CHAPTER 164

Chronic Hepatitis

A group of disorders characterized by a chronic inflammatory reaction in the liver for at least 6 months.

OVERVIEW

ETIOLOGY

Hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis D virus (HDV, delta agent), drugs (methyldopa, nitrofurantoin, isoniazid, dantrolene), autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

HISTOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION

Chronic hepatitis can be classified by grade and stage. The grade is a histologic assessment of necrosis and inflammatory activity and is based on examination of the liver biopsy. The stage of chronic hepatitis reflects the level of disease progression and is based on the degree of fibrosis (see Table 306-2, p. 2568, HPIM-18).

PRESENTATION

Wide clinical spectrum ranging from asymptomatic serum aminotransferase elevations to apparently acute, even fulminant, hepatitis. Common symptoms include fatigue, malaise, anorexia, low-grade fever; jaundice is frequent in severe disease. Some pts may present with complications of cirrhosis: ascites, variceal bleeding, encephalopathy, coagulopathy, and hyper-splenism. In chronic HBV or HCV and autoimmune hepatitis, extrahepatic features may predominate.

CHRONIC HEPATITIS B

Follows up to 1–2% of cases of acute hepatitis B in immunocompetent hosts; more frequent in immunocompromised hosts. Spectrum of disease: asymptomatic antigenemia, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular cancer; early phase often associated with continued symptoms of hepatitis, elevated aminotransferase levels, presence in serum of HBeAg and HBV DNA, and presence in liver of replicative form of HBV; later phase in some pts may be associated with clinical and biochemical improvement, disappearance of HBeAg and HBV DNA and appearance of anti-HBeAg in serum, and integration of HBV DNA into host hepatocyte genome. In Mediterranean and European countries as well as in Asia, a frequent variant is characterized by readily detectable HBV DNA, but without HBeAg (anti-HBeAg-reactive). Most of these cases are due to a mutation in the pre-C region of the HBV genome that prevents HBeAg synthesis (may appear during course of chronic wild-type HBV infection as a result of immune pressure and may also account for some cases of fulminant hepatitis B). Chronic hepatitis B ultimately leads to cirrhosis in 25–40% of cases (particularly in pts with HDV superinfection or the pre-C mutation) and hepatocellular carcinoma in many of these pts (particularly when chronic infection is acquired early in life).

EXTRAHEPATIC MANIFESTATIONS (IMMUNE COMPLEX–MEDIATED)

Rash, urticaria, arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa–like vasculitis, polyneuropathy, glomerulonephritis.

