The History of the Book in France

VINCENT GIROUD

The history of the book in France reflects the peculiar dynamics between culture and power that have characterized the country throughout its history. These dynamics take two principal forms. The first is a constant trend towards centralization, resulting in the supremacy of Paris, always but never successfully challenged. The second is a long tradition, beyond regime changes, of state intervention or control in cultural matters. Yet this situation also carries contradictions and paradoxes, including the perpetual gap between cultural policies, stated or implemented, and a reality that, through inertia or active resistance, counters them.

Books, in France as everywhere else, preceded printing. By the 2nd century AD in Gaul, dealers in codices were established in the major Roman cities of the Rhône valley (Vienne, Lyons), indicating that Latin literature was distributed in the country. In the 4th century, as Christianity spread, intellectual centres focusing on the dissemination of sacred texts were formed around the great figures of the period, such as Martin in Tours and Marmoutiers, and Honorat on and off the Mediterranean coast. Three centuries later, under the Merovingian kings, came the first wave of monastic foundations, some in the main cities (Paris, Arras, Limoges, Poitiers, Soissons) but many in isolated areas, mostly in the northern half of what is now France. The majority were founded between 630 and 660: Luxeuil, near Besançon; Saint-Amand, near Valenciennes; Jouarre, near Meaux; Saint-Bertin, near Saint-Omer; Saint-Riquier, in Picardy; Fleury (now Saint-Benoît), on the Loire near Orléans; Jumièges, on the Seine south of Rouen; Chelles, to the northeast of Paris; Corbie, near Amiens. These, along with cathedral schools in the cities named above, as well as Arles, Auxerre, Bordeaux, Laon, Lyons, Toulouse, and others, became and remained the principal centres of book production in the country until the creation of universities in the 13th century. Their scriptoria were among the most important of medieval Europe. While many of these made books for the monastery’s use, some became book production centres, specializing—like modern publishing houses—in certain types of MS. Commentaries on the Fathers of the Church came from Corbie, didactic texts from Auxerre and Fleury-sur-Loire. Saint-Amand was famous for its gospels and sacramentaries. Saint-Martin in Tours became a leading producer of large, complete bibles, of which the Bible of King Charles the Bald (823–77), now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), is an outstanding example. On becoming abbot of the recently founded Cluny in 927, Odon brought with him 100 MSS; their number grew to 570 by the end of the 12th century. The second wave of monastic foundations—in the 11th century, especially under the impulse of St Bernard—resulted in an increase in MS production and in new networks for their dissemination, with the Grande Chartreuse (1084), Cîteaux (1098), and Clairvaux (1115) forming important libraries.

The university of Paris, created in 1215, while opening up the territory of learning beyond the confines of monasteries and cathedral schools, produced an immediate demand for books—as did the foundation by Cardinal Robert de Sorbon, in 1257, of a college for poor theology teachers that was to bear his name. By the late 13th century the Sorbonne, enriched by donations, had (for the time) a large library. In 1338 it contained 1,722 volumes, 300 of them publicly accessible (though chained against theft) in the main reference room (grande librairie), the remainder locked up in the petite librairie, from which they could be made available for consultation and circulation. In addition to academic libraries, a book trade appeared, with stationers operating workshops in the Latin Quarter to furnish students and teachers with copies of MSS. Laymen, responsible to the university’s religious authorities, ran the pecia system: for a fee, students or professional copyists could borrow MSS established from a model copy (the exemplar) previously checked by university commissions. The dealers (libraires-jurés), affiliated to the university, were to check the new copies for completeness and accuracy. Like the monasteries before them, universities acquired specialisms—Paris in theology and Orléans in civil law—differences that were reflected in the libraries and book trades flourishing around those two centres. With the development of biblical exegesis in the 12th century, new types of bible, incorporating commentaries (some running to fourteen volumes), became a Parisian specialty in the 13th century, as did one-volume ‘pocket bibles’. Another speciality, recorded by Dante in the Divina Commedia (Purgatorio, 11.80–81), was illumination, with workshops such as that of the Limbourg Brothers producing luxury volumes of which the spectacular books of hours of the period remain celebrated examples.

Although lay books par excellence, books of hours and psalters were both in Latin; a genuine vernacular literature appeared in the 12th century, both in the langue d’oc spoken in southern France and the langue d’oïl spoken in the north. At first the transmission of these texts was oral. Thus, there are no early MSS of the 9th-century Chanson de Roland, which began to be written down in the early 11th century. Of the five verse novels of Chrétien de Troyes (fl. 1170–85), the most important writer of his age, there are no MSS before 1200. As early as the 13th century, the most widely disseminated French work was the allegorical, didactic Roman de la Rose (first part c.1230, second part c.1270): about 250 complete copies are preserved. Troubadour poems started being collected only during the 14th century. By then, Christine de Pisan, the first real woman of letters, operated the equivalent of a small private scriptorium to disseminate her poems.

Considering that only about 10 per cent of the French population was literate in 1400, books were used and enjoyed by a privileged minority. An even smaller minority within that minority, the first French book collectors, appeared at that time. The famous image of King Charles V among his books, like a monk (BnF, Fr. MS 24287), was a political statement of sorts. The king’s library, to be sure, was as much an ancestor of the BnF as a private library. It also served as a model for the aristocracy, a model not only followed but surpassed by some members of the royal family, who were truly the first French bibliophiles—especially Jean, duc de Berry (the king’s brother) and their cousin Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy: both owned some of the most expensive books of their time. The 15th century also marks the beginnings of urban patronage, characteristic of the rise of an identifiable bourgeoisie, with well-known instances in Bourges and Rouen.

Humanism, as has often been pointed out, came to France as a result of the sojourn of the popes in Avignon (1309–78), which brought Petrarch (Petrarca) and Boccaccio to the country, while Poggio Bracciolini toured abbeys (Cluny) and cathedral schools (Langres) in search of MSS of classical authors. Avignon became one of the earliest centres of paper production in France (Champagne was another) as the new material began to replace parchment. It also figures in the immediate prehistory of the invention of printing, as a certain Procopius Waldfoghel formed an association with local scholars and printers in 1444 to develop a system of ‘artificial writing’ about which nothing else is known. Other prototypographical experiments may have taken place in Toulouse around that time (see 6, 11).

