It was inevitable that love would play a role in the lives of some of Germany’s impressionable young visitors – and that it would be tested when love could come to appear as an act of support to an abhorrent regime.

For the powerful and ambitious mother of Dick Seaman, one of Britain’s finest young inter-war racing drivers, the news that her son intended to marry Erica Popp, the glamorous German daughter of the Nazi manager of BMW, came as a galling surprise.

Born into great wealth in the England of 1916, Seaman had been recruited to join the Mercedes team in 1936, following his outstanding victory that year on the celebrated course at Donington Park. (In the motor world, it was the big race at Donington the following year that would send out the signal, through the victory of Bernd Rosemeyer in an Auto-Union machine, of how thoroughly Germany was outstripping the technology of her European neighbours.)

Not everybody relished Seaman’s defection to the German Mercedes team (his recently widowed mother had hidden their original telegram of invitation to her son) or the fact that, winning his first major victory for his adopted country in 1938, the British driver offered two Heil Hitler salutes from the podium. Lauded to the skies in Germany, where the girls from his local village garlanded the handsome young Englishman with wreaths of oak leaves and the German press paid tribute to his nerveless driving, Seaman’s engagement to Erica Popp crowned his commitment to a nation to the regime of which his own mother remained fiercely opposed. When Seaman rashly wrote home to praise Hitler’s efficiency in dealing with any form of opposition, Lillian Seaman responded with a withering tribute to the fine handling of the helpless and the weak by that same Führer whom he so admired.

Mrs Seaman relented enough to attend her son’s marriage when it took place in December 1938, at Caxton Hall. Nevertheless, her disapproval had sown a seed of doubt. Five months later, Seaman asked his fellow racing driver Earl Howe about the possibility of coming home to England. Howe, responding on 5 May 1939, was against any such idea: ‘stick with it . . . far better retain every individual contact with Germany in every shape and form’.1

The following month, while driving a Mercedes Silver Arrow at the Belgian Grand Prix in heavy rain, Dick Seaman crashed into a tree when he skidded on a sharp corner. Trapped in his blazing car, he was finally rescued and rushed to hospital, suffering from severe burns. Rather nobly, Seaman still managed to take full responsibility for the accident, apologising to his German manager for having let the team down. He died shortly afterwards. In Germany, Hitler sent a large personal wreath to the funeral. In England, the Daily Telegraph accorded just two short paragraphs to one of the finest British drivers of his era. Seaman was only 26. Mercedes still, to this day, take care of their English driver’s grave in Putney Vale.

Delphine Reynolds was a characterful young woman (one portrait represents her grasping a whip) who had been given a part of Croydon Airport in 1928, along with a Gypsy Moth biplane. Delphine, who took an airship tour over the site of the 1936 Olympic Games with the son of the celebrated Count Zeppelin, had been cutting her annual swathe through the susceptible schloss owners of Bavaria in the summer of 1939 when, back from frolicking around the glorious Czechoslovakian home of Count Kinsky, she was spotted by the British Ambassador tripping onto the floor at a ball in Berlin. The gala event was being held during the last torrid week of August; Nevile Henderson, taking the exuberant Delphine aside, brusquely ordered Miss Reynolds to pack her bags and take the next train back to England.2

Henderson’s orders came just in time to prevent Delphine from joining the contingent of English women who, by virtue of their marriages to Germans, or ill-timed tourist visits, would find themselves living in a state of virtual imprisonment for the duration of the war.

Lady Camilla Acheson, the nineteen-year-old daughter of an Irish earl, had received a European education that culminated with six months at Neue Bern, a school run by a German aristocrat at her Bavarian family home. Staying at the schloss, and lending its owners a helping hand through the summer term of 1936, was a handsome former pupil, Christoph von Stauffenberg. Cast as Celia in a summer production of As You Like It, pretty Camilla found herself acting opposite Christoph’s Oliver de Bois – and fell in love. Her mother, concerned by the fact that the dashing Stauffenberg was six years older than Camilla, a German and – graver still – a Catholic, promptly flew out to Munich and delighted Camilla’s impoverished hostess by renting out half of the schloss while she took stock of the suitor. Apparently, Christoph passed muster. The couple were married, back in London, at Brompton Oratory, in 1937. By 1939, however, they had returned to Germany. Camilla, following the outbreak of war, found herself in the unhappy situation of Daisy Pless, back in 1914: a German’s wife, she had become an enemy alien, trapped in a foreign land, and allowed no contact with her anxious British family.

