“I was skeptical when I started your training program, but I found that the challenging, but doable, three key run workouts caused me to get stronger and faster week after week.” That’s the most common refrain from readers who adhere to the FIRST training programs. The three-runs-per-week schedule defies conventional thinking about the necessity of piling on the miles.

Most runners who incorporate the three quality runs find that their fitness improves as do their race times. What explains this? Most runners focus on the frequency and duration of their training. Their conversations begin with “How many times did you run” and end with “How many miles did you log this week?” They neglect the importance of intensity—the pace of each workout. Try running the paces designated in the tables provided in this chapter and watch your race times improve.

While a certain fitness base is necessary, quality performances are determined more by intensity than by volume. Workouts that cause you to go really hard, recover, and go hard again have significant physiological benefits. Workouts sustained at a moderately hard effort for 20 to 30 minutes also train your body to exercise for long periods near your maximum effort. Doing long runs at speeds progressively closer to your marathon pace causes you to adapt to the stress of running hard for several hours to prepare for a marathon.

This chapter supplies you with the training paces appropriate for your current fitness level—paces that will lead to improvements in your fitness level and future running performances. It also provides the nuts-and-bolts descriptions for your three quality runs per week, the heart of the 3plus2 training program. You will find all of the details necessary for performing the three weekly quality runs. Following the breakdown of the overall design of the program are tables that show you how to determine your target time and pace for each run (see Tables 5.6, 5.7 and 5.8) and the training schedules for 5K, 10K, half-marathon and marathon races (see Tables 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.4, and 5.5). First, however, we present a brief discussion of the science underlying the FIRST program.

The theoretical concept underlying the FIRST training regimen is that each run be performed with a goal of improving one of the primary physiological processes and running performance variables. The training programs are designed to help runners train effectively and efficiently while avoiding overtraining and injury.

Maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) is a measure of the ability of an athlete to produce energy aerobically. One might say that maximal oxygen consumption gives a runner an idea of how large an engine he or she has to work with. Normally, a higher VO2 max indicates more work can be performed during a given time period. This simply means that an individual with a higher VO2 max should be able to run faster than an otherwise comparable runner with a lower VO2 max. A high maximal capacity to deliver oxygenated blood means there is the potential for more muscles to be active simultaneously during exercise. Values for VO2 max typically range between 40 and 80 milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of body weight. Research has shown VO2 max to increase as much as 20 percent through a combination of endurance and interval training. VO2 max and submaximal exercise capacity are limited by different mechanisms. VO2 max appears to be related more to cardiovascular factors, such as maximal cardiac output, whereas skeletal muscle metabolic factors, including respiratory enzyme activity, play more of a role in determining submaximal exercise capacity.

Lactate threshold (LT) is a measure of metabolic fitness. Lactate is an organic by-product of anaerobic metabolism, and its accumulation in the blood is used to evaluate the intensity that a runner can maintain for extended periods of time—usually 30 minutes or more. Lactate threshold and maximal steady state lactate levels are indications of how well one’s muscles are trained to do endurance-type work. Most people, except the most highly trained athletes, are limited by metabolic fitness rather than cardiovascular fitness. Highly trained endurance athletes become “centrally limited,” meaning they can work at extreme heart rates without severe muscle fatigue. An untrained individual might reach LT at about 50 to 60 percent of his or her maximum heart rate, whereas a well-trained runner won’t reach lactate threshold until about 80 to 95 percent of his or her maximum heart rate.

Running economy is the amount of oxygen being consumed relative to the runner’s body weight and the speed at which the runner is traveling. Unnecessary body motion results in an increase in oxygen consumption and thus a decrease in running economy. Running economy can be expressed either as the velocity achieved for a given rate of oxygen consumption or the VO2 needed to maintain a given running speed. Running at a given submaximal pace and using less oxygen indicate that a runner is more economical or has improved his or her running economy. This determinant of running performance generally takes the longest period of training for measurable improvements.

Training at the appropriate intensity is generally recognized as the most important factor for improving each of the three elements. For that reason, each workout needs to have the appropriate intensity, or running pace, that stimulates the physiological adaptation needed for improving.

Types of Training

| ELEMENTS | KEY RUN #1: TRACK REPEATS | KEY RUN #2: TEMPO RUN | KEY RUN #3: LONG RUN |

| Purpose | Improve VO2 max running speed, and running economy | Improve endurance by raising lactate threshold | Improve endurance by raising aerobic metabolism |

| Intensity | 5K race pace or slightly faster | Comfortably hard; 15 to 45 sec slower than 5K race pace | Approximately 30 sec slower than goal marathon pace |

| Duration of Each Run | 10 minutes or less | 20 to 45 min at tempo pace | 60 to 180 min |

| Frequency | Repeat shorter segments until quality work totals about 5K per session | One tempo run per week | One long run per week |

Warm up for 10 to 20 minutes of easy jogging followed by four 100-meter strides. Completion of the strides will make the initial track repeats much easier and reduce the shock of going from an easy warmup jog to a near all-out effort on the repeats. Stay comfortable with the strides and focus on good form. You shouldn’t be straining during the strides. Gradually accelerate for 80 meters until you reach approximately 90 percent of full speed, and then decelerate over the final 20 meters. Recover for 30 seconds or less and repeat.

In Chapter 13, two key drills that will help your form are described and illustrated on pages 179–182. These two key drills can be incorporated into your warmup strides. After completing two 100-meter strides, begin the third 100 meters by doing butt kicks for 20 meters and then gradually accelerating for 60 meters and decelerate for 20 meters. Recover for 30 seconds, begin the next 100 meters, and do high knee lifts for 20 meters, and then gradually accelerate for 60 meters and decelerate for 20 meters.

