The History of the Book in Latin America (including Incas and Aztecs)

EUGENIA ROLDÁN VERA

Before the Spanish conquest, the people of the Americas had a wide range of systems for recording dates, astronomical information, and numerical data. Writing, in the form of pictograms that represent meanings with no relation to sounds, was used by virtually all indigenous groups throughout the continent. Good examples are known from the Olmecs, Zapotecs, Mixtecs, Purépechas, and Aztecs in Mexico, and the Incas in Andean South America. Although these people did use some developing phonetic signs, only the Mayas in Mesoamerica (the region comprising today’s Central America, southern Mexico, and central Mexico) developed a method of writing that represents phonetic language, from the 3rd century BC. Theirs was a system that combined logograms, phonetic syllables, and ideograms, and it was significantly more complex than the writing systems of later Mesoamerican civilizations. Both pictographic and phonetic scripts were carved in stones or bones, engraved in metal, and painted on ceramics; some scholars suggest that the still not fully deciphered Inca quipu computing system, consisting in assemblages of knotted strings, was a form of writing in its own right (see 1).

In Mesoamerica, information was also recorded on long strips of paper (made of the bark of the amate tree, a variety of the genus Ficus), agave fibres, or animal hides, which were folded like an accordion for storage and protected by wooden covers. These were the so-called codices or pictorial MSS, for many the Americas’ first proper ‘books’, which must have existed at least since the Classical Period (AD 3rd–8th centuries). Codices recorded astrological information, religious and astronomical calendars, knowledge about the Indian gods, peoples’ histories, genealogies of rulers, cartographic information (land boundaries, migration routes), and tribute collection. They were stored in temples and schools, and reading them was an activity that combined individual visual decoding with an oral explanation provided by priests or teachers. Other codices seem to have been used as visual mnemonic supports for traditional oral poetry, storytelling, and moral teachings given by parents to their children. Although most of these codices were burnt by the Spanish conquerors and missionaries after 1521, fifteen have been preserved, among them the codices Borgia, Fejérváry-Mayer, Laud, Vindobonensis, Nuttall, Bodley, Vatican B, Dresden, and Tro-Cortesiano. They all date from the 14th–16th centuries and belong to the Maya, Mixtec, Aztec, and other peoples from the Nahua group.

In spite of the large-scale destruction of indigenous culture caused by the Spanish conquest and colonization (16th–early 19th centuries), pictorial MSS remained a widespread form of recording information in Mesoamerica during much of the colonial period. Apart from the introduction of Western painting styles and the use of Spanish paper and cloth in addition to the indigenous amate, the most significant change in the post-conquest codices was the combination of painting with text written in the roman alphabet, which was introduced by the Spaniards. Most of these MSS were used for administrative purposes—they were made by indigenous local authorities as registers of tribute for the colonial rulers and proof of land titles in the context of litigation. Others were commissioned from indigenous scribes—or indigenous students trained in Spanish schools—in the first decades of Spanish rule by missionaries or colonial authorities interested in pre-Columbian thinking and traditions, history, and knowledge about the natural world. Whereas for the Spanish these codices were seen as a means to facilitate Christianization or colonial administration, for the Indians they constituted a way to preserve the memory of their culture. Nearly 430 codices of this sort have been preserved, the most comprehensive inventory of which was produced by Cline (Cline, 81–252). Some paradigmatic examples include: the Tira de la Peregrinación, the Codex Xólotl, the Matrícula de Tributos (which showed the tribute system of the Mexica empire), the Codex Bourbon and the Tonalámatl Aubin (divinatory almanacs), the Codex Mendoza (commissioned by the first viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, to inform the emperor Charles V (King Charles I of Spain) about the history, administration system, and everyday life of the ancient Mexicas), the Codex Badiano (an inventory of medicinal plants), and the Codex Florentino (a compilation of testimonies of the elderly about the divine, human, and natural world of the pre-Columbian Mexicans).