Christoph von Stauffenberg, no fan of the Nazi regime, looked for work that would allow him to pass as a good German citizen without having to kill Camilla’s countrymen. He signed up, but only as a reader of the English newspapers for the supposedly useful military information that – as Stauffenberg was cynically aware – would never appear in print.3 Camilla, meanwhile, was able to learn of all the news at home, while escaping the very real risk of being treated as a spy. To read English newspapers in wartime Germany without specific permission was an act of treason, even for a foreign subject.

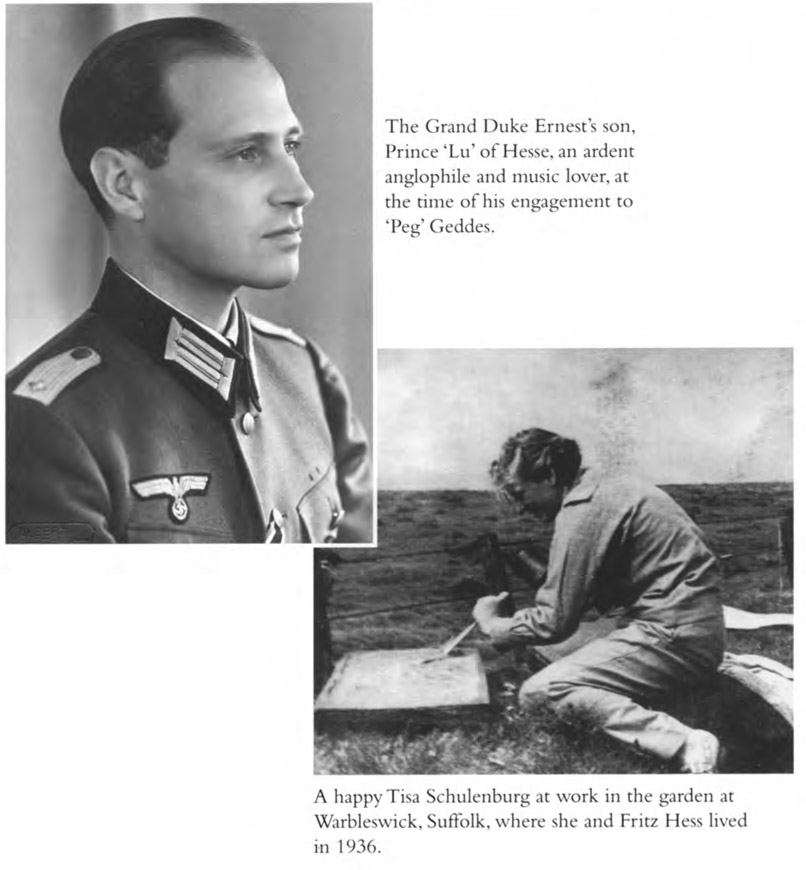

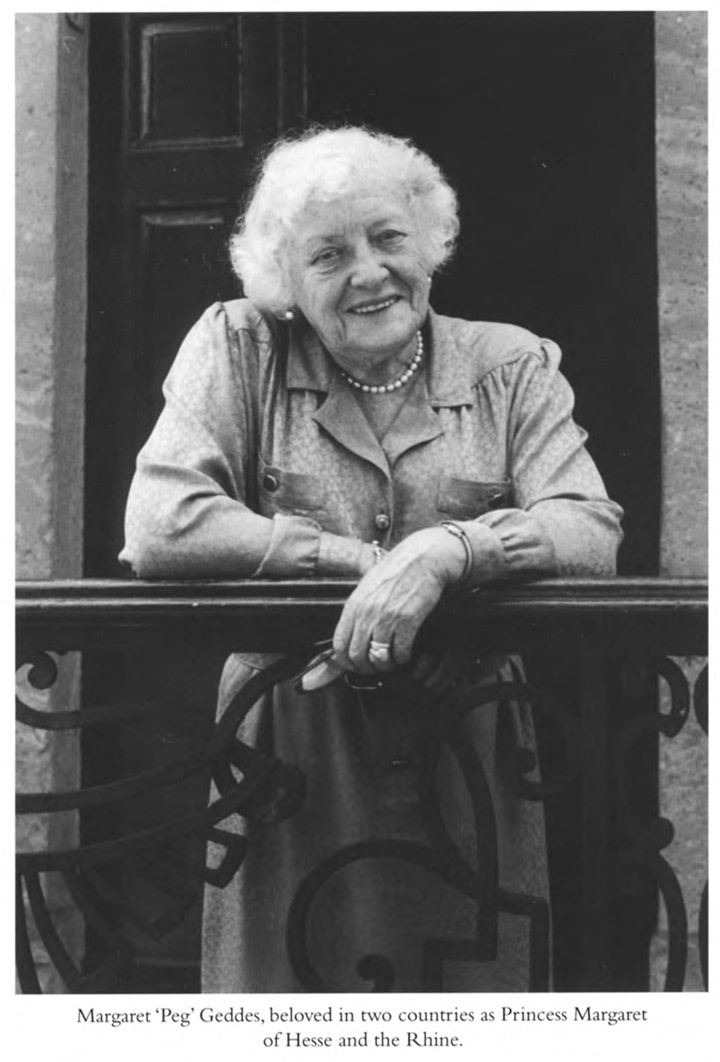

Margaret Geddes, a young Scotswoman who was known to one and all as ‘Peg’, travelled out to Germany towards the end of 1935 in order to join two beloved brothers at a pension in Bavaria. Unknown to Peg, a little advance plotting had been going on. Waiting to meet her at the local station in the place of her brothers and all ready to conduct her to Haus Hirth was a dark-haired and extremely good-looking young German. His name was Ludwig (‘Lu’) and he was the music-loving second son of Grand Duke Ernst of Hessen-Darmstadt.

The Grand Duke’s connection to Haus Hirth went back a long way. Georg Hirth, whose widow, Johanna, now ran the pension adjacent to their family home at Grainau, was the publisher of Jugend, the influential magazine from which the Jugendstil movement took its name. Grand Duke Ernst had been Jugend’s chief sponsor and his family had remained close to Hirth’s widow. (George Donatus, Lu’s older brother, married to Princess Cecile of Greece, had just chosen the name Johanna for their newborn daughter.)

A cheerful, high-spirited and openhearted young woman, Margaret Geddes found herself instantly at home in the carefree atmosphere of a timber-framed house filled with art treasures and mementoes of earlier guests. Rex Whistler had stayed there with the Sitwells and William Walton; Johanna Hirth also spoke warmly of Helen Keller, whose discreet and sometimes lengthy visits to Haus Hirth were never mentioned in Keller’s published work.

