The Far North has two histories, a secret one in which—just like life— anything goes, and a conventional "on the record" version where propriety is prerequisite for starring roles. So credit for making the harsh frontier more livable and civilized is generally given only to a handful of "respectable" female pioneers. Emilie Tremblay proudly claimed the honor of being the first white woman to take the Native route over Chilkoot Pass to the great northern gold fields. A very respectable twenty-one-year-old French Canadian bride, in 1894 she had followed her husband, Pierre-Nolasque, to Miller Creek in Alaska, about 200 miles north of Fortymile.1 Church historians gave Mrs. T. H. Canham credit for being the first white woman into Yukon Territory, which she and her husband, an Anglican missionary, crossed during their five-month journey to Tanana Station to establish a mission in the summer of 1888.2 Charlotte Bompas, wife of the Anglican bishop at Buxton Mission, was presented the gift of a splendid gold nugget by Fortymile miners in 1894 for being the "first white lady who has wintered among us."3

All these "firsts," however, actually belonged to a well-known prostitute, "Dutch Kate" Wilson, who beat Mrs. Canham by one full year and Bompas and Tremblay by six. Traveling on her own initiative in 1887, she exhibited both fortitude and feminine whimsy.

Kate Wilson's trip over Chilkoot Pass was recorded by William McFee, who the following year would become the first man to bring in horses via that route.4 Her personal and financial arrangements with the small party of prospectors who accompanied her are not known, but John Rogers, a Yukon miner who fell in with them on the lower Yukon, clearly identifies her as "one of those poor, fallen women who are often found casting their lot with the mining class," adding with disapproval that "the poor creature, in order to better enable her to undergo the hardships of the trip, had donned male attire."

Yet, to Rogers's bemusement, just before reaching a large, isolated Native village, Kate "arrayed herself in her finest apparel, powdered her face, and arranged her bangs in her most bewitching style."5

The Indians had never before gazed upon a pale-faced woman, "and this apparition of loveliness had an astonishing effect upon the gentle creatures," Rogers conceded. "They greeted her with exclamations of delight and the Chief detained her at the boat until the women and children could run to the lodges with armloads of their wild goat wool blankets which they spread for Kate to walk upon the whole distance to the village."

Kate had difficulty evading the persistent demands of the old chief, who "pressed her to share his lodge and the exalted position as chieftain of a great tribe. This unfortunate woman had a series of adventures during the summer that would read like a romance," Rogers reported, leaving the reader hanging for details.

Prostitutes were usually the first women to reach early gold rush sites, but the Far North had been slow to attract them. Although Alaska was always wonderfully rich in natural resources, in the century that followed the Russian discovery of 1741 it offered little market for the sale of virtue. Early wealth in the form of sea otter and fur seal skins went to Russian freebooters, who initially took Native women by force. The majority of the invaders were Siberian outcasts with no motivation to return to their mother country, and most settled in the areas where they hunted with Native crews, ultimately becoming accepted by the locals and marrying in.

Whaling and sealing crews from many other nations followed, but few spent much time ashore in any one location. Nor was there a major center for the fur traders who spread throughout the country. And while some outsiders made romantic alliances, they tended to favor legal or quasi-legal marriages with Natives as had the Russians, because in addition to their charms, Indian and Eskimo women were adept at living off the rugged land and could help them survive.

Native women, whose societies openly accepted human sexuality, occasionally "traded" their favors, but there was no shortage of wives, no stigma in divorce, and little ready cash. Thus prostitution as we know it did not exist in the Far North until Alaska was purchased by the United States. Even then it was slim pickings for professionals because of low population density and a decline in the lucrative sea mammal fur business. About the only ready cash came from the American military, a minor presence on a tight budget.

