1.1 LUIS BARRIOS (LEFT) AND IMPRISONED DEPORTEE (PHOTO: DAVID BROTHERTON).

1.2 DAVID BROTHERTON (LEFT) AND JUAN, A DEPORTEE (PHOTO: WILLIAM COSSOLIAS).

IN ITS OVERT and covert existential meanings and its descriptions of the microworlds of the deportee and the macrostructures of daily life, we can identify in Pedro’s letter (see Introduction) the major conceptual themes of our analysis: the punitive turn in the criminal justice system that overdetermines immigration policy; the traumatic experience of social and cultural exclusion that the French sociologist Sayad (2004) calls the “suffering of the immigrant”; and the efforts of subjects to come to terms with their new roles and identities as deportees. These areas will be carefully developed throughout the remainder of the book. But first, how did this project come about? What are its aims? How does the literature guide our study and contribute to our analysis? How did we collect our data (primarily interviews and observations) from some of the most stigmatized members of our society? And finally, what does the rest of the book look like?

This project occurred quite accidentally. As is the case with much research, it happened through serendipity. In our previous work we focused on the political transformation of New York City street subcultures into what we called “street organizations” (Brotherton and Barrios 2004). During our research we found that a substantial part of the groups’ memberships was composed of first- or second-generation Dominicans. In 1998, after delivering an address on youth deviance among the Dominican immigrant community in New York at a criminological conference in Santo Domingo, we were asked during the question-and-answer session to talk about the increasing phenomenon of Dominican youth with gang affiliations returning to their country after being deported from the United States. At the time, we had little to say on the matter; however, we agreed that this would be an important topic for future investigations, and we vowed to start following this process from cities such as New York, Boston, and Miami.

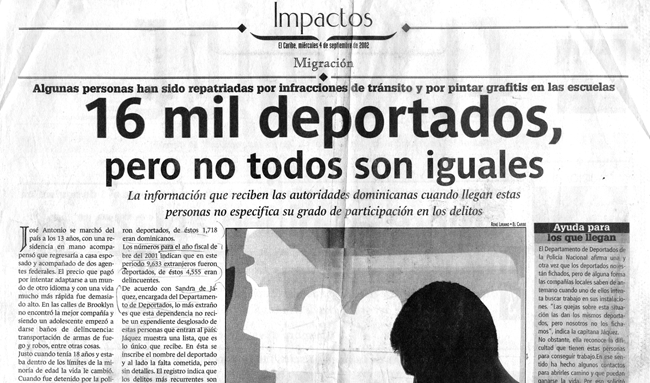

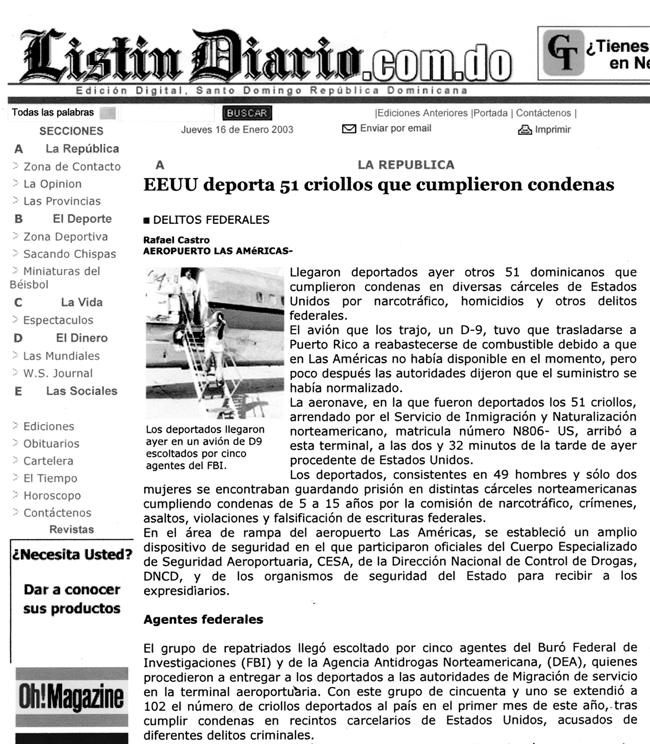

Four years later, in September 2002, we kept our promise, and the first author, David Brotherton, began a year-long sabbatical in Santo Domingo. By that time, we had completed some informational interviews with Dominican lawyers and community organizers in New York City and observed that, although the phenomenon of Dominican deportees was growing rapidly in the wake of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, there was little community organization or media coverage around this issue. In Santo Domingo, the opposite was the case. Articles in major daily newspapers such as el Listin Diario, el Nacion, and el Caribe were being published almost weekly. These articles focused on how new deportees were arriving at the capital’s airport and often noted that serious felons, including murderers, rapists, armed robbers, and drug dealers, were among them. Some reports also highlighted the tragedy of deportations with reference to family separation and the difficulties of reintegration while warning of the demonization of deportees.

The second pathway into this subject was through the life experience of the second author, Luis Barrios. Barrios has long been connected to the Dominican community through marriage, political activism, and his predominantly Latino congregations (first in the South Bronx, then in Central Harlem, and now in Washington Heights) to whom he has been ministering for the past twenty years as an ordained priest in the Episcopal Diocese of New York and the United Church of Christ. Barrios’s spiritual work drew him to the deportee issue by involving him in the struggles of family members to prevent fathers, mothers, husbands, sons, and daughters from being deported and in the plight of deportees who have illegally returned to live in the city’s “shadows” (Chavez 1997).

