Bookbinding

DAVID PEARSON

Books have needed outer covers and a means of holding them together for as long as they have existed, partly to keep their pages in the intended order, and partly to provide protection. Bookbinding embraces all the techniques that have evolved to achieve these ends, including the materials and structures employed, and the many ways in which the covers have been decorated. It is a subject of study in its own right, with an extensive literature; bookbindings have been admired and collected for their artistic qualities, but their intrinsic interest goes beyond this. Before mechanization was introduced in the 19th century, all bookbindings were individually handmade objects and the choices exercised in deciding how elaborate or simple a binding should be became part of the history of every book. The introduction of paperback binding, coupled with rising exploitation of the pictorial possibilities of outer covers, is a significant element in modern publishing history and in the dissemination of books to ever greater markets during the 20th century.

Papyrus, which could be glued together into long scrolls that might be stored in protective wooden cases, was the preferred writing medium in ancient Egypt and its use spread across the Graeco-Roman world during the pre-Christian era (see 3). The codex—the form of the book as we know it—emerged from this tradition during the first few centuries AD when leaves of papyrus began to be folded and sewn into leather covers. Structures like this, originating in the near east, known from the 2nd century, are particularly associated with the emerging Christian sects; they gradually replaced scrolls as the preferred method for recording and storing texts during the succeeding centuries.

The Roman statesman Cassiodorus (c.490–c.580), in his Institutiones (written c.560), refers to bookbinders trained to produce bindings in various styles, and an 8th-century English MS illustration is generally believed to depict him with his nine-volume Bible, bound as recognizable codices with decorated covers. The Stonyhurst Gospel, made c.700, is the oldest surviving European decorated binding; with folded and sewn quires, covered with decorated leather over boards, it brings together essential characteristics that would remain constant in bookbinding practice for the following millennium and more.

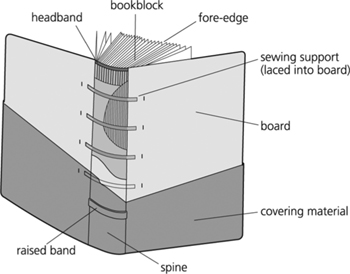

Most bookbindings made in Europe between c.800 (when the sewing style developed) and 1800 conform structurally to a standard model, sometimes called flexible sewing. The leaves are folded into gatherings which are sewn through the central folds on to a number of supports running horizontally across these folded edges. The projecting ends of the supports are laced and secured into stiff boards, which are then covered with an outer skin (typically leather or parchment, but possibly paper or fabric); this is decorated to create the finished product. Additional leaves (endleaves) are commonly added at each end of the text block before attaching the boards; the spine is rounded; endbands may be added at head and foot; and the leaf edges are trimmed with a sharp blade (sometimes called a plough) to create an even surface. In bookbinding terminology, the construction stages are known as forwarding, and the decoration as finishing.

The basic structural features of a European bookbinding in the medieval and hand press periods. Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators

These processes remained essentially constant throughout the medieval and handpress periods; the relatively few changes that evolved over time were commonly associated with a wish to expedite or economize on labour and materials as more books came to be produced. Once printing was established, the double-thickness sewing supports typically used in medieval bindings gave way to single ones, and various techniques were developed to speed up sewing by running the needle between gatherings as it ran up and down the spine. An alternative practice widely used for pamphlets and temporary, cheap bindings was stabbing and stab-stitching, running a thread through the whole text block near the spine edge.