The track repeats include running relatively short distances of 400 meters to 2000 meters, interspersed with brief recovery intervals on a repeated basis. Track repeats are designed to improve maximal oxygen consumption, running economy, and speed. Most of these workouts total about 5000 meters of fast running per session. Including warmup and cooldown, Key Run #1 typically totals 5 to 6 miles or 8 to 10 kilometers.

Caution: Most runners can run the first few repeats faster than the specified target time. However, the challenge is to run the entire workout at the target time with little or no deviation in the times for each repeat. Also, the objective is not to run the repeats as fast as you can; you have two other key runs to perform for the week. Do not sacrifice meeting the target times for the tempo and long runs by running the repeats at an exhausting speed that does not provide sufficient recovery for Key Runs # 2 and #3.

After a challenging workout of repeats on the track, a cooldown is important. Jog slowly for 10 to 15 minutes.

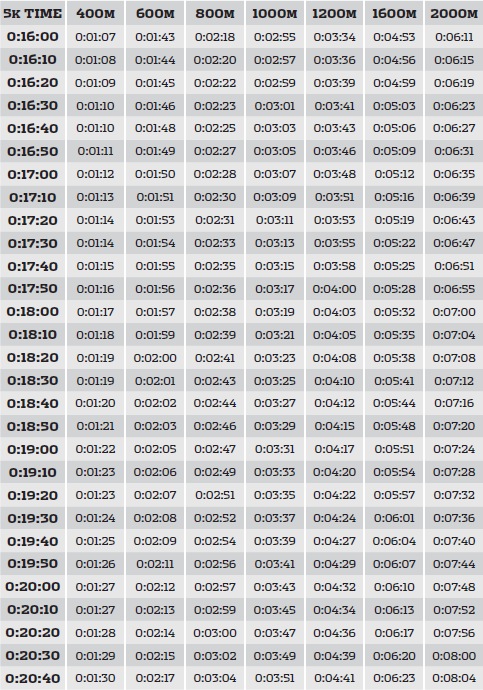

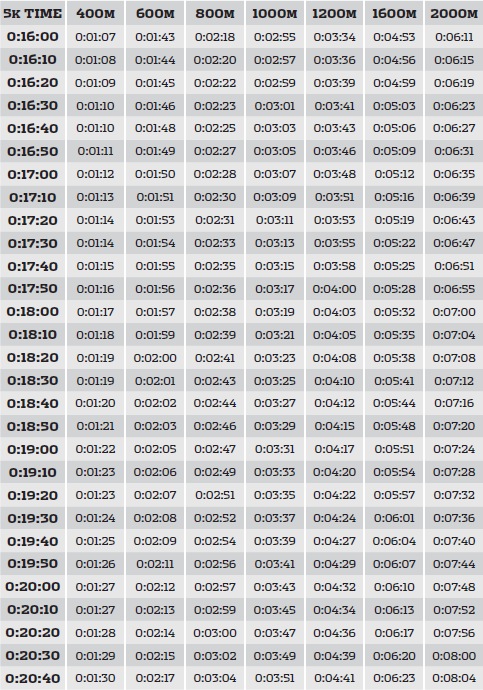

Repeat an 800-meter run six times, with a recovery interval (RI) of 90 seconds. In between the repeats, you recover by walking/jogging for 90 seconds. After the 90 seconds of recovery, you will start the next 800-meter run. You run all of the 800 meters at the same prescribed target time, which is found in Table 5.6. The goal of the workout is to keep a small range of times for the 800 meters. For example, rather than a set like 3:00, 2:58, 3:04, 3:08, 3:09, 3:02, shoot for a more consistent range of times, such as 3:02, 3:01, 3:02, 3:02, 3:03, 3:02. There should not be more than a couple of seconds’ difference in your times for the repeats.

Repeat runs of 1000 meters (2.5 times around a 400-meter track) five times with a 400-meter walk/jog as a recovery between repeat runs. Using your prescribed training pace for 1000 meters, try running the first repeat at the target time (found in Table 5.6). Check your time after finishing the first repeat to make sure you aren’t running too fast or too slowly. Jog 400 meters at a comfortable pace for your recovery (for most people, this lap will take 2 to 4 minutes). At the end of the jog recovery, begin the second repeat, concentrating on maintaining the prescribed pace. The times for running the five 1000-meter repeats should vary no more than a few seconds.

The FIRST training program emphasizes the importance of keeping a very small range of times for the entire workout. The target paces should be realistic and challenging, but not so difficult that you are unable to recover for Key Run #2. Our emphasis that the entire set of repeats be run within a range of only a couple of seconds pretty much ensures that you won’t overdo it.

Tempo runs begin with easy running for 1 or 2 miles prior to the faster tempo phase of the workout. As with the strides on the track, the pace should gradually increase during the easy miles, so that you are close to tempo pace by the end of the warmup.

The tempo portion of the workout is typically 3 to 5 miles at 10K pace or slightly slower. For marathon training, the tempo portion is extended to 8 to 10 miles at planned marathon pace.

A mile or 10 minutes of easy running is recommended for a cooldown after the tempo phase of the run.