Consequently, as researchers committed to the community and its concerns, we wanted to know more about this emerging subpopulation that was traveling in the opposite direction of the Third World to First World flows conventionally imagined in immigration studies. A host of questions came to mind: What were the characteristics, contexts, dynamics, social networks, and historical roots of this population? How does this population occupy and develop within a transnational space? Why was this process of emigration, immigration, and repatriation occurring now? Although the phenomenon of deportees was largely a product of state-sponsored sanctions (Zilberg 2006), how were local communities responding to these exiled populations? Do deportees succeed in creating new networks, subcultures, and organizations to fill the gaps in social support and solidarity? What happens to the self-identity of deportees as they adjust to their new life-worlds? And finally, how do we articulate the pathos of social rejection or the resourcefulness in the mentalities of resistance?

To answer such questions, we had to get as close as possible to the everyday life experiences of deportees, to observe them, engage them, listen to them, and learn from their memories of the past, the narratives of their present, and their strategies for dealing with the future. To do so, we chose the methods of critical ethnography, an approach used in our previous study on street gangs, in which we emphasized the following:

Our orientation begins from the premise that all social and cultural phenomena emerge out of tensions between the agents and interests of those who seek to control everyday life and those who have little option but to resist this relationship of domination. This . . . approach . . . seeks to uncover the processes by which seemingly normative relationships are contingent upon structured inequalities and reproduced by rituals, rules and a range of symbolic systems. Our approach . . . is an holistic one, collecting and analyzing multiple types of data and maintaining an openness to modes of analysis that cut across disciplinary turfs.

We have chosen a collaborative mode of inquiry. . . . By this we mean the establishment of a mutually respectful and trusting relationship with a community or a collective of individuals which: (i) will lead to empirical data that humanizes the subjects, (ii) can potentially contribute to social reform and social justice, and (iii) can create the conditions for a dialogical relationship between the investigator(s) and the respondents.

(BROTHERTON AND BARRIOS 2004:4)

Toward the end of this chapter we will describe in more methodological detail what we managed to accomplish. Before doing so, let us briefly discuss the literature that illuminated our way.

What does “the literature” have to say about the 30,000–50,0001 Dominicans deported during the last twelve years (1996–2008), many of whom were legal residents, and the current rate of deportations, which is nearly three hundred per month? How does the literature deal with the sociological contexts in which these policies emerge? What about the racial, class (Johnson 2009), ethnocentric (Cashdan 2001), and gendered (Boris 1995) nature of such policies as upwards of 50,000 legal residents are forcibly repatriated from the United States to cities and villages throughout the Caribbean and Latin America every year? Unfortunately, the literature does not say a great deal, but the following is a brief summary of what we have found in both the social scientific and journalistic literature along with some of the theories that can best explain this extraordinary phenomenon.

The focus on the dynamics behind deportations and the lived experiences of deported populations from the United States has only recently been the subject of serious social scientific inquiry in the English-language literature. Hitherto, only six articles (Griffin 2002; Lonegan 2008; Morawetz 2000; Noguera 1999; Precil 1999; Zilberg 2002) and three books (Brotherton and Kretsedemas 2008; Coutin 2007; Kanstroom 2007)2 have appeared that discuss the general and specific political, legal, economic, cultural, and criminological causes behind the expulsion of so many Caribbean, Mexican, and Central American legal and nonlegal residents from the United States during the 1990s.

Noguera (1999) argues that increases in the rates of deportation have coincided with changes in the population flows to the United States, particularly from the Caribbean, in the latter part of the century, as large numbers of working- and lower-class urban and rural immigrants were drawn to the United States by its demand for cheap labor. Such immigrants are vulnerable to labor market fluctuations, are easily exploited and victimized, and have little cultural capital to pass on to their children. The resulting combination of poverty, low social mobility, the lure of the informal economy, and the unprecedented expansion of the social control industry have effectively criminalized entire African American and Latino communities, an effect reflected in the race/ethnic distribution of both state and federal prison populations (particularly in states such as New York, California, and Texas). Thus, the increasing arrest rates among immigrants of color combined with drastic changes to immigration laws have inevitably given rise to mass detentions and expulsions, among which Dominicans rank prominently (see also Ojito 1998; Rohter 1997; Lonegan 2008).

Meanwhile, Precil (1999) placed the issue of Haitian deportees in the broader context of the increased expulsions of other Latino and Caribbean populations. Precil argues that this persecuted population has arisen largely in the wake of the U.S. Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 and has functioned to relieve the overcrowding of U.S. prisons at the expense of increasing instability in the receiving countries. In the earlier work of Griffin (2002), the author uses the notion of “geonarcotics,” a concept linking drugs, geography, power, and politics, to analyze the phenomenon of deportation. For Griffin, the problem is the combined result of changes occurring in other social and political domains such as (i) “get tough” antidrug efforts by federal and state governments, (ii) new legislative oversight on immigration, (iii) increased resource allocation to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, (iv) restrictions on discretionary relief from deportations for foreign nationals, (v) congressional initiatives on “administrative removal” procedures, and (vi) early release programs that grant parole to some inmates in exchange for immediate deportation. Another study by Zilberg (2002), based on field work in Los Angeles and San Salvador, focuses on the transnational processes behind the deportee gang member phenomenon and what the removal of this contemporary “folk devil” means for the construction of urban social spaces, state social controls, community identities, and the politics of simultaneity (see also Smith 2000). Meanwhile, Coutin (2007), focusing on populations from the same geographical area, asks what the consequences of legal categories such as “citizen,” “alien,” and “deportee” are for immigrant subjects whose “multiple realities” in a globalized world frequently render borders meaningless.

