CHAPTER TWO

Much Ado about Mutton

In the early years of the nineteenth century, a spirited and sometimes ugly debate broke out in the pages of the Commercial and Agricultural Magazine, one of Britain’s foremost agricultural periodicals. This debate concerned merino sheep—a breed native to Spain that had been introduced to the British Isles during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Then, as now, merinos were reputed almost the world over for their exceptionally fine wool—wool so fine, in fact, that when compared with that of other breeds, it “appears as silk,” as the eminent agriculturist Arthur Young enthused in the late eighteenth century.1 The “extreme beauty”2 of this valuable article was indisputable, yet the breed’s arrival in Great Britain was controversial: its form and flesh were no match for the excellence of its fleece, and even staunch proponents of the merino like the famed naturalist Joseph Banks, who was one of the breed’s most elevated and most prolific supporters, had to admit that the shape of these animals left something to be desired. In 1800, he conceded that “their carcases were extremely different in shape from that mould which the fashion of the present day teaches us to prefer.”3 That fashion was for rotund, barrel-like proportions, best exemplified by the New Leicester Longwool or Dishley breed. This animal represented the pinnacle of British sheep-breeding, and was almost universally admired as “[a model] of symmetry and good form.”4 But where the Dishley had been carefully honed to embody a very particular combination of stoutness and delicacy—designed to produce the maximum quantity of fat and flesh upon the minimum of bone and offal—the merino seemed to be all waste. Their “outlandish forms” were the antithesis of the ideals of profit that governed British sheep-breeding. They were long-legged and narrow-chested, with low hindquarters and horns so “prodigious” as to give the rams “an unsightly appearance in the eyes of those who have been accustomed to hornless sheep,” a category that included many “improved” British breeds.5

Disagreement over the merino’s introduction to Great Britain pitted supporters of the Spanish interloper—most of whom hailed from the landowning classes—against champions of the New Leicester Longwool. The ensuing debate was protracted, the first clash erupting in 1802, and the last battle over the merino—in the pages of the agricultural press at least—only subsiding in 1812. Controversy in this particular publication was common during the decade in which the merino debate raged: contributors regularly debated the relative merits of various agricultural implements, fodder crops, and systems of management. Few other topics, however, seemed to generate quite as much prolonged vituperation as the merino controversy. As early as 1802, a proponent of the Dishley breed writing under the name “Practicus” asked, “Can a farmer ever hope to pay his rent with a flock of deformed, unthrifty, diminutive sheep, and a few tods of bastard wool?”6 Caleb Hilliar Parry, the author of a well-reputed treatise on sheep-breeding and anatomy, declared these claims “gross misrepresentations and illogical conclusions,” and called his interlocutor “flippant, declamatory, dogmatical, and expressive of the most profound ignorance.”7 Later salvos in the ongoing battle were even more hostile. When John Hunt of Loughborough sparked another round of poison pen letters to the Agricultural Magazine in August 1808 by calling the merino “high shouldered” and “hollow backed,” the “blind zealots of the Merino cause” retaliated, insulting Hunt’s views as “insipid and pointless inanities,” his favored breed as “living Dishley oil barrels,” and he himself in unflattering terms as “the doughty defender of Dishley blubber.”8

Merino ram. From William Youatt, Sheep: Their Breeds, Management, and Diseases.

The unusual duration of the controversy, and the extreme vilification of men and sheep alike that it produced, suggest that the debate cut to the quick of more issues than those merely concerning livestock breeding in Britain. Because this episode played out against a geopolitical backdrop of nearly endemic warfare with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, ongoing conversations over the relative importance of climate, heredity, and human influence in livestock breeding took on added urgency with respect to naturalizing merino sheep in Great Britain. France’s aggressive expansionism on the European continent continually threatened Britain’s access to Spanish merino wool during this period, making the establishment of a domestic source of fine merino wool seem even more pressing from one point of view. The very specter of prolonged war, however, only affirmed for the merino’s opponents the paramount importance of British food security, which, they claimed, rested on propagating New Leicester Longwools—not merinos—as the most efficient converters of feed into fat mutton. Thus, debate over attempts to establish the merino in Britain finally came down to the question of whether to breed for British meat or Spanish wool, an inherently irreconcilable pair of aims not only because of the recognized difficulty of selecting for fleece and flesh at the same time but because they ultimately demanded that the merino conform to the cultural and economic conditions of British breeding in the first place, while resisting the effects of environment and climate on its wool in the second.

Each side of the controversy professed to have the interests of the nation at heart, but what these were, and how they were best to be defended, were debatable. As opposing sides rallied around their chosen breeds, the intersection between class affiliation and competing visions of political economy were laid bare. Elite agriculturalists—the landed gentry who dabbled (or more than dabbled) in agricultural improvement—promoted domestic fine wool production and the consequent profits of industry as the key to national stability, while on the other side, professed “practical farmers” argued that securing the sustenance of its population with domestic mutton production was of paramount importance. In their efforts to encourage the breed, merino enthusiasts tried to have it all, taking advantage of fluid understandings of heritability and environmental influence to suggest that the combined influence of selection, crossbreeding, and the climate of the British Isles could improve both the merino’s form and flesh without deteriorating its wool. But these were ambitious claims, and perhaps too sanguine, at once overestimating the skill of British breeders and underestimating the degree and significance of the creolization that attended the merino’s naturalization in Great Britain.

Fleece versus Flesh

Why Great Britain should need to import and establish an entirely new breed for the purpose of growing fine wool, given the widely held belief at the turn of the nineteenth century that the British Isles were uniquely suited to the growth of sheep and wool, and the prevailing certainty that the ovine products of Great Britain were “the best in the universe,” puzzled some contemporaries.9 Since the Middle Ages, the wool of native British breeds like the “Old Herefordshire” or Ryeland breed had been widely exported, and were highly renowned throughout Europe. By the seventeenth century, though, the Spanish merino had surpassed British shortwool fleeces in volume, value, and fineness. Even Britain itself had come to rely on Spanish superfine: the shawls and broadcloths manufactured in Gloucester, Wiltshire, and Somerset relied on a blend of native and merino fine wools for their value as luxury export goods.10 Part of this reliance, ironically, was due to the same processes of improvement that had produced the merino’s ovine rival, the New Leicester Longwool. As Bakewell and his acolytes solidified the ability of native British breeds to produce succulent fatty joints, mutton superseded wool in significance for perhaps the first time in the history of British sheep-breeding. More and more, as meat production took precedence over wool, attention to the carcass—its shape, its symmetry, and the rate at which sheep reached maturity—increasingly came at the expense of the quality of the wool. Breeding for wool and breeding for meat seemed, to contemporary experts, to be largely incompatible aims, and as mutton and lamb gradually assumed precedence in much of the realm of British sheep-breeding, the quality and often the quantity of wool produced declined.11

