CHAPTER ONE

A Breed in Any Other Place

When William Brown, the author of a “handy-book to the science and practice of British sheep farming,” described the geography of the principal breeds of sheep in the British Isles in 1870, he estimated that “no less than 63 per cent of the British Isles [was] still claimed by the native breeds.”1 The remainder was the territory, in his calculus, of the other dominant types of British sheep: Cheviots, the improved hillside breed that dominated Scotland and the north of England; Down sheep, originally adapted for the chalky hills and vales of southern England; and Leicesters, that most highly cultivated kind of British ovine, the creation of the esteemed Robert Bakewell (1725–1795), and the darling of late-eighteenth-century improvers. Unlike these well-defined and carefully honed breeds, the “natives” to which Brown referred were a motley crew, including the Blackfaced variety—a common designation that was itself a catchall category for various kinds of mountain sheep in England, Scotland, and Wales—and Irish sheep, a class about which “little,” Brown noted ruefully, “can be said in [their] favour.”2

Of course, there were many more breeds of sheep in the British Isles in the 1870s than these four, a fact of which Brown was well aware. Indeed, diversity of type was the hallmark of British animal husbandry. Nearly each region, each locality, boasted its own distinctive type of cattle or sheep, and it was these local kinds—many of which remained largely unaltered by the techniques of “improvement” that dominated British and Scottish agriculture from the late eighteenth century until well into the nineteenth—that Brown meant to encompass within the category of native. For Brown, this designation affirmed the effects of nature over those of human ingenuity or artifice when it came to shaping and determining type. Unlike Bakewell’s New Leicester breed (one “purely of man’s modelling,”3 as the author put it), Blackfaced mountain breeds and other native kinds had “had no handling except in careful selection among themselves.”4 Their form, according to Brown, had been determined entirely in response to their surrounding conditions, to the cumulative effects of competition, predation, scarcity, and sexual selection—what Charles Darwin, with the publication of The Origin of Species in 1859, had recently given wide public and scientific currency to as the processes of natural selection.

Map of the British Isles, “Exhibiting [the] Distribution of Prevailing Kinds of Sheep.” From William Brown, British Sheep Farming.

What it meant to call a type of livestock “native” to a particular place or environment varied considerably according to temporal, geographic, and political context. Indeed, it is the task of subsequent chapters to trace some of the situational variations in the idea of native breeds, as well as their political, cultural, and economic consequences, both within Great Britain and in parts of its former empire. But despite the wide array of meanings that could be—and were—attached to the term over the course of the nineteenth century (and beyond it), using it as Brown did to differentiate between highly cultivated improved types on the one hand and unimproved or local varieties on the other remained a consistent usage over time and across context. The predominance of this denotation, however, did not prevent other meanings from adhering to the word “native,” which was always multivalent when applied to livestock. Nor were the political implications and cultural, as well as economic, valuations that spun out from the idea of nativeness necessarily stable or narrowly construed: they could (and did) proliferate, varying according to time, place, and context. And yet, at a foundational level, calling a breed “native” worked to dissociate it, consistently and persistently, from notions of refinement, from cultivation, from purposive human design. This chapter explores the origins of the term as applied to breeds of sheep and cattle, arguing that this basic lexical stability can be traced to the “discovery” of native breeds during Great Britain’s fit of agricultural improvement in the late eighteenth century, and to the constantly shifting assumed roles for heredity, environment, and human selective pressure in understandings of a breed itself. Which of the latter of these—environment and climate, or anthropogenic selection—had the most significant impact over the former—the transmission of traits from parent to offspring—effectively shaped how agriculturalists at the turn of the century understood the notion of a breed. And while eighteenth- and nineteenth-century stockbreeders operated on the basis of a largely tacit body of knowledge, and in the absence of a convincing understanding of the principles or mechanisms of heredity (these emerged slowly, in piecemeal fashion, and amid much contention between the 1890s and 1920s) they were adept at recognizing and managing the effects of both inheritance and environment.

Every Soil Has Its Stock

Today it is understood that as the sum of flocks or herds, themselves aggregates of individuals, a breed is by definition subject to constant change.5 Animals are born, reproduce, and die. In the process, some—but not all—traits or characteristics are transmitted across generations, and therefore the appearance, instincts, and even the behavior of particular individuals are liable to diverge from that of their fellows or forebears. How a given population looks or behaves—what it eats or how it reproduces, where it migrates or the range it is able to inhabit—are thus all subject to change over the course of generations. This means that a breed is an inherently unstable thing, the word itself denoting a sense of transmission absent in synonymous terms such as kind, type, variety, strain, or race. It came into wide currency “among husbandmen” only in the early nineteenth century as a way to distinguish between “varieties [of stock], possessed of peculiar characters” precisely because its relation to the verb to breed suggested the means by which “it is supposed their respective properties are in great measure communicable to their descendants.”6

Never entirely containable by the methods of selective breeders, any breed’s genome contains enough variation that individual phenotypes will differ considerably. Even in a “closed” breed—inbred for many generations to produce homogeneous genotypes in its composite individuals, and therefore a relatively stable phenotype—genetic drift sufficient to modify the overall characteristics and appearance of the breed is the norm. Indeed, the purebreeding techniques of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in which consanguineous individuals (including, often, parents and their offspring) were bred to each other, worked to forestall as much as possible this inevitability by concentrating certain qualities, in contemporary parlance, or honing the genotype, in modern terms. The peril of purebreeding was that such pairings could concentrate undesirable traits as well as desirable ones, but it was nevertheless the preferred approach to stockbreeding, and a necessary one. As John Sebright explained in 1809 in an influential pamphlet on breeding, “Breeding in-and-in, will, of course, have the same effect in strengthening the good, as the bad properties, and may be beneficial, if not carried too far, particularly in fixing any variety which may be thought valuable.”7

This tendency to variability—one common to all forms of life—though, could also be an advantage to livestock breeders. It was, in fact, the material starting point for selective breeding. “Individual variety of size and shape prevails in all breeds,” John Lawrence—an expert on the “breeding, management, [and] improvement of domestic livestock”—wrote in 1805, “to the infinite use and convenience of man.”8 Or, as Charles Darwin put it in the introduction to the first volume of Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868), “If organic beings had not possessed an inherent tendency to vary, man could have done nothing.”9 This innate and inevitable tendency was crucial. It produced a gap between heritability and physical appearance—between genotype and phenotype—that offered breeders, as it were, the space to experiment with selection. “Although man does not cause variability, and cannot even prevent it,” Darwin wrote, “he can select, preserve, and accumulate the variations given to him by the hand of nature almost in any way which he chooses,” and in this way, the careful breeder of livestock can thereby “certainly produce a great result,” whether this was the production of long or fine wool, rich or copious milk, fine hides or fatty meat, or some combination thereof.10

