Fundamentals of Form: Posture, Breath, and Integration

‘Externally, practise the form,’ advises an ancient Chinese maxim. ‘Internally, practise the meaning.’ Correct form is very important in chi-gung, and without it the inner meaning of the practice is easily lost. How the various parts of the body are held in balance in a particular posture, how the limbs and torso move through the forms, and how the movements are integrated with the various phases of breath – all of these factors exert decisive influence on the magnitude, balance, transformation and flow of energies in the channels. Different breathing techniques mobilize and modulate breath and energy in different ways, and every practitioner of chi-gung should have a variety of basic breathing methods in his or her repertoire for appropriate applications in practice. The various forms of posture and breath used in chi-gung are external factors: they establish the fundamental framework for practice. Energy and mind are internal factors: they reflect the main meaning and represent the major goals of practice. In order to understand the inner meanings of the outer forms of practice and accomplish such internal goals as balancing energy, activating internal alchemy, expanding awareness, and harmonizing the mind, one must first establish a stable external foundation in practice by carefully cleaving to the basic rules of form, such as proper posture, correct breathing and the integration of breath with body and energy.

In the following pages we shall review the basic points of attention in the four fundamental body postures used for moving and still styles of chi-gung practice and discuss seven different methods of breathing that may be used in chi-gung, each with its own distinctive effects on respiration, circulation and energy. Then we’ll take a look at how breath is synchronized with body in moving forms of chi-gung, and how to breathe in harmony with the movement of energy in still forms.

Four Postures for Chi-Gung Practice

Regarding the importance of proper posture in chi-gung, an old Chinese medical text states, ‘When posture is not proper, energy is not smooth; when energy is not smooth, mind is not stable’. Even the smallest point of posture can make a big difference in how smoothly energy circulates through the body during practice, and this in turn determines how energy influences the mind. Conversely, if the mind is not stably balanced prior to practice, energy will not flow smoothly through the system, and this in turn will throw posture off balance. For most people, it’s much easier to start by balancing the body rather than the mind, and therefore establishing proper posture in the body is usually the first step in practice. In chi-gung, posture is the fundamental foundation upon which a strong, stable practice is built.

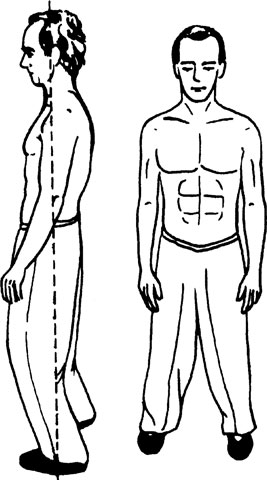

Fig. 11 The ‘Horse’ stance, the most important posture for practising chi-gung; note the alignment of the crown, solar plexus and abdomen with the centre of the feet

Standing (Fig. 11)

Moving forms of chi-gung are usually practised in the traditional ‘Horse’ stance, which may also be used for still standing meditation. This is a very stable posture for standing practice, with a firm but flexible foundation in the legs, a low centre of balance below the navel that makes it easy to adjust and maintain directional equilibrium, and a ‘tower of power’ rising through the spine to link the energy of Earth in the sacrum with the energy of Heaven in the head. So important is the Horse stance in Chinese martial arts and chi-gung, that traditional masters often required new students to spend the first year practising nothing but ‘Standing Pylon’ in the Horse posture, until they could stand stably in that position for up to two or three hours.

The primary guideline for proper posture in the Horse stance is to keep the top of the head in perfect alignment with the lower elixir field in the abdomen, the Yin Confluence at the perineum, and the midpoint between the feet of an imaginary line drawn between the two Bubbling Spring points on the soles. Viewing the Horse stance from the side, there should be a straight line from the crown of the head down through the centre of the body to the lower elixir field and on down through the perineum to the point directly between the two Bubbling Spring points in the feet. The Horse posture facilitates free flow of energy between ‘Heaven’ in the head and ‘Earth’ in the sacrum and feet, opens energy circulation in the Governing Channel that runs up along the spine from sacrum to cerebrum, and draws energy into circulation in all eight channels of the Macrocosmic Orbit. Major points of attention for maintaining proper posture in the Horse are as follows:

• Feet should be exactly shoulder-width apart and perfectly parallel. Some teachers suggest that women, due to the structure of the pelvis, place their feel splayed out at a 45-degree angle. Female practitioners should try both ways of placing the feet and adopt the one which feels more comfortable in practice. Body weight should rest evenly on both feet, with the centre of gravity on the front pads, of ‘balls’, of the feet, not back on the heels. The toes should be spread for better balance and slightly flexed to ‘grip’ the ground, but without tensing the feet.

• Knees are kept unlocked, relaxed and slightly bent, so that the main burden of body weight rests on the thighs, not on the hips and lower back. Keeping the knees unlocked also facilitates free flow of blood and energy between calves and thighs.