"In spite of the total absence of any kind of serious work, and consequently earnings, almost all of Sitka [the capital] gets drunk daily, is unruly, fights, and so on. Another contamination is raging here, not any less than inebriation—that is chasing the women," lamented Stephan Mikhailovich Ushin, a Russian clerk who stayed in the largest city in the Far North—population about 500 with 250 soldiers—after the Alaska purchase in 1867. "Prostitution is spreading here very rapidly and thanks to this development the social life does not have a family order. Until the arrival of the Americans, and especially of their soldiers, there was here some kind of balance in this respect, but with the raising of the American flag, the entire life of Sitka has been refashioned to the detriment of the whole population."6

Most of the American women in the area were married, for there was little to lure single women several thousand miles from civilization into country where the only real economy was minimum wages paid to a small detachment of soldiers, soon to be withdrawn. The troops moved south in 1871, and gold would not be discovered in paying quantities for nearly another decade.

The first prospectors in the Far North were described as a breed of lonely, restless men. "The vanguard of them came in time through Sitka and Wrangell to the Stikine, and followed that river inland into Robert Campbell's unhappy, hungry country [northwestern Canada]," Allen Wright wrote in Prelude to Bonanza. Since the California rush of 1849, these men had drifted north through the mining camps of Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and Idaho.7

Footloose, driven by "gold fever," few were the marrying kind. Most were reconciled to living without women, since success eluded them and prospects took them not only far from "civilization" but beyond Native population centers as well. Those inclined to matrimony generally took Native wives, who were used to a migratory lifestyle and knew how to live off the harsh land.

An unfortunate exception was James M. Bean, who brought his wife to help set up a trading post at Harper's Bend on the Tanana River in 1878. Local Athabascans, unhappy with the Beans' prices, lay in wait for the couple, ambushing them at their campfire one night. James Bean managed to escape, but Mrs. Bean was murdered, and apparently neither the government nor Mr. Bean himself made any attempt at reprisal.8

While few females cared to follow in Mrs. Bean's bloody footsteps into the Interior, several minor rushes occurred in British Columbia, reached via the former army post of Wrangell on Alaska's southeastern coast. This community spasmodically supported a few professional prostitutes, but most of the females there were Indian women, who were often brutally assaulted by the men.

"In 1877 and 1878 several hundred miners from the British mines in the Cassiar district came down to Fort Wrangell to spend the winter, and spend their earnings of the summer in intemperance, gambling, and licentiousness," stated a congressional report.9 "They turned the place into a perfect pandemonium, debauching the Native women. They went into one Native house, made the Indian woman drunk, and then set fire to the house without any effort to rescue her from the flames, so that she was burned to death."

Wrangell was quickly upstaged by a major gold discovery on Gold Creek in the Silverbow Basin (about 150 miles north on the same coast), which led to the founding of Juneau in 1880. Diggings near this Alaska port at the headwaters of Gastineau and Lynn Canals were so productive that a "beer tent" immediately went in business in nearby Miner's Cove, followed by establishment of the Missouri (later named "The Louvre"), which was Alaska's "first and finest saloon." James Carroll, Alaska's first mailboat captain and later a delegate to Congress, bought the Occidental Saloon (established there in 1881), decorated it with mirrors, and turned it into the Crystal Palace and Ballroom, which became the centerpiece for Alaska's first major red light and bootlegging district. According to early accounts, liquor was brought into the Palace (which was built on pilings) through a trapdoor in the floor at high tide, while upstairs ladies of the evening entertained in "Kinsington Rooms," which actually remained in operation until 1954.10

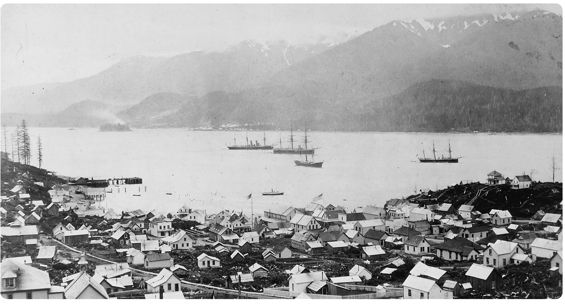

JUNEAU

The scene of one of Alaska’s earliest gold rushes, Juneau was a well-developed town by the time of the Klondike strike. Its sheltered anchorage made it a gateway city to the interior of Alaska and Canada.

UW #18027.

