Luther Hess had come home to Milton, Illinois, for a visit. Georgia Anna spotted him on the stern-wheeler up from St. Louis, dressed like a prince, sporting a watch fob with gold nuggets as big as robins' eggs. He noticed her, too—who wouldn't! At age twenty-six she was lovely: five-feet-two and with huge gray eyes, thick, straight dark hair, and a perfectly proportioned figure. She hoped he would introduce himself, but she was in the company of one of her traveling salesmen and Luther kept his distance.

Later, her patron—a wealthy businessman with important political connections from Detroit, Illinois,1 so prominent that Georgia was forbidden to tell anyone (especially his wife) that she knew him—decided to show her off to Luther Hess. That was his mistake.

The Hess family was about the richest for miles around. Now Luther was making money of his own at some new Alaska gold camp called Fairbanks, the Detroit businessman told Georgia. Actually, Luther was a lawyer and a competent one, but he'd done even better in mining. Georgia Anna's patron said Luther Hess had a good eye for investments, and he was right. What he didn't know was that Luther soon would decide to invest in Georgia Anna.

Georgia didn't need to be told that the Hess family was wealthy. Since her childhood she'd gazed with envy at their seventeen-room white house, crowned by its stately cupola. It was still a farm, but nothing like the miserable, patch-together farms where she'd grown up.

Georgia's mother, Sarah Callender, was from a family almost as well-heeled as Luther Hess's, but they gave her no help in 1865 when at age seventeen she bore William Eldredge a daughter, Nancy.2 Eighteen months later, William ran off to marry Harriet Daniels, and when Sarah saw the match would stick, she wed Aaron Harrison because it was tough supporting a baby on her own.3 Harriet died in 1874, leaving William Eldredge with two young children, Margaret, age eight, and John, age two. William knew that Sarah still had a weakness for him and talked her into marrying him that same year.4

Their second child, Georgia Anna, was born in 1877. She was unusually beautiful and the Eldredges would have been pleased except that William was not strong and was having trouble holding a job. The family drifted between the small farming communities of Milton, Detroit, Pearl Station, Florence, and the county seat of Pittsfield, trying to make a living.5

When Nancy was fourteen and Georgia Anna only three, their father died of pneumonia,6 leaving Sarah alone to provide for them and their step-siblings, John, seven, and Margaret, thirteen. One year later Sarah wed Thomas Crossman in what might have been a match of desperation,7 for she could not support four children working as a cleaning woman or a cook, the only positions open to her. Nor did Thomas have many resources, so even after she married him Sarah hired out to the Daniels family, often bringing her children to help.

At age seventeen Nancy escaped her family's bitter poverty by marrying Wilbur Daniels, a son of the farm owners, and moving to Florence. Margaret married John Couch from neighboring Nebo.8 The obvious replacement for her older sisters, Georgia Anna was taken out of school, where she had been doing well, to supplement the family income by serving as a household drudge.

She hated it! Life as a "hired girl" in that farm community meant working ceaseless twelve-hour days, cleaning, ironing, toiling over hot stoves in the devastating heat of summer, and mopping floors and doing laundry in winter when it was so cold the wash water froze.

Georgia Anna had watched her mother, locked in a loveless marriage, grow prematurely old in her grueling struggle to raise her children. Marriage hadn't gotten her sister Nancy much either, except two howling babies to look after, with another on the way. But Georgia Anna had a way out. Men, she quickly discovered, would give her almost anything she wanted. Her beauty, her astonishingly deep, husky voice, and her penchant for having fun made her a standout in their community of plain, overworked farm women. Men really liked her, and she really liked men.

She recruited the help of James "Ben" Daniels, her sister Nancy's brother-in-law, who worked as a bartender on the Eagle Packet Line. He was five years younger than Georgia Anna, but he was sweet on her and would do whatever she told him. With his help, she began to slip away from the farm to visit Nancy in the nearby port town of Florence. It gave her a chance to check out the Yellow Dog Saloon across the river, where the prostitutes worked, and to ride the packet boats to St. Louis.

