OUT OF AFRICA—INTO TEXAS

CHAPTER 31

There is a saying in Norway: “Never tempt the gods by being too pleased with life or they might become envious and strike you down.” On several occasions I have wondered whether there might be some truth in this maxim, such as those times we’ve all experienced when life is peachy and then all of a sudden everything around you collapses into shambles and you spend all your energy working your way back out of the mess.

One of the most devastating dates in Finn’s and my life together was 20 May 1977, the day the hunting ban in Kenya took effect. Our lives were truly peachy: We had a successful safari business, Finn’s reputation as a knowledgeable and dependable professional hunter was rising, we had bookings and inquiries for several years down the road. We had recently built a small house that could easily be expanded for our growing family, and our three children were healthy and happy. I employed three trusted Africans for my flourishing little farm enterprise with two milk cows, four hundred layers, and vegetables for sale. Finn and I had survived ten years of marriage and were more certain now than when we got married that our partnership would last. Life was sweet, and though I distinctly remember recalling the old Norwegian maxim, still I could not keep from rejoicing over our good fortune.

On that fateful morning, we were visiting friends and were discussing the prospect of going buffalo hunting. Our host had left the house early to get the morning paper and returned almost at a trot while we were at the breakfast table, waving the disastrous news in our faces. Enormous headlines greeted the day:

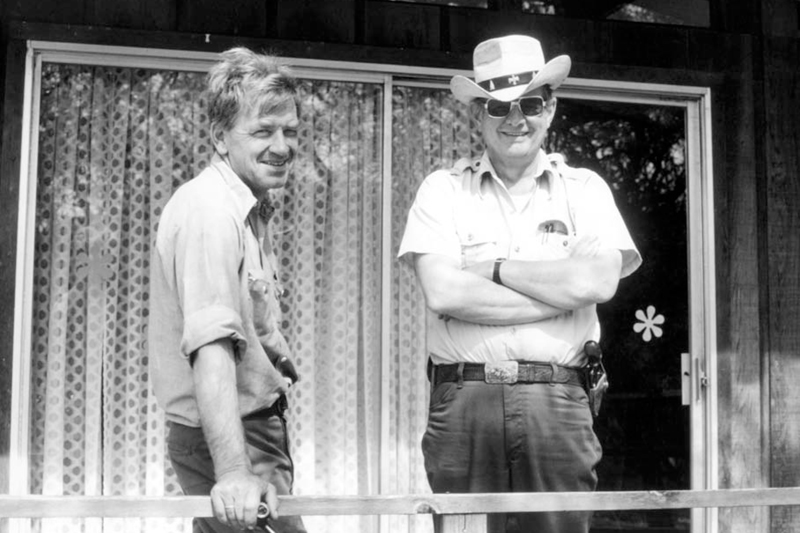

Finn with John Wootters, 1981.

HUNTING BANNED. DIRECTIVE TO SAVE WILDLIFE.

There was an ominous hush as Finn clutched the paper with an incredulous look on his face. My instant reaction was that the whole statement had to be a joke, but, watching his face turn ashen, I felt as if an ice-cold hand had got hold of my heart and started to squeeze. I felt nauseated as Finn stepped out onto the porch and turned his back on the world and us. This was a time for him to be alone; I knew not to disturb him, and I was sure that whatever he decided would be the best and wisest for us and our family. After what seemed an eternity, he came back in and announced loudly and resolutely: “That’s it. We are leaving!”

We had four safaris booked for as many months, deposits paid, clients anxiously waiting to come. Safaris that were already out in the bush had to pack up their camp and return to Nairobi; any trophies collected on May 19 or 20 were confiscated by the game scouts sent out into the bush to bring the devastating news to the hunters and their clients. (Few outfits carried radiotelephones in those days.) Clients arriving at the airport to begin a hunt had to take the return flight back home. A copy of a letter to one of our clients sums up the situation. Finn wrote:

I have held off writing to you in hope that the powers-to-be would come to their senses and lift the incredible hunting ban. The East African Professional Hunters’ Association has done everything it could to have the ban lifted, or at least to get an extension so that we could do the safaris for which we have confirmed bookings, but without success. The minister, Mr. Oguto, has made up his mind and does not intend to be influenced by the facts.*

All the game outside the national parks and reserves will now cease to have any economic value by bringing in money from concessions and hunting fees; it will become just a darned nuisance competing with domestic livestock for grazing. As a zebra is reputed to eat as much as four cows, the landowners and pastoralists will demand, with reason, that this competition be eliminated. Furthermore, the antipoaching teams that the professional hunters maintained in most of their hunting concessions will be disbanded; the poachers will now have it even easier.

