because anyone forces him, nor yet because any particular result will accrue to him afterwards, but simply because he feels Aidôs

….

‘Aidôs

is what you feel about an act of your own; Nemesis

is what you feel for the act of another. Or, most often, it is what you imagine that others will feel about you…. But suppose no one sees. The act, as you know well, remains  —a thing to feel Nemesis

about: only there is no one there to feel it. Yet, if you yourself dislike what you have done, and feel Aidôs

for it, you inevitably are conscious that somebody or something dislikes or disapproves of you. … The Earth, Water, and Air [are] full of living eyes: of theoi

, of daimones

, of kêres…

. And it is they who have seen you and are wroth with you for the thing which you have done.’

1

—a thing to feel Nemesis

about: only there is no one there to feel it. Yet, if you yourself dislike what you have done, and feel Aidôs

for it, you inevitably are conscious that somebody or something dislikes or disapproves of you. … The Earth, Water, and Air [are] full of living eyes: of theoi

, of daimones

, of kêres…

. And it is they who have seen you and are wroth with you for the thing which you have done.’

1

In a post-Minoan heroic age, as depicted in the Homeric Epic, the actions that evoke feelings of Aidôs

and Nemesis

are those implying cowardice, lying, and perjury, lack of reverence, and cruelty or treachery towards the helpless.

‘Apart from any question of wrong acts done to them, there are certain classes of people more  objects of Aidôs

, than others. There are people in whose presence a man feels shame, self-consciousness, awe, a sense keener than usual of the importance of behaving well. And what sort of people chiefly excite this Aidîs

? Of course there are kings, elders and sages, princes and ambassadors:

objects of Aidôs

, than others. There are people in whose presence a man feels shame, self-consciousness, awe, a sense keener than usual of the importance of behaving well. And what sort of people chiefly excite this Aidîs

? Of course there are kings, elders and sages, princes and ambassadors:  and the like: all of them people for whom you naturally feel reverence, and whose good or bad opinion is important in the World. Yet … you will find that it is not these people, but quite others, who are most deeply charged, as it were, with Aidôs

… before whom you feel still more keenly conscious of your unworthiness, and whose good or ill opinion weighs somehow inexplicably more in the last account: the disinherited of the Earth, the injured, the helpless, and, among them the most utterly helpless of all, the dead.’

2

and the like: all of them people for whom you naturally feel reverence, and whose good or bad opinion is important in the World. Yet … you will find that it is not these people, but quite others, who are most deeply charged, as it were, with Aidôs

… before whom you feel still more keenly conscious of your unworthiness, and whose good or ill opinion weighs somehow inexplicably more in the last account: the disinherited of the Earth, the injured, the helpless, and, among them the most utterly helpless of all, the dead.’

2

In contrast to Aidôs

and Nemesis

, which enter into all aspects of social life, Hilm

is a vertu des politiques

.

1

It is something more sophisticated than Aidôs

and Nemesis

, and consequently less attractive. Hilm

is not an expression of humility;

‘its aim is rather to humiliate an adversary: to confound him by presenting the contrast of one’s own superiority; to surprise him by displaying the dignity and calm of one’s own attitude…. At bottom, Hilm

, like most Arab qualities, is a virtue for bravado and display, with more ostentation in it than real substance. … A reputation for Hilm

can be acquired at the cheap price of an elegant gesture or a sonorous mot..

, opportune above all in an anarchic milieu

, such as the Arab society was, where every act of violence remorselessly provoked a retaliation. … Hilm

, as practised by [Mu‘āwīyah’s Umayyad successors], facilitated their task of giving the Arabs a political education; it sweetened for their pupils the bitterness of having to sacrifice the anarchic liberty of the Desert in favour of sovereigns who were condescending enough to draw a velvet glove over the iron hand with which they ruled their empire.’

2

These masterly characterizations of the nature of Hilm, Aidôs

, and Nemesis

show how nicely adapted these standards of conduct are to the peculiar circumstances of the Heroic Age; and, if, as we have intimated already, the Heroic Age is, intrinsically, a transient phase, the surest signs of its advent and its recession are the epiphany and the eclipse of its specific ideals. As Aidôs

and Nemesis

fade from view, their disappearance evokes a cry of despair. ‘Pain and grief are the portion that shall be left for mortal men, and there shall be no defence against the evil day.’

