222 The Wertheimer Sisters, John Singer Sargent, c. 1901.

The period from the beginning of the century to the outbreak of World War I is usually spoken of in England as the Edwardian era, although the King actually died in 1910. In France, with a slight extension backwards into the middle of the 1890s, it was referred to as la belle époque. In both countries the atmosphere was very similar. It was an age of great ostentation and extravagance. In England, society and the court, which had of course always overlapped, now began to coincide and the King himself set the example. As Virginia Cowles remarks, ‘The fact that the King liked City men, millionaires…and American heiresses and pretty women (regardless of their origin) meant that the doors were open to anyone who succeeded in titillating the Monarch’s fancy.…Edwardian society modelled itself to suit the King’s personal demands. Everything was larger than lifesize. There was an avalanche of balls and dinners and country house parties. More money was spent on clothes, more food was consumed, more horses were raced, more infidelities were committed, more birds were shot, more yachts were commissioned, more late hours were kept, than ever before’ (Edward VII and His Circle, London 1956).

Fashion as always reflected the age. Like the King himself it favoured the mature woman, cool and commanding with a rather heavy bust, the effect of which was further emphasized by the so-called ‘health’ corsets which, in a laudable effort to prevent a downward pressure on the abdomen, made the body rigidly straight in front by throwing forward the bust and throwing back the hips. This produced the peculiar S-shaped stance so characteristic of the period. The skirt, smooth over the hips, flared out towards the ground in the shape of a bell. Cascades of lace descended from the corsage; indeed there was a passion for lace in every part of the gown. For those who could not afford real lace there was a considerable vogue for Irish crochet. The hair was built high on the head, and the flat pancake hat projected forward as if to balance the train. In the evening the dresses were extravagantly décolleté, but in the daytime the whole body was concealed from the ears to the feet. The little lace collar was kept in place by boning, and the arms were always completely concealed by long gloves. There was a rage for feathers, hats being adorned with one or more plumes; feather boas were worn round the neck. The best examples were made entirely of ostrich plumes and sometimes cost as much as ten guineas.