An 1887 newspaper account listed the assets of the town as "forty white ladies and 1,000 dogs,"11 and occasional discreet referrals were made to "ladies" from visiting variety shows and dance halls.

Miners kept early gold strikes relatively quiet, not wanting competition, but rumors of extraordinary prospects in the Interior began to circulate. Chilkoot Pass, the Indian route into this country, had been blocked by hostile Tlingits until 1880, when the U.S. Navy helped negotiate safe access for miners.12 Several prospectors who also traded furs—Edmund Bean, Arthur Harper, Napoleon "Jack" McQuesten, William Moore, and Joseph Ladue—scouted the country via both the pass and river routes, and also financed others to prospect the vast, unexplored region. Yet although Jack McQuesten was headquartered for years at Fort Reliance, only six miles from the later site of gold-rich Dawson,13 no major strike would be made there for another decade. Frustrated, McQuesten abandoned that area in 1887 and moved about seventy miles west to Fortymile, where two brothers named Day began panning out about $200 a week.14

The Fortymile River proved treacherous, taking at least seven lives during the initial stampede.15 Food was so scarce that some worried about starvation. Unlike Southeast Alaska with its relatively mild climate, in Fortymile country winter claimed eight months of the year, with heavy snows and temperatures that dropped as low as 70 degrees below zero and routinely hung in at -50 Fahrenheit.

Yet, at last, there was incentive for white women—both those who were respectable and those who were not—to move north. Gordon Bettles, traveling with George "Tuck" Lambert, one of the Fortymile discoverers, found "Dutch Kate" Wilson ensconced there in the spring of 1888, and noted that she was the first white woman to reach the newly built Canadian boomtown.

"She had come in the summer of 1887 via the summit and had landed one ton of provisions, expecting to remain for some time," he wrote. "After her experience in the winter of '87-'88, she decided to dispose of what remained of the ton of provisions she had landed with and return to Dyea."16

Bettles reported that men in the area were panning from twenty to one hundred dollars per day, and he gave no inkling of what had discouraged the seemingly unflappable Kate Wilson. About 250 men had been in the makeshift camp of log hovels the summer she arrived. Fifty wintered over, and any man who did not have gold to purchase a winter's supply of food by August 1 had been allowed to set up his rocker on paying claims.17 Obviously this economy could have supported at least one prostitute, but then it was a rough camp, answering only to miners' law.

Whatever Kate's reason for wanting out—the tough crowd, personal reasons, or perhaps just the rotten living conditions and fearsome climate—she had sold all but ten pounds of beans by the time Bettles returned to Fortymile after losing his own outfit. "We bought the beans and sometime later she left for outside," he noted.18

When Kate's mining companions descended the Yukon that fall, they had difficulty obtaining passage on the revenue cutter that visited St. Michael. According to one Oregon newspaper account, the captain of that U.S. government ship "absolutely refused the girl passage and she was left on the bleak Arctic shore at the mercy of the Indians and the missionaries. The following spring a sealing vessel which sprang a leak off the mouth of the Yukon and put into harbor for repairs, picked her up, and she returned to Southeastern."19

That Kate Wilson survived to pursue other ventures is borne out by a later newspaper account about the town of Douglas (near Juneau), recalling when "Dutch Kate's dance hall and the little Friend's Mission on the hill contended with grim aloofness for the grip on the souls of men."20 And Kate may well have gone north again, for in the Wickersham Collection there is a photograph of a beautiful Dawson prostitute known only as the "Dutch Kid." The usually thorough Judge James Wickersham, perhaps purposely, included no last name in his caption, but noted with satisfaction that the woman had done well enough in her trade to go back to school and become a nurse.21

The tempo of the gold rush picked up in the Interior when Fortymile miners began moving to Circle, an American boomtown with better prospects, some 200 miles northwest. Established in 1892 following gold discovery by two Creole Natives that produced $400,000 during its first season, Circle City soon became the largest log cabin town in the world.22

Its success spawned the Far North's first bona fide demimonde, that strange "half world" of dance hall girls, legitimate actresses, and prostitutes, women who elsewhere would have been relegated to the outskirts of society but in that nearly wifeless community became the center of the social whirl. Theatrical promoter George T. Snow, a dedicated family man, may have inadvertently introduced its first contingent when he imported a troupe of "dance hall girls" to Circle from San Francisco.23 Others began to trickle in from Juneau to work both Circle and Fortymile.