Other research worthy of note include studies of expelled Salvadoran, Belizean, and Mexican gang members and Haitian “delinquents.” The first, completed by social scientists at the University of Central America, El Salvador (Santacruz Giralt and Cruz Alas 2001), looked at the levels of social cohesion and violence of gang members returning from California. The authors found that many deportees had been socialized into violence as children, spanning both El Salvador’s civil war and the intergroup violence in the streets and barrios of Southern California. In a second study on the recent wave of Mexicans drawn to New York City, Smith (2005) discusses the lived realities of transnationalism, describing how returning Mexican gang members have affected the local youth culture by changing notions of public space and bringing new forms of subcultural violence to the community. These findings are echoed in a third study on the Garifuna ethnic community of Belize, many of whom migrated to Los Angeles and who now watch their children being transported back to their native country as urban gang members (Matthei and Smith 1998). Finally, DeCesare (1998) provides an in-depth journalistic report on the hyperalienation experienced by expelled Haitian youths who neither know the Haitain culture nor its language, Creole.

The substantive literature on Dominican deportees reveals many of the same themes as deportees in other countries. We have written on the everyday lives of deportees in Santo Domingo, citing the massive increase in deportees since the passing of the U.S. Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRAIRA) of 1996, their health problems, levels of drug addiction, struggles with indigence, and efforts to organize (Brotherton 2008; Brotherton and Barrios 2009). Gerson (2004) similarly raised the growing issue of drug abuse among deportees—especially heroin (see also Martín 2010)—the interlocking U.S. systems of criminal justice and immigration, and the collateral effects on the families left behind. This latter theme is taken up by Brotherton (2008), who has described the trauma of appeals processes in the United States for Dominicans and their families and the vindictive, irrational nature of deportee policy in its present form.3

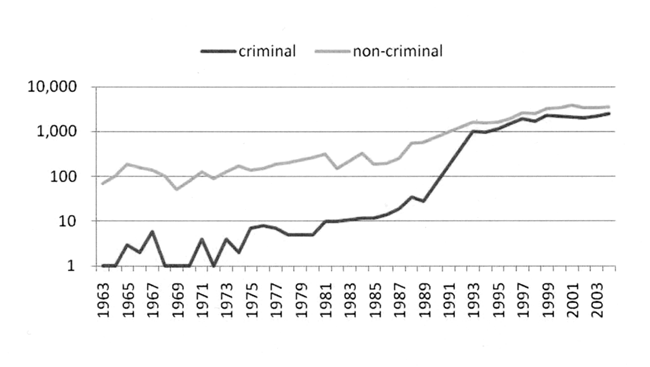

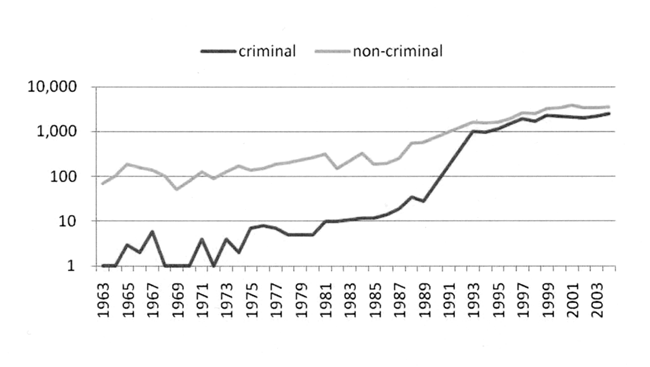

In summary, the substantive, mostly empirical literature on deportees offer the following findings: (i) cultural estrangement and stigmatization are rampant among deportees; (ii) deportees experience high levels of direct (i.e., interpersonal) and indirect violence (i.e., the denial of basic material and social needs that allow human beings to become self-actualized [see Salmi 1993; Maslow 1954]) prior to their expulsion; (iii) the transnational social and (sub)cultural strategies and practices of some deportees that might find their origins in the United States include gang membership, drug use, involvement in criminal enterprises, and the establishment of self-help groups; (iv) U.S. immigration/deportation policy has become increasingly restrictive and draconian due to the passing of three acts: the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, the Immigration Act of 1990, and the IIRAIRA of 1996 (see graph in figure 1.3). Immigration and deportation policies have in turn been heavily influenced by the war on drugs (especially the Anti-Drug Abuse Act in 1988, which introduced the term “aggravated felony”) and the war on terrorism (particularly through the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 and the Patriot Act of 2001); and (v) deportation policies wreak enormous collateral damage on both U.S. families and communities as well as on the communities of the receiving nations (Baum et al. 2010).4

1.3 FOLLOWING THE ENACTMENT OF THE IIRAIRA IN 1996, THE NUMBER OF DOMINICANS DEPORTED FOR NONCRIMINAL OFFENSES INCREASED EXPONENTIALLY. ALTHOUGH THE OVERALL NUMBER OF DEPORTEES HAD INCREASED EARLIER, THE INCREASE IN THE DEPORTATION OF INDIVIDUALS WHO COMMITTED NONCRIMINAL OFFENSES OCCURRED DURING THE PERIOD THAT THE DOMINICAN GOVERNMENT BEGAN TO REGISTER AND MONITOR DEPORTEES FROM THE UNITED STATES. THE DOMINICAN GOVERNMENT CURRENTLY DOES NOT DISTINGUISH BETWEEN DEPORTEES REPATRIATED FOR COMMITTING CRIMINAL AND NONCRIMINAL OFFENSES (VENATOR-SANTIAGO, UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT, 19).