While Peg’s younger brother, David, went off on cultural trips around the Bavarian towns with the prank-loving young Nazi owner of a beautiful nearby castle, Peg spent most of her time with Lu. The result, since Prince Ludwig came from a family who had always used English as their preferred language, was that Peg’s German grammar progressed less well than did her romance with a kind, sensitive and humorous young man.4

Prince Ludwig had already spent a short time working as a junior official at the Büro Ribbentrop in Berlin. Seeking reasons to be near his beloved Peg, he arrived in London in October 1936 as one of the young attachés who were meant to help smooth the path of his former boss, a somewhat gauche new envoy to the Court of St James’s. Lodged in an annex to the Embassy in Carlton House Terrace, Lu, Baron Dörnberg, Erich Kordt and Reinhard Spitzy were offered a first-hand view of a revamp to the old de Bunsen home that included marble cladding throughout, the installation of eighty-two telephones and the relegation of all domestic staff to the basement. The Ribbentrops, meanwhile, finding the noise of marble-cutting got on their nerves, decamped to a smart Eaton Square apartment that had been loaned to them by Neville Chamberlain.*

The stories of social ineptitude displayed during the brief sojourn in London of ‘Herr Brickendrop’ (Maurice Baring’s nickname for the hapless Ambassador) are legion. Most focus upon Ribbentrop’s compliance with Hitler’s firm instructions to deliver the Nazi salute upon all occasions, whether standing in Durham Cathedral as the guest of the astonished Londonderrys, or while offering his formal respects to England’s new king, George VI. Reinhard Spitzy’s memoirs describe how the young German attachés collapsed in giggles during the heil that was delivered at Buckingham Palace; Ribbentrop, a man who craved social acceptance and now found himself mocked, grew ashamed and sullen. Taking refuge in prolonged baths and capricious departures to the cinema when he was meant to be attending semi-official dinners, he became – which was unfortunate in an ambassador – increasingly hostile to the English hosts whose occasional inquiries about his past life as a wine merchant (Ribbentrop had married a Champagne heiress in 1920 and worked for her family company while purchasing a ‘von’ title to improve his status) did nothing to improve relations.