The main outlet for the poachers’ booty is the vast array of curio shops in Nairobi, crammed with carved ivory, stuffed lion of both sexes and all sizes down to little cubs, zebra-skin handbags, dik-dik horn charms, piles upon piles of skins of all sorts, anything from Thomson gazelle to eland. There is no indication that anything is going to be done about them; on the contrary, the minister was reported in the local paper as saying: “The government would review this area from time to time to ensure the curio dealers would not experience any difficulties.” It is known that several VIPs own shares in these curio shops, so you can see what we are up against.

*Everyone in the hunting society knew that animals taken on license represented 1 to 2 percent of any given population and that hunting fees contributed a major source of the funding for antipoaching activities. We also knew that top government officials made millions from the sale of illegal ivory and rhino horn (the most notorious was known as the Ivory Queen). Legal hunting parties in the field made it more difficult for the poachers to carry out their nefarious ventures.

Old Bar-O Ranch house in Llano, Texas, where we welcomed our hunters.

I am convinced that the hunting ban means the end of virtually all game outside of the parks and reserves within a couple of years. I do not intend to stay and watch it happen. So, unless you wanted to come on a purely photographic tour, I guess your safari is off. We will send your deposit back as soon as possible, but there is a certain amount of red tape and it could take a little while. . . .

The hunting ban had far-reaching effects, and not only for the wildlife. Obviously, the nation would lose a substantial amount of valuable foreign exchange because each hunter spent large sums of dollars every day for the privilege of hunting. At the time of the ban roughly one hundred professional hunters were operating either part-or full-time. A conservative estimate of the number of employees per hunter would be about ten, not only safari crews but office personnel as well. Each of these people, mostly African, whose multi-generation families easily included ten members, most likely depended on the safari worker’s income to survive. There were hundreds of mechanics, tent makers, taxidermist workers, grocery stores, gun stores, hotels, and clothing outfitters that provided supplies and services; all those people either lost their jobs outright or had their business drastically reduced. A newspaper reported: “Zimmerman, the city’s largest taxidermy shop, is forced to close, leaving 188 Kenyans without a job.” Pretty disastrous for well-trained people with specialized skills in a country that had a 90 percent unemployment rate. An equally telling newspaper article, dated August ’77, announced the dissolving of the East African Professional Hunters’ Association, which had been the pioneer force in conservation and the wildlife industry. That was a time of mourning for all its brave and decent and highly regarded members.

So now what were we to do? Finn had always said that if we were to leave Kenya he would leave Africa; in his opinion, going anywhere else in Africa would be like going from the frying pan into the fire. It was obvious that places like South Africa and then Rhodesia could not hold out forever. Ever since his school days Finn had admired and been convinced of the truth and ideals of the American Constitution and the Bill of Rights. He had already visited the States on several occasions to meet prospective clients, and liked the way of life. We could have stayed in Kenya conducting photographic safaris, but they did not interest Finn in the long run. He could not imagine staying in Africa if he could not hunt or even be allowed to own a firearm to protect his family. The very next day after the hunting ban, Finn crated up all his guns and sent them to a trusted friend in Houston, Texas. It was a very emotional trip into town; Finn was disarming himself and hated it, but he could envision the next move by the highly unpredictable African government: the confiscation of all firearms. To him, that would have been an even worse fate.

There was anger and frustration all around, but no one could do anything about it. Most of all, there was sadness for an era and a way of life that had come to an end. Finn described his heartfelt emotions so eloquently in a letter written a few days after the announcement of the ban: “It is hard to realize that I will never again walk across the plains covered with zebra and wildebeest, see impala flashing red-gold through the bush, have my heart leap into my throat as buffalo suddenly crash in the quiet forest, or stand looking up in awe at a bull elephant—never again hear the hyena’s crazy chuckle or the lion grunting in the night. These things have been a very large part of my life for close to thirty years; I wish I could weep—tears would be a relief.”

Now came the real challenge: how to get into the States legally. Finn wrote to everyone he knew in this country, mostly former clients, and was eventually offered a job with an exotic hunting outfit in the Hill Country of Texas. A thick file contains all the documents and letters that crossed back and forth between Kenya and the U.S., but it only whispers about all the anxious waiting, disappointments, insecurity, and heartbreak for us all during the eighteen months it took to enter legally.