1.4 AN ARTICLE FROM THE LEADING DOMINICAN NEWSPAPER LISTIN DIARIO (APRIL 9, 2002) READS, “SIXTEEN THOUSAND DEPORTEES, BUT THEY ARE NOT ALL THE SAME: THE INFORMATION THAT DOMINICAN AUTHORITIES RECEIVE WHEN THESE PERSONS ARRIVE DOES NOT SPECIFY THEIR LEVEL OF PARTICIPATION IN THE CRIMES.”

1.5 ANOTHER ARTICLE FROM LISTIN DIARIO (ONLINE EDITION; JANUARY 4, 2003) READS: “51 DOMINICANS HAVING COMPLETED THEIR PRISON SENTENCES DEPORTED FROM THE UNITED STATES.”

To theoretically frame these experiences and analyze their meanings in broader terms, we need to isolate the literature that provides the best signposts for our data. There is, of course, an enormous body of literature on immigration and migration studies (see inter alia Cordero-Guzman et al. 2001; Hirschman et al. 1999; Foner and Fredrickson 2004), and we have no intention of embarking on a long review of these areas that are best left to more seasoned scholars of the subject. However, the theories we are most interested in are those that pertain to social control and the immigrant because we are, after all, dealing primarily with the subject of social exclusion. To this end we have divided our review into four discursive domains: social control paradigms and the U.S. immigrant, assimilationism and its critics, segmented assimilation and transnationalism, and crime control and resistance.

These bodies of literature, when brought together, provide a “constitutive criminology,” or a criminology that draws on multiple theoretical traditions to explain historically contingent criminal or deviant phenomena. The late modern emergence of the deportee as a sometimes free, sometimes incarcerated, yet always highly stigmatized subject that currently makes up 25 percent of all U.S. federal inmates is an instructive case in point.

SOCIAL CONTROL AND THE IMMIGRANT

The theory of social control was a peculiarly “American” social scientific project at the beginning of the twentieth century (Melossi 2004), based on beliefs about consensual democracy in the wake of authoritarian regimes in Europe and influenced by theories of Spencerist evolutionary development and Durkheim’s notion of anomie. It is important to emphasize that the notion of social control was always intertwined with the notion of social change, especially given the rapid social, economic, and cultural transformation of the United States. Behind the notion of social control was the philosophically pragmatic premise that human beings are in their nature adaptive creatures and will find ways to coexist with their specific environments. As Melossi explains:

The concept of social control . . . encapsulated within the Chicago School of Sociology and Pragmatism—the only genuinely “American” philosophical orientation. It was a concept of social control that was all-pervasive because it responded to the need of the new society to incorporate large masses of newcomers in its midst, on grounds of a factual cooperation rather than through the traditional authoritarian instruments of politics and the law.

(MELOSSI 2004:35)

The paradigm of social control had very much to do with how American society would effectively deal with the immigrant phenomenon and has come to be defined as the capacity of a social organization to regulate itself; the opposite of this paradigm was and is “coercive control, that is, the social organization of a society which rests predominantly and essentially on force—the threat and use of force” (Janowitz 1978:84). This narrative about integrative socialization (the inculcation of norms and values that leads to a consensus) and social processes was widely promulgated by early social scientists, such as Park (1961), Burgess (1921), Wirth (1928), and Thomas and Znaniecki (1927), who shaped criminological and sociological approaches to immigration issues for decades to come. Park, in particular, described immigration and settlement as a process of ordered segmentation, as newcomers were expected to pass through several universal stages of competition, conflict, accommodation, and, finally, assimilation.

Perhaps the highest empirical expression of the Parkian paradigm was Wirth’s (1928) The Ghetto, in which he described two waves of Jewish immigration, showing that despite the problems of social and cultural displacement, immigrants through their self-organization and willingness to adapt over generations found mobility in the flexible, expanding, and pluralistic metropolis. Thomas and Znaniecki found both similar and different processes in their study of Polish peasants; their two-volume work is an optimistic narrative about the processes of immigrant adaptability. Nonetheless, they clearly state that this process cannot be achieved without enormous costs to the community as it endures stages of disorganization due to cultural conflict and reorganization.

Thus, although social control was one side of the adaptational equation, social disorganization was the other, and through much of the last century this social contradiction has been continually invoked to describe the emergence of gangs, crime, and delinquency in largely immigrant and migrant neighborhoods (see Thrasher 1927; Shaw and Mackay 1942; Cloward and Ohlin 1960). Importantly, for the Chicago School, although the emphasis in social relations was on the voluntaristic, resilient nature of the immigrant subject in civil society, it was always imagined within a broader ecological context, albeit with sometimes unexpected outcomes for the social order.5 Nonetheless, the notion that immigrants accused of criminal offenses would be removed en masse from society is not present in any of this early literature.

WHAT ABOUT ASSIMILATION?

The Chicago concept of social control and the immigrant was largely a humanistic and optimistic one and did not foresee the time when hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of subjects would be socially excluded across borders or incarcerated in internal gulags. Until the 1950s, most sociologists adhered to the view that there were few, if any, structural constraints or contradictions that could undermine their belief in the progressive American century. In fact, the immigrant was proof of America’s openness, social mobility, possibility, and “pragmatism”; it was evidence of a natural process of global selection as well as the New World’s seductiveness.

These narratives of America’s voluntaristic openness and the effectiveness of the natural evolutionary processes of assimilation (see particularly Warner and Strole 1945) shifted markedly in the 1950s with the more unified and functionalist notion of social systems developed by Parsons at Harvard and then by Lazarsfeld and Merton at Columbia. In this era, social science veered strongly towards homus economicus in terms of its scientific methodology and away from the more open-ended, naturalistic inquiries of Chicago. Little was left to chance, as social policy took its cue from sociological systems-based paradigms involving schooling, the family, the university, law, the factory, and the criminal justice system. In this heyday of social engineering, the narrative of the U.S. immigrant, especially any authentic, resilient one, was sidelined by the pretensions of and presumptions about American social, economic, and technological progress.