Lavish financial support from Berlin provided a degree of compensation. Nobody in the German government had been especially pleased, in the bright summer of 1937, when George VI was crowned king, following the abdication of his older – and very pro-German – brother Edward. Reinhard Spitzy gazed down from the front windows of the Embassy upon the regal celebrations in the Mall: ‘a sea of colours, gold, magnificence and splendour’. But only Ribbentrop could boast that he had managed to charter a private plane from Berlin to bring over a cargo consisting entirely of Champagne and caviare.5

Sir Auckland Geddes – belonging to the generation of those who lost close family in the war – had begun as a stern opponent of his only daughter’s alliance to a Hun. Lu’s considerable charm and Peg’s evident happiness combined to prevail; in the summer of 1937, Geddes gave the alliance his grudging consent. Plans for an October wedding were deferred, but only out of respect for the death that month of Prince Lu’s father, the old Grand Duke. (Buried out at Wolfsgarten beside the grave of his beloved first child, Elizabeth, Hessen-Darmstadt’s gentle ruler would have been less happy with Hitler’s command that his coffin should be carried through Darmstadt by a phalanx of steel-helmeted soldiers.) The London ceremony was hastily rescheduled for 20 November; Peg, still enchanted by her memories of Haus Hirth, made plans to wear a traditional wedding costume from Bavaria.

The Prince’s forthcoming marriage to a woman of British birth was cause for rejoicing in a family that took pride in its close connection to Queen Victoria. Plans were made for Lu’s widowed mother and his brother’s whole family to come across to London four days before the ceremony. All was carefully arranged: Eleonore (the widowed Grand Duchess) was to stay with her late husband’s sister, Victoria Milford Haven, while George Donatus and his family lodged with the Mountbattens on Park Lane. All promised to be both very grand and very cosy.

On 16 November, having been driven down to Croydon Airport by the chauffeur of a solicitous Lord Mountbatten, Lu and Peg started to scan grey skies for a Sabena, scheduled to be coming in soon from Belgium. Bad weather, apparently, had caused a delay. A few minutes later, the manager of Imperial Airways brought them devastating news. Attempting to make a stopover on the flight from Belgium, the royal pilot had struggled to land his craft in dense fog. A wingtip had nicked the edge of a tall factory chimney. Tipped, crashing against the structure, the plane went down in flames. Lu, transformed within a few stark seconds into the new Grand Duke of Hessen-Darmstadt, had lost his entire family, including the eight-month unborn baby of his beloved sister-in-law, Cecile. Only little Johanna had escaped, having been left behind with her nurse because she was considered too young to take along. Lu and Peg found one grain of comfort in taking an instantaneous decision to bring up Johanna as their own beloved daughter.

The wedding was immediately brought forward. Dressed in deep mourning, the desolate young couple were married at daybreak on the day after the crash, enabling them to fly straight out to Darmstadt for a mass funeral. Lu – thin, forlorn and white as a ghost in his new role as head of the family – led the sad procession through the streets. Following him (the only other male member of the family to wear a plain black coat instead of a Nazi uniform) was Cecile’s young brother: Prince Philip of Greece, England’s future Duke of Edinburgh.

Settling into their new life as the rulers of Hessen-Darmstadt, Lu and Peg suffered an additional blow in 1939, when Johanna, their adopted child, died after contracting meningitis. Although devoted to young people, the couple never had children of their own.

Shiela Grant Duff would end by marrying Michael Sokolov, one of Nikolaus Pevsner’s fellow lodgers at Francesca Wilson’s Birmingham refuge for exiles. But Shiela became far better known for an intense friendship – it began at Oxford in 1931 – that she formed with Adam von Trott.