TREATMENT Chronic Hepatitis B

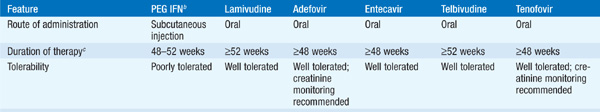

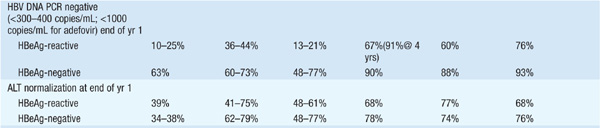

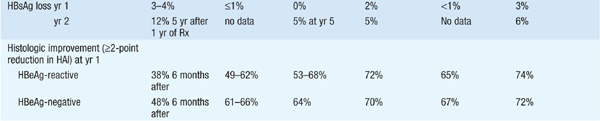

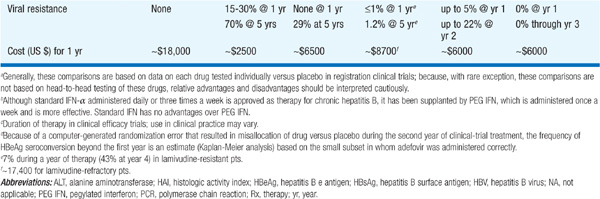

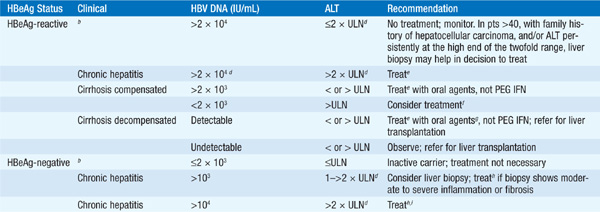

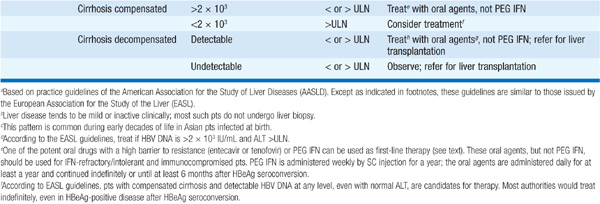

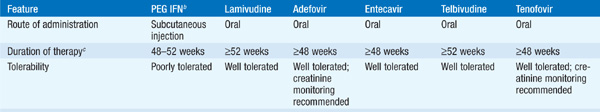

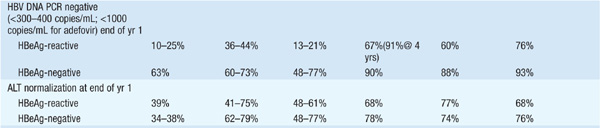

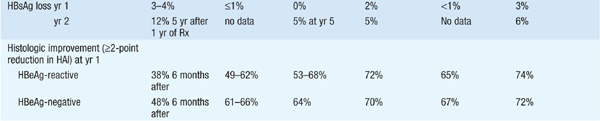

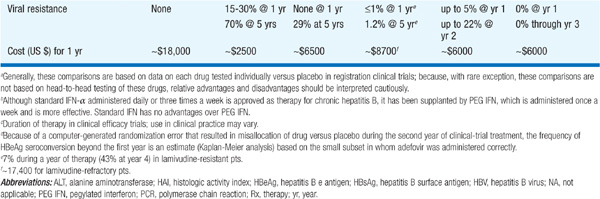

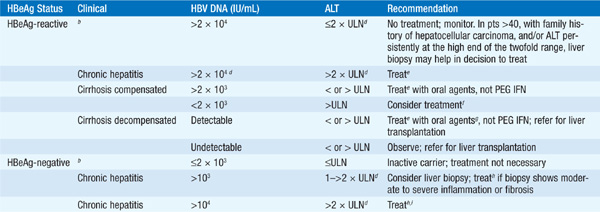

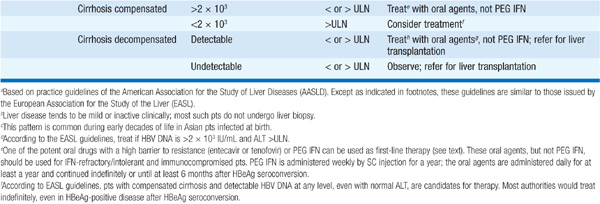

There are currently seven approved drugs for the treatment of chronic HBV: interferon α (IFN-α), pegylated interferon (PEG IFN), lamivudine, adefovir dipivoxil, entecavir, telbivudine, and tenofovir (see Table 164-1). Use of IFN-α has been supplanted by PEG-IFN. Table 164-2 summarizes recommendations for treatment of chronic HBV.

TABLE 164-1 COMPARISON OF PEGYLATED INTERFERON (PEG IFN), LAMIVUDINE, ADEFOVIR, ENTECAVIR, TELBIVUDINE, AND TENOFOVIR THERAPY FOR CHRONIC HEPATITIS Ba

TABLE 164-2 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TREATMENT OF CHRONIC HEPATITIS Ba

CHRONIC HEPATITIS C

Follows 50–70% of cases of transfusion-associated and sporadic hepatitis C. Clinically mild, often waxing and waning aminotransferase elevations; mild chronic hepatitis on liver biopsy. Extrahepatic manifestations include cryoglobulinemia, porphyria cutanea tarda, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and lymphocytic sialadenitis. Diagnosis confirmed by detecting anti-HCV in serum. May lead to cirrhosis in ≥20% of cases after 20 years.

