104 Gallery of the Palais Royal, full of stalls selling every kind of finery. Engraving by Abraham Bosse, c. 1640.

We have seen that during the second half of the sixteenth century Spain set the dominant tone in fashion. This influence persisted into the 1600s, but with modifications, notably the abandonment of stuffed and busked ‘peascod’ doublets and the widening of sleeves. Ruffs, too, became smaller in France and England, but continued to grow even larger in the Netherlands.

The doublet had a short skirt consisting of a number of overlapping tabs. From about 1610 these tabs were longer and curved down in front to a sharp point. The garment was provided with a high-standing collar buttoning in front, but generally concealed by the ruff. This was carried over from the preceding century but with certain variations, being sometimes in double or treble layers of tubular pleats starched by means of ‘setting sticks’. Ruffs were usually white but sometimes yellow. The invention of starch, denounced by Puritan moralists as a new vanity, allowed the ruff to dispense with the wire frame or ‘underpropper’ which had previously been necessary.

In France, Henry IV, in contrast to Henry III, was a man of simple tastes. He was by no means a prude, being famous as le VertGalant for his amours; but he had no liking for extravagance in dress, and issued several sumptuary laws, largely aimed at preventing the import of expensive materials of foreign manufacture. This had most effect on the dress of the bourgeoisie, members of which began to wear clothes made of wool. The courtiers continued to wear silk, but with fewer trimmings of gold and silver thread.

Women’s clothes, although still elaborate, were more natural, in that the female body was not so much deformed as it had been by tight-lacing and the cumbrous farthingale. Women benefited, too, by the transition from the ruff to the falling collar, and this tendency was even more apparent after the assassination of Henry IV and the accession of Louis XIII.

104 Gallery of the Palais Royal, full of stalls selling every kind of finery. Engraving by Abraham Bosse, c. 1640.

Fortunately we have a valuable documentation of the costume of this period in the engravings of Abraham Bosse.[105–8] Scholars are agreed that they are not fanciful but give a faithful picture of the modes and manners of the time. From these engravings and from the etchings of Jacques Callot we can gain a very clear idea of the costume which in France is associated with The Three Musketeers and in England was the dress of the ‘Cavaliers’. There was about it an element of martial swagger, with its breeches and doublet, its short cloak hanging from one shoulder, its wide-brimmed hat adorned with a plume and, above all, its boots. These could be of various forms, but the most characteristic style was that of the so-called ‘funnel boots’, with wide turnovers sometimes trimmed with lace. These were really riding boots, but from about 1610 they were frequently worn in town and indoors.

105–8 French noblemen and noblewoman, Abraham Bosse, c. 1629–36. All the men have the characteristic ‘bucket-top’ boots of the period.

When shoes were worn, they were decorated with enormous rosettes, made of ribbons, lace and spangles and often extremely costly. Women’s shoes were simpler, being almost completely concealed by the long skirt. In wet weather chopines were worn. These were wooden clogs covered with leather, worn under the shoes and sometimes with soles thick enough to qualify as stilts. They had been known since the beginning of the century (and in Venice from a much earlier date), as we can gather from Hamlet’s remark: ‘Your ladyship is nearer heaven than when I saw you last, by the altitude of a chopine’.

Women’s dress consisted of the bodice, the petticoat and the gown. The bodice was sometimes extravagantly décolleté and laced with a silk ribbon in front. The lacing was often covered with a ‘piece’ or ‘plastron’. The sleeves were large, slashed or paned, and puffed out with stuffing. The characteristic skirt of the period was in fact two skirts, the over-skirt being gathered up to reveal the skirt underneath. The falling collar became ever more elaborate, with a border of costly lace.

Hair was generally worn rather flat on the top of the head, but frizzed out at the sides in thick curls. Women in general did not wear hats, but out of doors they provided themselves with little hoods of black taffeta or else wore a simple lace fichu on their heads.

What we have been describing were in effect French modes. In England they were copied, as we have noted, by the Cavaliers. The Puritans, on the other hand, tended to derive their fashions (if such a frivolous word may be allowed in this connection) from Holland.

