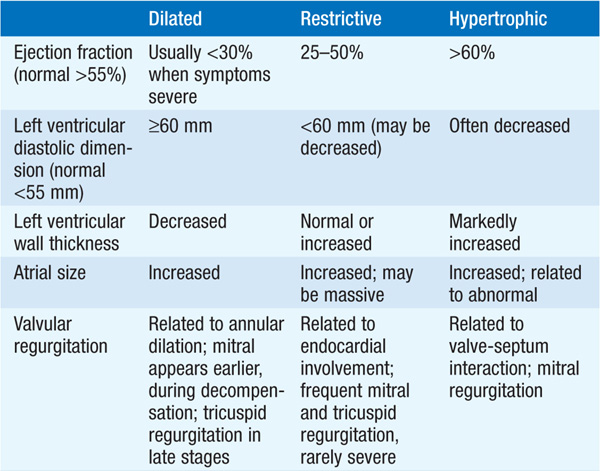

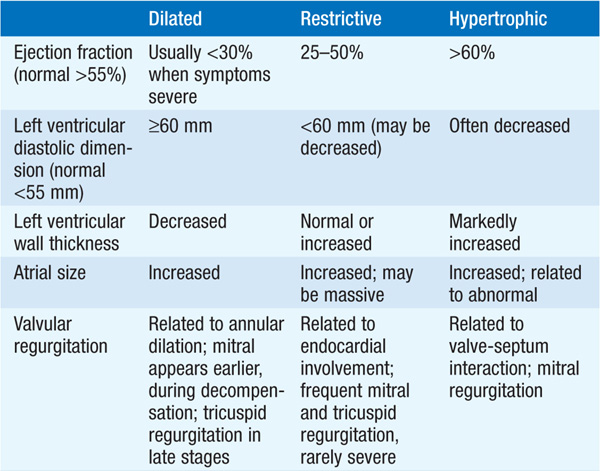

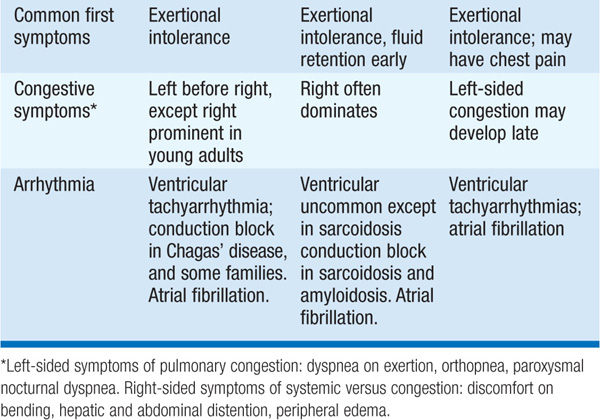

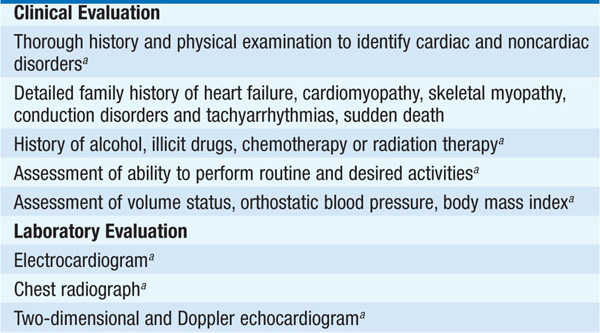

Cardiomyopathies are primary diseases of heart muscle. Table 124-1 summarizes distinguishing presenting features of the three major types of cardiomyopathy. Table 124-2 details the comprehensive initial evaluation of suspected cardiomyopathies.

