CHAPTER 3

Patterns of Grief and Intuitive Grief

☐ Theoretical Basis for Patterns of Grief

This chapter begins with a discussion of the theoretical basis for the patterns. Then, initial differences between the instrumental and intuitive styles or patterns of grief are discussed. Also examined are less differentiated or blended patterns. Stipulations regarding the patterns are stated, and then the chapter examines the intuitive pattern of grief in detail.

In this section a theoretical basis is constructed that accounts for many of the differences between instrumental and intuitive grief. The chapter begins by revisiting grief as a concept and identifying a model of emotion. Then, a comprehensive model of grief is constructed and the chapter goes on to elaborate on the function and development of the structures and mechanisms responsible for differences among grievers. Finally, the agents that shape the development and influence the individual’s unique pattern of responding to loss are introduced.

Grief as Emotional Energy

In Chapter 2, grief was defined as a multifaceted and individual response to loss. In short, grief is energy—an emotional reaction to loss. In order to lay a theoretical foundation for patterns of grief, it becomes necessary to revisit and expand on the definition.

Although the word “emotion” is often used as a synonym for the word “feelings,” the modern definition of the term “emotion” is far more comprehensive, with “feelings” being just one component of emotion. For this book’s purposes, emotions are defined as biologically based, adaptive reactions involving changes in the physical, affective, cognitive, spiritual, and behavioral systems in response to perceived environmental events of significance to the individual.

Grief, then, is emotion, an instinctual attempt to make internal and external adjustments to an unwanted change in one’s world—the death of someone significant to the griever. Grief involves both inner experience and outward expression. Building the foundation begins by looking more closely at emotion and adopting the general model of emotions proposed by Gross and Munoz (1995).

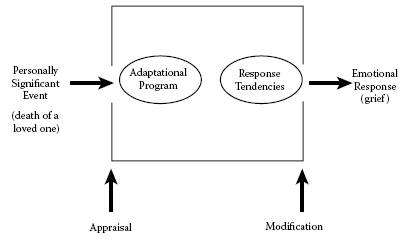

The model in Figure 3.1 incorporates both a component as well as a process view of emotions. The component perspective of emotion includes a biologically based adaptation program for survival and a conglomeration of response programs (spanning all of the adaptive systems or modalities) referred to as response tendencies. These various programs represent learned predispositions, which usually operate at a subconscious level and enhance the chances of an individual’s survival by being readily available and quickly activated.

Whereas the adaptational program is genetically and biologically determined, response tendencies result from previous and ongoing interactions with the environment. From birth, the person’s response tendencies are molded by powerful, often imperceptible influences. As will be shown, two of the most influential forces are the individual’s culture (both societal and familial and their influence on gender-role development) and personality.

FIGURE 3.1 General model of emotion (Gross & Munoz, 1995).

Two processes are active in emotions. Appraisal is the cognitivebased, semiconscious process, which activates the adaptational program and continues to shape the eventual response. The second process is modification, a conscious effort on the part of the individual to determine the final emotional outcome.

Whether one is more intuitive than instrumental in his or her grief depends on a variety of factors related to emotion. Thus far, as seen in Figure 3.1, emotion has been reduced to its fundamentals—two components and two processes. How do these various components interact to produce either the instrumental or intuitive style of grief? Using the aforementioned model as a starting point, a comprehensive model of grief will be offered.

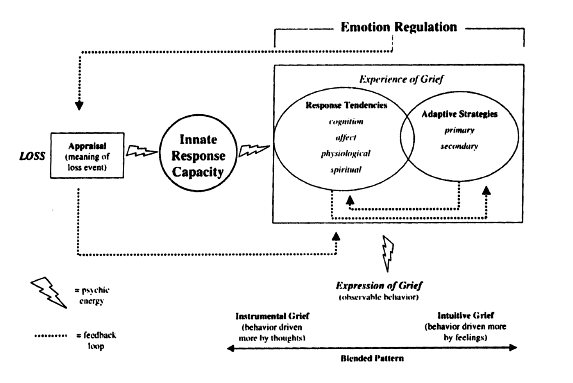

Figure 3.2 presents a comprehensive model for understanding instrumental and intuitive grief. In the first phase of the model, an individual appraises an event involving a loss as negative.1 The appraisal process is essentially the way the individual gives meaning to an event, in this case, a loss. This initiates a preprogrammed biological response—the arousal of psychic energy—that varies in capacity from person to person.

FIGURE 3.2 Comprehensive model of grief.

This instinctual arousal of energy triggers changes in various adaptive systems—affective, cognitive, physical, and spiritual—that constitute the individual’s response tendency. Response tendencies are predispositions, operating subconsciously and allowing people to quickly and efficiently react to environmental threats, challenges, and opportunities. These predispositions are shaped by the powerful forces of culture and personality and are mediated by the process of emotion regulation.

Emotion regulation mediates the griever’s adaptive strategies as well as response tendencies. Adaptive strategies represent the conscious, effortful aspect of emotion regulation and are the griever’s attempt to manage both his internal experience of grief and the outer expression of that grief. Whether one is more cognitive or affective in his or her response tendencies and his adaptive strategies determine whether his or her is more instrumental or intuitive in nature.

The proposed comprehensive model is not closed. In other words, actions that happen later in the process can produce a change in the appraisal process, resulting in different arousal levels of psychic energy, different response tendencies, different adaptive strategies, different expressions of grief, and so on. In particular, the griever’s choice of adaptive strategies produces changes in behavior that may influence the griever’s immediate internal or external environment, thus generating a new appraisal of an altered situation. In fact, it is the constant alteration of the griever’s perception of his or her plight that continually generates energy, eventually resulting in an accommodation to the loss. Additionally, previous adaptive strategies modify response tendencies that in turn, influence the selection of current and future adaptive strategies.

Gross and Munoz (see above) identified modification as a process involving a conscious effort on the part of the individual to shape his final emotional response. While this is useful, we have chosen the term “emotion regulation.” Emotion regulation is emerging as an important concept in the general study of human behavior and has both automatic (subconscious) and conscious properties. Furthermore, it plays a pivotal role in mediating between shaping agents and response tendencies.