But if the British increasingly bred for meat at the expense of wool, their Spanish counterparts put nothing before the growth of the merino’s golden fleeces. Until the third quarter of the eighteenth century, outside Iberia little was known about the sheep that produced Spain’s famous wool, or their management, despite the wide availability of their wool throughout Europe.12 As a form of live capital, sheep (like other species of livestock) have the inherent ability to reproduce themselves, imparting their characteristics, whether the capacity to produce fat mutton or fine wool, to their offspring.13 The Spanish crown rightly recognized that its stake in the international wool market rested on maintaining a firm monopoly on the production of fine merino wool by exerting strict control over the reproductive capacities of the breed. Its monopoly, therefore, depended on the ability to contain this generative capacity of the sheep—the same “spirit of monopoly which prevail[ed]” in Bakewell’s restrictive terms of letting.14 In practical terms for Spain, this meant tight control over the export of live animals, which was governed by the strict laws of the Mesta, an arcane and secretive corporate body that oversaw all aspects of the production of sheep and wool in Spain.15

However, by the mid-eighteenth century, Spain’s monopoly on both the wool and the animals that grew it began to falter. The persistent efforts of agricultural emissaries, spies, and diplomats began to pierce the veil of mystery that had shrouded the sheep and their management. Early reports from Iberia, like the “Account of the Sheep and Sheep-Walks of Spain” addressed to the naturalist Peter Collinson and published in 1764, circulated widely.16 Foreign interest centered on the transhumantes—the seasonal journeys undertaken each year by flocks ten thousand strong. Under the watchful eye of the Mesta, and according to an “itinerary … marked out by immemorial custom,” these megaherds perambulated from winter lowland pastures to the Alpine regions of Leon, Castille, and Arragon and back again.17 These peregrinations were necessary, Collinson’s interlocutor (and others after him) believed, to produce the “short, silky, white wool” for which the merino was known: Spain’s stationary flocks, like those of Andalusia, “who never travel,” had “coarse, long, hairy wool.” A “life in an open air of equal temperature,” he claimed, was the key to the merino’s fine wool, and accounted for the elaborate efforts expended in shepherding them to and from their high-altitude summer pasture in flocks “as well regulated as the march of troops.”18 Without these seasonal migrations, “if the fine wooled sheep stayed at home in the winter, their wool would become coarse in a few generations.” By the same logic, this gentleman reasoned that if Spain’s stationary “coarse wooled sheep travelled from climate to climate, and lived in the free air, their wool would become fine, short, and silky in a few generations.”19 This reasoning resonated with British breeders’ experience and observation of the diversity of their own kinds of stock, and with other early French accounts of merino management in Spain, this account helped to solidify the sense of connection between climate and fine wool—a persistent one that would dog the merino into the nineteenth century despite repeated attempts to disprove it.20

At the same time that such reports began to circulate outside of Spain, so too did the sheep themselves. As Spain’s political might waned, both in Europe and in its American colonies, merinos came to constitute valuable diplomatic capital for the Spanish crown, and were a much-desired object of political exchange. At one time, nearly all the merinos of Spain had been the property of the monarch, but “various exigencies of state,” the author of the “Account” explained, had gradually “alienated by degrees the whole grand flock from the crown,” dispersing them among the nobility of Spain.21 The first merinos to move beyond the bounds of Iberia were those acquired by Sweden in 1723, “with the view of improving the wretched Swedish breeds,”22 but after this early start virtually no live sheep left the Iberian Peninsula until the 1760s. The generous gift of 100 rams and 200 ewes bestowed on the prince of Saxony founded the largest and most esteemed flock of merinos outside of Spain, and in 1786 Louis XVI of France acquired a sizable seed stock to establish a flock at Rambouillet outside of Paris that soon attained considerable celebrity as exceptionally fine studs.23

A pair of merino sheep. From David Low, Breeds of the Domestic Animals of the British Islands, Volume 2, Plate 12. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

Britain, too, was eager to receive its share of Spanish sheep, but was “one of the last powers who turned their attention towards this national concern,” not least because confidence in the “vast superiority” of its own British woolens had made acquiring the foreign breed seem unnecessary.24 Once Sweden and Saxony had demonstrated the utility of home-grown merino sheep, Britain chose not to await the magnanimity of the Spanish monarch, instead acquiring a small population from the Estremadura region by way of Portugal in 1787.25 This extraction—at best of dubious legality, and at worst an act of outright smuggling—was followed only a few years later in 1791 by a royally sanctioned gift of thirty-five ewes and five rams of the Marchioness Del Campo Di Alange’s Negretti flock, “the reputation of which, for purity of blood and fineness of wool, is as high as any in Spain.”26 This “treasure” (“for such,” Banks assured the Board of Agriculture in 1809, “it has since proved itself to be”)27 became the foundation of George III’s royal flock at Kew.

Royal Sheep

The origins of the merino’s introduction to Great Britain were thus considerably elevated: this royal flock (a small collection of animals by any measure) became the primary stud stock for the breed’s propagation in the British Isles. Such exalted beginnings helped ensure that the bedrock of enthusiasm for the breed would be the landed gentry. Efforts to acclimatize merino sheep in Great Britain, both practical and rhetorical, were driven by these upper echelons of rural society, and it was they who largely absorbed the cost—measured in guineas and pounds sterling as well as in the evident although debatable degeneration of the royal flock—in the early phases of the breed’s acclimatization. The utmost efforts were taken to ensure the success of the breed in Britain. This meant both safeguarding its purity—under Banks’s supervision, “Farmer George’s” flock was carefully “guarded against all danger of the admission of impure blood”28—and distributing it to the most worthy stewards. During the early years of the flock’s existence, the monarch magnanimously bestowed animals on those agricultural worthies willing to undertake the experiment of their cultivation for the nominal charge of only a few guineas. Over time, as “the carcasses of the sheep … evidently improved” and their wool “rather gained than lost in value,” as Banks claimed in an 1802 report on the royal flock, the fixed price of these animals was raised to six guineas for rams, and two for ewes.29

Beginning in 1804, in admission of their increasing value, and as a “means of placing the animals in the hands of those persons who set the highest value upon them, and [were] consequently the most likely to take proper care of them,” the royal merinos were sold by auction.30 In July of that year, in spite of “heavy and almost incessant rain” and rather alarming defects among the sheep for sale, the first royal auction of merino sheep, held at Kew, was well attended, and the commerce brisk and profitable.31 Bidding was opened by John Macarthur, a pioneer of Australian settlement who attended the auction to procure stock for the recently claimed colony of New South Wales. In the first transaction of the day, he expended more than £6 on a single ram, despite the fact that it was, in the polite terms of the Agricultural Magazine, “labouring under a temporary privation of sight.”32 Healthier rams fetched as much as thirty-eight guineas. Would-be breeders were undeterred by such apparent signs of degeneration among the king’s animals. High prices and willingness to overlook the stock’s defects were signs of enthusiasm for the breed. One sheep described as “at present blind” still fetched more than twenty guineas, while another suffering from foot rot—a common ailment produced by wet conditions, and to which merinos were particularly susceptible—made £12.33 The popularity of the animals was further signaled by the haste of newly minted merino owners to spirit home their purchases. As a writer for the Agricultural Magazine reported in the following month’s issue, one gentleman, having failed to arrange prior conveyance appropriate for an ovine cargo, rode off with his newly purchased sheep as a passenger in his chaise, “such was the eagerness of [these] buyers to bear off their lots.”34