Horrified, her mother turned to the church, insisting Georgia Anna be baptized with her brother, John Owen, in 1892. But Georgia Anna saw no future in religion and soon made her base of operations with Nancy and Wilbur Daniels in Florence.9

Word got around. "It was common and general knowledge in the vicinity of Milton, Detroit, and Florence, Pike County, Illinois, that Georgia Anna Eldredge was a 'wild woman.' She was always with a man and was used for immoral purposes frequently, both on the boats and during her stay in St. Louis," Captain Harry Lyle of the Eagle Packet Line reported. "Boatmen would tell you that she would get a man when the boat docked in St. Louis."10

Ben Daniels continued to be useful to Georgia Anna. He wasn't her pimp, exactly, but did help her get transportation on the river. He also kept an eye on her dealings with the riverboat men and drummers who stopped at the Finny Hotel, in case she got into trouble.

It was during one of Georgia Anna's stern-wheeler rides that she was noticed by Luther Hess, and he later told her about the high demand for love in the Far North. A clever girl could easily make $100 a night, he said, and he was certain she'd do well. However, Luther insisted that she learn the trade before she came north. He knew someone in St. Louis's red light district who would show her all the tricks. Of course, she would earn while she learned.

Excited, Georgia told the news to Ben Daniels. He was skeptical.

"Shoot," he said, "Ol' Lu's been telling anyone who will listen they can make a fortune in Alaska. But why would you go? You're making a fortune right here."11

Granted, she was doing better than Ben, but the townsfolk held a low opinion of her and so did most of her kin.12 She didn't want to spend the rest of her life working backwater farmers and packet boat men because they never had much cash. She could probably sweet-talk her prominent patron into setting her up. But Georgia Anna suspected she could do better, especially if Luther Hess thought so.

Georgia Anna's last confrontation with her mother—probably about 1903—could not have been pleasant. Sarah was humiliated by the gossip and unimpressed with her daughter's newfound earning power. Georgia Anna left without mentioning her plans, and Ben Daniels, faithful and discreet as usual, drove her to Florence to catch the boat for St. Louis. To his astonishment, Luther Hess was waiting for her.

"Well, I'll see you someday, Ben," Luther said awkwardly as Ben saw the couple off. Georgia Anna kept her peace. She knew she would never see Ben or any of her family again. She also knew they'd feel more relief than pain when they discovered she had run away. Most of them hated what she had become.

Ben decided to tell no one that Georgia Anna had gone off with Luther. He kept the secret, but word spread quickly that she had become an inmate in a "red light house." Her Detroit patron began finding excuses to visit St. Louis, and he wasn't the only Pike County resident following her career. Ben's fellow crew members boasted of seeing her in the "house" on various occasions, and so did local farmhands.

"All the boys used to wait eagerly to fatten a hog enough to take it to market in St. Louis so they could see Georgia," Ben Daniels later recalled with a wistful smile. "Luther Hess came back to visit Milton many times but he never mentioned Georgia Anna Eldredge and I never asked. I figured it was none of my business."13

By 1906 Georgia Anna was established in a fine brick duplex at 4753 Michigan Avenue, a quiet, brick-paved street near Carondelet Park. Her residence was west of the red light district, yet conveniently near the docks. Listed in the city directory under the name Georgia Lee, she could afford a telephone14 and succeeded at her calling without once getting arrested. She had developed a taste for fine furniture, high fashion, and good whisky. She could curse like a stevedore, but could also pass for a lady when she cared to. The rough edges of her rural upbringing were gone.