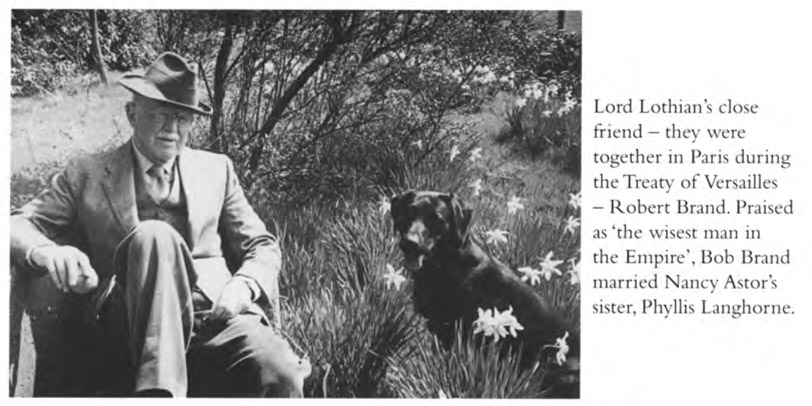

Born in 1913, Shiela was only a year old when her father died leading his British regiment into battle in the war during which two of her uncles were also killed. Brought up, not surprisingly, to view war as the greatest of evils, Shiela reached Oxford at the time when the mood of the university favoured peace and reconciliation. The German Rhodes Scholarships, brought to a halt in 1914, had just been reinstated. Philip Lothian, as secretary of the Rhodes Committee since 1925, had pushed hard for their restoration; Albrecht von Bernstorff – enormous, jovial and well loved in both countries – acted as the principal advisor, having himself been a pre-war scholar.

Among the first candidates that Bernstorff picked out was a young aristocrat who had already experienced a little of Oxford life, having taken a term out from his studies at Göttingen in 1929 and fallen in love with England, the country of which he had been hearing all his life. His full name was Adam von Trott zu Solz and he came from a part of Germany so steeped in connections to his own family that the woods around the family home (Imshausen) where he had lived since 1919 – Adam was born in Potsdam – were known as the Trottenwald.

Reading between the lines of their published letters, and of Grant Duff’s memoirs, it’s fair to surmise that Shiela at some point did have a love affair with von Trott. Certainly, Adam proposed to her (she turned him down) during the mid-thirties. At the time when they met at Oxford, however, von Trott was involved in a relationship with Diana Hubback, one of Shiela’s girlfriends from St Paul’s, while Shiela herself had fallen for a brilliant young Marxist, Goronwy Rees. All of this youthful Oxford set, back in those ardent college years, were passionately idealistic and firmly committed to the left.*

Von Trott’s astonishing good looks and romantic manner would become legendary among those who knew him during his Oxford days. Tall, lean and dark-haired, with a full mouth, high cheekbones and deep-set violet eyes, he owed his near perfect English both to an English nurse and to an American grandmother proudly descended from John Jay, one of her nation’s founding fathers. An almost mystical attachment to his German homeland – and especially to the countryside in which he grew up – added to the attraction of a young man who seemed both familiar and foreign in his combination of blithe playfulness and grave intensity. At Balliol, he was instantly surrounded by a group of Oxford admirers. Leslie Rowse (a friend from Adam’s first visit to England) was a clever young Cornish lecturer at Merton College who travelled with Adam to Berlin and was thrilled to be taken on a tour of the former Kaiser’s home. Maurice Bowra, a discreet but regular visitor to Germany throughout the 1930s, shared Rowse’s snobbish relish for Adam’s illustrious ancestry. Closer by far was David Astor, a shy and thoughtful student whose family home at Cliveden and friendship with Philip Lothian would later offer Adam an inside track for his urgent political mission. Astor’s loyalty to his friend never faltered, even in the darkest of times.

Shiela’s published account of the impact that Adam von Trott made upon her was written many years later. ‘He was the first German I ever met,’ she wrote in 1982, ‘and for me he personified all the tragic implications of a “fratricidal war”, which was how more and more people were describing the war of 1914–1918.’6

Close friends during their Oxford years, Shiela and Adam stayed in touch by letters during the period when Adam returned to – and rashly attempted to defend – the newly Nazified Germany that had emerged during his last year at Balliol. In February 1934, working in Breslau and stung by the British accusations of ethnic persecution that had been lodged against Germany (if only in a small section of the English press), von Trott went on the attack. In a letter addressed to the perceived culprit, the Manchester Guardian, he denied the mistreatment of Jews in his own part of Germany, while claiming that the only people to be held in camps were dangerous dissidents. Such misstatements, when combined with his truculent tone, did Adam great harm in English political circles and lost him many potential supporters. Shiela, while disconcerted by a public letter that sounded so unlike the friend she had known and loved, was nevertheless persuaded to put dismay aside and visit Adam during that summer, at his home in Hessen-Kassel.