Improbable as it was, this scene repeated itself at the following year’s sale, where, once more despite the apparent shortcomings of the breed in general (even its fiercest promoters in Britain acknowledged that merino sheep were “very far from handsome in their shape”),35 and the king’s flock in particular (high mortality from disease among the stock sold in 1804 “had been hinted at” by that year’s purchasers),36 commerce in 1805 only increased. In the opening sale of the day, a shearling ram “of the worst appearance of the whole” sold for more than £22. Handsomer animals followed, reaching prices as high as sixty-four guineas in one case.37 As new owners loaded their purchases into carts “with an enthusiasm of the most laudable kind,” one especially eager buyer was seen “helping a ram into a carriage!” and, as he was “a man of fashion,” the “scene of business presented a picture of the greatest hilarity.”38

These instances speak not only to a willingness to overlook the possibly negative effects of British climate and conditions, or to the growing passion for merino sheep in Britain in the early years of the nineteenth century. They reveal the degree to which this enthusiasm was a freak of the upper classes.39 Merino breeding was an elevated art. The breed’s proponents hailed from the highest orders. Even its humbler champions were landed farmers influential in important breed societies of the day. Benjamin Thompson, Caleb Hilliar Parry, George Tollet, and Nehemiah Bartley, for example, all had close ties to the exclusive Bath and West of England Society. Among the breed’s more lofty enthusiasts, John Southey Somerville (the fifteenth Lord Somerville) possessed, in addition to his title, the means to undertake his own merino-buying expedition to Iberia. Following “the example of his Sovereign,” Somerville sailed to Portugal in 1798 “for the sole purpose of selecting by his own judgment, from the best flocks in Spain, such sheep as joined in the greatest degree the merit of a good carcase, to the superiority in wool.”40 This costly undertaking resulted in “a flock of the first quality” and the approbation of his peers.41 Joseph Banks applauded Somerville’s initiative as an act worthy of “the highest commendation.”42 Indeed, any who undertook to experiment with merino sheep—“all,” as Banks put it, “who honour the Fleece”—were, in the eyes of the breed’s supporters, patriots of the highest order.43

Patriots, For and Against

Honoring the fleece rather than the flesh of these animals signaled a particular stance on the political economy of the nation. Each side of the merino debate claimed to be acting according to national interest, although they differed in their interpretations of what that meant in terms of ovine economy. For proponents of the merino sheep, it was in Britain’s best interest to ensure a favorable balance of trade by securing the continued production of luxury articles for export. They couched their arguments in terms that linked the domestic production of fine wool to the patriotic defense of British industry and crucially, in light of Britain’s ongoing conflict with France, to independence from foreign trade. Worry over economic dependence on foreign supplies had been growing toward the end of the eighteenth century. Modern estimates suggest that British demand for Spanish wool had grown by a factor of sixteen over the course of the eighteenth century,44 but access to this article fluctuated during the Continental wars. Imports of Spanish wool ranged between 2.1 and 4.1 million pounds in the late 1790s, but rallied to an average of 6.5 million between 1800 and 1806. In 1807, Britain imported an astonishing 10.5 million pounds before that figure plummeted to only 2.1 in 1808. Thereafter, volume continued to vary but never sank below 4.6 million until the close of the war.45

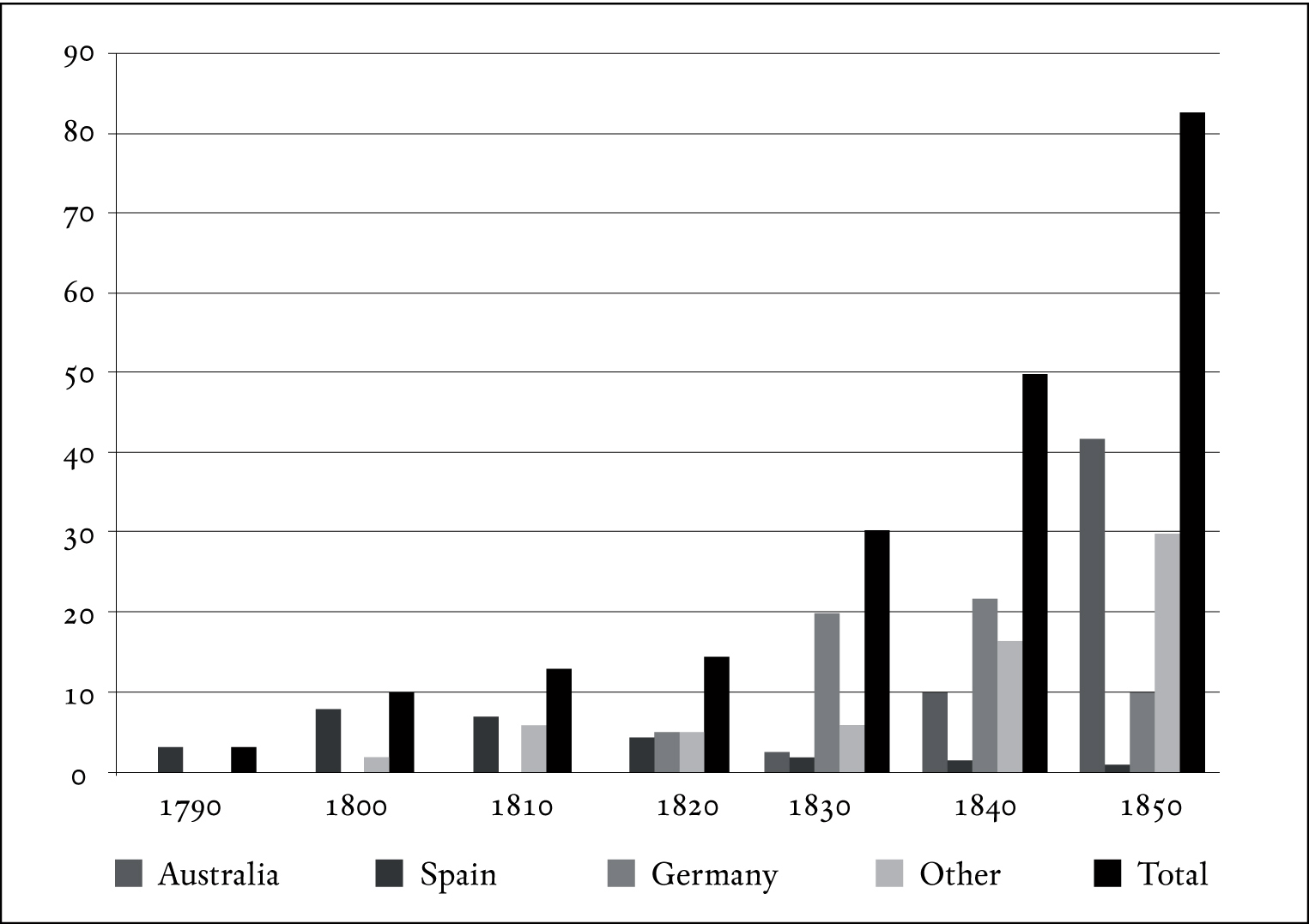

British wool imports in millions of pounds, 1790–1870.