Printed books were introduced into France before printing was established in the country. Johann Gutenberg’s associates Johann Fust (who died in Paris in 1466) and Peter Schoeffer brought their productions to the French capital, where they were also available through their representative, Hermann de Staboen. Once Johann Heynlin and Guillaume Fichet had established the first French printing press in a Latin Quarter house owned by the Sorbonne, the new technology spread fairly quickly to the provinces. Guillaume Le Roy printed the first book in Lyons in 1473. Presses are recorded at Albi in 1475; at Angers and Toulouse in 1476; at Vienne and Chablis (the northern Burgundy wine village) in 1478; in Poitiers in 1479; at Chambéry and Chartres in 1482; at Rennes and two other Breton cities in 1484 (the first work in the Breton language was printed as early as 1475); at Rouen in 1485; at Abbeville in 1486; at Orléans and Grenoble in 1490; at Angoulême and Narbonne in 1491. Save for a few ephemeral undertakings, like the one Jehan de Rohan ran in his Breton château of Bréhant-Loudéac in 1484–5, most were permanent establishments. Leaving aside the Alsatian region, which was politically and culturally part of the Germanic world, there were presses in about 30 French cities by 1500.

Lyons was not a university town but a major commercial centre with frequent contacts with northern Italy and Germany. It soon became the second most active city for printing in France and, in the 1490s, the third in Europe. Books were sold at its four annual fairs. Of its emergent prosperous, progressive merchant class, Barthélémy Buyer, Le Roy’s patron, was an outstanding example. Paper mills operated in Beaujolais nearby and in not-too-distant Auvergne. By 1485 Lyons boasted at least twelve printers, most of them coming from Germany, such as Martin Huss from Wurtemberg, whose Mirouer de la rédemption de l’humain lignaige (1478) is the first illustrated book printed in France (using woodcuts from Basel). To the same Huss is owed the first known representation of a printing office, in the 1499 Grande danse macabre, a powerful image showing the emissaries of death grabbing the compositor, pressmen, and corrector caught in the middle of their respective tasks. Also in Lyons, Michel Topié and Jacques Heremberck printed Bernhard von Breydenbach’s Sainctes peregrinations de Jerusalem (Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam), the first French book illustrated with engravings (the plates copied from the woodcuts of the 1486 Mainz edition). Half the titles printed in French before 1500 originated from Lyons, including the very first, the Légende dorée which Le Roy issued in 1476.

Although Lyons to a great extent showed the way, Paris was already the capital of the book in France and, after Venice, the second most active publishing centre in Europe in the 15th century. Printers and booksellers soon congregated in the southeastern part of the Latin Quarter, especially along the rue Saint-Jacques (where Ulrich Gering and his associates set up shop after Heynlin left the Sorbonne). Paper and parchment dealers were situated further east, in the Faubourg Saint-Marcel. The book trade established itself mostly along the river and on the Île de la Cité. Most of the early Parisian printers came from abroad, especially the German-speaking world. The first ‘native’ printing office, the Soufflet Vert, was opened in 1475 by Louis Symonel from Bourges, Richard Blandin from Évreux, and the Parisian Russangis; Pasquier Bonhomme, who printed the first French book issued in the capital, probably set up his press in that same year. The university’s presence influenced the types of book first printed in the city: pedagogical works like Gasparino Barzizza’s letters and spelling manual, Fichet’s Rhétorique, classical authors in particular favour in schools (Cicero, Sallust), or works popular in the legal and clerical professions, like Montrocher’s Manipulus Curatorum. The city’s long association with illuminated MSS was also a factor: a large part of the Parisian 15th-century output (700 of the 4,600 incunables that originated in France) was printed books of hours, produced at times with blank spaces left so that they could be decorated by hand. These were the specialty of Jean Du Pré and Pierre Pigouchet and, after them, Antoine Vérard, who before becoming a prolific and successful printer ran a workshop of copyists and enlumineurs. The continued prestige enjoyed by MSS also explains some of the typographical characteristics of many French incunables: the preference for the so-called gothic bastarda type, closest to late medieval calligraphy (whereas Gering and his colleagues had initially used an elegant roman type cast from Italian models); and the taste for elaborately decorated initials also reminiscent of illumination (which recur in French books well into the 17th century).

Other printing cities in France were often university towns, like Angers and Tours. In most cases, however, the Church was the promoter, the resulting products being books needed for religious services: breviaries were printed at Troyes and at Limoges, and copies of a missal and psalter at Cluny. The patronage of the Savoy court played an important role in Chambéry, where Antonine Neyret issued his Livre du roy Modus, the first French hunting book, in 1486.

Much 15th-century book production was targeted at the academic world or the Church, while books of hours and chivalric romances were favoured by the rich bourgeoisie. Literature as it might be understood now—including many reprints of the Roman de la Rose and rare editions of the greatest poet of the previous generation, François Villon (fl. 1450–63)—represented a small percentage of the trade’s output. Yet more popular forms of printing appeared and spread in the shape of small pamphlets printed in French in gothic type, ranging from current news to practical handbooks; many have not survived.

Naturally, the political powers viewed the invention of printing with movable type with interest and encouraged it. There are signs that Heynlin was protected by Louis XI (r. 1461–83); the Italian campaigns of his son Charles VIII in 1495–8 (their spoils leading to the establishment of royal MS collections in Amboise) spurred the spread of humanism in France.

Paris, with 25,000 titles, and Lyons, with 15,000, continued to dominate French printing in the 16th century, while Rouen established itself as the country’s third printing centre (with Toulouse fourth). The proportion of titles printed in French grew rapidly, the balance relative to Latin tilting towards the vernacular in the 1560s. At the same time, humanism brought to France an unprecedented interest in Greek texts: Gilles de Gourmont printed the first French book in Greek in 1507, while François I gathered at Fontainebleau the best collection of Greek MSS in western Europe, appointing as its curator Guillaume Budé.

Between 1521, when the Paris faculty of theology condemned Luther and obtained from the Paris parliament the right of control over all religious publications, and 1572, the year of the St Bartholomew Massacre, printing was intimately connected with the spread of the Reformation in France, with the king acting at first as an arbiter. His sister, Marguerite de Navarre, protected the reformist circle formed around Guillaume Briçonnet, bishop of Meaux. The king himself defended the biblical scholar Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, whose translation of the New Testament was issued by Simon de Colines in 1523, two years after the faculty of theology had banned biblical translations. But he was powerless to prevent the execution of Louis de Berquin, the translator of Desiderius Erasmus, in 1529, and turned to repression when Lyons-printed broadsides attacking the Catholic mass were posted in 1534, an indirect cause of the condemnation and execution of Antoine Augereau in the same year. For a while, early in 1535, printing was banned altogether. Then came a series of regulations destined to establish royal control over all printing-related matters: the institution of copyright deposit (the Edict of Montpellier, 1537), the regulation of the printing professions and the creation of the post of Imprimeur du Roi (1539–41), and the tightening of censorship in 1542. More such measures were adopted by Henri II. The Ordinance of Moulins (1566) made general the obligation to obtain a privilege, to be granted exclusively by the Chancery. The success of these repressive measures is attested by Étienne Dolet’s execution (1546) and the departure of Robert Estienne for Geneva following the deaths of François I (1547) and Marguerite (1549).

