Disorders of sleep are among the most common problems seen by clinicians. More than one-half of adults experience at least intermittent sleep disturbances, and 50–70 million Americans suffer from a chronic sleep disturbance.

APPROACH TO THE PATIENT Sleep Disorders

Pts may complain of (1) difficulty in initiating and maintaining sleep (insomnia); (2) excessive daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or tiredness; (3) behavioral phenomena occurring during sleep [sleepwalking, rapid eye movement (REM) behavioral disorder, periodic leg movements of sleep, etc.]; or (4) circadian rhythm disorders associated with jet lag, shift work, and delayed sleep phase syndrome. A careful history of sleep habits and reports from the sleep partner (e.g., heavy snoring, falling asleep while driving) are a cornerstone of diagnosis. Pts with excessive sleepiness should be advised to avoid all driving until effective therapy has been achieved. Completion of a day-by-day sleep-work-drug log for at least 2 weeks is often helpful. Work and sleep times (including daytime naps and nocturnal awakenings) as well as drug and alcohol use, including caffeine and hypnotics, should be noted each day. Objective sleep laboratory recording is necessary to evaluate specific disorders such as sleep apnea and narcolepsy.

Insomnia, or the complaint of inadequate sleep, may be subdivided into difficulty falling asleep (sleep onset insomnia), frequent or sustained awakenings (sleep maintenance insomnia), early morning awakenings (sleep offset insomnia), or persistent sleepiness/fatigue despite sleep of adequate duration (nonrestorative sleep). An insomnia complaint lasting one to several nights is termed transient insomnia and is typically due to situational stress or a change in sleep schedule or environment (e.g., jet lag). Short-term insomnia lasts from a few days up to 3 weeks; it is often associated with more protracted stress such as recovery from surgery or short-term illness. Long-term (chronic) insomnia lasts for months or years and, in contrast to short-term insomnia, requires a thorough evaluation for underlying causes. Chronic insomnia is often a waxing and waning disorder, with spontaneous or stress-induced exacerbations.

All insomnias can be exacerbated and perpetuated by behaviors that are not conducive to initiating or maintaining sleep. Inadequate sleep hygiene is characterized by a behavior pattern prior to sleep, and/or a bedroom environment, that is not conducive to sleep. In preference to hypnotic medications, the pt should attempt to avoid stressful activities before bed, reserve the bedroom environment for sleeping, and maintain regular rising times.

Acute insomnia can occur after a change in the sleeping environment (e.g., in an unfamiliar hotel or hospital bed) or before or after a significant life event or anxiety-provoking situation. Treatment is symptomatic, with intermittent use of hypnotics and resolution of the underlying stress.

These pts are preoccupied with a perceived inability to sleep adequately at night. Rigorous attention should be paid to sleep hygiene and correction of counterproductive, arousing behaviors before bedtime. Behavioral therapies are the treatment of choice.

Caffeine is probably the most common pharmacologic cause of insomnia. Alcohol and nicotine can also interfere with sleep, despite the fact that many pts use these agents to relax and promote sleep. A number of prescribed medications, including antidepressants, sympathomimetics, and glucocorticoids, can produce insomnia. In addition, severe rebound insomnia can result from the acute withdrawal of hypnotics, especially following use of high doses of benzodiazepines with a short half-life. For this reason, doses of hypnotics should be low to moderate and prolonged drug tapering is encouraged.

Pts with restless legs syndrome (RLS) complain of creeping dysesthesias deep within the calves or feet associated with an irresistible urge to move the affected limbs; symptoms are typically worse at night. Iron deficiency and renal failure can cause secondary RLS. One-third of pts have multiple affected family members. Treatment is with dopaminergic drugs (pramipexole 0.25–0.5 mg daily at 8 P.M. or ropinirole 0.5–4.0 mg daily at 8 P.M.). Periodic limb movements of sleep (PLMS) consists of stereotyped extensions of the great toe and dorsiflexion of the foot recurring every 20–40 s during non-REM sleep. Treatment options include dopaminergic medications or benzodiazepines.

A variety of neurologic disorders produce sleep disruption through both indirect, nonspecific mechanisms (e.g., neck or back pain) or by impairment of central neural structures involved in the generation and control of sleep itself. Common disorders to consider include dementia from any cause, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, and migraine.

Approximately 80% of pts with mental disorders complain of impaired sleep. The underlying diagnosis may be depression, mania, an anxiety disorder, or schizophrenia.

In asthma, daily variation in airway resistance results in marked increases in asthmatic symptoms at night, especially during sleep. Treatment of asthma with theophylline-based compounds, adrenergic agonists, or glucocorticoids can independently disrupt sleep. Inhaled glucocorticoids that do not disrupt sleep may provide a useful alternative to oral drugs. Cardiac ischemia is also associated with sleep disruption; the ischemia itself may result from increases in sympathetic tone as a result of sleep apnea. Pts may present with complaints of nightmares or vivid dreams. Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea can also occur from cardiac ischemia that causes pulmonary congestion exacerbated by the recumbent posture. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis, hyperthyroidism, menopause, gastroesophageal reflux, chronic renal failure, and liver failure are other causes.

TREATMENT Insomnia

INSOMNIA WITHOUT IDENTIFIABLE CAUSE Primary insomnia is a diagnosis of exclusion.

• Treatment directed toward behavior therapies for anxiety and negative conditioning; pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy for mood/anxiety disorders; an emphasis on good sleep hygiene; and intermittent hypnotics for exacerbations of insomnia.

• Cognitive therapy emphasizes understanding the nature of normal sleep, the circadian rhythm, the use of light therapy, and visual imagery to block unwanted thought intrusions.

• Behavioral modification involves bedtime restriction, set schedules, and careful sleep environment practices.