Values are estimates, and are compiled from Mitchell, Abstract of Statistics, 191–93, and Carter, His Majesty’s Spanish Flock, Appendix, fig. 8.

These erratic swings were a cause for major concern. Somerville gave voice to this growing unease when he warned the Board of Agriculture as early as 1799 that “the political situation of Spain may be such, as to shut out, or at least materially increase the present difficulty of importing her wool into this country; in which case, it is a matter of the utmost national importance, that the fine woollen trade of Great Britain should suffer nothing in reputation.”46 Such concerns seemed all the more pressing after 1807, when France both extended its naval blockade against Britain to neutral ships and invaded Spain.47 To hear the breed’s proponents, it seemed that Napoleonic France’s sole aim in over-running Europe was to gain a monopoly over the trade in fine wool at the expense of Great Britain. Thomas George Bucke, secretary of the Merino Society (est. 1811) from 1812 to 1813, believed France’s nefarious maneuverings were undertaken with the “object to make that country the emporium of superfine wools” at the expense of British industry, while Banks urged his compatriots to “resist the baneful machinations of our persevering and implacable foe” by actively encouraging the merino in Britain.48 One of the first acts of the Merino Society after Banks convened it in 1811 was to translate a report on the propagation of the merino from the Minister of the Interior to Emperor Napoleon. The contents of this report, originally published in Le Moniteur, detailing plans for the establishment of ram depots and a breeding schedule to bring the population of merinos in France up to eighteen million, only confirmed such fears of Britain’s “subtle and inveterate enemy.”49

While the acquisition of merino sheep was not the foremost object in the belligerence of France, nor a monopoly over merino wool the primary aim of its blockade or of the more comprehensive Continental System designed to exclude Britain entirely from the commerce of Europe, its military machinations and expanding power did have a perceptible and important impact on how, and particularly on where, merino sheep were raised. Most significantly, it eroded the long-standing embargo on the export of live sheep from Iberia. By 1812, it seemed Somerville’s dire prediction had come to pass: France—Britain’s “implacable foe”—controlled the lion’s share of European merinos, and prominent agriculturalists and economists feared that Britain’s dependence on the importation of Spanish merino wool would reduce the nation to a “tributary to France for a supply of that article.”50

The plight of the Spanish merino was indeed severe; with Iberia a major theater in the ongoing conflict between France and Britain, “contending armies … traversed the ancient walks of these animals, marking as their prey, and destroying for their food, every flock which they found upon their march.”51 By 1812, Spanish flocks had been drastically reduced: an estimated three-fourths were “already destroyed, and the remainder daily diminishing by rapine and neglect.”52 Not all Spanish merinos in the path of the French army were devoured or destroyed, though. Considerable numbers were rather spared “the rapacity of the French,” and French occupiers found themselves free to disperse the remnants of Spain’s massive merino flocks as they saw fit. The agents of French, German, and American interests fell over this ovine war booty, while Britain, as the sworn enemy of the French, suffered exclusion from the buying frenzy. Not only was Britain’s own wool supply threatened, but, it seemed, her enemies were siphoning off all the valuable merinos from the peninsula. As Benjamin Thompson lamented, “a considerable portion have found their way into the vast tract of European territory under the controul of our inveterate enemy,” while “a further number have been conveyed across the ocean to America, and other distant regions.”53 Despite a recent royal “gift” from the Spanish crown in 1809 of 2,000 sheep from among the famed Paular flock, and the fact that Great Britain had managed to spirit away as many as 10,000 merinos by way of Portugal during the frenzy, the lack of reliability in what Britain could expect to import continued to weigh heavily.54

Members of the Merino Society thus viewed the task of establishing the merino in Great Britain with the utmost gravity and a sense of national consequence. The Society brought together noblemen and other agricultural worthies on explicitly nationalistic terms, as “a body of Britons combined in association for a patriotic purpose.”55 For these zealous improvers, patriotism began at home. Somerville took the lead in 1799 when he vowed “as an individual, bound in a particular manner to support the agricultural produce of my own country … never again to wear superfine cloth, or kerseymere, any part of which shall be of foreign growth.”56 Lest critics accuse the Society’s well-heeled dignitaries of supporting the production of a mere luxury item for their own comfort at the expense of the availability of “animal food,” which “an increasing population imperiously calls for,” Banks and the other members, “the rank and number … [of whom were] commensurate with the great importance of the object,” continually stressed the “great national as well as individual advantage” that would derive from their activity.57

Not all patriotic agriculturalists understood their national sentiment in the same terms. Those who opposed naturalizing the merino in Britain also claimed to be acting in the best interest of the nation, but for them, patriotism meant breeding British and eating British, as well as wearing British.58 John Hunt, the “Leviathan of Loughborough,” led the charge against the Spanish breed. As a patriot of the “old-fashioned kind,” he held that the “Leicestershire breed of sheep [was] a subject of national importance,” and moreover that “truly patriotic views” meant a dedication first and foremost to feeding Britain’s growing population.59 No breed was better suited to this task than the New Leicester Longwool, its advocates asserted. A correspondent to the Agricultural Magazine writing under the name “Pastorius” rallied to Hunt’s call between 1804 and 1806. He argued that the value of the Dishley breed was its ability to produce “a much greater quantity of mutton … on proportionably less food” than any other breed, making it the most efficient means of increasing the food available to a growing population without recourse to additional acres.60 Moreover, Dishley mutton was of such extreme fatness that the laborers who constituted its “principal consumers” obtained “a much greater quantity of food from a pound of Leicester than from an equal weight of small mutton” in the form of broths and drippings as well as flesh.61

