Fatigue is one of the most common complaints related by pts. It usually refers to nonspecific sense of a low energy level, or the feeling that near exhaustion is reached after relatively little exertion. Fatigue should be distinguished from true neurologic weakness, which describes a reduction in the normal power of one or more muscles (Chap. 59). It is not uncommon for pts, especially the elderly, to present with generalized failure to thrive, which may include components of fatigue and weakness, depending on the cause.

Because the causes of generalized fatigue are numerous, a thorough history, review of systems (ROS), and physical examination are paramount to narrow the focus to likely causes. The history and ROS should focus on the temporal onset of fatigue and its progression. Has it lasted days, weeks, or months? Activities of daily living, exercise, eating habits/appetite, sexual practices, and sleep habits should be reviewed. Features of depression or dementia should be sought. Travel history and possible exposures to infectious agents should be reviewed, along with the medication list. The ROS may elicit important clues as to organ system involvement. The past medical history may elucidate potential precursors to the current presentation, such as previous malignancy or cardiac problems. The physical exam should specifically assess weight and nutritional status, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal masses, pallor, rash, heart failure, new murmurs, painful joints or trigger points, and evidence of weakness or neurologic abnormalities. A finding of true weakness or paralysis should prompt consideration of neurologic disorders (Chap. 59).

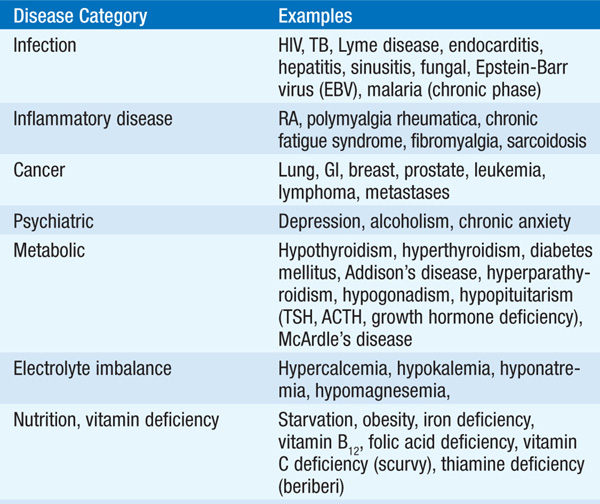

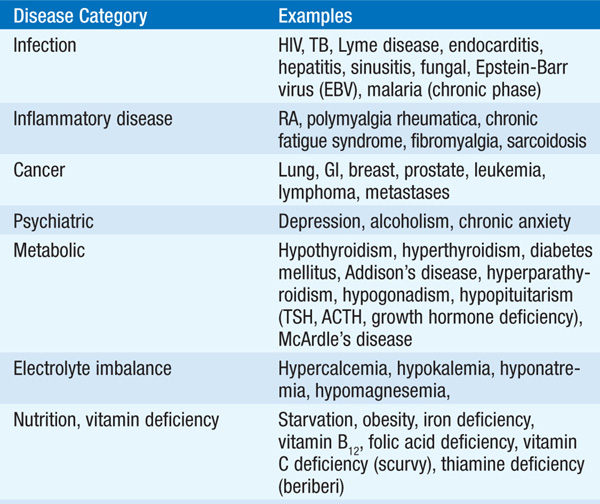

Determining the cause of fatigue can be one of the most challenging diagnostic problems in medicine because the differential diagnosis is very broad, including infection, malignancy, cardiac disease, endocrine disorders, neurologic disease, depression, or serious abnormalities of virtually any organ system, as well as side effects of many medications (Table 35-1). Symptoms of fever and weight loss will focus attention on infectious causes, whereas symptoms of progressive dyspnea might point toward cardiac, pulmonary, or renal causes. A presentation that includes arthralgia suggests the possibility of a rheumatologic disorder. A previous malignancy, thought to be cured or in remission, may have recurred or metastasized widely. A previous history of valvular heart disease or cardiomyopathy may identify a condition that has decompensated. Treatment for Graves’ disease may have resulted in hypothyroidism. Changes in medication should always be pursued, whether discontinued or recently started. Almost any new medication has the potential to cause fatigue. However, a temporal association with a new medication should not eliminate other causes, as many pts may have received new medications in an effort to address their complaints. Medications and their dosages should be carefully assessed, especially in elderly pts, in whom polypharmacy and inappropriate or misunderstood dosing is a frequent cause of fatigue. The time course for presentation is also valuable. Indolent presentations over months to years are more likely to be associated with slowly progressive organ failure or endocrinopathies, whereas a more rapid course over weeks to months suggests infection or malignancy.

