Wilhelm II’s sense of the contrast between England and Germany at the close of his grandmother’s long reign was hubristic, but it was not entirely wrong.

Back in the 1820s, Germans had come to England to observe and learn from a country that was deploying a combination of engineering skills, industrial power, a formidable navy and a surge of entrepreneurial spirit to transform itself into a super-power. During the first years of the twentieth century, it was the English who were sitting up to take note of the fact that Krupp, employing over 20,000 people at its Essen works, had become the world’s largest industrial company; that the north German shipyards at Danzig, Hamburg, Kiel, Wilhelmshaven and beautiful, Parisian-styled Stettin were on target to produce (at the urging of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz) thirty-eight battleships by 1919; that the Stettin-built Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse (named for Wilhelm I) was both the world’s first four-funnel transatlantic liner and a pioneer user of the Marconi wireless system for transmitting rescue messages; and that Albert Ballin, taking charge of the great Hamburg-Amerika line in 1899, was overseeing the launch of the world’s first cruise ship, proudly named for the Emperor’s daughter: Prinzessin Viktoria Luise. In 1902, it may also have been wistfully noted that Germany had a vigorous, morally upright and relatively youthful leader, while England was led by a stout, indolent and philandering bon viveur whose best-known source of pleasure (next to love-making and gambling) derived from the cigars named in his honour.

Moral rectitude did not save Wilhelm II from being mocked, at home and abroad, both for his lack of culture and for his faith in the power of official art to inspire and uplift the German people. It was with this goal in mind that the Emperor presented the city of Berlin, in 1901, with his own addition to a handsome boulevard that had been constructed back in 1896, to honour Germany’s military triumphs and to give pleasure to Sunday strollers in the Tiergarten park. The original Siegesallee had been well received; the Emperor’s addition of almost a hundred marble statues, with prominent placing for his own Hohenzollern forbears, was ridiculed as ‘Puppets’ Alley’ or the ‘Plaster Walk’. Wilhelm, undaunted, used his opening of the transformed boulevard to express imperial disapproval of ‘ugly art’ (in comparison to a double-banked row of quasi-classical figures). Ugly art, in Willy’s opinion, included the dangerously gloomy works of Cézanne, van Gogh and Edvard Munch that were being simultaneously displayed in the city by the Berlin Secession group, led by the great Impressionist painter Max Liebermann, and the dealer Paul Cassirer. What, the Emperor Wilhelm demanded, was the point of increasing people’s misery by showing them such dreary work, when the purpose of art was to raise people’s hopes above their modest expectations?1

The new Siegesallee was derided in Berlin, as were the Emperor’s views on modern art. Neither were the Emperor’s efforts to burnish his country’s image as a dynamic modern power helped, in the sphere of music, by Willy’s old-fashioned preference for Verdi and Gounod over Wagner, for whose work his appreciation was confined to borrowing the thunder motif from Das Rheingold for the horn of the imperial automobile.

Wilhelm’s philistinism did not equip him well for his dream of turning Berlin into the German Athens. It was Wilhelm, nevertheless, who presided over the gradual transformation of his home city from a dusty collection of military parade grounds into an elegant metropolis of broad streets, handsome department stores, new theatres and the smart restaurants at a precursor of which an astonished Matthew Arnold, lunching out in Berlin in 1885, had found himself sharing a table with two elegantly dressed tarts. Such a triangle, by the time that Berlin’s new Adlon Hotel opened its doors in 1907, would have widened no Prussian eyes at all.

The spirit of Berlin in 1902 was, despite lingering traces of an older world, keeping company with the 43-year-old Emperor’s jaunty sense of himself as ‘a man of the future’. London, by contrast, seemed locked, together with its new but ageing king (Edward was Wilhelm’s senior by eighteen years), into the past.

The past – that Pickwickian England so dear to the Emperor himself – held considerable power over German Anglophiles. The attractions of foxhunting in the Shires had seduced other German grandees besides Hansel Pless’s two Hochberg uncles to settle in England; many others paid regular visits. (One German officer claimed to know Yorkshire’s hunting fields well enough to name every blacksmith’s forge in the three Ridings.2) Count Friedrich Schulenburg, posted to London as a military attaché from 1902–06, was sufficiently bewitched by English ways to persuade his wife, Freda Marie von Arnim, that their children must be granted the sense of a dual heritage. Life at Tressow, the Schulenburgs’ Mecklenburg manor house, was effortlessly bilingual; their daughter Tisa remembered English books and German books being read as interchangeably as the two languages of this large and lively household were spoken.

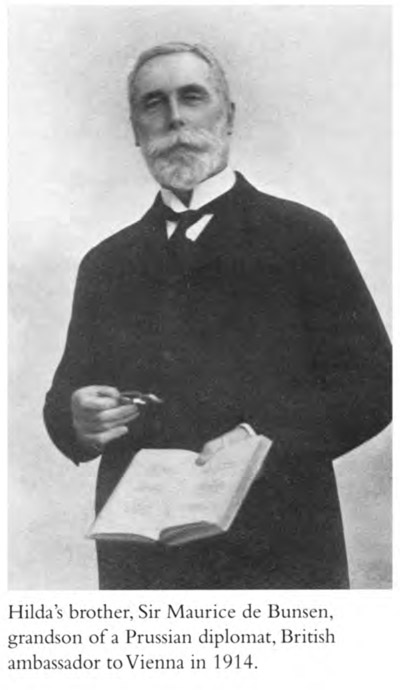

The wish to maintain a bond between Germany and England was most easily granted to the families of people like Hansel Pless, the Schröders and Hilda Deichmann, who were lucky enough to have inbuilt connections to both countries.

The author Robert Graves belonged to this privileged group. Visiting Laufzorn, his grandparents’ atmospheric manor house in Bavaria, during the long Edwardian summers of his early boyhood, Graves formed a keen respect for the bushy-haired old gentleman who was greeted by a warm ‘Grüss Gott, Herr Professor!’ when they drove out from his home and through the neighbouring villages.