Demography, not the balance of trade, lent urgency to this side of the debate. Fredrik Albritton Jonsson has shown how certain Scottish Enlightenment thinkers in the eighteenth century saw the imperatives of improvement (read: enclosure) in conflict with the need to maintain a healthy rural population in the Highlands—a particularly critical concern during the Seven Years’ War when Scottish Highlanders helped fill the ranks of Great Britain’s army and navy.62 The merino debate echoed these earlier concerns, but in this case the contest between improvers and populationists moved indoors to sit at the table. Great Britain’s population was growing in the early nineteenth century, and as John Hunt argued, “it is on our increasing population that we must depend for our national protection and support, and without a proper supply of animal food it would be impossible that our present state of population should be maintained.”63 Because the “pitmen, keelmen, and coal-heavers at Newcastle, Shields, and Sunderland, consume[d],” according to Pastorius, “a much greater quantity of mutton, individually, than any other men in the world,” it was of the utmost consequence that the “extremely handsome, fat, and profitable sheep, the New Leicester,” be granted “a peaceable existence.”64 But merino supporters refused to concede that their favorite breed posed a threat to the working-class food chain. Much like its wool, merino mutton was better fit for the table of a gentleman than for that of a common laborer. Thompson, perhaps exasperated by Hunt’s proclamation, replied, “Let the Leicestershire still supply the labouring classes with the lard, of which so little goes a long way.” The “naturalized Spaniard,” meanwhile, would “furnish … meat, of far superior quality for the tables of the more wealthy” without any threat to Hunt’s champion breed.65

True Spanish Wool

In fact, the project to naturalize merino sheep demanded much more than merely a peaceable existence for the Dishley. In the first place, for the effort to succeed, the animals had to retain the quality of their fleece, upon which their worth was evaluated. By and large, contemporaries understood this to be a matter of the breed resisting the influence of the climate and environs of the British Isles. At the same time, the dominant trend in British livestock breeding was to select for meat. Thus for the Spanish sheep to maintain their place on even the gentleman’s table, the cultural climate demanded that they shed some of their foreign character and take on qualities of the English. This was to be accomplished through selective crossbreeding: by pairing merino rams with native ewes, and subsequently selecting from among these offspring, enthusiasts proposed to eventually establish a breed of “Anglo-merinos.” By this “art of breeding,” given time and “careful and judicious selection,” these “Spaniards” could become more English.66 The goals of British breeders were thus coterminous with the process of naturalization; they were to produce “a new race of sheep of their own making,” one “with Spanish fleeces and English constitutions.”67

Such a plan had the double virtue of improving the wool of native British sheep, while ameliorating the shape of Spanish breeds. But crossbreeding is always a risky proposition. Opponents worried that by these efforts, the merino would pollute British stock. As any type “invariably … propagate[s] its kind,” wrote one anonymous Scottish improver in 1774, “if any one species be mixed with any other, the progeny will invariably be a mongrel breed, participating alike of the qualities of both the father and mother.”68 Sir John Saunders Sebright put an even finer point upon it. Even “if it were possible, by a cross between the new Leicestershire and Merino breeds of sheep, to produce an animal uniting the excellencies of both, that is, the carcase of the one and with the fleece of the other,” an animal “so produced would be of little value to the breeder” since “a race of the same description could not be perpetuated.” That is, a cross between two such different types would never breed true, and therefore “no dependance [sic] could be placed upon the produce of such animals; they would be mongrels, some like the new Leicestershire, some like the Merino, and most of them with the faults of both.”69 The attempt to improve domestic wool by crossing British breeds with Spanish sheep, they feared, would end by diminishing the excellence of British flesh and form.

Added to this, those aligned against the breed were convinced that it would degenerate in the foreign environment of the British Isles. Agriculturalists and breeders outside the Society, some prominent among the ranks of early-nineteenth-century improvers, doubted the breed’s ability to withstand the harsher climate of England without sacrificing the quality of its wool. Indeed, climatic concerns and environmental unsuitability, unsurprisingly, were among the irrepressible John Hunt’s primary objections to merinos. He firmly believed that “animals will best preserve their character on their native soil.”70 Following the same logic as Collinson’s correspondent a generation earlier, he argued that if merinos were transposed to Leicestershire, for instance, “in a few years the nature of their offspring would become subservient to local circumstances, even if no crossing had taken place.” This meant, in effect, the loss of the merino’s character: “the carcase would improve, and the wool become coarser,” thus negating the very justification for importing merinos, namely, the superior quality of their wool.71 “If fine wool be the object,” Hunt claimed, “it will not be sufficient that we go to Spain for Merino sheep; for if the character is to be preserved, it will also be necessary to bring the climate, soil, and pasturage with them.”72

Conceptions of breed identity that privileged the effects of climate above all else increasingly came under challenge. The Scottish improver quoted above observed, for instance, that “many parts of England enjoy a climate similar to that of Hereford.” If climate was indeed the determining factor in a breed’s character, the sheep (and their fleeces) in these places would naturally resemble the Ryeland, “yet wool of an equal quality is not to be met with there.”73 Even more to the point, the kind of metamorphosis Hunt feared, his detractors argued, was impossible in the absence of crossbreeding, deliberate or otherwise: “As to foreign animals assimilating with the breed of the country into which they may chance to be introduced, without intercopulation or crossing,” proclaimed a gentleman whose pseudonym (Cultivator Middlesexiensis) betrayed his metropolitan place of residence, “it is a gross deception, and has been repeatedly so proved by a long chain of facts.”74 Indeed, it was precisely such unsanctioned “intercopulation” that gave rise to the popular misapprehension of the role of climate, in the view of those who argued for the paramountcy of inheritance. As the anonymous Scotsman noted, “When a small number of any strange sheep comes into a different district, where there is a breed differing from themselves in any respect, … it is impossible, by any ordinary care, to keep them from intermixing with the native sheep.” Subsequent generations “necessarily approach[ed] … the nature of the sheep with which they are intermixed; [thus] … it must of consequence follow, that, after a few generations, they will have so far lost their distinctive marks as scarce to be distinguishable from the sheep with which they are now associated.”75

It is easy to see how such an outcome could be attributed to climate instead of inheritance. Before the age of steam transport sheep, like many other kinds of domesticated animals, had “little chance to be carried far from home.”76 The operation of heredity was thus apparently coterminous with the influence of local climate and environment, making it even more difficult to distinguish between the two. By the early nineteenth century, though, experience and observation over the course of generations (ovine, if not yet human) could be marshaled against this interpretation. As John Sebright wrote definitively in 1809, “It has been ascertained that neither the sheep nor the wool sustain any injury from the change of climate or pasture; and the absurd prejudice, that Merino wool could be grown only in Spain, is fortunately eradicated.”77 But he may have been overstating the case. Climatic determinism was not so easily put to bed, and continued refutations of the influence of climate and environment suggest that objections on these grounds continued to plague merino enthusiasts.

