SIX

BE THE PEOPLE WITH A PLAN

During the 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan, no children died in any of the schools outside the tsunami zone. Tragically, however, multiple parents died trying to get to their perfectly safe children. Most of us feel a strong need to be gathered with our loved ones during perilous times, and having a solid reunification plan will help avoid risking needless injury or worse.

A Cascadia earthquake will make prompt reunification with loved ones difficult or impossible. But unlike a war zone, as communications return and help from the outside surges in after a mega-earthquake, eventual reunification of most survivors will be straightforward. The problem will be the waiting.

There will be no warning with a Cascadia earthquake and little or no ability to communicate with distant household members. Predetermined actions are critical; if your plan hasn’t been made before the earthquake hits, it will be too late afterward to coordinate how best to meet up with each other.

CREATING YOUR REUNIFICATION PLAN

As you make your plan, be sure to emphasize that everyone’s first job is to stay safe. The plan should offer a framework to help make finding each other easier, but a key part is every family member keeping themselves safe until the meeting can happen. Consider the following questions as you put together a plan for your family.

WHERE WILL WE MEET UP AFTER THE EARTHQUAKE

You should decide on a primary location, a secondary location nearby if the first one doesn’t work, and a third backup location outside of your neighborhood. Household members should discuss the challenges of reunification and the best meeting places given work, school, and care locations.

If home isn’t an option for your primary location, choose a place within a short distance. If you choose a park or open space, pick an easily identified landmark there to gather around. It may not be easy to find your loved ones in open spaces crowded with other people.

If your home or nearby meeting place can’t be used because of fire, landslides, or other dangers, where will you meet up outside your neighborhood? Try to pick a place that everyone can get to without going over bridges or overpasses, since there will be no way of knowing in advance whether a location might be dangerous or impossible to get to.

Some cities have predetermined sites to serve as communication hubs to help residents get information and access to help; check with your city or county emergency management agency to see if they have any allocated sites. Consider coordinating your chosen meeting places with these locations. Be aware that these sites are generally not set up to help with water, food, or serious medical needs.

Once your meeting places are chosen, help household members memorize them by visiting the locations every few months.

WHO SHOULD WE CONTACT WITH OUR STATUS AND LOCATION?

Ideally, a single contact person should be someone who lives out of state, or at the minimum someone outside of what is likely to be the severe shake zone (as defined on this page). Make sure your chosen out-of-area contact knows their role as point person for communication.

Immediately after the earthquake, it is possible there will be no cell service, but a text is more likely to get through than a call, and an out-of-area text is more likely to work than a local one. Household members should text the contact person immediately with their status and location, as briefly as possible: “OK, home” or “OK, work.” There is no guarantee an out-of-area contact will be reachable or able to tell you how your loved ones are.

WHO WILL BE RESPONSIBLE FOR PICKING UP CHILDREN OR OTHER FAMILY MEMBERS?

If necessary, establish an emergency caregiver for children or family members residing in assisted living or other care settings. If you know someone within walking distance of your kids’ school or care facility, see if that person might be willing to take your kids to their home in an emergency.

Remember, with power off and evacuation likely, it will not be possible for school personnel to check computer records for who is authorized to pick up your children. Make sure each child knows who their emergency caregiver is and will vouch for them. Supply your emergency caregiver with a picture of each child, along with a signed note authorizing the caregiver to take your children. These steps may help reassure school personnel that it is appropriate to release your children to the emergency caregiver.

If you have older children and think walking home might be a good option for them, find out from school personnel what would be required to make sure they are released after the earthquake. Don’t forget to give older children a go-bag to store at school for getting home.

WHAT IS THE EMERGENCY PLAN FOR SCHOOL, WORKPLACE, OR CARE FACILITY?

Find out what the disaster plan is at your child’s school, your workplace, or anywhere else a loved one spends a significant amount of time. Then figure out how that facility’s plan will interact with your family’s plan.

Most facilities have “all hazards” plans, intended to cover any disaster. Unfortunately, the catastrophic nature of a Cascadia earthquake is beyond the scope of many of these plans. Use the questions below to help you determine whether a disaster plan is adequate for a Cascadia event:

What is the plan to provide water? Food?

How will sanitation be dealt with?

Is there a plan to shelter away from the building? Where would people evacuate to if necessary? (This is especially important in the case of schools or care facilities.)

Is the building expected to remain safe while everyone evacuates? Is it expected to be usable after an earthquake?

Personnel at schools, health-care centers, and other critical facilities are generally mandated by law to remain with those they are responsible for after a disaster. You don’t have to worry about your child or other vulnerable loved one being abandoned, but you do need to worry about the level of preparation their school or care center has achieved. Despite legal mandates, if an employee hasn’t prepared their own household for a disaster, you can understand how difficult it might be for them to accept staying at a care facility or school for several days while their own loved ones might need help.