Admired by young Robert for the atheism and rebelliousness of his early years, when his part in the Prussian uprisings of 1848 forced him to seek refuge in England, Heinrich von Ranke had studied medicine in London. Having served as a regimental surgeon at the Crimea, von Ranke went on to supervise paediatrics at the German Hospital in Dalston, while helping to set up the Great Ormond Street Hospital for children. Subsequently, having married the ‘tiny, saintly, frightened’ Danish daughter of the Greenwich astronomer, Graves’s grandfather returned to Bavaria. Here, in the process of becoming one of Munich’s most eminent paediatricians, von Ranke acquired Laufzorn and developed the habits of a respected country squire, while insisting – like Wilhelm II, whom he greatly admired – that his children should speak English in their family life, and look to England always as ‘the centre of culture and progress’.3

The warm feelings for England that Graves found among his German cousins endeared them to him. So, too – although Graves described German as a language in which he felt instantly at home – did the fact that his Bavarian cousins were fluent in English. Setting those benefits aside, it’s still hard to overstate the sense of settled contentment conveyed in Graves’s wistful recollections of those early summers in Germany: they were, he wrote, ‘easily the best things of my early childhood’.

The rural arcadia evoked by Graves was grounded in simple, accessible experiences: picking fruit in an orchard filled with greengages and plums; jumping on springy hay in a high, raftered barn; picking mushrooms in the woods; diving under a waterfall in the bright green Isar; paying visits by train to a castle up in the Bavarian Alps, where an eccentric great-uncle (Baron Siegfried von Aufsess) teased the credulous young visitors with craftily placed chocolate drops among the pathway pebbles that he urged them to devour.

All sounds innocuous and almost bland, until we remember that Graves was writing in 1929, and that he had fought against these same cousins in the war. Peppering the benign accounts of a distant past are reminders of the aftermath. Uncle Siegfried, serving on the Emperor’s staff of officers, was killed and lost. His body was never recovered. Wilhelm, a favourite cousin and a dab hand at picking off mice in the attics with his airgun, was ‘shot down in air battle by a schoolfellow of mine’. Conrad, another cherished cousin, with whom Graves remembered having gone skiing near Zurich in January 1914, is described as ‘a gentle, proud creature, chiefly interested in natural history [and] studying the habits of wild animals; he had strong feelings against shooting them’. Conrad von Ranke, so Graves tells his readers, went on to win the Blue Max (the German equivalent of the Victoria Cross), for his bravery. ‘Soon after the war ended, a party of Bolsheviks killed him in a Baltic village, to which he had been sent to make requisitions.’4 Looking back across ten traumatised years, Graves made no attempt to conceal his bitterness at the futility of war; at the pointlessness of Conrad’s death; at the horror for any soldier of having known – and loved as part of his own family – the enemy he was under orders to destroy. The experience was not an unusual one; Graves’s compellingly bitter war memoir, Goodbye to All That, describes a company mess in which the majority of British officers had German mothers or naturalised German fathers.

Robert Graves, born in 1895, belonged to a younger generation of Englishmen than Ford Madox Ford. Their bond was the dilemma of belonging to families with a dual heritage.

Ford, as buttercup-haired and blue-eyed as his father, the Wagnerian music critic Franz Hüffer (a name that had been swiftly exchanged for the more English-sounding Francis Hueffer), was seven years old in 1880, when he was despatched from home to learn German at a private school in Folkestone. Married at eighteen to Elsie Martindale, two years after the loss of his beloved father, Ford’s affair with Elsie’s sister led to social ostracism. In the autumn of 1904, following a nervous breakdown, Ford left England for five months, to make the acquaintance of his father’s Münster-based German family and to discover – between some eccentric courses of spa treatment recommended by his sympathetic cousins for three further nervous collapses – what the intelligent, unhappy and highly strung young writer described in his letters to England as a most wonderful sense of having come home.

Aside from his breakdowns, Ford was exceptionally happy in Germany; writing (somewhat tactlessly) to his wife and to their friend Olive Garnett, he compared the sorrowful rootlessness that he had come to feel in England (‘the tremendous feeling of loneliness and the end of the world that I had latterly’) with the sense – one that was novel to him, and quite delightful – of being accepted. ‘I am treated here like a duke,’ Ford told Olive Garnett. ‘. . . I feel I’m really liked and understood by everyone.’5

In 1906, Ford paid a second visit to Germany, taking Elsie and their young daughters from Heidelberg to Münster, where the girls, following their father’s own earlier conversion and with the warm approval of their Hüffer relations, adopted the Catholic faith.

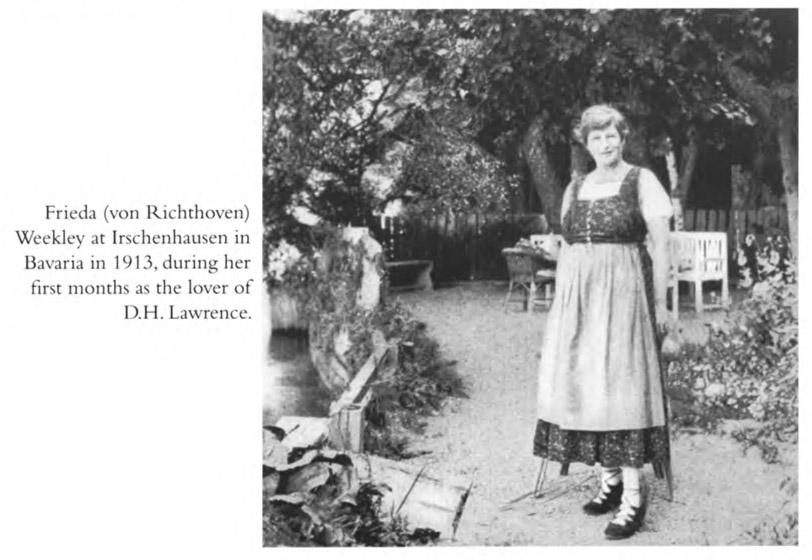

Four years later, while visiting Germany in the summer of 1910, Olive Garnett’s son David bumped into a faultlessly dressed Ford enjoying a Rhine tour in the company of his mistress, Violet Hunt. Conducted to Nauheim, the beautiful Jugendstil spa created under the patronage and close attention of Ernst of Hessen-Darmstadt, Hunt was struck by the gentle Grand Duke’s courteous manner; Ford’s pious Aunt Emma, less politely, refused to let her nephew’s lady friend enter her German home.

