Enlargement of the prostate is nearly universal in aging men. Hyperplasia usually begins by age 45 years, occurs in the area of the prostate gland surrounding the urethra, and produces urinary outflow obstruction. Symptoms develop on average by age 65 in whites and 60 in blacks. Symptoms develop late because hypertrophy of the bladder detrusor compensates for ureteral compression. As obstruction progresses, urinary stream caliber and force diminish, hesitancy in stream initiation develops, and postvoid dribbling occurs. Dysuria and urgency are signs of bladder irritation (perhaps due to inflammation or tumor) and are usually not seen in prostate hyperplasia. As the postvoid residual increases, nocturia and overflow incontinence may develop. Common medications such as tranquilizing drugs and decongestants, infections, or alcohol may precipitate urinary retention. Because of the prevalence of hyperplasia, the relationship to neoplasia is unclear.

On digital rectal exam (DRE), a hyperplastic prostate is smooth, firm, and rubbery in consistency; the median groove may be lost. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels may be elevated but are ≤10 ng/mL unless cancer is also present (see below). Cancer may also be present at lower levels of PSA.

Asymptomatic pts do not require treatment, and those with complications of urethral obstruction such as inability to urinate, renal failure, recurrent urinary tract infection, hematuria, or bladder stones clearly require surgical extirpation of the prostate, usually by transurethral resection (TURP). However, the approach to the remaining pts should be based on the degree of incapacity or discomfort from the disease and the likely side effects of any intervention. If the pt has only mild symptoms, watchful waiting is not harmful and permits an assessment of the rate of symptom progression. If therapy is desired by the pt, two medical approaches may be helpful: terazosin, an α1-adrenergic blocker (1 mg at bedtime, titrated to symptoms up to 20 mg/d), relaxes the smooth muscle of the bladder neck and increases urine flow; finasteride (5 mg/d) or dutasteride (2.5 mg/d), inhibitors of 5α-reductase, block the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone and cause an average decrease in prostate size of ~24%. TURP has the greatest success rate but also the greatest risk of complications. Transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT) may be comparably effective to TURP. Direct comparison has not been made between medical and surgical management.

Prostate cancer has been diagnosed in 241,740 men in 2012 in the United States—an incidence comparable to that of breast cancer. About 28,170 men have died of prostate cancer in 2012. The early diagnosis of cancers in mildly symptomatic men found on screening to have elevated serum levels of PSA has complicated management. Like most other cancers, incidence is age-related. The disease is more common in blacks than whites. Symptoms are generally similar to and indistinguishable from those of prostate hyperplasia, but those with cancer more often have dysuria and back or hip pain. On histology, 95% are adenocarcinomas. Biologic behavior is affected by histologic grade (Gleason score).

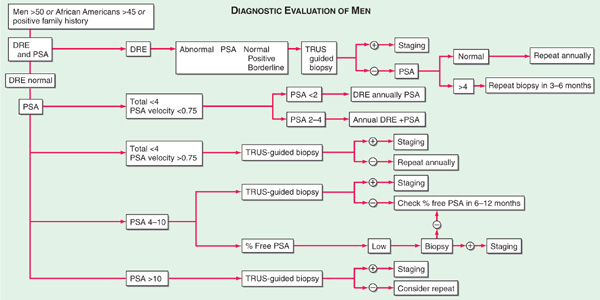

In contrast to hyperplasia, prostate cancer generally originates in the periphery of the gland and may be detectable on DRE as one or more nodules on the posterior surface of the gland, hard in consistency and irregular in shape. An approach to diagnosis is shown in Fig. 81-1. Those with a negative DRE and PSA ≤4 ng/mL may be followed annually. Those with an abnormal DRE or a PSA >10 ng/mL should undergo transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided biopsy. Those with normal DRE and PSA of 4.1–10 ng/mL may be handled differently in different centers. Some would perform TRUS and biopsy any abnormality or follow if no abnormality were found. Some would repeat the PSA in a year and biopsy if the increase over that period were >0.75 ng/mL. Other methods of using PSA to distinguish early cancer from hyperplasia include quantitating bound and free PSA and relating the PSA to the size of the prostate (PSA density). Perhaps one-third of persons with prostate cancer do not have PSA elevations.