3

Hesiod is harrowed by his illusory conviction that the withdrawal of these glimmering lights that have sustained the children of the Dark Age is a portent of the onset of perpetual darkness; he has no inkling that this extinguishing of the night-lights is a harbinger of the return of day. The truth is that Aidôs

and Nemesis

reascend to Heaven as soon as the imperceptible emergence of a nascent new civilization has made their sojourn on Earth superfluous by bringing into currency other virtues that are socially more constructive though aesthetically they may be less attractive. The Iron Age into which Hesiod lamented that he had been born was in fact the age in which a living Hellenic civilization was arising out of a dead Minoan civilization’s ruins; and the ‘Abbasids, who had no use for the

Hilm

that had been their Umayyad predecessors’ arcanum imperii

, were the statesmen who set the seal on the Umayyad’s tour de force

of profiting by the obliteration of the Syrian limes

of the Roman Empire in order to reinaugúrate the Syriac universal state.

The demon who takes possession of the barbarian’s soul as soon as the barbarian’s foot has crossed the fallen limes

is indeed difficult to exorcise, because he contrives to pervert the very virtues with which his victim has armed himself. One might well say of Aides

what Madame Roland said of Liberty: ‘What crimes have been committed in thy name!’ The barbarian’s sense of honour ‘roars like a rapacious beast that never knows when it has had its fill’.

1

Wholesale atrocities are the outstanding features of the Heroic Age, both in history and in legend. The demoralized barbarian society in which these dark deeds are perpetrated is so familiar with their performance and so obtuse to their horror that the bards whose task it is to immortalize the memory of the warlords do not hesitate to saddle their heroes and heroines with sins of which they may well have been innocent, when a blackening of their characters will magnify their prowess. Nor is it only against their official enemies that the Heroes perform their appalling atrocities. The horrors of the Sack of Troy are surpassed by the horrors of the family feud of the House of Atreus. ‘Houses’ thus divided against themselves are not likely to stand for long.

A sensationally sudden fall from an apparent omnipotence is, indeed, the characteristic fate of an heroic-age barbarian Power. Striking historical examples are the eclipse of the Huns after the death of Attila, and that of the Vandals after the death of Genseric. These and other historically attested examples lend credibility to the tradition that the wave of Achaean conquest likewise broke and collapsed after engulfing Troy, and that a murdered Agamemnon was the last Pan-Achaean war-lord. However widely these warlords might extend their conquests, they were incapable of creating institutions. The fate of the empire of even so sophisticated and comparatively civilized a war-lord as Charlemagne provides a dramatic illustration of this incapacity.

(4) FANCY AND FACT

If there is truth in the picture presented in the preceding chapter, the verdict on the Heroic Age can only be a severe one. The mildest judgement will convict it of having been a futile

escapade, while sterner judges will denounce it as a criminal outrage. The verdict of futility makes itself heard through the mellow poetry of a Victorian man of letters who had lived on to feel the frost of a neo-barbarian age.

Follow the path of those fair warriors, the tall Goths

from the day when they led their blue-eyed families

off Vistula’s cold pasture-lands, their murky home

by the amber-strewen foreshore of the Baltic sea,

and, in the incontaminat vigor of manliness

feeling their rumour’d way to an unknown promised land,

tore at the ravel’d fringes of the purple power,

and trampling its wide skirts, defeating its armies,

slaying its Emperor, and burning his cities

sack’d Athens and Rome; untill supplanting Caesar

they ruled the world where Romans reigned before:—

Yet from those three long centuries of rapin and blood,

inhumanity of heart and wanton cruelty of hand,

ther is little left. … Those Goths wer strong but to destroy;

they neither wrote nor wrought, thought not nor created;

but, since the field was rank with tares and mildew’d wheat,

their scything won some praise: Else have they left no trace.

1

This measured judgement, delivered across a gulf of fifteen centuries, could hardly have satisfied an Hellenic poet who was bitterly conscious of still living in a moral slum made by barbarian successors of the ‘thalassocracy of Minos’. Criminality, and not mere futility, is the burden of Hesiod’s indictment against a post-Minoan heroic age that, in his day, was still haunting a nascent Hellenic civilization. His judgement is merciless.