Beginning in the late eighteenth century, this was increasingly the territory of enthusiastic agriculturalists working under the sway of an ethos of “improvement.” As a guiding philosophy, improvement was applied to many branches of rural economy—to agricultural technology and farming implements, crop yields, the study of soil content and quality, to large-scale environmental engineering projects of draining and irrigation, and even to the climates of northern locales in an effort to ameliorate them11—with the overall goal of rationalizing, and thereby increasing the productivity of, the agricultural sector of Great Britain. It resulted in several major developments, not least among them the transition from common grazing to enclosed pasture and cropland, a sweeping change to the landscape of the British Isles, with devastating social consequences, especially in Scotland.12 More prosaically, but perhaps no less revolutionary in the long run, agricultural improvement also gave Britain the rutabaga, or Swede: originally a humble Swedish vegetable, it dramatically transformed livestock feeding and fattening.13 And it led to the widespread adoption of the four-field system of crop rotation, in which “the cultivation of clover and rye-grass, joined to … turnip husbandry” and to the pasturing of livestock, resulted in “such luxuriant crops of grain … as could not be produced, by any other means.”14 Improvers, many of whom hailed from the landed aristocracy, promoted such efficiency at all scales, from the smallest holding to the greatest estate (although they continually bemoaned the common farmer’s resistance to such activity), efforts they undertook in the name of enhancing the prestige along with the material well-being of Great Britain.

Agricultural improvers turned their eye toward the nation’s hordes of sheep and cattle, too. Under the gaze of improvers like John Sinclair, John Southey Somerville, Arthur Young, and others, the regionally, even locally, distinguishable breeds that predominated in England, Scotland, and Wales in the late eighteenth century increasingly came into focus. In fact, the modern notion of a “breed” as a replicable type itself gained currency around the same time in recognition of two concurrent foci in the shaping of livestock—the ability of a skillful breeder to impress human desiderata (size, color, form) on a group of animals, and increasing awareness of the variety and distinctiveness of type throughout the British Isles.15 Acknowledgment of both arose in consequence of the spirit of improvement that marked agricultural pursuits at this time, the former from the practical application of this philosophy to livestock production, and the latter from the movement’s attendant desire to promote useful agricultural knowledge. Enthusiasm for useful knowledge, which of course extended well beyond the agricultural sector, and only increased over the course of the nineteenth century, spurred the growth of a genre of agricultural reportage describing rural affairs throughout England, Wales, Scotland, and eventually Ireland, designed to encourage enlightened practice among the nation’s landowning class.16

In addition to accounts of geological and climatological conditions, farming economy, statistical values relating to arable and pastoral production, and detailed descriptions of the gardens, houses, farm buildings, and cottages of great estates, the “general views,” commissioned by Great Britain’s Board of Agriculture, contained details of the particulars of a region’s livestock. In aggregate, these accounts of rural economy and animal husbandry offer a picture of a system of livestock breeding at the commencement of the nineteenth century remarkable for its diversity. Each region contained its own, usually eponymous, type of cattle and/or sheep. Breeds were called after their particular localities not merely from convenience or because that was where they could be found, but because it was assumed that the character of a place infused the character of a breed. The cattle of Cambridgeshire, for example, were “mostly the horned breed of the county, and are called by its name,” according to William Gooch,17 while in the southwest of England, Devonshire cattle predominated, “and this breed, more or less pure, prevails throughout Cornwall,” according to George B. Worgan, author of the General View of the Agriculture of the County of Cornwall.18 Gradations in type were common, particularly so if the area in question was large, like the Southwest of England. Writing in 1807, Worgan carefully distinguished the fine differentiations within the Devonshire type, North Devons (the preferred breed of “the more enlightened and spirited breeders”) being fine and somewhat delicate, while South Devons, “more of a brown, than of a blood-red colour” were “considered stronger and more hardy.”19 Breed, or type, was understood to be intimately connected to the nature of a place. In a region of variable geology and climate like Cornwall, where a “great diversity of soil prevails … as well as difference of situation in regard to shelter and exposure, it is not to be wondered at,” wrote Worgan, “that the cattle which are bred and fed thereon, should also vary much in size and other properties, occasioned by local circumstances.”20 Indeed, that “every soil has its own stock” was the presiding understanding of the differentiation of breeds within Britain at the turn of the nineteenth century.21

The emergence of modern genetics and developments in the field of animal science in the twentieth century have given subsequent generations of theorists and practitioners the conceptual tools with which to develop precise understandings of inheritance, and the role of environment in selection, both artificial and natural. It is now generally conceded that the influences of heredity predominate over the influences of a given individual’s environment, and by extension, over those of a population.22 But because the operation of heritability remained a puzzle throughout most of the nineteenth century, no such consensus then reigned. Consequently, a breed’s relation to the influence of environmental surroundings—climate, herbage, soil type, seasonal variation, and so forth—remained open to debate, and the relative contributions of climate and environment, on the one hand, and heredity and selection on the other, were difficult to tease apart.

It was clear to all with knowledge of the subject that inheritance was central to the breeding of superior animals. But it was clear, too, that external conditions played their own role in shaping type. The sheer variety of livestock populating the British Isles lent weight to the supposition that the character of a place infused the character of a breed. Great diversity reigned across British pastures, from the shaggy Kyloe beasts that grazed the inhospitable moors of the Scottish Highlands or the old Longhorn type of Lincolnshire in the northeast of England, to the robust and beefy Hereford, or the highly refined Shorthorn type. Nor was such variety limited to the bovine species. The simplified four-part typology of sheep that William Brown mapped onto the British Isles in 1870 masked a wider array of ovine types including the rare and peculiar (the Herdwick sheep of the Lake District, for instance, which were celebrated for their unusual homing instincts; or the singular breed of North Ronaldsay in Scotland, which evolved to forage for seaweed at low tide), as well as the relatively widespread and more familiar. The fine-wooled Ryeland sheep of Herefordshire; the large and rawboned breed of Lincolnshire; the multihorned and multicolored Shetland breed; the fat Wiltshires, Shropshires, Dorsetshires, and Southdowns; the long-legged and long-wooled Romney Marsh sheep—each distinctive place could claim its own distinctive breeds.