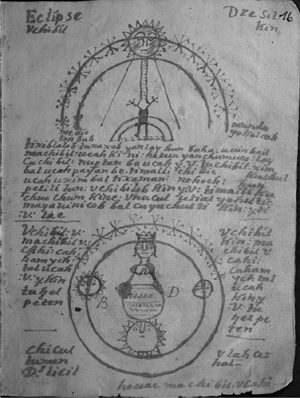

Spanish missionaries drew on the tradition of codices in their effort to convert the indigenous population to Catholicism. They created the genre of pictorial catechisms—known as ‘Testerian MSS’—which were small volumes of religious doctrine drawn with mnemonic figures, each of which represents a phrase, word, or syllable of the Christian text in indigenous language. Through them, the Indians were to memorize the dogmas, prayers, and commandments of the new religion, and by means of the images they would be able to communicate to the priests the sins they had committed. On the other hand, Indians also chose to use the roman alphabet to put down in indigenous languages information that had been previously orally transmitted in their cultures; the best examples of such texts come from the Maya region. The Popol Vuh, a history of the Mayan people (allegedly based on ancient codices and oral tradition), was secretly recorded (c.1550) in Mayan language but in roman alphabet by Indians who had attended Spanish missionary schools. Mayan priests followed a similar strategy in their writing of at least eighteen Chilam Balam books, in which they recorded the past, described the present, and stated prophecies for the future. These were collectively written MSS—with the main body of the text in Mayan language, often accompanied by drawings—copied and enlarged during the 16th–18th centuries, and passed down through the generations. This new arrangement epitomized the semantic transformation that took place with the introduction of new writing and reading practices in the colonial period: images, which in pre-Columbian codices were the powerful support for a predominantly oral culture, became a device meant to assist the understanding of written texts.

Notes on astronomy from the MS Chilam Balam de Chumayel (c.1775–1800). The MS relates the Spaniards’ conquest of the Yucatán. Princeton Mesoamerican Manuscripts (C0940). Manuscripts Division. Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. Princeton University Library

The persistence of the codex as a form for recording information in later stages of the colonial period is exemplified by the so called Techialoyan codices or ‘fake’ pictorial MSS, produced by some indigenous communities by the end of the 17th and the early 18th centuries. These were the communities’ property titles intended to prove their ancient possession of the land; they were drawn in a way that made them appear pre-Columbian and were used in litigation.

The Spanish and Portuguese conquerors brought with them not only the alphabet but also the printed book and, at least to some places, the printing press. The first books to arrive in America were the books of hours taken by Columbus’s men to the Caribbean islands, together with chivalric romances—such as the Amadís de Gaula, Cid Ruy Díaz, or Clarián de Landanis—and other fictional literature which contributed so much to feeding the conquerors’ imagination and their dreams of glory. Although the Spanish Crown attempted to prohibit the export of non-religious popular literature (of which more than 50 titles in at least 316 editions were printed in Spain during the 16th century) to the New World, its flow was steady throughout the first century of colonial rule.

Spain and Portugal attempted to control the production and reading of books in their colonies, both by issuing exclusive printing and trade rights and through the vigilance of the Inquisition. In 1525, the Spanish Crown gave the Seville-based publisher Jakob Cromberger absolute control over the book trade with New Spain (today’s Mexico, parts of the southwestern US, and Central America), a monopoly that was later transferred to his son Johann (Juan). Subsequently, the Spanish Crown granted exclusive publishing rights to selected printers in the colonies, especially for the publication of popular religious books; the rights also tended to inhibit the expansion of print in those territories. The Inquisition was meant to see that none of the books listed in the Index Librorum Prohibitorum—mainly heretical works, books of magic and divination and, in the 18th century, works of the French philosophes—made its way into the Americas. Yet this form of control was not very strict, and smuggling from Britain and France was common, especially in the last decades of Spanish rule. Furthermore, every book printed in Spanish America had theoretically to be examined by the Inquisition, the Consejo de Indias, or the Real Audiencia before publication, but this form of censorship was less effective in the control of print than the granting of exclusive printing rights. Portugal’s monopoly over Brazil was even stricter, for the colony was treated largely as an agricultural producer, and the production of manufactured goods, including print, was prevented by a series of laws until the mid-18th century.

Nevertheless, during colonial times c.30,000 titles were printed in Latin America, the most comprehensive accounts of which can be found in the bibliographies compiled by José Toribio Medina. Of all those titles, 12,000 were produced in New Spain. Indeed, during the 16th and 17th centuries, only the viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru, the richest colonies of the Spanish empire, possessed printing presses. The first printing press of the Americas was established in Mexico City in 1539, by Juan Pablos, a contractor of Johann Cromberger. In Lima, the first printing press was established in 1581, in the charge of the typographer Antonio Ricardo. With the exception of Puebla, in New Spain, and Guatemala City, which acquired their first printing presses in the 17th century (1640 and 1660 respectively), the rest of the Spanish and Portuguese colonial cities had to wait until the 18th or even until the 19th century to acquire a press: La Habana in 1701, Oaxaca in 1720, Bogotá in c.1738, Rio de Janeiro in 1747, Quito in 1760, Cordoba (Rio de la Plata) in 1765, Buenos Aires in 1780, Santiago de Chile in c.1780, Guadalajara and Veracruz in 1794, San José de Puerto Rico in c.1806, Caracas in 1808, La Paz in 1822, and Tegucigalpa in c.1829. In their South American reductions or settlements, the Jesuits attempted to make their own manual printing presses; but they managed this only in some cases. In Paraguay (a territory that comprises today’s Paraguay and parts of Brazil and Argentina), they put together a rudimentary handmade press towards 1705, with which they printed works in Spanish and in the Guarani language.