Violet was at her lover’s side again later that year when he paid a memorable visit to Marburg Castle, the setting for Luther’s unfaltering defence of Christ’s corporeal presence in the communion sacraments. Marburg gave Ford the setting for a key scene in the celebrated novel that he published five years later.

The Good Soldier was written and published in wartime. No hint appears in the novel of the author’s own German connections. Instead, the depth of Ford’s love for the nation to which he half belonged is artfully submerged in a cast of American and English protaganists who, staying at Nauheim at the turn of the century and mired in the unhappy complexities of their personal relations, respond to their surroundings only as tourists. Dowell, the unreliable narrator, views his surroundings with eyes that reject – or are incapable of seeing – any beauty in a German landscape. If Ford felt any lingering affection for the country he had once looked on as his true home, writing the novel that he had first wanted to call The Saddest Story seems to have helped him to kill it.

The advent of war ended Ford’s wish to connect himself to the Münster Hüffers and even to the German writers among whom he had once felt so happily at ease. In 1919, he relinquished the surname Hueffer; France, not Germany, would become his chosen home in a Europe to which the newly named Ford Madox Ford belonged, by temperament and blood, more closely than to the England of which he wrote, increasingly, with the romantic, idealising pen of a visitor from abroad.

In March 1905 – the year after Ford’s first visit to Germany – 26-year-old Morgan Forster arrived at Nassenheide, the Pomeranian schloss near Stettin to which he had been invited from England as a tutor to the children of Count Henning von Arnim, a tall, balding, impecunious – and cheerfully unliterary – Prussian landowner, and Elizabeth Beauchamp, his tiny, energetic and intensely literary Australian wife.

Forster had never been to Germany before; his first impressions of the celebrated setting of Elizabeth and Her German Garden (Countess von Arnim’s first and massively successful book had been anonymously published in 1898) were not good. Recalling his arrival, over fifty years later, Forster described how a farm worker had led him through a muddy farmyard to a dimly lit house at which, until Elizabeth herself hurried down to greet him, the newcomer was received with bewilderment (a German house-maid, not an English tutor, had been expected at the schloss).

The homely gabled manor house of Nassenheide won Forster’s heart during his four-month stay there, as did its inhabitants. The Count, despite an unnerving fondness for rinsing his false teeth during meals, proved both kind and courteous; the German tutor already in residence was a jovial beer-drinker; the pupils were entertaining and playful. One daughter, Trix, when asked by Forster to write an essay upon which country she would wish to win if England and Germany went to war, answered that she would not care: ‘I should run away as fast as I could.’6

Elizabeth herself lived up to her self-chosen motto: parva sed apta: small but effective. Indomitably competent and hard-working, she wrote twenty-one books, read voraciously and spoke her husband’s tongue well enough to pass as a native. Elizabeth was also, according to Forster, a merciless tease and disciplinarian who, after informing the young tutor that his work-in-progress made her want to take a bath, ordered him to finish it.

That book, Forster’s first novel, was Where Angels Fear to Tread, in which no hint of his German experiences can be detected. In 1908, back in England and with two further well-received novels to his name, Forster began work upon a fourth. He called it Howards End.

It is possible to interpret the story of the German Schlegels, the British Wilcoxes and Howards End (the house that binds them uneasily together) as an anti-war book. Forster’s novel also offers a personal tribute to the country that had so enchanted him during the months he spent at Nassenheide, visiting pretty, elegant Stettin and exploring the birch woods and the broad fields that stretched away from the windows of the Pomeranian manor house.

Criticisms of Germany, despite Forster’s fond recollections of life with the von Arnims, were not withheld. Mr Schlegel, looking wistfully back to the gentle world of the little princely courts and denouncing the new spirit of pan-Germanism, is endorsed in a way that suggests Forster himself may have shared the old-fashioned outlook of his former Prussian employer. Two haughty Schlegel cousins, visiting England from Stettin, are ridiculed for their firm belief in Germany’s God-given right to rule the world; another visitor, Frau Architect Frieda Liesecke, does not show to advantage when, invited to admire the Schlegel sisters’ favourite view across the Solent to the Isle of Wight, she registers only a muddy harbour (Poole) and the dreary bulk of distant hills.

Forster balances his mockery of the visitors against the ardent sincerity of the Schlegel girls, proudly described by their German-hating aunt, Mrs Munt, as ‘English . . . English to the backbone.’7 In fact, while belonging wholly to neither country, Margaret and Helen display a powerful attachment to the country in which they have their first encounter (while visiting Heidelberg) with the hard-headed and philistine Wilcoxes. The Wilcoxes see little in Heidelberg to charm them; the Schlegels see much. ‘The German is always on the look-out for beauty,’ Margaret Schlegel declares, defending herself as well as her paternal heritage. ‘He may miss it through stupidity, or misinterpret it, but he is always asking for beauty to enter his life.’8 Helen, revisiting the countryside around Nassenheide on Forster’s behalf, praises the landscape in words taken directly from the novelist’s own observations: ‘She spoke of the scenery, quiet, yet august; of the snow-clad fields, with their scampering herds of deer . . . [of] real mountains, with pine-forests, streams, and views complete.’9