Oscar Handlin’s 1951 book The Uprooted was one of the last of these optimistic narratives on settlement, arguing that immigrants would assimilate into U.S. society without contradictions or countervailing tendencies. However, a decade later, a different reading of the immigrant’s social and cultural voyage was offered by Oscar Lewis (1965) in his widely read La Vida. In Lewis’s work, the socially committed anthropologist offered detailed observations of the everyday colonized life worlds of Puerto Ricans in New York City and in San Juan, Puerto Rico, elucidating the lack of mobility of this population and their self-destructive behaviors—behaviors that, as he reasoned, constituted a culture of poverty. Although his descriptions of everyday family life were meant to show the situated culture of a transmigrant community reacting to the marginalizing pressures of “free-enterprise, pre-welfare state stage capitalism” (quoted in Bourgois 2002), the theoretical weakness of his culturalist argument and the psychological reductionism used in his analysis have overshadowed critical contributions to the immigration debate contained in his work.6 As Bourgois (2002) argued, we cannot deny the very real suffering experienced by urban, inner city residents, including immigrants, for fear of essentializing urban poverty. Lewis exposed the deep, intergenerational social injuries being inflicted on a vulnerable immigrant population that ran counter to much of the literature and still seems to be a difficult subject to embrace, both theoretically as well as empirically.

SEGMENTED ASSIMILATION AND THE COMING OF TRANSNATIONAL SOCIETY

The governing concept of assimilationism in both immigration and race relations studies was fundamentally shaken by the rebellion in the streets of the United States during the race and ethnic revolts of the 1960s. As a result, new academic departments, with very different visions of the immigration project, were established throughout the academy. Nonetheless, although segregation and institutional discrimination were definitely prominent features of urban immigrant life, there were still wide swaths of the American population that were passing from their immigrant to their ethnic stages of social integration, which meant that some kind of assimilation was taking place and needed to be better represented and theorized (see Alba and Nee 1999). Addressing this conundrum, Portes and Zhou (1993; see also Portes and Rumbaut 2001) developed the notion of “segmented assimilation,” bringing together several models of the integration process in U.S. society with a strong emphasis on the intersection of social and economic capital; they saw the possibility that significant cohorts of second-generation immigrants might find themselves excluded on a more permanent basis and therefore downwardly mobile. In a classic summary of their position, the two researchers described the three models as follows:

The first replicates the time honored portrayal of growing acculturation and parallel integration into the white middle-class; a second leads straight in the opposite direction to permanent poverty and assimilation into the underclass; still a third associates rapid economic development with deliberate preservation of the immigrant community’s values and tight solidarity.

(PORTES AND ZHOU 1993:82)

Still, there were problems with the immigration model despite these theoretical advances. First, how do we understand an “underclass” assimilationism without taking into account neocolonial and global postindustrial processes (Gans 1992)? Second, what was the historical and cumulative role of the state in processes of social exclusion and its part in increasing punitive legislation against the immigrant (see Zolberg 2008; Ngai 2004)? Third, the “interstitial” zones of urban areas were still presented as “black boxes” with few empirical studies to explain the dialectical processes of both inclusion and exclusion that must always be part of the immigrant/outsider narrative (see Young 1999, 2007).

One way to address these critiques is through the theoretical contributions of researchers working in the field of transnationalism. In their efforts to describe and theorize the increasing percentage of humankind residing permanently within, between, and across cultures, states, and societies, researchers such as Basch et al. (1994), Guarnizo (1994), and Smith (2005) have described relationships and tensions that emerge between the global webs of macrostructures and the flows and movements of people driven to cross or circumvent borders, building counter-hegemonic or new sociocultural spaces as they do so. Out of this discourse has emerged a focus on the existence of multicultural or hybrid populations that have been described by Robert Smith as “embodied in identities and social structures that help form the life world of immigrants or their children . . . constructed in relations between people, institutions and places” (Smith 2005:7).

Of particular interest to us in this literature is the work of Michael Peter Smith (2000), who takes to task those who bring to our attention the changing forms of domination prompted by global capitalism but omit from consideration the actions and consciousnesses of the ordinary citizens and noncitizens that allow such structures to function. For Smith, an essential ingredient of transnationalism is its focus on the way global society is constituted not above our heads but through our everyday efforts to make sense of the world—to create meaning through processes of accommodation, assimilation, resistance, and contestation. As such, he lists five tenets of transnationalism that are particularly relevant to our study:

1. Global structures are made and they can be unmade—the logics of capital formation are not a given but must be worked out, implemented, and produced. Such logics, therefore, do not represent a totalizing force.

2. The urban community is the key site for investigating the processes of transnationalism. It is a transnational locale in a world of migrations, expulsions, flexible capital accumulation, and political simultaneity (e.g., the mimicking of criminal justice policies such as “zero tolerance across borders” that are most notable [see Zilberg 2004]).

3. The culture that is produced by the intersection of transnational structures and agencies must be documented to understand the precise nature of accommodations, assimilations, and resistances.

4. All action is historically situated but is not locked into a periodized framework of analysis such as “postmodernity” and other epochal narratives. To overemphasize the period detracts from the peculiarities of the contemporary and its transitional, contingent, and unfinished nature.

5. The global and the local must not be made into a binary opposition; rather, they are interconnected spaces, places, and processes that conceptually and empirically help us better understand the construction of space, identities, and “place-making.”