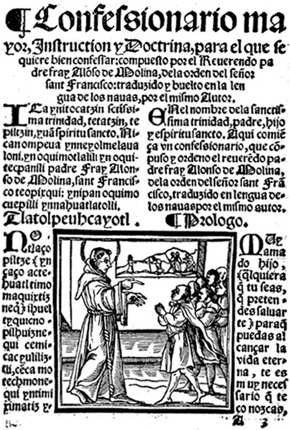

Peruvian and Mexican publishing in the 16th century was largely dominated by material used for the religious conversion of the Indians—catechisms, doctrines, and primers, as well as dictionaries and grammars of indigenous languages; prayer books and liturgical works, alongside compilations of laws, were also published from an early date. But none of the chronicles of the conquest or of the works of the missionaries about the history and traditions of the indigenous peoples was published in the Americas. Neither was a single chivalric romance published in the colonies, in spite of the genre’s popularity in those territories, thus indicating the efficiency of the Spanish publishers’ monopoly over certain kinds of works. In the 17th century, book production increased considerably; in New Spain alone 1,228 titles were published, in contrast with the 179 of the previous century. New genres were added to the works used regularly in Christianization: books about natural history and astrology such as the Repertorio by Henrico Martínez (Mexico City, 1606), chronicles of the activities of the religious orders in the respective colonies, and even literary works by authors such as Bernardo de Balbuena, the Mexican nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, and the Peruvian Juan de Espinosa Medrano (‘El Lunarejo’). The books imported from Spain were largely literary, with the dominant romances giving way to plays. Most of the books of this period, given their scarcity, high cost, and the low level of the general population’s literacy, ended up in the libraries of the universities of Mexico City, Lima, and Santo Domingo, in convents, or in the private libraries of members of the upper-level clergy and government officials.

A bilingual book for the conversion of the Indians in the New Spain: the Franciscan priest Alonso de Molina’s Confesionario Mayor en la lingua Mexicana y Castellana (Mexico, 1569). www.cervantesvirtual.com

In the 18th century, the production of print in Latin America increased threefold compared to the previous century (in New Spain at least 3,481 titles were published), partly thanks to the establishment of printing offices in other colonies. Works of religious doctrine and religious instruction continued to dominate, alongside religious chronicles and some historical and literary works. The main novelty of this century, however, was the emergence of the periodical, in the form of the monthly or weekly Gacetas. These publications contained news from the Crown; events in Europe and in the different colonies; notices about the arrival and departure of ships; edicts; and information about deaths, feasts, and lost objects. They became common in the second half of the 18th century and in the first decade of the 19th. The following titles exemplify this trend: Diarios y memorias de los sucesos principales (Lima, 1700–1711), Gaceta de México (1722, 1728–42), Gaceta de Guatemala (1729–31), Gaceta de Lima (1739–76), Mercurio de México (1741–2, 1764), Gaceta de La Habana (1764), Papel Periódico de La Habana (1789), Papel Periódico de la Ciudad de Santafé de Bogotá (1791–7), and the Gaceta de Buenos Aires (1810–21). Some gacetas focused specifically on scientific and learned matters, such as the Mercurio volante (Mexico City, 1772–3), by José Ignacio Bartolache; the Gaceta de literatura de México (1788–95), by José Alzate; and the Mercurio peruano (1791–4); these were intended not only for the scientific community but also for the enlightened general reader. A few daily newspapers such as the Telégrafo mercantil del Río de la Plata (1801–5) and the Diario de México (1805–17) appeared at the turn of the century. It is generally assumed that these periodicals helped form an incipient public sphere: communities of readers were created and provided with a space in which awareness of their own country and of the situation within the Spanish empire was moulded on a daily basis. Such writings also gave shape to a feeling of American (or creole) identity, which was reinforced by another kind of literature imported from abroad: works published by a handful of exiled Jesuits (expelled from the Spanish empire in 1767) about the history, the natural world, and the geography of individual Spanish-American countries. José Gumilla’s El Orinoco ilustrado (1741–4), Juan José de Eguiara y Eguren’s Bibliotheca Mexicana (1755), or Francisco Xavier Clavijero’s Historia antigua de México (1780) are the best examples of this kind of works.