TREATMENT Chronic Hepatitis C

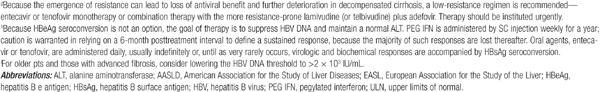

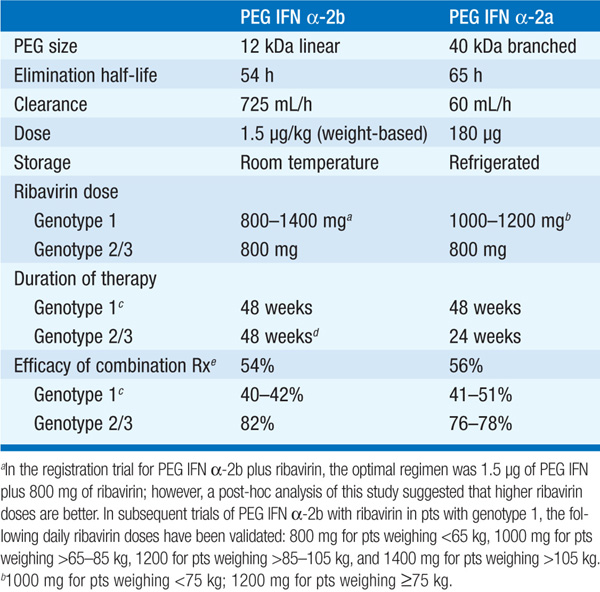

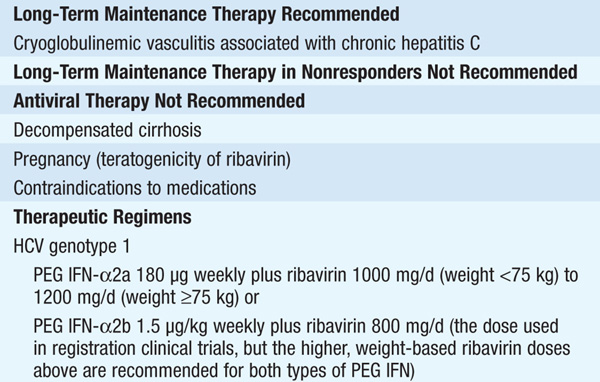

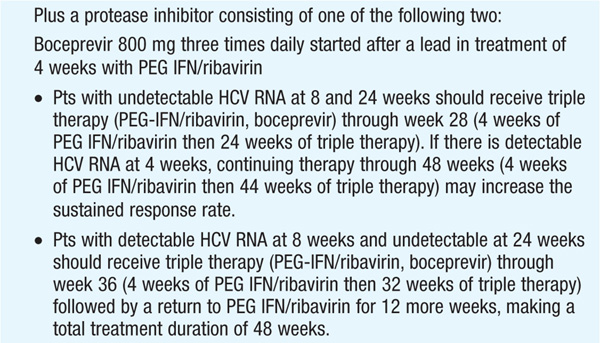

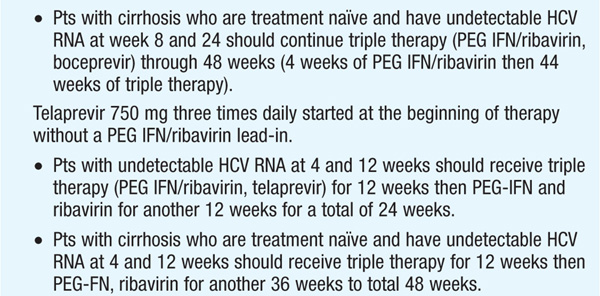

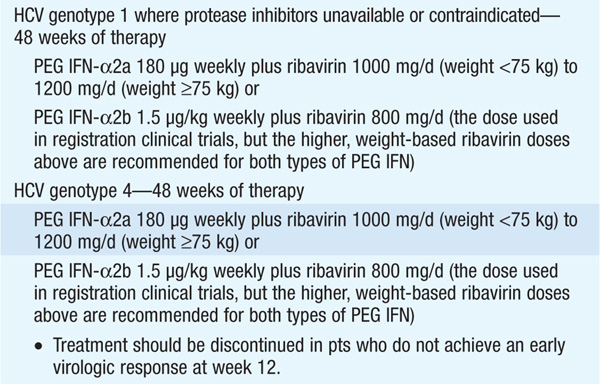

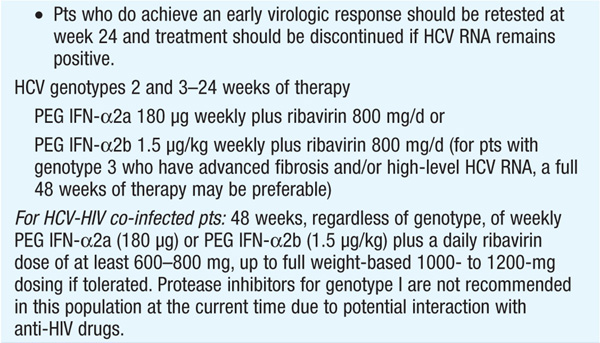

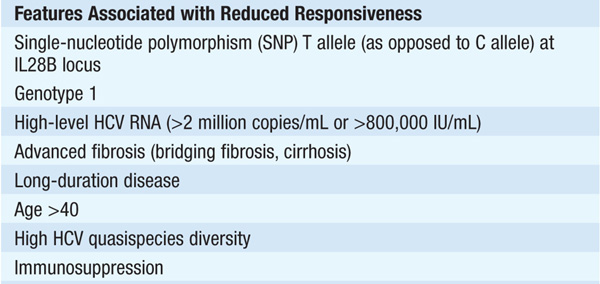

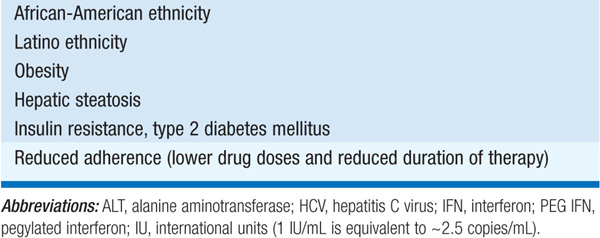