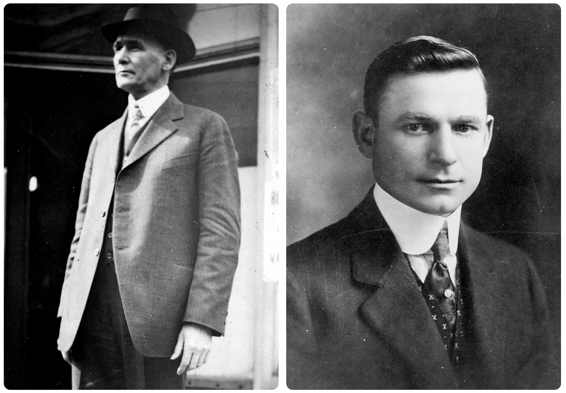

LUTHER HESS (left)

A well educated lawyer from a wealthy family in Illonois, Luther was among Fairbanks’s first settlers and soon became city attorney. Later he became the wealthiest man in town, investing in banking, gold-mining, and Georgie Lee, who came from his hometown.

UAF, V.F. Addendum Historical Photograph #82-02-56N.

CHARLES THOMPSON (right)

Also pioneering Fairbanks was bar owner Charles L. Thompson, who made a fortune, partly due to his underworld connections. An avid sportsman and gold camp booster, Charles was highly popular with both Fairbanks citizens and numerous ladies of the red light district. Georgia Lee was the first to capture his heart, but lost him to a French protitute called “Mignon” Miller.

From Alaska Probate Records, Juneau.

Luther Hess had reason to be proud of his prodigy, and that summer she moved to Fairbanks where he quietly backed her business. Luther had just resigned his position as assistant district attorney to help organize the First National Bank of Fairbanks. The venture was successful. He became the bank's director and began pumping his personal earnings into mining property. And Georgia Lee proved one of his most useful early assets.15

The raw boomtown of Fairbanks must have been a comedown for Georgia Lee after the elegance of St. Louis, but Luther Hess had predicted correctly that the Fairbanks stampede would be worth getting in on. Over 8,000 stampeders were in town. Gold production had topped $9 million, and Georgia Lee discovered the money was even better than Luther had promised. She worked out of a tiny cabin in the new restricted district, where bartenders at the Floradora Dance Hall, the Fast Track, and the Seattle Saloon would send her customers on commission. A nearby downtown area called the Great White Way had several blocks of bars and gambling dens that never closed.16 Most of her clientele were mining men, tough but clean-cut, fun to be with, and free spenders.

Georgia quickly repaid her debt to Luther, but continued to help when he had cash flow problems. In return he advised her on investments, but otherwise she saw little of him. As the former assistant district attorney and now a respectable banker, Luther had a reputation to maintain, and Georgia's attention was elsewhere. 17

She'd fallen in love for the first time in her life. Her man was bar owner Charles Thompson, not quite thirty, not quite six feet tall, but extremely handsome with blue eyes and wavy brown hair. He was a flashy but careful dresser with a ready wad of big bills always in his pocket, and his hands flashed with real diamond rings. He loved sports, especially baseball, and had an affable charm that endeared him to the general citizenry, even though most suspected that he had ties to the underworld.

Charles Thompson also had more sex appeal than Georgia had ever encountered. The attraction was instant and mutual. Charles had played the field for years, but he fell hard for elegant little Georgia Lee. For the first time in Fairbanks he asked a woman to live with him, and Georgia agreed—although she continued to ply her trade.18

There were repercussions. No sooner had Georgia hung her silk negligee in Charles's closet than the marshal busted in to charge them with adultery. At first they thought it was a joke, but it turned out the hotshot new federal district attorney, James Crossley, was trying to make a name for himself by staging raids all over town. Charles's attorney, Leroy Tozier, said the list read like a who's who of Fairbanks, and it would have been embarrassing if Charles hadn’t been on it. Everybody knew the charges were ridiculous, because neither Charlie nor Georgia was married. However, they could have been convicted of "cohabiting in a state of fornication," so at Tozier's suggestion Charles paid the adultery fine of only fifty dollars.19

Otherwise, life was good. Charles gave Georgia diamonds and pretty clothes, and they moved into a fine apartment he built over the Tanana Club, his elegant new bar. His goal was to become rich, and watching him parlay his small holdings into the finest drinking establishment in town was not only exciting but an education for Georgia. Charles also began accumulating property on the Line, and moved toward gaining control of the town's gambling and bootlegging operations.