Thus, patterns of grief are a function of two variables: the individual’s innate response capacity and emotion regulation, with emotion regulation governing response tendencies and adaptive strategies and, through feedback generated by the chosen adaptive strategy, indirectly influencing the appraisal process.

☐ The Appraisal Process

The appraisal process is the starting point since it involves cognition, and cognition is crucial to differentiating instrumental from intuitive grief. What is cognition? What roles does cognition play in how people live and what people do?

Definition of Cognition

“Cognition,” as used here, refers to conscious and subconscious mental activities that involve thinking, remembering, evaluating, and planning.

Cognitive activity is vital to the instrumental griever; it connects his or her feelings and motivations and serves to differentiate the instrumental style of grieving from the intuitive grief pattern. Understanding the dominant role played by cognition in grief is tantamount to understanding the instrumental grief response. Searching to further clarify the relationship of cognition to emotions and thus grief (instrumental grief in particular) leads directly to the field of stress research and the role of cognitive appraisals in emotions.

Cognitive-Appraisal Stress Theory

Relating stress to grief is not a revolutionary idea; grief is the response to the stress of bereavement. One theory that has dominated the field of stress research since the 1980s is the cognitive-appraisal stress theory.

In the cognitive-appraisal theory, stress is seen as a threat to the individual’s well-being and as a source of undesired emotions (Lazarus, 1966, 1991; Lazarus, Averill, & Opton, 1970; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The quality and intensity of emotion result from ongoing attempts to understand and make judgments regarding what the individual’s senses are reporting about what is happening between that person and the environment. Negative emotions arise when the individual perceives a phenomenon as a danger or a threat to his or her sense of well-being or, in some cases, to his or her very survival!

The person then considers options for responding to these dangers or threats and eventually chooses a course of action. This chain of cognitive events is cognitive appraisal. The stress inherent in the death of a significant other triggers the cognitive appraisal process, which is fundamental to the instrumental grief response. Cognitive appraisal processes determine how, and how well, the individual copes.

Just as cognition is both necessary and sufficient for emotions, emotions affect cognition (Lazarus, 1991). After the initial appraisal is made and emotion arises, secondary and subsequent appraisals can engender thoughts that are emotional. In a “kindling” sense, once aroused, emotions produce feedback that affects subsequent thoughts, which produce additional emotions, which produce new feedback, and so on. Apparently, the personal meaning one gives to an event (and its attendant responses) is a function of both thinking and feeling. Whether one is more tuned in to his or her thoughts or his or her feelings determines whether he is an instrumental or conventional griever. Now return to the model of grief and explore the nature and development of response tendencies.

Response Tendencies

As noted in Figure 3.2, the individual’s response tendency is initiated by a chain of events beginning with the appraisal of an event as a loss, which, in turn, triggers the arousal of psychic energy (adaptational program). This energy is channeled into the various inner modalities constituting the response system—cognitive, physiological, affective, and spiritual. Chapter 2 explored how these modalities found expression in various reactions to loss. One should not infer that there is a one-to-one correspondence between the inner experience of these modalities and their final expression seen in observable behavior. As will be shown, much of the outward expression of grief depends on the griever’s chosen adaptive strategies.

While response tendencies represent habitual responses to loss, they remain somewhat plastic, that is, modifiable. How do response tendencies develop? Can individuals actively shape their response tendencies by modifying and modulating their experience as well as their expression of grief? Is there any one process, beyond the appraisal process, that is responsible for both the experience as well as the final expressions of grief? These questions are best answered by examining the concept of “emotion regulation” (Izard, 1991; Thompson, 1994; Gross & Munoz, 1995).

Emotion Regulation

Even the earliest studies of the link between thoughts and feelings demonstrated that some people could modulate their emotions at will. In one instance, prior to seeing a movie of people suffering personal injury while working with machine tools, subjects were instructed to either be more involved with events on the screen or to detach themselves from the emotional impact of the scenes (Koriat, Melkman, Averill, & Lazarus, 1977). The results indicated that participants could either, by using cognitive strategies, become more emotionally enmeshed in an event or achieve emotional detachment. Stated differently, these subjects managed their emotions by regulating them.

Additional researchers concluded that infants (Rothbart, 1991) and children (Saarni, 1989) developed strategies and skills for managing their emotional experiences and expressions. This process of modifying emotions is called emotion regulation. Thompson (1994, p. 27) formally defined emotional regulation as, “the extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features, to accomplish one’s goals.” What is not clear is exactly what is being regulated.2 Is emotion regulation primarily concerned with the management of expressions of emotion or the underlying arousal processes leading to those expressions—or both?

The answer to this question lies at the heart of understanding grief as well as implementing effective interventions with grievers.3 At present, researchers do not know whether emotion regulation is primarily the management of expressions of emotion or the underlying arousal processes leading to those expressions.

☐ Functional Aspects of Emotion Regulation: Adaptive Strategies

It is important to understand that emotion regulation is a process that helps people achieve their goals (Campos, Campos, & Barrett, 1989; Fox, 1989). Emotion regulation is not just a way of suppressing emotions, but a vehicle for expressing them as well. The reader should distinguish between emotion control, which implies restraint of emotions, and emotion regulation, which refers to the attunement of emotional experience to everyday events and the achievement of goals (Davis, 1983). Emotion regulation has been defined in terms of how one uses emotions to achieve one’s goals. Other writers have added that it is the individual’s goals that determine the nature, type of, and persistence of emotion regulation (Walden & Smith, 1997).

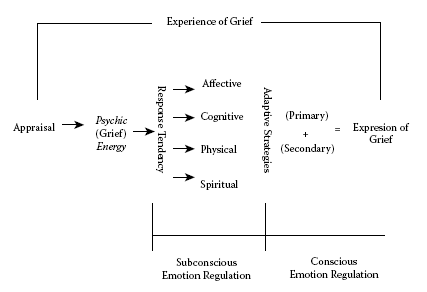

Thus, emotion regulation involves both subconscious and conscious processes that govern the experience and expression of grief. Emotion regulation reflects the individual’s inherent arousal capacities and influences the development of his or her response tendency. Along with the appraisal process, emotion regulation also modifies the griever’s ongoing experience and expression of emotional (or psychic) energy. Ultimately, how the individual adapts to loss is largely a function of how he or she distributes emotional (or psychic) energy. He or she does so by selecting adaptive strategies.