TABLE 124-1 PRESENTATION WITH SYMPTOMATIC CARDIOMYOPATHY

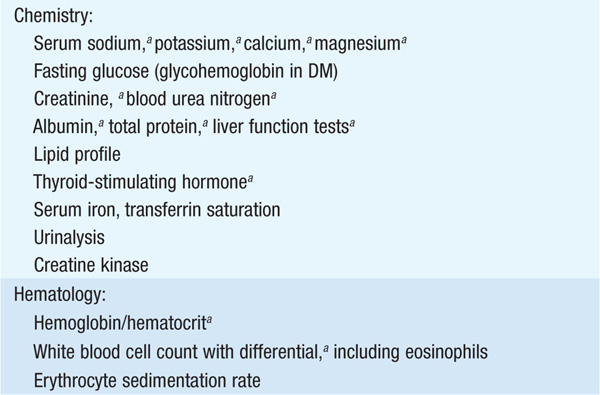

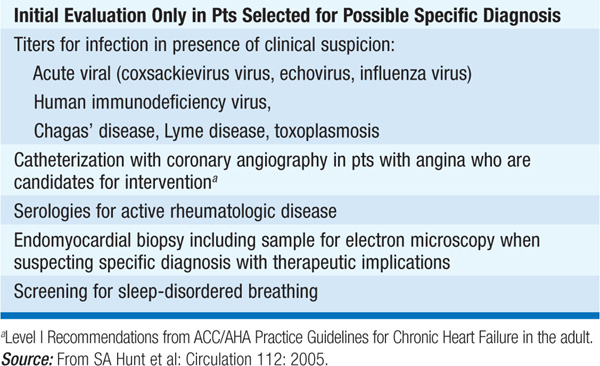

TABLE 124-2 INITIAL EVALUATION OF CARDIOMYOPATHY

Symmetrically dilated left ventricle (LV), with poor systolic contractile function; right ventricle (RV) commonly involved.

Approximately one-third of pts have a familial form, including those cases due to mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins. Other causes include previous myocarditis, toxins [ethanol, certain antineoplastic agents (doxorubicin, trastuzumab, imatinib mesylate)], connective tissue disorders, muscular dystrophies, “peripartum.” Impaired LV function owing to severe coronary disease/infarction or chronic aortic/mitral regurgitation may behave similarly.

Congestive heart failure (Chap. 133); tachyarrhythmias and peripheral emboli from LV mural thrombus occur.

Jugular venous distention (JVD), rales, diffuse and dyskinetic LV apex, S3, hepatomegaly, peripheral edema; murmurs of mitral and tricuspid regurgitation are common.

Left bundle branch block and ST-T-wave abnormalities common.

Cardiomegaly, pulmonary vascular redistribution, pulmonary effusions common.

LV and RV enlargement with globally impaired contraction. Regional wall motion abnormalities suggest coronary artery disease rather than primary cardiomyopathy.

Level elevated in heart failure/cardiomyopathy but not in pts with dyspnea due to lung disease.

TREATMENT Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Standard therapy of heart failure (Chap. 133): Diuretic for volume overload, vasodilator therapy with ACE inhibitor (preferred), angiotensin receptor blocker or hydralazine-nitrate combination shown to limit disease progression and improve longevity. Add beta blocker in most pts. Add spironolactone for pts with advanced heart failure. Consider chronic anticoagulation with warfarin if accompanying atrial fibrillation (AF), prior embolism, or recent large anterior MI. Antiarrhythmic drugs (e.g., amiodarone or dofetilide) may be useful to maintain sinus rhythm in pts with AF. Consider implanted cardioverter defibrillator for pts with > class III heart failure and LVEF <35%. For those with persistent class III–IV heart failure, LVEF <35%, and QRS duration >120 ms, consider biventricular pacing. Possible trial of immunosuppressive drugs, if active myocarditis present on RV biopsy (controversial as long-term efficacy has not been demonstrated). In selected pts, consider cardiac transplantation.

Increased myocardial stiffness impairs ventricular relaxation; diastolic ventricular pressures are elevated. Etiologies include infiltrative disease (amyloid, sarcoid, hemochromatosis, eosinophilic disorders), endomyocardial fibrosis, Fabry’s disease, and prior mediastinal irradiation.

Are of heart failure, although right-sided heart failure often predominates, with peripheral edema and ascites.

Predominantly signs of right-sided heart failure: JVD, hepatomegaly, peripheral edema, murmur of tricuspid regurgitation. Left-sided S4 is common.

Low limb lead voltage, sinus tachycardia, ST-T-wave abnormalities.

Mild LV enlargement.

