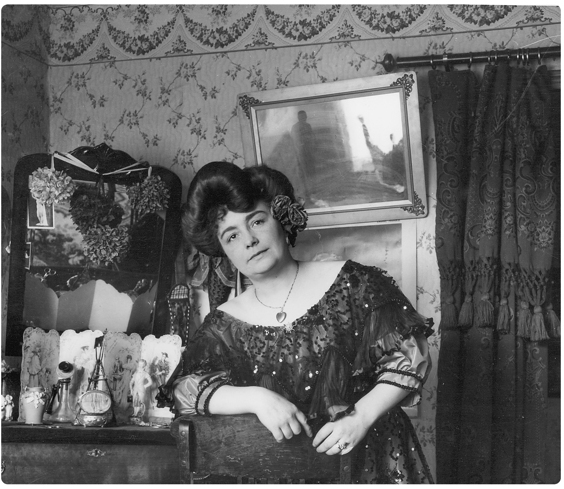

MADAM BURNET

In 1906 this veteran posed willingly for photographer in her small but lavishly decorated “crib” in the Fairbanks restricted district. Even though the subarctic gold camp was still being pioneered, prostitutes of the region dressed in expensive gowns and displayed astonishing social graces.

Michael Carey Collection

The red light district of Fairbanks, Alaska, was once hailed as the best in the West. In older cities farther south, patrons of houses of ill repute kept an eye on their wallets or lived to regret not doing so, but in the early gold rush town of Fairbanks there was no worry. A customer simply handed his gold poke to a lady of the evening, who took only what was fair and guarded the rest with her life. The honor of Fairbanks prostitutes was such that miners sometimes left gold with them for safekeeping. And many sporting women financed prospectors, playing a major part in developing this frontier.1

Fairbanks's restricted district was innovative in that its residents had a chance to buy the houses in which they worked—an option not generally afforded ladies of the night, almost universally the victims of rent gouging. The unusually progressive Fairbanks City Council also outlawed pimps,2 making it possible—perhaps for the first time under the American flag— for the average woman without wealth to become truly independent.

The Fairbanks Line, or "Row" as it was called early on, was established in 1906 during a continuation of the turn-of-the-century Klondike gold rush that attracted about 200,000 stampeders to the Far North.3 Ironically, the Line flowered, along with similar experiments in other frontier settlements like Dawson and Nome, during one of Western society's most zealous campaigns against prostitution. In what would later be called the Progressive Era (1900-1918), churchmen and reformers attacked the "Social Evil" with committee reports, surveys, studies, sweeping legislation, and police action.4 Yet despite national crusades to halt the sale of love, gold rush settlements throughout Alaska and Canada quietly experimented with quasi-legal red light districts with considerable success.

In the mid-1890s, outside the gold-rich northern territories, times were tough. Financial panics had paralyzed industry and thrown millions out of work. Coxey's Army of hungry and homeless had marched on Washington, D.C. There had been riots in Chicago railroad yards and protests in the Pennsylvania coal fields, but the depression was worldwide and enduring. So international headlines were made when, in July of 1897, two ships carrying the first of the successful Klondike miners (who took their moniker from the mispronounced Indian name of the Yukon River near Dawson) docked in Seattle and San Francisco with more than two tons of gold.

Stampeders flooded north: professional miners fresh from diggings in Australia and South America, hopeful amateurs from all over the world, Americans from every state. John Muir, a naturalist who knew well the hardships of the harsh subarctic region where the gold had been found, labeled them a "horde of fools," but there was more to this rush than dodging the depression or risking one's neck for money.

Richard O'Connor, who spent many hours with old Klondike hands, saw it as a dash for freedom. "Never before or since have so many American men had such a hell of a good time, without the perils of war, provided they stayed fairly healthy and had a fair amount of luck," he declared in High Jinks on the Klondike. "Back home they had been singing, 'There'll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,' but the Klondikers knew what a pallid falsehood that was,- the 'hot time' was to be found right where they were, far removed from Victorian restraint and the lavender delicacies of their womenfolk."5

With women agitating for suffrage and contesting the double standard whereby men were allowed to sow their "wild oats" while those of the "fairer sex" were considered ruined if they were sexually promiscuous, O'Connor suggested the mass migration north was a "flight from home, wife, and mother."