It would be ambitious to read a direct comment upon the broadening rift between England and Germany into Forster’s famous words, spoken by Margaret Schlegel: ‘Only connect the prose and the passion . . . and human love will be seen at its highest. Live in fragments no longer.’10 It would be careless to dismiss the likelihood that Forster, writing a book about English and German attitudes at a time when war had become a looming probability, was making the case that he would argue more overtly in his political essays of the 1930s. Margaret’s statement can be read as a writer’s plea both for the thoughtful use of words (as opposed to the inflammatory language of the pre-war press) and for taking the larger view, for what Forster described in Howards End as ‘that interest in the universal which the average Teuton possesses and the average Englishman does not’.11

Howards End was published in 1910, the year that Henning von Arnim died, just one year after the sale of his beloved Nassenheide. The possibility of war hung like a cloud in the air; Elizabeth von Arnim, publishing a novel in 1909 about a German baron’s visit to England, had warned readers of The Caravaners that Prussian eyes were already sizing up their ‘plump little island’ and that the Prussian Junkers (‘that chivalrous, God-fearing, and well-born band that upholds the best traditions of the Fatherland’) had gathered in spirit, ‘like a protecting phalanx around our Emperor’s throne’.12

Protecting the Emperor from whom, precisely, von Arnim did not say. An assertion made elsewhere in The Caravaners that the Prussian eagle will always hold its place at the head of the European tree shows that England was not the only imagined aggressor. Encirclement, Germany’s fear of being trapped within a noose of unfriendly and allied powers, was much discussed in the circles in which the von Arnims moved.

Back in 1907, while paying one of her occasional visits to England, Elizabeth met up with another clever young novelist, Hugh Walpole. She invited him to take on the role that Forster had briefly occupied two years earlier, as an English tutor to her children. The meeting with Walpole took place over a lunch at a women’s club called the London Lyceum, the brainchild of a remarkable Birmingham-born woman called Constance Smedley who made a valuable contribution of her own to strengthening the Anglo-German connection.

Smedley was attending a conference in Berlin in 1901 when she noticed, with the disapproval of a staunch feminist, how many German women were still confined to the infamous triangle of the three Ks: Kinder, Küche, Kirche (Children, Kitchen, Church). Keen to help emancipate them from such a restrictive definition, Smedley shared her thoughts with Countess Harrach, an influential and progressive Palastdamen (lady-in-waiting) who divided her time between Berlin, her husband’s Silesian estate and her own family castle in Switzerland (Oberhofen). Together, the two women set to work.

The Berlin Lyceum opened its doors on 4 November 1905. The report in the Berliner Tageblatt of the following day mentioned only that the new club’s public spaces were gaily decorated; quite probably, the blueprint was taken from London, where Smedley offered thirty-five female members a library, an art gallery, a once-a-month book-club dinner and a monthly concert of modern music. Countess Harrach had prevailed upon the usually stodgy Empress Dona to support the project, with the result that the opening night included a large delegation from the court. The recently bereaved English Ambassador, Frank Lascelles, brought along his sister, Lady Edward Cavendish; his American counterpart, the gloriously named Charlemagne Tower, came with his wife. Speeches (all of which were faithfully reported by the Tageblatt) included one in which Constance Smedley expressed her ardent hope that the new Lyceum might become ‘a bond of union between Germany and England’.

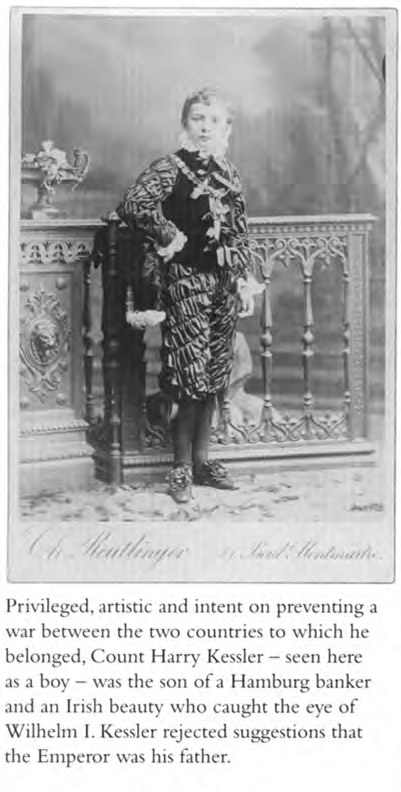

And so, working together with its London counterpart, it did. No insuperable divisions between the two countries existed in the shared world of culture, and it was from this deep mutual well that Smedley’s Lyceums drew their most valuable support. Max Liebermann, his nephew Walter Rathenau, the art patron and bibliophile Count Harry Kessler and the playwright Gerhart Hauptmann (an Anglophile who hungered for – and obtained – an Oxford doctorate to crown his German achievements) were recruited by Countess Harrach to assist and advise on the Lyceum in Berlin. In England, Smedley’s impressive committee included C. F. A. Voysey, Laurence Alma-Tadema, William Rothenstein, Frank Brangwyn, Sir John Lavery and Walter Crane. In Berlin, an exhibition of art by British Lyceum members went on show in 1905 before touring Germany. In London, at the suggestion of William Rothenstein, a corresponding show of works by twenty-five new German artists was organised under the aegis of the Lyceum in the winter of 1906 and displayed in a specially constructed hall at the (now entirely forgotten) Prince’s Gallery in South Kensington. From Berlin, the half-Irish Harry Kessler advised on which German artists should be included; the opening was followed by a slap-up banquet at the Savoy, attended by G. B. Shaw and presided over by that ardent Germanophile and most avuncular of political intellectuals Richard Haldane. Haldane’s younger sister, Elizabeth, the first translater of Hegel’s lectures into English in 1892, was also present.