That first visit to Imshausen, while it helped Shiela to understand how Adam could abhor the Nazis and yet love Germany, was not a total success. A fierce political quarrel that broke out between Shiela and Adam’s strong-willed mother was patched up with difficulty. A pledge, however, was touchingly sworn between the two young people that their own Anglo-German friendship, their ‘alliance’, should continue to stand as a symbol for what might be achieved by their two countries.

Shiela returned to England filled with doubts. Adam, however, felt that he and his cherished English friend had been drawn closer by her evident delight in the landscape he adored. In correspondence with Shiela that autumn, he wrote like a lover about the strange, charmed feeling that had come over him as he recalled the scenes that he had shared with her. He wrote about the sound of village girls and boys singing their songs in the valley behind him as he strolled alone between wooded hills, ‘a tinge of autumn over the crowns and a blue haze joining them to the pale night sky’. The meadows and hedges had turned silver in the pale moonlight, ‘and it was so reassuring to walk quietly on the gravel of the white road with all the apple trees on either side . . .’7 A little mischievously, in another letter, Adam mentioned that he had been reading Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and had thought that he would not mind playing the lusty role of Mellors, identified as ‘the forester’.

In her memoirs, Shiela insists upon the unfailing love she felt in 1934 for Goronwy Rees, a shocked witness of violent scenes taking place in Berlin during the June massacres in Munich. But it’s hard to dismiss the glints of an emotional undercurrent swirling through the letters that passed between Shiela and Adam. An impressionable young woman may have loved more than a single, idealistic young man during those dramatic times.

In 1935, Shiela paid a second visit to Adam’s home. By then, however, she had come under the influence of a fiercely anti-Nazi American journalist. Edgar Ansel Mowrer, having made a noble and unusual deal with the German authorities to quit his Berlin news post in exchange for their release of an imprisoned Jew, was continuing to savage the Third Reich from Paris, as bureau chief to the Chicago Daily News. (America’s reports of events in Germany were less censored than those that – occasionally – made it into the British press.)

Working alongside Mowrer in 1934, Shiela was teased for acting (in her own phrase) like ‘Hitler’s girlfriend’. Slowly, she began to question the views not only of Adam, but of the whole crowd of her appeasement-minded friends at Oxford. At the beginning of 1935, she was despatched by the venerable editor of the Sunday Observer, J. L. Garvin, to report upon the real feelings of inhabitants of the coal-rich Saar about their chance to be governed by the Nazis. As with Wystan Auden’s observations at the time of Hitler’s election to the presidency, what Shiela observed was a coerced response to a supposedly free plebiscite, with a beaming pink-and-white Hitler prancing in on 1 March to claim his victorious role as the chosen one. The Saarlanders, in Shiela Grant Duff’s indignant view, had been allowed no choice at all.* Was a country governed by such methods really worthy of Adam’s passion?

In 1936, a far-sighted Garvin despatched his enthusiastic female reporter to Prague. Shiela, to her amazement, found herself to be the only British journalist in a captivating city that felt like the gentle hub of an earlier world: an un-Nazified, civilized Europe: ‘. . . no rioting, no vandalism, no terrorism, no pornography’.8

Travelling out to Czechoslovakia, Shiela had stopped, once again, to pay a visit to Adam von Trott. Their friendship, once so strong, had already begun to weaken. Adam had become closely attached to a fellow lawyer, Peter Bielenberg, and his Irish-born, English-educated wife, Christabel Burton, a niece of Lord Rothermere. But, while the Bielenbergs resolutely avoided joining the Nazis, Adam believed that opposition in Germany could only effectively be launched from a position within the Nazi party itself. Shiela, unable to accept the idea of a Nazi resister, understood only that her friend planned to join an abhorrent regime. Adam defended his attitude. He tried, so Shiela later wrote, ‘to make me understand the position of one who both loved and hated what he belonged to’. It was a contradiction that rang false with a woman of unsubtle beliefs. To Shiela, there was simply a right and a wrong. ‘He had noble ambitions,’ she conceded, ‘but his roots were deep in the earth of Germany.’9