Strangely, despite the wide-ranging discourses in immigration and transnational studies, rarely do such discussions venture into the territory of criminology (Martinez and Valenzuela 2006; Rumbaut 2006). This is unfortunate because so much of the early sociology of immigration laid the groundwork for studies of crime, whereas so many contemporary immigrant communities are the subject of increasing penetration by the state into all spheres of daily life.7

SOCIAL EXCLUSION, CRIME CONTROL, AND THE CONTRADICTIONS OF LATE MODERNITY

By casting for terrorists using every tool at its disposal—most notably immigration and criminal law enforcement—and then selectively detaining and deporting non-U.S. citizens for typically minor immigration or criminal law violations, immigration law socially controls immigrant communities through the deportation threat. Imposing this threat, or that of detention pending deportation with no consideration of individual merits, is a highly effective instrument of social control.

(MILLER 2005:27)

Miller, a judicial scholar, highlights the use of an array of criminal justice and immigration laws and their apparatuses to socially control immigrant communities. This observation accords with the work of Young (1999, 2007), who argues that state threats against immigrants are a particular form of othering in late modern capitalism, a process of circumscribing or thwarting social citizenship that he describes as bulimic rather than just exclusionary. In Young’s words:

None of this is to suggest that considerable forces of exclusion do not occur but the process is not that of a society of simple exclusion which I originally posited. Rather it is one where both inclusion and exclusion occur concurrently—a bulimic society where massive cultural inclusion is accompanied by systematic structural exclusion. It is a society which has both strong centrifugal and centripetal currents: it absorbs and it rejects.

(YOUNG 2007:32)

Young is referring to the tendency of advanced capitalist societies, particularly Britain and the United States, to culturally include yet socially exclude large sections of the population, particularly those from the lower classes and so-called “minorities.” This highly contradictory process is carried out through several intersecting dynamics: (i) the pushes and pulls of the political economy with its restructuring of work, redistribution of wealth, irrational reward system, and heightening of class divisions; (ii) the universalism of consumer culture and its promotion of need, individualism, and freedom; (iii) the technological revolution of information generation and dissemination; (iv) the evolution of the social control industry with its rapid expansion of gulags, laws, surveillance systems, and constraints on civil and democratic liberties; and (v) the porous and fluid nature of all physical, social, and cultural borders. Together, these processes make it difficult for individuals to formulate a coherent sense of self and lead to a ubiquitous condition that he calls “ontological insecurity.”

In this process of bulimia, Young (along with legal and criminal justice scholars such as Welch [2002], Simon [2007], Kanstroom [2007], and Kurzman [2008], and sociologists such as Bauman [2004]) cite the radical shift of society during the 1980s toward what has been described as a “new penology” (Feeley and Simon 1992) and a “culture of control (Garland 2002) based on a set of beliefs about the pathological nature of criminals and other types of socially constructed human pollutants. In this brave new world of governance through crime and fear, there is a presumed need to take preemptive action and exact extreme punishments to ensure that risks to the good, the pure, and the healthy (Douglas 1966) never materialize. Kanstroom (2007) and Kurzman (2008) in particular show the impact on the deportee of three conjoining wars: the war on drugs, the war on terrorism, and the war on immigration. Welch (2001) adds that the moral panics used to mediate, rationalize, and frame these strategies reflect the needs of an industry of crime control (Christie 1993) in which the deportee has become a source of revenue and an object of financial desire on the part of multinational corporations specializing in security.

But what of resistance? Is it all such one-way traffic? Theoretically it is critical to locate agency in these chaotic and contradictory processes and not to relinquish social and political will to the obsessions with order (Bauman 2004). Therefore, we seek a language to consider the many acts of individual and collective defiance performed by immigrants who are not simply adaptive and acculturating creatures (see, in particular, the critical anthropological work of De Genova [2005] on Mexican immigrants in Chicago and the critical theological work of Barrios [2010, 2008, 2007a]).

What takes immigrants over the border in such numbers? Is it simply the lure of the American Dream? What lies behind the sacrifices of family and friends as tens of thousands of dollars are spent on trying to reunite spouses with their children despite the massive indebtedness incurred? Who have the will and intellect to defend themselves against a criminal justice system that has consistently denied subjects information and adequate legal representation and has kept them isolated from any form of social support (see Pedro’s letter in the Introduction)? How is a culture or subculture formed among the stigmatized? And how is life lived, engaged, and enjoyed rather than endured? Such questions all speak to the other side of the deportee experience and to what Katz (1988) calls that transcendental emotional quality in acts of deviance or what Ferrell and Hamm (1998) and Lyng (2004) might see as the existential “edge” that subjects reach for, knowing that they will cross the border or emerge intact from their heroin high. To guide us toward the answers, aside from those cited above, we have found the vibrant field of cultural criminology with its pointed criticism of the atheoretical positivism that dominates academic crime talk particularly stimulating (see Ferrell et al. 2008; Hamm 2007), while we have consistently referred to the fertile resistance discourses developed by Gregory (2007), whose work in the Dominican Republic focuses precisely on the relationship between dependency, the informal economy, and social citizenship.

According to the literature, much about the deportee population remains an enigma, and this is particularly true of the Dominican deportee. We know little of any profundity about either the criminal or noncriminal biographies of its members, its genesis, and its evolution as a heavily labeled population, or its sociocultural interface with current Dominican society.

Such research is, by its nature, transnational, which means that we needed to design a project that could access data reflecting the cultural fluidity of the subjects while also examining the more fixed locations from which they are currently speaking. Clearly, such research is not logistically easy to accomplish; consequently, we had to devise a project that had one central field site, the Dominican Republic capital Santo Domingo (where most Dominican deportees now reside), and a secondary field site, New York City (from which most of them are deported). Four different stages of data collection constituted our ethnographic approach, as we endeavored to accomplish one of the first transnational ethnographies of the deportee.