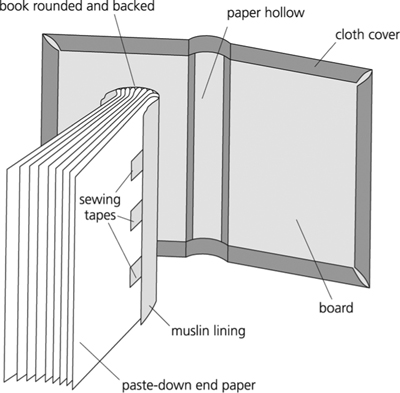

Bookbinding practices, like all other aspects of the book-production and distribution industries, underwent major changes during the 19th century. Towards the end of the 18th century, rising leather costs, combined with ever-growing book production, led to greater experimentation with cloth and paper as alternative materials. During the 1820s and 1830s, books were increasingly issued with cloth-covered boards, secured to the text block using glued strips of canvas, rather than laced-in sewing supports. Cloth covers, decorated and lettered, could be prefabricated and case binding quickly became established as the standard technique. Whole editions of books therefore began to be issued in identical bindings, another major change from the practice of the handpress era.

These essential structural features of casebound books have continued largely unchanged to the present time, although the processes involved have undergone progressive mechanization (see section 8, below). While many ‘hard-back’ books still conform to this style, modern books often rely on glue rather than sewing to hold them together, an alternative (and cheaper) binding technique that dates back to 1836 when William Hancock was granted a patent for what were then called caoutchouc bindings. After gathering the text block in the usual way, the spine folds were cut off (leaving each leaf a singleton, not attached to any other) before being coated with a flexible rubber solution that when set held all the leaves together. As the rubber perished over time, the leaves fell out, and the technique was largely abandoned commercially around 1870. It was revived in the 20th century and the introduction of new thermoplastic glues from about 1950 onwards led to increased production of what are variously called unsewn or perfect bindings, much used particularly for paperback books. The failure of the glue over time remains a problem, and bindings based on sewing continue to provide the strongest and most permanent structures.

Diagram of the structural features of a modern casebound book ready for casing in (adapted from Gaskell, NI). Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators

The earliest codex bindings, from North Africa and the surrounding area, followed a different sewing technique using a chain stitch sewn across the gatherings, instead of running the thread up and down the quires. This method, sometimes called Coptic sewing, was initially used across Europe, but was abandoned there in favour of flexible sewing around the beginning of the 9th century. The Coptic method continued to be used in the Near East, including the Byzantine and Islamic cultures where bookbinding flourished throughout the Middle Ages and beyond. Coptic sewing produces books that open well, but whose spines tend to become concave over time, and whose board attachment may be weaker than that produced by Western methods of laced-in supports.

Coptic sewing differs from western flexible sewing technique in that the quires are sewn together with a chain stitch, rather than being sewn on to separate sewing supports run across the spine. Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators

In Asia, a variety of binding styles developed, influenced by the shapes and characteristics of the writing materials. In India and other parts of Southeast Asia, palm leaves, cut into long thin strips, were commonly held together with string passed through holes in each leaf, fastened at each end to a wooden cover; this pothi format, an ancient tradition, remained in common use down to the 19th century (see 41). Chinese and Japanese binding (see 42, 44) evolved differently, following the invention of paper in China around AD 100 and its widespread adoption for documentary purposes (although bamboo and wood, in thin strips tied together, were also used, and pothi-type structures using paper leaves are known in China from the 7th century onwards).

The Chinese made extensive use of scrolls during the first millennium AD and their earliest printed books (using block printing) were scroll-based, like the Diamond Sutra (dated to 868). The concertina format, made by pasting sheets together in one long continuous sequence, but folding it rather than rolling so as to create a rectangular book-shaped object when closed, was a natural evolution from the scroll, and began to emerge during the Tang dynasty (618–907). During the Song dynasty (960–1279), scroll-based formats were increasingly replaced by ones based on folded leaves, more like Western book structures. Various kinds of stitching techniques are known to have been used, as well as paste-based ones such as butterfly binding, in which single bifolia are pasted together at the spine fold. The bifolia would typically be printed or written on one side only, leaving alternate blank openings corresponding to the pasted folds. By folding the other way, and binding along the open edge rather than the folded one, it was possible to create a book of continuous text without blanks, and it was this development, together with the emergence of new sewing methods, around the 12th–14th centuries that led to the format most commonly recognized today as a typical oriental binding. Sometimes called four-hole binding or Japanese binding (although it developed in China), such books are sewn through the open folds that make the spine edge, stabbing through the whole text block and running the thread over the head and tail as well as round the back. This format became established during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and has continued in use, although Western bookbinding methods also became increasingly common in East Asia after the 19th century.