In addition to such developments, educational reforms carried out in the Spanish empire in the last decades of the 18th century resulted in an expansion of basic literacy, thus expanding the market for print. Moreover, changes in maritime trade brought about by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars led the Spanish and Portuguese empires to lose some of their monopoly over the Americas. This facilitated the smuggling of French and British books to the colonies, which enlarged the libraries of Spanish-American creole elites and gradually made them more cosmopolitan.

The French invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 1808 unleashed a political crisis throughout the Spanish and the Portuguese empires that, between 1808 and 1824, eventually led to the independence of all their colonies in America (except Cuba and Puerto Rico). These events were accompanied by a print revolution. The Spanish king’s abdication and the dissolution of his empire resulted in the virtual disappearance of the printing monopolies, the end of the Inquisition, and the lifting of restrictions on the import of foreign books and printing presses. The need for rapid information about events in Europe and about the independence movements’ development stimulated the publication of periodicals, the appearance of new genres such as flyers and pamphlets, and the opening up of new spaces for public discussion and collective reading. The armies fighting for independence began to use portable printing presses, as they were advancing, to promulgate their manifestos and war reports. Moreover, the liberal 1812 Spanish constitution (endorsed by the colonies that had not yet become independent) established freedom of the press, a measure which was later incorporated into the liberal constitutions of all the newly independent countries—most of them republics. As a result of these developments, a total of 2,457 books and pamphlets were printed in Mexico alone between 1804 and 1820, and over that period the ratio of religious to political titles was inverted from around 80 per cent over 5 per cent in 1804–7, shifting to 17 per cent over 75 per cent in 1820 (Guerra, 288–90). In Venezuela, where the first printing press was introduced in 1808, 71 periodicals were published between 1808 and 1830.

In Brazil, the print revolution corresponded to Rio de Janeiro’s rise between 1808 and 1821 as the metropolis of the Portuguese empire. When the royal family fled Lisbon and settled in Rio de Janeiro, the king lifted the ban on printing and established the official Impressão Régia (Royal Press) there, which opened with a few presses imported from England. The Royal Press produced roughly 1,200 titles on a variety of subjects over the course of thirteen years. When Brazil declared its independence in 1821 and constituted itself as a liberal parliamentary monarchy (with Dom Pedro, the son of the Portuguese king, as its head), press freedom was declared. As a result, the official printing house’s monopoly ended; the number of printing presses grew exponentially; books could be imported without restriction; and local publishing flourished. Haiti, which had obtained its independence from France earlier, in 1804, experienced a similar expansion of print during the liberal regimes of the first two decades of the 19th century. The South American Liberator Simón Bolívar was reportedly provided with a printing press for military use by the Haitian President Alexandre Pétion in 1815.

During the early years of independence, the expansion of print with a more or less free press and a system without exclusive printing rights led to the formation of a rudimentary public sphere. In the painful process of nation-building, the publication of periodicals and pamphlets, the prime genres of the first half of the century, contributed to the circulation of opinion; some 6,000 titles, for example, were published in Mexico between 1821 and 1850. Throughout the continent, a cosmopolitan liberal elite of men of letters who combined political activity, legislation, and literary work played a disproportionate role in shaping local book production. Among the new types of publication were accounts of the wars of independence, personal apologias for political histories, discussions about the best way to organize the new countries, and literary works about the nature of America and about the ideal of pan-American unity. A Mexican, Fray Servando Teresa de Mier, a Cuban, José María de Heredia, and a Chilean, Andrés Bello, were among the prominent members of a group of writers who produced these sorts of work. The first national libraries, sponsored with public funds, were founded in the 1810s and 1820s (of Brazil and of Argentina in 1810, of Chile in 1813, of Uruguay in 1816, and of Colombia in 1823), largely on the basis of the collections of books confiscated from the Jesuits after their expulsion from the Spanish empire in 1767; but these institutions’ existence was interrupted throughout the century. However, political instability and economic grievances, as well as the high price of imported paper, hampered the development of profitable and long-lasting publishing industries, and only the so-called ‘state presses’, funded directly by governments for the publication of official periodicals, were able to survive continuously. Imported books, mainly Spanish editions printed in France or England, largely dominated the newly opened reading markets. These books were sold in different kinds of places (groceries, stalls in the marketplace, haberdashery shops, sugar depots, ironmongers, butchers, or post offices) and in a handful of bookshops, some of which were branches of well-established French booksellers—such as Bossange, Didot, Garnier—or of the London publisher and bookseller Rudolph Ackermann. British and French novels, together with treatises by European writers (mostly by Jeremy Bentham, Benjamin Constant, Destutt de Tracy, and Montesquieu), formed the majority of imported books. The reprinting of successful foreign works by local printers was also a common practice throughout much of the 19th century; before the Berne Convention on copyright in 1886, there were no bilateral agreements for the protection of publishers’ rights between France, Britain, or the US and any Spanish-American country (although some countries signed sporadic individual agreements on an individual basis).