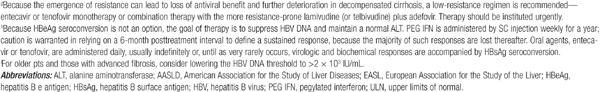

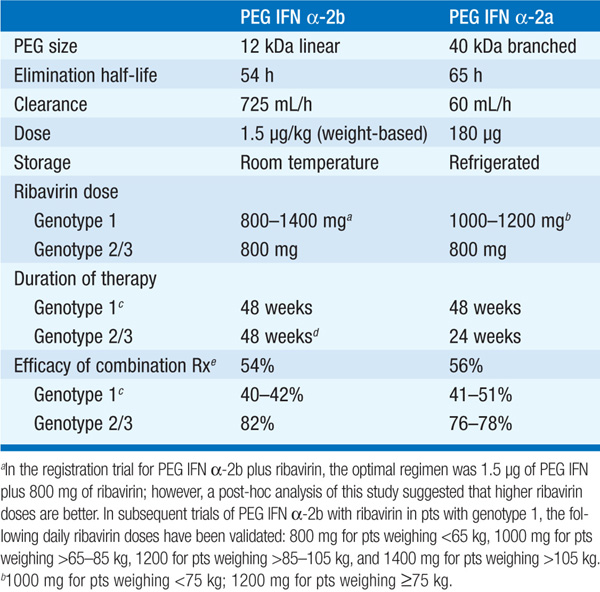

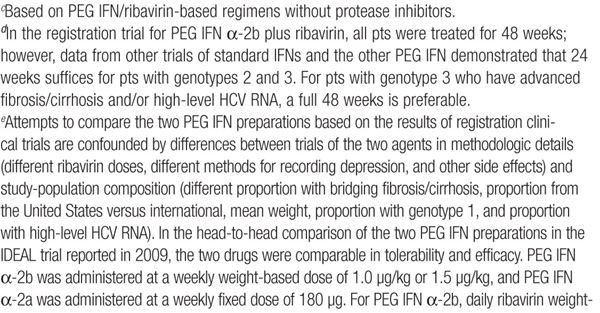

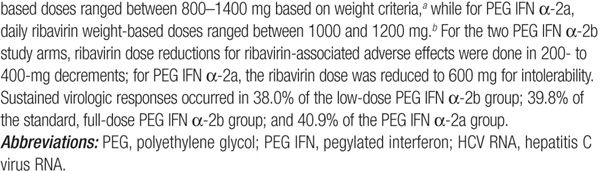

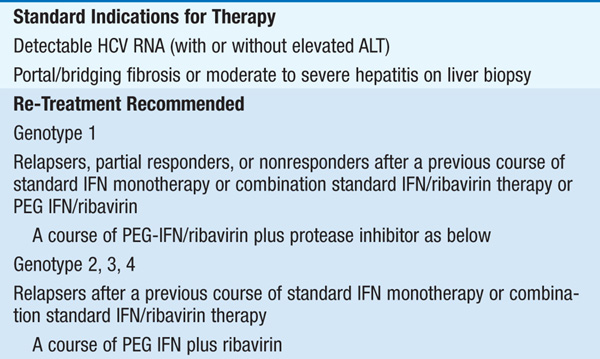

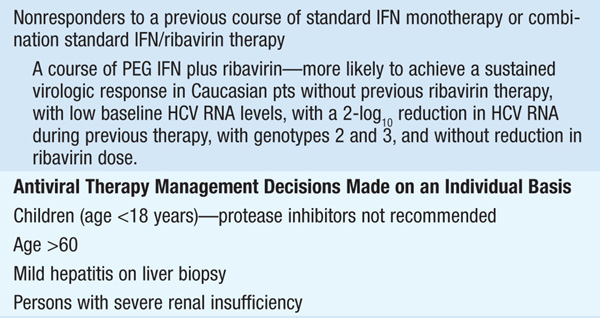

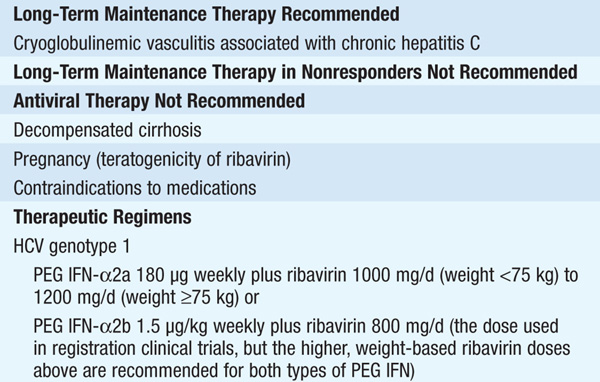

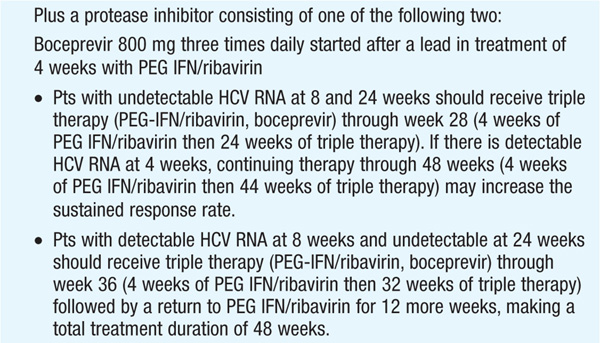

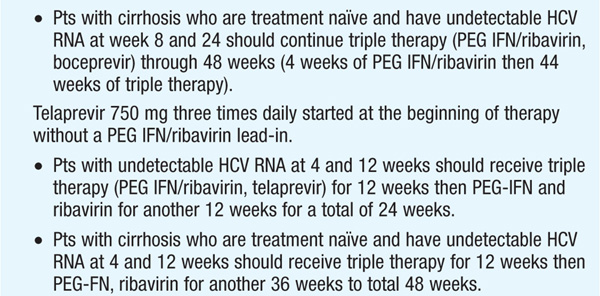

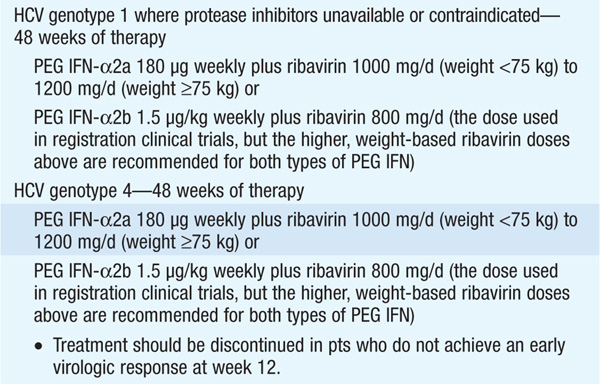