Men like Harry Kessler and Richard Haldane were acutely conscious of the growing rift between their countries. They were not alone in their concern (Henry James was only half joking when he told an American friend in 1907 that he believed the Kaiser was training his cannons to fire on the chimney-pots of his own little Rye residence). An Anglo-German dinner held by Constance Smedley in December 1905 attracted a formidable list of guests which included the Earl and Countess of Aberdeen, the entire diplomatic staff of the German Embassy, the Lord Mayor of London and the editors of two of the more level-headed organs of British public opinion: George Prothero from the Quarterly Review and Austin Harrison from The Observer. Speeches, given by the German Ambassador, Count Metternich, by Prothero, Lord Aberdeen and Smedley herself, focused on the urgent need – in Prothero’s words – for those ‘who write, and who address great masses of persons, to do all they can to quench the flame of enmity’. Smedley herself pleaded that night for England to remember that Germany was not merely a commercial nation, but the land of art and literature, ‘of Beethoven and Bach, of Handel and Wagner, Strauss, Schubert, Schumann . . . That is the Germany we love . . .’13

Both the dinner and the speeches were reported upon the following day – and warmly commended – by the Daily Telegraph, the Morning Post and the Daily News. To the surprise of none, Smedley’s gallant endeavour at peacemaking passed without note from either The Times or the brand-new Daily Mail.

Of these two Germanophobic papers, Alfred Harmsworth’s venture, the Daily Mail, was the more active as a troublemaker. Erskine Childers, back in 1903, had written the widely read Riddle of the Sands, a naval thriller warning of danger from a foreign power. Struck by the magnitude of Childers’s success, Harmsworth commissioned a spine-chilling account of England under siege from the Huns.

The Invasion of 1910, published in 1906, was brashly advertised by the appearance in Oxford Street of a band of touts in Prussian uniforms, proclaiming evil tidings to the guileless shoppers. A German invasion was imminent! Details were available only in the Mail’s new giveaway book! Harmsworth’s idea was an instant hit. William Le Queux’s novel was translated into twenty-seven languages, including a pirated German version. Selling over a million copies, the book enriched the author and vastly increased the circulation of the Mail.

The Times, so sober in the appearance of its enormous, closely printed pages and small, sedate headings, was less cynical and –because of its august reputation – far more dangerous. The problem here was simply that the newspaper’s chief correspondent in Berlin, George Saunders, was fiercely anti-German (Houston Stewart Chamberlain, an English-born Anglophobe, later remarked that Saunders should have been hanged for the damage that he wreaked on Germany). Thanks entirely to Saunders, friendly opinions of the kind that were regularly expressed by such newspapers as the Anglophile Köln Zeitung never reached England. The Times, trusting in Saunders to tell the truth, actively contributed to England’s fears of a hostile, power-hungry empire on the make, building up its massive, armour-heavy navy not – as the German Emperor would always insist, to protect his Baltic coastline and provide a useful backup to Britain in the Far East – but for attack and destruction.