The system of government of the Protestant Netherlands was different from that obtaining elsewhere in Europe. Holland was ruled by a prosperous bourgeoisie, a body of influential and pious merchants and magistrates known as ‘regents’. They wore a distinctive costume of conservative cut and black in hue. There is a paradox in this, for the Dutch had fought bitterly to obtain their freedom from Spain, and yet the formality and sobriety of their costume continued to show a Spanish influence. Indeed, it seemed to them suitable raiment for their own austere brand of Protestantism. But the most striking thing about Dutch costume in the first half of the seventeenth century is the persistence of the ruff.[113] It not only persisted; it grew larger and larger until it became a literal cartwheel of elaborately goffered linen folds, as can be seen in the portraits of Frans Hals. The English Puritans never copied this fashion. Many Dutchmen, however, wore their hair short, and this became the characteristic of the Parliament men in England: hence the nickname ‘Roundheads’.

We gain a charming glimpse of English fashions in the middle of the century from the engravings of Wenceslas Hollar. Women wore their hair flat on the top of the head, with side curls or ringlets. The bodice was cut low, but with a linen kerchief or collar, which was sometimes transparent.[112] The three-quarter-length sleeves had turn-ups of lace. The bodice came to a deep point and was laced down the front with visible ribbons. The skirt fell in folds to the ground. The general effect might be described as a stylish modesty.

109 Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland, studio of Daniel Mytens, 1640. The new passion for lace, worn at the sitter’s throat and, more inventively, in the tops of his boots.

110 Wedding celebration, Wolfgang Heimbren, 1637.

But the strange and, according to the moralists, immodest fashion had already arrived of wearing patches on the face. The satirist John Bulwer in his Artificial Changeling, published in 1653, ridicules the ladies’ ‘vain custom of spotting their faces out of an affectation of a mole, to set off their beauty, such as Venus had; and it is well if one patch will serve to make their faces remarkable, for some fill their visages full of them, varied into all manner of shapes’. Such shapes might be stars, crescents or even a coach and horses, cut out of black ‘court plaster’. This strange fashion lasted for more than fifty years.

The Restoration of Charles II in 1660 brought with it the triumph of French modes, although significant differences continued to exist between the clothes worn in France and those worn in England. The fashions which Charles brought with him and which were adopted by his court were among the strangest male garments ever worn. Subsequent historians have regarded them with an unfavourable eye. ‘Taste and elegance’, says F. W. Fairholt, ‘were abandoned for extravagance and folly; and the male costume, which in the time of Charles I had reached the highest point of picturesque splendour, degenerated and declined from this moment’ (Costume in England, 1885).

Randle Holme, writing in 1684, described men’s clothes as consisting of ‘short-waisted doublets and petticoat breeches, the lining lower than the breeches, tied above the knee, ribbons up to pocket-holes half the length of the breeches, then ribbons all about the waistband, the shirt hanging out’ (Accidents of Armoury). The petticoat breeches were a French fashion, or rather had become French, having been introduced by a certain Comte de Salm, known as ‘the Rhinegrave’. The breeches were therefore called ‘Rhinegraves’ and were first worn in England, two years before the Restoration, by William Ravenscroft. They were then regarded as something of a curiosity, but after 1660 they became for a time universal among men with any pretension to fashion. They were so wide that, as Samuel Pepys tells us in an entry in his Diary for 1661, it was possible to put both legs into one compartment.

111 Doublet and trunk hose of silk and silver tissue, joined by hook and eye fastenings, worn by the 6th Duke of Lennox: English, c. 1665.

112 Autumn, Wenceslas Hollar, 1642.

113 Portrait of a woman, Frans Hals, c. 1635.

The extremely short doublet, so short that it showed a gap of shirt between its lower edge and the top of the breeches, was now buttoned down the front and resembled a sleeved waistcoat. There was a mania for bunches of ribbon, worn not only on the breeches but on the shoulders and elsewhere. We hear of a suit and cloak of satin, trimmed with thirty-six yards of silver ribbon, and no less than 250 yards of ribbon in bunches were used on one pair of petticoat breeches. The general effect of men’s clothes at this period was of a fantastic negligence, well suited to the moral climate of the Restoration court.