• Judicious use of benzodiazepine receptor agonists with short half-lives can be effective; options include zaleplon (5–20 mg), zolpidem (5–10 mg), triazolam (0.125–0.25 mg), eszopiclone (1–3 mg). Limit use to 2–4 weeks maximum for acute insomnia or intermittent use for chronic.

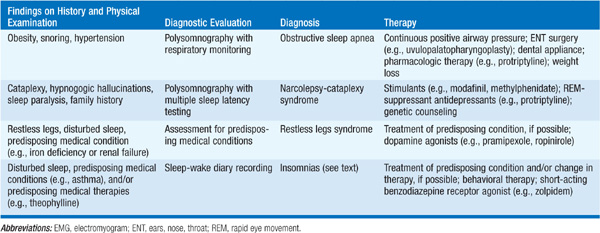

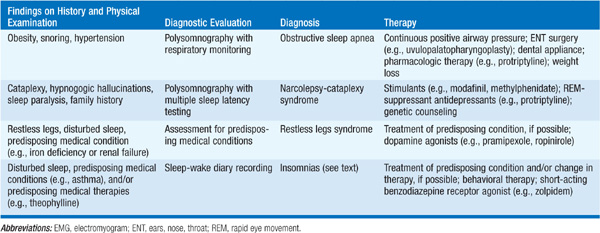

Differentiation of sleepiness from subjective complaints of fatigue may be difficult. Quantification of daytime sleepiness can be performed in a sleep laboratory using a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT), the repeated daytime measurement of sleep latency under standardized conditions. Common causes are summarized in Table 62-1.

TABLE 62-1 EVALUATION OF THE PATIENT WITH THE COMPLAINT OF EXCESSIVE DAYTIME SOMNOLENCE

Respiratory dysfunction during sleep is a common cause of excessive daytime sleepiness and/or disturbed nocturnal sleep, affecting an estimated 2–5 million individuals in the United States. Episodes may be due to occlusion of the airway (obstructive sleep apnea), absence of respiratory effort (central sleep apnea), or a combination of these factors (mixed sleep apnea). Obstruction is exacerbated by obesity, supine posture, sedatives (especially alcohol), nasal obstruction, and hypothyroidism. Sleep apnea is particularly prevalent in overweight men and in the elderly and is undiagnosed in 80–90% of affected individuals. Treatment consists of correction of the above factors, positive airway pressure devices, oral appliances, and sometimes surgery (Chap. 146).

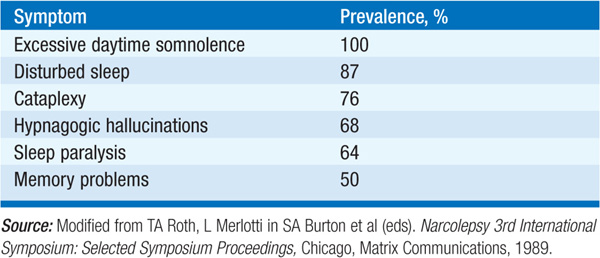

A disorder of excessive daytime sleepiness and intrusion of REM-related sleep phenomena into wakefulness (cataplexy, hypnagogic hallucinations, and sleep paralysis). Cataplexy, the abrupt loss of muscle tone in arms, legs, or face, is precipitated by emotional stimuli such as laughter or sadness. Symptoms of narcolepsy (Table 62-2) typically begin in the second decade, although the onset ranges from ages 5–50. The prevalence is 1 in 4000. Narcolepsy has a genetic basis; almost all narcoleptics with cataplexy are positive for HLA DQB1*0602. Hypothalamic neurons containing the neuropeptide hypocretin (orexin) regulate the sleep/wake cycle and loss of these cells, possibly due to autoimmunity, has been implicated in narcolepsy. Diagnosis is made with sleep studies confirming a short daytime sleep latency and a rapid transition to REM sleep.

TABLE 62-2 PREVALENCE OF SYMPTOMS IN NARCOLEPSY

TREATMENT Narcolepsy

• Somnolence is treated with modafinil (200–400 mg/d given as a single dose).

• Older stimulants such as methylphenidate (10 mg bid to 20 mg qid) or dextroamphetamine (10 mg bid) are alternatives, particularly in refractory pts.

• Cataplexy, hypnagogic hallucinations, and sleep paralysis respond to the tricyclic antidepressants protriptyline (10–40 mg/d) and clomipramine (25–50 mg/d) and to the selective serotonin uptake inhibitor fluoxetine (10–20 mg/d). Alternatively, γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) given at bedtime, and 4 h later, is effective in reducing daytime cataplectic episodes.

• Adequate nocturnal sleep time and the use of short naps are other useful preventative measures.

Insomnia or hypersomnia may occur in disorders of sleep timing rather than sleep generation. Such conditions may be (1) organic—due to a defect in the hypothalamic circadian pacemaker or its input from entraining stimuli, or (2) environmental—due to a disruption of exposure to entraining stimuli (light/dark cycle). Examples of the latter include jet-lag disorder and shift work. Shift work sleepiness can be treated with modafinil (200 mg, taken 30–60 min before the start of each night shift) as well as properly timed exposure to bright light. Safety programs should promote education about sleep and increase awareness of the hazards associated with night work.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome is characterized by late sleep onset and awakening with otherwise normal sleep architecture. Bright-light phototherapy in the morning hours or melatonin therapy during the evening hours may be effective.

Advanced sleep phase syndrome moves sleep onset to the early evening hours with early morning awakening. These pts may benefit from bright-light phototherapy during the evening hours. Some autosomal dominant cases result from mutations in a gene (PER2) involved in regulation of the circadian clock.

For a more detailed discussion, see Czeisler CA, Winkleman JW, Richardson GS: Sleep Disorders, Chap. 27, p. 213, in HPIM-18.