From the 1840s to the 1860s, a handful of local printer-publishers achieved a degree of commercial success thanks to a combination of factors: the beginning of local paper production (in Chile, Brazil, and Mexico); a strategy of market diversification (periodicals, tracts, and coffee-table books), with publications for specific groups, such as women or children; and a policy of securing agreements with foreign publishers. The printer-publishers Ignacio Cumplido, Mariano Galván Rivera, and Vicente García Torres in Mexico and Santos Tornero in Chile are examples of such successful local publishing ventures. Moreover, the emergence of the popular serial novel (feuilleton) in newspapers towards the middle of the century changed the reading habits of large parts of the population (see 16). Historians maintain that Brazilian and Mexican serial novels, such as Manuel Antônio de Almeida’s Memórias de um sargento de milícias, published in the Correio Mercantil (1852–3), and Manuel Payno’s El fistol del diablo, in Revista científica y literaria (1845–6), contributed significantly to the growth of the reading public in their countries.

The consolidation of nation-states in the second half of the 19th century, together with gradual economic expansion, gave a new impetus to the publishing industry and shaped the emergence of new genres. This growth was reflected in the increased production of national histories and geographies, the foundation of more national libraries (of Puerto Rico in 1843, of Nicaragua in 1882, and of Mexico in 1867), and the quest for national literatures. Under the influence of romanticism, local book production was dominated by national themes, local landscapes, and regional human types; the colonial past became the subject of the increasingly popular historical novel. José Hernández’s Martín Fierro (Argentina, 1872–9), which became a bestseller, Jorge Isaacs’s María, a Cuban anti-slavery novel, (Colombia, 1867), and Ricardo Palma’s Tradiciones peruanas (1872–1910) are only a few examples of this nationalistic approach.

Moreover, although universal education was made a legal requirement from the early period of independence, considerable expansion of the educational system in most Latin American countries only began in the second half of the century. The growth in numbers of students had the double result of enlarging the reading public and of making textbooks a secure and fast-growing business after 1850—a business that was dominated by foreign publishing houses with branches in Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries. Indeed, the incursion of foreign publishers in the Latin American textbook market had started in the 1820s, when Ackermann exported, with limited success, large numbers of secular ‘catechisms’ of general knowledge (meant for both school and non-school audiences) to all Spanish-American countries. Later in the century, in the 1860s and 1870s, the American D. Appleton & Co. was more successful with exports of books to South America. But it was the French publishing houses Bouret, Garnier, and Hachette with branches for the printing and selling of their publications in Spanish-American countries and Brazil, that became the most important textbook suppliers in the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. The expansion in schooling was accompanied by the creation of larger numbers of public libraries (the prime example was in Argentina, where the reformer Domingo Faustino Sarmiento founded more than 100 public libraries after 1868). Towards the last decades of the 19th century, the influence of positivism encouraged the production of national bibliographies—of which the works by the Chilean Medina about all the Spanish-American countries are the foremost examples—and monumental national histories, such as the five-volume work coordinated by Vicente Riva Palacio entitled México a través de los siglos (1880), the ten volumes of Vicente Fidel López’s Historia de la República Argentina (1883–93), and Diego Barros Arana’s sixteen-volume Historia general de Chile (1894–1902). In terms of literature, the economic stability and relative prosperity of the last two decades of the 19th century favoured the development of modernism, a trend that was influenced by European cosmopolitanism and fascination for the ‘Orient’. Most of the works of Rubén Darío of Nicaragua, José Martí of Cuba, José Asunción Silva of Colombia, and Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera and Amado Nervo of Mexico were also published in Latin American countries other than their own, indicating that their movement’s cosmopolitanism was paralleled by the internationalization of the literary market. This broadening of the marketplace coincided with a trend across the region towards the professionalization of publishing, which became a separate business from printing and bookselling.