The first half of the 16th century, heralded by the publication of Erasmus’s Adagia at Paris in 1500, is dominated by the great humanist printers: in Paris Jodocus Badius Ascensius, Geofroy Tory, Colines, Guillaume Morel, Michel de Vascosan, and above all the Estiennes; in Lyons Sebastianus Gryphius, Dolet, and Jean de Tournes. The dissemination of humanism was also facilitated by entrepreneurs like Jean Petit, the most prominent French publisher of the age, who issued over 1,000 volumes between 1493 and 1530. While the ‘archaic’, gothic appearance of the previous period was still widespread, humanist printers favoured roman types such as the one Estienne used for Lefèvre’s revisionist Quincuplex Psalterium (1509)—thus typographic innovation, soon to be codified by Tory in Champfleury (1529), typically accompanied progressive thinking. It led to the work of the great French typographers Claude Garamont, Robert Granjon, and the Le Bé dynasty in Troyes, suppliers of Christopher Plantin’s Hebrew types. One of the most admired typographical achievements of the period is Le Songe de Poliphile, a French version of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili; printed by Jacques Kerver in 1546, it also marked the apogee of the French Renaissance illustrated book with its beautiful woodcuts, attributed to Jean Goujon and Jean Cousin.

Lyons, having neither a university nor a parliament, enjoyed greater political freedom, at least until the early 1570s, to the point of becoming a Calvinist city in 1562–72. At least fifteen editions of the Bible in (banned) French translation appeared there between 1551 and 1565. In 1562 de Tournes published at Lyons the first edition of Marot’s translation of the Psalms completed by Beza, ‘the most ambitious publishing project of the 16th century’ (Chartier and Martin, 1. 321) for which nineteen Parisian printers were contracted (two, Oudin Petit and Charles Périer, were victims of the St Bartholomew Massacre), as well as many in the provinces. After 1572, Geneva (where de Tournes’s son and successor moved in 1585) replaced Lyons as the principal centre of dissident religious texts printed in French (see 27).

This ideological effervescence was accompanied by an extraordinary literary flowering: Rabelais (Pantagruel and Gargantua, first printed at Lyons in 1532 and 1534), the Lyonnais Maurice Scève (Délie, 1544), du Bellay (Défense et illustration de la langue française, 1549 and many later editions), Ronsard (Les Amours, two editions in 1552), the other poets of the Pléiade group, and Montaigne, whose Essais were first printed at Bordeaux. André Thevet popularized voyages of discovery with his Singularitez de la France antarctique (1557). Ambroise Paré fostered the renovation of surgery with his Cinq livres de chirurgie (1572)—its Huguenot printer, Andreas Wechel, left Paris for Geneva that same year—and Androuet du Cerceau’s Plus excellents bastiments de France (1566–79) promoted the canons of the Fontainebleau School.

Montaigne’s library (described in Essais, 2. 10) is that of a cultivated reader of wide intellectual curiosity; it differs from that of a bibliophile like Jean Grolier, earlier in the century, with his particular interest in bindings. The 16th century can rightly be called the golden age of French binding, with names like Étienne Roffet (named Royal Binder in 1533), Jean Picard, Claude Picques, Gomar Estienne (no relation of the printing dynasty), and Nicolas and Clovis Eve (the latter active during the 1630s). Progress was also made in printing music, first by Pierre Haultin, then by Pierre Attaingnant of Douai (fl. 1525–51), who became the first royal printer of music, to be succeeded by Robert Ballard, whose family retained the office for more than two centuries.

The Wars of Religion, for all their human cost, resulted in relatively little destruction of books (the main casualties were in the libraries of Cluny, Fleury, and Saint-Denis). They generated, on both sides, a mass of propaganda and counter-propaganda (362 pamphlets printed at Paris in 1589 alone). On the Catholic side, they resulted in a revival of liturgical and patristic literature at the end of the century, often involving—in Paris and in Lyons—groups of printers operating as ‘companies’ to share the publication of particular works. Another, long-term consequence of the Counter-Reformation, the establishment of Jesuit schools throughout the country, produced a rise in literacy and fostered the development of new printing centres in medium-sized cities such as Douai, Pont-à-Mousson, and Dole.

Historians of the book who regard the 16th century, especially the reign of Henri II (1547–59), as the apogee in French book arts from both a technical and an aesthetic standpoint, view the 17th century as a period of decline. This applies to the number of titles printed (not, however, to the total output), with Parisian production dropping to 17,500 titles (excluding pamphlets). Lyons, meanwhile, kept its provincial supremacy in absolute terms, but declined in proportion, challenged by other cities, especially Rouen. The development of the paper industry, discouraged by heavy taxes, was further slowed down by the growing shortage of rags, which led to a serious crisis until the 1720s. The quasi-medieval organization of the book trade stifled initiative. Despite Denys Moreau’s attempts under Louis XIII, and with the exception of Philippe Grandjean’s efforts at the end of the century, the triumph and ubiquity of Garamond type did not stimulate typographical innovation. Nor is the period particularly notable for its illustrated books, though significant exceptions include Jean Chapelain’s Pucelle with engravings by Abraham Bosse after Claude Vignon (1656) and, in the later period, Israel Silvestre’s and Sébastien Leclerc’s festival books documenting Versailles’s grandest occasions.

The 17th century is notable for other reasons. First, books and reading habits—the result of a higher literacy rate, which by 1700 averaged 50 per cent—became more general. This applied to men more than to women, to cities more than to the countryside, and to the areas north of a line going from Saint-Malo to Geneva (known as the ‘Maggiolo line’ after the author of a survey in the late 1870s) more than to western, southwestern, and southern France. Beyond the prestigious collections formed by Jacques-Auguste de Thou, Cardinal Mazarin, Louis-Henri de Loménie, comte de Brienne, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, and the Lamoignons, private libraries, even of modest size, became normal among the growing merchant and legal professions in Paris and most French towns. In the lower echelons of society, the spread and lasting success of the Bibliothèque bleue, which made Troyes the fourth most important printing city in 17th-century France, is a signal phenomenon, highlighting the growing role of non-conventional channels (such as itinerant pedlars) in book distribution.

The second notable factor is the bolstering of political controls over all matters relating to the printing and selling of books after the period of unrest following the relatively liberal reign of Henri IV (1589–1610). Richelieu (prime minister 1624–42) and his successors, suspicious of provincial printing, allied themselves with the Parisian printing oligarchy (Sébastien Cramoisy and Antoine Vitré, among others), rewarding them with privileges (and privilege extensions) for lucrative publications in exchange for their docility: Vitré was thus among the publishers who denounced the poet Théophile de Viau for freethinking in 1623. Censorship was taken away from the universities and concentrated in the hands of the chancellor, a policy reinforced when Pierre Séguier was appointed to the chancery in 1633. The Imprimerie royale, installed in 1640 at the Louvre, with Cramoisy as its first head, both conferred prestige and exercised control. Even the Académie française (1635) was intended partly as a group of royal censors. Similar strictures on the rise of newsletters were maintained by granting an exclusive privilege to Théophraste Renaudot’s Gazette de France (1631).