‘And Father Zeus made yet a third race of mortal men—a Race of Bronze, in no wise like unto the Silver, fashioned from ash-stems, mighty and terrible. Their delight was in the grievous deeds of Ares and in the trespasses of Pride  No bread ever passed their lips, but their hearts in their breasts were strong as adamant, and none might approach them. Great was their strength and unconquerable were the arms which grew from their shoulders upon their stalwart frames. Of bronze were their panoplies, of bronze their houses, and with bronze they tilled the land (dark iron was not yet). These were brought low by their own hands and went their way to the mouldering house of chilly Hades, nameless. For all their mighty valour, Death took them in his dark grip, and they left the bright light of the Sun.’

2

No bread ever passed their lips, but their hearts in their breasts were strong as adamant, and none might approach them. Great was their strength and unconquerable were the arms which grew from their shoulders upon their stalwart frames. Of bronze were their panoplies, of bronze their houses, and with bronze they tilled the land (dark iron was not yet). These were brought low by their own hands and went their way to the mouldering house of chilly Hades, nameless. For all their mighty valour, Death took them in his dark grip, and they left the bright light of the Sun.’

2

In Posterity’s judgement on the overflowing measure of suffering

which the barbarians bring on themselves by their own criminal follies, this passage in Hesiod’s poem might have stood as the last word, had not the poet himself run on as follows:

‘Now when this race also had been covered by Earth, yet a fourth race was made, again, upon the face of the All-Mother, by Zeus son of Cronos—a better race and more righteous, a divine race of men heroic, who are called demigods, a race that was aforetime on the boundless Earth. These were destroyed by evil War and dread Battle—some below Seven-Gate Thebes in the land of Cadmus, as they fought for the flocks of Oedipus, while others were carried for destruction to Troy in ships over the great gulf of the sea, for the sake of Helen of the lovely hair. There verily they met their end and vanished in the embrace of Death; yet a few there were who were granted a life and a dwelling-place, apart from Mankind, by Zeus son of Cronos, who made them to abide at the ends of the Earth. So there they abide, with hearts free from care, in the Isles of the Blessed, beside the deep eddies of Ocean Stream—happy heroes, for whom a harvest honey-sweet, thrice ripening every year, is yielded by fruitful fields.’

1

What is the relation of this passage to the one which immediately precedes it, and indeed to the whole catalogue of races in which it is imbedded? The episode breaks the sequence of the catalogue in two respects. In the first place the race here passed in review, unlike the preceding races of gold, silver, and bronze and the succeeding race of iron, is not identified with any metal; and, in the second place, all the other four races are made to follow one another in a declining order of merit. Moreover, the destinies of the three preceding races after death are consonant with the tenour of their lives on Earth. The Race of Gold ‘became good spirits by the will of great Zeus—spirits above

the ground, guardians of mortal men, givers of wealth’. The inferior Race of Silver still ‘gained among mortals the name of blessed ones beneath

the ground—second in glory; and yet, even so, they too are attended with honour’. When we come, however, to the Race of Bronze, we find that their fate after death is passed over in ominous silence. In a catalogue woven on this pattern we should expect to find the fourth race condemned after death to suffer the torments of the damned; yet, so far from that, we find at least a chosen few of them transported after death to Elysium, where they live, above ground, the very life that had been lived by the Race of Gold.

Manifestly the insertion of a Race of Heroes between the Race of Bronze and the Race of Iron is an afterthought, breaking the poem’s sequence, symmetry, and sense. What moved the poet to make this clumsy insertion? The answer must be that the

picture here presented of a Race of Heroes was so vividly impressed on the imagination of the poet and his public that a place had to be found for it. The Race of Heroes, is, in fact, the Race of Bronze described over again, in terms, not of sombre Hesiodic fact, but of glamorous Homeric fancy.