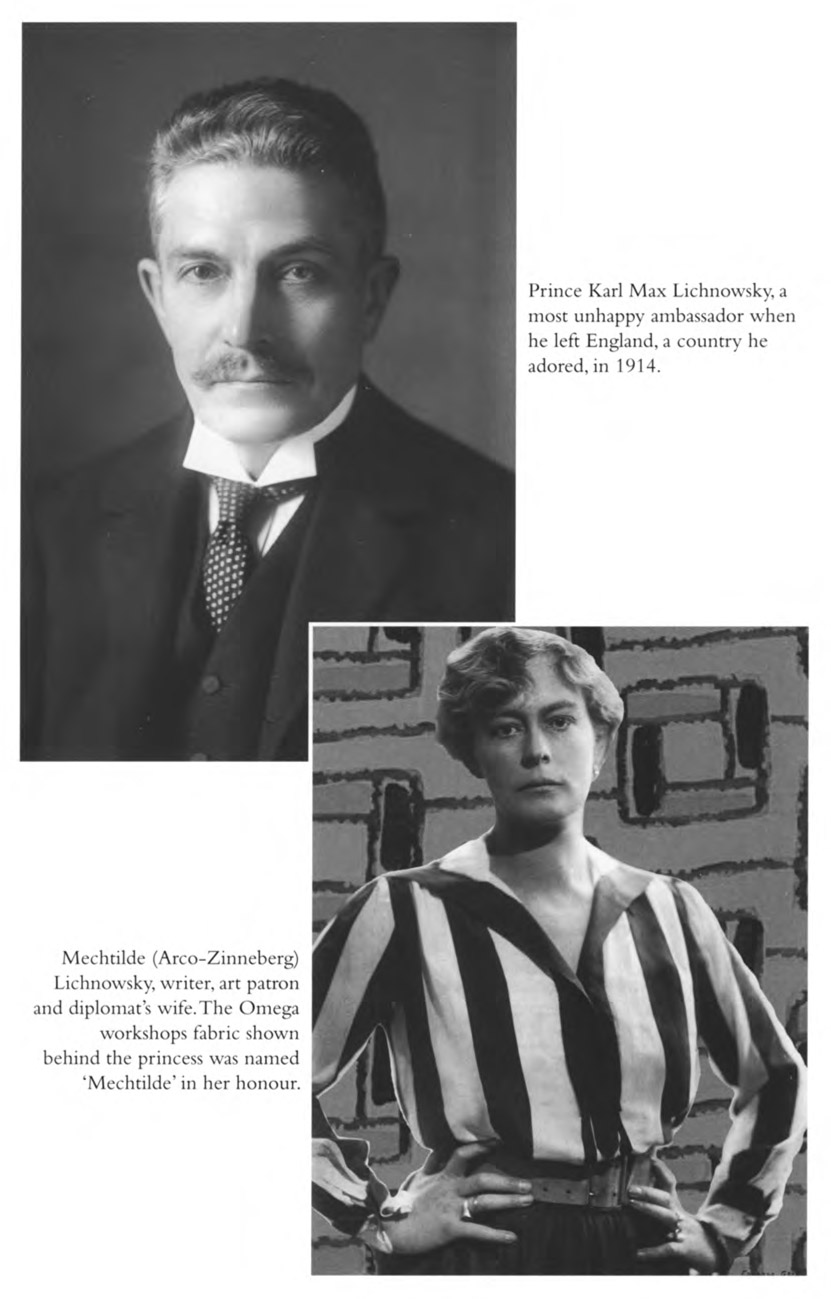

Fears were growing. Daisy Pless, taking charge of all social arrangements at the German Embassy in London during the residence there of the deaf, shy and quietly appreciative Count Metternich, had noted in her diary for 23 April 1905 that the English kept asking her whether the Germans hated them, or their country, or both.14 Cecil Spring-Rice, following what amounted almost to a diplomatic incident during that same year – the Emperor, sulking because Uncle Bertie had sent his son, the Prince of Wales, over to visit Berlin in his place, had forbidden his own eldest son to visit the King at Windsor – told the American President’s wife that ‘the indications are most threatening’.15 Hermann Muthesius, lecturing on the glories of the Glasgow School in Berlin in 1907, was so outraged by a command to stop praising British art that he withdrew from the association that had rebuked him and joined, instead, the group that subsequently formed the state-sponsored Deutscher Werkbund and that included Peter Behrens, Mies van der Rohe, Richard Riemerschmid and Henry van de Velde.

Daisy Pless, who knew the rulers of both countries well enough to have persuaded them to stand as joint godparents to her eldest boy, Hansel, exerted all of her considerable personal charm in the endeavour to reconcile volatile Wilhelm with his royal uncle. Harry Kessler took a more radical approach. He launched a public appeal.

The son of a rich Hamburg banker and a beautiful Irishwoman, Alice Blosse Lynch, the dapper, diminutive and passionately artistic Kessler stood in a perfect strategic position to create a bridge between the countries. Educated in England and France, he went on to university in Germany, studied art history and – at the age of twenty-four – undertook a lecture tour of America. In England, where he formed strong links with the art world through William Morris, Augustus John and the Rothensteins, he took time off, in 1902, from studying typefaces at the British Museum to attend both boxing matches in the East End with his friend Aristide Maillol and theatres in the Haymarket. Impressed by the dramatic setting of a play – it was Ibsen’s The Vikings – directed, in 1903, by the startlingly handsome Edward Gordon Craig, Kessler invited Craig to work, at Weimar, with Hugo von Hofmannsthal (a disaster) and then with Max Reinhardt (another disaster).

The friendship between the two men survived such disappointments, finding its fullest artistic realisation in Craig’s illustrations for an edition of Hamlet printed by Kessler’s Cranach Press. That commission did not come until 1913; back in 1905, Kessler’s attention was focused on destroying the vitriolic influence of another form of press: the anti-German British newspapers represented by The Times and the Daily Mail.

On 5 January 1906, a remarkable document appeared in the Letters columns of The Times. It was a plea for peace; a reminder that – in Kessler’s own words – ‘A war between the two powers would be a world calamity for which no victory could compensate either nation.’ Its request, directed at the very paper in which it appeared, was that The Times should desist from ‘attributing to Germany sinister designs against England, and thus sowing sentiments that in an emergency would render difficult and perhaps impossible the task for those responsible for the peace between both countries’.

The message was clear. A list of signatories from Germany included Richard Strauss, Max Liebermann, Ernst Haeckel, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche and Siegfried Wagner, while the English side was represented by Thomas Hardy, Jane Morris, John Lavery, Walter Crane, Edward Elgar, Gilbert Murray, C. H. Shannon and Isaac Zangwill. Harry Kessler’s staunchest ally, the Bradford-born (to German parents) artist William Rothenstein, was among the first to sign his name.

In the short term, Kessler’s appeal proved effective. On 8 January 1906, just three days after the letter’s publication, The Times informed its readers of an assembly of several thousand peace-seekers in Munich, headed by the British Minister in Residence, Sir Reginald Tower, and Munich’s Mayor, Herr von Borscht. The purpose of this gathering, so The Times reported with uncharacteristic cordiality, was to demonstrate a wish for ‘friendly relations’.

The new mood was short-lived. At the end of the month, the royal launching of Britain’s first and massively expensive Dreadnought battleship prompted the tiresome question of cost and justification. The Times was ready to help out. The German Emperor’s recent birthday was alleged to have been celebrated by speeches which – according to the Germanophobic George Saunders – had adopted a stridently military tone and had been received with cheers. Anti-German feelings in England, The Times rumbled, were now running very high indeed.

The commissioning of the Dreadnought had been sparked off by a brief summer visit that King Edward paid to his nephew at Kiel in 1904. Daisy Pless was present, observing the ceremonies from the comfort of the Vanderbilts’ yacht. (American yachtsmen were regular visitors to the Emperor’s favourite harbour, where they annually defeated him in the battle of the waves.) The Princess took the view that the King’s visit, however small a gesture, demonstrated good diplomacy. Uncle Bertie had been at his most affable, offering nothing but admiration as Willy showed off the results of his shipbuilding programme. (The four funnels of the gigantic Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse are just visible in paintings of the occasion.) Taking his departure, the King of England was all smiles. By the end of that year, however, word reached Berlin that Britain’s new First Sea Lord, Sir John Fisher (a man for whom the sea-loving Emperor professed great respect) was overseeing the construction of a ship intended to dwarf and intimidate all rivals. The Dreadnought, built in secrecy, was launched into the English Channel in 1906. Its appearance marked a new and worrying stage in the battle of the big ships, and an increasing chill between the kingly and the imperial courts.

On a domestic scale, the Emperor decided to treat Britain’s new war-craft as a joke. ‘Our British dreadnought’ was the name Willy playfully bestowed upon Ethel Topham, the governess appointed to teach English to his daughter Viktoria Luise and his son Joachim.