STAGE ONE: SETTING UP THE FIELD SITE

To gain access to such data, perspectives, and processes, especially in this somewhat occluded transnational space (Smith 2005; Glick-Schiller et al. 1998), required entering into the life worlds (Habermas 2001; Katz 2003) of subjects that are quintessentially “hidden” or “hard-to-reach” (Morgan 1996). In September 2002, the first author, Brotherton, set up the Santo Domingo field site in the Dominican Republic and started to make contacts with other qualitative researchers who might have direct or tangential relations with this population. Through such contacts, Brotherton developed a relationship with José, a deportee from New York City who worked as a street hustler and tour guide (see chapter 9), and Manolo, another deportee who was and still is a tour guide. Both José and Manolo, thus, became our first key informants and were paid 100 pesos (approximately $3.50) for each successful interview (15 in all) in addition to 100 pesos paid to each interviewee.

STAGE TWO: EXPANDING THE INFORMANT BASE

In January 2003, in conjunction with members of the faculty at the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD), we organized the first-ever conference on deportees in the Caribbean. The event attracted more than 300 participants, including 40 deportees, 5 of whom broke their silence and spoke out publicly about their experiences of being deported. These relationships led to a purposive sample of 35 deported men (25 interviews in Spanish and 10 in English), ranging in age from 21 to 52 years old, and 5 deported women. We used the format of face-to-face, life-history interviews to elicit narratives that were descriptive, self-reflective, and highly phenomenological (Behar 1993; Katz 2003) and that provided us with nuanced and detailed insights into the historical, social, economic, emotional, and cultural nature of the deportation experience.

These subjects resided in different working-class and poor barrios in Santo Domingo, including the Zona Colonial, Villa Duarte, Villa Mella, Capotillo, San Carlos, Cristo Rey, and 27 Febrero. The interviews were carried out in a range of settings, including respondents’ houses, a key informant’s house and office, park benches, cafes, UASD, and barrio churches. In addition to the deportees, Brotherton interviewed a range of social actors involved directly in the lives of returned deportees, including priests, academics, law enforcement personnel, U.S. embassy and Dominican government officials, and Dominican journalists.

As in our previous research with street subcultures, from the outset we pursued a methodology that has been termed “collaborative” (see Moore 1978; Brotherton and Barrios 2004), which ensures the active participation of subjects in the research act. This was accomplished through the two informants helping us develop our interview questionnaire, suggesting different strategies to engage and develop rapports with the subjects, and constantly informing us of the changing dynamics of barrio and street life.

1.6 FATHER ROGELIO CRUZ AT A POLITICAL RALLY (PHOTO: LUIS BARRIOS).

STAGE THREE: INCARCERATED DEPORTEES AND THE YOLAS 8 TO PUERTO RICO

Stage three consisted primarily of face-to-face interviews with deportee inmates in two Dominican prisons and a visit to Nagua, a small coastal town on the northern side of the country, from which many immigrants attempt to sail to Puerto Rico in boats known as yolas. In Nagua, we made contact with a well-known priest and advocate of the deportees, Father Rogelio Cruz, who acted as an intermediary and provided us with important information on the scale of the exodus. We completed fifteen interviews in this locale with nonurban participants (ten men and five women).

STAGE FOUR: INSIDE THE LEGAL PROCESS OF DEPORTATION

In this penultimate stage of the research process, Brotherton participated in the appeals of eight Dominican deportees as an “expert witness,” observing the courtroom interactions in which subjects were making their last bids to remain in the United States (see Brotherton 2008). Most of these events took place in a federal court building in Manhattan, but some occurred in penitentiaries outside New York City. This research yielded both field observations and multiple informal interviews with immigration lawyers and deportees’ family members.

These multiple sources of data form the bases of our analysis and have enabled us to document with empathy and cultural sensitivity the lives of subjects who once immigrated to a country where most of them assumed they would remain for the rest of their lives but from which they have now been permanently banned.

Finally, it should be mentioned that this story is told by two researchers who themselves are personally familiar with the journey of the immigrant. The first author, Brotherton, immigrated to the United States from Britain more than twenty years ago and spent a year as an undocumented alien in California before becoming “legal” and entering graduate school. The second author, Barrios, a native of Puerto Rico, was first brought to the Lower East Side of New York City as a five year old by his mother, who at the time was seeking refuge for herself and her eight children from the domestic violence of her husband.

STAGE FIVE: RETURNED DEPORTEES IN NEW YORK CITY

The fifth stage of the data collection was performed by Luis Barrios, who, through his “insider” contacts within the Dominican community, interviewed eighteen deportees who had returned illegally to the United States. Barrios’s task was to elicit data that focused on the strategies of survival for such a vulnerable population, the mode of reentry, and the processes by which subjects developed the psychological and material resources to make this journey.

Here we describe the outline and contents for the following eleven chapters of the book. The order of the book follows the life flow of deportees as they move from the Dominican Republic to the United States and then pass through prison and detention camps before being returned to their native country and, in some cases, making the return journey to their surrogate homeland. Although we have tried to keep this book sequential, based on the chronological narratives of the subjects, the reader may also choose to read chapters out of sequence because we have presented the data in such a way that each pathway stage can be read independently.

The next chapter takes us into the setting of the study. As explained earlier, the bulk of our interviews and research takes place in Santo Domingo, although numerous interviews were completed in prisons, in the city of Nagua, and in New York City. Thus, chapter 2 is devoted to a brief description of the history and conditions in the Dominican Republic followed by a summary and commentary on some of the main characteristics of our deportee sample.