Women’s clothes were equally loose and apparently careless, so that most of the court beauties painted by Lely seem to have been caught, as it were, in négligé, although some allowance must no doubt be made for the painter’s poetic fancy.[114] The style had its own attractiveness and even the sober Planché is moved to enthusiasm. ‘A studied negligence,’ he says, ‘an elegant déshabille, is the prevailing character of the costume in which they are nearly all represented; their glossy ringlets escaping from a simple bandeau of pearls or adorned by a single rose, fall in graceful profusion upon many necks unveiled by even the transparent lawn of the band or the partlet; and the fair round arm, bare to the elbow, reclines upon the voluptuous satin petticoat while the gown of the same rich material piles up its voluminous train in the background’ (A Cyclopaedia of Costume, vol. II 1879, pl. 242).

114 Mary Capel (1630–1715), Later Duchess of Beaufort, and Her Sister Elizabeth (1633–1678), Countess of Carnarvon, Peter Lely, c. 1660.

There was not much change in female dress during the greater part of Charles II’s reign. The long pointed waists continued and gradually became tighter. The tucked-up skirts, known, confusingly, as manteaux, grew more formal in appearance, the general outline of the figure stiffer and narrower. The large collars of lace went out of fashion in the early 1670s, although, out of doors, a kerchief called a ‘palatine’ covered the bare shoulders. But while women’s clothes remained comparatively static, those worn by men underwent a real revolution, the ultimate consequences of which can still be seen in modern dress.

It is strange that the name of Charles II, of all people, should be associated with a ‘reform’ of dress. Perhaps he was sobered for a moment by the plague and fire that had just devastated his capital, but, at all events, within little more than a month of the extinguishing of the fire, he took the step which provoked so much comment in contemporary diaries and memoirs. ‘In this month’, we read in Rugge’s Diurnal for 11 October 1666, ‘his Magestie and whole Court changed the fashion of their clothes, viz., a close coat of cloth pinkt, with a white taffety under the cutts. This in length reached the calf of the leg, and upon that a surcoat cutt at the breast which hung loose and shorter than the vest six inches. The breeches, the Spanish cut, and buskins some of cloth, some of leather, but of the same colour as the vest or garment.’

115 Charles II, Pieter Stevens, c. 1670. The King is in the new fashion with lace rabat, full-bottomed wig and plumed hat anticipating the tricorne.

Pepys, too, describes the new dress and is even more precise in his dates. On 8 October 1666 he notes in his Diary: ‘The King hath yesterday in Council declared his resolution of setting a fashion of clothes which he will never alter.’ On 15 October he comments: ‘This day the King begins to put on his vest, and I did see several persons of the House of Lords and Commons too, great courtiers, who are in it; being a long cassocke close to the body, of black cloth, and pinked with white silke under it, and a coat over it, and the legs ruffled with black riband like a pigeon’s leg; and, upon the whole, I wish the King may keep it, for it is a very fine and handsome garment.’