Charlie said little about his past, although he did share his dream of returning to Bay City, Michigan, to dazzle his parents and three sisters with his affluence—once he acquired some. He had not been in touch with them since he left home at age seventeen in 1895. He had connections with major underworld figures in the "Syndicate," who apparently backed some of his Fairbanks investments. But Charles was respected locally, and Georgia Lee found him a square shooter. His real name, she discovered, was Leo Kaiser, but that didn't seem strange because she'd also changed her name. His world became hers, and she could not imagine life without him.20

However, Georgia had always been independent, and she took Charlie for granted, which was a mistake. She failed to notice when he started spending time with a leggy French prostitute who had an evil temper and an impressive police record. Her real name was Josephine "Louise" Therese Vassiaux, but she'd made a reputation for herself as "Mignon" Miller, Gabrielle Mitchelle, and a few other aliases.21

Arriving in Fairbanks from Dawson about 1905, Mignon had attracted attention when a dog from Deputy Marshal A. H. Hansen's team, detour-ing through the red light district, snapped up her small poodle from the sidewalk and tossed it over its head at Hansen, where it dropped dead at his feet. Mignon, garbed in a kimono and red satin slippers, cursed the driver in heavily accented English for more than ten minutes, never using the same vile name twice. When a crowd gathered, she threatened to kill the offending animal, the team, and Hansen himself.

Later, Hansen gave Mignon's business manager the money to buy her another dog, but no one doubted that Hansen was a marked man. "She'll kill you sure as hell," the manager warned him.22

Georgia had never considered the French whore a rival because she was not beautiful and may have been older than Charles. Yet in the spring of 1910, Charlie moved Georgia out and Mignon in.

Devastated, Georgia downed a handful of antiseptic tablets, but friends countered with prompt applications of olive oil and a stomach pump. Two weeks later, recovered physically but not mentally, Georgia invaded Charles's Tanana Club early one morning armed with a Colt automatic, looking for Mignon. Thwarted, she began smashing Charlie's fine furniture. It took the marshal and four deputies to carry her, spread-eagle, off to jail, where she was charged with disorderly conduct. On her release Georgia swore out a warrant against Charlie for abuse, but she soon dropped charges and made peace, both with her former lover and with Mignon.23

Then Georgia Lee began to focus on getting rich. Mignon had been arrested that fall for selling liquor without a license and escaped prison only because the federal witness against her had vanished before the trial.24 No doubt Charlie Thompson's underworld connections had helped on that one, but Georgia wanted to make good on her own.

Easy pickings in Fairbanks were a thing of the past. Gold production had slumped but a new discovery had been made in Livengood, a rough camp one day's journey north. Few Fairbanks girls cared to give up their comforts for it, but several hundred prospectors were in residence and Georgia Lee decided to pioneer the area.

Since the camp had few women and no restricted district, Georgia set up shop next door to her friend Blanche Cascaden, the rough-and-tumble owner of a fair-sized mining operation. After a couple of failed marriages, Blanche had come to Alaska from Dawson with two young children to support, and made a happy match with John Cascaden, who subsequently staked profitable mining ground in Livengood. When he died unexpectedly, claim-jumpers tried to take the property, but Blanche had fought them off with her shotgun from a hill of pay dirt. She became known as one widow it did not pay to mess with.25

Another neighbor was a blond, blue-eyed French "housewife" known as Mrs. Belle, who had been imported from San Francisco's red light district by "Two Step" Louis Schmidt, a veteran prospector. "Two Step," who got his nickname because of his limited dancing repertoire, had made and lost several fortunes. He was considerably older than Mrs. Belle and when he got up in years, he suggested she divorce him and find someone younger. She complied, marrying a well-paid timekeeper for the Fairbanks Exploration Company, and keeping a boyfriend on the side. Like Blanche Cascaden, Mrs. Belle had a keen mind for finances in an era when the "weaker sex" seldom considered business ventures of their own. Both Blanche and Mrs. Belle had taken firm control of their resources, and Georgia Lee quickly followed their example.26