222 The Wertheimer Sisters, John Singer Sargent, c. 1901.

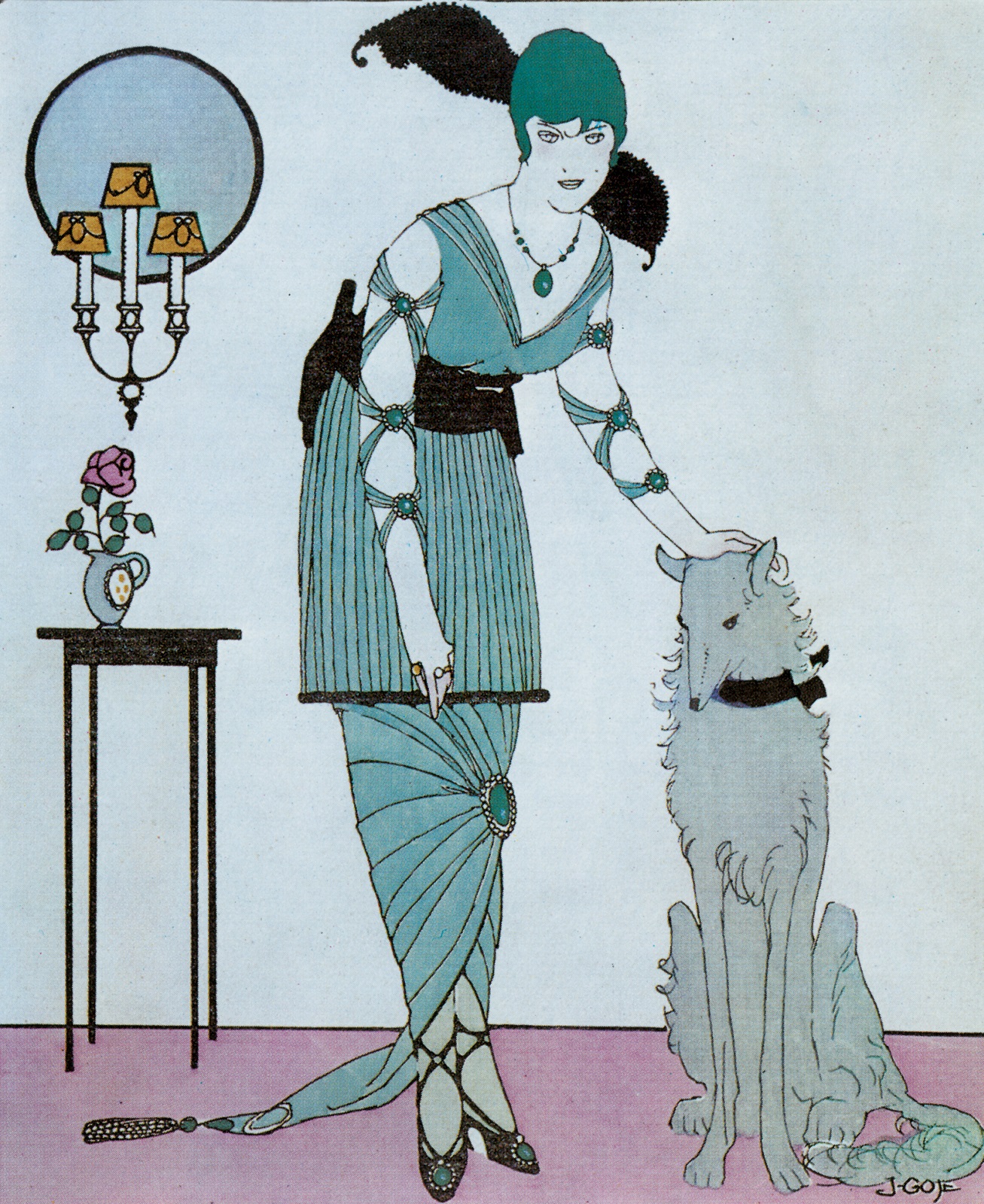

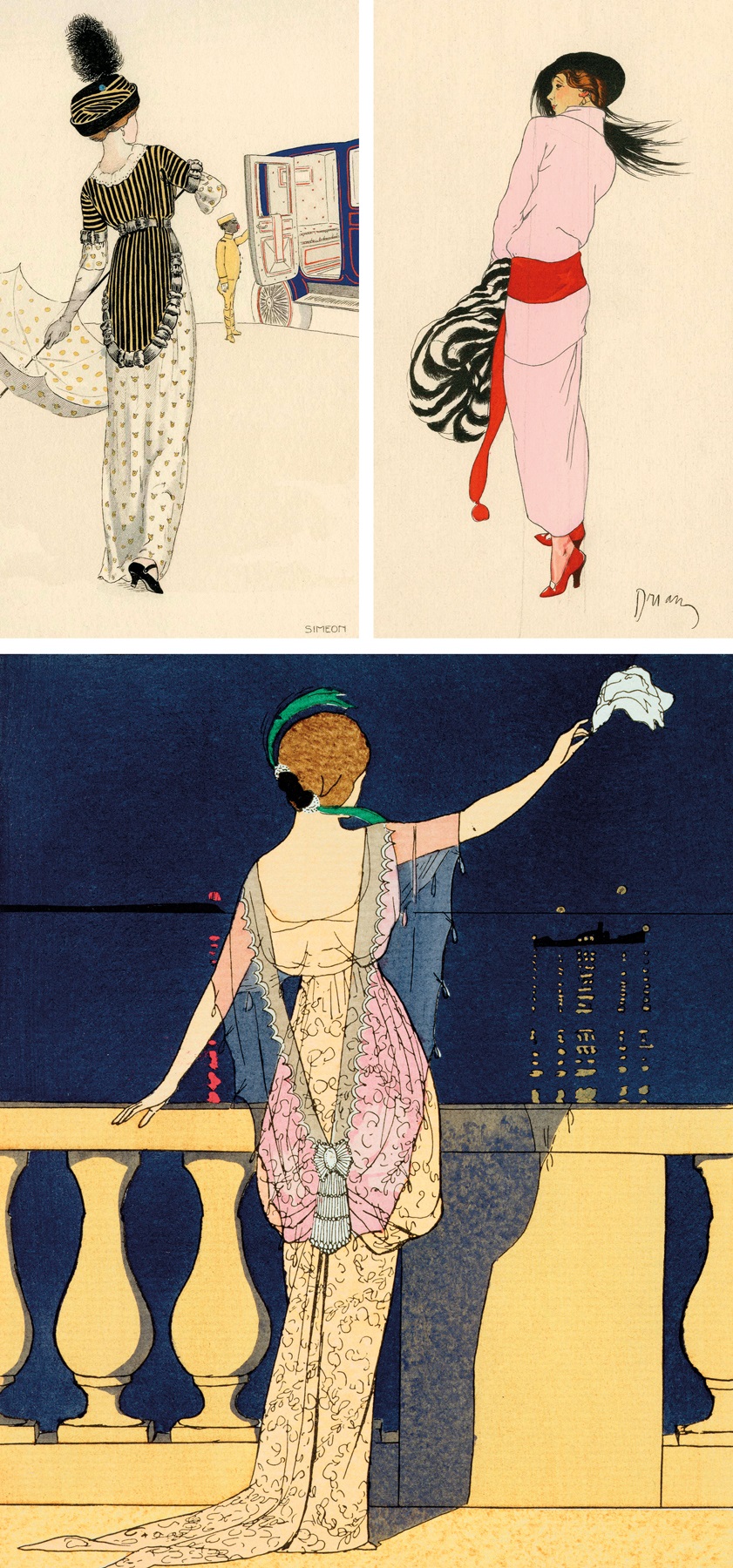

223 Evening dress: Il a-été