Ideas about climate operated not only against the merino’s establishment in Great Britain. They could also be deployed in favor of the breed. The handy maxim used to make sense of the diversity of native British types—that “every soil has its stock”78—applied as well to the placement of merino sheep in Britain as to a topographical taxonomy of its native kinds.79 Raised on the right type of soil, proponents of the breed argued that it would prosper rather than degenerate, and that it would do so without threat or challenge to the Dishley breed. Far from restocking the rich pastures of Leicestershire, breeders proposed improving the yield of “forester” breeds subsisting on the margins of agricultural cultivation in Britain. Often, these places were colder and more inclement than better lands used for arable farming or more intensive forms of animal husbandry, and the thickly fleeced foreign sheep seemed particularly suited to such regions. As one Nottinghamshire breeder wrote, merinos “seem extremely well calculated for our cold hilly situation: they are enclosed in a thick almost impervious coat, muffled round the eyes, and nearly to the end of the nose, and their legs down to the feet covered with fine wool of the valuable quality.”80 Breeders in Ireland and Scotland—understood to be the agricultural as well as political margins of the United Kingdom—concurred. Here, the yolk—the natural oil secreted by sheep, which on the merino saturated the fleece up to an eighth of an inch—offered what seemed a natural defense against the cold, wet climate. “The yolkiness of the Merino fleece,” suggested one subscriber to the Society residing in Ireland, “and the compactness of its surface, act like an oil-cloth for its defence against rain, and fits the animal the better to endure our wet climate.”81 Indeed, this gentleman was unable to “conceive any breed of sheep better adapted to the climate and soil of the counties of Cork and Kerry, than the Merino breed.” Though of similar stature to “those [sheep held] in common amongst the country people,” their “carcases” were “so much more round and compact, and their wool so much more capable of paying for their keep [that] add to this their thriftiness and docility of disposition,” and he would “recommend them in preference to larger coarse woolled sheep.”82 A Scottish correspondent concurred: “The situation on my farm,” he held—despite the harsh conditions of this northerly locale—“seem[ed] to agree with the Spaniards exceedingly well.”83

A pair of Exmoor sheep, or the “Forest Breeds of England.” From David Low, Breeds of the Domestic Animals of the British Islands, Volume 2, Plate 6. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

Fitting the merino into Great Britain’s finely variegated geography of sheep-breeding meant that marginal types and marginal places were far more likely to be slated for takeover by the merino than the Leicester or its territories. Few proponents of the Spanish breed felt it necessary or even advisable to cross with a long-wooled, heavily built breed like the Leicester, or to stock two such different breeds on the same pasture. Benjamin Thompson contended that as a breed “adapted only to luxurious pasturage,” he would “let [Leicesters] there revel.” The merino, on the other hand, could profitably improve marginal pastures at the expense only of the hillside breeds—smaller, hardier short-wooled sheep—not the Dishley. He advocated “the banishment of those unprofitable short-woolled animals now occupying our wolds and forests, in favour of Merino, yielding as much and as good mutton, with twice as much wool, ten times as valuable.”84 Hardly a voice was raised in defense of these “race(s) of horned mountaineers,” unlike the chorus that rallied for the Dishley, that national treasure on four hooves, presumably because their breeders were less wealthy and well-connected than the elite merino advocates.85

The salience of climatic influence had to do with the perceived value of English-grown merino wool: for this experiment in acclimatization to work, the fleece of these transplanted Spanish sheep would have to retain its fineness as well as its value. Without these two characteristics, it was merely an inferior mutton-maker in the land of fat sheep. This was why proponents of the breed like George Bucke were so invested in the claim that the “absurd prejudice, that Merino wool could be grown only in Spain,” was “fortunately eradicated,” and objections to the merino based on climatic arguments had been “practically and completely set at rest for ever.”86 According to Benjamin Thompson, the first secretary of the Society, experience “having so clearly established the practicability of growing, in this kingdom, Wools equal to the article which we have been in the habit of procuring from Spain and other countries … it would be a waste of words to dwell on it.”87 As his successor, Bucke agreed. “English grown Merino wool,” he asserted, “is proved equal to the superfine manufacture of broad cloth.” Perhaps the best evidence that “Merinos stand our climate equally well with our native sheep” rested in the opinion of the lower orders, known to elite agriculturalists primarily for their conservatism and rude ignorance. According to Bucke, “Even the common farmer, those lumps of prejudice and antipathy, seem hankering after the Merino sheep. They cannot stand against doubling quantity and price of wool in a single cross.”88 Wealthy gentlemen were known to be open to agricultural experimentation; that many among the landed classes had embraced the merino was heartening, but that it was able to win over even “the most illiterate of farmers” seemed proof indeed of its capacity to thrive in England’s foreign climate.89

But both fineness and value were contestable qualities, and in these regards the act and the outcomes of transplantation were more ambivalent than breed enthusiasts had anticipated, as those who would sell their “English grown Merino wool” discovered.90 Compared with the high price of merino sheep in Britain, their wool offered a very poor return on investment. The inability to command what merino growers deemed a fair price—one on par with imported Spanish merino wool—plagued the Merino Society during its brief existence, and its cause provoked much speculation. One correspondent with the Agricultural Magazine noted, for example, that the prices in 1809 of Spanish merino wool from the region of Seville ranged from ten to fifteen shillings per pound, while the price of English merino wool sat, in the same year, closer to eight shillings, four pence.91 The price of half-bred Anglo-merinos was even lower, despite almost unanimous testimony that even one cross improved the quality of English short-woolled fleeces. “Surely, then,” this correspondent wrote, “more might be obtained for wool of the first cross than 4s to 4s 6d per lb.”92 The perceived prejudice among English wool staplers against merino wool produced in Britain constituted one of the most serious obstacles faced by merino enthusiasts, for if they could not convince wool buyers that merino wool grown in Britain was as valuable as merino wool from Spain, they would not be able to convince British breeders to discard their Southdowns and Ryelands in favor of the foreign breed.

And herein lay the paradox of naturalization: the merino’s foreignness represented both the appeal of the breed, for it ensured the value of its wool, and the grounds for objection, for it threatened the sanctity of native British breeds. The struggle over pricing merino wool grown in Britain was about the degree to which location and environment inhered in the notion of a breed in the early nineteenth century. Whether or not merino wool did degenerate in Britain, breeders faced the belief that even if the wool were as fine as that grown in Spain, it was somehow intrinsically different, and therefore worth less on the market than “true” Spanish wool. While merino breeders held that the wool they sold really was “Spanish wool … though grown in England,” this conflict over pricing suggests, in fact, it wasn’t. Despite the impassioned claim of George Webb Hall of the Society’s Somersetshire committee that “fine wool will ever be as fine gold, so long as luxury shall exist, no matter where grown, so that it be fine wool, and brought to market in merchantable condition,” market prices continually proved him (and Banks) wrong.93 As Hall lamented, “Is there a single grower of Merino Wool in this extensive Society, or in the United Kingdom, who can report to it, that having produced fine wool, he has been able to dispose of it at a price that bears any relation to the price of Spanish wool?” This was a mere rhetorical question: among his acquaintance, there was not.94 The superior value attached to Spanish wool suggests that its exoticism rated higher than wool produced in England even though merino wool, wherever grown, usually remained finer than the finest of native English wool. It appeared that for wool to be Spanish, it must have been grown in Spain. In removing the “Spanish breed” from its native pastures, British merino breeders lost the connection to location so crucial to its value on the market. In a way, then, John Hunt had been right when he wrote that for breeders to grow Spanish wool in Britain, they would have to bring the soil, climate, and pasturage along with the sheep, although for different reasons from those he supposed: it appeared to be a question of marketing as well as strictly one of physiology. Even the limited success of acclimatization undercut the value of merino wool. Ironically, by making the merino more native to Great Britain, the architects of its naturalization introduced the seeds of their own undoing.