After making good money in Livengood, Georgia moved on to Nenana, where she invested with foresight. The federal government was building a railroad from the coast to Fairbanks, hoping to bring down the cost of living and save the town. The railroad line's completion was a few years off, but Nenana, sixty miles south of Fairbanks, would be a major construction site from which hundreds of men would be deployed. Georgia got in on the ground floor, not only as a prostitute but as the owner of a fine home, a dress shop, and a legitimate hotel called the Flower.27

In 1923 the Fairbanks Exploration Co., attracted by the new railroad link to the coast, established a big mining operation in Fairbanks, hiring a thousand or more men to run its great dredges. Fairbanks thrived again and Georgia, who had sold out near the peak of the Nenana boom, had money to invest. What she didn't have was a business education, but her all-too-brief experience in the one-room schools of Pike's County had gone well enough that she thought she'd profit from college instruction.

Georgia turned to the new Agricultural College and School of Mines, which had just hired a bright young woman to teach business courses.28 College President Charles E. Bunnell, a straight arrow with little sense of humor, had served six years as Fairbanks's federal judge. Rumor had it he was so desperate to attract students to the fledgling university that he'd stooped to recruiting them from jail.

Still, he was thunderstruck when Georgia Lee arrived in his office, tuition in hand. She had dressed with restraint for the interview. Her police record was minor. But Georgia Lee was one of the best-known whores in the Far North, and President Bunnell refused to allow her to enter his college.29

Resigned, Georgia Lee returned to the source of her early training, Charles Thompson. By 1917, the height of Fairbanks's depression, he had accumulated enough wealth to seek out his mother in Bay City, Michigan, for his long-fantasized reunion, bragging to her that he owned the Tanana Club, a Fairbanks showcase. A year later fire destroyed the building, but Charles never looked back.

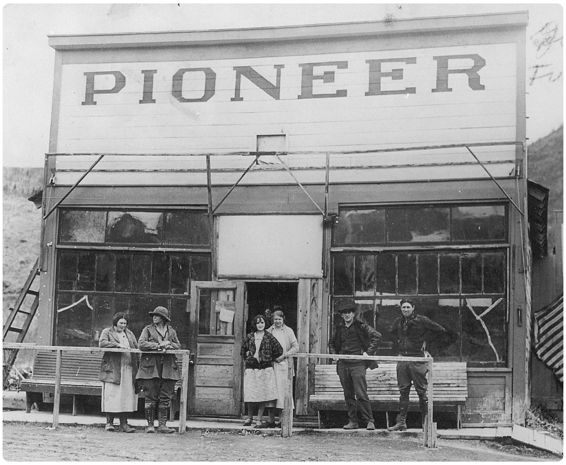

LIVING IT UP IN LIVENGOOD

Georgia Lee made good money selling love in Livengood, a gold camp that boomed as Fairbanks failed. Here she is pictured, center, with her friend, mine owner Blanche Cascaden (in the hat) and bush pilot Joe Crossen, far right.

Blanche Cascaden photograph, courtesy of Orea and Cliff Hayden.

In Fairbanks's early years, Charles had befriended a bartender named George Akimoto who, as the front for a Japanese syndicate, had purchased considerable property on the Line. When Akimoto left town around 1913, Charlie moved to buy him out, investing with Georgia Lee to broaden his control, knowing she remained loyal to him.