As controls grew, however, so did the inability of the authorities to enforce them, as shown by the massive pamphlet literature, printed and disseminated throughout France, that accompanied the revolt known as the Fronde (1649–52)—more than 1,000 titles are recorded in its first and final years, many of them personal attacks on Mazarin, the prime minister, so that the term mazarinade was coined to describe them (he himself collected them). Among many glaring indications of the failures of the privilege system is the example of Sully (prime minister under Henri IV), who did not bother to apply for one when publishing his memoirs in 1638. A longer-term phenomenon with far-reaching implications in the publishing world was the Jansenist crisis, which began in 1643 when Arnauld and his Port-Royal allies protested against the papal condemnation of Jansen’s Augustinus, attacking the Jesuits in return. Not only did the ensuing conflict lead to a vast number of publications, largely unauthorized, on both sides, it also destabilized the Parisian printing establishment. The paradoxes of this period are typified by the fact that Pascal’s publisher, Guillaume Desprez, went to the Bastille for printing the immensely successful Provinciales (1656–7)—he was also to publish the posthumous Pensées (1669)—but became rich in the process.

The policies of Louis XIV—genuine ‘cultural policies’ ahead of their time—also reveal both great determination to control print and ultimate powerlessness to do so. His measures included the creation of more academies (1663–71), the incorporation of writers (Boileau, Racine, La Fontaine) into an all-encompassing system of court patronage, the reduction and eventual limiting of the number of authorized printers, and imposing a cap on the number of provincial printing offices. In 1667, powers to enforce book controls and exercise censorship were given to the Lieutenant of Police. In 1678–9, local privileges were suppressed: some parliaments, like Rouen, had taken advantage of their relative autonomy to encourage local business. While these policies, though repressive enough, were unsuccessful in stemming the spread of ‘bad’ books, their chief victim was provincial printing. By the most conservative estimates, at the end of Louis XIV’s reign Paris produced 80 per cent of the national output. Another unintended consequence of French absolutism was the prosperity of foreign printers of French books, who now contributed 20 per cent of the total, a proportion that peaked at 35 per cent in the middle of the 18th century.

The first decades of the 17th century had seen the triumph of the religious revival launched by the Counter-Reformation, St Francis de Sales’s Introduction à la vie dévote, first printed at Lyons in 1609, being its most famous title. It is contemporary with another publishing phenomenon, the success of Honoré d’Urfé’s 5,000-page novel L’Astrée (1607–24), the ‘first bestseller of modern French literature’ (Chartier and Martin, 1. 389). The baroque and classical periods are characterized above all by the enormous development of the theatre, as shown by the careers of Corneille, despite the Académie’s strictures on Le Cid (1637); Molière, despite his brush with censorship; and Racine. Typically, printer-publishers (like Augustin Courbé and Claude Barbin) formed groups to issue plays and divided the imprint between themselves. Meanwhile, clandestine reprints appeared almost immediately, originating in the provinces (such as Corneille’s native Rouen) or abroad (especially from the Elzeviers). The success of these piracies also revealed the vast appetite of the market. Barbin, the leading literary publisher of the day, was also responsible for La Fontaine’s Fables (first edition, 1668) and Mme de La Fayette’s novel La Princesse de Clèves (1678), published anonymously. In 1699 his widow issued Fénelon’s Télémaque, which was pirated twenty times that year and went through innumerable editions. Among the century’s other notable productions are the first French world atlas, Nicolas Sanson’s Cartes générales de toutes les parties du monde (1658); the Port-Royal Grammaire (1660–64) and Logique (1662); and the founding text of French art history, André Félibien’s Entretiens sur les plus excellens peintres anciens et modernes (1666–88).

The early 18th century is dominated by the figure of the Abbé Bignon (1662–1747), appointed in 1699 by Chancellor Pontchartrain, his uncle, to be in charge of all book policies (the title Directeur de la librairie became official only in 1737). Bignon was, in fact, a sort of ‘minister of literature’ (to use Malesherbes’s phrase, though he claimed there was no such thing). He organized a countrywide publishing survey in 1700 and spearheaded the development of provincial academies, while proving an inspired leader of the Bibliothèque royale from 1719 until 1741. Although the number of censors increased (there were close to 200 by 1789), and despite a few well-known cases such as the banning of Voltaire’s Lettres philosophiques in 1734 (they had first come out in English the previous year), Bignon’s influence and that of his successors was largely a moderating one. In fact—and this is one of the many paradoxes of the late ancien régime—the agents of the repressive policies were chiefly animated by pragmatism. To counter the growing number of illicit imports of French books printed in Germany or Holland, Bignon created a system of ‘tacit’ or oral permissions to legitimize provincial piracies. Chrétien Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, director of the Librairie in 1750–63, was a friend of the philosophes and pursued this trend, protecting Jean-Jacques Rousseau and tipping off the printers of the Encyclopédie against possible arrest. But he was caught in another French 18th-century paradox: although the monarchy was largely sympathetic to the Enlightenment, it had to contend with other traditional sources of censorship, the Church and parliaments, whose interventions (generally after publication) eventually turned into embarrassments for the Crown, as in the case of Helvetius’ De l’esprit (1758–9).

In 1764, only 60 per cent of the books printed in France were ‘legal’. Of the ‘illegal’ works, most were banned religious books (Protestant, Jansenist, or otherwise unorthodox). The rest were unauthorized provincial reprints, political satires, or pornographic literature (which boomed in the 18th century, the marquis de Sade being one example of this trend among many). A large number of the century’s ‘great books’— Candide may be the most famous—were for one reason or another illegal. The absurdity of this situation, denounced by Diderot in his Lettre sur le commerce de la librairie (1763), was partly remedied in 1777 when Miromesnil, Keeper of the Seal, modified the privilege system to legitimize a large portion of provincial, clandestine productions, while recognizing for the first time that literary property belonged to the author. Ultimately, to paraphrase Tocqueville (Malesherbes’s great-grandson) in L’Ancien Régime et la révolution, the real winners were men of letters, propelled to the rank of major political figures of international stature.