Sheep breeds characteristic of the “Higher Welsh Mountains,” showing various degrees of “improvement.” From David Low, Breeds of the Domestic Animals of the British Islands, Volume 2, Plate 2. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

Indeed, so evident did this connection between environment and type seem that no one “who has ever had an opportunity of considering the subject,” opined John Sinclair, a leading agriculturalist of the late eighteenth century, would “ever entertain the idea, that only one breed of sheep, ought to be propagated in these kingdoms.”23 This sentiment held particularly true for sheep, a species that, at least in the British Isles, seemed subject to an especially high degree of variability. Though “all animals are subject to variety as determined mainly by breed and climate,” Brown claimed, “no kind of animal varies so much as the Ovis in adapting itself to circumstances, or becoming acclimatised.”24 As Sinclair put it, the “hardy and plastic nature of the animal itself” was a match for the “variety of ground on which it may be safely pastured,” lending evidence, in his view, “that nature intended, that there should be a considerable diversity of breeds, even in the same individual country.”25 According to Brown, recognition of this provided “the great starting-point in sheep-culture.”26 And by the time at which he was active, thanks in no small part to the explorative efforts of earlier generations of improvers, the idea that the different “habitats” boasted “prevalent breeds of sheep adapted to them” was common knowledge.27 “Most people,” he wrote, “have an indefinite general knowledge on this question; they have often heard it spoken of in an incidental way, and they know … that a Down [sheep] will not thrive on the Grampians,” even if the “particular reason” for this eluded comprehension.28 Although the precise “influence of climature, on the constitution, or changeable part of the nature of animals [was] a matter of difficulty to be demonstrated,” as an authority on rural economy writing in the late eighteenth century realized, its effects were manifest. “No man has yet been able to breed Arabian horses, in England,” this author continued, nor “English horses, in France or Germany; nor Yorkshire horses in any other District of England.”29

But just as the variety of native types of sheep and cattle could be marshaled as evidence for the effect of climate and environment upon breeds of animals, so too—paradoxically—could it be claimed by those who argued in support of the primacy of inheritance over external conditions. This was particularly apparent when it came to the various qualities of wool grown in the British Isles. “Although we should be disposed to attribute ever so much to the influence of the climate of G. Britain,” the author of a 1774 essay on “the improvement of the Highlands” remarked, “yet the difference between the heat of the climate of different places in this island that afford wool of very different qualities, is but very inconsiderable.”30 The diversity of breeds in Great Britain was impressive; its climatic range less so. Not only do conditions and temperatures vary relatively little from place to place, seasonal fluctuations are also limited. With the exception of pockets of extremity—the west coast of Scotland, for instance, or the Peak District in Yorkshire—the British Isles are consistently humid and temperate nearly everywhere. Given this stability, climatic variance alone could not account for the wide variety found among British sheep (and cattle). “Many parts of England enjoy a climate nearly similar to that of Herefordshire and Gloucester,” this author noted, “yet wool of an equal quality is not to be met with there.”31 It was not climatic differences or the nature of the pasturage but the “very great diversity that we find in the nature of sheep,” he claimed, that accounted for the varieties of wool grown in the British Isles.32 When it came to understanding the relationship between types of livestock and the places in which they could be found, the evidence, it is clear, remained open to interpretation.

The Eye of the Breeder

If the evidence itself was open to debate, the grounds upon which it was produced were less so. Overwhelmingly throughout the nineteenth century, claims to authority and expertise on what made a breed a breed were made upon the basis of experience combined with careful observation. Before it was codified as genetics or sanctified as a scientific field, knowledge of how characteristics were transmitted from generation to generation operated tacitly.33 The stuff of livestock breeding was an applied knowledge, a kind of barnyard science, and therefore difficult to transmit in the absence of practical experience. There were limits to what could be conveyed by pen and ink: knowledge gained “by an accumulation of circumstances—ordinarily called experience”—was paramount.34 William Brown believed that “any amount of reading without the long daily experience of the grazier [was] of little service to the young husbandman.”35 Others concurred. In 1875, a columnist for the Livestock Journal and Fancier’s Gazette, a weekly publication devoted to the breeding and rearing of pedigreed livestock, poultry, and pets, expressed frustration over the incapacity of “fanciers and breeders … for appropriating knowledge” of practical breeding from the pages of the journal, given that such knowledge “cannot be taught in words.”36 Rather than prompting a crisis of professional identity (for what good was a journal devoted to livestock breeding if such knowledge was intransmissible by ink and paper?), this lamentable observation spurred the writer to ruminate on the nature of the “art” of breeding: not an “instinctive” one, it was “simply the result of experience … constantly accumulated and gathered up to be applied throughout succeeding seasons,” and the “thinking breeder” was therefore “ever keeping his own eyes open to apply what he has learnt from others to his own experience.”37 By these means—patience, observation, experience—was “mastery of [this] … particular branch” of knowledge assumed in the absence of what one historian recently called “a functional explanation of biological inheritance.”38

Experience on the ground, so to speak, and keen observation, then, were deemed critical to breeding of any kind, improved or otherwise. In the debates that marked livestock breeding throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these two components remained the benchmark for knowledge and the basis of authority. John Little, author of Practical Observations on the Improvement and Management of Mountain Sheep, and Sheep Farms (1815), found the courage to publish his views on “the intricacy of this very interesting subject” based on his thirty years’ experience as a shepherd and sheep farmer.39 Most other authors on the subject of “mountain sheep-farming” “were not practical men,” he noted in his preface, alluding in all probability to the fact that the backers of agricultural “improvement” largely hailed from among the wealthy, landed, elite. They rarely got their boots, much less their hands, dirty, preferring instead to delegate the practical work of selective breeding, rearing, and general farm management to a team of practical experts (like Little), overseen by a paid steward.

Consequently, Little claimed, the information their works contained, and the rules they had “laid down … for the management of every kind of mountain stock, and of mountain farms however situated with respect to soil and climate,” were not based on firsthand knowledge.40 By contrast, Little’s own volume was founded, he claimed, entirely upon “the experience I have had in different parts of Scotland and in Wales.”41 This gave him the authority to publish eight chapters on topics ranging from the relative merits and description of the Cheviot breed, to the life of a shepherd, to “observations on the improvement of the country by means of railways.”42 And if, he eventually concluded, he had “fallen into any [errors]” along the way, he was careful to note that it was not because he had “indulg[ed] any favourite theory, but entirely from the inaccuracy of the observations I have made in the course of my practice as a shepherd.”43

The emphasis that experts placed on the weight of experience helped ensure that the relationship between the formal sciences and the practice of breeding in the nineteenth century was a distant one.44 Those familiar with both the workings of scientific inquiry and the breeding of livestock agreed that even proximal sciences like physiology and anatomy offered little recourse to practitioners. For instance, John Hunt, a physician and a great livestock enthusiast (though not a practical breeder) who claimed Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802)—the well-known botanist and eventual, albeit posthumous, grandfather to Charles—as his “learned friend,” wrote in 1812 that “the breeding and feeding of domestic animals [was] not to be explained” by the “parade of philosophy,” but rather by “a knowledge of nature.”45