In 1922, federal authorities attempted to eliminate the Line, forcing the women out of houses they owned and confiscating their property. Georgia hired Tom Marquam, the best criminal lawyer in town, to defend her. Working with Charlie Thompson to organize her colleagues, Georgia and Tom mustered enough opposition to defeat the unconstitutional action.30

Charlie and Mignon were still an item, but that no longer bothered Georgia. The French woman proved well suited for the domineering Charles, and Georgia Lee finally had found a true love of her own.

Tom McKinnen was a well-respected, well-heeled mining man whom she had met in Livengood. He was married to a woman known in Fairbanks as "Ma" McKinnen, who had been wild in her youth but settled into respectability to raise her two sons by another husband. The boys were grown now and one of them, Tommy Carr, had married Kitty O'Brien, who had worked with Georgia on the Line before successfully investing in a taxi cab company. In a town as small as Fairbanks, Tom McKinnen's family must have known of his romance, but the lovers pursued their relationship with a discretion uncharacteristic for Georgia Lee. In later years she would call it the happiest event in her life.31

Tom McKinnen may have helped Georgia with her financial planning, for she branched out from the restricted district to buy in respectable areas, soon making a good living on rents alone. She also purchased a small house for herself on Sixth Avenue, furnishing it lavishly. There Georgia cultivated friendships with her neighbors: city councilman John Butrovich, his wife Grace, and Ruth McCoy, the self-reliant wife of an iron worker, who occasionally cleaned houses on the Line for pin money.

Tom asked Georgia Lee to quit selling herself, and she promised she would. But she loved a good party and lots of her old customers still depended on her, so she quietly pursued her trade when her lover was out of town. Tom always sent for taxi driver Jim McClung when he was coming in from the mine, and Georgia arranged for Jim to warn her so she could return home from the Line in time to present a picture of domestic tranquillity.32 Actually, she was edging into it, increasingly occupied with her lovely garden and doing charity work when she thought no one would notice. With Ruth McCoy she helped organize a Fairbanks branch of the Humane Society, and she also had a soft spot for her young renters.33

In contrast, Georgia's former lover, Charlie Thompson, was going the opposite direction. He had made part of his fortune bootlegging after Alaska passed a "Bone Dry" prohibition law in 1916, and when a nationwide ban on alcohol went into effect he moved to take advantage of it through his underworld connections outside the territory. Without liquidating any Fairbanks holdings, Charlie departed for the States in November of 1930 with Mignon Miller on his arm and $110,000 in cash on his person. The couple, presenting themselves as married, settled in Chule Vista, California, not far from Tijuana, Mexico, where Charles bought the Red Top Distillery. Their affluence in the face of a national depression readily bought them a place in San Diego society. Alaskans who occasionally read clippings from California society pages, sent north by friends, were bemused to see photos of "Mr. and Mrs. Thompson" dressed in their finery, usually with luxury cars in the background.34

But Charlie's business was risky. Sometime in 1930, Mignon confided to friends that a distillery employee told her he had been offered money to murder her and Charlie and dispose of their bodies. Although that man had refused, the couple did receive extortion notes threatening Charles's life and demanding $5,000. Later that year Charlie had a noisy confrontation with his distillery manager, Hugh McClemmy. On January 12, 1931, McClemmy pleaded not guilty to federal bootlegging charges and was released on $10,000 bond.35

Charlie Thompson and Mignon Miller were last seen on December 5, 1931. A few casual friends received Christmas cards from them postmarked Tijuana, but police investigating the disappearance said many close friends received no cards and the signatures on those sent appeared to be forgeries.

