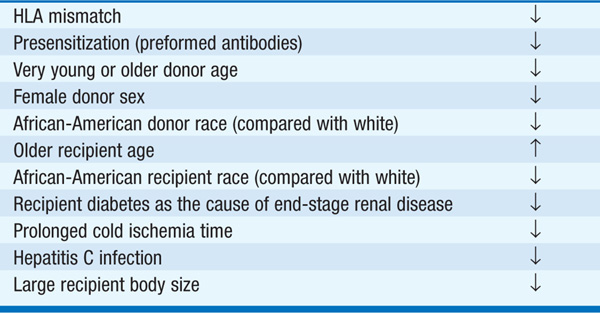

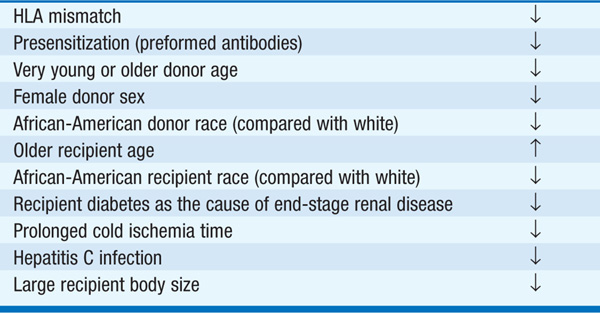

With the advent of more potent and well-tolerated immunosuppressive regimens and further improvements in short-term graft survival, renal transplantation remains the treatment of choice for most pts with end-stage renal disease. Results are best with living-related transplantation, in part because of optimized tissue matching and in part because waiting time can be minimized; ideally, these pts are transplanted prior to the onset of symptomatic uremia or indications for dialysis. Many centers now perform living-unrelated donor (e.g., spousal) transplants. Graft survival in these cases is far superior to that observed with cadaveric transplants, although less favorable than with living-related transplants. Factors that influence graft survival are outlined in Table 151-1. Pretransplant blood transfusion should be avoided, so as to reduce the likelihood of sensitization to incompatible HLA antigens; if transfusion is necessary, leukocyte-reduced irradiated blood is preferred. Contraindications to renal transplantation are outlined in Table 151-2. Overall, the current standard of care is that the pt should have >5 years of life expectancy to be eligible for a renal transplant, since the benefits of transplantation are only realized after a perioperative period in which the mortality rate is higher than in comparable pts on dialysis.

TABLE 151-1 SOME FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE GRAFT SURVIVAL IN RENAL TRANSPLANTATION

TABLE 151-2 CONTRAINDICATIONS TO RENAL TRANSPLANTATION

Immunologic rejection is the major hazard to the short-term success of renal transplantation. Rejection may be (1) hyperacute (immediate graft dysfunction due to presensitization) or (2) acute (sudden change in renal function occurring within weeks to months). Rejection is usually detected by a rise in serum creatinine but may also lead to hypertension, fever, reduced urine output, and occasionally graft tenderness. A percutaneous renal transplant biopsy confirms the diagnosis. Treatment usually consists of a “pulse” of methylprednisolone (500–1000 mg/d for 3 days). In refractory or particularly severe cases, 7–10 days of a monoclonal antibody directed at human T lymphocytes may be given.

Maintenance immunosuppressive therapy usually consists of a three-drug regimen, with each drug targeted at a different stage in the immune response. The calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine and tacrolimus are the cornerstones of immunosuppressive therapy. The most potent of orally available agents, calcineurin inhibitors have vastly improved short-term graft survival. Side effects of cyclosporine include hypertension, hyper-kalemia, resting tremor, hirsutism, gingival hypertrophy, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia and gout, and a slowly progressive loss of renal function with characteristic histopathologic patterns (also seen in exposed recipients of heart and liver transplants). While the side effect profile of tacrolimus is generally similar to cyclosporine, there is a higher risk of hyperglycemia, a lower risk of hypertension, and occasional hair loss rather than hirsutism.

Prednisone is frequently used in conjunction with cyclosporine, at least for the first several months following successful graft function. Side effects of prednisone include hypertension, glucose intolerance, cushingoid features, osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, acne, and depression and other mood disturbances.

Mycophenolate mofetil has proved more effective than azathioprine in combination therapy with calcineurin inhibitors and prednisone. The major side effects of mycophenolate mofetil are gastrointestinal (diarrhea is most common); leukopenia (and thrombocytopenia to a lesser extent) develops in a fraction of pts.

Sirolimus is a newer immunosuppressive agent often used in combination with other drugs, particularly when calcineurin inhibitors are reduced or eliminated. Side effects include hyperlipidemia and oral ulcers.

Infection and neoplasia are important complications of renal transplantation. Infection is common in the heavily immunosuppressed host (e.g., cadaveric transplant recipient with multiple episodes of rejection requiring steroid pulses or monoclonal antibody treatment). The culprit organism depends in part on characteristics of the donor and recipient and timing following transplantation (Table 151-3). In the first month, bacterial organisms predominate. After 1 month, there is a significant risk of systemic infection with cytomegalovirus (CMV), particularly in recipients without prior exposure whose donor was CMV positive. Prophylactic use of ganciclovir or valacyclovir can reduce the risk of CMV disease. Later on, there is a substantial risk of fungal and related infections, especially in pts who are unable to taper prednisone to <20–30 mg/d. Daily low-dose trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole is effective at reducing the risk of Pneumocystis carinii infection.

TABLE 151-3 THE MOST COMMON OPPORTUNISTIC INFECTIONS IN RENAL TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS

The polyoma group of DNA viruses (BK, JC, SV40) can be activated by immunosuppression. Reactivation of BK is associated with a typical pattern of renal inflammation, BK nephropathy, which can lead to loss of the allograft; therapy typically involves reduction of immunosuppression to aid in clearance of the reactivated virus.

Epstein-Barr virus–associated lymphoproliferative disease is the most important neoplastic complication of renal transplantation, especially in pts who receive polyclonal (antilymphocyte globulin, used at some centers for induction of immunosuppression) or monoclonal antibody therapy. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin are also more common in this population.

For a more detailed discussion, see Chandraker A, Milford EL, Sayegh MH: Transplantation in the Treatment of Renal Failure, Chap. 282, p. 2327, in HPIM-18.