• Hips should be relaxed and loose, allowing the weight of the upper body to be supported primarily by the thighs. Tuck the pelvis slightly forward to pull in the buttocks and straighten out the curvature in the lower spine. Keeping the buttocks tucked in makes it much easier to keep the spine aligned and maintain proper balance in the Horse. It also encourages energy to rise up the spinal channels from sacrum to cerebrum.

• Abdomen should also be relaxed, so that the diaphragm may expand freely down into the abdominal cavity on inhalation. However, an excessively flaccid abdominal wall is a disadvantage, because it expands too far on inhalation thereby negating the therapeutic benefits of compression, and is difficult to draw inward for the abdominal lock and the final phase of exhalation. Strengthening your ‘abs’ is therefore a good way to enhance your chi-gung practice.

• Chest should be neither tense nor jutted out in front during chi-gung practice. If the spine is straight and the shoulders are relaxed, the chest will naturally fall into proper position. By slightly rolling the shoulders forward (without stooping the upper spine), the entire thorax will relax, thereby facilitating deep abdominal breathing.

• Spine must be held erect throughout a session of chi-gung practice. Imagine a string attached to the crown of the head, pulling the entire spinal column upward. Proper spinal posture is facilitated by keeping the back of the neck straight and the chin pulled slightly down, but without tilting the head forward, and by keeping the buttocks tucked in. This stretches the spine and keeps the vertebrae well aligned.

• Shoulders should be loose and completely relaxed, so that the arms hang naturally down by the sides, the chest remains relaxed, and the muscles of the neck and upper back are free of tension.

• Elbows should be kept unlocked to allow the arms to dangle loosely by the sides and the energy to flow freely up and down the arm channels. The hollows of the elbows face inward towards the ribs, so that the palms are facing toward the back.

• Hands must remain completely relaxed during practice, with fingers slightly curled and palms hollowed. ‘The hands are the flags of energy,’ states an old chi-gung adage, which means that they respond to even the slightest ‘wind’ of chi. The lao-gung points in the centre of the palms are the most powerful transmitters of energy in the entire body, but any tension in the hands tend to impede their conductivity.

• Head is kept straight, as though suspended from a string. Except when required as part of a particular exercise, do not tilt the head forward or backward or from side to side during practice.

• Neck remains aligned with the spine and stretched upward by tucking the chin slightly downward, without tilting the head forward. Try to keep the muscles of the neck and throat relaxed. Any tension in the neck tends to block the free flow of energy into the head.

• Eyes are usually kept half-open during moving chi-gung exercises to help maintain balance and directional equilibrium. Eyelids and eyeballs should remain completely relaxed, and the eyes should not be focused on any particular object. Just keep the eyes in an unfocused gaze, aimed either straight ahead or at the ground a yard or so (a meter or two) in front. In still meditation, the eyes may be kept closed to turn attention inward and facilitate visualization of internal energy.

• Mouth should also be relaxed, without any tension in the jaw or lips. Except when doing mouth exhalation, keep the lips closed, but not so tightly that it causes tension in the face, and keep the upper and lower teeth touching, but without clenching the jaw.

• Tongue should be kept relaxed in the mouth, with the tip pressed lightly against the palate behind the upper teeth. This forms a ‘bridge’ for energy to pass from the Governing Channel into the Conception Channel in the Microcosmic Orbit circulation. Raising the tongue to the palate also helps stimulate secretion of highly beneficial saliva from the salivary ducts below the tongue. This should be swallowed as it pools in the bottom of the mouth. You may also curl the tongue back so that the tip is pressed against the soft palate at the top of the throat; this provides a stronger stimulation to salivary secretions.

Sitting

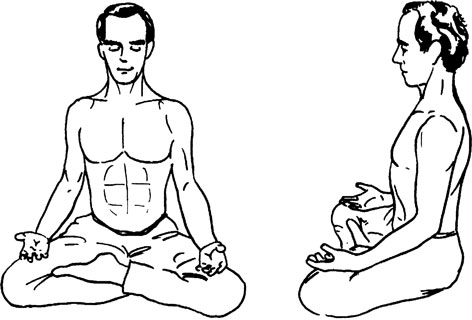

There are two basic sitting postures for chi-gung: sitting cross-legged on the floor, sofa or platform (Fig. 12); and sitting on the edge of a low stool or chair with the feet flat on the floor (Fig. 13). These postures are used mainly for still meditation practice, although some moving exercises, such as the Eight Pieces of Brocade set, may also be performed in sitting posture.

The cross-legged position is known as the ‘Lotus Posture’, and it has two variations – half lotus and full lotus. If your legs and knees are limber enough to hold the full lotus, that’s the most stable and balanced sitting posture for still meditation, but it’s best to learn this position from a qualified yoga or chi-gung teacher. The posture illustrated and described here is the half lotus, which is much easier for most people to hold without experiencing discomfort.