The disappearance made California headlines for several weeks and, although the Federal Bureau of Investigation was called in, no trace of the couple was ever found. Nor was there an explanation for the disappearance at the same time of J. L. Summers, an engineer at their distillery who had worked with Charlie in Fairbanks. George Smith, an early Fairbanks mayor and a friend of twenty-two years who was Charlie's neighbor in California, appeared to have no clues.36

The search was called off in February of 1933. One month later, Charles Thompson's mother, Margaret Kaiser, opened his safe deposit box in a border bank near San Diego to find only $1,100 and some insignificant jewelry.37 No other large amounts of cash or valuables turned up. Hugh McClemmy, Charlie's partner at the Red Cap Distillery, served three years at McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary on the bootlegging charge without throwing any light on the mystery.38

When Charles and Mignon were declared legally dead five years later, their combined estate was worth only $33,611, of which $18,500 was from Fairbanks real estate holdings.39

DISAPPEARED

Georgia Lee made good money selling love in Livengood, a gold camp that boomed as Fairbanks failed. Here she is pictured, center, with her friend, mine owner Blanche Cascaden (in the hat) and bush pilot Joe Crossen, far right.Charlie Thompson and Mignon Miller disappeared in 1931 while living in San Diego and “rum running” from a distillery he owned in Mexico. Rumor had it they were murdered, but friends suspected they might have used their considerable assets to start a new life elsewhere.

San Diego Union, February 3, 1933.

Rumor had it that they had been robbed and murdered, reduced to ashes in the furnace of their Mexican distillery. But friends wondered whether, under threat of federal investigation or mob reprisals or both, the couple might have fled with their bankroll to build another life.

Georgia Lee, meanwhile, had parlayed her earnings into assets valued at about $100,000. She narrowly escaped charges of federal tax evasion because an Internal Revenue Service agent tricked her into paying. Warned in advance that she would be hard to deal with, the tax collector saved her for last when he interviewed all the inmates of the Line about their earnings. As expected, Georgia insisted she had no income to declare,- operating costs for clothes, refreshments, etc., had eaten up her profits, she said.

"Gee, Panama Hattie has declared $10,000," the agent said, giving the still-handsome hooker an appraising look. "I would think you'd probably do at least as well."

"Why that old has-been!" Georgia exploded. "Put me down for twice that much."40

Georgia's world dimmed when Tom McKinnen died, but his portrait remained prominently displayed in her home and she often spoke of him as "her man." Now in her fifties, she was courted by a number of much younger men, one of whom begged her to marry him. When she refused, citing their age difference, he phoned her friend, Blanche Cascaden, asking her to intervene. Blanche, who knew Georgia would never consider marriage because of her childhood memories, tried to break it to him gently. Calmly the suitor stated that he could not live without Georgia Lee. He asked Blanche to tell Georgia that he loved her. He had a gun at his head, he said. Then he pulled the trigger, leaving Blanche with the sound of the explosion echoing in her ear and the sad task of informing Georgia Lee and the police.41

In 1947 Albert Zucchini, a young entrepreneur from St. Louis, rented a building from Georgia Lee for his business in surplus war material, which he called the Auction. Scarcely taller than herself, Albert was one of the few men Georgia could look right in the eye, and she liked him right away. She also liked his partner, a good-looking World War II veteran named Johnny Williams.42

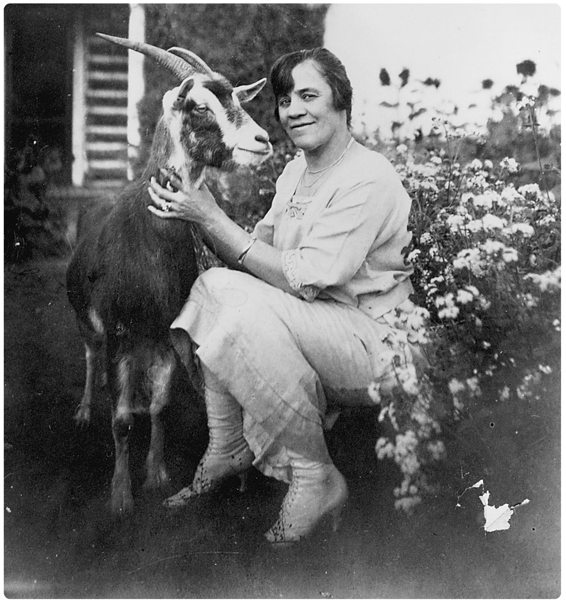

STILL WORKING

Georgia Lee promised her lover she would quit the Line, but quietly continued to work at her trade out of consideration for old and faithful customers. She also took interest in Fairbanks civic affairs and became co-founder of the Fairbanks branch of the Historical Society.

