Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is the most common form of progressive motor neuron disease (Table 197-1). ALS is caused by degeneration of motor neurons at all levels of the CNS, including anterior horns of the spinal cord, brainstem motor nuclei, and motor cortex. Familial ALS (FALS) represents 5–10% of the total and is inherited usually as an autosomal dominant disorder.

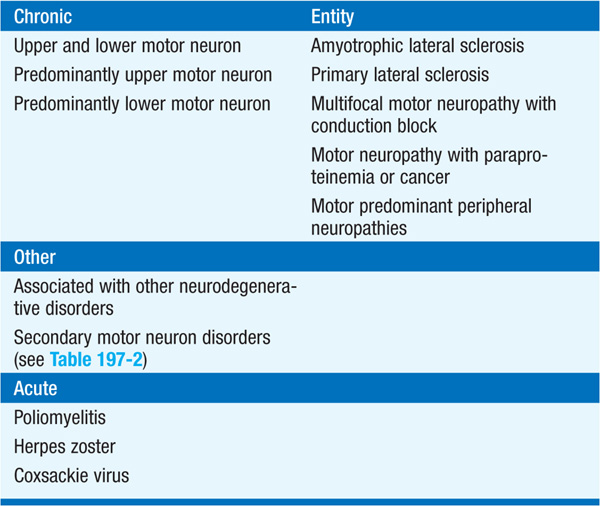

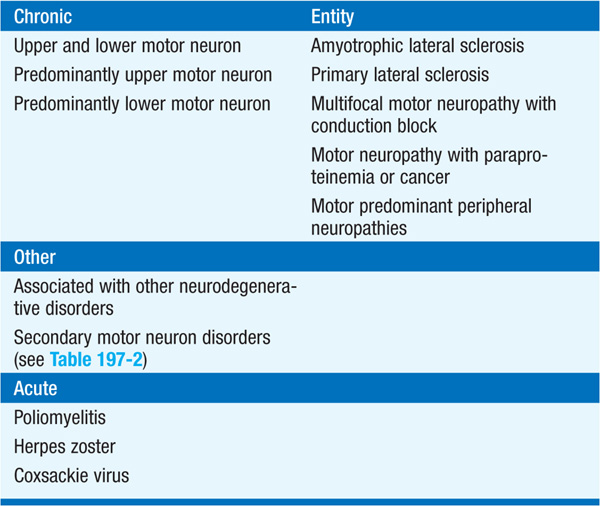

TABLE 197-1 SPORADIC MOTOR NEURON DISEASES

Onset is usually midlife, with most cases progressing to death in 3–5 years. In most societies there is an incidence of 1–3 per 100,000 and a prevalence of 3–5 per 100,000. Presentation is variable depending on whether upper motor or lower motor neurons are more prominently involved initially. Common initial symptoms are weakness, muscle wasting, stiffness and cramping, and twitching in muscles of hands and arms, often first in the intrinsic hand muscles. Legs are less severely involved than arms, with complaints of leg stiffness, cramping, and weakness common. Symptoms of brainstem involvement include dysphagia, which may lead to aspiration pneumonia and compromised energy intake; there may be prominent wasting of the tongue leading to difficulty in articulation (dysarthria), phonation, and deglutition. Weakness of ventilatory muscles leads to respiratory insufficiency. Additional features that characterize ALS are lack of sensory abnormalities, pseudobulbar palsy (e.g., involuntary laughter, crying), and absence of bowel or bladder dysfunction. Dementia is not a component of sporadic ALS; in some families ALS is co-inherited with frontotemporal dementia characterized by behavioral abnormalities due to frontal lobe dysfunction.

Pathologic hallmark is death of lower motor neurons (consisting of anterior horn cells in the spinal cord and their brainstem homologues innervating bulbar muscles) and upper, or corticospinal, motor neurons (originating in layer five of the motor cortex and descending via the pyramidal tract to synapse with lower motor neurons). Although at onset ALS may involve selective loss of function of only upper or lower motor neurons, it ultimately causes progressive loss of both; the absence of clear involvement of both motor neuron types should call into question the diagnosis of ALS.

EMG provides objective evidence of extensive muscle denervation not confined to the territory of individual peripheral nerves and nerve roots. CSF is usually normal. Muscle enzymes (e.g., CK) may be elevated.