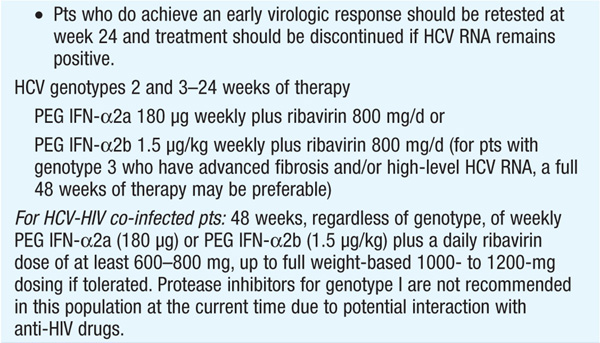

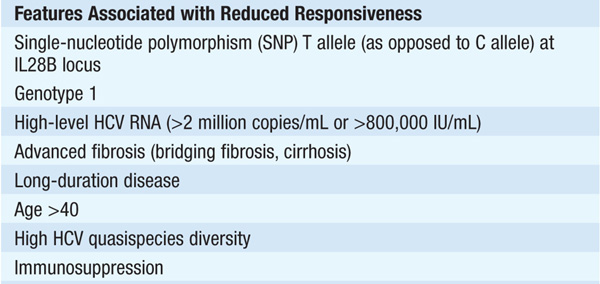

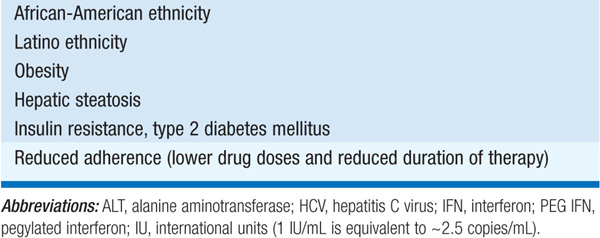

Therapy should be considered in pts with detectable HCV RNA in serum and biopsy evidence of at least moderate chronic hepatitis (portal or bridging fibrosis). The current agents used in the treatment of chronic HCV, as well as their dosage and duration, depend on HCV genotype (see Tables 164-3 and Table 164-4). For pts with genotype 1, PEG IFN/ribavirin should be combined with a protease inhibitor (boceprevir, telaprevir) where available. Protease inhibitors should never be used alone due to development of resistance. Since the presently available HCV protease inhibitors have not been studied on pts with genotypes other than I, their use in these populations is not recommended (see Table 164-3).