Not only were Alaska and the Yukon Territory isolated from polite society by thousands of miles and lack of timely communication, but they were also amazingly self-sufficient—not only gold-rich but boasting enough natural resources that men could live off the land if Dame Fortune failed to smile at their diggings. And although this was the largest gold rush in the history of North America, if not the world, the Far North's population remained so small that its moral lapses were of little concern to administrators in Washington, D.C., and Ottawa.

Even normally sober, conservative citizens were capable of squandering hundreds of dollars on wine, women, and song when caught up in the excitement of the remote gold rush communities.

". . . The problem is, without doubt, that an atmosphere of vice and of license exists in Dawson which amounts to contagion, and, under its influence, men [are] not really themselves," philosophized Mrs. La Belle Brooks-Vincent, a stampeding "businesswoman" (with an interesting police record) who penned a melodramatic history titled The Scarlet Life of Dawson and the Roseate Dawn of Nome. "Vice, in its overpower, exercises a hypnotic influence that paralyzes the judgment and neutralizes the more refined tastes. This is proved by the fact that some men do publicly in Dawson what they could not be induced to do privately outside. Steamers have stood at their wharves in Dawson, their decks disgraced by conduct on the part of departing passengers which the same persons would disavow outside. The same crowd would land in Seattle with utmost decorum."6

Given the fact that about 80 percent of the citizens of early gold rush settlements were male, it is not surprising prostitution was viewed as a "necessary evil." Obviously "wedded bliss" was not an option for everyone, and therefore could not provide much-needed sexual restraint in the face of such a heavy gender imbalance.

While those embracing "The Progressive Era" outside the territory blamed the "Social Evil" for America's moral decay, attempting to outlaw prostitution as a national menace,7 founding fathers in the Far North found legitimizing that institution a practical solution, not only to satisfy the natural lust of most citizens but to protect "respectable women" from the potential violence of a woman-hungry society.

Nor was there much opposition from the female contingent of those early frontier settlements. Most women observed the constraints of the late Victorian Era, which dictated that a whalebone corset, at least two ankle-length petticoats, and high-buttoned shoes were the uniform for proper feminine decorum, even while bucking high seas and struggling through icy mountain passes. But the emerging Women's Rights Movement was already proving effective. Many women had enjoyed freedom when left to fend for themselves during the Civil War. The Industrial Revolution made it possible (and mildly profitable) for women to work outside the home.8 The male domination of the Victorian Era was being challenged, and women of the Klondike gold rush challenged it just by being there, despite their conventional trappings.

Female motives for coming north were mixed, according to Klondike veteran O'Connor: ". . . some of them [were] intent on profit, others on sharing the risks of their men, still others gallantly determined to prove themselves as men's equals, few of these were eager to be placed on any sort of pedestal."9

Women rushed north for the same reasons men did, according to writer Frances Backhouse—because they were seeking wealth or adventure or both. While adventure was there for all who sought it, wealth was hard to come by. There were two approaches to making a Klondike fortune: mining gold or mining the miners. The first was less accessible to women because it required brute strength and because polite society disapproved of an unmarried woman staking claims, while a wife was expected to file in her husband's name.10

Therefore a large percentage of early female arrivals were either prostitutes or professional entertainers who supplemented their incomes through the trade. An 1899 police census of Dawson showed 3,659 men to 786 women. The town had dozens of dance halls and, while estimates are unreliable, about 400 prostitutes were thought to be working the area. Today's feminists question this high count, arguing that many more "respectable" women were among the stampeders than were given credit, but there could have been no less than 150 prostitutes early on, since that's how many the police assessed with mild fines during one single sweep of the Dawson red light district in 1898.11 Even that conservative count reflects a serious shortage of respectable women.