Thread, four-hole, or Japanese binding: this characteristic binding format developed in China during the Ming period and has been extensively used in East Asia. Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators

In European practice, leather-covered boards were the typical choice, over many centuries, for bindings intended to be permanent. From the earliest times to the end of the Middle Ages, boards were usually made of wood (in England, oak or beech), cut in thin slices with the grain running parallel to the spine. During the 16th century, wood was gradually replaced by pasteboard and other paper-based boards, being both lighter and cheaper, as books became smaller and more numerous. Millboard (made from waste hemp materials) was introduced in the 17th century and strawboard (based on pulped straw) in the 18th. Modern bookbindings typically use some kind of machine-made paper-based cardboard. Medieval bindings commonly had metal clasps across their edges to prevent the vellum leaves from cockling, a tradition which died out (other than for ornamental purposes) during the 16th and 17th centuries as pasteboard and paper replaced wood and vellum.

Leather used for bookbinding has come from a range of animals, prepared in different ways. Leather is made from animal skins either by tanning—treating the dehaired skin with tannic acid—or tawing, when the chemical used is potassium aluminium sulphate (alum). The former creates a smoother, harder leather which can take and retain impressed decoration. Medieval bookbinders typically used tawed leather, made not only from domestic animals but from deer-skin and sealskin. In most European countries, tanned leather replaced tawed for bookbinding during the 15th century, although tawed pigskin continued to be popular in and around Germany into the 17th century.

Tanned calfskin, dyed a shade of brown, is the covering material most commonly found on post-medieval British bindings. Calf produced a durable but lightweight leather, with a smooth and pleasing surface. Tanned sheepskin, which has a coarser grain and is less hard-wearing, was used for cheaper work. Tanned goatskin was the leather of choice for the best-quality bindings; it was increasingly used in Europe from the 16th century onwards, having been developed for bookbinding by Islamic craftsmen in the Near East well before then. Most of the goatskin used in England during the hand press period was imported from Turkey or Morocco and, hence, was commonly called ‘Turkey’ or ‘Morocco’.

Vellum or parchment, made by soaking calfskin or sheepskin and drying it under tension, without chemical tanning, was also extensively used as a covering material in early modern Europe, often for cheaper bindings when a vellum wrapper, without boards, might provide sufficient protection for a pamphlet or small book. In Britain, the use of vellum for binding work dwindled after the mid-17th century, except for stationery binding, but it continued to be much used in Germany and the Low Countries well into the 18th century. Paper, or paper over thin boards, was also sometimes used for cheap or temporary bindings, and this practice increased as time progressed; there are a few extant examples of printed-paper wrappers from the early centuries of printing (there must once have been very many more, which have perished), but 18th-century pamphlets in wrappers of blue or marbled paper are relatively common. Towards the end of that century books increasingly came to be issued in paper-covered boards, a trend that continued throughout the 19th century with a growth in printed paper covers. During the hand press period, paper or card-based binding options were generally more common in continental Europe than in Britain; wrappers of rough plain card (sometimes called cartonnage) began to be used in Italy during the 16th century and can also be found from France or Germany around that time and later.

The use of fabric as a covering material dates back to medieval times, originally as a luxury option, using velvet or embroidered textiles. Many elaborately decorated velvet bindings from the 16th and 17th centuries survive, and in early 17th-century England there was a vogue for devotional books with embroidered linen or satin covers. The use of fabric as the default option for bindings dates from the early 19th century, when binders began to experiment with cotton cloth, although rough canvas was used for schoolbooks and similar cheap household books from c.1770. Cloth was quickly established during the second quarter of the 19th century as a standard covering material for the prefabricated binding cases which were then transforming bookbinding production. Bookcloth is typically cotton-based, coated or filled with starch or an equivalent synthetic chemical to make it hardwearing, water-resistant, and capable of being blocked with lettering or pictorial designs.