Against this backdrop, the French 18th century rivals the 16th for its accomplishments in the arts of the book. Their prestige was such that Louis XV, as a child, was initiated into printing, while the regent and the marquise de Pompadour published their efforts as amateur book illustrators. Some of the great painters of the age—Oudry, Boucher, Fragonard—contributed to the genre, along with the more specialized book illustrators Charles-Nicolas Cochin, Charles Eisen (his most celebrated work was the 1762 ‘Fermiers Généraux’ edition of La Fontaine’s Contes), Hubert-François Gravelot, and Jean Michel Moreau le Jeune. Louis-René Luce and the Fournier family renewed typography early in the period, while the Didots brilliantly interpreted neo-classical taste during the latter half. Technical innovation came to the paper industry as well: the Annonay mills near Saint-Étienne made the names of Canson, Johannot, and Montgolfier famous, while to the south of Paris the Essonnes mill, purchased by a Didot, became the country’s most technologically advanced by the last years of the ancien régime. Equally esteemed for their technical mastery and decorative brilliance, the Deromes, Padeloups, and Dubuissons produced bindings of unsurpassed elegance. The enlightened aristocracy and princes of the Church—François-Michel Le Tellier, Joseph Dominique d’Inguimbert, the duc de La Vallière, the prince de Soubise, the marquis de Méjanes, the marquis de Paulmy—formed bibliophilic collections, some of which are now the great treasures of Parisian or provincial libraries. There was an expanded market for ambitious editorial projects: the Encyclopédie, naturally, the Oudry-Jombert Fables of La Fontaine, and Buffon’s Histoire naturelle, printed by the Imprimerie royale (1749–89). Printed across the river from Strasbourg, the Kehl edition of Voltaire’s works (1785–9), launched by Charles-Joseph Panckoucke before the writer’s death in 1778, was brought to completion by Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais amidst many difficulties, and sold out despite two concurrent piracies. Panckoucke typifies the growing contemporary awareness of the publisher’s role, distinct from the printer’s. The book trade also acquired greater professional autonomy. These advances were paralleled by the growth and success of book auctions. There were between 350 and 400 book dealers in Paris in 1789, most of them established in the traditional area around Notre-Dame and along the river, but many migrating to the Palais-Royal area. Some doubled as cabinets de lecture (small lending libraries), institutions that remained in favour throughout the first half of the following century. Meanwhile, the first genuine public libraries appeared: in 1784 there were eighteen in Paris, beginning with the Bibliothèque royale, open twice a week to ‘everyone’, and sixteen in the provinces; some had begun as private collections, others as religious or institutional collections, others prefigured municipal libraries.

One of the first initiatives of the Revolution was to abolish royal censorship and to proclaim the freedom of writing and printing, both included in the Declaration of the Rights of Man of 26 August 1789. The office of the Librairie and even copyright deposit, seen as a repressive measure, were terminated, along with printers’ and all other guilds. The copyright legislation adopted by the Convention in 1793 (a maximum protection of ten years after the author’s death) advanced many titles into the public domain. The nationalization of church properties (decreed in November 1789), the confiscation of works belonging to émigrés and (after 1792) the royal collections, followed by the libraries of all suspects under the Terror of 1793–4 (coinciding with a de facto re-establishment of censorship), displaced vast numbers of books and MSS. To a considerable extent, this benefited the Bibliothèque nationale (BN) and future municipal libraries. The revolutionary book world, especially in Paris, has been aptly compared to a ‘supernova’ (Hesse, 30), growing to nearly 600 libraires and printers, most of them small, precarious units, while 21 traditional houses, having lost their clientele, went bankrupt in four years. The explosion of periodicals and ephemera was accompanied by a decline in book production, and piracy was rife. Among the many worthy projects launched during that short period, the last king’s librarian, Lefèvre d’Ormesson, started a ‘Bibliographie universelle de la France’ in 1790. He was guillotined in 1794. The same fate was met that year by Malesherbes and by Étienne Anisson-Duperron, head of the Imprimerie royale, where he had been a strong promoter of technical innovation.

The Napoleonic system, so much of which has survived in modern France, restored stability through an approach that was, in fact, the opposite of the free-market model favoured in the first stages of the Revolution. In the short term, its chief beneficiaries were municipal libraries, which in 1803 received (theoretically on deposit) the revolutionary spoils stored in warehouses: many such libraries were actually born out of this decree. In the long term, the chief victims of the Napoleonic system were arguably universities: not only had they lost their libraries, abolished in 1793 (not to be formally re-established until 1879), but they were regimented once and for all into a state educational structure that gave them neither the opportunity nor the funds to build research collections comparable to their British, Dutch, German, and, later, American counterparts. (Strasbourg, the only possible exception, is largely indebted in this respect to its having been under German rule between 1871 and 1918.) Until 1810, the surveillance of publications was left to the police, headed by the notorious Fouché, an arrangement that induced a self-censorship even more effective than outright repression. Nor was there any hesitation to resort to repression when necessary: in 1810, Fouché’s successor, Savary, was directed to seize and destroy the entire edition of Mme de Staël’s De l’Allemagne; its author was exiled. The new set of rules established in 1810 remained in place more or less until 1870. They officially reintroduced censorship, reduced the number of Parisian printers to 60 (later increased to 80), and made authorization to print or sell books subject to a revocable licence or brevet. Tight control was exercised by a Direction de la librairie, which proved so zealous that Napoleon had to dissociate himself from it publicly. A more positive and longer-lasting creation was the future Bibliographie de la France, reviving d’Ormesson’s plans. Characteristically, the Imprimerie nationale (‘Impériale’ for the time being) grew enormously, involving more than 150 presses and 1,000 printers by 1814. A splendid product of state intervention, the Description de l’Égypte, documenting the scientific aspects of Bonaparte’s 1798–9 expedition, was commissioned in 1802. The last of its 21 volumes (13 comprising plates), issued in 1,000 copies, came out in 1828.

The period associated with Romanticism witnessed what has been termed ‘the second revolution of the book’, namely, the appearance of a mass market. This was made possible by the progress of literacy as well as by technical innovation. Mechanization affected the paper industry, printing (with some resistance among workers, as a case of Luddism in the 1830 Revolution attests), and binding (see 11). Stereotyping became enormously important—Didot, in particular, exploited and systematized the discoveries of 18th-century pioneers such as François-Joseph-Ignace Hoffmann and L.-É. Herhan. Lithography made possible large press runs of high-quality illustrated texts, while the coloured woodcuts manufactured by Pellerin in Épinal not only remain forever associated with this Vosges city but also played a key role in the dissemination of the Napoleonic legend. Large printing plants flourished: Chaix in Paris, which prospered by printing railway timetables; or, in Tours, the equally famous Mame, specializing in religious literature, a field dominated by the figure of the Abbé Migne. Another mark of progress was the birth of ‘industrial’ distribution methods, facilitated after 1840 by the spread of railways and the growth of modern publicity methods. One consequence of these developments was the separation of the functions of printer and publisher—still often united in the first decade of the century (as in the case of the Didots), but almost universally kept apart by its end. On the other hand, the tradition of publishing houses owning and operating a bookshop remained alive throughout the century and beyond. Typographically, the only innovator was the Lyonnais Louis Perrin and his augustaux, inspired by Roman inscriptions, which in 1856 became the ‘Elzévir’ type popularized by Alphonse Lemerre’s imprints.