Nor did everyone within those hallowed ranks remain respectable for long. Some women were tempted by the unusually high wages of sin and the fact that few people back home would ever learn how their gold rush fortunes had been made. Others turned to prostitution out of necessity.

Jeremiah Lynch in his autobiography claimed cynically that "some women had a history and some not before they [came] but all had a history after arrival. There was no honest occupation for women. Many went professionally as housekeepers to miners who were rich enough to employ one, but it was only another name."12

However, one must look carefully at women's status in society at the turn of the last century to understand the desperation they must have felt when left on their own without resources. In many states the legal age of consent was ten years old, which allowed men to sexually exploit young girls. Business transactions, including purchasing property with money belonging to a wife, were automatically conducted in a husband's name. Considered the "weaker sex," females were discouraged from seeking higher education and generally excluded from lucrative jobs where they might compete with men. The Industrial Revolution only recently had made female independence possible, but those who sought it were paid inferior wages for horrendously long hours of dull, boring work. Studies done during the period indicate that while urban girls needed a minimum of eight dollars per week to live on their own, the minimum wage was only six dollars a week—and the gap was even wider in the Far North.13

In The Lost Sisterhood: Prostitution in America 1900-1981, Ruth Rosen warns, "When I look closely at the life stories of poor women during the early years of this century, I am struck again and again by most prostitutes' view of their work as 'easier' and less oppressive than other survival strategies they might have chosen. The statement that prostitution offered certain opportunities and advantages for some women, however, should not be interpreted as a positive or romanticized assessment of the life of a prostitute. Instead it should be read as an indication of the limited range of opportunities that early twentieth-century women faced in their daily struggle for economic, social and psychological well-being."14

Some single, respectable women did exceptionally well during the Klondike rush—women like Belinda Mulrooney, who made a fortune in the hotel trade and even more by investing in mining, Martha Black, who got her start running a successful sawmill, and numerous laundresses who scrubbed their way to small fortunes.15 But most female entrepreneurs had capital or male backers or both. Without support, it was almost impossible for a woman to survive on the straight and narrow.

Earning one's living by prostitution was dangerous, both mentally and physically, but the odds of survival for those who entered the trade during the Far North gold rushes were improved over years past. A harsh but reliable treatment for syphilis recently had been invented, and knowledge of birth control was improving. Many prostitutes in the North had the benefit of health inspections which, combined with the region's complete isolation for much of the year when the severe winters shut down easy transport, greatly simplified disease control. And most could count on police protection.

In addition to good money, prostitutes were given an edge in the Far North. "For a number of years during the earlier part of the Klondike and Nome excitement, such women were encountered everywhere. Since they always had plenty of money, the best accommodations on the steamers and in hotels were reserved for them," observed geologist Alfred Brooks, who traveled to all the stampedes. "This condition made it very trying for the better class of women to travel."16

And, while mainstream society condemned women of easy virtue, hordes of miners were more than grateful for their companionship or just a chance to watch them from afar. In one classic photo of a crowd waiting outside the Dawson post office, not a single female form can be spotted in a solid sea of men. Nor did conditions improve much in the decade that followed.

"I don't think I had ever seen so many men before. The dock was packed with them: tall, ruddy-faced, broad-shouldered men mostly, all of them young or in their early prime, and in every conceivable kind of costume," wrote Laura Berton, recalling her arrival at Dawson in 1907. "There were miners in mukluks and mackinaws, jumpers and parkas, surveyors in neat khaki togs, Englishmen in riding britches, police officers in immaculate blue and gold, police constables in the familiar Mountie scarlet, and on the edge of the throng clusters of Indians in beaded skin coats and moccasins. There were perhaps only a dozen women on the dock."17

Early prospectors were not anxious to bring their wives to virtually unexplored subarctic territory. Just getting to the Klondike was a formidable task, even for those who were fit. The overland route demanded more than thirty miles of hiking through mountain passes, then a 500-mile trip over lakes and down the Yukon in rafts, over two sets of fearsome rapids. Or stampeders could take the supposedly easier but more time-consuming and expensive 1,600-mile "all water" route to the Yukon River via St. Michael, Alaska, a long sea voyage under incredibly crowded conditions. Either way, women—then universally considered the weaker sex—were warned away, so strong motivation was a prerequisite for the trip.