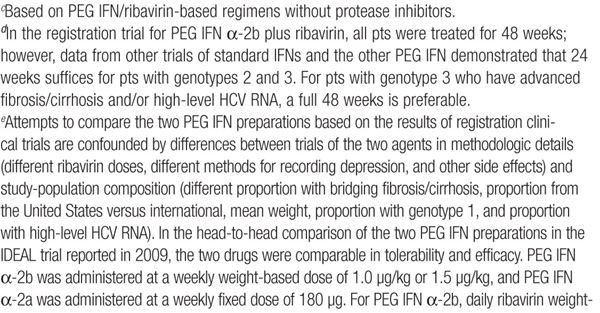

TABLE 164-3 PEGYLATED INTERFERON α-2A AND α-2B FOR CHRONIC HEPATITIS C

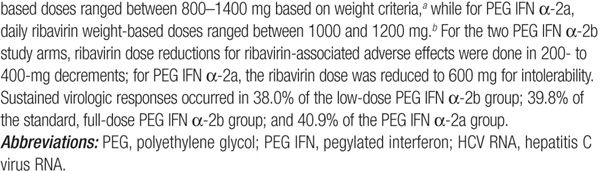

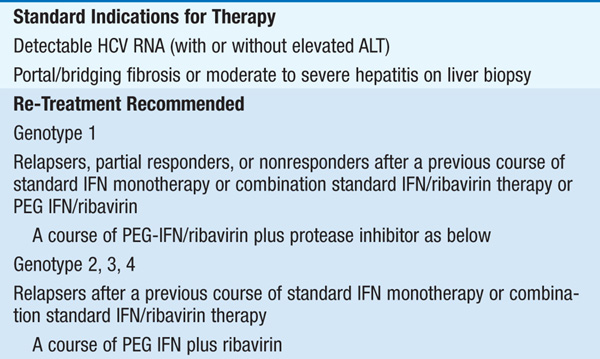

TABLE 164-4 INDICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ANTIVIRAL THERAPY OF CHRONIC HEPATITIS C

Monitoring of HCV plasma RNA is useful in assessing response to therapy. The goal of treatment is to eradicate HCV RNA, which is predicted by the absence of HCV RNA by polymerase chain reaction 6 months after stopping treatment (“sustained viral response”). The failure to achieve a 2-log drop in HCV RNA by week 12 of therapy (“early virologic response”) makes it unlikely that further therapy will result in a sustained virologic response. Thus, it is recommended that HCV RNA be measured at baseline and at weeks 4, 12, and 24 to assess response to treatment and to aid in decisions regarding treatment duration as well as after 12 weeks of therapy. Pts with genotype I receiving boceprevir should additionally have HCV RNA measured at week 8, as this may influence the duration of therapy. The current consensus view is that therapy can be stopped if an early virologic response is not achieved.

HEPATITIS A

Although hepatitis A rarely causes fulminant hepatic failure, it may do so more frequently in pts with chronic liver disease—especially those with chronic hepatitis B or C. The hepatitis A vaccine is immunogenic and well tolerated in pts with chronic hepatitis. Thus, pts with chronic liver disease, especially those with chronic hepatitis B or C, should be vaccinated against hepatitis A.

AUTOIMMUNE HEPATITIS

CLASSIFICATION

Type I: classic autoimmune hepatitis, anti–smooth-muscle and/or anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA). Type II: associated with anti-liver/kidney microsomal (anti-LKM) antibodies, which are directed against cytochrome P450IID6 (seen primarily in southern Europe). Type III pts lack ANA and anti-LKM, have antibodies reactive with hepatocyte cytokeratins; clinically similar to type I. Criteria have been suggested by an international group for establishing a diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Classic autoimmune hepatitis (type I): 80% women, third to fifth decades. Abrupt onset (acute hepatitis) in a third. Insidious onset in two-thirds: progressive jaundice, anorexia, hepatomegaly, abdominal pain, epistaxis, fever, fatigue, amenorrhea. Leads to cirrhosis; >50% 5-year mortality if untreated.

EXTRAHEPATIC MANIFESTATIONS

Rash, arthralgias, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, thyroiditis, hemolytic anemia, nephritis.

SEROLOGIC ABNORMALITIES

Hypergammaglobulinemia, positive rheumatoid factor, smooth-muscle antibody (40–80%), ANA (20–50%), antimitochondrial antibody (10–20%), false-positive anti-HCV enzyme immunoassay but usually not HCV RNA, atypical p-ANCA. Type II: anti-LKM antibody.

TREATMENT Autoimmune Hepatitis

Indicated for symptomatic disease with biopsy evidence of severe chronic hepatitis (bridging necrosis), marked aminotransferase elevations (5- to 10-fold), and hypergammaglobulinemia. Prednisone or prednisolone 30–60 mg/d PO tapered to 10–15 mg/d over several weeks; often azathioprine 50 mg/d PO is also administered to permit lower glucocorticoid doses and avoid steroid side effects. Monitor liver function tests monthly. Symptoms may improve rapidly, but biochemical improvement may take weeks or months and subsequent histologic improvement (to lesion of mild chronic hepatitis or normal biopsy) up to 18–24 months. Therapy should be continued for at least 12–18 months. Relapse occurs in at least 50% of cases (re-treat). For frequent relapses, consider maintenance therapy with low-dose glucocorticoids or azathioprine 2 (mg/kg)/d.

For a more detailed discussion, see Dienstag JL: Chronic Hepatitis, Chap. 306, p. 2567, in HPIM-18.