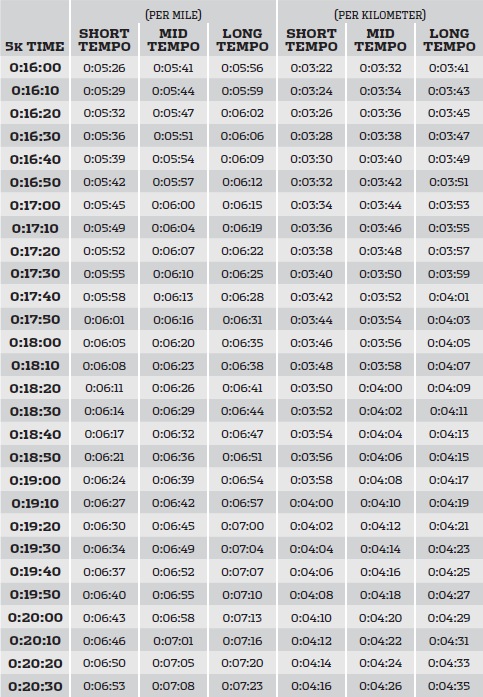

Start slowly and gradually pick up the pace, and after 1 mile, run the next 2 miles at the designated pace based on your 5K race pace (see Table 5.7). This short-tempo pace (ST) is approximately 15 seconds slower than your per-mile 5K race pace and 9 seconds slower than your per-kilometer pace. After the 2-mile tempo run, slow down and run an easy cooldown mile. In this example, Key Run #2 is a continuous 4-mile run.

While there is not a specific warmup for your long run, the early part of the long run can serve as the warmup. The recommended long run pace need not be achieved during the first couple of miles or kilometers.

The long run (relative to your goals and present training mileage) requires steady running from 6 to 20 miles at a pace equal to one’s 5K pace plus 45 seconds for the 5K and 10K long runs. For the half-marathon and marathon long runs, the long run pace is equal to one’s 5K pace plus 75 to 90 seconds, or 15 to 30 seconds per mile or 9 to 19 seconds per kilometer slower than planned marathon pace.

Try starting your training runs a bit slower than the prescribed pace and then pick up the pace in the middle section of your training run. Try to have a strong finish over the last couple of miles (kilometers) of your long training runs. If you run faster than recommended pace during the middle phase of the long run, it can offset the earlier slower pace so you can meet the average targeted pace for the entire run.

Ten minutes of easy walking after a long run serves as a good cooldown. Drinking a sports drink or recovery drink during these 10 minutes will aid your recovery (see Chapter 7). Doing some of the basic static stretches described in Chapter 13 is valuable.

Run 15 miles, 30 seconds per mile slower than planned marathon pace. For a runner with a target marathon time of 3:10, or 7:15/mile pace, this long run might begin with a 7:55 mile followed by a 7:40 mile before settling into a 7:45/mile pace. After 5 miles of running at a 7:45/mile pace, you may want to try the next 3 or 4 miles at 7:35-40 pace before running the last few miles at a 7:45/mile pace. Or you may want to hold the 7:45/ mile pace up through 12 miles and then try to run the last 3 miles faster. You can alternate strategies from one long training run to the next. The metric version of this workout is 24K at MP + 19. Run 24 kilometers 19 seconds per kilometer slower than planned marathon pace. For a runner with a target marathon time of 3:10 or 4:30/kilometer pace, this long run might begin with a 4:55 pace followed by a 4:45 kilometer before settling into a 4:49/kilometer pace. After 8 kilometers of running at a 4:49/kilometer pace, you may want to try the next 5 to 7 kilometers at a 4:40 to 4:45 pace before running the last few kilometers at a 4:49/kilometer pace. Or you may want to hold the 4:49/ kilometer pace up through 20K and then try to run the last 4K faster.

FIRST’S three key run schedules for distances of 5K, 10K, half-marathon, and marathon follow in Tables 5.1 through 5.5. To find the appropriate training target time or pace for a specific distance, refer to Tables 5.6 to 5.8. If you have not run a recent 5K, refer to the instructions on page 45.

5K Training Program: The Three Quality Runs

RI = Recovery Interval; which may be a timed recovery interval or a distance that you walk/jog.

Paces: ST = Short Tempo; MT = Mid-Tempo; LT = Long Tempo. See Table 5.7.

Key Run #1 (Track Repeats) begins with 10- to 20-minute warmup; ends with 10-minute cooldown.

See Table 5.6 for target times.

Key Run #2 (Tempo Run) begins with 1-mile (1.5K) warmup; ends with 1-mile (1.5K) cooldown.

See Table 5.7.

Metric equivalents appear in bold italics.

| WEEK | KEY RUN #1 (TRACK REPEATS) |

KEY RUN #2 (TEMPO RUN) |

KEY RUN #3 (LONG RUN) |

| 12 | 8 x 400 (400 RI) | 2 miles (3K) at ST | 5 miles (8K) at LT |

| 11 | 5 x 800 (400 RI) | 3 miles (5K) at ST | 6 miles (10K) at LT |

| 10 | 2 x 1600 (400 RI) 1 x 800 (400 RI) |

2 miles (3K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 2 miles (3K) at ST |

5 miles (8K) at LT |

| 9 | 400, 600, 800, 800, 600, 400 (400 RI) | 4 miles CS.5K) at MT | 6 miles (10K) at LT |

| 8 | 4 x 1000 (400 RI) | 3 miles (5K) at ST | 7 miles (11K) at LT |

| 7 | 1600, 1200, 800, 400 (400 RI) | 1 mile (1.5K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 1 mile (1.5K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 1 mile (1.5K) at ST |

6 miles (10K) at LT |

| 6 | 10 x 400 (90 sec RI) | 4 miles (6.5K) at MT | 8 miles (13K) at LT |

| 5 | 6 x 800 (90 sec RI) | 2 miles (3K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 2 miles (3K) at ST |

7 miles (11K) at LT |

| 4 | 4 x 1200 (400 RI) | 3 miles (5K) at ST | 7 miles (11K) at LT |

| 3 | 5 x 1000 (400 RI) | 2 miles (3K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 1 mile (1.5K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 2 miles (3K) at ST |

7 miles (11K) at LT |

| 2 | 3 x 1600 (400 RI) | 3 miles (5K) at ST | 6 miles (10K) at LT |

| 1 | 6 x 400 (60 sec RI) | 3 miles (5K) easy No additional warmup or cooldown |

5K Race |

10K Training Program: The Three Quality Runs

RI = Recovery Interval; which may be a timed recovery interval or a distance that you walk/jog.

