CHAPTER 154

Urinary Tract Infections and Interstitial Cystitis

URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

Definitions

The term urinary tract infection (UTI) encompasses a variety of clinical entities: cystitis (symptomatic disease of the bladder), pyelonephritis (symptomatic disease of the kidney), prostatitis (symptomatic disease of the prostate), and asymptomatic bacteriuria (ABU). Uncomplicated UTI refers to acute disease in nonpregnant outpatient women without anatomic abnormalities or instrumentation of the urinary tract; complicated UTI refers to all other types of UTI.

Epidemiology

UTI occurs far more commonly in females than in males, although obstruction from prostatic hypertrophy causes men >50 years old to have an incidence of UTI comparable to that among women of the same age.

• 50–80% of women have at least one UTI during their lifetime, and 20–30% of women have recurrent episodes.

• Risk factors for acute cystitis include recent use of a diaphragm with spermicide, frequent sexual intercourse, a history of UTI, diabetes mellitus, and incontinence; many of these factors also increase the risk of pyelonephritis.

Microbiology

In the United States, Escherichia coli accounts for 75–90% of cystitis isolates; Staphylococcus saprophyticus for 5–15%; and Klebsiella species, Proteus species, Enterococcus species, Citrobacter species, and other organisms for 5–10%.

• The spectrum of organisms causing uncomplicated pyelonephritis is similar, with E. coli predominating.

• Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., enterococci and Staphylococcus aureus) and yeasts are also important pathogens in complicated UTI.

Pathogenesis

In the majority of UTIs, bacteria establish infection by ascending from the urethra to the bladder. Continuing ascent up the ureter to the kidney is the pathway for most renal parenchymal infections.

• The pathogenesis of candiduria is distinct in that the hematogenous route is common.

• The presence of Candida in the urine of a noninstrumented immunocompetent pt implies either genital contamination or potentially widespread visceral dissemination.

Clinical Manifestations

When a UTI is suspected, the most important issue is to classify it as ABU; as uncomplicated cystitis, pyelonephritis, or prostatitis; or as complicated UTI.

• Asymptomatic bacteriuria is diagnosed when a screening urine culture performed for a reason unrelated to the genitourinary tract is incidentally found to contain bacteria, but the pt has no local or systemic symptoms referable to the urinary tract.

• Cystitis presents with dysuria, urinary frequency, and urgency; nocturia, hesitancy, suprapubic discomfort, and gross hematuria are often noted as well. Unilateral back or flank pain and fever are signs that the upper urinary tract is involved.

• Pyelonephritis presents with fever, lower-back or costovertebral-angle pain, nausea, and vomiting. Bacteremia develops in 20–30% of cases.

– Papillary necrosis can occur in pts with obstruction, diabetes, sickle cell disease, or analgesic nephropathy.

– Emphysematous pyelonephritis is particularly severe, is associated with the production of gas in renal and perinephric tissues, and occurs almost exclusively in diabetic pts.

– Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis occurs when chronic urinary obstruction (often by staghorn calculi), together with chronic infection, leads to suppurative destruction of renal tissue.

• Prostatitis can be either infectious or noninfectious; noninfectious cases are far more common. Acute bacterial prostatitis presents with dysuria, urinary frequency, fever, chills, symptoms of bladder outlet obstruction, and pain in the prostatic, pelvic, or perineal area.

• Complicated UTI presents as symptomatic disease in a man or woman with an anatomic predisposition to infection, with a foreign body in the urinary tract, or with factors predisposing to a delayed response to therapy.

Diagnosis

The clinical history itself has a high predictive value in diagnosing uncomplicated cystitis; in a pt presenting with both dysuria and urinary frequency in the absence of vaginal discharge, the likelihood of UTI is 96%.

• A urine dipstick test positive for nitrite or leukocyte esterase can confirm the diagnosis of uncomplicated cystitis in pts with a high pretest probability of disease.

• The detection of bacteria in a urine culture is the diagnostic gold standard for UTI. A colony count threshold of >102 bacteria/mL is more sensitive (95%) and specific (85%) than a threshold of 105/mL for the diagnosis of acute cystitis in women with symptoms of cystitis.