The term “adaptive strategies” describes the conscious regulatory efforts of the individual. How the griever regulates the psychic energy created by his or her loss reflects what objectives are important to him or her at the time. This has important implications for counselors and therapists working with the bereaved, since the efficacy of the regulatory efforts must be evaluated with respect to the griever’s individual pursuits. Furthermore, the professional should keep in mind that these pursuits may change as a function of place, person, or time. These regulatory efforts will be revealed in the adaptive strategies the individual chooses.

Hence, a griever modifies or adjusts the final expression of his or her grief through choosing adaptive strategies. This process acts in concert with the individual’s response tendencies to produce the grief response. Response tendencies represent the subconscious, automatic responses to bereavement and are mediated by the appraisal process and subconscious aspects of emotion regulation. Adaptive strategies are the conscious, effortful acts on the part of the griever to manage his or her experience as well as how he expresses his or her grief. Yet the reader should remember that adaptive strategies, once learned, influence response tendencies (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.3 shows how the processes of emotion regulation, both subconscious and conscious, govern the experience and expression of psychic or grief energy. Emotion regulation operates subconsciously in shaping and modifying response tendencies, while it represents a conscious process in influencing the griever’s choice of adaptive strategies, which in turn influence future subconscious processes.

Primary adaptive strategies are those that represent the griever’s dominant mode of regulating emotional energy, while secondary adaptive strategies may be employed to supplement or temporarily replace primary strategies. Primary adaptive strategies provide important clues to differentiating instrumental from intuitive grievers.

FIGURE 3.3 Emotion regulation of grief.

☐ Adaptive Strategies and Patterns of Grieving

The basic style of the griever is reflected in his or her choice of primary adaptive strategies. Intuitive grievers usually choose primary adaptive strategies that permit an unfettered, uninhibited experience of the affective component of grief. These strategies represent a means to an end. They may also choose secondary strategies that allow them to manage the other modalities of emotional experience—cognitive, physical, and spiritual.

On the other hand, instrumental grievers select primary adaptive strategies that help them distribute cognitive psychic energy into planned activity. They often choose secondary adaptive strategies to manage the intensity and duration of their feelings, cope with physical responses, and deal with spiritual issues such as facing the challenges to their belief systems posed by the death of a loved one.

Thus, individuals play a decisive role in selecting how they experience and express their emotions. Grievers may begin to regulate their responses either before (proactively) or after (reactively)4 the response begins. A proactive regulatory effort might involve the adaptive strategy of avoiding situations that have led to unpleasant emotions in the past or choosing an environment incompatible with the unpleasant emotion. The sought after environment could be physical (choosing to be with friends in order to distract oneself from feelings of loneliness) or mental (engaging in thought control, meditation, positive imagery). Grievers often choose “dosing” methods of mental control. Proactive regulation itself can give rise to new appraisals, different levels of arousal, different response tendencies, and so on. The following case illustrates proactive emotion regulation.

Matt had just turned 27 when his fiancée, Susan, died suddenly after experiencing a lethal allergic reaction to a snake-bite. He sought counseling after receiving an invitation from Susan’s parents to spend her birthday with them. Although Matt had always enjoyed a good relationship with Susan’s parents, he felt anxious and ambivalent about the invitation. From previous experience, Matt had discovered that being with Susan’s family stirred up painful memories. After a recent visit (at her parents’ request), Matt was overwhelmed with feelings of despair and hopelessness. By contrast, “hanging with my single friends” had proven both relaxing and fun for him. After an intense discussion with his minister about his conflicted feelings, he decided to write a letter to his fiancée’s parents, explaining his feelings and asking them to forgive him if he avoided contacting them for the foreseeable future. Susan’s parents responded immediately to Matt’s letter with one of their own. Their letter lay unopened for several days, until Matt chose to risk the feelings he knew that reading the letter would ignite. To his relief, Susan’s parents expressed their own ambivalence about being around Matt and encouraged him to “get on with” his life.

Whereas anticipation of a negative event or response stimulates proactive attempts to avoid painful emotions, reactive emotion regulation begins late in the cycle of emotion response. Reactive regulation means modulating or modifying already existing thoughts and feelings so that the outcome response is altered. Hiding one’s true feelings or maintaining strict control over impulses or behaviors is an example of reactive regulation. The following case illustrates a reactive emotion regulation.

After surviving several years beyond his life expectancy, Margi’s younger brother, Michael, died from complications arising from cystic fibrosis. He was 41 years old. Michael and Margi had been extremely close growing up. After their parents died and following Margi’s divorce, they grew even closer and made sure they spoke with each other almost every day. Margi shared her brother’s last days with him, temporarily closing her busy law practice to remain at his bedside. She was overwhelmed with intense feelings at Michael’s funeral and, as she described it, “I spent about four days in a haze.” Despite her intense grief, Margi knew she needed to return to her legal practice if she wanted to remain competitive in the local economy, which had a surfeit of attorneys. “I knew I needed a plan to get my feelings under control if I was to be able to concentrate at all, so I set up a schedule for grieving: I could only think about Michael for an hour every evening. Believe you me, I spent that hour being miserable!” (Question: “How did you keep your mind away from thoughts of your brother?”) “Oh, I’ve always been able to distract myself from thinking things I didn’t want to. Remember, I had lots of practice during his fight with CF. I just know how to turn my thoughts on and off.”

Of course, as will be discussed in Chapter 5, grievers can choose adaptive strategies that do not lead, ultimately, to a healthy resolution of their loss. Hence, adaptive strategies can subdue (or enhance) the intensity of feelings, strengthen (or defeat) action plans, and retard (or speed) recovery.

In summary, instrumental grief is a response tendency that is driven primarily by thoughts rather than by feelings, while the response tendency of an intuitive griever reflects the preponderance of psychic energy that is experienced as feelings. Both patterns of grief response can be modified or modulated according to environmental demands and individual needs by choosing adaptive strategies and employing them either proactively or reactively. Emotion regulation is at the heart of grieving. The next section will look briefly at the development of emotion regulation and introduce the change agents shaping this development.