Fig. 12 Sitting posture: legs crossed in the ‘Half Lotus’ position

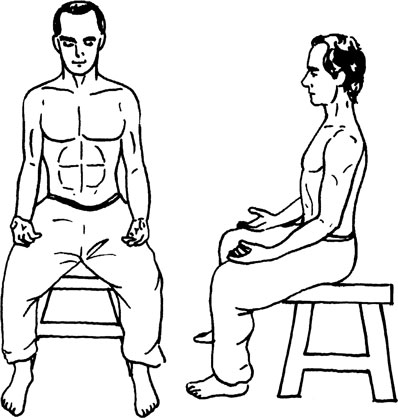

Fig. 13 Sitting posture: sitting erect on a low stool

If you’re sitting on the floor, it’s best to use a mat or carpet. If you use a bed or sofa, be sure that the sitting surface is very firm. Place a small, hard cushion, folded towel or telephone book under the buttocks to elevate and tilt the pelvis. This makes it easier to hold the lotus posture for prolonged periods without straining the lower back, hips and thighs, or getting numb in the legs. Cross one leg so that the foot is tucked comfortably under the opposite thigh. Then cross the other leg and place that foot on top of the opposite thigh, as shown in the illustration. The soles of both beet should be facing upward. Sit with spine held erect, but don’t let the chest stick out in front. Shoulders should be completely relaxed and slightly rounded, neck straight, chin drawn slightly inward, head held as though suspended from a string.

There are many different ways of placing the hands during still meditation. Hand postures, known in Sanskrit as mudra, are regarded as very important aspects of meditation practice in Hindu and Buddhist tradition, as well as in Taoist practice. As ‘flags of energy’ that are particularly sensitive to chi, the hands, and how they are held during practice, have a decisive influence on how energy moves in, out and through the human system. For purposes of cultivating energy in chi-gung, especially exchanging energy with external sources in nature and the cosmos, the most effective and beneficial way to place the hands is to rest the back of the hands comfortably on top of the thighs, so that the palms face the sky, with fingers relaxed and slightly curled, upper arms perpendicular to the ground, and elbows bent at an angle of a little over 90 degrees.

The hands should not be touching each other. In this position, the energy gates on the palms are most receptive to the inflow of fresh energy from external sources, while also allowing stagnant energy to be expelled from the system. Placing the hands palms-down on the thighs shuts them off from external energy sources, while cupping the hands together with fingers and thumbs touching or intertwined causes internal energy to circulate within the system, rather than facilitating exchange between internal and external energies. Each of these methods has its place and function in various styles of meditation, but for purposes of cultivating internal energy by harnessing the power of external sources, the best way is to place the hands separately palms-up on the thighs.

The other sitting posture is a more traditionally Chinese method. It’s much easier to hold for people with stiff or weak knees, poor circulation in the legs, or lower back problems, and it tends to extend energy circulation from the two main channels of the Microcosmic Orbit into all eight channels of the Macrocosmic Orbit.

Use a low stool or chair that allows a 90-degree angle between thigh and calf when sitting. A firm cushion, pad, or folded towel may be placed on the stool for comfort, but the sitting surface should not be too soft. Sit on the edge of the stool so that the buttocks are flush against the surface but the genitals are over the side. Feet should be flat on the ground or floor, parallel and shoulder-width apart. Spine, neck, and head are kept straight and properly aligned, as in the lotus posture, with hands placed apart and palms up on top of the thighs.

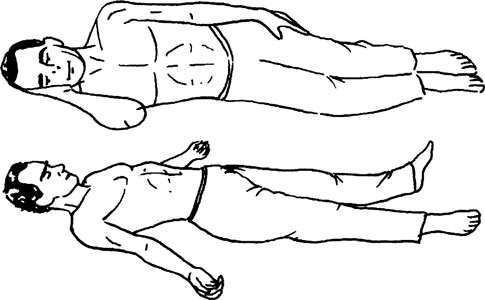

Lying (Fig. 14)

The lying posture is generally used only when it’s not possible to practise in the standing or sitting positions due to illness, old age or physical handicaps. Since the body is lying parallel to the ground in this position, there is virtually no potential gradient between sacrum and head, which reduces the polarity and flow of energy through the system. It also puts uneven pressure on the spine, which further impedes free flow of energy. Nevertheless, practising chi-gung in this posture still has its benefits: the movement of the diaphragm massages the internal organs; the basic vital functions of circulation, digestion, nerves and endocrine response are stimulated and balanced; the pH of blood and other bodily fluids is normalized; tissues are oxygenated, and so forth. It is only the higher stages of internal alchemy that are somewhat impeded by practising in the reclining position, but the basic physiological benefits remain much the same.