Balzac, a sometime printer himself, has left in his 1843 novel Les Illusions perdues a memorable account of the book world of the 1820s—from the traditional, family operation of David Séchard in Angoulême, threatened locally by enterprising, commercially minded competitors, to the new type of Parisian publishers and dealers, for whom poetry and the novel were above all a commodity to be bought and sold. The year 1838 typifies the liveliness of the book world: Louis Hachette, a successful supplier of primary school textbooks now in great demand following Guizot’s 1833 education laws, opened a branch in Algiers; the first novel to be serialized in the popular press, Dumas’s Le Capitaine Paul, appeared in Le Siècle; Labrouste drew the plans for the new Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève; and Gervais Charpentier launched his ‘Bibliothèque Charpentier’, which genuinely prefigures the modern paperback, and whose modest price (3.50 francs) compensated for its dense typography. The ‘Char-pentier revolution’, as it has been called, which did away with the elegant ‘Didot style’ that had dominated the previous 40 years, was quickly imitated. Bourdilliat & Jacottet dropped the price of their books to 1 fr., as did Michel Lévy, publisher of Madame Bovary (his brother Calmann later headed his house). By 1852, only fifteen years after the line from Paris to Saint-Germain opened, Hachette acquired the monopoly on French railway station bookstalls, creating a ‘Bibliothèque des chemins de fer’ the following year. Other successful careers of the period resulted in the establishment of long-lasting houses: Dalloz, Garnier, Plon, Dunod, Larousse. The mechanization of wood engraving led to a boom in children’s literature. Although the best-known names remain those of the comtesse de Ségur (a Hachette author) and Jules Verne (published by Hetzel), the phenomenon also benefited provincial publishers.

French Romanticism is associated above all with poetry and the novel, and to a lesser extent the theatre; but the greatest success of the period was a religious essay, Lamennais’s Paroles d’un croyant (1834). Its sales were boosted by its being immediately added to the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a fate it shared with Renan’s even more successful Vie de Jésus (1863), which sold more than 160,000 copies in its first year. The ‘consecration of the writer’ (Bénichou) in 19th-century France reached its apex with Hugo’s state funeral in 1885. This development began with the founding of the first writers’ associations: the Société des auteurs in 1829, followed by the Société des gens de lettres in 1837. Decades before the Berne Convention on copyright of 1886, these organizations were instrumental in securing the first bilateral agreement against piracy (with Belgium, 1852), and in having copyright extended to the surviving spouse (1866). Similarly, progress was achieved in the book world (including unionization) as a result of the founding of the Cercle de la librairie in 1847.

The general trend towards democratization that characterizes the 19th century had implications for the illustrated book, which had largely been a de luxe affair in the previous century. Although Delacroix’s lithographs for the second edition of Nerval’s translation of Goethe’s Faust (1828), today considered a landmark in book illustration, were a commercial failure, the technique was popularized in the 1830s by a new kind of illustrated press (Le Charivari, La Caricature), where Honoré Daumier and, especially, J. J. Grandville published their work. Grandville dominated the illustrated book of the 1830s and 1840s, much as Gustave Doré did in the 1850s and 1860s. A celebrated achievement of the Romantic period remains the 1838 Paul et Virginie published by Léon Curmer, with woodcuts and etchings by Tony Johannot, Louis Français, Eugène Isabey, Ernest Meissonier, Paul Huet, and Charles Marville. The greatest monument of the time, however, and one of lithography’s most beautiful products, is the series of Voyages pittoresques et romantiques de l’ancienne France edited by Charles Nodier and Baron Taylor, published by Didot in ten parts, each devoted to a French province, between 1820 and 1878. Géricault, Ingres, the Vernets, and Viollet-le-Duc, among others, participated in the project. Seven years after H. F. Talbot’s Pencil of Nature, the French ‘photographic incunable’ (Brun) was Renard’s Paris photographié (1853). Nevertheless, its appearance was anticipated by the two photographic plates—reproduced via the process invented by A. H. L. Fizeau—that were included in Excursions dagueriennes in 1842.

Since the French Revolution put large quantities of early and rare books on the market, the 19th century was the golden age of French bibliophilia, with Nodier, creator of the Bulletin du bibliophile, as its patron saint and J.-C. Brunet its founding father. The Société des bibliophiles françois was established in 1820. Among the collections dating from the period, few can match in splendour the one formed (largely in England) by the duc d’Aumale and now preserved at Chantilly.

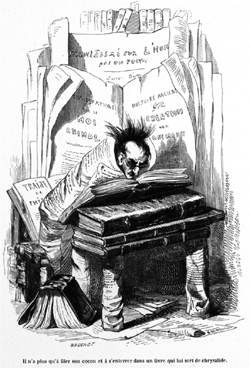

A bookworm, by J. J. Grandville, from Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (Paris, 1842) by P.-J. Stahl (P.-J. Hetzel) and others. The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford (Vat. FR. III. B. 4053, opposite page 327)

Considering their rapid rise at the end of the ancien régime, French libraries should have enjoyed a golden age in the 19th century as well. With exceptions—the Arsenal under Nodier (though more as a salon than from a professional viewpoint) and Sainte-Geneviève—they did not. Even the Bibliothèque nationale suffered from comparative neglect until space problems forced the renovation begun in the 1850s and completed in the 1870s. Municipal libraries, consolidating their revolutionary gains, did relatively better. Compensating in part for the lack of public investment, lending cabinets de lecture flourished in the early 19th century (more than 500 operated in Paris) and several different types of library appeared during the period, especially small, specialized institutional libraries established by learned societies, such as the Société de l’histoire du protestantisme français; chambers of commerce (created throughout the country between 1825 and 1872); and religious institutions (some of these were confiscated, once more, at the 1905 separation between Church and state). As a result of the parallel rise in industrialization and literacy, a growing concern for popular libraries manifested itself during the Second Empire. The Société Franklin, founded in 1862, devoted itself to this effort. The École des Chartes, possibly the century’s greatest legacy to librarianship, was founded in 1821 in order to train palaeographers and archivists. It was moved in 1897 to the new Sorbonne buildings.

The period 1870–1914 confirmed and accelerated the trends of the second book revolution. Although around 6,000 titles were printed in 1828, the figure had risen to 15,000 by 1889 and grew to about 25,000 by 1914. The growth was particularly spectacular in the newspaper and periodical press, finally liberalized by the law of 29 July 1881. Newspapers reached a circulation they were never again to equal: Milhaud’s Petit Journal was selling more than a million copies by 1891. In 1914, Le Petit Parisien was issued in 1.5 million copies, with Le Matin and Le Journal not far behind at 1 million each. After a relative decline in the 1870s, this boom affected nearly all sectors, perhaps most especially the novel. Thus, if the initial volumes of the Rougon-Macquart series sold moderately, the success of L’Assommoir in 1876 propelled Zola (a Charpentier author) to the highest print runs of any novelist in his generation (55,000 copies for the first printing of Nana in 1879). Yet these figures pale before those achieved by the book that has become synonymous with Third Republic ideology, the Tour de la France par deux enfants by ‘G. Bruno’ (nom de plume of Mme Alfred Fouillée). Published by Belin in 1877 and read by generations of schoolchildren, it sold more than 8 million copies over the course of a century. Another popular genre of the pre-1914 period, detective fiction, was born in 1866, when Émile Gaboriau’s L’Affaire Lerouge was serialized in Le Soleil. Its leading exponents in the early 20th century were Maurice Leblanc (his hero, Arsène Lupin, described as a ‘gentleman burglar’) and Gaston Leroux with his Rouletabille series.

