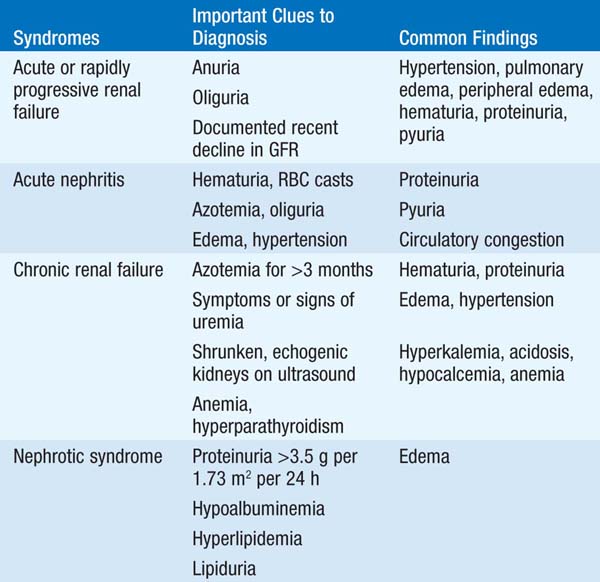

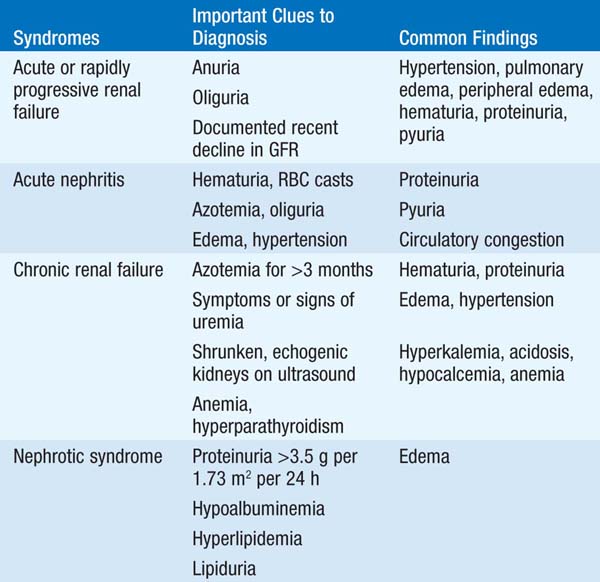

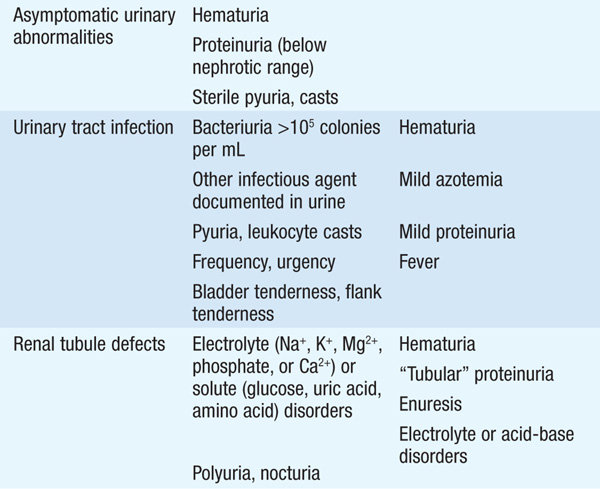

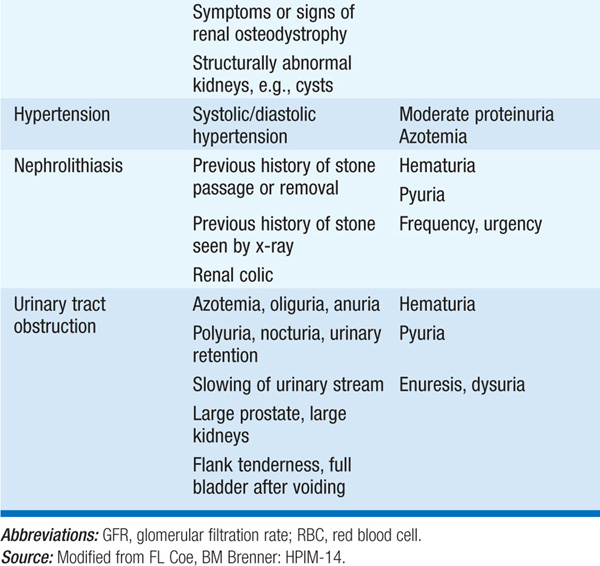

The approach to renal disease begins with recognition of particular syndromes on the basis of findings such as presence or absence of azotemia, proteinuria, hypertension, edema, abnormal urinalysis, electrolyte disorders, abnormal urine volumes, or infection (Table 147-1).