Fig. 14 Reclining posture: lying on the right side; lying on the back in the ‘Corpse’ posture

There are two basic lying positions – side and back. In both positions, it’s very important to lie on a firm, flat surface. Most beds are too soft for practising chi-gung in the reclining position. This can usually be corrected by placing a board under the mattress; otherwise, lie on a mat or carpet on the floor. When lying on the side, it’s customary to lie on the right side: not only does this take pressure off the heart, it also facilitates inhalation through the left nostril, which, due to its upper position, tends to remain more open when lying on the right side. The left nostril is associated with the right hemisphere of the brain, which houses the intuitive faculties and is therefore more conducive to working with internal energy and spirit. The head should lie on a small, firm pillow, with the right hand placed between head and pillow and the left arm stretched comfortably down along the left side. Legs should be slightly bent, with the knees and ankles more or less together, although the upper leg may be brought forward a bit so that the knee and ankle are resting on the surface just in front of the other leg. The main point of attention here is to keep the spine as straight as possible.

The other lying posture involves reclining flat on the back, legs apart, arms slightly spread out to the sides with palms facing upward. The head should be resting on a small firm cushion, with a rolled towel under the neck for added support to prevent unbalanced pressure on the upper spine. Known in hatha yoga as ‘The Corpse’, this position is very effective for totally relaxing the whole body. Since it requires absolutely no flexion of muscles or tendons to hold this position, it can be used to dissolve all traces of tension throughout the body. The best way to achieve total relaxation of the body in this position is to start by focusing attention down at the toes and slowly work your way up from feet to legs, legs to hips and abdomen, up the torso and down the arms to the fingers, then up the neck to the head and face, consciously and very deliberately relaxing each and every muscle, tendon and joint along the way.

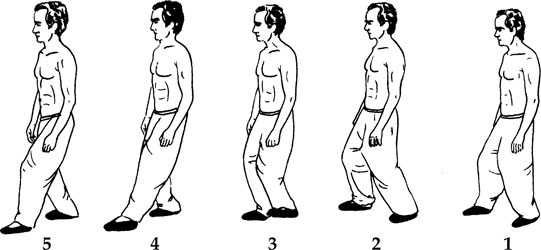

Walking (Fig. 15)

Walking forms of chi-gung include all of the ‘internal’ styles of Chinese martial arts, such as Tai Chi Chuan, Hsing Yi and Pa Kua. A distinctive feature of these traditional ‘soft-style’ Chinese martial arts is that they may be practised purely as chi-gung sets to cultivate energy and awareness, or to cultivate martial power and fighting skill for combat. When practised as chi-gung to cultivate energy, the manoeuvres are performed very slowly and deliberately in a predetermined sequential order; when used as martial arts in combat or competition, the movements are executed with lightning speed, and each step arises in specific response to the opponent’s movements.

Fig. 15 Walking posture: the ‘Tai Chi Walk’

Walking may also be practised as a form of chi-gung in itself, without the elaborately choreographed steps, arm and leg extensions, and twists and turns of the torso that characterize Tai Chi Chuan, Pa Kua and other internal forms of martial arts. The best time and place to practise walking chi-gung is early in the morning, just after dawn, barefoot on an open lawn, while the grass is still damp with dew. This is an excellent way to energize the whole system with the pure potent Yang energy that prevails at this time of day. The dew serves as a highly efficient conductor of this energy, transmitting it from the ground into the leg channels via the Bubbling Spring point on the soles.

When practising walking chi-gung, you should do it in conjunction with deep diaphragmic breathing and a clear, calm, meditative state of mind. Other than a dew-damp lawn at dawn, this form of practice, which is also known as ‘Tai Chi Walking’ and the ‘Lotus Step’, may be done on the beach, in a driveway, or indoors on the floor. If it’s not possible to do it barefoot, the next best way is either in cotton or wool socks, or in soft shoes with soles made of leather or cotton. Socks of synthetic fibre and shoes with soles of rubber or plastic are poor conductors of energy and tend to block the upflow of terrestrial energy and the downflow of celestial energy.

In chi-gung walking, the knees are kept bent throughout each step, not straightened out on forward extension as in ordinary walking, and the soles of the feet are kept parallel and very close to the ground at all times, not lifted at different angles. This means that each forward step is taken by lifting the entire rear foot off the ground at once (not the heel first), bringing the foot forward while keeping the sole parallel and close to the ground, then setting the whole foot evenly and flatly down on the ground in front (not the heel down first, then the toes). The body thus moves forward slowly and smoothly, in a straight line, without the head bobbing up and down and the torso swaying from side to side on each step as in ordinary walking. The spine is held erect and aligned with the neck, the head is kept straight, the arms hang down relaxed by the sides, and the pelvis is tilted slightly forward to keep the buttocks tucked in and the lower spine straight. Taoist texts refer to this gait as ‘walking like the wind’.