A Touch of Class

While the influence of climate worked against the merino with respect to its wool, adaptation to local conditions in other ways remained a requirement of the breed’s acceptance in Britain. At the same time that the wool market demanded that merino wool resist degeneration in the light of British climate and environment, the cultural predominance of meat-eating demanded that it conform to the standards of fat stock breeding of the day. This meant that the merino would have to become more British from the inside out, but it would need to do so without sacrificing the value of its wool. This was a tall order for both the sheep and the men who bred them, not least because it entailed, in the first place, overcoming the prejudice of most British breeders, which was dogged, and pertained not only to points of wool and climate but to the issue of form. “Their shape,” acknowledged Charles Henry Hunt, author of A Practical Treatise on the Merino and Anglo-Merino Breeds of Sheep (1809), “though what the greatest painters have chosen as models, is certainly not such as the English sheep-fanciers of the present day can admire.” In contrast to the famous barrel shape of the Leicester Longwools, merinos were “in general rather high on their legs, flat sided, and narrow across the loins, and consequently defective in the hinder quarter.”95 John Hunt was, not surprisingly, considerably less generous. “If we proceed from the neck,” he wrote to the Agricultural Magazine, “we shall find the Merino ram high shouldered, hollow backed, very deficient on the rump, long legs, carcase small in proportion to the height, with a weight of bone in all parts, sufficient to obliterate every appearance of perfection.”96 Other skeptics noted its narrow chest, a black mark against any animal “destined to be the food of man,” because “no animal whose chest was narrow could easily be made fat,” and the merino was “in general contracted in this part.”97

Even staunch proponents like Somerville expressed doubt as to the merino’s ability to overcome these deficiencies. For his part, if the merino failed to conform to this desired shape, the value of its wool, and, importantly, the flavor of its mutton, were such that the eye of the breeder rather than the form of the animal ought to be improved: “Supposing … that no great improvement in the shape should be obtained, it becomes to any man simply a question between his eye and his pocket; if he must have beauty, and that, too, of an unwieldy description, let him have it; but if he prefers profit … he knows where it may be found.”98 Most enthusiasts, however, retained their faith in the superlative effects of British skill and method when it came to remolding the merino. Banks believed that “in due time, with judicious management, carcases covered with superfine Spanish wool, may be brought into any shape, whatever it may be, to which the interest of the butcher, or the caprice of the breeder, may chuse to affix a particular value.”99

Claiming that merino sheep had come to Britain in an almost unalloyed state of nature was a particularly effective way to reassure audiences on the point of its potential for improvement. Denying any skill or deliberation to the tradition of stockbreeding in Spain left room for the application of British skill. When John Hunt accused the merino of existing “in a state of uncultivated nature,” he meant it as criticism, but Banks, Somerville, and the Merino Society turned it to their advantage.100 As an “unimproved breed,” an uncultivated form, the merino needed only the virtuosic eye and practiced hand of the British stockbreeder to bring it to that “extreme of perfection” to which they were accustomed.101 Spaniards, “if they may be supposed to know what we call beauty,” scoffed Caleb Hillier Parry, an esteemed member of the Bath Agricultural Society and early merino enthusiast, “have never attempted to produce it” in the form of their sheep,102 and were, according to Hall, “at best” known to be “great slovens in all their agricultural operations.”103 Their single-minded focus on fine wool accounted for many of the breed’s perceived defects. The whole system of merino husbandry in Spain was calibrated toward producing wool firstly, and meat only secondarily (if at all): it was eminently not designed to produce the kind of fat mutton so tempting to the British palate. From a British perspective the laws of the Mesta, which governed the transhumantes, and the long migrations themselves, were thus detrimental to the improvement of the breed. Somerville remarked that “it must be evident to every judge of stock, that a journey from the mountains of the north to the plains of the south of Spain, cannot be otherwise than productive of more injury to the frame and constitution of the animal, than of benefit to the fleece.”104 The Mesta only impeded “the Spaniards of attempting improvements, even if they had the disposition.”105

This, and not the true nature of the merino, accounted for the “defective form of the animals originally imported” to Great Britain.106 But much could be done to unlock the latent potential of the breed. Even its most egregious deformities could be recast as virtues. “There is an excellence peculiar to Merino sheep and their crosses, which has hitherto been little noticed,” George Bucke claimed, and this was their narrow chests, or rather (from another perspective) their relatively heavy hindquarters. According to the very Bakewellian logic of concentrating growth in the most profitable cuts of meat, he argued that because “their hind quarters are heavier than their fore quarters, … the greater weight of mutton” was concentrated “in the more profitable joints.”107 More generally, epicures asserted that together with proper husbandry, the superlative pastures of Britain would elevate the inherent potential of their flesh. “I cannot suppose,” stated Somerville, “that the flesh of sheep of the Spanish breed, the grain of which is as fine as any we are acquainted with, properly fed from the birth, and on English pasture, will not prove excellent meat.”108

Indeed, a difference in national taste for mutton could account for many of the merino’s perceived shortcomings. “Mutton in Spain,” explained Sir Joseph Banks, “is not a favourite food; in truth, it is not in that country prepared for the palate as it is in this.” His compatriots might have consumed beef in greater quantities than sheep meat, but British mutton was a work of art: “our lamb-fairs, our hog-fairs, our shearling-fairs, our fairs for culls, and our markets for fat sheep” were “calculated to subdivide the education of each animal, by making it pass through many hands, as works of art do in a manufacturing concern,” ultimately producing an object of such high quality that if “offered for sale, and if fat and good, it seldom fails to command a price by the pound … dearer than that of beef.” High praise indeed from a nation of self-described beef-eaters, whereas “in Spain,” Banks explained simply, “they have no such sheep-fairs.”109