Decoration has long been the aspect of bookbindings and their history that has attracted most interest, both among those who were producing and owning them at the time of their creation and among their successors. The outside of a book is its first and most immediately visible aspect, the part that can be seen even when it is closed and on a shelf: it thus bears the greatest potential to attract or impress users. Down the ages, handsomely decorated bookbindings have been commissioned, collected, valued, sold, and displayed, appreciated not only for their beauty but for the statements they may make about the importance of the book’s contents, or the status of the owner. Much of the published literature on bookbindings is dedicated to these kinds of bindings, but it is important to recognize that all bindings have some kind of decoration, however minimal, and that it is worth studying and understanding the full range of options produced over the centuries.

Bookbinding decoration, like every other kind of art form, has always been subject to ever-shifting tastes and fashions, and each generation had its own ornamental vocabulary within which patterns and styles were created. A 16th-century binding will look different from an 18th-century one because the tool shapes and layout designs belong distinctively to their own time. This applies to plain bindings as well as fancy ones; bookbinders always offered their customers a range of options from the simplest and cheapest to the most luxurious and expensive, with many possibilities in between. Understanding the full picture allows one to recognize bindings of all kinds, to place them within the spectrum of options available, to compare them with other bindings of their time, and to interpret the choices that were made in their creation.

The development of bookbinding design, like all aesthetic fashions, is a process of continual change, dependent partly on the potential of the materials available and partly on the creation and dissemination of new artistic ideas. Styles typically began in one place and spread across continents; English bookbinding was influenced by what was being produced in France and Holland, which in turn was influenced by designs from Italy or other European artistic centres. Across Europe, countries developed variations and characteristics of their own, but at any one time there was a broad commonality of design conventions. In America, where bookbinding began soon after European settlers arrived (the first North American bookbinder is recorded in 1636), styles and techniques followed European, particularly British, models. Bookbinding tools always belonged within the wider ornamental fashions of their time—the neoclassical motifs of 18th-century bindings, for example, are mirrored in contemporary architecture, woodwork, and other decorative arts—but usually with a distinctive twist of their own, making them recognizably intended for binding decoration.

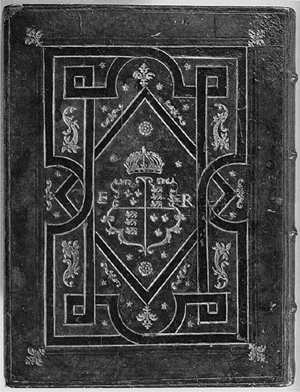

Tanned leather bindings have usually been decorated by building up patterns with heated metal tools, leaving a permanent impression in the surface. Tools may be small individual stamps, large blocks, or wheels with an engraved design around the rim, and are run along a cover to create a continuous line of ornament (fillets and rolls). For greater visual impact, tools can be applied through a thin layer of gold leaf, leaving a gilt rather than a blind impression; this was an Islamic invention, known from at least the 13th century, and many handsome gilt-tooled bindings from Persia and North Africa survive from the 14th and 15th centuries. The technique travelled to Italy and Spain in the 15th century, and gilt-tooled bindings began to be produced in quantity all over Europe from the 16th. The great majority of the countless thousands of tanned leather bindings produced during the hand press period carried some degree of blind- or gilt-tooled decoration, varying from a few lines or simple tools to elaborate designs. At the top end of the market, skilled craftsmen like Jean de Planche, Samuel Mearne, or Roger Payne produced striking and sophisticated bindings; many examples, showing the ways in which styles developed by time and place, will be found in the extensive literature on bookbinding.