Presenting the interview data for the first time, chapter 3 looks at the factors influencing the decision of subjects to leave their homeland, the contradictory feelings of loss and hope, and the mythical constructions of America imbedded in the daily lives of Dominicans placed in their historical context. This orientation toward the United States is discussed in its narrative and ritualized forms as both male and female subjects reveal the multiple scripts and practices that made their emigration seemingly inevitable. At the same time, we analyze the feelings of loss and ambivalence as well as the memories of family and community life left behind. We also describe the many means of “making it” to New York, Miami, or Boston, including nightmarish crossings to Puerto Rico, stowing away on ships from Santo Domingo, hiding in trucks along the Texas border to be later delivered like a package in the mail, and of coming as a child with skimpy clothing in the middle of winter.

In chapter 4 we focus on the lived experience of deportees, who are both first and 1.5-generation immigrants, as they struggle to adapt to a rapidly changing urban America during different epochs and time spans. We highlight the adequate and inadequate preparations made by subjects to make their transition successful and the realities of working-class, multiethnic barrio life in the First World. We pay particular attention to subjects’ accounts of neighborhood conditions, their experience of schooling, their plans for the future, the highs and lows of transnational family life, and their constant search for viable, meaningful work in a world of racially segmented labor.

In chapter 5 we consider the criminological “drift” of subjects into risk-prone social environments and the multiple sociocultural and economic influences that constitute their deviant trajectories. We show the great variety of orientations toward crime among the subjects, the importance of agency in their life course, and the webs of social control experienced by the Dominican community in various ethnic enclaves of the United States. Finally, we discuss the role of street subculture in the lives of subjects during their adolescence and their need to “fit in,” particularly among other lower class New Yorkers.

In chapter 6 the testimonies of deportees regarding their prison experiences are recounted, and this physically and psychologically arduous time is critically analyzed. Not a single interviewee made light of this period in their lives as they revealed multiple levels of privation, humiliation, and dehumanization endured in local, state, and federal prisons; in prison dormitories; in small, multiple-inmate jail cells; and in solitary confinement. We discuss how the subjects created strategies to withstand their years of incarceration, their decision to stay neutral or to join other prison gangs, their resolution to fight their case from the inside, their drive to organize other Dominicans, and their determination to pursue an education, however limited. We also highlight their feelings of social estrangement and culture shock that accompanied their confinement, the multiple levels of racism that are rampant in the prison system, and their constructive relationships with other inmates. In doing so, we also point out the ways that prison has changed during the recent era of mass imprisonment and the increasingly common roles played by immigration detention centers in the incarceration industry.

Chapter 7 begins the exiled part of the book. We discuss what it means and feels like to be deported from the subjects’ perspective. We answer questions about how deportees are processed, legally represented, and finally expelled through a court system that virtually predetermines the outcome. The deportees’ only chance for appeal is to prove that they will be tortured by agents of the receiving governments and that such practices are policy. For women, there is a second line of defense under the U.S. Violence Against Women Act of 1994, in which a deportee must prove that she faces certain violence and possibly death at the hands of a former husband, lover, etc. This too is almost impossible to prove in court; the numbers of imprisoned deportees winning their cases is minute. Using observational field notes from court hearings and personal testimonies of deportees and interviews with immigration lawyers and judges, we paint a vivid portrait of this critical turning point in the subjects’ lives and their range of responses, which vary from high levels of resistance to phlegmatic resignation.

When deportees arrive back in the Dominican Republic, what do they face? How are they received by their motherland? What levels of culture conflict do they experience? In chapter 8 we analyze these questions, focusing on the processes of stigmatization that are fueled by their pejorative or ambivalent identities as felons, deportees, Dominican/New Yorkers, failures, etc. We show how the Dominican media, politicians, and police leaders have contributed to the moral panic surrounding deportees as they are blamed for soaring crime rates and increasing interpersonal violence. Meanwhile, we analyze the psychological and cultural trauma experienced by many deportees as they come to terms with a society that is more parochial and homogeneous than the one they are used to. In many ways, this cultural encounter is the other, darker side of their transnationalism as they contend with their new master status.

Our analysis in chapter 9 focuses on the efforts, strategies, and models of personal and collective development of deportees. As we trace the economic strategies of our sample in their quest for daily survival, we provide a picture of the economic opportunity structures that await them and their attempts to build social capital and use whatever cultural capital they possess. With little tradition of meritocracy, massive levels of corruption and patronage, and highly unstable domestic formal and informal markets (including illicit drugs and the sex trade), we highlight the importance of social capital for deportees’ economic well-being. Finally, we discuss what happens to those deportees who cannot socially fit in or who cannot adapt to the economic climate and instead turn to drugs as a form of self-medication for depression or as a means to escape the endless rituals of degradation that daily life seems to bring.

Chapter 10 highlights the experiences and plight of those deportees who end up back in Dominican Republic prisons. Although the rate of deportee recidivism is low, there are significant numbers placed in preventive detention after indiscriminate sweeps through the neighborhood, during which deportees, many of whom are innocent, are singled out for crimes.

In chapter 11 we present the final segment of our data based on interviews with deportees who have returned illegally to New York City. Here we analyze the individual and collective strategies that subjects used to support themselves and their families and stay undetected. These are quintessential transnational subjects resisting their legal status, refusing to abide by the discriminatory rules of the colonizing nation that pulled them here and pushed them there.

Finally, chapter 12 is our summation of the entire work, bringing together the major findings and the range of contributions these make to the development of theory. We also make a number of policy suggestions that would ameliorate the conditions and plight of so many hapless victims of these inhumane laws.