Paces: ST = Short Tempo; MT = Mid-Tempo; LT = Long Tempo. See Table 5.7.

Key Run #1 (Track Repeats) begins with 10- to 20-minute warmup; ends with 10-minute cooldown. See Table 5.6 for target times.

Key Run #2 (Tempo Run) begins with 1-mile (1.5K) warmup; ends with 1-mile (1.5K) cooldown. See Table 5.7.

Metric equivalents appear in bold italics.

| WEEK | KEY RUN #1 (TRACK REPEATS) |

KEY RUN #2 (TEMPO RUN) |

KEY RUN #3 (LONG RUN) |

| 12 | 8 x 400 (400 RI) | 3 miles (5K) at ST | 6 miles (10K) at LT |

| 11 | 5 x 800 (400 RI) | 2 miles (3K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 2 miles (3K) at ST |

7 miles (11K) at LT |

| 10 | 2 x 1600 (400 RI); 1 x 800 (400 RI) |

4 miles (6.5K) at MT | 8 miles (13K) at LT |

| 9 | 400, 600, 800, 800, 600, 400 (400 RI) | 2 miles (3K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 1 mile (1.5K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 2 miles (3K) at ST |

9 miles (14K) at LT |

| 8 | 4 x 1000 (400 RI) | 4 miles (6.5K) at ST | 10 miles (16K) at LT |

| 7 | 1600, 1200, 800, 400 (400 RI) | 5 miles (8K) at MT | 8 miles (13K) at LT |

| 6 | 10 x 400 (90 sec RI) | 3 miles (6.5K) at ST | 10 miles (16K) at LT |

| 5 | 6 x 800 (90 sec RI) | 1 mile (1.5K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 2 miles (3K) at ST 1 mile (1.5K) easy 1 mile (1.5K) at ST |

8 miles (13K) at LT |

| 4 | 4 x 1200 (400 RI) | 3 miles (5K) at ST | 10 miles (16K) at LT |

| 3 | 5 x 1000 (400 RI) | 6 miles (10K) at MT | 8 miles (13K) at LT |

| 2 | 3 x 1600 (400 RI) | 3 miles (5K) at ST | 7 miles (11K) at LT |

| 1 | 6 x 400 (60 sec RI) | 3 miles (5K) easy No additional warmup or cooldown |

10K Race |

Half-Marathon Training Program: The Three Quality Runs

RI = Recovery Interval; which may be a timed recovery interval or a distance that you walk/jog.

Paces: HMP = Half Marathon Pace; ST = Short Tempo; MT = Mid-Tempo; LT = Long Tempo. A plus sign (+) followed by a figure indicates seconds per mile or kilometer. See Tables 5.7–5.8.

Key Run #1 (Track Repeats) begins with 10- to 20-minute warmup; ends with 10-minute cooldown. See Table 5.6 for target times.

Metric equivalents appear in bold italics.

Table 5.4

Novice Marathon Training Program: The Three Quality Runs

RI = Recovery Interval; which may be a timed recovery interval or a distance that you walk/jog.

Paces: HMP = Half-Marathon Pace; ST = Short Tempo; MT = Mid-Tempo; LT = Long Tempo. A plus sign (+) followed by a figure indicates seconds per mile or kilometer. See Tables 5.7–5.8.

Key Run #1 (Track Repeats) begins with 10- to 20-minute warmup; ends with 10-minute cooldown. See Table 5.6 for target times.

Metric equivalents appear in bold italics.

Marathon Training Program: The Three Quality Runs

RI = Recovery Interval; which may be a timed recovery interval or a distance that you walk/jog.

Paces: HMP = Half-Marathon Pace; ST = Short Tempo; MT = Mid-Tempo; LT = Long Tempo. A plus sign (+) followed by a figure indicates seconds per mile or kilometer. See Tables 5.7–5.8.

Key Run #1 begins with 10- to 20-minute warmup; ends with 10-minute cooldown. See Table 5.6 for target times.

Metric equivalents appear in bold italics.

Key Run #1 (Track Repeats) Target Times

(improves economy, running speed, and VO2max)

Key Run #2 (Tempo Run) Paces

(improves lactate tolerance)

Table 5.8

Key Run #3 (Long Run) Paces

(improves skeletal and cardiac muscle adaptation)

Q. When can I start the FIRST training program?

A. We recommend a base training of 15 miles per week for 3 months prior to beginning any of the FIRST programs; the base training for the marathon training program should be closer to 25 miles per week. In addition to the requisite weekly miles, runners must be capable of long runs of 5 miles for the 5K program, 6 miles for the 10K, 8 miles for the half-marathon and novice marathon, and 15 miles for the marathon training program. If you are a beginning runner, see Chapter 3.

Q. I have never done this type of training. How do I get started?

A. During the base training, gradually become familiar with the track repeats and tempo runs. By introducing just one of the faster-paced workouts at a time, you can avoid too great a training overload at one time. During the base training, these faster-paced workouts do not have to be run at a pace as fast as prescribed by FIRST for the training program. Use the 3-month base training to gradually work up to your FIRST training paces.