In social terms the Heroic Age is a folly and a crime, but in emotional terms it is a great experience, the thrilling experience of breaking through the barrier which has baffled the barbarian invaders’ ancestors for generations, and bursting out into an apparently boundless world that offers what seem to be infinite possibilities. With one glorious exception, all these possibilities turn out to be Dead Sea fruit; yet the sensational completeness of the barbarians’ failure on the social and political planes paradoxically ministers to the success of their bards’ creative work, for in art there is more to be made out of failure than out of success; no ‘success story’ can achieve the stature of a tragedy. The exhilaration generated by the Völkerwanderung, which breaks down into demoralization in the intoxicated souls of the men of action, inspires the barbarian poet to transmute the memory of his heroes’ wickedness and ineptitude into immortal song. In the enchanted realm of this poetry the barbarian conquistadores

achieve vicariously the splendour that eluded their grasp in real life. Dead history blossoms into immortal romance. The fascination exercised by heroic poetry over its latter-day admirers deludes them into vizualizing what was in fact a sordid interlude between the death of one civilization and the birth of its successor as—what we have called it, not without intentional irony, in the terminology of this Study—an Heroic Age, an Age of Heroes.

The earliest victim of this illusion is, as we have seen, the poet of a ‘Dark Age’, which is the ‘Heroic Age’s’ sequel. As is manifest in retrospect, this later age has no reason to be ashamed of a darkness which signifies that the barbarian incendiaries’ bonfires have at last burnt themselves out; and, though a bed of ashes smothers the surface of the flame-scarred ground, the Dark Age proves to be creative, as the Heroic Age certainly was not. In the fullness of time, new life duly arises to clothe the fertile ash-field with shoots of tender green. The poetry of Hesiod, so pedestrian when set beside that of Homer, is one of these harbingers of a returning spring-time; yet this honest chronicler of the darkness before the dawn is still so bedazzled with a poetry inspired by the recent nocturnal incendiarism that he takes on faith, as historical truth, an imaginary Homeric picture of a Race of Heroes.

Hesiod’s illusion seems strange, considering that, in his picture of the Race of Bronze, he has preserved for us, side by side with

his reproduction of an Homeric fantasy, a merciless exposure of the barbarian as he really is. Yet, even without this clue, the heroic myth can be exploded by detonating the internal evidence. The Heroes turn out to have lived the evil lives and died the cruel deaths of the Race of Bronze, and Valhalla likewise turns out to be a slum when we switch off all the artificial lights and scrutinize by the sober light of day this poetic idealization of turbulent fighting and riotous feasting. The warriors who qualify for admission to Valhalla are in truth identical with the demons against whom they have exercised their prowess; and, in perishing off the face of the Earth by mutual destruction, they have relieved the World of a pandemonium of their own making and have achieved a happy ending for everyone but themselves.

Hesiod may have been the first, but he was by no means the last, to be beguiled by the splendours of barbarian epic. In a supposedly enlightened nineteenth century of the Christian Era we find a philosopher-mountebank launching his myth of a salutary barbarian ‘Nordic Race’ whose blood acts as an elixir of youth when injected into the veins of an ‘effete society’; and we may still be cut to the heart as we watch the lively French aristocrat’s political jeu d’esprit

being keyed up into a racial myth by the prophets of a demonic German Neobarbarism. Plato’s insistence that poets should be banished from his Republic gains a vivid significance as we trace the line of cause and effect between the authors of the Sagas and the founders of the Third Reich.

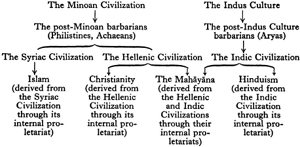

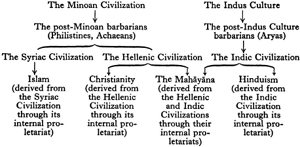

Yet there have been occasions when the barbarian interloper has performed, after all, a humble service for Posterity. At the transition from the civilizations of the first generation to those of the second, the interloping barbarians did in some cases provide a link between the defunct civilization and its newborn successor, as, in the subsequent transition from the second generation to the third, a link was provided by the chrysalis-churches. The Syriac and Hellenic civilizations, for instance, were thus linked with an antecedent Minoan civilization through this Minoan society’s external proletariat, and the Hittite civilization stood in the same relation to an antecedent Sumeric civilization, and the Indic civilization to an antecedent Indus culture (if, in fact, this last had a life of its own that was independent of the Sumeric civilization). The modesty of the service thus performed is brought out by comparing it with the role of the chrysalis-churches. While the internal proletariat that builds churches, like the external proletariat that breeds war-bands, is the offspring of a psychological secession from a disintegrating civilization, the internal proletariat obviously acquires and hands on to future generations a far richer heritage of

the past. This becomes obvious if we compare the debt of the Western Christian civilization to the Hellenic with the debt of the Hellenic civilization to the Minoan. The Christian Church was hellenized to saturation-point; the Homeric poets knew next to nothing of Minoan society: they present their Heroic Age in vacuo

, with no more than a casual reference to the mighty carcass on which the bard’s vulture-heroes—’sackers of cities’ as they are proud to call themselves—are making their carrion-feasts.