But it was not merely that formal scientific theory appeared to have little bearing on the practice of breeding. Breeders, too, tended to overlook developments in fields like natural history that might have furthered their own aims. This remained the case for the most part even after what we now consider to be some of the most significant developments in what became the disciplines of biology and genetics. The wide acceptance of Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, for example, and his attendant theories of artificial selection, had surprisingly little impact (at least from the modern perspective) on the work of stockbreeders in the latter decades of the nineteenth century. In 1902, for instance, the New Zealand Farmer, the dominion’s premier agricultural publication, quoted an unnamed writer for an unspecified “English agricultural journal” who lamented the fact that most sheep breeders remained ignorant of the principles of artificial selection that Darwin had laid out in Variation some thirty-four years earlier. “So many years have passed since Darwin has published his two-volumed ‘Animals and Plants under Domestication,’ ” he wrote, “that it should have been impossible for any ewe in any well-to-do farmer’s flock to produce less than twins except as a rare and unwelcome throw-back to earlier habit.” That evolution tended toward multiple births he took for granted, and in failing “to follow Nature’s plan and eliminate the less fertile generation after generation,” breeders had hampered the progress of ovine evolution and stunted the wealth and prosperity of British agriculture. “If the matter had been scientifically attended to,” he claimed, “our sheep should now be passing into the triplet-bearing stage of evolution, fully provided with stamina and milk-producing powers to keep pace with such increased fertility.”46 While ewes bearing litters of lambs may seem a far-fetched evolutionary eventuality, even with the optimism and unquestioning faith in the human capability to mold nature that this writer displayed, the gulf between the science of inheritance and the practice of livestock breeding was a real one. Already apparent in the early nineteenth century, the distance between the two widened and persisted until well into the twentieth century, as Margaret Derry has shown in her recent survey of the science and practice of breeding since 1700.47

Even so, this robust body of knowledge founded on practical experience meant that collectively breeders understood the “communication of qualities” across generations very well.48 If the innate variability of living creatures was the material starting point for selective breeding, the “general rule [that] the young resemble their parents in form and properties” was the conceptual one.49 Simply put, “in the common phrase,” that “like produces like” was the well-known maxim of livestock breeding.50 “Blood” served as a metaphor for the means and substance of heritability, though contemporaries were aware that it was “nothing more than an abstract term,” as one theorist put it, “expressive of certain external visible forms which, from experience, we infer to be inseparably connected with those excellencies which we most covet.”51 That this link between external excellencies and heritability remained largely unsubstantiated was less troubling to breeders and practitioners than might be assumed. For most, it was enough that their tactics worked: the proof, so to speak, was in the progeny, which were demonstrably fatter or woolier, or better milkers, after several generations of selective breeding.52

Because heritability was necessarily an embodied phenomenon, the ability to discern particular traits, qualities, or characteristics of certain animals—such as early maturity, fattening ability, a certain bone structure, a generous fleece—was paramount. “Intelligent breeders are now aware,” wrote Andrew Coventry, an early authority on breeds and breeding, “that the different kinds of our domestic animals have ‘points,’ ie. forms and proportions of parts, and likewise certain other properties, which are differently estimable.”53 To discern among them, and to weigh their relative values, required “patient observation and assiduous research” on the part of the breeder who “should try,” he counseled, “by actual measurement to improve his eye, on which at last most persons come to depend, and with sufficient propriety, as it becomes wonderfully correct.”54 Once so trained, using this expert judgment required the dexterity of a balancing act. As Sebright explained, “We must observe the smallest tendency to imperfection in our stock so as to be able to counteract it, before it becomes a defect; as a rope-dancer, to preserve his equilibrium, must correct the balance, before it is gone too far, and then not by such a motion, as will incline it too much to the opposite side.”55 For breeders, this meant a perpetual process of keen appraisal and careful correction. Quality remained important, of course: if you wished to possess a superior strain of cattle or sheep, “you could but breed from the best,” Sebright advised.56 But the art of breeding was not so much about “always … putting the best male to the best female.” Rather it required the ability to both meld the best qualities of a pair and cancel out their worst. “Were I to define what is called the art of breeding,” Sebright wrote, “I should say, that it consisted in the selection of males and females, intended to breed together, in reference to each other’s merits and defects.”57 On this careful scrutiny hinged the whole endeavor: “The breeder’s success will depend entirely,” he warned, “upon the degree in which he may happen to possess this particular talent.”58

Transposition and Transmutation

In attempting this delicate balancing act, breeders and stock-raisers also needed to distinguish between the effects of external factors—climate, feed, conditions of management—and the inherent characteristics of their animals. Increasingly, the undertakings of those bent on the improvement of British husbandry complicated this task. Picking up a breed from one place and moving it to another, and the evident changes such actions wrought on individuals and their progeny, called into question the nature of the relationship between type and place. It also contributed to the general confusion over cause and effect in the mechanisms of heredity. As Andrew Coventry, author of the well-reputed Remarks on Live Stock and Relative Subjects (1806), remarked, some breeders, “having discovered that certain properties were less steady when circumstances were changed, have been disposed to conclude, that all are more or less mutable … according to the influence of the changing powers.” But in “a situation where circumstances were less varied, and where of course alterations on the form and character of animals were less frequent and striking,” breeders “collecting their observations” there were “led to draw an opposite conclusion,” the stability of the conditions of their observations suggesting that “the appropriate qualities were innate and immutable.”59 Heredity and environment were impossibly entangled.