Q. Can I use my goal race times to determine my training paces?

A. It is important that training paces be determined from actual race time performances, which represent the runner’s current fitness level. It needs to be emphasized that you should run the paces based on your current fitness level and not your goal race times. To do otherwise may increase your risk of a running-related injury.

We have coached runners who insist on trying to run training paces consistent with their goal race times rather than those determined from recent race performances, which reflect your fitness level. When runners try to maintain their ambitious training paces over several workouts, they run into problems. They may be able to do it for Key Run #1 and, perhaps, even Key Run #2, but then fall apart in Key Run #3. In Chapter 10, we address running-related injuries due to overly ambitious training paces.

Q. How important is it to stick to the prescribed paces?

A. Very important. Running more slowly will not provide the stimulation necessary for adaptation; running faster will jeopardize your chances of successful completion of the next key workout. Furthermore, too fast a pace can lead to overtraining and possible injury.

Q. When should I adjust the paces for faster workouts?

A. You can adjust after running a race that produces a new standard or after you complete all three weekly workouts at the specified paces and feel less than challenged. If either the race time indicates a faster training pace or if all three weekly workout times are easily achieved, then a faster pace should be attempted for the next week’s workouts.

Q. Why are there different recovery intervals?

A. The workouts are designed to have a variety of distances and paces. Similarly, the recovery times for repeats are varied. The reason for training at different distances and intensities is that the body adapts when it is pressed to respond to an overload. Different types of overload elicit different physiological responses. The workouts are designed to stimulate the key physiological mechanisms needed for improved running performance. Recovery periods can increase or decrease the stress of the workouts. Varying the stressors—distance, pace, and recovery period—is a mechanism for producing changes in the workload and stimulating physiological adaptations.

Q. How important is a warmup and cooldown?

A. Your likelihood for achieving your target paces in your workouts will be enhanced with a proper warmup. The ideal warmup includes some dynamic stretching and a gradual intensity increase in your warmup running. A cooldown will help to keep you from being stiff and sore later.

Q. What if I don’t have a track for Key Run #1?

A. Runners who don’t have a track for the repeats designated in Key Run #1 have several options. Find a flat section of road or path that has good footing and is safe for intense running. Measure and mark 400 meters. That will enable you to do most of the workouts. The paved areas around the perimeters of superstore parking lots often provide the needed distance. Another option is to use a GPS to measure the distance run. It can be programmed for distance or time. (See “How to Use a GPS Watch for FIRST Training” later in this chapter.)

Q. Can I run more than three times per week?

A. We have conducted training studies that permitted runners to supplement our basic program with additional runs if they wished. What we found is that most runners chose not to do extra runs after the first few weeks because they found that they could perform the three key workouts better with a day of recovery between workouts. There were no differences in the improvement of those who ran only three days per week compared to those who did supplemental easy runs. For that reason, we designed the 3plus2 program to include the three quality runs and two cross-training workouts. An optional cross-training workout is also permitted.

Most programs include running 5 to 7 days per week and running more than three times per week. But for reasons stated throughout this book, we find that much can be accomplished by running three times per week without the accompanying risks of injury.

The FIRST training program doesn’t restrict runners to only three runs per week, but any additional runs must not interfere with achieving the target paces of the three key runs. We have had runners report that they were successful by coupling one or two additional runs with the three key runs prescribed by FIRST. As stated before, FIRST recommends coupling cross-training workouts with the three Key Runs so as to reduce the likelihood of injury and to provide more quality cardiorespiratory training.

Q. Isn’t the FIRST 3plus2 training program low on total training miles?

A. There are many differences in individuals’ abilities to tolerate training mileage. These differences are influenced by physiology, anatomy, biomechanics, and years of running experience. Typically, smaller, lighter, and younger runners are able to tolerate more miles. These runners become the elite performers who can run hard, run often, and run long. However, many runners, in particular, aging runners, find that they cannot tolerate high mileage weeks built on 5 to 7 days of running. For them, reducing the number of running days per week is appealing and effective. Runners who have limited time for training, are injured, or who are just looking for a fresh approach to training may find that our program can help them achieve faster performances while fitting their training into a balanced lifestyle. Because the FIRST program is lower on training miles than other traditional running programs, it is attractive to those in the aforementioned categories. However, the FIRST 3plus2 training program is NOT lower on training volume. A portion of the weekly total of aerobic training is achieved from aerobic modes of training other than running.

For a ballpark estimate of the number of equivalent miles you add to your training volume with cross-training, divide your total number of cross-training minutes by the average pace—number of minutes per mile or kilometer—you would normally maintain on a run for the number of run-equivalent miles or kilometers. For example, you normally do a 5-mile run at an 8:00/mile pace, but today you did 40 minutes of stationary biking at a comparable level of perceived exertion, then those 40 minutes of biking would equal 5 equivalent miles toward your weekly total training volume.

Q. Will the low mileage program enable me to meet my running goals?

A. Not only is it our belief, but also it is borne out by our own experiences and those of the runners we have trained and the many runners who have followed the FIRST training program that by Training with Purpose runners can achieve the high level of fitness necessary to improve running performances. These three runs will require devoting only 3 to 5 hours per week to running. The three sessions per week of high quality running still provide the runner with the fitness benefits of high intensity training and the stimulation, physiological and psychological, associated with hard efforts.