Decorative effects on leather bindings could be further enhanced by using inlays or onlays of differently coloured leather, or by applying paint as well as tooling. Leather could also have patterns cut into it (cuir ciselé); this was popular in and around Germany in the late medieval period, but was otherwise uncommon in binding practice. Many of the decorative techniques used on leather were also shared with vellum bindings. Decoration was commonly placed not only on covers and spines, but on board edges, using narrow rolls; leaf edges were usually coloured or sprinkled, or gilded in the case of better-quality bindings. Spine-labelling, using lettered leather labels, became common from the late 17th century; before then, books might have their titles written on their leaf edges or elsewhere, reflecting different storage methods before it became common practice to shelve books upright, spine outwards.

Medieval leather bindings, typically covered with tawed rather than tanned leather, were often largely undecorated, although a vogue for tool-stamped, tanned leather bindings developed in the later 12th century. Special bindings of the Middle Ages tended to rely on other techniques, using covers of ivory, enamel, or jewelled metalwork, made separately and nailed on to the wooden boards. Many medieval abbeys and large churches had treasure bindings like this for bibles and important devotional books, although relatively few have survived.

A 16th-century strapwork binding: brown calf, gold tooling, and black paint. The lower cover of Xenophon’s La Cyropédie (Paris, 1547), bound for Edward VI. © The British Library Board. All Rights Reserved. (C.48.fol.3)

A 19th-century decorated binding: according to contemporary advertisements, L. M. Budgen’s Episodes of Insect Life (London, 1849), published under the pseudonym ‘Acheta Domestica’, was ‘Elegantly bound in fancy cloth’ and sold for 16s. The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford (189 a.42 cover)

The introduction of cloth as the standard covering material for bindings, in the second quarter of the 19th century, saw attention rapidly paid to developing its decorative capabilities. Gold blocking on cloth began in 1832, initially for spine lettering, but quickly adapted to be applied to covers as well. Experimentation during the following decade with abstract and pictorial designs, using gold and coloured inks, led to the production from mid-century of a wide variety of striking publishers’ bindings in decorated cloth. This tradition declined towards the end of the century, as dust jackets evolved; these became increasingly common from the 1880s, initially with printed text but gradually becoming the more pictorial and actively designed covers we are familiar with today. The story of dust jackets and pictorial covers for paperbacks belongs more to design history than bookbinding history, but the importance of these contemporary methods of drawing attention to books by their covers is self-evident.

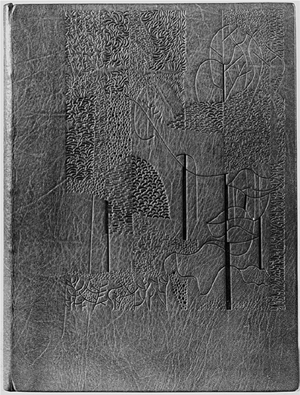

The growth of machine-made cloth binding in the 19th century led to a corresponding decline in the making and decoration of leather bindings, although the trade never died out. A reaction against a feeling that artistic standards in bookbinding had fallen was initiated in the 1880s by T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, whose beautifully crafted bindings, produced to his own designs, inspired a revival of interest in handcrafted bookbinding. A tradition of fine bookbinding flourished in many countries during the 20th century; in England, the formation of the Guild of Contemporary Bookbinders in 1955 (subsequently renamed Designer Bookbinders) provided a focus for this movement, within which numerous contemporary binders have continued to produce bindings combining the highest quality of craftsmanship with artistic flair, and experimentation with the possibilities of bookbinding as an art form.

Nineteenth- and 20th-century bookbindings commonly have decoration on their covers or dust jackets that reflects the content of the book. This is a modern development; throughout the medieval and hand press periods, bookbinding decoration was normally abstract, with no attempt to use designs to represent content. There are exceptions, but they are very few in proportion to the bulk of what was produced.