"These women had a hard time in the wilds of the subarctic forest, but they were also amply rewarded by the miners for the 'display of their talents,'" noted historian Michael Gates. "They were certainly a change from the Native women, to whom most of the miners were accustomed. One of these women boasted of receiving a gold nugget from a miner for agreeing to have a date with him. To her embarrassment, the nugget weighed out at a value of eighty-five cents, and she was forever after known as 'Six Bits.' Another, the youngest of the troupe, was lovingly known as 'The Virgin' because, the miners thought, she had actually seen one."24

Anna DeGraf, whose arrival in 1895, just before the dance hall girls, swelled the number of respectable women in Circle to eight, noted that white men sometimes "purchased wives from the chief of the [neighboring] tribe, giving provisions and blankets in exchange. Some of the young girls were sold when they were twelve years old, and many of them had sweet faces."25

Anna DeGraf voiced concern that, by attracting the attention of local men, the showgirls caused otherwise faithful husbands to neglect their Native wives. However, the outsiders also became the focus of violence and exploitation that previously had been committed mainly against Native women.

Anna once protected a dance hall girl from a gang of six miners, wielding a gun to stand them off. The girl had angered the men by objecting when they began to "roughhouse" in her cabin. "Because she protested, they had set her on her cook stove, which was red hot," Anna recounted, "... as a result she was painfully burned and was groaning and suffering terribly." And, although Anna was fifty-six at the time, the attractive seamstress barely escaped molestation herself.26

Early accounts show that Circle "miners' courts" sometimes dealt unfairly with women of the night, and the American government provided no protection for them. However, one reason the whores had been attracted to the camp in the first place was because of its lawlessness. Their pimps, the bar owners, gamblers, and confidence men—even the miners themselves—preferred Circle because, unlike Fortymile, it wasn't under the jurisdiction of Canada's watchful Northwest Mounted Police. With the enthusiastic patronage of this pioneer underworld, the American camp grew sophisticated enough to be called "the Paris of the North."27

"Of course, few miners on the Yukon River in the mid-1890s had seen Paris recently," history professor Terrence Cole observed dryly. "After one winter in the arctic bush, however, when a prospector discovered a town with about 1,000 residents, 300 sod-roofed log cabins, several two-story buildings, twenty-eight saloons (including one with a pool table and a billiard table), eight dance halls, a free circulating library of 1,000 volumes (including a complete set of the Encyclopedia Britannica), a brewery, a log schoolhouse with a female schoolteacher, a barber shop, a local debating society, an opera house, and most of the twenty white women who lived in the entire Yukon Valley, he might well cherish the memory of the first time he saw Circle City on a spree."28

Circle was, in reality, a rather dismal, primitive place with outrageously high prices, inadequate supplies, no running water, electricity, or sanitary facilities, and no easy way out eight months of the year. Yet there was good money to be made—far more than in the depression-ridden world outside—and things could only get better. A bigger gold strike was coming. The old-timers who had seen prospects improve steadily for a quarter of a decade were even more certain of it than the wildly optimistic newcomers.

CIRCLE CITY

Called the “Paris of the North.” this Alaska outpost was rough-hewn with very few amenities in its early years. The population, gathered for this photo at Jack McQuesten’s trading post, was mostly male.

UW #899.

"No, Henry, you stay here, somebody is going to make a big strike here soon for sure," aging trader Jack McQuesten assured a friend.29 Excitement bordering on hysteria was in the frozen air. Many had mortgaged their futures and risked everything, including their lives, to wager that the big one was coming. And—gamblers all—they were right!