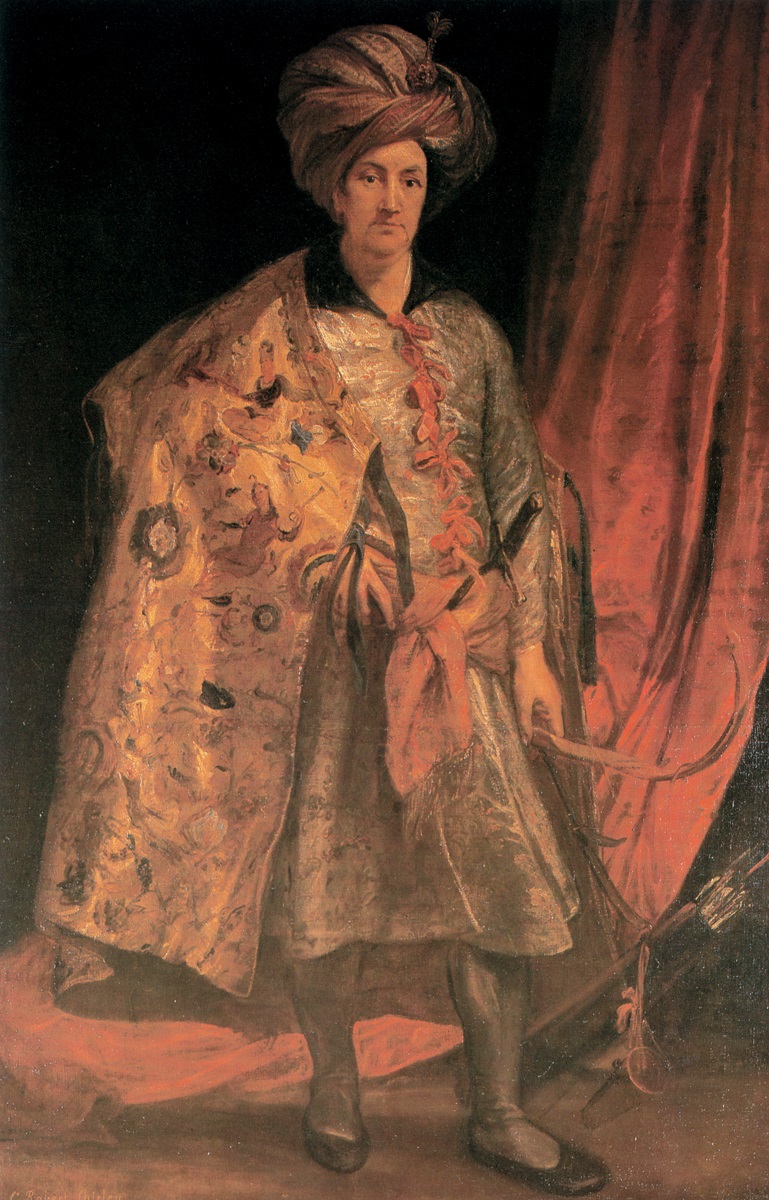

Evelyn’s Diary is equally explicit. Under the date 18 October, he remarks: ‘To Court, it being the first time his Majesty put himself solemnly into the Eastern fashion of vest, changing doublet, stiff collar, bands and cloak, into a comely dress after the Persian mode, with girdles or straps, and shoestrings and garters into buckles, of which some were set with precious stones, resolving never to alter it, and to leave the French mode, which had hitherto obtained to our great expense and reproach. Upon which divers courtiers and gentlemen gave his Majesty gold by way of wager that he would not persist in this resolution.’

Charles, however, did persist – but he made certain modifications. Pepys notes (17 October 1666) that ‘the Court is full of vests, only my Lord St Albans not pinked but plain black; and they say the King says the pinking upon white makes them look too much like magpies, and therefore hath bespoke one of plain velvet.’ Evelyn described the new garment as a ‘dress after the Persian mode’, and as ‘the Eastern fashion of vest’. Other contemporary references call the new fashion ‘Turkish’; and one has to admit that it does bear a certain resemblance to the Persian coat except that the latter had long sleeves, whereas the sleeves of Charles’s ‘vest’ were extremely short, the white shirt sleeve ballooning out below it.

Curiously enough the Persian coat was not entirely unknown at the English court, Sir Robert Shirley having regularly worn it as long before as the reign of Charles I.[116] Shirley, who had travelled much in Persia in the early years of the seventeenth century, occupied the strange position, for an Englishman, of Persian Ambassador at the court of St James’s. English relations with Persia were, indeed, very close throughout the century; and a new fillip to English interest in the East was given when Charles II received the island of Bombay as part of the dowry of Catherine of Braganza.

The English King’s action was looked upon as a deliberate attempt to break away from French fashions, a step that was hardly likely to please Louis XIV, who was then endeavouring, with considerable success, to make France the arbiter of Europe, not only politically but also in matters of taste. Pepys notes (22 November 1666) that ‘the King of France hath, in defiance to the King of England, caused all his footmen to be put into vests, and that the noblemen of France will do the like; which, if true, is the greatest indignity ever done by one prince to another’. French scholars, however, have pointed out that a very similar garment was introduced at the French court as early as 1662. It was at first worn only by a few privileged countiers, but by 1670 its use had become universal.

How did it come about that this Persian mode became the ancestor of modern costume? Richard Heath notes that ‘over the vest a loose overcoat was worn; but, since all reference to it is omitted by Evelyn, and Pepys speaks of seeing the Court full of vests, it was evidently only intended for outdoor wear’ (‘Studies in English Costume I’, Magazine of Art, vol. XI, 1887–88). It can be seen, worn as an overcoat, in a contemporary engraving of the funeral of General Monck in 1670. In the end the overcoat became the coat, and the vest became what was later, when it had grown much shorter, to be called the waistcoat. It is interesting to note that London bespoke tailors still refer to a waistcoat as a ‘vest’.