On this showing, the service of the Achaeans and the other barbarians of their generation who played the same transmissive role might seem to dwindle to vanishing-point. What did it really amount to? Its reality becomes evident when we compare the destinies of those civilizations of the second generation that were affiliated to predecessors by this tenuous barbarian link with the destinies of the rest of the secondary civilizations. Any secondary civilization not affiliated through its predecessor’s external proletariat must have been affiliated through its predecessor’s dominant minority. These are the only alternatives, since no chrysalis-churches came out of the rudimentary higher religions of the internal proletariats of the primary civilizations.

We have, then, two groups of civilizations of the second generation, those affiliated to their predecessors through external proletariats and those affiliated through their predecessors’ dominant minorities, and in other respects also these two groups stand at opposite poles. The former group are so distinct from their predecessors that the very fact of affiliation becomes dubious. The latter are so closely linked with their predecessors that their claims to separate existence may be disputed. The three known examples of the latter group are the Babylonic, which may be regarded either as a separate civilization or as an extension of the Sumeric, and the Yucatec and the Mexic, which are similarly related to the Mayan. Having sorted out these two groups, we may go on to observe another difference between them. The group of supra-affiliated secondary civilizations (or dead trunks of primary civilizations) all failed, where civilizations of the other group—the Hellenic, the Syriac, the Indic—succeeded; none of the super-affiliated civilizations gave birth, before its own expiry, to a universal church.

If we call to mind our conclusion that our serial order of chronologically successive types of society is at the same time an ascending order of value, in which the higher religions would be the highest term so far attained, we shall now observe that the barbarian chrysalises of civilizations of the second generation (but not those of the third) would have to their credit the honour of having participated

in the higher religions’ evolution. The proposition can be conveyed most clearly by means of the following table:

NOTE: ‘THE MONSTROUS REGIMENT OF WOMEN’

THE

Heroic Age might have been expected to be a masculine age par excellence

. Does not the evidence convict it of having been an age of brute force? And, when force is given free rein, what chance can women have of holding their own against the physically dominant sex? This a priori

logic is confuted, not only by the idealized picture presented in heroic poetry, but also by the facts of history.

In the Heroic Age the great catastrophes are apt to be women’s work, even when the woman’s role is ostensibly passive. If Alboin’s unsatisfied desire for Rosamund was the cause of the extermination of the Gepidae, it is credible that the sacking of Troy was provoked by the satisfaction of Paris’s desire for Helen. More commonly the women are undisguisedly the mischief-makers whose malice drives the heroes into slaying each other. The legendary quarrel between Brunhild and Kriemhild, which eventually discharged itself in the slaughter in Etzel’s Danubian hall, is all of a piece with the authentic incidents of the quarrel between the historic Brunhild and her enemy Fredegund, which cost the Merovingian successor-state of the Roman Empire forty years of civil war.

The influence of women over men in the Heroic Age was not, of course, exhibited solely in the malevolence of goading their menfolk into fratricidal strife. No women left deeper marks on history than Alexander’s mother, Olympias, and Mu‘āwīyah’s mother Hind, both of whom immortalized themselves by their lifelong moral ascendancy over their redoubtable sons. Yet a list of Gonerils, Regans, and Lady Macbeths, culled from the records of authenticated history, could be indefinitely prolonged. There are perhaps two lines of explanation of this phenomenon, one sociological and the other psychological.