By the early 20th century, the growing Latin American book market was still dominated by French publishing houses—Garnier, Bouret, Ollendorff, Armand Colin, Hachette, Michaud, and Editorial Franco-Iberoamericana—plus some German (Herder), English (Nelson) and American (Appleton) houses. They all specialized not only in translations but in original publications in Spanish and Portuguese, and their superior technology and commercial policies allowed them to make large profits. However, after the outbreak of World War I French book exports to Latin America declined considerably, and Spain began taking over as an important supplier of books to the region. In fact, a few years after the 1898 Spanish-American war, when Spain lost Cuba and Puerto Rico, its last colonies in the continent, the former power tried to deepen its cultural ties with its past colonies, and successive Spanish governments saw in the book trade a vehicle for this. Thus, new international involvement, and the implementation of a fiscal regime more or less favourable for book exports to the region from the late 1910s to the 1930s, led Spain to become a power in Spanish-language publishing. By 1932, Spain’s book exports had reached US $1,214,000 (Subercaseaux, 148). Similarly, French involvement in World War I also resulted in a decrease of book exports to Brazil, which in turn favoured Portuguese exports to its former American colony.

On the other hand, the Mexican revolution (lasting from 1910 to c.1920) and the repercussions of World War I generated new intellectual trends across the continent; many thinkers were led to reconsider the cultural uniqueness of Latin America as a region in relation to other parts of the world. In the wake of nationalism and pan-Americanism, new genres flourished, especially novels with a social content and provocative essays. Intellectuals with political positions such as the Uruguayan José Enrique Rodó, the Peruvian José Carlos Mariátegui, the Mexicans José Vasconcelos and Alfonso Reyes, the Dominican Pedro Henríquez Ureña, and the Colombian Germán Arciniegas wrote extensively on the conceptualization of Latin America as a geographic, cultural, and spiritual unity. In parallel with intellectual debate, social reform—the attempt to integrate marginal sectors of the population, including Indians and Africans, into the new idea of the nation—resulted in creating a huge reading public for the first time in the history of those countries.

Although the 1930s were affected badly by the world economic depression, the outbreak of World War II in Europe coincided with the start of industrialization in most Latin American countries, with positive repercussions for the publishing industry. Indeed, the Spanish Civil War (1936–9) and World War II gave the emerging publishing industries of many Latin American countries an unexpected boost. A decrease in European book exports allowed domestic book production to increase, resulting in the creation of new publishing houses throughout the region. After 1945, the book industry followed the rapid pace of economic growth and industrialization, aided by strong government incentives.

In an era of state expansion and support for nationalism, culture was seen to be a government responsibility. In Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, favourable tax regimes for publishers (but not necessarily for booksellers) were inaugurated; in many cases, levies on imported materials for book production were lifted; the budget for public universities—which had their own publishing departments—increased, and the state itself even became the patron of some publishing houses. Prominent examples of state-sponsored publishers include: the Fondo de Cultura Económica, created as a government holding in Mexico in 1934; the National Book Institute in Brazil (1937); and the Mexican Comisión Nacional de Libros de Texto Gratuito (1959), established to publish set works for primary schools in the whole country. In addition, those countries’ publishing industries began to acquire the structure of modern enterprises, ruled by market forces: low production costs were achieved through high press runs (especially for pocket books and textbooks), which could be sold in Latin American countries with less developed publishing industries such as Chile, Uruguay, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and the Central American republics. As a result, Mexican book exports grew threefold between 1945 and 1955; by 1967 export levels reached US $11.5 million. Yet the most spectacular growth was experienced by the Argentinian publishing industry, for which the period 1938–55 is known as ‘the golden years’: its exports went from US $20,000 in the 1940s to nearly US $200 million in the 1960s (Subercaseaux, 147). By 1960 Argentina had some 160 publishing houses, not counting the printing departments of ministries, universities, and public cultural institutions. Brazil, which had started exporting books to Portugal in the late 1920s (mainly through the publishing house Civilização Brasileira), also saw a great increase in that trade between 1958 and 1970, from US $54,000 to US $2.4 million (Hallewell, 208).

By the 1960s, Latin American publishers also helped to expand the population’s reading habits by diversifying distribution. Instead of relying only on bookshops (which were still limited in number), they reached out to stationers, post offices, corner shops, and other kinds of popular outlets. This strategy, which was initiated successfully by Monteiro Lobato of Brazil in the 1910s and 1920s, was later put into practice by the Argentinian Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires (EUDEBA) and the Centro Editor de América Latina. Among other factors, these measures contributed to the consolidation of the internal market from the 1950s through to the 1970s.