This style of chi-gung draws terrestrial energy from the earth into the system, circulates it in the Macrocosmic Orbit, and stores it in the reservoirs of the Eight Extraordinary Channels. It builds strong ankles, knees and thighs, improves balance and coordination in the body, and cultivates concentration, clarity and focused attention in the mind. While moving chi-gung exercises practised in the standing posture involve movements of the arms, head and torso, with the legs kept stationary, walking forms move the feet and legs, while keeping the upper body still. These two styles of ‘moving meditation’ therefore complement one another very well and may both be practised in the same session.

Seven Ways of Breathing in Chi-Gung

Deep diaphragmic breathing is the core technique in all styles of chi-gung, moving as well as still. Without breath control, chi-gung is nothing more than ‘going through the motions’ of moving or holding the body in a particular manner. Breath control is the key to energy control, and breath is the bridge that allows mind to take command of body and regulate all of its vital functions.

Like physical exercise, there are many different ways to exercise the breath, each with its own particular benefits and purposes in practice, so it’s a good idea for practitioners of chi-gung to familiarize themselves with a variety of basic breathing exercises. Though each of the seven breathing methods introduced below has its own unique features and applications, all of them utilize the diaphragm to drive the breath, thereby massaging and stimulating the internal organs and glands, and all of them boost circulation of blood and energy, enhance immune response, regulate the nervous and endocrine systems, improve digestion, elimination, and other vital functions, and balance the polarity of energies throughout the system.

Incremental Bellows Breath

This is a version of the classic Bellows Breath used in pranayama to clear the lungs, oxygenate the blood and stimulate the brain. It may be used as a preliminary exercise to balance the breath and stimulate the circulation of blood and energy in preparation for chi-gung practice, or by itself for a quick lift any time of day.

Method: Take three sharp, short inhalations in quick succession through the nose, one on top of the other, followed by three sharp, short exhalations, and continue in this manner without pause for one or two minutes only. Exhalation may be done through the nose or by blowing the breath out through pursed lips as though blowing out a candle. Nose exhalation has a stronger clarifying effect on the brain, while mouth exhalation works more on clearing the blood and body.

Benefits: Bellows breathing has manifold benefits, especially as a preparatory exercise for chi-gung. It expels stale air and residual toxins that have accumulated in the deeper recesses of the lungs and opens up the bronchial and nasal passages. It increases the amount of carbon dioxide eliminated from the blood through the lungs, while increasing the amount of oxygen assimilated from the air, thereby purifying the bloodstream and stimulating metabolism. The swift, strong contractions strengthen the diaphragm and tone the abdominal muscles, which in turn improves the body’s capacity to perform deep abdominal breathing. They also provide an invigorating vibrational massage to the internal organs and glands.

Bellows breathing is particularly beneficial to the brain. It greatly enhances microcirculation throughout the brain, delivering abundant supplies of oxygen and glucose to the neurons to support vital cerebral functions. The vigorous exhalations give rise to rhythmic waves of enhanced circulatory drive that extend throughout the bloodstream, travelling up the carotid arteries to the brain where, in addition to irrigating the whole brain with oxygen, they also cause a gentle rhythmic expansion and contraction of the brain itself. This cerebral massage stimulates secretions of essential neurotransmitters and balances vital cerebral functions of the brain. The resulting mental clarity is one of the primary benefits of this breathing exercise, particularly in preparation for still meditation practice.

Natural Abdominal Breathing

This is the main breathing method used in all forms of chi-gung practice. It’s also the way you should learn to breathe throughout the day. It’s the way babies and animals naturally breathe, and the way our respiratory systems were designed to function. Breathing this way during ordinary daily activity is one of the most effective steps you can take to protect your health and prolong your life.

Method: First of all, the entire breathing apparatus should be completely relaxed, especially the diaphragm and ribcage, with shoulders loose and slightly rounded. Inhale slowly and smoothly through the nostrils, letting the air travel in a steady stream down to the bottom of the lungs, and press the diaphragm downward. This is turn will cause the abdominal wall to expand outward. If you wish to apply the abdominal lock, do so at the end of inhalation, but do not draw the abdominal wall in too far: pulling it in about 1 inch (2 to 3cm) is more than enough to achieve beneficial compression in the abdominal cavity. When ready to exhale, relax the abdomen and release the breath in a long, slow, even stream, letting the diaphragm rise up again and the abdominal wall contract inward toward the spine. Before commencing the next inhalation, pause briefly to permit the diaphragm and abdominal wall to relax and fall back into their natural position, then start the next cycle.

Benefits: Abdominal breathing provides a stimulating massage to all of the organs and glands in the abdominal cavity, particularly the all-important adrenal glands, which sit on top of the kidneys directly below the diaphragm. It turns the diaphragm into a ‘second heart’ to assist in the circulation of blood and greatly enhances respiratory efficiency in the lungs. It also catalyses internal alchemy by gathering energy into the ‘cauldron’ of the lower elixir field below the navel, opening the Microcosmic Orbit circuit of energy circulation, and facilitating the transformation of hormone essence from the adrenals and other glands into vital energy.