The sociological explanation is to be found in the fact that the Heroic Age is a social interregnum in which the traditional habits of primitive life have been broken up, while no new ‘cake of custom’ had yet been

baked by a nascent civilization or a nascent higher religion. In this ephemeral situation a social vacuum is filled by an individualism so absolute that it overrides the intrinsic differences between the sexes. It is remarkable to find this unbridled individualism bearing fruits hardly distinguishable from those of a doctrinaire feminism altogether beyond the emotional range and the intellectual horizon of the women and men of such periods. Approaching the problem on the psychological side, it may be suggested that the winning cards in the barbarians’ internecine struggles for existence are not brute force but persistence, vindictiveness, implacability, cunning, and treachery; and these are qualities with which sinful human nature is as richly endowed in the female as in the male.

If we ask ourselves whether these women who exercise their ‘monstrous regiment’ in the inferno of the Heroic Age are heroines or villainesses or victims, we shall arrive at no clear answer. What is plain is that their tragic moral ambivalence makes them ideal subjects for poetry; and it is not surprising that, in the epic legacy of a post-Minoan heroic age, one of the favourite genres

should have been ‘catalogues of women’, in which the recital of one legendary virago’s crimes and sufferings called up the legend of another, in an almost endless chain of poetic reminiscence. The historic women whose grim adventures echo through this poetry would have smiled, with wry countenances, could they have foreknown that a reminiscence of a reminiscence would one day evoke A Dream of Fair Women

in the imagination of a Victorian poet. They would have felt decidedly more at home in the atmosphere of the third scene in the first act of Macbeth

.

—a thing to feel Nemesis

about: only there is no one there to feel it. Yet, if you yourself dislike what you have done, and feel Aidôs

for it, you inevitably are conscious that somebody or something dislikes or disapproves of you. … The Earth, Water, and Air [are] full of living eyes: of theoi

, of daimones

, of kêres…

. And it is they who have seen you and are wroth with you for the thing which you have done.’

1

—a thing to feel Nemesis

about: only there is no one there to feel it. Yet, if you yourself dislike what you have done, and feel Aidôs

for it, you inevitably are conscious that somebody or something dislikes or disapproves of you. … The Earth, Water, and Air [are] full of living eyes: of theoi

, of daimones

, of kêres…

. And it is they who have seen you and are wroth with you for the thing which you have done.’

1

objects of Aidôs

, than others. There are people in whose presence a man feels shame, self-consciousness, awe, a sense keener than usual of the importance of behaving well. And what sort of people chiefly excite this Aidîs

? Of course there are kings, elders and sages, princes and ambassadors:

objects of Aidôs

, than others. There are people in whose presence a man feels shame, self-consciousness, awe, a sense keener than usual of the importance of behaving well. And what sort of people chiefly excite this Aidîs

? Of course there are kings, elders and sages, princes and ambassadors:  and the like: all of them people for whom you naturally feel reverence, and whose good or bad opinion is important in the World. Yet … you will find that it is not these people, but quite others, who are most deeply charged, as it were, with Aidôs

… before whom you feel still more keenly conscious of your unworthiness, and whose good or ill opinion weighs somehow inexplicably more in the last account: the disinherited of the Earth, the injured, the helpless, and, among them the most utterly helpless of all, the dead.’

and the like: all of them people for whom you naturally feel reverence, and whose good or bad opinion is important in the World. Yet … you will find that it is not these people, but quite others, who are most deeply charged, as it were, with Aidôs

… before whom you feel still more keenly conscious of your unworthiness, and whose good or ill opinion weighs somehow inexplicably more in the last account: the disinherited of the Earth, the injured, the helpless, and, among them the most utterly helpless of all, the dead.’ No bread ever passed their lips, but their hearts in their breasts were strong as adamant, and none might approach them. Great was their strength and unconquerable were the arms which grew from their shoulders upon their stalwart frames. Of bronze were their panoplies, of bronze their houses, and with bronze they tilled the land (dark iron was not yet). These were brought low by their own hands and went their way to the mouldering house of chilly Hades, nameless. For all their mighty valour, Death took them in his dark grip, and they left the bright light of the Sun.’

No bread ever passed their lips, but their hearts in their breasts were strong as adamant, and none might approach them. Great was their strength and unconquerable were the arms which grew from their shoulders upon their stalwart frames. Of bronze were their panoplies, of bronze their houses, and with bronze they tilled the land (dark iron was not yet). These were brought low by their own hands and went their way to the mouldering house of chilly Hades, nameless. For all their mighty valour, Death took them in his dark grip, and they left the bright light of the Sun.’