A 20th-century binding by Edgar Mansfield, an influential figure in the development of the Designer Bookbinder movement in the later 20th century: blind-tooling on yellow goatskin. The upper cover of H. E. Bates’s Through the Woods (London, 1936). © The British Library Board. All Rights Reserved. (C.128.f.10)

Bookbinding was generally carried out as a professional activity within the broader umbrella of the book trade. During medieval times, some bookbinding was undertaken within monasteries as a logical adjunct to the writing and copying of MSS, but as soon as a secular trade in making and selling books developed (around the 12th century), binders emerged as one subset alongside parchment makers, scribes, and stationers.

The organization of binding work varied a little from country to country according to local custom, but throughout the early modern period binders generally entered the trade through apprenticeship to an established practitioner, followed by formal membership of a guild or similar trade association. In England, there was never a separate bookbinders’ guild, and London binders (where much of the trade was concentrated) belonged to the Stationers’ Company, which also embraced printers and booksellers. Binders were typically the poor relations within this framework, in terms of both earnings and social status, and many binders who succeeded financially did so by diversifying their activities into selling books, stationery, or other wares. The relationship between booksellers and binders in the early modern period—the extent to which binders had independent business relationships, or were employed by the booksellers—is not well documented. It is increasingly recognized that books were often bound before being put on sale, but there is little evidence to suggest that edition binding in any deliberate sense was carried out much before the 19th century. Selling books ready-bound seems to have been more common in Britain than in continental Europe, where the tradition of issuing books in paper wrappers, to be bound to a customer’s specification, continued well into the 20th century.

Before the 19th century, binderies were typically small establishments run by a master with a handful of assistants (who might be apprentices, journeymen, or members of his family; women were often involved in some of the operations, such as folding and sewing). In France, there was a recognized distinction between forwarders (relieurs) and finishers (doreurs); in Britain, Germany, and elsewhere these roles were less formally identified, although individuals within workshops are likely to have specialized. Representations of European binding workshops between the 16th and 18th centuries, of which a number survive, commonly show something between two and eight people at work in one or two rooms carrying out the various activities of sewing, beating, covering, and decorating involved in binding production.

All this changed during the 19th century, when the trade was gradually transformed by mechanization. Growing book production, the development of cloth casing, and the invention of machines to carry out binding processes led to binderies becoming much bigger operations with factory-like assembly lines. During the first half of the century, many of the operations such as folding, sewing, and attaching cases were still carried out by hand, but the second half saw the introduction of steam-powered folding machines (from 1856), sewing machines (from 1856), rounding and backing machines (from 1876), case-making machines (from 1891), gathering machines (from 1900), and casing-in machines (from 1903). Many of these were first introduced in America. Bookbinding today, for the great majority of the books issued through normal publishing trade channels, is carried out as an automated industrial process, whose capacity has been enhanced since the 1950s by the development of new fast-drying inks and glues.

An 18th-century binder’s workshop: a relatively small number of people carry out the various operations involved in forwarding and finishing; from C. E. Prediger, Der Buchbinder und Futteralmacher, vol. 2 (1745). Private collection.

Bookbindings play an important functional role in the life of every book, but their impact and potential to affect the values associated with books goes beyond this. The statement that a luxuriously bound book can make about the importance of its contents, or its owner, is a tradition that stretches back through generations of wealthy bibliophiles to the treasure bindings displayed on medieval altars. Queen Elizabeth I liked her books bound in velvet; her royal library presented a rich and colourful display to impress visitors, and drew together a collection of books that she found individually satisfying to look at and to handle. Less wealthy owners have also taken active delight in the aesthetic satisfaction which bindings can bring. Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary (15 May 1660) that he purchased books ‘for the love of the binding’, and had many of his books rebound to create a uniform image. Finely bound books have often been created as gifts, sometimes in the hope of influencing potential patrons. The admiration and expense of fine bindings have also generated criticism; Gabriel Naudé lamented ‘the superfluous expenses, which many prodigally and to no purpose bestow upon the binding of their books … it becoming the ignorant only to esteem a book for its cover’ (Naudé, 61). Many early purchasers were at least as concerned about functionality as decoration—they wanted their books sound and well made, without missing leaves—and wealthy owners did not necessarily have fancy bindings.