☐ Development of Emotion Regulation

How do emotions develop? How does emotion regulation emerge in the developing child? What role does biology play? What is the role of personality in shaping emotion regulation? Is the family a purveyor of emotion regulation? How important are gender differences in emotion regulation?

In exploring the object of emotion regulation, Thompson (1994) concluded that emotion regulation targets the various neurological processes governing emotional arousal. Congenital differences in central nervous system reactivity may represent differences in how and to what infants attend. As the infant develops, his or her attention processes become more complex than the earlier, simple strategies, such as shifting vision from an undesirable stimulus to one more desirable in order to avoid negative feeling states.

Older children use more internal strategies for emotion regulation. For example, a child might discover that thinking about the coming summer vacation becomes an antidote to worrying about tomorrow’s exam. Children also regulate, to an extent, their access to support systems, when they become aroused by a noxious event. They choose whether to seek support and from whom they will seek it. Of course, the way in which parents or others respond to cries for help from the child who experiences unpleasant, painful feelings either reinforces or fails to reward future help-seeking behaviors. As emotion regulation becomes more complex and sophisticated, it is shaped more by environmental factors. Gender role socialization, the family, and cultural influences assume a larger role in determining the development of emotion regulation as they interact with individual biological predispositions and the child’s emerging personality (see Sidebar 3.1).

Sidebar 3.1. Instrumental grief as a mature pattern

Among the many questions that arise about the patterns is, “Isn’t instrumental grief simply the same pattern displayed by young children, that is, isn’t this pattern an example of the griever who hasn’t matured enough or become strong enough to handle difficult feelings for extended periods of time?” The question is a good one, since it is widely accepted that children have a “short sadness span” (Wolfenstein, 1966) and often grieve intermittently.

The answer is “no.” In this case, the questioner may be confusing the experience of grief with the expression of grief. Instrumental grief is a pattern, marked by tempered affect and heightened cognitive activity, not a series of discrete experiences (“now I’ll have feelings, now I won’t, now I will…”), although most grievers sometimes choose to modulate and dose their feelings. Efforts of this sort are mature, sophisticated strategies for dealing with uncomfortable levels of affect and are used by intuitive and blended grievers as well as instrumental grievers.

Actually, this concern about immature responses calls into question interpretations of children’s reactions to loss. Children often act out their internal experiences symbolically through play. Since traditional views of grief tend to overemphasize the importance of affect, these behaviors have been seen as the child’s way to avoid or minimize painful feelings. It is equally likely that these responses are ways that children express physical, cognitive, and even spiritual energy created by their losses. Also, doing things like watching television or random play are interpreted as the child’s attempts to escape uncomfortable feelings. While this may be so, could not a child experience grief without expressing it? And how are we to know if one bereaved child’s minimal responses represent an attempt to avoid feelings or are indicative of that particular child’s smaller capacity for feelings of any type, or of his or her inclination to process the world cognitively rather than affectively? Could this child’s behaviors be part of an overall emerging pattern of responding to loss— an instrumental pattern?

☐ Summary

- Grief is an emotion. Feelings are just one of the adaptational aspects of emotions. The other modalities of adaptation are the cognitive, the spiritual, and the physical.

- A comprehensive model of grief and patterns of grieving includes an initial appraisal, which creates psychic energy. This energy is distributed among various adaptational systems according to the griever’s response tendencies. Response tendencies are subconscious predispositions that are mediated by the process of emotion regulation and shaped by culture and personality.

- The appraisal process initiates the grief response by attaching meaning to the event as a significant personal loss. This is accomplished through cognitive activity. Appraisal is also strongly influenced by the process of emotion regulation.

- The mechanism primarily responsible for shaping and modifying both internal and external aspects of response tendencies is emotion regulation. Emotion regulation also plays a conscious role in determining which adaptive strategies are chosen by the griever and how these strategies are implemented.

Patterns of Grief

This section begins by illustrating the various patterns of grief using the following case example.

It was Friday morning. After briefly discussing an upcoming fishing trip with his youngest son, making dinner plans with his wife, and teasing his teenage daughter about her date that evening, David left for the post office where he planned to mail a check to cover his younger son’s fraternity dues. He never got there. A massive heart attack killed him as he waited at a traffic light. He had just turned 46.

David’s family was shocked by his death, yet they each responded to the crisis in different ways. His eldest son, Josh, showed no emotion until his voice quivered and failed him as he eulogized his father at the funeral on Monday. On Tuesday, he returned to work. He remained impassive, avoiding any discussion of his father and refusing any offers of help and comfort from his girlfriend. Yet, when he was alone, powerful feelings threatened to overwhelm him. Josh dealt with this threatened loss of control by drinking himself to sleep every night. Two weeks later, he received his first DWI. Finally, after an angry outburst at his supervisor, he reluctantly agreed to see a counselor. He never kept his first appointment. Within a year of his father’s death, Josh had withdrawn from everyone, including his girlfriend. He had also developed ulcerative colitis and was well on the road to alcoholism.

David’s 15-year-old daughter, Sarah, was inconsolable. She returned to school several days after the funeral but found it impossible to concentrate. She had trouble sleeping and cried for hours every day. Sarah eventually found comfort in attending a bereavement support group sponsored by a local funeral home. Sarah’s mother urged her to also get professional counseling, following an episode of acute anxiety. After 8 months, she reported feeling much better, although she still experienced painful feelings whenever she thought about her father.

As soon as he heard of his father’s death, Vincent stopped preparing for his final exams and immediately returned home. Although he felt overwhelmed with feelings, he managed to limit his crying to the times he shared with his sister and his mother. Two days after the funeral, Vincent returned to school and successfully completed his exams. He later told a frat brother that he was able to do well on his exams only because he knew his father would have wanted him to “get on with living.” In the months that followed, Vincent was often overwhelmed with painful memories of his father, yet he found he could remain focused on his classes if he shared difficult feelings with his closest friends.