At first it was extremely long, almost as long as the coat, coming nearly to the knees and buttoned all the way down, almost completely concealing the breeches.[117] The coat was rather plain, embroidery being reserved for the inner garment, and the wide falling collar disappeared, since the coat made it inconvenient. Instead a cravat of lace or muslin was worn.

There has been considerable controversy about the origin of this item of apparel. The name seems to imply that it was derived from the neckwear of the Croats in the French service and that it was copied first by the French officers and then by the courtiers of Louis XIV. A fine-lace industry had been established in France by the enlightened minister Colbert, and the King, anxious to encourage it, wore its products himself and decreed that nothing but point de France should be worn at court. The well-known expert on old lace, Mrs Nevill Jackson, writing in The Connoisseur, remarks that ‘the neckwear of a gentleman of fashion which immediately preceded the cravat was the rabat or falling collar, which in its turn had ousted the ruff, so that we are not surprised to find that the earliest cravats hang like the fronts of a turn-down collar, and are guiltless of bow or knot’.

116 Sir Robert Shirley, Anthony van Dyck, 1622. Anticipation of the fashionable clothes of half a century later.

117 Portrait of Louis, Dauphin de France, Henry Bonnart, 1694. The full-bottomed wig is now universal in polite society.

Point de France, and the even more elaborate point de Venise, was extremely costly. We learn from the Great Wardrobe Accounts that Charles II paid £20. 12s. 0d. for a new cravat, and James II paid £30. 10s. 0d. for one to be worn at his own Coronation. These were very considerable sums in those days.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century the cravat had become narrower and longer. A bow of ribbon was sometimes worn behind it, and the cravat itself (no longer made of lace but of muslin or cambric) was sometimes knotted. At the Battle of Steinkirk in 1692 the French officers, summoned to repel a surprise attack, had no time to arrange their cravats properly. They accordingly twisted them quickly, drawing them through a buttonhole to keep them out of the way. This was the origin of the ‘steinkirk’ which became a prevalent mode for about a dozen years not only in France but all over Europe.

118 Mode bourgeoise, N. Guérard, c. 1690. The dress is remarkable for the profusion of lace with which it is trimmed. The high fontange is also of lace. The skirt is lifted to display the silk stockings.

119 Lady of Quality, J. D. de Saint-Jean, 1693.

120 Lady of Quality, en déshabille, J. D. de Saint-Jean, 1687.

We have noted that the old style of falling collar was inconvenient to wear with the new kind of ‘vest’. It therefore shrank to a rabat; but another reason for its diminution in size was that the greater part of a falling collar would have been invisible anyway owing to the custom of wearing a periwig. In the preceding reign the prevailing fashion for long hair no doubt caused many gentlemen to provide themselves with postiches, but the effect aimed at was that of natural hair. By 1660, however, the periwig had become frankly artificial and it was adopted with such enthusiasm that no less than two hundred perruquiers were employed at the French Court.

The English court took a little time to catch up, but by November 1663 Pepys was able to note in his Diary: ‘I heard the Duke [of York] say that he was going to wear a periwig and they say the King also will. I never till this day observed that the King is mighty gray.’ And in the entry for 15 February 1664 he remarks: ‘To White Hall, to the Duke; where he first put on a periwig today: but methought his hair cut short in order thereto did look very pretty of itself, before he put on his periwig.’ It was of course necessary to cut the hair close to the scalp, or even to shave it, to make the periwig fit.

In April 1664 he went to Hyde Park and ‘saw the King with his periwig’. Pepys had already decided to adopt the new fashion, and one can’t help feeling that he was a little disappointed at not making more of a sensation by wearing it when he went to church in it for the first time: ‘I found that my coming in a periwig did not prove so strange as I was afraid it would for I thought that all the church would presently have set their eyes upon me.’ The invaluable diarist tells us that in 1667 he paid £4. 10s. 0d. for two periwigs, and that a year later he arranged with his barber to keep his periwigs in good order for 20s. per annum. But of course the periwigs worn by the courtiers were much more expensive.

121, 122 Middle- and working-class costume, S. le Clerc, end of seventeenth century.

The full-bottomed wig worn by men of fashion was extremely large and heavy, and active persons such as soldiers soon found it an encumbrance. We hear of a ‘campaign’ wig and a ‘travelling’ wig. The strange thing is that a wig of some kind was considered absolutely essential and that the fashion should have lasted, for the upper classes of Western Europe, for nearly a century.