TABLE 147-1 INITIAL CLINICAL AND LABORATORY DATABASE FOR DEFINING MAJOR SYNDROMES IN NEPHROLOGY

Clinical syndrome is characterized by a rapid, severe decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) [rise in serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN)], usually with reduced urine output. Extracellular fluid expansion leads to edema, hypertension, and occasionally acute pulmonary edema. Hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, and acidosis are common. Etiologies include ischemia; nephrotoxic injury due to drugs, toxins, or endogenous pigments; sepsis; severe renovascular disease; glomerulonephritis (GN); interstitial nephritis, particularly allergic interstitial nephritis due to medications; thrombotic microangiopathy; or conditions related to pregnancy. Prerenal failure and postrenal failure are potentially reversible causes.

Defined as a >50% reduction in renal function, occurring over weeks to months. Broadly classified into three major subtypes on the basis of renal biopsy findings and pathophysiology: (1) immune complex–associated, e.g., in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); (2) “pauci-immune,” associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) specific for myeloperoxidase or proteinase-3; and (3) associated with anti–glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibodies, e.g., in Goodpasture’s syndrome.

Pts are initially nonoliguric and may have recent flulike symptoms (myalgias, low-grade fevers, etc.); later, oliguric renal failure with uremic symptoms supervenes. Hypertension is common, particularly in poststreptococcal GN. Symptoms of associated disorders may be prominent, e.g., arthritis/arthralgias in SLE or vasculitis. Pulmonary manifestations in ANCA- and anti-GBM-associated rapidly progressive GN range from asymptomatic infiltrates to life-threatening pulmonary hemorrhage. Urinalysis typically shows hematuria, proteinuria, and red blood cell (RBC) casts; however, while highly specific for GN, RBC casts are not a particularly sensitive finding.

Often called nephritic syndrome, classically caused by poststreptococcal GN. An acute illness with sudden onset of hematuria, edema, hypertension, oliguria, and elevated BUN and creatinine. Mild pulmonary congestion may be present. An antecedent or concurrent infection or multisystem disease may be causative, or glomerular disease may exist alone. Hematuria, proteinuria, and pyuria are usually present, and RBC casts confirm the diagnosis. Serum complement may be decreased in certain conditions.

Progressive permanent loss of renal function over months to years does not cause symptoms of uremia until GFR is reduced to about 10–15% of normal. Hypertension and/or edema may occur early. Later, manifestations include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, dysgeusia, insomnia, weight loss, weakness, paresthesia, pruritus, bleeding, serositis (typically pericarditis), anemia, acidosis, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperkalemia. Common causes include diabetes mellitus, severe hypertension, glomerular disease, urinary tract obstruction, vascular disease, polycystic kidney disease, and interstitial nephritis. Indications of chronicity include longstanding azotemia, anemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, shrunken kidneys, renal osteodystrophy by x-ray, or findings on renal biopsy (extensive glomerular sclerosis, arteriosclerosis, and/or tubulointerstitial fibrosis).

Defined as heavy albuminuria (>3.5 g/d in the adult) with or without edema, hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, and varying degrees of renal insufficiency. Can be idiopathic or due to drugs, infections, neoplasms, or multisystem or hereditary diseases. Complications include severe edema, thromboembolic events, infection, and protein malnutrition.

Hematuria may be due to neoplasms, stones, infection at any level of the urinary tract, sickle cell disease, or analgesic abuse. Renal parenchymal causes are suggested by RBC casts, proteinuria, and/or dysmorphic RBCs in urine. Pattern of gross hematuria may be helpful in localizing site. Hematuria with minimal or low-grade proteinuria is most commonly due to thin basement membrane nephropathy or IgA nephropathy. Modest proteinuria may be an isolated finding due to fever, exertion, congestive heart failure (CHF), or upright posture; renal causes include early stages of diabetes nephropathy, amyloidosis, or other causes of glomerular disease. Pyuria can be caused by urinary tract infection (UTI), interstitial nephritis, GN, or renal transplant rejection. “Sterile” pyuria can be associated with UTI treated with antibiotics, cyclophosphamide therapy, pregnancy, genitourinary trauma, prostatitis, cystourethritis, tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infections, and fungal infection.