TREATMENT Urinary Tract Infections

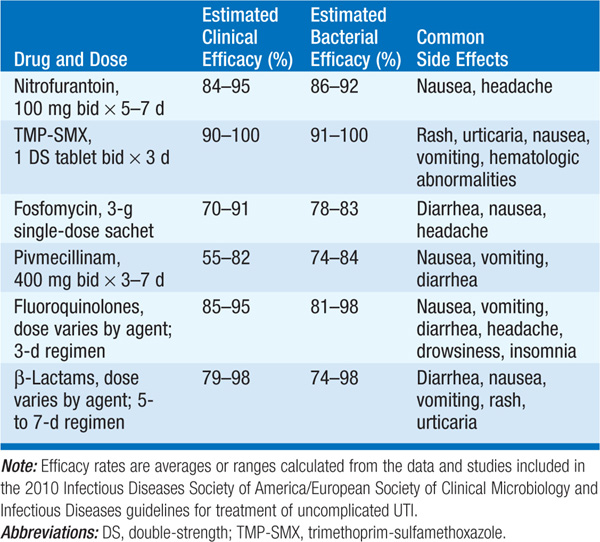

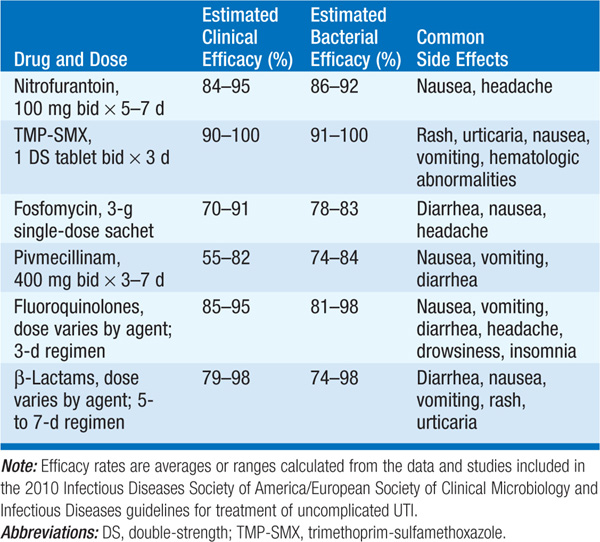

• Uncomplicated cystitis in women See Table 154-1 for effective the rapeutic regimens.

TABLE 154-1 TREATMENT STRATEGIES FOR ACUTE UNCOMPLICATED CYSTITIS

– Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) has been recommended as first-line treatment for acute cystitis, but should be avoided in regions with resistance rates >20%.

– Nitrofurantoin is another first-line agent with low rates of resistance.

– Fluoroquinolones should be used only when other antibiotics are not suitable because of increasing resistance or their role in prompting nosocomial outbreaks of Clostridium difficile infection.

– Except for pivmecillinam, β-lactam agents are associated with lower rates of pathogen eradication and higher rates of relapse.

• Pyelonephritis Given high rates of TMP-SMX-resistant E. coli, fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, 500 mg PO bid for 7 days) are first-line agents for the treatment of acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis. Oral TMP-SMX (one double-strength tablet bid for 14 days) is effective against susceptible uropathogens.

• UTI in pregnant women Nitrofurantoin, ampicillin, and the cephalosporins are considered relatively safe in early pregnancy.

• UTI in men In men with apparently uncomplicated UTI, a 7- to 14-day course of a fluoroquinolone or TMP-SMX is recommended.

– If acute bacterial prostatitis is suspected, antibiotics should be initiated after urine and blood are obtained for cultures.

– Therapy can be tailored to urine culture results and should be continued for 2–4 weeks; a 4- to 6-week course is often necessary for chronic bacterial prostatitis.

• Asymptomatic bacteriuria ABU should be treated only in pregnant women, in pts undergoing urologic surgery, and perhaps in neutropenic pts and renal transplant recipients; antibiotic choice is guided by culture results.

• Catheter-associated UTI Urine culture results are essential to guide therapy.

– Replacing the catheter during treatment is generally necessary. Candiduria, a common complication of indwelling catheterization, resolves in ~1/3 of cases with catheter removal.

– Treatment (fluconazole, 200–400 mg/d for 14 days) is recommended for pts who have symptomatic cystitis or pyelonephritis and for those who are at high risk for disseminated disease.

Prevention of Recurrent UTI

Women experiencing symptomatic UTIs ≥2 times a year are candidates for prophylaxis—either continuous or postcoital—or pt-initiated therapy. Continuous prophylaxis and postcoital prophylaxis usually entail low doses of TMP-SMX, a fluoroquinolone, or nitrofurantoin. Pt-initiated therapy involves supplying the pt with materials for urine culture and for self-medication with a course of antibiotics at the first symptoms of infection.

Prognosis

In the absence of anatomic abnormalities, recurrent infection in children and adults does not lead to chronic pyelonephritis or to renal failure.

INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS

Interstitial cystitis (painful bladder syndrome) is a chronic condition characterized by pain perceived to be from the urinary bladder, urinary urgency and frequency, and nocturia.

Epidemiology

In the United States, 2–3% of women and 1–2% of men have interstitial cystitis. Among women, the average age at onset is the early forties, but the range is from childhood through the early sixties.

Etiology

The etiology remains unknown.

• Theoretical possibilities include chronic bladder infection, inflammatory factors such as mast cells, autoimmunity, increased permeability of the bladder mucosa, and abnormal pain sensitivity.

• However, few data support any of these factors as an inciting cause.

Clinical Manifestations

The cardinal symptoms of pain (often at ≥2 sites), urinary urgency and frequency, and nocturia occur in no consistent order. Symptoms can begin acutely or gradually.

• Unlike pelvic pain arising from other sources, pain caused by interstitial cystitis is exacerbated by bladder filling and relieved by bladder emptying.

• 85% of pts void >10 times per day; some do so as often as 60 times per day.

• Many pts with interstitial cystitis have comorbid functional somatic syndromes (e.g., fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, vulvodynia, migraine).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the presence of appropriate symptoms and the exclusion of diseases with a similar presentation (e.g., diseases that manifest with pelvic pain and/or urinary symptoms, functional somatic syndromes with urinary symptoms); physical exam and laboratory findings are insensitive and/or nonspecific. Cystoscopy may reveal an ulcer (10% of pts) or petechial hemorrhages after bladder distension, but neither of these findings is specific.

TREATMENT Interstitial Cystitis

The goal of therapy is the relief of symptoms, which often requires a multifaceted approach (e.g., education, dietary changes, medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or amitriptyline, pelvic-floor physical therapy, and treatment of associated functional somatic syndromes).

For a more detailed discussion, see Gupta K, Trautner BW: Urinary Tract Infections, Pyelonephritis, and Prostatitis, Chap. 288, p. 2387, in HPIM-18.