Miss Topham (whose charges already spoke better English than her German) waited until 1926 to publish her recollections of life at the Prussian court. Her account throws fascinating sidelights upon one of the most unfortunate episodes in the pre-war history of Anglo-German relations.

Edward VII, following his 1904 expedition to Kiel, waited three years to offer Wilhelm the further olive branch of the first family visit to Windsor since Victoria’s death. Reluctantly undertaken in November 1907, when the Emperor was suffering from one of his unpredictable fits of Anglophobia, the excursion proved a huge success. The Empress Dona, who did not like England, was won over by a Christmas shopping tour of Harrods in the affable – and hugely pro-German – company of Richard Haldane. The crowds showed their usual appreciation of the Emperor’s delight in donning English uniforms for every possible occasion. Wilhelm, to the relief of all, was on his best form. While Dona and their accompanying suite returned to Berlin, Wilhelm, concerned about a polyp in his throat, decided to take a private rest-cure at Highcliffe, a Hampshire castle (with a view towards Cowes) owned by Colonel Edward Stuart-Wortley.

It seems to have been by mere coincidence that Highcliffe was owned by a cousin, through marriage, of a man whom the Emperor had begun to venerate as the voice of truth: Houston Stewart Chamberlain. Stewart Chamberlain’s particular skill, odiously apparent in his grovelling letters to the Emperor, was to combine gobbets of handy erudition with deferential tributes to Willy’s genius and majesty. Colonel Edward Stuart-Wortley was less complex. Eager to do his bit towards improving England’s relations with Germany, he asked only the honour of being permitted to remain on hand. The sole condition that Stuart-Wortley requested to be imposed during Wilhelm’s visit to Highcliffe was that the Emperor would permit him to listen and, perhaps, to advise.

Wilhelm’s mood swings were always extreme; playing the bluff English gentleman of leisure for his host at Highcliffe Castle, he grew ecstatic. Everything delighted him: the pretty manners of the castle’s estate children; the beauty of the unspoiled coastal landscape; the decorous habits of an old-fashioned household; the nonchalant sportsmanship, even, of a local clergyman who boxed as well as he played cricket.

Back in Berlin, Dona read Willy’s joyful letters aloud, compelling her court ladies to hear about that ‘indefinable something which English homes alone possess of comfort’. Feelings about the Emperor’s disloyalty took the form of cross looks cast at poor, English-born Miss Topham, or small, ironic bows.16 Discomfited, Miss Topham nevertheless glowed with pride: these letters, she believed, offered proof of ‘how intensely he [the Emperor] loves and admires English life as apart from English politics’.17

The Highcliffe interlude prefaced a disaster that almost led to Wilhelm’s abdication. Colonel Stuart-Wortley, having paid a return visit to Germany the following summer as the Emperor’s guest at Metz, wrote an article of which an advance précis went to Berlin. It was seen both by the Emperor and his chancellor, Count von Bülow. No revisions were made.

On 28 October 1908, the ‘Highcliffe’ article appeared in the Daily Telegraph. It quoted Wilhelm as having described the English as ‘mad, mad, mad as March hares’ and of presenting himself as the man of peace who struggled to defend an ungrateful little Britain from the wrath of the great Fatherland. (‘The prevailing sentiment among large sections of the middle and lower classes of my own people is not friendly to England,’ Wilhelm had allegedly declared to his English host.)

English readers reacted with mild amusement to the Emperor’s airs; the Germans were outraged. A further scandal erupted. News of the sudden death – while prancing about in a pink tutu – of one of Wilhelm’s generals (the Emperor had been an enthusiastic observer of the performance) broke together with the first revelations of homosexuality in the circle of men who habitually addressed the Emperor as ‘Liebchen’ (‘Darling’). Abdication was discussed. Miss Topham, attending silent lunches under the rococo garlands and naked deities of the Apollo Room, noted that the Emperor looked pale and crushed and that his wife was always in tears.

Chancellor Bülow, forced to shoulder the blame for the Telegraph article, was sacked and replaced by the tall, scholarly, musical and eminently trustworthy Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg.

Harry Kessler’s 1906 appeal for peace had produced no lasting results; the shipbuilding race was underway; talk about the inevitability of war had become commonplace. The Highcliffe interview added the frosting to a relationship that was already turning glacial.

In February 1909, the ailing British King decided to contribute what he could towards alleviating the situation. A show of family unity was required; an act of homage to the Emperor’s court would be an act of good diplomacy.