There was no doubt that British improvers would rise to this challenge. Since “improvement in Spain seems out of the question,” explained Charles Hunt, “we must therefore look to the enterprising spirit of this country for such amelioration, either of wool or carcase, as the Merino sheep are susceptible of.” Such was his faith in the abilities of his compatriots that “the knowledge and attention of English breeders cannot fail,” he proclaimed, “to effect great improvements in both these points.”110 By and large, this meant crossing native ewes with merino rams in the hope of imparting some of the superiority of British form to an animal clad in Spanish wool. And while the Dishley was the recognized paragon of fat mutton in early-nineteenth-century Britain, few endorsed a cross between such dissimilar types. Rather, most proponents advocated avoiding such “mountebank doctrines of crossing dissimilar breeds, whom nature in its infinite wisdom had set a sunder.”111 Pairing like with like by selectively breeding merino rams with native ewes of the smaller breeds of mountain sheep seemed to provide the best opportunity for improving the carcass of the Anglo-merino without sacrificing its wool. “The effect of a Spanish ram,” pronounced Somerville, “on the fleeces of a horned flock, such as the Dorset, the Welsh (a sheep of neat frame), on the Wiltshire, the Norfolks, the Dartmoor, [or] the Scotch … will be neither more or less than a very great increase of profit on the fleece, with very little, if any, injury whatever to the form of the animal.”112 If not a cross with “those breeds of heath-croppy,” then the next most suitable cross was with another shortwool breed.113 Parry preferred the Ryeland breed of Herefordshire for this work. His own experience, he claimed, “proved from actual facts the practicability of producing in England, from a cross of Ryeland ewes with Spanish rams, and without the intervention of a single Spanish ewe, wool equal to the finest which is imported from Spain.”114 Putting only the most rotund specimens of merino ram to native ewes would bring Anglo-merinos closer to “the present fashionable ideas of beauty,” themselves the product of “many years of attentive study,”115 while leaving the longwools in their preexisting state of perfection. For the merino lobby, this promised to increase the breeder’s profit while at the same time securing Britain’s supply of wool and therefore its balance of trade, that ever-important point of political economy.

The Ryeland breed of Herefordshire. From David Low, Breeds of the Domestic Animals of the British Islands, Volume 2, Plate 13. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

Accounting for Taste

Naturally, not all who involved themselves in the debate over the merino in Great Britain were as optimistic about the breed’s transformative ability. Predictably, John Hunt had his say on this point. “If we are to resign our fat mutton” in favor of the merino, he feared, “our own fat must go into the bargain, and all for the sake of covering our lean sides with a fine coat made of Spanish wool.”116 More worrisome were the doubts about the ability of the merino to put on fat that came from more elevated corners of the agricultural world. The famous Thomas William Coke of Holkham—esteemed agriculturalist, breeder, and “a person inferior to none in respectability, real patriotism, and liberal attention to the rural economy of the British Empire”—also “declared himself unfavourable to the Spanish breed.” Such was his stature that his objections (confined “entirely to the carcase; for the superiority of the wool over the English fine wool cannot be doubted”) were enough to temporarily shake even “the good opinion” that Lord Sheffield, a vice president of the Merino Society, “had formed of the breed.”117

Yet enthusiasts of the breed were increasingly confident in their immediate, as well as eventual, success. The merino fattened as well as any native British breed, they claimed. The “Spanish breed has proved itself superior in point of size and fattening quality,” Cultivator Middlesexiensis asserted, and Spanish mutton was “the most solid, savoury, and nutritious, of any to be found in this country.”118 Hunt, moreover, could set his mind at ease as to the fate of his own fat, one unnamed proponent argued, since the “Spanish race” was apt to fatten “in an equal degree with any of our native breeds.” The “admirers of fat men and fat mutton,” then, “may console themselves, that they may procure as large, as fat, and … as well-flavoured meat, from the descendants of this breed, as the fine Leicestershire herbage has yet produced from any breed whatever.”119

Paeans to the excellence of merino mutton were sung with increasing vigor. Benjamin Thompson recounted dining on “the saddle of a Merino-Dishley wether” with “two gentlemen, who, from their elevated rank in life, must constantly have excellent mutton on their tables.” They were nevertheless “united in their praise of this joint.”120 Elsewhere he proclaimed of a Ryeland-merino cross that “better mutton was never put upon a table.”121 Similarly, albeit with more restraint, John Wright, one of Hunt’s less illustrious and therefore more restrained combatants, reported from personal experience that though “I profess myself no epicure, I dined off a saddle of [merino] mutton … and as far as my poor judgment went, thought it most delicious.”122

Perhaps most important, though, when it came to proving the mutton-making abilities of the breed, were its growing triumphs in the show pen. At Somerville’s show in 1812, for instance, Thomas George Bucke’s flock “made a conspicuous figure, not only for a fine fleece, but the promise of great size, and nearly an English form.” As one report noted, “The Merinos, indeed, appear to be improving annually in size, and assimilating more to the English shape.”123 Coke, who was well known as a proponent of Southdowns, had “stirred up a competition between the Merinos and the South Downs,” but despite having “exhibited the flower of his flock … large, and well laden with fat,” the merinos took the day. The animals that trumped his own had been “pushed to the utmost point of obesity … giving the most decisive proofs of possessing the faculty of taking on fat, and their mutton being equal, at least in point of goodness, the palm of victory appears due to them.”124 Even these merinos remained relatively diminutive, but “the superior size of the Down sheep proves merely,” this observer recorded, “that they are bigger, not better than Merinos.”125

AND YET, for all this, the merino never took hold in Britain in quite the way that its proponents had hoped. It is true that, today, it is hard to find a so-called native breed of sheep in Britain without some degree of merino present in its genotype. Essentially, this represents the long tail of precisely that mechanism of introduction and “intercopulation” described by the anonymous Scottish observer in 1774. The merino, in effect, was absorbed into the existing sheep stock of Great Britain without ever becoming established either in its pure state or in the kind of fixed crossbreed advocated by its most enthusiastic backers. Even the question of whether or not its wool lost some of its fineness in the foreign climate and conditions remained unresolved in the nineteenth century. The refusal of wool brokers to give what breeders believed was a fair price was an equivocal judgment upon the merino. It might suggest a number of things—that the wool degenerated, or that supply exceeded demand. That the merino soon became so well established in Australia, where climate and environment are more similar to those of Spain, suggests perhaps it did degenerate in Britain. The first 100,000 pounds of Australian wool reached Great Britain in 1818. By 1826 that volume had risen to 1.1 million pounds, by 1830 it had doubled, as it did again every five years until 1845—reaching 24.2 million pounds.126 By 1870, combined imports from the Australian colonies and New Zealand constituted twice the volume of wool imported to Britain from all other sources. Regardless of whether or not Australia provided a solution for the physiological problem of the merino in Britain, it almost certainly provided a solution to the cultural and symbolic aspects of this controversy. For in Australia, Britain found it could grow the vast amounts of “Spanish” wool it needed, without the impediment of hostile enemies like the French, and without threat to the sanctity and integrity of its own “native” breeds.