We arrived toward the end of 1978, and Finn started work for a boss half his age whose concept of running a hunting business was very different from Finn’s. Finn disliked the way the animals were killed; there could be no fair chase on one hundred-acre pastures. The outfitter had hunting rights on larger ranches as well; Finn occasionally conducted hunts in rugged granite hills where exotic game ran free on thousands of acres; it was true hunting that required time and skill to be successful. The clients he guided there were delighted with the quality of the hunts, but for the outfitter it was financial disaster; he charged per animal and was happiest when three or four trophies were collected in one morning. When Finn suggested starting “fair-chase hunting” for exotics, the response was that if you could not guarantee kills, nobody would come hunting. Finn finally told the young man that he wanted to leave and pursue hunting the only way he knew how and could ethically accept. The response was positive; his boss must have realized that we would be no threat or competition to him; we would be catering to a totally different clientele. Finn wrote to the owners of the two large ranches where he had previously hunted, proposing to meet and discuss the possibilities of managing the exotic hunting there. The result was that we moved into a very large, ramshackle, abandoned ranch house to start anew. It was a little frightening to be building a business from scratch—Finn was almost fifty, we had three young children, and I had no marketable skills. At least the gods would not notice us as much under our new circumstances!

Finn with Dr. Ted Forrest and a nice axis buck taken on the Bar-O Ranch, September 1994.

The Bar-O Ranch was located in the middle of the Texas Hill Country—pasture land intercepted by dramatic granite formations. Sandy Creek—a dry riverbed most of the year—ran through it. It looked inviting for both elephant and buffalo; leopard would easily have felt at home in the rocky outcrops. Aoudad and mouflon sheep had been stocked in the 1940s and axis deer a bit later; they had, in fact, been there for more generations than most settlers and were for all practical purposes as indigenous as the local white-tailed deer, and they roamed on thousands of acres with no game-proof fences. We instantly fell in love with the whole area and started getting the old house into shape, hoping to attract hunting clients. Our good friend, the late Dunlop Farren, who more than anyone else had helped us through the hurdles of immigration, again came to our rescue. He suggested we invite well-known writers to come hunt with us; in return they would produce stories that hopefully recommended our fledgling outfit. It is ironic that in later years, when Finn himself had become a respected writer, he accepted similar invitations in return for stories, and these hunts became the basis for many of his magazine articles.

Dr. LeRoy Trnavsky with nice Sika deer.

A succession of writers responded, though some a little hesitantly— hunting exotics at the time did not enjoy a very favorable reputation. But soon our guests found that exotic hunting, done right, was indeed challenging. John Wootters successfully field-tested a new Winchester Model 94 .375 big bore on the mostly nocturnal sika deer. The late Gary Sitton, then editor of Petersen’s Hunting, declared he had heard “too many tales of unseemly practices bordering on execution,” but aoudad proved him wrong over and over; there was nothing easy about them, and not until the fourth and last day of hard hunting did he connect. Ken Grisham, outdoor writer for a Houston paper, brought to our ranch a famous baseball pitcher with the idea of writing a story about the sports star going hunting in his spare time. The pitcher was a fairly new bow hunter who had previously hunted only from stands; stalking on hands and knees within twenty or thirty yards was, in Finn’s words, “VERY sporting.” Craig Boddington, also testing a firearm, a .257 Weatherby Magnum, worked hard for several days before bagging a very pretty mouflon ram.

What I remember the most about all these hunts were the many wonderful evenings we had with our guests around the dinner table after long days of strenuous hunting. I served food made from scratch, usually game meat taken on the ranch; the house smelled of freshly baked pies and breads as the men returned tired and hungry. From childhood I had been accustomed to setting tables with sterling and linen and candles; it was only natural to continue doing so. We were entertaining successful professionals who were astonished to find a civilized table in the wilds of Texas. Even though the old-fashioned, worn-down house was not luxurious in any way, tradition, intelligence, and culture graced that dining room. Maybe it was the candlelight or the wine served in family crystal that set the mood, but the conversations and discussions that floated around the table created bonds of friendship with the very people who were supposed to be critiquing and evaluating whether we were any good at doing safaris in Texas so they could produce a story worth writing. Everyone in the room was relaxed and content; Finn’s and my eyes would meet and reflect satisfaction with the results of our hard work done right. When we stood by the front gate and waved farewell to our various guests, we two felt a growing confidence that we had made the right decision by venturing out on our own. We knew we could entertain clients in the old house; there would be ample opportunities for challenging hunting. We were eager to get started.