Transpositions at the colonial scale threw this problem into sharp relief. In the early nineteenth century the paradigmatic example of the confusion born of relocation was that of European sheep transposed to the Caribbean, where a few generations seemed to wholly alter the character of these translocated ovines. “The heat has such a strange effect upon the sheep, in the West-Indies,” observed one commentator, “that hair like that of a goat, grows upon them, instead of wool.”60 This appeared to be true no matter how “fine and close their fleece might have been in their native country.”61 It was, moreover, common knowledge—“a fact that all our seafaring people who frequent warm climates are well acquainted with,” according to one gentleman who published under the name “Agricola.” “When they export any live sheep from Europe to supply themselves with fresh provisions,” he wrote in the Scots Magazine in 1774, “they always find, that … what springs upon them in warm climates is only a thin straggling coat of a particular kind of hair, hardly at all resembling wool.”62

While general interest periodicals and agricultural journals alike were rife with such assertions, other interested parties were quick to counter that the seemingly strange action of the tropical sun was rather the old action of like producing like at work. The “notion of sheep losing their wool, and becoming hairy, after remaining a few seasons in the climate of Jamaica” was a “groundless” one, as John Lawrence asserted in no uncertain terms. The perceptible changes that overtook European sheep “doubtless” came from “intercopulation with an hairy breed” already established there, and “in course, suffered to intermix with our woolly breed.”63 In fact, such ovine miscegenation was a common occurrence. Nor was it limited to colonial conditions, given how “impossible” it was, according to another expert on Scottish sheep farming, “by any ordinary care [to prevent] any strange sheep com[ing] into a different district … from intermixing with the native sheep at the rutting-season.”64 And as the progeny of that first illicit coupling “[ran] the same risk of being farther debased than their parents were, it must of consequence follow, that, after a few generations, they will have so far lost their distinctive marks as scarce to be distinguishable from the sheep with which they are now associated.”65 The outcome, he explained, was “invariably a mongrel breed,”66 in which local and introduced (read: improved) breeds alike were “debased” by careless husbandry, whether in Scotland or the colonies. Whatever the causation, the implication of accounts that described transplanted European sheep introduced to colonial places “assum[ing] a covering fitted to the climate, [and] becoming hairy and rough,” was that they thereby degenerated from their previous heights of cultivation.67

Discourse of this sort bore not only the character of four-footed creatures. It played upon a more generalized anxiety about human transposition that attended the colonial endeavor, and this gave the issue a more lasting purchase than it might otherwise have had. Beginning in the early modern period, as Europeans settled in foreign places that were home to unfamiliar plants, animals, and people, they wondered at, and worried over, the potential impact such radical dislocation would have on their own bodies. The idea that human beings were sensitive—for better or worse—to the effects of their surroundings, and that some kinds of people were better suited for particular climates than others, was a long-standing commonplace in European thought, and it shaped the thinking of all sorts, from physicians to philosophers.68 Health and well-being were particularly vulnerable to the action of environment in the Galenic framework that defined medicine and dietetics from antiquity until the nineteenth century. Ill health signaled an imbalance between body and environment, while well-being could be restored by correcting (with the aid and expertise of a physician) this imbalance. This, combined with the long-standing idea that the nature of a people (e.g., cold, hardworking) was suited to, and in some degree defined by, their geography (e.g., Northern Europe), meant that the idea of settling distant, unknown lands could be disquieting for European colonists.

Although the valences ascribed to human physiological acclimatization were not fixed—during the early period of settlement in North America, for instance, English settlers took some solace in the idea that their bodies would eventually adapt to their new surroundings, as Joyce Chaplin has shown—as the British Empire of settlement expanded into more and more distant territory (biologically as well as geographically) over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the vulnerability of human bodies to the influences of their environment became increasingly disquieting.69 Such anxiety was an undercurrent that ran through discourse and debate like the one over the effects of tropical environments on European sheep, and it rose to the surface with refutations of the action of the tropics on animal bodies. The mongrelization of translocated sheep was a matter of interest and a source of worry precisely because it potentially prefigured the racial degeneration of human colonists. Breeds of livestock offered a rough analogy to races of people, and both were vulnerable to the perils of acclimatization.70 These included the immediate risks of bodily adjustment (called “seasoning” for both animals and people) as well as the potential for typological change or adaptation on a more permanent basis. The stakes of the debate could not be higher. So when John Lawrence refuted the effects of Jamaica’s sun on the wool of British sheep—“That sheep of any species, if strictly preserved from foreign intercopulation, would retain their natural characteristic wool for ever, upon the island of Jamaica … there is not the slightest reason to doubt,” he chastised his credulous readers, “since such phenomenon accords with the constant tenor of our experience”71—in the next breath, he spoke to the perils and promise of the human colonial endeavor. “The residence of a long-haired European colony … in the heart of Afric [sic],” he wrote, in a tone typical of the nineteenth-century Briton’s confidence in his innate superiority over other races, “no intergeneration with the natives taking place, would not deprive the former of the original external European character stamped upon them by nature; would not be able to transform them into woolly-headed shangalla.”72

The Extremes of the Country

What held true for people also held true for sheep, and vice versa, whether in Jamaica or Scotland, Cambridgeshire or Cornwall. And while the circulation and relocation of breeds within the British Isles never produced effects as dramatic as those of Anglo-Caribbean colonial transposition, they did significantly alter the landscape of British agriculture. Though the effects of climate and environment relative to those of heredity and selection in shaping the characteristics of a breed remained open to debate, the great enthusiasm for transposing kinds together with the rigorous interventions in heredity that marked agricultural improvement made it increasingly difficult to maintain faith in any simple one-to-one relationship between environment and type. By the early years of the nineteenth century, regional distinction had, in many cases, become confused by the efforts of improvement-minded farmers and landowners to augment their profits on the backs of exogenous breeds. In Gloucestershire, for instance, the predominant breed was “that of the Cotswolds, a type large and coarse in the wool,” but Leicesters, Southdowns, Wiltshires, Somersetshires, and the Ryeland breed could all find their champions there.73 In Cornwall, where “the climate and soil … [are] particularly favourable to the production of the finest fleeces,” but where wool-growing suffered from want of a local wool fair to stimulate the ingenuity of breeders, the local “true Cornish breed of sheep” had already by the close of the eighteenth century been mostly replaced by other breeds “introduced at different periods … of the Exmoor, Dartmoor, North and South Devon, Dorset, Gloucester, and Leicester sorts.”74

No breed was more widely diffused throughout the British Isles, or more perfectly improved, according to contemporaries, than the New Leicester Longwool, the celebrated creation of Robert Bakewell. Noted for both his skill in controlling the variability of his flocks and his business acumen when it came to maintaining control over the reproductive potential of his improved breed, Bakewell “fixed” the characteristics of the New Leicester Longwool by rigorously selecting individuals displaying his desired type (animals not conforming to his ideal were sent to slaughter), and subsequently inbreeding close relations in order, in modern terms, to hone the genotype and thereby stabilize the phenotype of his breed. Improvement in the case of the Dishley breed, as it was sometimes called after the farm at which Bakewell undertook its improvement, meant a round carcass, heavy hindquarters, light offal and bones, and animals that were quick to reach maturity.75 The Dishley was hailed by its contemporaries as the pinnacle of perfection and the ultimate in man’s ability to bend the natural to his will: “To such extreme perfection has the frame of this animal been carried,” enthused Lord Somerville, a leading improver of the age, “that one is lost in admiration at the skill and good fortune of those who worked out such an alteration. It should seem, as if they had chalked out, on a wall, the form, perfect in itself, and then had given it existence.”76 So thoroughly had the New Leicester Longwool been remade in the hands of Bakewell and other improvers that it had become an entirely synthetic kind.