Q. Will my fitness improve more with distance or intensity (speed)?

A. Training volume and intensity are both critical factors in improving fitness. Runners often find it challenging to find the right balance of volume and intensity. If you run a lot of miles each week, it becomes difficult to run at a pace fast enough to stimulate the physiological adaptations needed to get faster. If you run very fast for each run, it is difficult to get the total mileage necessary for building endurance. That’s why FIRST has designed and incorporates three key run workouts with different distances and paces to develop a balance of endurance and speed.

Q. How does hill training fit into the 3plus2 training program?

A. The FIRST training program emphasizes the importance of maintaining the proper pace for all key workouts. We understand that the pace for a tempo run and long run will be affected by hills. More time will be lost on the uphills than gained on the downhills, but the two should even out roughly on an out-and-back or loop course. There is no easy rule for adjusting pace times for hills since the steepness, total elevation gain, etc., would have to be calculated.

Try to simulate race course terrain with your training course, if possible. If your planned race is on a hilly course, then train by using hills in longer runs as well as tempo runs. If you live in a flat area you can treat bridges, overpasses, and parking decks as hills to incorporate hill training into your training. Hills certainly add stress to your training. That stress can make you a stronger runner.

Learning to run hills economically takes practice. Obviously, it is tough to run your target paces over rolling, hilly courses. While your average pace over the distance of your run should be near to your target pace, you won’t be running a constant pace, but you should be running at a constant effort. Your effort up and down hills should be the same. That means you will run slower than target pace up and faster than target pace down. You need to remain focused on the downhill sections of your running, which is where runners tend to relax. Staying focused on your effort for the duration and distance of your tempo and long runs will translate well to race day.

Stress from hills not only taxes the cardiorespiratory system, it also stresses the muscles and connective tissue. Plantar fasciitis and Achilles tendinitis can develop from excessive hill running. Be sure to stretch the calves before and after hill running. If like a lot of runners you have tight calves, you might need to limit the amount of time spent going up and down.

If you are headed to Boston in April, be sure to include hill training in your preparation. Be prepared to run several miles uphill after miles of long, gradual downhill running that fatigues the quads.

Q. Why is the longest marathon training run only 20 miles?

A. There is no definitive study or theory for determining the optimal distance for the marathon long training run. I know runners who have run very good marathons with no run longer than 15 miles and runners who like to do at least one over distance (>26 miles) long run. Most marathon programs recommend long runs of 20 miles. Running farther than 20 miles makes it difficult to recover, thus interrupting one’s training program. Where the threshold is located that stimulates adaptation and improvement versus the threshold that leads to prolonged fatigue is a mystery. I am sure that it differs by individual, especially with the training pace of the individual. Consider that a 2:40 marathoner will complete a 20-mile training run in a little over 2 hours while a 5:00 marathoner will take 4 hours. Their recoveries from those efforts will be quite different.

We know that most marathoners stick to the 20-mile distance and are able to run excellent races with that preparation. FIRST recommends 20 miles as the longest training run because it is difficult to have a high quality training run (meaning it is difficult to maintain a pace close to marathon pace) at a distance greater than 20 miles. So to run farther than 20 miles most likely will mean that you are running more slowly.

Q. Is it better to run 20 miles near marathon pace or run farther at a slower pace?

A. The FIRST training program is based on pace, and our training philosophy is based on intensity. Intensity is the variable that contributes most to fitness. Thus, we prefer a long run that is faster than what most other programs recommend. That is the most distinctive feature in our training program, along with running fewer days per week with potential additional runs replaced with cross-training.

Q. Why does FIRST recommend five long training runs of 20 miles?

A. Many runners ask, “Why so many?” Others, “Why so few?” There’s nothing magical about five or any other number. We have had runners qualify for Boston with only one 20-mile run using our novice marathon program. There is no one training program that is ideal for everyone. However, in general, our experience in both running and coaching is that it’s the long runs that best prepare you for the marathon. Too many long runs and your legs become fatigued, too few and you aren’t trained to handle the race day pace for the distance. We think five 20-mile runs over 15 weeks provide a good preparation.

Q. Is it okay to enter a race and do my training run?

A. Runners enjoy taking part in races, and so they often ask if it’s okay to run one at the target training pace. If the race distance is shorter than their designated training run distance, they say that they will run some additional miles before or after the race. If the race is longer than their designated training run distance, they say that they will drop out once that distance has been completed. In theory, these strategies should work. In practice, they frequently fail to happen as proposed. Too often the runners write after the race that they were feeling good, the pace felt easy, and that they were pulled along by the crowd and finished the race much faster than the targeted training pace or, in the case of the race being longer than their designated training distance, they were feeling good and decided not to drop out. Too often the targeted race and the preparation for it are undermined by using a race for training.

Q. I had a bad training run. What happened?

A. Runners who are following the FIRST training program typically see their fitness improve and their training times get faster. After several weeks of improvement, they write us frantic over a poor training run—much slower than usual, or perhaps they weren’t able to complete it. It is common to have a bad run, as it is common to have a bad day. Why? We don’t always know, but work, sleep, nutrition, cumulative fatigue, weather, and the unknown are among the factors. Accept it as part of the training cycle and don’t worry about it. It happens to everyone.

Q. What am I to do if I miss a workout? A whole week? Multiple weeks?

A. Do not be concerned about a missed workout, nor should you try to squeeze it in later. Stay on schedule with the next workout and don’t risk interfering with it. In particular, it’s not a problem if you missed the workout because of your personal schedule. It becomes more complicated if you missed a workout because of injury. That’s addressed in a later chapter about injuries.

If you miss a week of training, it’s typically not a problem, either. Over 16 weeks you aren’t going to lose your fitness with missing a week. Again, continue with the schedule as if you had completed that missed week’s training.