PLAN B—ADDRESSING INADEQUATE PLANS AT SCHOOLS, WORKPLACES, OR CARE FACILITIES

If you are discouraged by how poorly prepared your child’s school, your workplace, or a vulnerable family member’s care center is to deal with a Cascadia earthquake, please keep in mind that they barely have resources to deal with the common emergencies that occur. Getting ready for a catastrophic event involves investments of time, space, and money that are already allocated to other needs. Long term, see if you can join with others at the school, workplace, or care center to spearhead a better plan, but in the short term, make sure that your family does its best to be prepared and educated.

PUTTING YOUR PLAN INTO PLACE

Once you’ve put together your answers to the questions in the preceding section, you can move on to broader elements of preparing your family and planning for a safe, smooth reunification.

KNOW THE PLAN

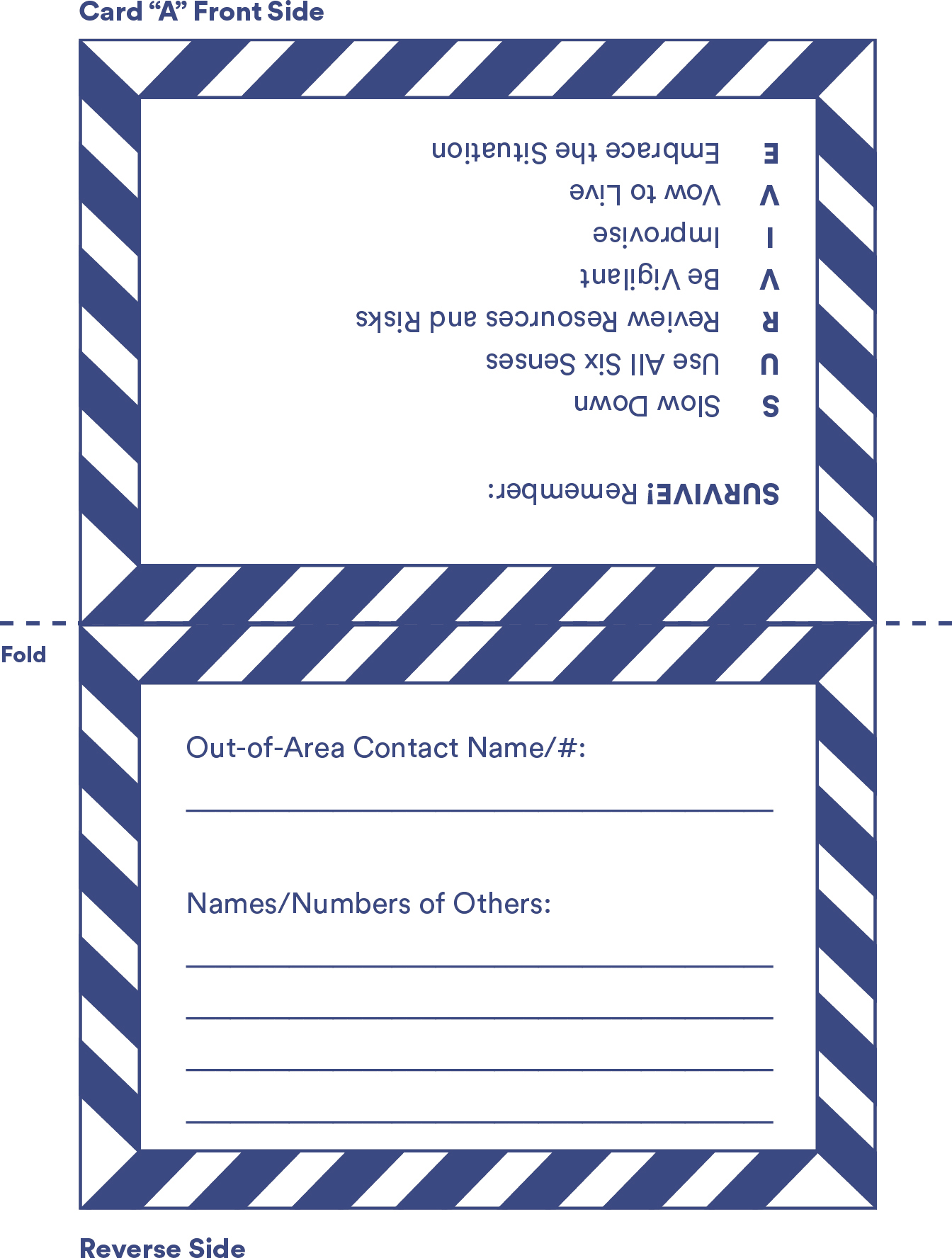

Make sure that everyone has the essential elements of the plan with them at all times. You can use the template in this chapter to create wallet-sized cards and laminate or encase them in clear adhesive contact paper to make them more durable. These cards provide the most critical information for implementing your household plan and staying safe.

For children, more than one set of cards may make sense—a set in their backpack, another in their purse or wallet, and a third sewn into a pocket in their coat. For small children, make sure their caregivers know the household plan and have copies of the cards.