Generally defined as >105 bacteria per mL of urine. Levels between 102 and 105/mL may indicate infection but are usually due to poor sample collection, especially if mixed flora are present. Adults at risk are sexually active women or anyone with urinary tract obstruction, vesicoureteral reflux, bladder catheterization, neurogenic bladder (associated with diabetes mellitus), or primary neurologic diseases. Prostatitis, urethritis, and vaginitis may be distinguished by quantitative urine culture. Flank pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, and chills indicate kidney infection, i.e., pyelonephritis. UTI is a common cause of sepsis, especially in the elderly and institutionalized.

Generally inherited, these include anatomic defects (polycystic kidneys, medullary cystic disease, medullary sponge kidney) detected in the evaluation of hematuria, flank pain, infection, or renal failure of unknown cause. Isolated or generalized defects of renal tubular salt, solute, acid, and water transport can also occur. The Fanconi syndrome is characterized by multiple defects in proximal tubular solute transport; cardinal features include generalized aminoaciduria, glycosuria with a normal serum glucose, and phosphaturia. The Fanconi syndrome can also encompass a proximal renal tubular acidosis, hypouricemia, hypokalemia, polyuria, hypovitaminosis D and hypocalcemia, and low-molecular-weight proteinuria. This syndrome can be hereditary (e.g., in Dent’s disease and cystinosis) or acquired, the latter due to drugs (ifosfamide, tenofovir, valproic acid), toxins (aristolochic acid), heavy metals, multiple myeloma, or amyloidosis. Hereditary hypokalemic alkalosis is typically caused by defects in ion transport by the thick ascending limb (Bartter’s syndrome) or the distal convoluted tubule (Gitelman’s syndrome); similar acquired defects can occur after exposure to aminoglycosides or cisplatin. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and renal tubular acidosis are caused by defects in distal tubular water and acid transport, respectively; these also have both hereditary and acquired forms. Lithium, prescribed for bipolar disease and related psychiatric disorders, is a very common cause of acquired nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.

Blood pressure >140/90 mmHg affects 20% of the U.S. adult population; when inadequately controlled, it is an important cause of cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, and CHF, and can contribute to the development of renal failure. Hypertension is usually asymptomatic until cardiac, renal, or neurologic symptoms appear; retinopathy or left ventricular hypertrophy (S4 heart sound, electrocardiographic or echocardiographic evidence) may be the only clinical sequelae. In most cases, hypertension is idiopathic and becomes evident between ages 25 and 45. Secondary hypertension is generally suggested by the following clinical scenarios: (1) severe or refractory hypertension, (2) a sudden increase in blood pressure over prior values, (3) onset prior to puberty, or (4) age <30 in a nonobese, non-African-American pt with a negative family history. Clinical clues may suggest specific causes. Hypokalemia suggests renovascular hypertension or primary hyperaldosteronism; paroxysmal hypertension with headache, diaphoresis, and palpitations can occur in pheochromocytoma.

Causes colicky pain, UTI, hematuria, dysuria, or unexplained pyuria. Stones may be found on routine x-ray of kidneys, ureter, and bladder (KUB); however, noncontrast helical CT, with 5-mm CT cuts, will pick up stones not detected by KUB x-ray and will furthermore assess for the presence of obstruction. Most are radiopaque Ca stones and are associated with high levels of urinary Ca, and/or oxalate excretion, and/or low levels of urinary citrate excretion. Staghorn calculi are large, branching, radiopaque stones within the renal pelvis due to recurrent infection. Uric acid stones are radiolucent. Urinalysis may reveal hematuria, pyuria, or pathologic crystals.

Causes variable symptoms depending on the underlying etiology and whether obstruction is acute or chronic, unilateral or bilateral, and complete or partial. It is an important, reversible cause of unexplained renal failure. Upper tract obstruction may be silent or produce flank pain, hematuria, and renal infection. Bladder symptoms or prostatism may be present in lower tract obstruction. Functional consequences include polyuria, anuria, nocturia, acidosis, hyperkalemia, and hypertension. A flank or suprapubic mass may be found on physical exam; an obstructed, enlarged bladder is typically dull to percussion. An increased post-void residual urine volume can be confirmed with bedside bladder scan or by ultrasound.