Janice, David’s wife, threw herself into making the necessary arrangements for his funeral. She wept at the funeral on Monday, but by Wednesday she was immersed in settling her late husband’s estate. Although Janice made several inquiries about support services for her daughter and accompanied her to the first bereavement support group meeting, she chose not to return. She found the raw emotionality of the group uncomfortable and unhelpful. She felt restless and channeled her excess energy into her garden, enjoying the time alone to reflect on her years with David. When her friends called to offer their support and companionship, Janice politely declined, stating that she preferred to be alone with her thoughts.

Although Janice felt sad and diminished by David’s untimely death, she was never overwhelmed by the intensity of her feelings. Much of her grieving involved thinking about the issues and the challenges created by David’s death as well as discovering the skills she needed to confront those challenges. Janice confronted (and conquered) everything from an unruly lawnmower to an overzealous insurance agent. The following fall, Janice enrolled at a local college, and 2 years later she was well on the way to completing dual degrees in secondary education and nutrition.

Each of these family members grieved, but their grieving took very different forms. The daughter’s grief, although intense and persistent, eventually subsided. She found comfort in sharing her plight with other grievers who had similar losses. She also benefited from professional counseling. Her response to her father’s death represents the pattern generally thought to be intuitive grief. In many respects, the wife’s response is the most interesting, since it defies classification. She experienced her grief as more rooted in thinking than in feeling, and she focused her energies on solving problems presented by her husband’s death. She preferred reflection and chose not to talk with others about her feelings, finding these self-disclosures uncomfortable and unhelpful. She discovered outlets for her grief that were apparently healthy. In this case, the wife’s grief could be seen as instrumental grief.

Although there were clearly observable differences between the wife’s and daughter’s responses, both had similar outcomes. Conversely, the sons’ public reactions appeared similar, while the outcomes were very different. Josh’s response was seemingly impassive, but it eventually resulted in damage to his relationships, job, and health. His outward stoicism belied his inner anguish and turmoil. This might be seen as the typical “male” response to bereavement. In fact, this son’s reactions represent a maladaptive or dissonant response. (Dissonant responses are explored further in Chapter 5.)

Vincent, too, appeared outwardly unaffected by the death, yet found effective ways to express his grief through sharing feelings with just a select few and channeling his energy into his academic work. Unlike Josh, Vincent chose strategies that did not damage his health or relationships. His reactions represent a more blended pattern of grief.

☐ Patterns of Grief and Adaptive Strategies

Identified so far are two distinct major patterns of grief—intuitive and instrumental. These patterns vary in two general ways: by the griever’s internal experience of his loss and the individual’s outward expressions of that experience. In other words, patterns (or styles) of grief differ according to the direction taken by converted, grief-generated psychic energy, as well as by the external manifestation of that energy. The modalities of internal experience that are most useful in discriminating between the patterns are the cognitive and the affective. The intuitive griever converts more of his or her energy into the affective domain and invests less into the cognitive. For the intuitive griever, grief consists primarily of profoundly painful feelings. These grievers tend to spontaneously express their painful feelings through crying and want to share their inner experiences with others. The instrumental griever, on the other hand, converts most of the instinctual energy generated by bereavement into the cognitive domain rather than the affective. Painful feelings are tempered; for the instrumental griever, grief is more of an intellectual experience. Consequently, instrumental grievers may channel energy into activity. They may also prefer to discuss problems rather than feelings.

Thus, it is the relative degree to which the griever’s thoughts and feelings are affected that accounts for the differences between the patterns. However, what a griever is experiencing can never be directly observed; it only can be inferred by observing how the individual expresses his or her experience. In particular, the griever’s desire for social support, the need to discuss feelings, and the intensity and scope of activities are varying ways of expressing grief and are often important in distinguishing between patterns. These expressions of grief usually (but not always) reflect choices, both past and present, that the griever has made or is making to adapt to losses. These choices are the griever’s adaptive strategies.

Intuitive and instrumental grievers usually choose different primary adaptive strategies. Primary adaptive strategies are the principal ways grievers express their grief and assimilate and adapt to their losses over long periods. These strategies tend to differ according to the pattern of grief. Grievers use additional or secondary adaptive strategies at various times and under specific circumstances. Secondary adaptive strategies are those strategies that grievers employ to facilitate the expression of the subordinate modalities of experience. For example, intuitive grievers choose additional strategies that aid them in accomplishing tasks requiring planning, organization, and activity—all expressions more common to their instrumental counterparts. Conversely, instrumental grievers need to find ways to express their feelings about their losses, and whereas intuitive grievers are quite familiar with strong feelings, instrumental grievers are less so. These secondary adaptive strategies are not as familiar or accessible as primary adaptive strategies, nor are they as critical to the individual’s overall adjustment to the loss.

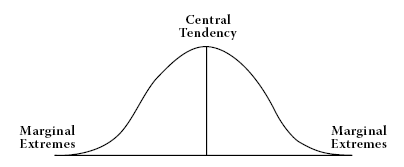

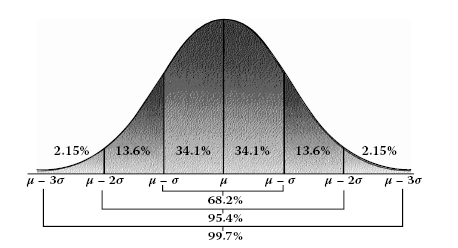

Now that the two patterns have been described, a most important caveat must be stated: Few people display the “ideal” intuitive or instrumental response. Most grievers are a blend of both styles. This can best be seen as an example of patterns fitting the “normal curve” or “normal frequency distribution.” If one were to measure every person’s pattern, assigning a score representing the strength of that particular pattern, those scores would be hypothetically distributed in the shape of the normal curve. This is particularly true if one is measuring either psychological (in this case patterns of grief) or physical characteristics (height and weight). Figure 3.4 illustrates this effect.

