The History of the Book in Austria

JOHN L. FLOOD

Given Austria’s linguistic and historical ties with Germany, its book culture has inevitably been strongly influenced by its neighbour (see 26). Part of the Holy Roman Empire until 1806, Austria was for centuries dominated by the Habsburgs, who ruled until 1918. Under this dynasty, Bohemia and Hungary were united with Austria in 1526. In 1867 the double monarchy of Austria-Hungary was created, whose multi-ethnic population (51 million in 1910, with 2.1 million in Vienna) embraced not only German-speakers, but also the peoples of most of the now independent states of central Europe. Following World War I, the borders were redrawn, creating the (first) Republic of Austria, with Czechoslovakia and Hungary as independent states. In 1938, Austria was annexed to the German Reich, and in 1945 occupied by American, British, French, and Soviet forces until the Second Republic officially came into being in 1955. Today Austria’s population is c.8.2 million, of whom 1.6 million live in Vienna.

In the Middle Ages, book culture flourished in such monasteries as Salzburg (then belonging to Bavaria) and Kremsmünster, both 8th-century foundations, and later at Admont, St Florian, and elsewhere.

In 1500, the population of the area corresponding to present-day Austria was about 1.5 million. Vienna had c.20,000 inhabitants, Schwaz 15,000, Salzburg 8,000, Graz 7,000, Steyr 6,000, and Innsbruck 5,000. At that date, Vienna’s university (founded 1365), was a centre of humanist scholarship. The first printer in the city was Stephan Koblinger, who arrived from Vicenza in 1482 and stayed until at least 1486. Next came Johann Winterburger (active 1492–1519, producing c.165 books, including many editions of classical authors), Johann Singriener (1510–45, with c.400 books in various languages), and his partner, Hieronymus Vietor. In 1505 the brothers Leonhard and Lukas Alantsee established a bookshop in Vienna. The chief places of printing outside Vienna were Innsbruck (1547), Salzburg (1550), Graz (c.1559), Brixen (1564), Linz (1615), and Klagenfurt (1640). Yet, compared with Germany, the book trade in Austria was relatively underdeveloped. Austrian readers were principally supplied by booksellers from southern Germany, especially Augsburg.

In the early modern period, Austria experienced a series of crises. The economy (especially mining) was affected by the geo-strategic shift resulting from the discovery of the New World. Vienna and Graz were besieged by the Turks in 1529 and 1532 respectively, and the Turkish wars flared up again in 1593. Vienna was besieged once more in 1683. From the 1520s there was social unrest among the peasants, and religious life was shaken by the Reformation. The fear of Lutheranism led to censorship being imposed as early as 1528. Unlike in Germany, Protestant printing was never more than peripheral in Austria. The Counter-Reformation brought educational reform and renewal of intellectual life through the Jesuits, who also established printing presses (for example, in 1559 at Vienna), but it also meant the confiscation and burning of Protestant books (for example, 10,000 books at Graz in August 1600). Even in 1712, Salzburg householders had non-Catholic books confiscated during fire inspections of their premises.

Austria was not spared the economic decline associated with the Thirty Years War, and even between 1648 and the Napoleonic era there were more years of war than of peace. Although printer-publishers were found throughout Austria, their importance was generally limited and local; few of them attended the book fairs in Frankfurt or Leipzig. Hence Austrian authors seldom enjoyed European resonance. One exception was the preacher Abraham a Sancta Clara (1644–1709), whose works reached an international audience, chiefly through German reprints produced at Nuremberg and Ulm.

On 8 August 1703, Johann Baptist Schönwetter launched a daily newspaper, the Wiennerisches Diarium; renamed the Wiener Zeitung in 1780, it became the official gazette of the Austrian government in 1812, and is today one of the oldest continuously published newspapers in the world. In the 18th century, responsibility for censorship in Austria shifted from the Church to the state. Censorship was relaxed under Joseph II (emperor 1765–90), but the Napoleonic wars and the repressive policies of Prince Metternich led to its reimposition. Only after the 1848 revolution did matters improve.

As for the book trade itself, the demise of the exchange system for settling accounts and the insistence of Leipzig publishers on cash payments led to a boom in cheap reprints in southern Germany and Austria. A prominent figure in this regard was Johann Thomas von Trattner, court bookseller and printer in Vienna, who was actively encouraged by Empress Maria Theresa to issue reprints of German books.

Until 1918, the centres of publishing and literary life in the Austrian empire were Vienna and Prague. Writers associated with Vienna at this time include Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Karl Kraus (founder of the most important critical journal of the early 20th century, Die Fackel), while Prague produced Kafka, Rilke, and Franz Werfel.

During the 1930s, competition from German publishers became particularly intense. In 1934 the German government decreed that books sold abroad should receive a 25 per cent price subsidy. For Austria, this meant that German imports were now cheaper than home-produced books. In 1936 the Austrian government retaliated with a 3 per cent surcharge on foreign books, to provide a subsidy for Austrian publishers.