Courtesy of Rozena Stonefield.

Raised in upstate New York and an electrician by trade, Johnny had come to Fairbanks to operate a second-hand store after serving in the South Pacific. The venture was successful enough that he purchased a nice home. Only after it burned did he discover that he had no insurance coverage—his insurance payments had been pocketed by the disbarred lawyer who was his agent.43 Bereft of capital, he began working as a laborer and Georgia, who hired him as a handyman, found him handy indeed. He still owned a small house in North Pole, but quickly moved to a little cabin on Georgia's property. She became the focus of his life, having faith in his ability to recuperate from his losses when nobody else did, and loaning him $2,000 to make a new start.

In October of 1954, Georgia Lee embarked on a trip down the Alcan Highway to the States with her neighbors, Ruth and Louis McCoy. She had been suffering from chronic bronchitis and hoped to get sophisticated medical help in Seattle, but this was also a pleasure trip. Ruth McCoy had become one of Georgia's best friends. Like Georgia, Ruth had come up hard, helping raise six younger brothers and sisters after her father died. And, although Ruth wasn't in the trade herself, she did not look down on Georgia's profession. Ruth looked like a taller, younger version of Georgia Lee, and the two women had grown so close folks often mistook them for mother and daughter. The dusty auto trip was to be a real vacation for them. Instead, at Beaver Creek just over the border, Georgia Lee died quietly in her sleep from heart failure.44

Johnny Williams did not take the news well. He called several of their friends, including Blanche Cascaden, to break the news and inform them that he did not intend to go on without Georgia Lee. Few took him seriously, but within a few hours he shot his big black dog and then turned his .30-30 rifle on himself, dying instantly. He was fifty years old.45 Georgia Lee was seventy-seven.

Blanche Cascaden had wonderful fun with Georgia Lee's funeral notice, lopping five years off her birthdate and reporting that she had been employed as a cook in Fairbanks and Nenana after coming to Valdez. However, Blanche did give correct information about Georgia's hometown, which Ruth McCoy followed up on administering the estate. Apparently Georgia had told them she had no relatives, but they suspected differently.

Late in 1954, young Derald McGlauchen, a grandson of Georgia's sister Nancy, was loafing around the Milton, Illinois, filling station when the town mayor arrived with a letter, which he read aloud to everyone. It was from an attorney in Fairbanks, Alaska, seeking anyone related to Georgia Lee Eldredge.

NEIGHBORS

Ruth McCoy, one of Georgia Lee’s neighbors, was so close to her and so resembled her that many thought they were mother and daughter. Ruth had never worked on the Line but was tolerant of those who had.

Courtesy of Rozena Stonefield.

Derald went home to ask his mother, Ethel McGlauchen, if they didn't have someone named Eldredge in the family. Ethel contacted her sister, Viola Harris, and word got around.46

The headline in the local paper read, "Local People Think They May Be Heirs to $100,000 Fortune," and the article outlined the family's dilemma. "Georgia Ann Eldredge left Milton when a young woman—'ran away from home'—and because of circumstances surrounding her going, it was considered more or less a disgrace and was never discussed in the family very much," stated the Milton Democrat. "However, it was learned that she eventually went to Alaska and was reported to be doing well. . . . There is a family of seven brothers and sisters who think they are nieces and nephews of this woman, although there is a slight difference in the spelling of the name."47

The only survivor from Georgia Anna's era was Nancy's brother-in-law, James "Ben" Daniels, who had helped her start her illustrious career. Ben was not an heir, but he was happy to testify on the qualifications of his nephew William Willis and his six brothers and sisters. And he was even happier to hear—after fifty years of wondering—that Georgia Anna had turned out well enough to force the rest of the family to admit they were related.