Reverse Abdominal Breathing

This is a more advanced variation of abdominal breathing that significantly amplifies compression in the abdominal cavity and gives an even stronger boost to the circulatory system. It may be used in all chi-gung exercises, but it requires more focused attention to the breathing process, more careful timing, and more deliberate effort. Therefore, it is more appropriate for moving exercises than for still practice, unless the latter is focused primarily on cultivating energy rather than spiritual work. When practising still sitting for spiritual cultivation, the attention and effort required for this breath tends to distract the mind.

Method: Inhale the same way as in natural abdominal breathing, except as the diaphragm descends into the abdominal cavity, rather than letting the abdominal wall expand outward, you should deliberately contract it inward towards the spine, thereby further increasing the compression within the abdomen. The deliberate contraction of the abdomen during inhalation automatically applies the abdominal lock. To further enhance the compression provided by this breath, the anal lock should also be used on completion of inhalation. On exhalation, as the diaphragm rises, simply relax the abdominal wall and let it expand outward again.

Benefits: This breath greatly enhances abdominal compression. It also increases the relative difference in pressures between the abdominal and chest cavities, thereby providing a very strong pumping effect on circulation. It stimulates secretion of gastric juices in the stomach and duodenum, squeezes stale blood from the liver, and enhances peristalsis in the bowels. It’s also a good way to cultivate volitional control over the breathing process.

Chi Compression Breath

This breath may be used to increase the assimilation of atmospheric chi from air, pack it into the lower abdomen for storage, and guide it to particular organs and tissues for healing purposes. It also gives a strong boost to blood circulation and increases the beneficial effects of internal organ massage by enhancing and maintaining abdominal compression.

Method: This breath is basically the same as natural abdominal breathing, except that each of the four stages of breath control is lengthened and the three locks are applied more strongly and held a bit longer to enhance and sustain compression. It helps to visualize energy as radiant light streaming down into the lower elixir field on inhalation, condensing there during compression, then entering the spinal channel through the coccyx and rising up to the head on exhalation. If you wish to send energy to heal an ailing organ or injured tissue, visualize the energy as bright light streaming into the target organ or tissue on inhalation, condensing there on compression, and flowing out as dark fog or smoke on exhalation, thereby clearing away the negative energy responsible for the injury or illness.

Inhalation and exhalation should be a bit longer and slower than in other breathing exercises, and the compression stage may be held for up to 10 seconds, although if you hold it for that long, it’s better to use a sitting posture as a precaution against dizziness that may occur as a result of enhanced cerebral circulation. Prior to applying the neck lock, swallow hard, even if you have no saliva to swallow, because this manoeuvre helps pack energy down into the lower elixir field, thereby enhancing abdominal compression and boosting energy into the Microcosmic Orbit circulation.

Benefits: This breath increases the beneficial compression of the abdominal organs and glands, while also enhancing the assimilation and storage of energy from external sources in the lower elixir field and major channels. It stimulates the central nervous system and activates the immune responses of the parasympathetic branch. It may be effectively used to guide healing energy to cure or strengthen specific organs and tissues, or to pack extra energy into the reservoirs of the Eight Extraordinary Channels, especially when practising at special times and places that offer the practitioner a ‘bumper crop’ of potent energy for harvest and storage.

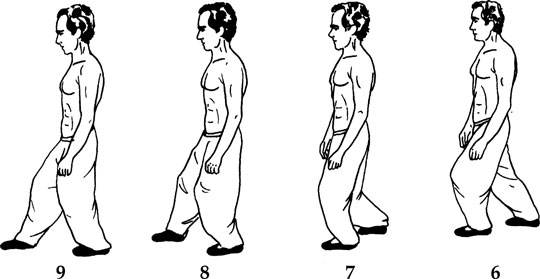

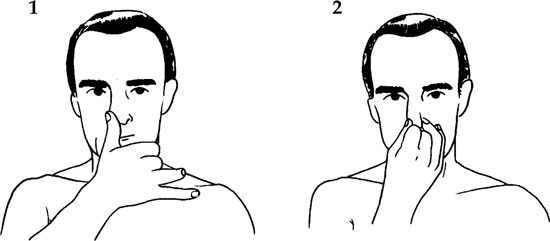

Alternate Nostril Breathing (Fig. 16)

This exercise is designed to alternate air flow between right and left nostrils, thereby balancing breath, and also to balance energy flow and the cerebral functions of the right and left hemispheres of the brain. It may be practised as a chi-gung exercise in itself, in the standing or sitting postures, or as a preliminary exercise to balance the breath in preparation for moving or still chi-gung.