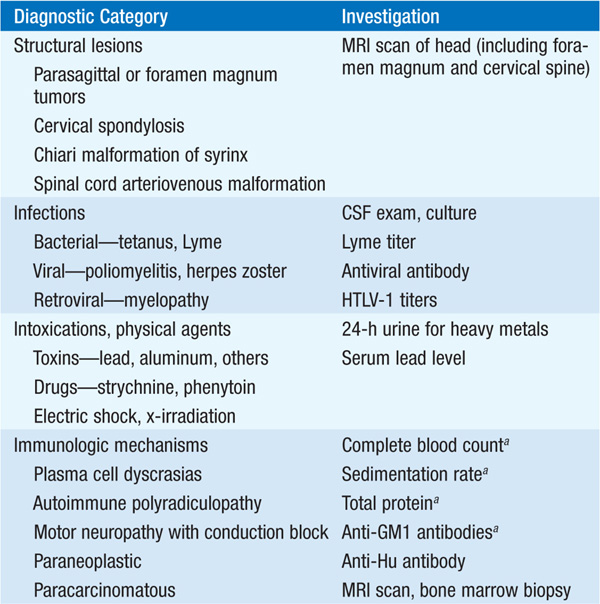

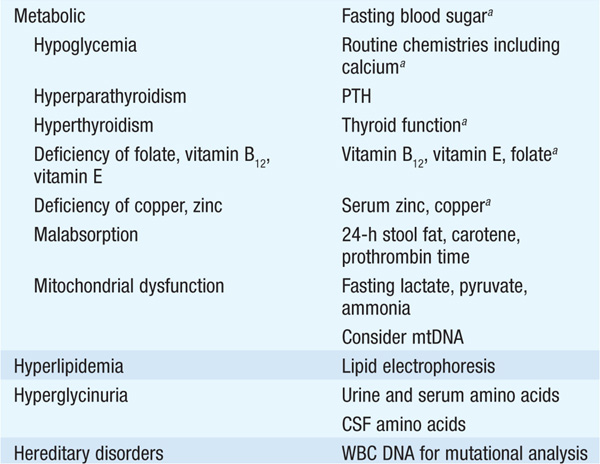

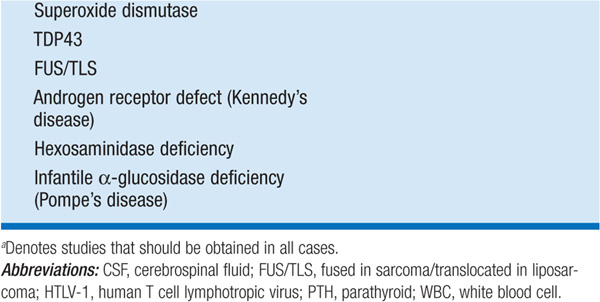

Several types of secondary motor neuron disorders that resemble ALS are treatable (Table 197-2); therefore all pts should have a careful search for these disorders.

TABLE 197-2 ETIOLOGY OF MOTOR NEURON DISORDERS

MRI or CT myelography is often required to exclude compressive lesions of the foramen magnum or cervical spine. When involvement is restricted to lower motor neurons only, another important entity is multi-focal motor neuropathy with conduction block (MMCB). A diffuse, lower motor axonal neuropathy mimicking ALS sometimes evolves in association with hematopoietic disorders such as lymphoma or multiple myeloma; an M-component in serum should prompt consideration of a bone marrow biopsy. Lyme disease may also cause an axonal, lower motor neuropathy, typically with intense proximal limb pain and a CSF pleocytosis. Other treatable disorders that occasionally mimic ALS are chronic lead poisoning and thyrotoxicosis.

Pulmonary function studies may aid in management of ventilation. Swallowing evaluation identifies those at risk for aspiration. Genetic testing is available for superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) (20% of FALS) and for rare mutations in other genes.

TREATMENT Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

• There is no treatment that arrests the underlying pathologic process in ALS.

• The drug riluzole produces modest lengthening of survival; in one trial the survival rate at 18 months with riluzole (100 mg/d) was similar to placebo at 15 months. It may act by diminishing glutamate release and thereby decreasing excitotoxic neuronal cell death. Side effects of riluzole include nausea, dizziness, weight loss, and elevation of liver enzymes.

• Multiple therapies are presently in clinical trials for ALS including ceftriaxone, pramipexole, and tamoxifen; interventions such as antisense oligonucleotides that diminish expression of mutant SOD1 protein are in trial for SOD1-mediated ALS.

• A variety of rehabilitative aids may substantially assist ALS pts. Foot-drop splints facilitate ambulation, and finger extension splints can potentiate grip.

• Respiratory support may be life-sustaining. For pts electing against long-term ventilation by tracheostomy, positive-pressure ventilation by mouth or nose provides transient (several weeks) relief from hypercarbia and hypoxia. Also beneficial are respiratory devices that produce an artificial cough; these help to clear airways and prevent aspiration pneumonia.

• When bulbar disease prevents normal chewing and swallowing, gastrostomy is helpful in restoring normal nutrition and hydration.

• Speech synthesizers can augment speech when there is advanced bulbar palsy.

• Web-based information on ALS is offered by the Muscular Dystrophy Association (www.mdausa.org) and the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association (www.alsa.org).

For a more detailed discussion, see Brown RH Jr: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Motor Neuron Diseases, Chap. 374, p. 3345, in HPIM-18.