State support came later (reaching its peak in communist Cuba, where all publishing houses were state-related and publishing was controlled by the government) or was limited in other Latin American countries; but on the whole the entire region experienced a growth in book production and consumption during the mid-20th century. It was precisely at this time of the Latin American publishing industry’s expansion that literary production grew and came to be recognized internationally as original and characteristically ‘Latin American’. With a combination of influences from early 20th-century surrealism, an interest in social topics, and the consciousness of a distinct Latin American cultural identity, poetry and fiction created new kinds of realism, in particular ‘magical realism’, metaphysical tales, and other kinds of fantastic literature. Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, Gabriel García Márquez (all of whom won the Nobel Prize for Literature), Miguel Angel Asturias, Julio Cortázar, Jorge Luis Borges—to mention only the best-known authors—produced their most important works between the 1940s and the 1960s. Their rapid rise to international fame was assisted by the peak in production and international trade reached by Latin American publishing in the period.

Complementing state support for the production and reading of books, UNESCO in 1971 created a Regional Centre for the Promotion of the Book in Latin America and the Caribbean (CERLALC), situated in Bogotá; members of the centre were Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Spain, Uruguay, and Venezuela. CERLALC’s aim was and is to promote the production, circulation, distribution, and reading of books in Latin America. Its design incorporates legal frameworks for free trade in books; it encourages regional governments to sign international conventions concerning copyright and against piracy; it initiates reading campaigns and training for professionals in the book industry. CERLALC also monitors aspects of book production and circulation in most Latin American countries, about which it publishes quantitative material and qualitative essays on its website, and in books, newsletters, and journals. As a result of CERLALC’s efforts, a number of Latin American countries issued so-called ‘Book Laws’ from the 1970s to the 1990s, which (taking as a model the Spanish book law of 1967) attempt to create legal and fiscal frameworks favourable for the production and circulation of books, as well as for the protection of authors’ rights. Yet these laws, while tending to privilege author’s and publishers’ rights, have done little to help booksellers.

Despite such legal measures, in the second half of the 20th century the Latin American publishing industry developed unevenly and suffered important setbacks. Argentina’s and Mexico’s primacy in the Spanish book trade were somewhat curtailed by Spain’s renewal in the 1950s and 1960s; indeed, by 1974 Spanish book exports had reached US $120 million (Subercaseaux, 148). The bloody military dictatorships of the 1950s–1980s that quashed vigorous social movements in Nicaragua, Paraguay, Guatemala, Haiti, Bolivia, Uruguay, Chile, and Argentina imposed tight censorship and control over the importing, production, and reading of a large number of books. Ill-considered policies in other countries ended up affecting the book industry or the business of bookselling: for example, a protectionist national policy towards papermaking in Mexico resulted in higher production costs for books. In addition, the fall in oil prices, precipitating a financial crisis that led to cycles of hyperinflation, devaluation, and economic recession in most of the region during the 1980s actually reduced the population’s income, increased book production costs, and led to declining book sales. From 1984 to 1990, for example, Argentina produced 18 per cent fewer titles.

By the mid-1990s, the return of democracy in most Latin American countries and trade liberalization stimulated the circulation of books throughout the region, but it took away some of the direct state support of the publishing sector; in some countries, this resulted in increased retail prices for books. An imported book in Peru in the 1990s, for example, cost 40 per cent more than in its country of origin, because of the high taxes imposed by a government needing to increase its revenues. By 1999, Brazil was publishing 54 per cent of the total number of books in Latin America, Argentina 33 per cent (11,900 titles), Mexico 29 per cent (6,000 titles), and Colombia 11 per cent (2,275 titles) (UNESCO). With the exception of Argentina and Chile, school textbooks were the dominant genre in all Latin American countries.

National unity was now no longer a reliable guide for understanding the publishing industry. A new phenomenon, the result of globalization, was the merging of transnational publishing groups and the integration of Latin American and European publishing houses. Groups such as Planeta, Santillana, Norma, Random House, Mondadori, and Hachette absorbed the most successful publishing houses and operated with branches in six or more countries. Such consolidation led to a reduction in the number of independent publishers, and of publishers with a specific cultural agenda. Most of the conglomerates made their money in the secure textbook market; reduced costs by producing in countries where materials and labour were cheap; published large numbers of editions of established authors and relatively few editions of new works; and aided their distribution by using mass media they also owned. For its part, the Mexican Fondo de Cultura Económica, which still enjoyed government subsidies, became one of the strongest non-textbook publishing houses by opening branches in Argentina, Colombia, Brazil, Peru, Guatemala, Chile, and Spain.