Bilateral atrial enlargement; increased ventricular thickness (“speckled pattern”) in infiltrative disease, especially amyloidosis. Systolic function is usually normal but may be mildly reduced.

Increased LV and RV diastolic pressures with “dip and plateau” pattern; RV biopsy useful in detecting infiltrative disease (rectal or fat pad biopsy useful in diagnosis of amyloidosis).

Note: Must distinguish restrictive cardiomyopathy from constrictive pericarditis, which is surgically correctable. Thickening of pericardium in pericarditis usually apparent in CT or MRI.

TREATMENT Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

Salt restriction and diuretics ameliorate pulmonary and systemic congestion; digitalis is not indicated unless systolic function is impaired or atrial arrhythmias are present. Note: Increased sensitivity to digitalis in amyloidosis. Anticoagulation often indicated, particularly in pts with eosinophilic endomyocarditis. For specific therapy of hemochromatosis and sarcoidosis, see Chaps. 357 and 329, respectively, in HPIM-18.

Marked LV hypertrophy; often asymmetric, without underlying hypertension or valvular disease. Systolic function is usually normal; increased LV stiffness results in elevated diastolic filling pressures. Typically results from mutations in sarcomeric proteins (autosomal dominant transmission).

Secondary to elevated diastolic pressure, dynamic LV outflow obstruction (if present), and arrhythmias; dyspnea on exertion, angina, and presyncope; sudden death may occur.

Brisk carotid upstroke with pulsus bisferiens; S4, harsh systolic murmur along left sternal border, blowing murmur of mitral regurgitation at apex; murmur changes with Valsalva and other maneuvers (Chap. 119).

LV hypertrophy with prominent “septal” Q waves in leads I, aVL, V5–6. Periods of atrial fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia are often detected by Holter monitor.

LV hypertrophy, often with asymmetric involvement, especially of the septum or apex; LV contractile function typically excellent with small endsystolic volume. If LV outflow tract obstruction is present, systolic anterior motion (SAM) of mitral valve and midsystolic partial closure of aortic valve are present. Doppler shows early systolic accelerated blood flow through LV outflow tract.

TREATMENT Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Strenuous exercise should be avoided. Beta blockers, verapamil, or disopyramide used individually to reduce symptoms. Digoxin, other inotropes, diuretics, and vasodilators are generally contraindicated. Endocarditis antibiotic prophylaxis (Chap. 89) is necessary only in pts with a prior history of endocarditis. Antiarrhythmic agents, especially amiodarone, may suppress atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. However, consider implantable cardioverter defibrillator for pts with high-risk profile, e.g., history of syncope or aborted cardiac arrest, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, marked LVH (>3 cm), exertional hypotension, or family history of sudden death. In selected pts, LV outflow gradient can be reduced by controlled septal infarction by ethanol injection into the septal artery. Surgical myectomy may be useful in pts refractory to medical therapy.

Inflammation of the myocardium that may progress to chronic dilated cardiomyopathy, most commonly due to acute viral infection (e.g., parvovirus B19, coxsackievirus, adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus). Myocarditis may also develop in pts with HIV infection, hepatitis C or Lyme disease. Chagas’ disease is a common cause of myocarditis in endemic areas, typically Central and South America.

Fever, fatigue, palpitations; if LV dysfunction develops, symptoms of heart failure are present. Viral myocarditis may be preceded by URI.

Fever, tachycardia, soft S1; S3 common.

CK-MB isoenzyme and cardiac troponins may be elevated in absence of MI. Convalescent antiviral antibody titers may rise.

Transient ST-T-wave abnormalities.

Cardiomegaly

Depressed LV function; pericardial effusion present if accompanying pericarditis present. MRI demonstrates mid-wall gadolinium enhancement.

TREATMENT Myocarditis

Rest; treat as heart failure (Chap. 133); efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., steroids) has not been demonstrated except in isolated conditions such as sarcoidosis and giant cell myocarditis. In fulminant cases, cardiac transplantation may be indicated.

For a more detailed discussion, see Stevenson LW, Loscalzo J: Cardiomyopathy and Myocarditis, Chap. 238, p. 1951, in HPIM-18.