New publicity methods soon affected literary publishing. They were used by the young Albin Michel to launch his first title, Félicien Champsaur’s L’Arriviste (1902), and by Arthème Fayard (a house founded in 1857) for its collections ‘Modern Bibliothèque’ (note the missing ‘e’ in the adjective) and ‘Le Livre populaire’, which had considerable success before 1914, thanks to a policy of combining large print runs (100,000 or more) and low royalties.

At the other end of the spectrum, French bibliophilia continued to flourish at the fin de siècle, as the names of the prince d’Essling, Édouard Rahir, and Henri Béraldi (founder of the Société des amis des livres in 1874) testify. French bibliophiles of the period, however, do not seem to have had much contact with the pictorial avant-garde of their age, which left disappointingly few traces on the book arts of the time. Little notice was given to such landmark works as Manet’s illustrations to Stéphane Mallarmé’s version of Poe’s The Raven (1875), L’Après-midi d’un faune (1876), and Poe’s Poèmes (1889)—also in Mallarmé’s translations—nor to Lautrec’s two remarkable productions, Clemenceau’s Au pied du Sinaï (1898) and Jules Renard’s Histoires naturelles (1899). The foresightful Ambroise Vollard tried to redress the situation at the end of the century. Mallarmé’s death in 1897 having interrupted his tantalizing project of Un coup de dés illustrated by Odilon Redon, Vollard’s first two books, Verlaine’s Parallèlement (1900) and Longus’ Daphnis and Chloé (1902), were both illustrated by Bonnard. Now considered the first masterpieces of the modern artist’s books, they were poorly received at the time. (Vollard printed them both at the Imprimerie nationale, an institution then in such turmoil that the French Parliament debated its abolition.) Vollard’s example inspired another pioneer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, whose first book, Apollinaire’s L’Enchanteur pourrissant (1909), with Derain’s subtly ‘primitivistic’ woodcuts, is another landmark; his Saint Matorel (1911), derided by contemporary livres à figures collectors, inaugurated Pablo Picasso’s glorious association with the illustrated book.

After the expansion of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the period beginning in 1914 was, in France as elsewhere, a time of crisis and renewal. World War I, during which restrictions halved paper supplies, was followed by a short boom in publishing during the 1920s. The so-called années folles were well attuned to the development of modern methods of book promotion. One of their early beneficiaries was Pierre Benoît’s novel L’Atlantide, a 1919 bestseller (a term soon adopted by the French) published by Albin Michel; the Académie française awarded it the Grand Prix du roman it had established the previous year. This new importance of literary prizes in the publishing world was signalled, also in 1919, by the controversy that ensued when the Goncourt went to Proust’s À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs in preference to Roland Dorgelès’s war novel Les Croix de bois. (A different kind of controversy had surrounded the creation of the Femina Prize in 1904—its all-female jury was a response to the Goncourt Academy’s perceived misogyny.) The Renaudot Prize, founded in 1926, was soon seen as open to the avant-garde: its early laureates included Céline and Aragon, whose publisher Denoël thus came close to rivalling Gallimard and Grasset. A fifth prize, the Prix Interallié, was created in 1930 and first awarded to Malraux’s La Voie royale. After more than three-quarters of a century, the same five prizes continue to dominate the French literary landscape.

If the late 19th century had seen a gap between bibliophilia and the artistic avant-garde, the first half of the 20th saw the triumph of the livre de peintre or livre d’artiste (artist’s book), with strong innovators following in Vollard and Kahnweiler’s footsteps: Albert Skira and Tériade in the 1930s and 1940s, Iliazd (Ilia Zdanevich), Pierre Lecuire, Pierre-André Benoît, among others, in the 1950s and after. By contrast with their 19th-century predecessors, Henri Matisse and Picasso, arguably the century’s two most important painters, were each involved in many book projects; Picasso throughout his career (he illustrated more than 150 books), Matisse for a relatively short period in the final part of his, both with magnificent results. No satisfactory discussion of their art—or of the art of the book in France between 1930 and 1970—can ignore their achievements in this field.

The 1920s and 1930s were a time of typographical success, led by the Imprimerie nationale and epitomized by the success of the Futura (or ‘Europe’) type launched by the foundry of Deberny & Peignot. The same decades also witnessed a renaissance of bookbinding design in France (which had begun in the art nouveau period), marked by the achievements of Henri Marius-Michel, Victor Prouvé, and Charles Meunier. An even more impressive group—under the aegis of dealers like Auguste Blaizot and collectors gathered in the association Les Amis de la reliure originale—was the generation of Paul Bonet, Henri Creuzevault, Georges Cretté, and Pierre Legrain. They were succeeded, after World War II, by the outstanding trio of Georges Leroux, Pierre-Lucien Martin, and Monique Mathieu. Their successor, Jean de Gonet, has been remarkable both for his efforts to democratize original bindings by using industrial leather (‘revorim’) and because, unlike them, he operated his own workshop rather than being strictly a designer.

World War II, when the country was occupied for more than four years, had dramatic consequences for the book world. Censorship was imposed by the Nazis (the notorious ‘Otto list’); shortages of paper more than halved production; ‘Aryanization’ measures affected individuals (such as the general administrator of the BN, Julien Cain, who was sacked by Vichy and later deported by the Nazis) and publishing houses—although Nathan managed to sell its shares to a group of friends, Calmann-Lévy was purchased and run by a German businessman and Ferenczi was put into the hands of a collaborator. The first two publishers were later revived, but the third never regained its prewar status. Yet, paradoxically, the four years of occupation coincided with a literary flowering, reading having become by necessity the chief cultural activity. The years following liberation confirmed the emergence of a new literary generation—that of Beauvoir, Camus, Queneau, and Sartre—which recaptured the kind of prestige enjoyed by 18th-century philosophes, a prestige reflected in their publisher, Gallimard.