The New Leicester or Dishley breed of sheep. From David Low, Breeds of the Domestic Animals of the British Islands, Volume 2, Plate 19. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

The Dishley thus stood in sharp contradistinction to those breeds where the effects of nature seemed to prevail more so than “the hand of man.”77 Indeed, the idea of a “native” breed was born out of, and depended upon, this contrast for its own existence. While improved breeds like the New Leicester Longwool seemed wholly artificial—its “remarkable [reproductive] precocity” was a particular mark of its “being so much artificial,” as William Brown put it78—unimproved “native” breeds appeared stubbornly uncultivated, and in many cases even uncultivatable. So much did “certain varieties … seem to have been shaped chiefly by the nature of their environments,” opined Brown’s theoretical heirs A. H. Archer and James Sinclair at the close of the nineteenth century, that the “physical characteristics of the country” probably “contributed in perhaps a greater degree than methodological selection on the part of breeders to the production of many of our existing races.”79 As Brown himself described it, the Scottish Blackfaced breed—one of those varieties which he classified as “native” and a type hailed for its superior wool and hardy constitution—was the Leicester’s polar opposite in this regard. “There is as much difference betwixt these sheep,” wrote William Brown, “as there is between hothouse and hardy plants.”80 If the Dishley breed was the ultimate in man’s ability to form and control nature, the other was almost wholly the product of nature itself, subject only, as Brown believed, to “selection among themselves.”81 Together, they represented “the extremes of this country.”82 “Native” breeds emerged as the dark side of improvement’s moon.

Once the New Leicester Longwool was fixed as an improved breed able to produce generation after generation in conformity with its type, the breed’s influence spread rapidly throughout Great Britain. Both Bakewell’s methods and his breed were adopted by “enlightened” breeders throughout the United Kingdom. Some followed his lead by inbreeding their own stock in order to “fix” desired characteristics, but most crossed their preferred breed with an already improved type, usually the Dishley.83 The desirability of the New Leicester was such that Bakewell was able to exert a monopolistic influence on the market for improved sheep-breeding. Bakewell charged dearly for the use of his stud stock and maintained tight control over their reproductive capacities. At the height of his career, other breeders could pay the exorbitant price of £300–£400 to use his rams on their own ewes for a single season, provided they agreed to castrate all male offspring, but ewes of his improved type were never available for widespread use, which meant that Bakewell alone could lay claim to completely “pure” New Leicester sheep.84 Other eminent breeders who agreed to let their own stock upon similar terms (although not at such a high profit) were, for the hefty sum of £100, granted membership in the select brotherhood of the Dishley Society, and given unlimited access to Bakewell’s studs. Together, these means directed the use of the Dishley’s reproductive potential, and capitalized upon its “genetic template,” a business development easily as revolutionary in the realm of livestock breeding as the reformulated breed itself.85

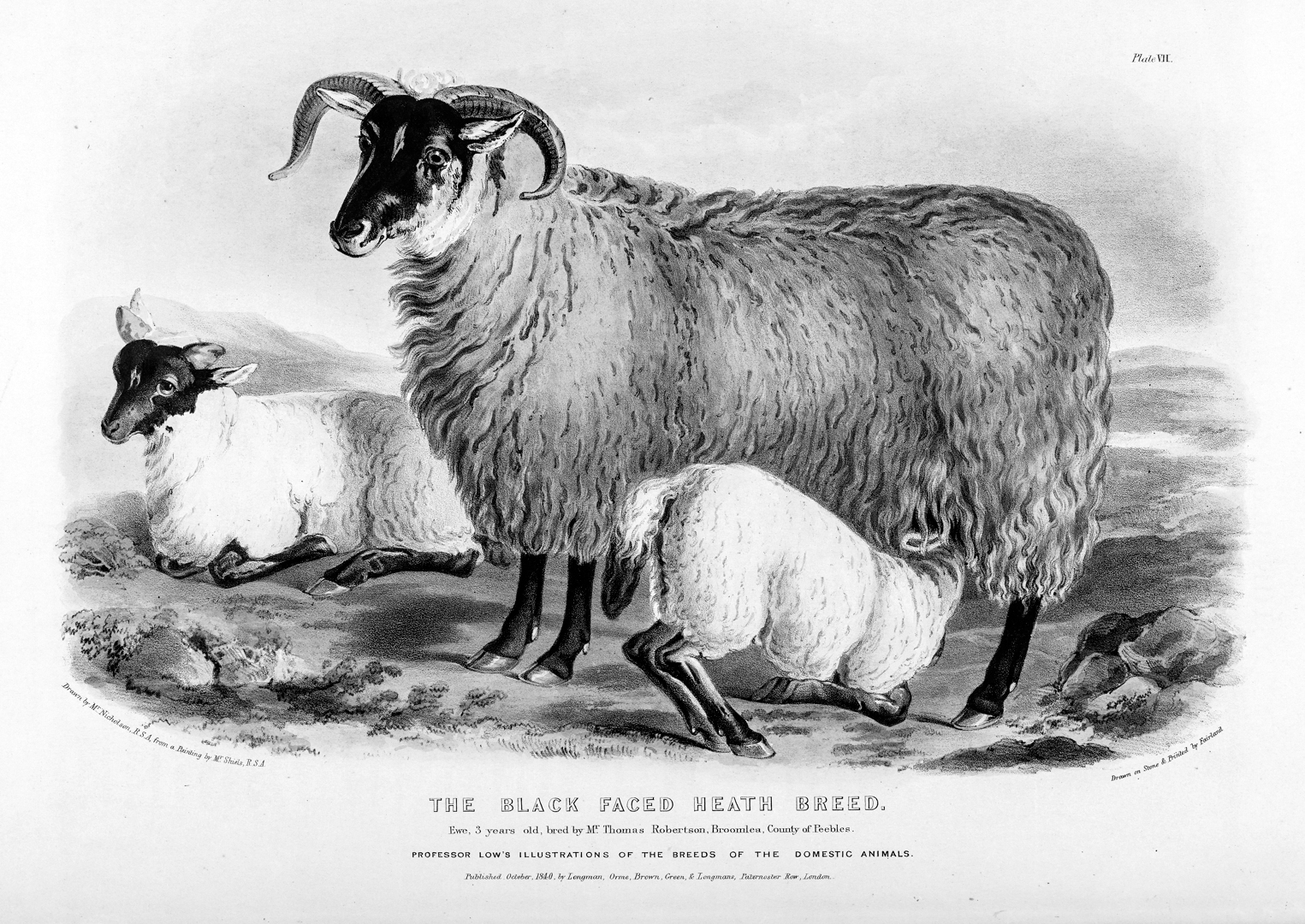

Black-faced heath sheep. From David Low, Breeds of the Domestic Animals of the British Islands, Volume 2, Plate 7. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