It seems fitting that many of those who had endured hardship and deprivation to survive in the Far North would be there in the summer of 1896, ready to take advantage of the strike of the century in Dawson. Jack McQuesten quickly set up shop in the budding boomtown, within walking distance of where he had unsuccessfully established Fort Reliance in August of 1873, and shortly thereafter retired to California with his Athabascan wife and daughters, a wealthy man.30

"Swiftwater" Bill Gates, so unsuccessful at prospecting that he had no money for a grubstake, was slinging hash in a Circle restaurant when he overheard two customers talking about the Dawson strike. Leaving their dirty dishes in the sink, he headed upriver, where he secured rights to a claim worth more than a million.31

Former fruit farmer Clarence Berry, who'd prospected for years with little success, happened to be on duty as a bartender at Bill McPhee's Saloon when Antone Stander, an Austrian who had just staked on Eldorado, was refused credit at the Alaska Commercial store. By providing the needed groceries, Berry became Stander's partner and was on his way to becoming one of the most successful Klondike Kings—and one of very few who would parlay their earnings into an enduring fortune.32

Harry Ash, a Circle dance hall operator, hauled his piano (on which most of his girls had scratched their names with hat pins) to Dawson and averaged $3,000 per day in the profitable new location.33 George Snow's Dramatic Company with "The Virgin," "Six Bits," and the lovely Gussie Lamore immediately headed for the new boomtown, where the talented actor/producer would make more money in gold than he did in theater.34

Credit for being the first white woman on the scene was claimed by Lotta (a.k.a. Lottie) Burns, a pioneering prostitute who had come to Circle from Fortymile in the first wave. Few who knew her begrudged her the honor, but most were bemused at her self-styled title, "Mother of the Klondike," for she was not exactly the motherly type.

Belying the stereotype of the hooker with a heart of gold, Lottie Burns was, by all accounts, an unabashed opportunist. She had good looks and charm enough to beguile an enamored steamboat captain out of $500 for her initial "grubstake," and was said to have delighted in ruining men.35 In 1896, one year after her arrival in Circle, Lottie was found guilty of defrauding another prostitute, but managed to get off with a suspended sentence. Later she made big bucks purchasing mining claims at bedrock-bottom prices from men with heavy gambling debts and other hard luck sagas, which did not endear her to the Klondike's tight little fraternity of prospectors.36 A mining camp jingle, probably composed in her honor, reflects local ambivalence:

Lottie went to the diggings!

With Lottie we must be just

If she didn't shovel tailings—

Where did Lottie get her dust?37

Despite her unsavory reputation—or perhaps in an attempt to repair it—Lottie gave an extraordinary interview to the Seattle Post Intelligencer in the fall of 1898, telling a sympathetic rags-to-riches story, a bit skewed by her omission of a few pertinent facts (like her profession) but undoubtedly laced with truth.38

According to this account, Lottie had a mother to support in Montreal. Tiring of the hard work she was compelled to do six days a week in a dingy factory, Lottie boldly struck out for Alaska to seek a fortune, "unmarried and alone." Without giving the trusting P.I. journalist any hint of how she acquired her capital, she explained that she went to Circle City to invest in town lots. "She was a shrewd woman, and by careful manipulation succeeded in getting a few thousand dollars," he reported breathlessly. "This she invested in mining property, buying mostly from owners who had gambled away their earnings and were willing to sell interests to their claims at small prices."

When the strike at Dawson was announced, Lottie immediately "bought some town lots and put money into other ventures until she had raised considerable capital," according to the article. Then she visited Montreal, where "she placed her mother in comfortable circumstances for the rest of her life."

Lottie returned to Dawson in August of 1897 with a bicycle—"the first ever in the Klondike"—which she apparently intended for her own amusement, but when miners' bids for it reached $700, she sold like the hard-headed businesswoman she had become.

During her interview, Lottie spoke with concern about the plight of the Indians "who were dying by the score on the lower Yukon" from diseases brought by the white man, particularly consumption. Then, taking full advantage of her public podium, she angrily denounced the lawlessness and confusion of mining regulations on the U.S. side of the border— perhaps remembering privately her own unhappy experiences in American miners' court.

Yet the "young mining woman," as she preferred to be called, was optimistic about the future of the Far North and savvy enough to know that the great stampede had only begun. At the time of the interview Lottie Burns was once again headed north, hell-bent on making another fortune.