For all its aberrations, the Vichy period also marked a return to the long French tradition of intervention in cultural matters, following the relative disengagement that had characterized most of the Third Republic. From this point of view, there was a continuity with the Fourth and Fifth Republics. Already in the 1930s, particularly in the shadow of the Depression, there was a growing concern that the state was not doing enough to support libraries or the book trade and that a politique de la lecture was in order. This was accomplished through a variety of government agencies working sometimes in harmony, at other times in competition. The cultural division of the ministry of foreign affairs, established in the early 1920s, subsidized French book exports (and was quickly accused of favouring Gallimard authors). A Caisse nationale des lettres, with representatives of the profession, was created in 1930 with a view to granting loans and subsidies—it became the Centre national des lettres in 1973 and the Centre national du livre in 1993. It too has not been immune to charges of favouritism. In the wake of the liberation, a Direction des bibliothèques et de la lecture publique was created within the education ministry (with Cain at its head). Since school libraries were not part of its responsibilities, it focused instead on the creation of a network of lending libraries called Bibliothèques centrales (renamed ‘départementales’ in 1983), which helped to reduce the cultural gap not only between Paris and the provinces but also between large cities and rural areas. School libraries began to receive serious attention in the 1970s. University libraries, however, remained (and still are) the poor relations of the French educational system, even as the French student population doubled over the same decade. The overwhelming success (particularly with students) of the Bibliothèque publique d’information at the Pompidou Centre, which opened in 1977, showed how keenly the lack of research facilities with open stacks and late and Sunday hours was being felt.

The Mitterrand government that came to power in 1981 proclaimed ambitious cultural policies (the official portrait of the president showed him with an open copy of Montaigne in his hands). One of its first measures was the imposition of a 5 per cent cap on book discounts, with a view to protecting independent bookdealers. The Direction du livre (created in 1975) and BN were placed under the authority of an expanded ministry of culture headed by Jack Lang. More subsidies were indeed available, but to what extent any of the official measures have affected continuing economic or cultural trends is debatable. The most enduring legacy of the Mitterrand years and, significantly, the most controversial of his grands projets remains the new, high-tech BnF, opened in 1996 after his death and named after him.

Economically, the trend towards greater corporate amalgamation, beginning in the 1950s, led, after the economic crisis of 1973, to the formation of three publishing giants: Hachette, which throughout the century had grown as both publisher and book distributor; the Groupe de la Cité, formed in 1988 and including Larousse, Nathan, the Presses de la Cité, Bordas, and the 4-million-member France-Loisirs book club; and Masson, the medical publisher, which had grown by absorbing Colin in 1987 and Belfond in 1989. The three became two when Masson Belfond was absorbed by CEP/Cité/Havas in 1995—to be resold to a different group six years later. Behind these two groups are larger financial entities, Lagardère for Hachette, Vivendi-Universal (originally a water-supply company) for the other. Following Rizzoli’s purchase of Flammarion, only five major Parisian firms, which themselves had absorbed smaller houses, remained independent by 2005: Albin Michel, Calmann-Lévy, Fayard, Gallimard, and Le Seuil. According to 2002 statistics, 80 per cent of all French book production came from the top 15 per cent of a total of 313 publishers. The same statistics revealed a significant decline of the workforce in the publishing sector (about 10,000, down from 13,350 in 1975), while the number of titles published (20,000) is lower than the figure for 1914. A very small number of titles represent a high percentage of the total sales, not necessarily at the lower end: Marguerite Duras’s L’Amant in 1984 and Yann Arthus-Bertrand’s photographic album La Terre vue du ciel in 2000 both sold more than 1 million copies each. Corporate mergers have also affected the book trade, with large chains like FNAC (itself now controlled by a major financial group) or non-traditional outlets (‘hypermarkets’) occupying a position of growing importance. Despite remarkable exceptions like Actes Sud—which, however, eventually opened offices in Paris—the trend towards amalgamation has reinforced the position of the capital, which at the beginning of the 21st century controlled about 90 per cent of production. One could qualify this picture, however, by stressing the viability of small or medium-sized specialized houses, such as L’Arche, devoted almost entirely to the theatre; or the relative health of religious publishing, dominated by the three Catholic houses of Bayard, Le Cerf, and Desclée de Brouwer.

Culturally, the most important event in French book history between 1945 and the advent of the Internet was the launching of the ‘Livre de poche’ series by Hachette and Gallimard (1953). This comparatively belated French answer to Penguin Books deeply affected book-buying and reading habits—a 20th-century equivalent of the ‘Révolution Charpentier’ in the 19th. Gallimard and Hachette were ‘divorced’ in 1972, when Gallimard created the Folio collection to reissue titles from its own considerable list.

Another notable postwar change has been the growth of children’s literature and the parallel development of children’s libraries since the first, ‘L’Heure joyeuse’, was opened in Paris in 1924 by a branch of the American Relief Committee. A landmark in this respect was the creation of the association La Joie par les livres in 1963. A private initiative, it led to the opening of a model children’s library in the Paris suburb of Clamart in 1965. In addition to specialized houses like L’École des loisirs (also established in 1965), many of the major publishers (Gallimard for one) opened a children’s department.

In a different sphere, the postwar period saw a resurgence, followed by a gradual decline, of censorship on moral grounds: Olympia Press and J.-J. Pauvert, publisher of Sade and L’ Histoire d’O, were prosecuted in the 1940s and 1950s, while the suppression of Bernard Noël’s Le Château de Cène was met with a public outcry in 1973. In popular literature, where detective fiction has continued to flourish, perhaps the most striking phenomenon has been the spread of comic books to the adult population, exemplified by the success of Goscinny and Uderzo’s Astérix series in the 1970s. The ‘bande dessinée’ is now a respectable genre with its museum and annual festival in Angoulême.

Traditional forms of book culture, however, are still very much alive at all levels. Evidence for this can be found at the academic level by the vitality of ‘l’histoire du livre’ (launched by the publication in 1957 of Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin’s L’Apparition du livre); at the bibliophilic level by the health of book collecting, nourished by the seemingly endless supply of material at auction or through the outstanding antiquarian book trade; and, in the population in general, by the qualitatively important place books and reading continue to occupy in the collective perception the French have of their own culture.

F. Barbier, Histoire du livre (2000)

P. Bénichou, The Consecration of the Writer, 1750–1830, tr. M. K. Jensen (1999)

[Bibliothèque nationale de France,] En français dans le texte: dix siècles de lumières par le livre (1990)

R. Brun, Le Livre français (1969)

R. Chartier and H.-J. Martin, eds., Histoire de l’édition française (3 vols, 1982)

A. Coron, ed., Des Livres rares depuis l’invention de l’imprimerie (1998)

DEL

L. Febvre and H.-J. Martin, The Coming of the Book, tr. D. Gerard (1997)

C. Hesse, Publishing and Cultural Politics in Revolutionary Paris, 1789–1810 (1991)

H.-J. Martin, Print, Power, and People in 17th-Century France, tr. D. Gerard (1993)

P. Schuwer, Dictionnaire de l’édition (1977)

M.-H. Tesnière and P. Gifford, eds., Creating French Culture (1995)