Notwithstanding the outrageous costs of access to the New Leicester Longwool, its influence spread far and wide. By the first decades of the nineteenth century, few breeds remained in existence without some mixture of Leicester blood. At first, even in places where doubts “as to the merits” of the new breed prevailed, such as Sherborne in Gloucestershire, “even the advocates for the old native breed allow a cross from the latter, if not carried too deep, to be an improvement.”86 As the ethos of improvement turned in the case of livestock production to efforts to increase the yields of meat, milk, and wool, the “native” breeds of the various regions of the British Isles began to fall by the wayside. The old Cornish breed was one of the first to succumb to the influx of improved competitors. Already by 1807, a spate of such introductions to Cornwall ensured that the “pure Cornish sheep [was] now a rare animal, nor,” according to Worgan, “from its properties”—including “grey faces and legs, coarse short thick necks … narrow backs, flattish sides, a fleece of coarse wool” and “mutton seldom fat”—“need the total extinction be lamented.”87

And the influence on British stock was profound: scarcely a breed, much less a region, remained untouched by the improved Leicester. Not only the Cornish type, but “the pure breed[s]” of Gloucestershire, Norfolk, and various other localities became increasingly rare.88 Accordingly, at just the moment local breeds were gaining recognition and wider currency, their particular traits adapted for local conditions were beginning to be stamped out in favor of more generalized adaptations to a growing national market. Crossbreeding, it was well recognized, served to sever the ties between type and locality. As Brown wrote, it was “quite possible to bring even the mountain breed”—that most different in form and habit from the Dishley—“to prefer the Leicester lands, by simple though attentive crossing and recrossing.”89 Through crossbreeding with the improved Leicester, a type formulated for the fast and effective production of meat, British breeds became increasingly homogenized as market standardization superseded the regional and even local specialization that had previously characterized British livestock.90

Making Meat

A national appetite for British (or sometimes for English) meat emerged in the nineteenth century concurrently with, and partly dependent upon, this standardization of local breeds. Population growth, supported by increased industrialization, higher agricultural yields, and better nutrition, supported, among other things, the emergence of a middle class in Britain beginning in the mid-eighteenth century.91 A more comfortable income for more of the population in turn encouraged the growth of markets for staples and luxuries alike. Such appetites were discursively underpinned and furthered by the expansion and increasing specialization of the periodical press, which contributed to the formation of class-based and national tastes, both for cultural artifacts and pursuits and, increasingly, for meat. Together, these developments placed a premium on the production of British meat: increased spending power meant that mutton, beef, and lamb composed a greater proportion of more people’s diets, while specialist and general readership presses increasingly emphasized this as a defining mark of Britishness.

Meat became central not only to the British diet but to a sense of nationhood and identity, a connection that was forged in no small part through the patriotic rhetoric of improvement.92 The high status of livestock breeding in Britain was due not only to its profitability but to “John Bull’s respect for his own table.”93 Those involved in this endeavor drew a direct connection between the efforts of stock breeders to perfect the meat-making capabilities of their stock and the well-being of Great Britain. A healthy population was the mark of a healthy nation, and for Britain, whose population was burgeoning at this time, a supply of adequate and wholesome food was a primary concern.94 John Hunt held strong views about the ways in which a love of country could be expressed through agricultural undertakings. Although he was willing to concede that it was “more the business of the politician” than of a physiologist such as himself to determine “the degree of population which would be most consistent with the happiness of Great Britain,” it was manifest that “the increase of population and the improvements in agriculture must of necessity be connected with each other.” Thus he held that it was “the first duty of the agriculturist to make the most produce of the soil.”95 Indeed, “if patriotism [was] not an empty name,” Hunt cried from the pages of a self-published pamphlet, “so long as the power, the dignity, and the prosperity of a country can be supposed to depend upon the health and happiness of a people, that the sacred character of the patriot will appear in no less splendour in the agriculturalist, who supplies the poor with wholesome food, than in the soldier who defends his country with the sword.”96

Though rarely stated in such effusive terms, similar views on the importance of agricultural production in general, and breed improvement in particular, were widely held. John Sinclair declared this “so great an operation” that “the public alone [was] equal” to its task.97 Improvement served not merely to line the pockets of the likes of Robert Bakewell. Rather, individual profit was tied to national gain. When a breeder was convinced “that a change of breed will suit his pasture, and be more profitable than the one he is accustomed to,” Sinclair claimed, everybody benefited. The grazier “derive[d] more advantage by purchasing that sort” for fattening, and the butcher from a “carcase … much in request with the customer he serves.” The consumer benefited from a supply of superior meat “in point of taste and flavour,” the currier from a “pelt or skin [that] … answer[ed] his purpose better,” and the manufacturer, for whom “the wool of the breed recommended can be worked up into better cloth, for which there must always be a greater demand, and a better price at the market.”98 Such a dense web of connection between production, industry, and consumption enabled improvers to argue forcefully for the broad social and political weight of their undertakings.

For some engaged in the work of improvement, providing food for Britain’s growing population was of the utmost importance. Thomas Rudge held that “profit to the breeder, and produce to the consumer” were “the two grand objects” of improvement, and in the case of sheep, never should the improvement of wool come at the expense of “the increase of mutton.” It mattered little to the farmer, he argued, whether his profits came from coarse or fine wool, or “whether his stock consists of large or small carcases,” so long as they could be made “equally ready for the market.”99 But it was “of material consequence, both to him and the public, that the greatest possible quantity of meat, with a reasonable proportion of fat, should be fed on a given quantity of land.” Any other consideration, Rudge argued, “should yield to the supply of that produce which affects the support of life.”100