Early bookbinding practice is not well documented; contemporary manuals or archival sources on binders and their lives are relatively scarce before the 19th century. The bindings themselves constitute the largest body of evidence for exploring bookbinding history. The serious study of the subject began in the late 19th century, initially with a focus on the artistic qualities of fine bindings, maturing into a tradition of comparative study of surviving bindings to identify sets of tools used together, from which workshops and their dates of operation may be deduced. Bindings can therefore be attributed to particular binders, times, and places. Towards the end of the 20th century increasing attention was paid to structural aspects as well as decorative ones, with a growing emphasis on the full range of bindings produced, the plain and the everyday as well as the upmarket and the fine. The idea of systematically collecting bindings for their own sake is similarly a relatively recent development, and a number of important collections of fine bindings were formed in the 20th century.

Bookbinding studies have in the past been regarded as having a rather peripheral role in the overall canon of historical bibliography, compared with printing and publishing history, or work more directly focused on textual or enumerative bibliography. Bookbindings have been thought to be incidental to and unconnected with the works they cover, and the past emphasis on fine bindings has lent the subject an art-historical flavour that can veer towards dilettantism. More recent developments in book history, concerned with the ways that books were circulated, owned, and read, have created a framework in which it is easier to see bindings as an integral part of that whole. It is now widely recognized that the reception of works is influenced by the physical form in which they are experienced—an area where bindings play an important role. A reader’s expectations may be conditioned by the permanence, quality, or other features of a book’s exterior. Bindings may reveal ways in which books were used—how they were shelved or stored, how much wear and tear they have received—and the rebinding of books by later generations of owners may reflect changing values (contemporary bindings of Shakespeare are typically much simpler than the elaborate gilded goatskin in which 19th-century owners rebound early editions of his works). Cheap and temporary bindings, or bindings whose internal structure shows corner-cutting techniques, may indicate likely original audiences.

More obviously, knowledge of binding history allows us to recognize when and where bindings were made, and therefore where they first circulated. In the early modern period, books were not necessarily bound and first sold where they were printed, as printed sheets often travelled significant distances before being bound. Imprints should not be taken as an indicator of place or date of binding, for which decorative, structural, and other material evidence, interpreted by comparison with other bindings, is a surer guide. Bindings may also incorporate direct evidence of early ownership, in the form of names, initials, or armorial stamps on the covers or spine, practices that have been common in Europe since the 16th century.

D. Ball, Victorian Publishers’ Bindings (1985)

C. Chinnery, ‘Bookbinding [in China]’, www.idp.bl.uk/education/bookbinding/bookbinding.a4d, consulted Mar. 2006

M. M. Foot, The History of Bookbinding as a Mirror of Society (1998)

E. P. Goldschmidt, Gothic and Renaissance Bookbindings (1928)

D. Haldane, Islamic Bookbindings (1983)

H. Lehmann-Haupt, ed., Bookbinding in America (1941)

R. H. Lewis, Fine Bookbinding in the Twentieth Century (1984)

Middleton

G. Naudé, Instructions Concerning Erecting a Library (1661)

H. M. Nixon, English Restoration Bookbindings (1974)

Nixon and Foot

J. B. Oldham, English Blind-Stamped Bindings (1952)

D. Pearson, English Bookbinding Styles 1450–1800 (2005)

N. Pickwoad, ‘Onward and Downward: How Binders Coped with the Printing Press before 1800’, in A Millennium of the Book, ed. R. Myers et al. (1994)

E. Potter, ‘The London Bookbinding Trade: From Craft to Industry’, Library, 6/15 (1993), 259–80

J. Szirmai, The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding (1999)

M. Tidcombe, Women Bookbinders 1880–1920 (1996)