"Girls were very scarce in that country, and if a man wanted to get married he took no chances with time," observed Anna DeGraf, who in 1894 pioneered Chilkoot Pass at age fifty-three in an unsuccessful search for her son, and later lived in all the major gold camps. "Even a woman past the heyday of youth was not exempt," she wrote. "It was that way all through Alaska and Yukon Territory. A girl would come in on a boat and sometimes be engaged, or even married, within a week. If she was not, it was not on account of lack of proposals."18

It may seem astonishing that so many women chose prostitution over the legitimate option of matrimony, until that choice is viewed in the realistic context of the era. "All too often, a woman had to choose from an array of dehumanizing alternatives," Ruth Rosen pointed out, "to sell her body in a loveless marriage contracted solely for economic protection, to sell her body for starvation wages as an unskilled worker, or to sell her body as a 'sporting woman.' Whatever choice, some form of prostitution was likely to be involved."19 And since only a small percentage of prospectors actually hit pay dirt, marriage was not usually the soundest economic option for women who had come north in search of wealth.

A few disgruntled gold rush participants gave Far North prostitutes short shrift. Retired stampeder E. C. Trelawney-Ansell bitterly insisted that "of all the predatory, gold-digging, disease-eaten, crooked female devils this side of hell, the worst were in the Klondike in the early days."20 Writer Cy Martin, echoing others he had researched, declared that "a Dawson City girl did not need good looks. She needed stamina, a cold, calculating eye, and utter ruthlessness."21

Yet James Wickersham, an Alaska district federal judge with a no-nonsense stance on crime, spoke surprisingly well of this group. "The sporting women were of a more robust class than usual among their kind, hence there were fewer cases of venereal disease among them," he wrote in Old Yukon. "The women were also younger, more vigorous and independent than those of the same class in the older, more crowded communities in the states. . . ."22

The best possible accounts of the good time girls and their lives would come from the women themselves, but such personal glimpses are extremely rare. As far as we know, only two prostitutes published accounts of their adventures in the Far North.23 The majority, however, had everything to gain from remaining anonymous and keeping their opinions to themselves.

What we do know about these women comes from census, cemetery, court, and police records, government reports, newspaper stories (which varied in accuracy and were too often prompted by publicity-seeking theater and dance hall performers), and personal accounts from those who claimed to have known them—most of whom virtuously denied all carnal knowledge.

As for the recollections of stampeders on which this book often relies, it must be remembered that most were recorded in later years when memories sometimes blur harshness with romance. However, one fact is certain: restricted districts flourished in the Far North for five decades. When they were finally closed, it was by the federal government, not by local vote. So it is safe to speculate that the gold stampeders' candid approach to prostitution worked well for the majority of citizens, who either backed or ignored the institution instead of campaigning against it.

Elmer John "Stroller" White, who lamented the passing of the era, best sized up its vitality in a column he wrote for the Whitehorse Star in 1912:

"The spirit of '98 is still extant all over the Yukon, but it takes more than three cents to the pan to awaken it. Back then good and reliable men, horny-handed sons of toil, many in moccasins, others in hob-nailed boots, would indulge in the 'long, juicy waltz' at three o'clock in the afternoon as readily as they would when the gloaming gloamed several hours later. Daylight next morning would find them promenading to the bar with more gusto than can now be found within the entire Klondike watershed to say nothing of Livingston and Kluane.

"Never again in the Yukon will dance halls advertise 'Fresh cheechako girls, just in over the ice.'"24