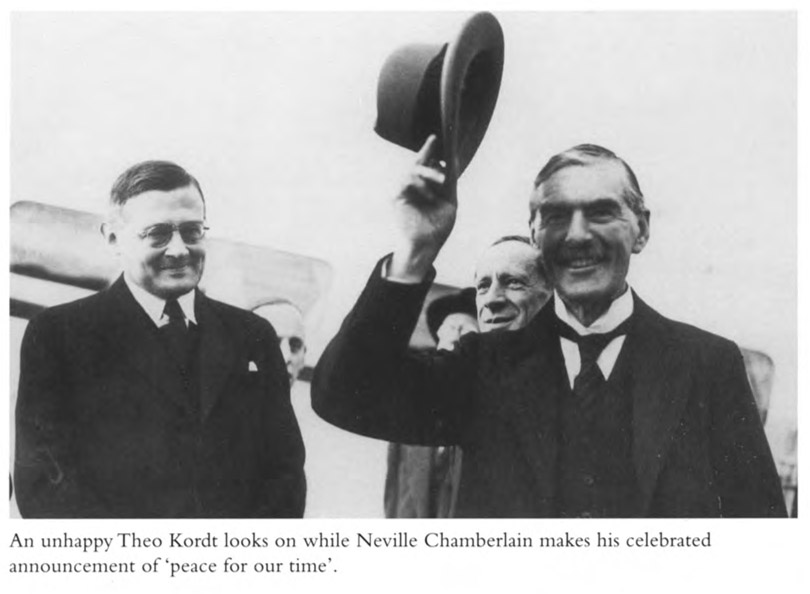

Shiela Grant Duff’s first-hand observations in Prague of the increasingly tense situation in Czechoslovakia, as Germany turned its focus relentlessly towards the east, found powerful expression in her Europe and the Czechs. The book came out, with extraordinary timing, in 1938, published on the very day that Neville Chamberlain flew home from Munich, brandishing his proclamation of a purchased peace. At a time when almost nothing had been written about modern Czechoslovakia (the absence of any British journalists in Prague during Shiela’s time there highlights England’s utter indifference to Germany’s eastern expansion plans), Europe and the Czechs became key reading in Britain: a best-seller, it made its young author’s name.

Estranged though the former friends had become, Adam still craved Shiela’s approval for his political views. To Adam, always trusting in England’s underlying attachment to his beloved homeland, it seemed possible, even in the summer of 1939, that a deal might be done. The details of that plan belong to a later chapter (26); here, it is only necessary to point out that Adam, while visiting England, disclosed part of the strategy for avoiding war to Shiela Grant Duff and that she, under-informed and deeply alarmed, used her connections to help ensure that the proposals went no further.

On 25 August, one week before Germany’s invasion of Poland, Adam wrote to Shiela for one last and bitter time, to lay responsibility for the destruction of his mission for peace upon her own ‘complete incapacity to understand a naturalally’.10 With that, their correspondence ended. A collaborative friendship between a principled English woman and an idealistic German man – an alliance that once blossomed into something close to love – had reached a point beyond which there was nothing left to say.

Footnotes

* Ribbentrop’s Anglophile predecessor, Dr Leopold von Hoesch, had died in office, in sudden and faintly suspicious circumstances. His swastika-adorned coffin was paraded down the Mall and hailed from the Embassy’s garden terrace with a fusillade of rifle-straight outstretched arms. A modest memorial tablet to Hoesch’s dog (‘Giro: A faithful companion’) survives in a small fenced-off area beside the former Embassy.

* Jonathan Steinberg has kindly drawn my attention to the fact that Adam was also romantically involved at Oxford with Ingrid Warburg, of the great banking dynasty. (Ingrid Warburg-Spinelli, Erinnerungen: 1910–1989 (1990), pp. 109–123).

* Many German-speaking Saarlanders resented an enforced integration that cut them off from Alsace-Lorraine, their main source for supplies, and introduced a regime of terror. One old lady who poked light-hearted fun at the Nazis to the shopkeeper in her local grocery store reached home to find that the Blockleiter had already issued a warning to her husband. Their house was kept, thereafter, under close surveillance: correspondence was censored, card games were forbidden, visitors were monitored. (Interview with Mary Ann Dickinson about the experiences of her Saarlander grandmother, Anna Schneider, 5 September 2010.)