The strength of these claims was such that, over time, Britishness became instantiated in the flesh and forms of these breeds themselves. Increasingly, it was what differentiated the British from other peoples. The association between national identity and beef-eating has a long and robust history, predating even the idea of Britishness itself. Steven Shapin has demonstrated the strong analogic connection between beef and Englishness by way of Galenic dietetics in the early modern period.101 Growing focus on distinctive breeds throughout Great Britain strengthened and added nuance to this association between beef and national identity. By the mid-nineteenth century, a writer for Chambers’s Journal attributed Britons’ greater stature, strength, and “physical superiority” over the French to their “better supply of Butcher-meat,”102 and by the close of the nineteenth century, even their foreign rivals recognized the British national talent for producing (and consuming) meat, and more than this, their ingenious ability to instantiate these traits in the very form of their domestic animals. According to one French agriculturalist, the English fondness for “roast meat” showed in the “prominent loins … [and] small flaccid rump” of English breeds, while the “prominent and spacious” rear of the typical French breed spoke to the appetite in France for “pot-au-feu.”103 Consuming meat made Britons British. Without a steady supply of quality meat, boosters argued, “ ‘John Bull’ would soon become as watery as a turnip.”104

The formation of a national taste for meat supported, and was supported by, the homogenization of breeds, itself achieved through the dissemination of improved varieties. By 1870, William Brown could write that “so much have pure breeds”—referring to the old, regional or local varieties that predominated at the turn of the nineteenth century—“become now intermixed, not only with each other, but with each other’s crosses” that an entire volume “on the subject was warranted.”105 However, improvement had its limits, and very often the success of an introduced breed was constrained by regional climatic and environmental factors. As Brown wrote, “All improvements invariably radiate from a centre, but they do not flow equally in all directions—the soil, altitude, rainfall, and temperature, in the case of agriculture, together with man’s prejudices, tending individually and in combination to turn aside or altogether dam up the regular flow.”106 The distribution of breeds, no less than other agricultural improvements, “has also been regulated by these influences.”107

These limits held for both improved and unimproved varieties, and became increasingly evident as the influence of the New Leicester Longwool spread beyond its home county. Even for a breed like this one, that had “been made for the country, and not the country for it,” certain circumstances were not wholly conducive to its thriving.108 Some “respectable farmers” in Cornwall, for example, “still doubted … whether sufficient advantages have been derived by their introduction,” despite the relatively long use of the Dishley breed in that region. They reported that “the stock produced by the cross” did not thrive—they were “deficient in wool, particularly under the belly,” they “lamb[ed] with difficulty, and [they were] bad nurses,” all classic signs of what contemporaries called degeneration. Moreover, they were “too tender for the wetness of the climate” and “also liable to the foot-rot,” a common complaint among breeders occupying fens, marshes, and wetlands who introduced exogenous breeds to their humid pastures.109 As Brown put it, “even with good food, sheep cannot lay on mutton when their bed is wet and cold.”110 At the other climatic extreme, Improved Leicesters were found eminently unsuited for higher elevations. Though this breed boasted the greatest geographical range of improved breeds, its “distribution is the one with least limit of elevation”—the “alluvial plains and sandstones … claim the whole of the Leicesters of England,” their “altitude limited by 700 feet.”111 “Nothing can be more absurd, or preposterous,” declared John Sinclair in allusion to the Dishley breed, “than to suppose that a fat animal, incumbered with a great quantity of wool, can ever be calculated for a hilly, and far less for a mountainous district.”112

The effect of climate was such that even improved breeds could not wholly transcend their local origins. In some cases, this meant that “improvement” acquired a distinctly local cast. This was particularly true for Southdown sheep, a class adapted to the “peculiar habitat” of the chalky hills of the southwest of England and that underwent improvement in the early nineteenth century.113 Despite the best efforts of their improvers, they retained “the tinge of their origin, which still adheres to them, [and] gives them a hardiness that would otherwise be remarkable.”114 Indeed, “So much do these sheep keep to the lime, that it may be safely said, were there more arable surface on the Down hills, or a much greater depth of other soil not of a chalky nature, the breed of sheep would have to be changed—probably to the Leicester.”115 So close was the relationship between the Southdown’s character and its native soil that the son of its foremost improver, T. Ellman, claimed that, were the breed removed to Leicestershire, “the fine flavour of Southdown mutton may be changed in time to the coarse, tallowy meat of the Leicester or other long-woolled sheep. Nor will the flesh alone be interfered with, but the wool and every other feature will become assimilated to those of the natives of the different localities.”116

The persistent tie between locality and type, even after the application of improved methods of breeding, also meant that the Southdown, when it did circulate, disappointed. F. Boys reported in the Annals of Agriculture that farmers in the neighborhood of Hillinton, Norfolk, in the east of England, some distance from the home territory of the Southdown, found the improved Southdown unsatisfactory. They were “too tender for this country, the land here being too open for them,” these farmers reported, although Boys claimed that such objections were “ridiculous!,” given that Ellman’s own flock of 500 ewes, grazed on the Southdowns, produced 620 lambs in one season on land “as much exposed, and as open, as any lands can possibly be.”117 Despite these protestations on behalf of the breed, and although its productivity (measured by per capita meat and wool outputs) increased, the Southdown’s range did not extend far beyond its home region—at least until the conditions of imperial agropastoralism made its circulation beyond Great Britain’s shores to the antipodean colonies possible.118

The importance of compatibility between locality and type was further evident in the tendency of unimproved local breeds to languish outside of their native circumstances. Gooch saw this at work in the fens of Cambridgeshire when cattle from the neighboring county of Suffolk were tried. “An opinion prevails at Islesham that the Suffolk cow will not thrive in the fens,” he wrote, though the two locales were separated by less than thirty miles as the crow flies. A local farmer had “proof of it, by having purchased some from Suffolk, and having kept them with his other cows two years, during which they gradually declined.” The insalubrious effect of the fens on this type was confirmed when the farmer “sold them [back] to the person of whom he bought them, and they were soon restored to their original health.”119

Southdown sheep. From David Low, Breeds of the Domestic Animals of the British Islands, Volume 2, Plate 14. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

This Cambridgeshire farmer’s experience was a lesson that colonial breeders would learn again and again in the second half of the nineteenth century as they worked to adapt livestock bred for the various conditions of the British Isles to the dry heat of Australia, the long winters of western Canada, or the steep hillsides of New Zealand.120 Breeds produced for one set of circumstances were not always suited to another: “the physical character of a country”—its soil, temperature, rainfall, and vegetation—had “marked influences” on the variety of kinds of livestock, “not only on those introduced from different habitats, but even on those whose constitutions have been long inured to the particular ranges where any change of climate may be brought about.”121 The natural aptitude of domesticated populations to alter in response to external conditions—be they “natural forces,” deliberate selective influences, or some combination thereof122—was the very mutability that improvers used to reformulate their breeds for higher output in the late eighteenth century, inducing their stock to reach maturity more quickly, and to achieve greater extremes of woolliness or fleshiness. But in the colonies, adaptation to novel environments would be interpreted as a loss of control over the character of their breeds, and perhaps most worrisome, as a loss of Britishness.