FIGURE 81-1 The use of the annual digital rectal examination (DRE) and measurement of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) as guides for deciding which men should have transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided prostate biopsy. There are at least three schools of thought about what to do if the DRE is negative and the PSA is equivocal (4.1 to 10 ng/mL).

Lymphatic spread is assessed surgically; it is present in only 10% of those with Gleason grade 5 or lower and in 70% of those with grade 9 or 10. PSA level also correlates with spread; only 10% of those with PSA <10 ng/mL have lymphatic spread. Bone is the most common site of distant metastasis. Whitmore-Jewett staging includes A: tumor not palpable but detected at TURP; B: palpable tumor in one (B1) or both (B2) lobes; C: palpable tumor outside capsule; and D: metastatic disease.

For pts with stages A through C disease, surgery (radical retropubic prostatectomy) and radiation therapy (conformal 3-dimensional fields) are said to have similar outcomes; however, most pts are treated surgically. Both modalities are associated with impotence. Surgery is more likely to lead to incontinence. Radiation therapy is more likely to produce proctitis, perhaps with bleeding or stricture. Addition of hormonal therapy (goserelin) to radiation therapy of pts with localized disease appears to improve results. Pts usually must have a 5-year life expectancy to undergo radical prostatectomy. Stage A pts have survival identical to age-matched controls without cancer. Stage B and C pts have a 10-year survival of 82% and 42%, respectively.

Pts treated surgically for localized disease who develop rising PSA may undergo Prostascint scanning (antibody to a prostate-specific membrane antigen). If no uptake is seen, the pt is observed. If uptake is seen in the prostate bed, local recurrence is implied and external beam radiation therapy is delivered to the site. (If the pt was initially treated with radiation therapy, this local recurrence may be treated with surgery.) However, in most cases, a rising PSA after local therapy indicates systemic disease. It is not clear when to intervene in such pts.

For pts with metastatic disease, androgen deprivation is the treatment of choice. Surgical castration is effective, but most pts prefer to take leuprolide, 7.5 mg depot form IM monthly (to inhibit pituitary gonadotropin production), plus flutamide, 250 mg PO tid (an androgen receptor blocker). The value of added flutamide is debated. Alternative approaches include adrenalectomy, hypophysectomy, estrogen administration, and medical adrenalectomy with aminoglutethimide. The median survival of stage D pts is 33 months. Pts occasionally respond to withdrawal of hormonal therapy with tumor shrinkage. Second hormonal manipulations act by blocking androgen production in the tumor; abiraterone, a CYP17 inhibitor that blocks androgen synthesis and MDV3100, an antiandrogen, improve overall survival. Many pts who progress on hormonal therapy have androgen-independent tumors, often associated with genetic changes in the androgen receptor and new expression of bcl-2, which may contribute to chemotherapy resistance. Chemotherapy is used for palliation in prostate cancer. Mitoxantrone, estramustine, and taxanes, particularly cabazitaxel, appear to be active single agents, and combinations of drugs are being tested. Chemotherapy-treated pts are more likely to have pain relief than those receiving supportive care alone. Sipuleucel-T, an active specific immunotherapy, improves survival by about 4 months in hormone-refractory disease without producing any measureable change in the tumor. Bone pain from metastases may be palliated with strontium-89 or samarium-153. Bisphosphonates decrease the incidence of skeletal events.

Finasteride and dutasteride have been shown to reduce the incidence of prostate cancer by 25%, but no effect on overall survival has been seen with limited follow-up. In addition, the cancers that do occur appear to be shifted to higher Gleason grades, although follow-up is limited to assess the natural history.

For a more detailed discussion, see Scher HI: Benign and Malignant Diseases of the Prostate, Chap. 95, p. 796, in HPIM-18.