TABLE 35-1 POTENTIAL CAUSES OF GENERALIZED FATIGUE

Laboratory testing and imaging should be guided by the history and physical exam. However, a CBC with differential, electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, glucose, calcium, and LFTs are useful in most pts with undifferentiated fatigue, as these tests will rule out many causes and may provide clues to unsuspected disorders. Similarly, a CXR is useful to evaluate many possible disorders rapidly, including heart failure, pulmonary disease, or occult malignancy that may be detected in the lungs or bony structures. Subsequent testing should be based on the initial results and clinical assessment of the likely differential diagnoses. For example, a finding of anemia would dictate the need to assess whether it has features of iron deficiency or hemolysis, thereby narrowing potential causes. Hyponatremia might be caused by SIADH, hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, or medications or by underlying cardiac, pulmonary, liver, or renal dysfunction. An elevated WBC count would raise the possibility of infection or malignancy. Thus, the approach is generally one of gathering information in a serial but cost-effective manner to narrow the differential diagnosis progressively.

Treatment should be based on the diagnosis, if known. Many conditions, such as metabolic, nutritional, or endocrine disorders, can be corrected quickly by appropriate treatment of the underlying causes. Specific treatment can also be initiated for many infections, such as TB, sinusitis, or endocarditis. Pts with chronic conditions such as COPD, heart failure, renal failure, or liver disease may benefit from interventions that enhance organ function or correct associated metabolic problems, and it may be possible to gradually improve physical conditioning. In pts with cancer, fatigue may be caused by chemotherapy or radiation and may resolve with time; treatment of associated anemia, nutritional deficiency, hyponatremia, or hypercalcemia may increase energy levels. Replacement therapy in endocrine deficiencies typically results in improvement. Treatment of depression or sleep disorders, whether a primary cause of fatigue or secondary to a medical disorder, may be beneficial. Withdrawal of medications that potentially contribute to fatigue should be considered, recognizing that other medications may need to be substituted for the underlying condition. In elderly pts, appropriate medication dose adjustments (typically lowering the dose) and restricting the regimen to only essential drugs may improve fatigue.

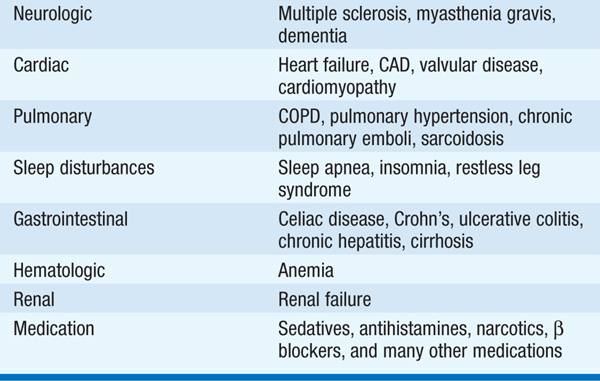

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is characterized by debilitating fatigue and several associated physical, constitutional, and neuropsychological complaints. The majority of pts (~75%) are women, generally 30–45 years old. The CDC has developed diagnostic criteria for CFS based upon symptoms and the exclusion of other illnesses (Table 35-2). The cause is uncertain, although clinical manifestations often follow an infectious illness (Q fever, Lyme disease, mononucleosis or another viral illness). Many studies have attempted, without success, to link CFS to infection with EBV, a retrovirus (including a murine leukemia virus–related retrovirus), or an enterovirus. Physical or psychological stress is also often identified as a precipitating factor. Depression is present in half to two-thirds of pts, and some experts believe that CFS is fundamentally a psychiatric disorder.

TABLE 35-2 CDC CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME

CFS remains a diagnosis of exclusion, and no laboratory test can establish the diagnosis or measure its severity. CFS does not appear to progress but typically has a protracted course. The median annual recovery rate is 5% (range, 0–31%) with an improvement rate of 39% (range, 8–63%).

The management of CFS commences with acknowledgement by the physician that the pt’s daily functioning is impaired. The pt should be informed of the current understanding of CFS (or lack thereof) and be offered general advice about disease management. NSAIDs alleviate headache, diffuse pain, and feverishness. Antihistamines or decongestants may be helpful for symptoms of rhinitis and sinusitis. Although the pt may be averse to psychiatric diagnoses, features of depression and anxiety may justify treatment. Nonsedating antidepressants improve mood and disordered sleep and may attenuate the fatigue. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET) have been found to be effective treatment strategies in some pts.

For a more detailed discussion, see Aminoff MJ: Weakness and Paralysis, Chap. 22, p. 181; Czeisler CA, Winkelman JW, Richardson GS: Sleep Disorders, Chap. 27, p. 213; Robertson RG, Jameson LJ: Involuntary Weight Loss, Chap. 80, p. 641; Bleijenberg G, van der Meer JWM: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Chap. 389, p. 3519; Reus VI: Mental Disorders, Chap. 391, p. 3529, in HPIM-18.