Even more curious than the wearing of mountains of artificial hair was the use of powder. This certainly did not originate with Louis XIV, who disapproved of it and only adopted it when it had become a universal fashion at the end of his reign. The periwig of Charles II was black and remained so, and, from their portraits, it seems unlikely that either William III or Queen Anne ever wore powder. Indeed, powder does not come into general use until the 1690s. Pepys, whose Diary stops too soon, does not mention it at all. Evelyn, however, speaks of it in his Mundus Muliebris, published in 1694, but in this he was, of course, satirizing female fashions. The most definite evidence of the use of hair-powder by Englishmen is to be obtained from the dramatists of the period. Colley Cibber, in his famous comedy Love’s Last Shift (1695), speaks of ‘a cloud of powder beaten out of a beau’s periwig’.

123, 124 Aristocratic costumes, S. le Clerc, end of seventeenth century.

Women did not wear the periwig, but they aspired to the same lofty heights in their headdress by the invention of the fontange, so characteristic of the 1690s.[118] It was named after one of the favourites of Louis XIV who, the story goes, finding her hair disarranged while hunting, tied it up hastily with one of her garters. The King expressed his admiration, and the mode was launched. Next day all the Court ladies appeared with their hair tied with a ribbon with the bow in front. The fashion quickly crossed the Channel and is one of the earliest examples of a French mode imposing itself on England, universally and almost at once.

Soon a simple bow of ribbon was not enough. Lace was added, and then a cap was added to the lace, with a wire frame to support the ever increasing height of the structure. It was then called, perhaps in irony, a ‘commode’, and in England was known also as a ‘tower’. In the Ladies Dictionary of 1694 it is described as ‘a frame of wire two or three stories high, fitted to the head, and covered with tiffany or other thin silks being now compleated into the whole headdress’. Moralists, as usual, regarded the new fashion with grave misgiving, as an incitement to pride, and Samuel Wesley the Elder, father of the more famous John Wesley, once preached a sermon against it, from the text: ‘Let him that is upon the house-top not come down’, drawing particular attention to the words ‘Top-knot, come down.’

Various accounts are given of the derivation of the fashion and of the reasons for its disappearance. Louis XIV had grown tired of it by 1699 and expressed his disapproval, but it was the appearance at court of an Englishwoman, Lady Sandwich, ‘avec une petite coiffure basse’, which really changed the mode. This must have been a personal eccentricity on the part of Lady Sandwich, for in general French fashions were dropped in England some time after they had been abandoned in France. We find the Mercure Galant for November 1699 remarking that the old style of high coiffure was beginning to appear ridiculous. Some ten years later Addison was commenting upon its final disappearance in England.

125 Portrait of the Children of James II of England, Largillière, 1695.

126, 127 Two men dressed in French fashion, Jean Mariette, c. 1696.

The male hat assumed, in the closing years of the seventeenth century, the shape it was to keep throughout the eighteenth. The hat of the Commonwealth, whether worn by Roundhead or by Cavalier (the latter wore it with a feather), was distinguished by its high crown and wide brim. Charles II brought in the so-called ‘French hat’, with wide brim and shallower crown, adorned with even more feathers than before. At the funeral of General Monck in 1670, already referred to, the hats are very small in brim also. Finally the crown settled down to a moderate height, and the brim, which had become wide again, underwent the process known as ‘cocking’ – that is to say, one portion of it was turned up either at the front, at the back or on one side of the head.

At first this seems to have been a matter of individual fancy: we hear, for instance, of the ‘Monmouth cock’. In the reign of William and Mary the hat began to be turned up in three places, thus forming the ‘three-cornered hat’ which lasted for a century and was accepted as the only possible headgear for gentlemen throughout the civilized world. ‘The cocked hat’, says Planché (Cyclopaedia, vol. I, 1876, p. 260), ‘was considered as a mark of gentility, professional rank, and distinction from the lower orders who wore them uncocked.’ Such differences as there were depended upon the width of the brim, the largest being known as the ‘Kevenhuller’.

Hats, strangely enough, were worn indoors and even at dinner; it was only in the presence of Royalty that gentlemen went bare-headed. The hat and the periwig were symbolic of the extreme formality of manners that marked the closing years of the seventeenth century.

128 Madame de Pompadour, François Boucher, 1759.