If you miss 2 or more weeks of training, you need to reconsider your targeted race and determine if your goal should be redirected to another race. It somewhat depends on when those 2 weeks were missed and why. If they were missed in the first 4 weeks of the training program, and you were reasonably fit when you began it, you can most likely continue with the program without concern. If you missed the 2 weeks in the middle or near the completion of the training program, you will need to assess how much fitness was lost. More important is what you were doing those 2 weeks. That is, if you were doing serious cross-training and staying fit that’s one thing, but if you were on a cruise just chillin’ and likely to have gained several pounds, that’s a very different situation. I have heard from folks who reported both of the last two scenarios and my advice was quite different. The former was told to continue with the training program and the latter was told to pick another race as a goal.

Q. Does FIRST recommend training with a heart-rate monitor?

A. FIRST does not use heart rate as a gauge of intensity for its key running workouts. We prefer using pace as a determinant of intensity. Heart rate fluctuations are caused by a variety of variables and do not reflect running speed. A few of those variables, but not an exhaustive list, include body position, core temperature, hydration, emotions, time of day, amount of sleep, recovery status, nutritional status, and medications.

During a long run at a steady pace, your heart rate will increase initially and then level off as the oxygen requirement of the activity is met. However, prolonged exercise at a constant intensity places an increasing load on the heart. Although the metabolic demands of the exercise do not increase, there is a progressive decrease in venous return of blood to the heart. So if venous return drops, there is less blood in the heart and stroke volume (the volume of blood pumped from one ventricle of the heart with each beat) therefore drops. Your heart rate increases to compensate for the reduced stroke volume. The resulting decreased stroke volume and the accompanying increase in heart rate are referred to as cardiovascular drift. This drift is generally due to decreased plasma volume caused by sweating. Thus, if you are maintaining a constant heart rate during that long run, you will gradually run more slowly throughout the run. That won’t prepare you to run a constant pace in your next race.

Q. Can FIRST Key Runs be performed on a treadmill?

A. Yes. Many runners do Key Runs #1 and #2 on the treadmill. Most report doing so because they need to run early in the morning or late at night and prefer not to run in the dark. Running in the dark increases the likelihood of an accidental injury, especially if the ground is covered with snow and ice. Beyond reducing the likelihood of an accidental injury, running on the treadmill probably provides a better cardiorespiratory workout than a slower, cautious run on a slick outside surface. In summer, runners from the South report doing their workouts on the treadmill in an air-conditioned space rather than running slowly in extreme heat and humidity.

Our research shows that the oxygen and energy costs for running at the same speed are the same running on the treadmill as compared to running on the road. The treadmill does not need to be adjusted with elevation as long as the treadmill is calibrated accurately. That cannot be assumed. We find that belts on treadmills become loose and do not always travel at the speed that is displayed on the monitor. Runners often contact us for help in translating speed in miles-per-hour to minutes-per-mile. For that reason, we have provided a table in Appendix A that provides those equivalencies.

Q. How do I choose my race pace?

A. For the half-marathon and marathon, your training program designates your HMP (half-marathon pace) and MP (marathon pace) from Table 5.8. That’s your race pace. If during the 16-week training program you are able to do all three key runs without pushing yourself, you should use a faster 5K reference time for selecting your training targets and paces from Tables 5.6, 5.7 and 5.8. That will result in a faster HMP and MP, which determine your target half-marathon and marathon target finish times. For the 5K schedules, your target race finish time is determined by your 5K reference time used for selecting training targets and paces. For the 10K target race finish time, refer to Table 2.1 and find the 10K time comparable to your 5K reference time.

Q. What training pace adjustments need to be made at elevation?

A. While the oxygen content of the atmosphere is at a constant percentage (20.9 percent), at higher elevations the atmospheric pressure decreases, reducing the partial pressure of oxygen, which makes less oxygen available for the runner. Endurance activities are hampered at higher elevations beginning at around 3,000 feet. The extent of the performance reduction depends on the distance of the event and to the extent that the individual is acclimatized. The effects of elevation are greater on longer distances. At 5,000 feet, expect a 3.5 percent reduction in performance in a 10K; at 7,500 feet, expect a 6.3 percent reduction in performance in a 10K.

We received a message from three women in Santa Fe, New Mexico, an elevation of 7,000 feet, asking how they could use the FIRST training program for a 3:30 marathon. I knew that they could not expect to run FIRST’s target paces designated for the 3:30 marathon, so I suggested that they use the training paces for a 3:38 marathon and that having trained at those paces at elevation, they could run a 3:30 at sea level. All three achieved their 3:30 goals.

GPS-enabled watches are replacing the traditional chronograph long worn by runners. Runners have been asking us for several years if the FIRST training program is available for their Garmin, the most popular GPS for runners. Fortunately for them, there is Dr. Butch Hill, an electrical engineering professor at Ohio University. Butch is a longtime FIRST training program user. He generously offered to respond to FIRST requests for sharing the Garmin programming for the FIRST key runs. For several years, we have forwarded him those requests. He agreed to provide the following instructions for this edition, so that they are widely available:

Runners of almost any ability can use a Garmin Forerunner effectively for the key runs, because explicit paces and distances for every workout are set in the workout plans and pace tables. The design of the Forerunner employs a similar approach: paces are set in customized “speed zones,” and separately entered workouts use those speed zones. When you enter the workouts you can specify the length of each workout element, the target zone for that element, and the rest intervals. There are other workout devices offering similar capabilities, but my familiarity is with the Forerunner.