Fig. 16 The alternate nostril breath:

1. Right thumb blocks right nostril, inhale through left nostril

2. Both nostrils blocked, brief compression

3. Right thumb opens right nostril, while ring and little fingers block left nostril; exhale through right nostril

4. Both nostrils blocked, brief intermission

Method: Inhale deeply through both nostrils, then use the thumb of the right hand to seal shut the right nostril, and exhale slowly and evenly through the left nostril. Keeping the right nostril sealed with the right thumb, take a long, slow inhalation through the left nostril. When lungs are full, fold the index and middle fingers of the right hand against the palm, and use the fourth (ring) finger to seal shut the left nostril. Keep both nostrils sealed briefly while you compress the breath and apply the three locks, then release the thumb from the right nostril (keeping the left nostril sealed), and exhale through it. Keeping left nostril sealed, inhale through the open right nostril, then seal it with the thumb, compress and lock, then open the left nostril (keeping right nostril sealed), and exhale. Repeat until you have done six breaths on each side. Men should start by exhaling through the left nostril and finish by exhaling through the right, as above. Women should start with an exhalation through the right nostril and finish by exhaling through the left side, also using the right hand to control the nostrils.

Benefits: Alternate nostril breathing balances the flow of air between right and left nostrils and helps open up the sinus cavities. Since air flow is twice as strong when inhaling through one nostril, alternate nostril breathing exposes the nasal membranes to more concentrated levels of chi than in ordinary breathing, permitting more energy to be absorbed from the air. This breath also balances the flow of energy between the right and left sides of the body, and balances the cerebral functions governed by the right and left hemispheres of the brain. The latter effect makes it a particularly good exercise to practise during still sitting meditation, for it helps awaken the dormant intuitive faculties of the right lobe and integrate them with the rational faculties of the left.

Vibratory Breathing

There are many different healing sounds and sacred syllables used for vibratory breathing in Tibetan Buddhist, Taoist and Hindu traditions, but generally it’s best to learn these directly from a qualified master, because many of them must be adapted specifically to the individual’s energy system. A few, however, may be practised without special adaptations.

Vibratory breathing involves the sounding of various syllables to create waves of vibration in the throat. These vibrations spread through the tissues up to the brain and down into the deepest recesses of the lungs and heart, stimulating the fluids, massaging the cells, and opening various energy centres. These vibrations are also transformed into beneficial electromagnetic pulses by virtue of the piezoelectric properties of crystalline molecular structures in bones, connective tissue and electrolytes.

Method: Take a deep inhalation through the nose, compress the breath down into the lower abdomen, then open the mouth and throat and sound the syllable loud and clear with a long, even, controlled exhalation, continuing until the lungs are completely empty. Never interrupt the sounding of a healing or sacred syllable, and don’t stop until exhalation is complete.

One of the most effective syllables for vibratory breathing is ‘ah’, which is the sound associated with the throat chakra. Use whatever pitch feels most natural to your voice and keep the throat wide open while you’re sounding it. Focus not only on the sound, but also on feeling the vibrations spreading out from your vocal cords, penetrating deeply into the surrounding tissues.

In Tibetan tradition, which emphasizes the importance of sound as a manifestation of energy, mantra are used extensively in meditation, both for spiritual as well as healing purposes. There are three sacred ‘seed syllables’ which Tibetan meditation masters teach that encompass the sounds and effects of all other mantra, and indeed of all sound in the universe. These three syllables are ‘Om’, ‘Ah’ and ‘Hum’ (pronounced ‘hoom’). The first is associated with the upper elixir field energy centre in the head. When toning it, lips should be well rounded for the initial ‘ooh’ sound, which should take up about three-quarters of the exhalation, followed by the ‘mmm’ with lips sealed. ‘Ah’ governs the throat chakra and all spiritual faculties related to that energy centre. ‘Hum’ is related to the heart chakra and human consciousness. In the latter tone, the initial ‘hu’ (pronounced ‘hooo’) takes about one-quarter of the exhalation, followed by a long vibratory ‘mmm’.

When used for energy work in vibratory breathing, the effects of these syllables are universal and therefore independent of any religious connotations they might have in various cultural traditions, so anyone may practise them for health without worrying about creating conflicts with personal religious beliefs.

Benefits: Vibratory breathing stimulates the entire breathing apparatus with a vibratory ‘massage’, and this effect extends up into the brain as well. It loosens any residual mucus accumulated in the recesses of the lungs and stimulates microcirculation in the brain. The major energy centres along the spine (chakras) respond to vibratory breathing by opening and transmitting energy. The vibrations are also transformed into electromagnetic pulses by crystalline structures in various tissues, and these pulses have therapeutic healing effects on the internal organs and glands.