Between 1918 and 1938, some 90 publishing houses were founded in Austria, most of them short-lived, not least because of National Socialist policies following the Anschluss in March 1938. Among them were Phaidon Verlag, established in 1923—which became renowned for its large-format, richly illustrated, but modestly priced art books—and Paul Zsolnay Verlag, also founded in 1923, which specialized in literature. With the annexation, both these firms moved from Vienna to Britain. Phaidon is now an international concern; Zsolnay was re-established in Vienna in 1946. Other Austrian publishers and booksellers emigrated and built up successful businesses in the US: Friedrich Ungar, who founded the Frederick Ungar Publishing Company in 1940; Wilhelm Schab, who set up in New York in 1939; and H. P. Kraus.

The Nazis took immediate steps to control the book trade. Many Vienna publishers and booksellers quickly fell into line, while Jewish firms were liquidated and undesirable books impounded. More than 2 million books were removed from publishers’ stockrooms and bookshops; some were retained for ‘official’ purposes but most were pulped. Books were removed from libraries, too—only the Austrian National Library and the university libraries in Vienna, Salzburg, Graz, and Innsbruck were spared.

In 1945, the Allies imposed various denazification measures. A list of more than 2,000 prohibited books and authors was drawn up, and these were removed from public and private libraries—60,000 volumes from municipal libraries in Vienna alone were pulped. Pre-publication censorship was introduced, and schoolbooks were subjected to especially rigorous inspection.

Given that Leipzig, the centre of the German publishing industry, had been largely destroyed, there was initially great optimism in Austria that Vienna might become the centre of German-language publishing. However, paper was in short supply, printing equipment was antiquated, and the books produced had limited appeal. More new publishing ventures were founded on idealism than on a sound commercial basis. Moreover, in the early postwar years exporting to Germany was prohibited, which meant that the largest potential market was closed to Austrian publishers.

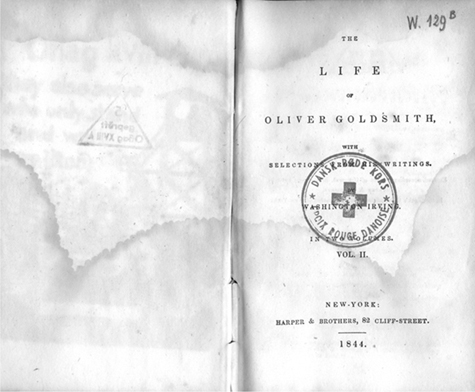

Prisoner-of-war reading: W. Irving’s Life of Oliver Goldsmith (New York, 1843–4) sent by the Danish Red Cross, examined by camp officials, and marked with a fine hand-printed bookplate as belonging to international prisoners in Oflag XVIIIa in south Austria. Private collection

Austrian publishers’ chief problems continue to be that the local market is too small and competition from powerful German rivals too intense. In the 1970s, while Austrian sales to Germany doubled, German publishers quadrupled theirs to Austria. Today, four out of every five books available in Austrian bookshops have been published in Germany, while German bookshops stock barely any Austrian titles. Of c.500 Austrian publishers today, more than half are based in Vienna. Two-thirds of them cater purely for the Austrian or regional market. A distinctive feature of Austrian publishing is the number of firms run by state organizations, the Catholic Church, and other institutions. The Österreichischer Bundesverlag (ÖBV), the largest publisher and a state enterprise until it was privatized in 2002, traces its origin to the schoolbook printing works established by Maria Theresa in 1772 to promote literacy. Firms such as Carinthia, Styria, and Tyrolia belong to the Church. Only three Austrian publishers—the ÖBV, the privately owned Verlag Carl Ueberreuter in Vienna, and the educational publishers Veritas in Linz—figure among the 100 largest German-language publishers. The continued independence of Austrian publishers has become more precarious since the country’s accession to the EU in 1995.

K. Amann, Zahltag: Der Anschluss österreichischer Schriftsteller an das Dritte Reich, 2e (1996)

N. Bachleitner et al., Geschichte des Buchhandels in Österreich (2000)

A. Durstmüller, 500 Jahre Druck in Österreich (1982)

H. P. Fritz, Buchstadt und Buchkrise. Verlagswesen und Literatur in Osterreich 1945–1955 (1989)

M. G. Hall, Österreichische Verlagsgeschichte 1918–1938 (1985)

—— Der Paul Zsolnay Verlag (1994)

—— Hall ‘Publishers and Institutions in Austria, 1918–1945’, in A History of Austrian Literature, 1918–2000, ed. K. Kohl and R. Robertson (2006)

—— and C. Köstner, “…allerlei für die Nationalbibliothek zu ergattern…”: Eine österreichische Institution in der NS-Zeit (2006)

A. Köllner, Buchwesen in Prag (2000)

J.-P. Lavandier, Le Livre au temps de Marie Thérèse (1993)

LGB 2