In the first decade of the 21st century, the trend towards the transnational merging of large publishing houses has persisted. Spain recovered its dominant position as provider of Spanish-language books: by 2005 it produced 39.7 per cent of all Spanish books sold in Latin America, whereas Spanish-American countries accounted for 40.2 per cent of sales. The biggest Latin American publishers of books in Spanish continued to be Argentina (27.1 per cent), Mexico (19 per cent), and Colombia (16.3 per cent), followed by Peru (6.1 per cent), Venezuela (5.9 per cent), Chile (5.6 per cent), Ecuador (4.3 per cent), Costa Rica (3.8 per cent), and Cuba (2.8 per cent) (SIER). Given that school textbooks were still dominant—with the significant exceptions of Argentina and Chile, where general-interest books still prevailed—and considering that the school population remained stable, the region’s book industries continued to thrive. However, the main problem appeared to be distribution: large numbers of books remained unsold, booksellers had few incentives to innovate, and the big publishing groups relied on discount bookshops or supermarkets to sell their products.

Finally, the numerical domination of textbooks in book production was also suggestive of the poor reading habits of the adult Latin American population—a subject that has become a major concern in studies carried out since 2000. Although varied in scope and methodology, these investigations seem to suggest that, in spite of relatively high levels of basic literacy, the number of books read per capita in Latin American countries is very small. According to UNESCO, Mexicans read on average less than 1 book per year (although a government study from 2003 raised that number to 2.9), and only 2 per cent of citizens regularly bought a newspaper; Colombians read an average of 1.6 books, Brazilians 1.8, and Argentinians 4. In countries such as Mexico and Brazil, where there were wide social divisions, there has been a persistent pattern of polarization between groups of the population who read many books each year and groups who read nothing. A study carried out in Mexico in 2001 about the population’s reading habits revealed that the most widely read ‘book’ was the weekly adult comic El libro vaquero (The Cowboy Book), of which 41 million copies were bought each year—18 million copies fewer than in 1985. Whether such a decrease indicates a change towards more sophisticated reading habits, declining enthusiasm for what popular adult comics offer, or a decrease in reading altogether awaits further determination.

Centro Regional para el Fomento del Libro en América Latina y el Caribe (CERLALC), www.cerlalc.org, consulted Aug. 2007

CERLALC, Producción y comercio internacional del libro en América Latina (2003)

H. F. Cline, ed., Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources, Handbook of Middle American Indians, vol. 14, part 3 (1975)

J. G. Cobo Borda, ed., Historia de las empresas editoriales en América Latina (2000)

R. L. Dávila Castañeda, ‘El libro en América Latina’, Boletín GC, 13 (Sept. 2005), www.sic.conaculta.gob.mx/documentos/905.pdf, consulted Aug. 2007

V. M. Díaz, Historia de la imprenta en Guatemala (1930)

J. L. de Diego, Editores y políticas editoriales en Argentina (2007)

Facultad de Filosofía (UNAM), Imprenta en México, www.mmh.ahaw.net/imprenta/index.php, consulted Aug. 2007

A. Fornet, El libro en Cuba (1994)

M. A. García, La imprenta en Honduras (1988)

F. X. Guerra, Modernidad e independencias (1993)

L. Hallewell, Books in Brazil (1982)

T. Hampe Martínez, ‘Fuentes y perspectivas para la historia del libro en el virreinato del Perú’, Boletín de la Academia Nacional de la Historia (Venezuela), 83.320 (1997), 37–54

I. A. Leonard, Books of the Brave, 2e (1992)

M. León Portilla, Códices (2003)

J. L. Martínez, El libro en Hispanoamérica, 2e (1984)

A. Martínez Rus, ‘La industria editorial española ante los mercados americanos del libro’, Hispania, 62.212 (2002), 1021–58

J. T. Medina, Biblioteca hispano-americana (1493–1810) (7 vols, 1898–1907)

I. Molina Jiménez, El que quiera divertirse (1995)

E. Roldán Vera, The British Book Trade and Spanish American Independence (2003)

D. Sánchez Lihón, El libro y la lectura en el Perú (1978)

SIER (Servicio de Información Estadística Regional), Libro y desarrollo (2005), www.cerlalc.org/secciones/libro_desarrollo/sier.htm, consulted Aug. 2007

L. B. Suárez de la Torre, ed., Empresa y cultura en tinta y papel (2001)

B. Subercaseaux, Historia del libro en Chile (1993)

E. de la Torre Villar, Breve historia del libro en México, 2e (1990)

UNESCO Institute for Statistics, ‘Book Production: Number of Titles by UDC Classes’ (2007), www.stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/tableView.aspx, consulted Aug. 2007

H. C. Woodbridge and L. S. Thompson, Printing in Colonial Spanish America (1976)

G. Zaid, Los demasiados libros (1996)