As can be seen, the patterns of grief are arranged along a continuum, with the majority of people clustered toward the center and a very few at either extreme. While theoretically there exist those whose pattern is a perfect 50–50 blend of intuitive and instrumental styles, in reality most people lean toward one pole or the other. Therefore it would be correct to state he/she is more intuitive than instrumental and vice versa. This further highlights the contention that there is no one “right” way to grieve. The blended styles or patterns of grief are less likely to be identified with a clearly defined specific primary or secondary adaptive strategy. Blended grievers choose strategies that are more evenly balanced, reflecting the greater symmetry between the cognitive and affective responses of the individual. The overall responses of blended grievers are more likely to correlate with what have been identified as the various phases (Parkes, 1987) or stages (Kavanaugh, 1972) of grief. For instance, early on, the griever may need to subjugate feelings in order to plan and implement funeral or other arrangements. Later, he or she may give full vent to feelings, seeking help and support in sharing. Later still, cognitive-driven action may overshadow the individual’s feelings as the griever finds it necessary to return to work, assume parenting roles, and so forth. This is particularly true of those grievers who have a near perfect blending of both the instrumental or intuitive patterns.

FIGURE 3.4 Normal distribution.

Now that it is understood that most people are either more instrumental or intuitive, we can say that, in reality, there are three primary patterns: intuitive, instrumental, and blended. Figure 3.5 highlights the distribution of styles in terms of “standard deviations” from the center of central tendency. To further discussion of the three styles or patterns of grieving, we will arbitrarily designate that anyone within one standard deviation of the mean (the 50th percentile) can be understood as blended. Those who fall beyond one standard deviation from the mean are either primarily intuitive or primarily instrumental. (Although the graph shows deviations as either positive [+] or negative [–], this is not to be seen as a value judgment of either pattern.) Whether the pattern is primarily instrumental, intuitive, or blended, the griever with the greatest number of available and useful strategies has a distinct advantage over the griever limited to just a few. This may become a special burden for those instrumental or intuitive grievers at the more extreme ends of the continuum. However, blended grievers, whose experience of grief may be more diffuse than either intuitive or instrumental grievers, may also be burdened by their style since the blended style may necessitate a greater repertoire of adaptive strategies.

FIGURE 3.5 Normal distribution with standard deviations.

In Section II of the book, the origins of the patterns of grief are explored. For now, remember the following caveats:

- Patterns of grief exist along a continuum; that is, it is extremely rare to observe either a “pure” intuitive or a “pure” instrumental pattern of grief. Although there are key elements that are useful in discriminating between the two, these represent differences in degree, not kind. The vast majority of individual grievers experience and express their grief in ways common to both patterns but toward either end of the continuum. Whether grievers are intuitive or instrumental or blended depends on whether their internal experiences are more affective than cognitive or a fairly equal portion of both. It also depends on their willingness to talk about their feelings rather than their issues, and whether they are more focused on difficulties related to their internal experiences or to solving external problems created by the loss. Since it is rare to find grievers at either extreme, the safest description for almost all would be blended. But this denies us the usefulness of understanding that patterns are, indeed, different. Likewise, it would be foolish to arbitrarily select a point on the continuum and declare that “beyond this point blended becomes instrumental or intuitive.” Perhaps the wisest course is to understand that most grievers are more instrumental than intuitive or more intuitive than instrumental, rather than as either instrumental or intuitive or blended.

- A few grievers may respond to different losses with a different pattern of grieving, and to refer to a person as an instrumental griever or an intuitive griever or a blended griever can be misleading. However, most individuals are relatively consistent in their pattern of grief, whether it is primarily instrumental, intuitive, or blended, although their position on the instrumental–intuitive continuum may change through life. This may be particularly true of the griever’s choice of primary and secondary adaptive strategies. In other words, a griever may be more instrumental in his grieving earlier in life and become less instrumental in grieving over time. The same holds for those whose primary pattern of grieving is intuitive. This is consistent with the theorizing of Carl Jung (1920), who believed that those aspects of ourselves that are not dominant during the first half of life tend to find more expression as we age. Jung embraced the concept of balance, believing that we achieve balance between all the different aspects of ourselves over the course of a lifetime (see Chapter 6, Sidebar 6.3).

- For the sake of clarity and brevity, those who consistently display elements inherent to the instrumental pattern will be referred to as instrumental grievers, those who follow the intuitive pattern as intuitive grievers, and those whose experiences and expressions are a balanced combination as blended grievers. The reader should continue to view the patterns along a continuum.

- Whether a griever skillfully negotiates the challenges presented by being bereaved and moves on with living, or flounders and stagnates, remaining forever compromised by his or her experience, depends on whether he or she chooses and successfully implements effective adaptive strategies. Both instrumental and intuitive grievers may choose ways of adapting to loss that are more or less complementary to their natural style of grieving, and result in a more positive than negative outcome. Unfortunately, the griever who chooses and maintains a primary adaptive strategy that is incongruent with his or her inner experience does so at peril. Also, both intuitive and instrumental grievers must find additional ways to express themselves that may be unfamiliar. For instrumental grievers, this means they must find outlets that allow them to vent whatever internal levels of affect they experience. On the other hand, intuitive grievers need to discover ways to facilitate the expression of their cognitions as well as their feelings. Thus, effective adaptive strategies must accomplish two goals:

- They must facilitate the expression of the griever’s dominant inner modality of experience (affect for the intuitive griever, cognition for the instrumental style).

- They should also expedite expression of the subordinate modality of experience. This means expressing feelings for the instrumental griever and cognitive-based activity for the intuitive pattern.

- Although the blended pattern equally combines the elements of the intuitive and instrumental patterns, it should not be seen as a goal or ideal form of grief. No pattern is superior or inferior to the other. It is the individual griever’s choice and implementation of effective adaptive strategies that determine how well he or she adjusts to a loss.

Now that the basic patterns have been identified, along with certain stipulations, the balance of this chapter will examine, in detail, the intuitive pattern of grief. In-depth discussion of the instrumental pattern follows in the next chapter.

☐ Intuitive Grief

Intuitive grievers experience their losses deeply. Feelings are varied and intense and loosely follow the descriptions of acute grief that have been cited so frequently in the literature (see, for example, Lindemann, 1944). Emotions vary, ranging from shock and disbelief to overwhelming sorrow and a sense of loss of self-control. The intuitive griever may experience grief as a series or waves of acutely painful feelings. Intuitive grievers often find themselves without energy and motivation. Their expressions of grief truly mirror their inner experiences. Anguish and tears are almost constant companions.