Practice the plan regularly to make sure you are all confident you can follow it in an emergency. Then don’t forget to update the plan when workplace, school, or care facility locations change or household circumstances require revisions.

MATCH EXPECTATIONS FOR REUNIRCATION WITH POST-EARTHQUAKE CONDITIONS

We take for granted the means to instantly know what we want to know, to quickly travel where we want to go. After a mega-earthquake, our expectations need to shift back in time: remember, people used to walk for hours to find out how a neighbor was faring. Our twenty-first-century notions of how long things should take will be dangerous, increasing our sense of urgency to reunite with our loved ones no matter what.

Acknowledge how hard it will be to wait to be together again. Explain to your children why it will take much longer than usual for parents to pick them up, and stress that delays don’t mean the parent is hurt. Reassure children that they will be cared for until they can be picked up. Explain that there could be unexpected things that make following the family’s plan difficult.

Assuming that you’re home from evening to morning most days, remember that the chances are almost 50 percent that you’ll be home with your children when a mega-earthquake comes. However, it is possible that you could be separated from your young children when you or they are somewhere besides school or work: at a movie, at the mall, on a hike, or at a sporting event. In these cases, there may not be an easily identified adult caregiver who will take responsibility for your children’s care and safety.

COMFORT TACTICS

Discuss what will help each person manage the anxiety of being apart. Here are a few things that can help people calm down:

Have family pictures in emergency kits for comfort.

Suggest writing letters to loved ones until you can see them, telling them about your post-earthquake experiences and feelings.

Agree to have a certain time of the day where you will all think of each other; being “virtually” together can provide a feeling of connection.

Teach children breathing exercises to help calm them—and you!

Your reunification planning for a Cascadia event should assume no cell or internet communication, impassable bridges and roads, and limited or no access to first responders. Downed power lines, fires, fallen debris, and aftershocks will make traveling on foot difficult and dangerous. You might get a text through. You might be able to drive to some locations. But if you plan on having twenty-first-century tools and find yourself in a nineteenth-century world, nothing in your plan will work. Assume the worst, and hope for the best.

But assuming the worst doesn’t mean the dramatic movie images of roaming gangs of desperate people out to steal whatever you have with you: other survivors will overwhelmingly be a source of support, not danger.

KIDS LEFT ALONE

Gavin de Becker, an internationally respected security consultant, has extensively studied how to keep people safe. He recommends that parents tell their children to find “a woman who looks like a grandma” and ask for help if they are lost or in trouble. Statistically, an older woman is least likely to be a threat to a child and most likely to assume responsibility for their care.

Does this mean you should instruct your children not to accept help from other strangers after an earthquake? No. The odds are overwhelming that most adults who offer help are unlikely to harm your child. But if your children know to look for a woman who appears old enough to be a grandmother, at least your children have a plan for what to do to get help if they’re alone after a mega-earthquake. This can be reassuring—to you as well as to them.

FOLLOW THESE SIMPLE RULES: SURVIVE

No matter how good your reunification plan is, it won’t work exactly as you expect it to. A favorite quote in emergency management circles is from Mike Tyson: “Everybody has a plan until they get hit.” A set of simple rules to remember during a period of separation after a mega-earthquake can go a long way to helping everyone in your household be confident that the others know what to do when there are challenges not covered in your plan.

SURVIVE guidelines—outlined in more depth in Chapter Fifteen (this page)—provide a simple framework to help your loved ones pay attention to the right things after the earthquake, so everyone stays safe and well until you can be reunited. Here is a brief rundown:

S is for Slow Down: Everything will take longer. Speed can be dangerous. Go slow.

U is for Use All Six Senses: What do you see, hear, smell, taste, feel? Do you have any hunches or “gut feelings” about what to do or not do? Use all six senses to stay aware of your situation and avoid danger.

R is for Review Resources and Risks: What do you have? What do you need? What risks are you facing? How can you solve the challenges you face? Assess for the group of people you’re with.

V is for Be Vigilant: If you’re safe, stay safe. Be cautious about what you do, who you believe, and the information you base your decisions on.

I is for Improvise: Make do with what you have by improvising ways to use things to cover what you need.

V is for Vow to Live: Decide you are going to do whatever it takes to survive. Hoping you’ll make it through is not the same as vowing to.

E is for Embrace the Situation: After the earthquake, you and your loved ones need to make the best of wherever you are and whoever you’re with until there is a safe way to reach each other.

REUNIFICATION PLAN CARDS TO CARRY

Photocopy this template or create a similar business card– or wallet-sized plan for your family members.

REUNIFICATION CHECKLIST

□ Meeting location

□ Backup location nearby

□ Out-of-neighborhood location

□ Out-of-area communication contact

□ Message for out-of-area contact

□ Backup caregivers to pick up children or other family members

□ Comfort tactics

□ Plan to practice and rehearse

□ Plan cards for pockets, purses, backpacks, and wallets