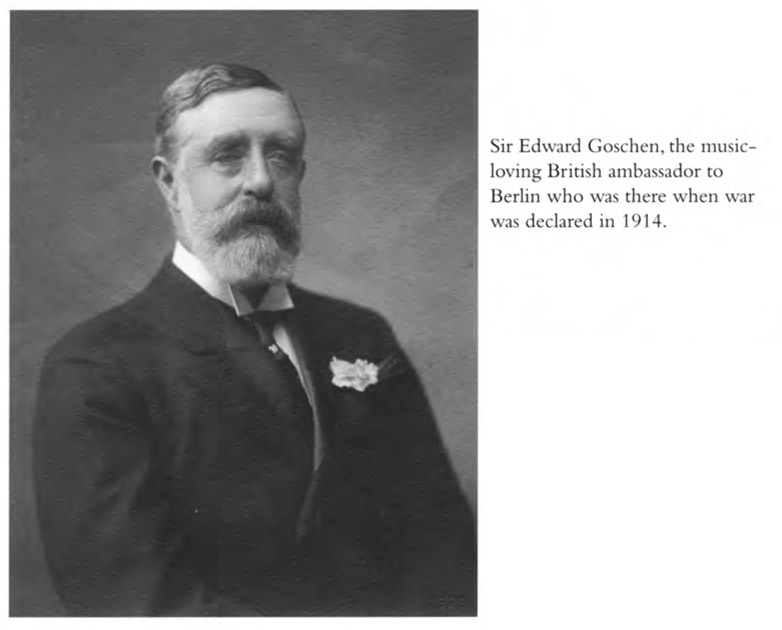

Edward’s 1909 visit to Berlin was undermined by illness and mishaps that started at the station when the royal train steamed to a halt at the wrong platform and Wilhelm, grandly waiting to receive his guest at the far end of a long red carpet, had to run like a hare to catch up. Escorted to the finest of Willy’s royal carriages, the British King and Queen were forced to get out and walk to the palace after two of the elegantly caparisoned coach horses went on strike. A frightening collapse by the King during lunch at the Embassy (‘We all thought it was the end,’ Sir Edward Goschen’s private secretary, Benjie Bruce, confided to his diary) was followed later that day by an even more worrying moment. Miss Topham, who was present at the ballet performance of Sardanapalus (forming the first part of an interminable evening), noticed that King Edward, jolted from slumber by bangs and flashes of light from the stage, evidently thought the opera house was on fire. He looked, the governess thought, both panic-stricken and ill. Back at the palace and settling down for a cosy gossip with Daisy Pless, Edward suffered a second seizure. His eyes stared, his breath came in short gasps, the cigar fell, unlit, from his fingers to the floor.18 A philandering man might suffer a worse fate than to expire in the arms of Daisy Pless, but Daisy was not the only one who blanched at the unimaginable consequences if the King of England dropped dead during a state visit to Berlin.

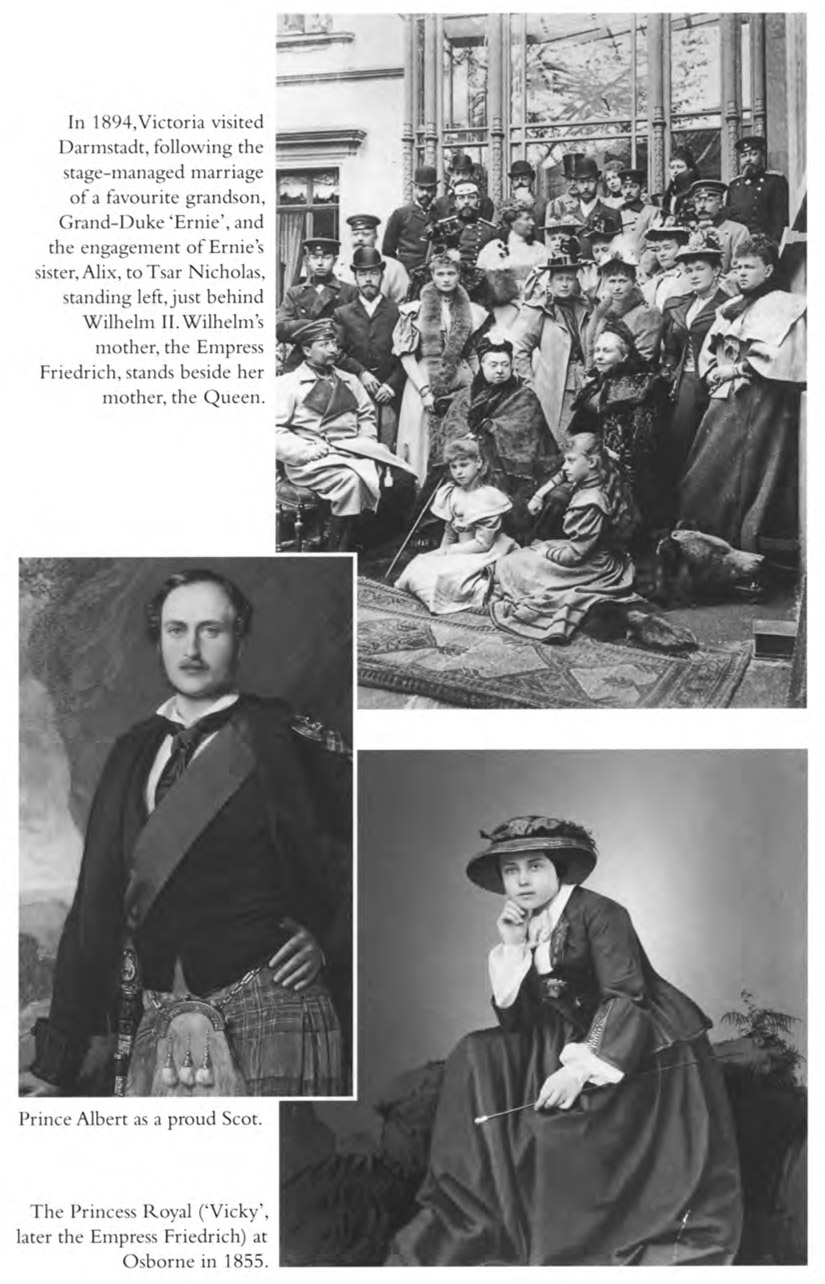

Death held off until the following year when Edward VII, aged only sixty-eight, was struck down by a series of heart attacks. Wilhelm, invited to stay at Buckingham Palace by the widowed Queen, was charmed by Alex’s friendly manner, and impressed by the dignity and evident sadness of the quiet crowds who turned out to line the streets for the ceremonial procession.

Competition for attention was now stiffer than it had been in 1902. Wilhelm’s ranking as a mere nephew impressed reporters less than his role, back then, as Queen Victoria’s eldest grandchild. Faced by the hooded camera, and flanked by seven competing monarchs (most of them rather younger than himself), Wilhelm still managed to seize the position directly behind the new King, allowing him to conceal his left arm from view, while gazing out over George V’s head with an air of quiet authority.

On film, if not in life, the Emperor would present (to the eyes of a hopeful Germany) her place as the friendly power behind – but never against – the English throne.