Intuitive grievers gain strength and solace from openly sharing their inner experiences with others—especially other grievers. Some intuitive grievers are very selective about their confidantes and, consequently, may not seek help from a larger group. Others seek out larger groups, especially those with similar types of losses. For intuitive grievers, a grief expressed is a grief experienced (or a burden shared is half a burden). Because openly expressing and sharing feelings is traditionally identified as a female trait, intuitive grieving is usually associated with women. Of course, this is not always the case; male intuitive grievers grieve in ways similar to female intuitive grievers.

Some intuitive grievers may seek professional counseling to have the intensity of their feelings and responses validated as being part of a normal grief process. This is especially true of the male intuitive griever, whose experiences and expressions run counter to gender role expectations. Other intuitive grievers, both male and female, look to counseling to provide new, effective adaptive strategies or to augment current strategies.

☐ Characteristics of Intuitive Grieving

The following are summaries of the features of grief and grieving that differentiate the intuitive from the instrumental griever. Intuitive grievers differ from their instrumental counterparts in three ways. First, their experience of grief is different. This may represent the most significant difference between the two styles. Second, the intuitive griever expresses his or her grief differently. This expression usually reflects a third difference between patterns: choice of primary adaptive strategies. Before proceeding, it should be remembered that these elements are not separate entities. Rather, these features are part of a system of functioning and interact with one another to produce the emotional response that is grief.

The Experience of Grief: Intensity of Affect Over Cognitions

Intuitive grievers experience grief, above all, as feelings. As illustrated in the following, their descriptions of these feelings reveal vivid brief glimpses of intense inner pain, helplessness, hopelessness, and loneliness.

Oh Christ, what am I going to do? I have an ache, an ache in my stomach. An emptiness, a feeling sometimes that there’s no inside to me. Like this sculpture a friend of mine made before he died of a second heart attack. It’s a man with no chest, that’s the way he felt. I look at that, that’s the way I feel. It’s a state beyond aloneness. When you lose somebody, you can have a feeling of missing the person you’ve lost. But then you can go beyond that, to almost a personal annihilation. And I don’t know that I haven’t visited that second place sometimes. Where I feel that it’s not that I simply lost Carol, but that I’ve lost …

I sometimes have the feeling where is she? She’s coming home, this is a bad dream. It has an unreal quality to it. Maybe the process of grief is to make reality out of what doesn’t feel real. It seems like it couldn’t have happened. In the mornings, it feels so strange to be … Often, we would have tea together. In the evening, we would have something to eat. We would talk to each other—you know—and I miss her. I miss her desperately. I mean, there’s no mystique to the nuts and bolts of living alone for me. But I miss her, I miss her presence, I miss her physically, I miss her, I miss, I mean I want to, I want, when something has happened, I want to talk to her, I want to tell her something, usually something very funny, and sometimes I talk to her, but I usually start to cry when I do, very quickly. (Campbell & Silverman, 1996, See page)

This voice of pain belonged to George, a widower, and is an excerpt from an interview presented in the book Widower by Scott Campbell and Phyllis R. Silverman (1996). Although the book focuses on gender differences and tends to be biased in favor of the ways most women grieve and against male grievers (Martin, 1988), it contains many vivid descriptions of bereavement. George describes most of his experiences as feelings, such as “I sometimes have the feeling where is she?” and “Maybe the process of grief is to make reality out of what doesn’t feel real.” For George, his inner life is primarily one of feeling. Like most intuitive grievers, George responds more to internal cues, which are experienced as feelings, rather than to thoughts. In fact, for the intuitive griever, thoughts and feelings are one and the same. In this way, intuitive grievers are probably more “in touch” with their feelings than instrumental grievers.

There is a tremendous depth and intensity of feeling in George’s reflection of his wife’s death. An intuitive griever’s feelings are dominant, powerful, and enduring. They are the primary features of grieving. In his classic children’s work, Charlotte’s Web (1952), E. B. White described Wilbur’s response to hearing of Charlotte’s impending death: “Hearing this, Wilbur threw himself down in an agony of pain and sorrow. Great sobs racked his body. He heaved and grunted with desolation. ‘Charlotte,’ he moaned. ‘Charlotte! My true friend!’” (See page).

Intuitive grievers are also unable or unwilling to distance themselves from feelings expressed by others. These grievers cry right along with other grievers who may be crying while telling their story. In this way, intuitive grievers may experience feelings either directly or vicariously from sharing the feelings of another who is expressing his grief.

The Expression of Grief: A Grief Expressed Is a Grief Experienced

The outward expression of the intuitive griever mirrors his or her inner experience. The pain of loss is often expressed through tears, and ranges from quiet weeping to sobbing to wailing. Additional features include depressed mood, confusion, anxiety, loss of appetite, inability to concentrate, and anger and irritability.

It has been said, “Grief isn’t real until it’s shared with someone else.” This speaker certainly had the intuitive griever in mind. So did William Shakespeare when he wrote, “Give sorrow words: the grief that does not speak/Whispers the o’er-fraught heart and bids it break” (Macbeth, Act IV, Scene iii). These are commonly expressed sentiments. For example, most mental health professionals subscribe, at least in part, to the “talking cure” for the treatment of grief. Likewise, bereavement support groups foster sharing one’s burden of grief with others, discussing it openly and often. Of course, these same bereavement support groups can be social outlets as well. Simply being with other people can be comforting. Thus, we are making a distinction between “social behavior,” which encompasses vast numbers of activities and experiences, and “social disclosure” of one’s inner experiences. It is possible to maintain privacy about feelings and still benefit from the company of others.

Intuitive grievers want and need to discuss their feelings. They often do this by “working through” their grief. Summarizing the traditionalists’ (Bowlby, 1980; Parkes & Weiss, 1983) position on “working through,” Wortman and Silver (1989) make the following point:

Implicit in this assumption is the notion that individuals need to focus on and “process” what has happened and that attempts to deny the implications of the loss, or block feelings or thoughts about it, will ultimately be unproductive. (p. 351)

For the intuitive griever, talking about his or her experience is tantamount to having the experience. This retelling the story and reenacting the pain is a necessary part of grieving and an integral part of the intuitive pattern of grieving. It also represents the intuitive griever’s going “with” the grief experience.