Energy Gate Breathing

In this mode of breathing, attention is switched over from the flow of air in and out of the lungs to the flow of energy in and out of various energy gates, using intent, visualization and feeling to activate, amplify and sustain the stream of energy through the gates. This is especially beneficial when practising at times and places where the ambient energy of nature and the cosmos is particularly pure and potent (see “The most potent atmospheric chi . . .”).

Method: Start by breathing in the natural abdominal mode, focusing attention on the various points of breath control until body, breath and mind are balanced and harmoniously tuned. Then shift your awareness over to one or more of the major energy gates, such as the ‘Medicine Palace’ on the crown of the head, the ‘Yin Confluence’ at the perineum, the ‘Labour Palace’ points on the palms, or the ‘Bubbling Spring’ gates on the soles of the feet. First visualize the gate itself, then visualize energy streaming in through the gate on inhalation and focus attention on the feeling at the gate as energy flows through it. Use intent and visualization to guide the energy into the lower elixir field for storage, or else to heal a specific organ, tonify tissues, or stimulate vital functions. On exhalation, you may wish to guide energy back out through the same or a different gate, or draw negative energy out of a specific organ or tissue, or simply condense and pack the energy collected on inhalation into the ‘Sea of Energy’ in the lower elixir field

Benefits: This breathing method collects energy from external sources and guides it into the lower elixir field for storage, or into ailing organs and injured tissues for healing. It may also be used to expel excess Fire energy from the system and to drive stagnant and toxic energy out of specific organs and meridians. Therefore it’s a good way to recharge your energy ‘batteries’ and refill your energy reservoirs. It’s also an effective practice for cultivating volitional command over energy, developing the faculties of visualization and intent, and learning how to see and feel energy moving in, out and through the body.

Integration of Body and Breath

Establishing unison between the slow rhythmic movements of the body and the deep cyclic waves of the breath is a central point of attention in moving forms of chi-gung. In all such exercises, the breath always sets the pace, and the body follows. As breath grows deeper and longer, movements of the body become slower and more deliberate, with the mind orchestrating the two aspects of the practice.

In most exercises, unless specifically stipulated otherwise, upward and inward movements of the arms and head are done on the inhalation stage of breath. Downward and outward movements are performed during the exhalation stage. For example, if an exercise calls for the arms to be raised up above the head, that movement is made on inhalation, while the arms return down to the starting position on exhalation. Similarly, arms are drawn inward towards the body on inhalation and extended away from the body on exhalation.

If compression and the three locks are applied upon completion of inhalation, this stage of breath occurs halfway through the body movement, when the arms are fully extended above or drawn in close to the torso. The brief intermission of breath between the end of exhalation and the beginning of the next inhalation happens when the arms and hands have completed one full cycle of movement and returned to the starting position.

In order to use movements of the body to guide energy mobilized by breath, it’s essential to maintain rhythmic synchronicity of body and breath throughout the exercise, and this requires focused attention and presence of mind. As soon as the mind drifts off in thought or gets distracted by external phenomena, body and breath lose their synchronicity, and energy scatters.

Integration of Energy and Breath

In still forms of chi-gung practice, in which the body remains motionless, breath must be synchronized in unison with the movement of energy rather than the movement of the body. This is accomplished by utilizing the mental faculties of visualization and intent and by developing a feel for the movement of energy in the body, such as in the ‘Energy Gate Breathing’ discussed above.

On inhalation, you should visualize and try to feel energy rising upward through various channels in the system, or flowing into the body through the gates. On exhalation, energy moves downward through the system, or outward through the gates. It’s important to distinguish between energy moving within the system and energy moving in and out of the system through various gates. For example, energy ascends up the Governing Channel along the spine from sacrum to brain on inhalation, and down the Conception Channel in front, from brain to lower abdomen, on exhalation. However, when drawing energy in through the gate on the crown of the head on inhalation, it travels downward to the lower abdomen, and when driving it back out the same gate on exhalation, it travels upward to the head. In other words, when moving energy within the system, inhalation coincides with upward movement, and when moving energy in and out of the system, inhalation coincides with in-flow and exhalation with outflow, regardless of whether the energy moves upward or downward from the gate once it’s inside the system.

If compression and the three locks are applied in breathing, visualize and try to feel energy collect and condense wherever the mind had guided it upon completion of inhalation. During the brief intermission between exhalation and the next inhalation, energy stops moving.

These are only general guidelines for still practice. Whereas in moving exercises the unison of body and breath is crucial to success in mobilizing and guiding energy through the body, in still practice the unison of energy and breath is not as essential, because energy responds primarily to the mind in sitting practice. Therefore, if the practitioner has developed strong faculties of visualization and intent, he or she can easily mobilize and guide energy entirely with the mind, without using the breath for assistance. In this case, breathing remains on ‘automatic pilot’ in the background, while the mind works directly with energy. For beginners, however, integrating breath and energy so that they move together facilitates energy work in the practice of still meditation.