It is fairly straightforward to set up the FIRST key runs using a Forerunner, together with Garmin’s Training Center software. Set your speed zones as specified in Table 5.9, then program the appropriate rest and workout distances.

There are multiple benefits to using a Forerunner for your workouts. You don’t need a track to do the workouts, and all your running data are automatically recorded. Once you learn which beeping tone means “speed up,” “slow down,” and “stop,” you don’t have to even look at the device during your workout. But there are minor drawbacks, too. There’s the temptation to keep looking at the display to see how well you’re doing (thereby assuring that you will not do as well as you could, as running with your wrist in front of your face doesn’t help your form). Batteries can die in the middle of a workout (for those who forget to recharge), or the Forerunner can suddenly lose its GPS fix. Losing the fix can be especially irritating because the device will then assume that you’re not moving and hound you to speed up, even if you’re going all out! I have an older model and understand that the newer models are less likely to lose the GPS fix.

Table 5.9 gives an overview of the appropriate “My Activities” settings in Garmin Training Center for use with the key runs. Make sure that you set the activity to “Running” for Key Run #1 and to “Biking” or “Other” for half-marathon or marathon training, respectively. You are strongly urged to change the names of the paces from the Garmin defaults to the key run names (e.g., change “Snail,” “Turtle,” etc., to “Easy,” “MP + 60,” etc.). For Key Runs #2 and #3, you will have to add a few seconds to the paces given in Tables 5.7 and 5.8 for the “Lower Limit,” and add a few seconds to those paces for the “Upper Limit.”

Key Run #1 paces will require one additional step: the times given in Table 5.6 are for the given distances, not paces in minutes/mile or minutes/kilometer. For example, if your 400M time is 0:01:30 in this table, your pace per mile, which is 1609 meters, would be (1609 meters ÷ 400m) times 1:30, or 6:02/mile. You could therefore set your lower limit for Speed Zone 10 to 6:05 and your upper limit to 6:00. Some of your speed zones may overlap, particularly if you’re a fast runner: the Forerunner doesn’t seem to care. If you are using your Forerunner in metric mode, then you simply need to adjust the pace to that of 1000M. For example, the 400M time would convert to (1000 ÷ 400) times 1:30 or 2.5 x 1:30 = 3:45 per kilometer.

The speed zones have been chosen so that speed increases with zone number. This can be useful for those occasions when your Garmin keeps signaling you to speed up or slow down. As you run, the Forerunner will display the name of the speed zone that you’re in. Assuming that you’ve followed our suggestion to give the speed zones meaningful names, if you’re supposed to be running at 1600-meter pace, but the display says “400M,” you know that you’re going much too hard.

If you program the distances and rest intervals manually, rather than use the programs available online, you’ll need to follow the directions in the Garmin Training Center program; see “Creating a New Workout.”

Table 5.9

Garmin Speed Zone Settings for Key Runs

| GARMIN SPEED ZONE | KEY RUN #1 (ALL) & #2 & #3 (5K & 10K) ACTIVITY: RUNNING |

KEY RUN #2 & #3 (HALF-MARATHON) ACTIVITY: BIKING |

KEY RUN #2 & #3 (MARATHON) ACTIVITY: BIKING |

| 1 | LT* | Easy | |

| 2 | MT* | MP + 60 | |

| 3 | ST* | MP + 45 | |

| 4 | 2000M | Easy | MP + 30 |

| 5 | 1600M | HMP + 30 | MP + 20 |

| 6 | 1200M | HMP + 20 | MP + 15 |

| 7 | 1000M | HMP | LT |

| 8 | 800M | LT | MP |

| 9 | 600M | MT | MT |

| 10 | 400M | ST | ST |

* Marathoners and half-marathoners do not need to enter the LT (Long Tempo), MT (Mid-Tempo) and ST (Short Tempo) paces here unless they would also sometimes follow the 5K or 10K training plans.

Dear FIRST team,

I wanted to write to thank you for the research that you’ve put into the Run Less, Run Faster training plan and to let you know that I had a very successful marathon following the plan. Yesterday, I ran a PR of 2:57:49 in the Milwaukee Lakefront Marathon. That bests my previous PR (3:02:55) by more than 5 minutes (in 2003) when I was 27 years old. I’m now 36 and hadn’t run a marathon in almost 5 years, but I really wanted to break the 3-hour barrier at least once in my life. I followed the training regimen laid out in the book, missing only a few key runs because of fatigue or a minor injury. I used my bicycle commute to work as the cross-training exercise by modifying my commuting route so I could minimize stopping and match the tempo suggested in the cross-training workouts.

I think the strengthening exercises and drills were a critical element in this program that I haven’t incorporated in the past. I held up better in the training and the last miles of the race than I have previously because I was a stronger runner.

Thank you again for doing this research and writing the book.

Sincerely,

Justin Marthaler

Network Administrator

Madison, Wisconsin

Dear Sirs,

Just a quick note to let you know how delighted I am with your marathon training program. I have been following it since the beginning of this year with the aim of qualifying for Boston. That meant achieving a time of under 3:35 given that I am now 50. My previous best time was 3:42 in Athens in November 2009 (admittedly that was uphill all the way). Other than that, most of my marathons were completed in about or just under 4 hours.

My plan was to get a qualifying time for Boston today at the Rotterdam Marathon, which is over a flat course and has a reputation for being quite fast. In fact, I got my qualifying time 12 weeks into the program in Barcelona with a 3:33, but went ahead and did Rotterdam in 3:30:54!

So, thank you very much for designing a wonderfully successful training program.

Xavier Lewis

Director, Legal and Executive Affairs, EFTA Surveillance Authority

Brussels, Belgium