Primary Adaptive Strategies: Going “With” the Experience

Going “with” the experience means centering activities on the experience of grief itself. Intuitive grievers structure their actions by responding to their feelings. The intuitive griever’s need and desire to talk about his or her feelings is the most prominent example of this. Other examples include the griever’s efforts to find time and space for tears, seeking help, sharing time with others who are bereaved, and offering heartfelt condolences to those grievers whose losses may be more recent. This is not to say that intuitive grievers neglect their responsibilities toward others. For instance, intuitive grievers still find enough energy to care for their families, friends, and other dependents. But this means putting their grieving on hold. Thus, intuitive grievers must supplement their primary adaptive strategy of going with their experience with channeling sufficient energy to accomplish meaningful and necessary goals.

Intuitive grievers expend most of their energies coming to terms with and expressing their feelings; this may mean diverting energy from normal activities. They may require more time to rechannel their energies to routine activities, such as self-care, work, and volunteer activities. For example, D. G. Cable (personal communication, February 13, 1998) provided the following instance illustrating how neglecting one’s health is potentially dangerous and may need to be discussed with the griever.

Theresa sought a counselor’s help after her husband died suddenly. As the counselor listened attentively to Theresa’s story, he noticed how pale she was, how her hands trembled, and how short of breath she was. He asked several times if she had seen her physician. The woman seemed not to hear the question. Finally, as their first session came to a close, the counselor confronted Theresa with her physical condition. He stated, “Before I will see you again in counseling, you must make an appointment with and see your doctor.” The woman stared at him for several seconds and then, in a sheepish tone replied, “I am a physician, and I know you are right. I just haven’t cared or wanted to know about the state of my own health.”

Intuitive grievers are also less likely than instrumental grievers to “problem find,” to seek out potential problems and solve them. Because so much of their energy is focused on their internal experience, intuitive grievers may appear to outwardly adjust more slowly to their losses. This is not necessarily so. Intuitive grievers are adapting to their losses by going with their feelings. The following case example illustrates how intuitive grievers find outlets for expressing their feelings.

Nathan had a secret: his twice-weekly visits to a therapist’s office where, for 50 minutes, he sobbed. He needed to keep this activity from his coworkers and friends (who were primarily one and the same) in order to keep his job.

Nathan had always wanted to be a fireman and, unlike most kids, he followed his dream. He began volunteering as a “fire scout” when he was 12 years old, washing his beloved trucks and running errands around the firehouse. As soon as he turned 18 he applied and was accepted to his state’s fire school. Now, at 25 years of age, he was living his dream as a professional firefighter. His only problem was that he had always been “sensitive,” and sensitivity was not one of the attributes expected—or tolerated—by his fire chief (an ex-Marine who honestly believed that tears were for “sissies”). When his mother died unexpectedly, Nathan found himself overwhelmed with feelings. Several weeks after her death, he was sobbing alone in the station locker room when the chief walked in. He ordered Nathan to “pull yourself together” and warned him that if he (the chief) was not confident that Nathan could handle a crisis that he would suspend him. Unfortunately, home was not a sanctuary either, since Nathan shared an apartment with two other firefighters.

Desperate to gain control of his feelings, Nathan sought help. After explaining his dilemma to the therapist and sobbing while talking about his mother the two made a contract that permitted Nathan as much of the session time as needed for him to simply cry. Knowing that for at least 50 minutes a week he had a safe haven for his tears gave Nathan the strength to hide his feelings from others.

Nathan’s adaptive strategy was successful, since it afforded him the opportunity to grieve openly. Nathan found a way to go with his grief.

Secondary Adaptive Strategies: Handling Problems, Meeting Challenges

Since the majority of grief energy infuses the intuitive griever’s feelings, there is less energy available to activate the cognitive and physical domains of experience. (Spirituality, both as it is experienced and practiced, is highly individual and is not a useful tool for discerning patterns.) Nonetheless, intuitive grievers do have cognitive and physical responses to loss and must find ways to express these facets of their experience.

Cognitively, intuitive grievers may experience prolonged periods of confusion, lack of concentration, disorientation, and disorganization. This often impairs their ability to work or complete complicated tasks. In fact, intuitive grievers must find ways to master their thinking in order to fulfill important roles and activities such as parenting or settling an estate.

Physically, intuitive grievers experience grief energy in any number of ways; however, two physical experiences seem to dominate. First, the griever may feel exhausted. Intense expressions of feelings like crying or venting anger can fatigue the griever, as can unusual responsibilities, such as preparing for the funeral or single parenting. Likewise, fitful sleeping and a poor diet can contribute to fatigue.

Second, intuitive grievers may be aware of physical energy manifesting as increased arousal. This is the hallmark of anxiety—an individual’s awareness of a heightened sense of arousal. In turn, anxiety that remains unchecked may exacerbate the griever’s fatigue. Thus, intuitive grievers should explore ways to augment their energy stores. They must also develop strategies for coping with heightened anxiety.

In summary, the following describes the behaviors associated with the intuitive pattern of grief:

- Feelings are intensely experienced.

- Expressions such as crying and lamenting mirror inner experience.

- Successful adaptive strategies facilitate the experience and expression of feelings.

- There are prolonged periods of confusion, inability to concentrate, disorganization, and disorientation.

- Physical exhaustion and/or anxiety may result.

☐ Notes

1. A loss could be appraised as positive—an end to extreme suffering—in which case the grief reaction would be modulated as well.

2. Remember that the use of the term “emotion” reflects the modalities of the individual’s response tendency. Affect (feelings) is just one component of emotion. The other components are cognition, physicality, and spirituality.

3. Some colleagues have expressed misgivings about the potential outcomes for instrumental grievers. This concern involves the question of whether instrumental grievers are better at hiding from their own feeling or are simply better than intuitive grievers at hiding their feelings from others. If so, does this lead to successfully resolving and adapting to one’s losses? Kagan (1994), points out that the major problem in studying emotion regulation is to separate the intensity of the emotion from the effectiveness of the regulatory effort. Thus, a suggestion would be to reframe any questions about the prophylactic effects of instrumental grief in the following way: Are instrumental grievers better at regulating their feelings about their losses or are their feelings simply less intense to begin with, or both?

4. Other authors have used different terms, e.g., antecedent-focused, responsefocused (see Gross & Munoz, 1995).