primé. Fashion plate from the Gazette du Bon Ton, 1914.

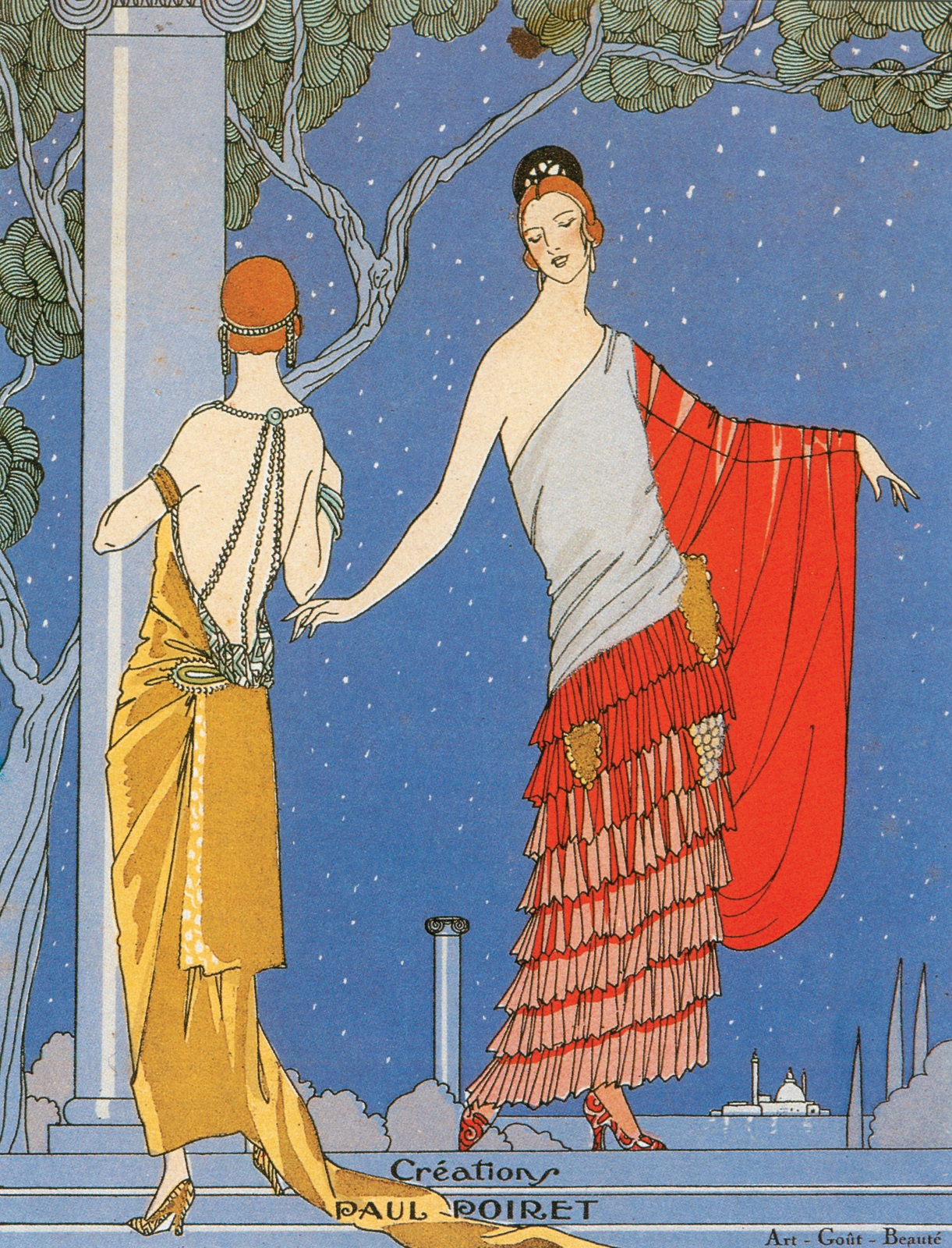

224 Evening gowns by Paul Poiret. Cover of Art-Goût-Beauté, March 1923.

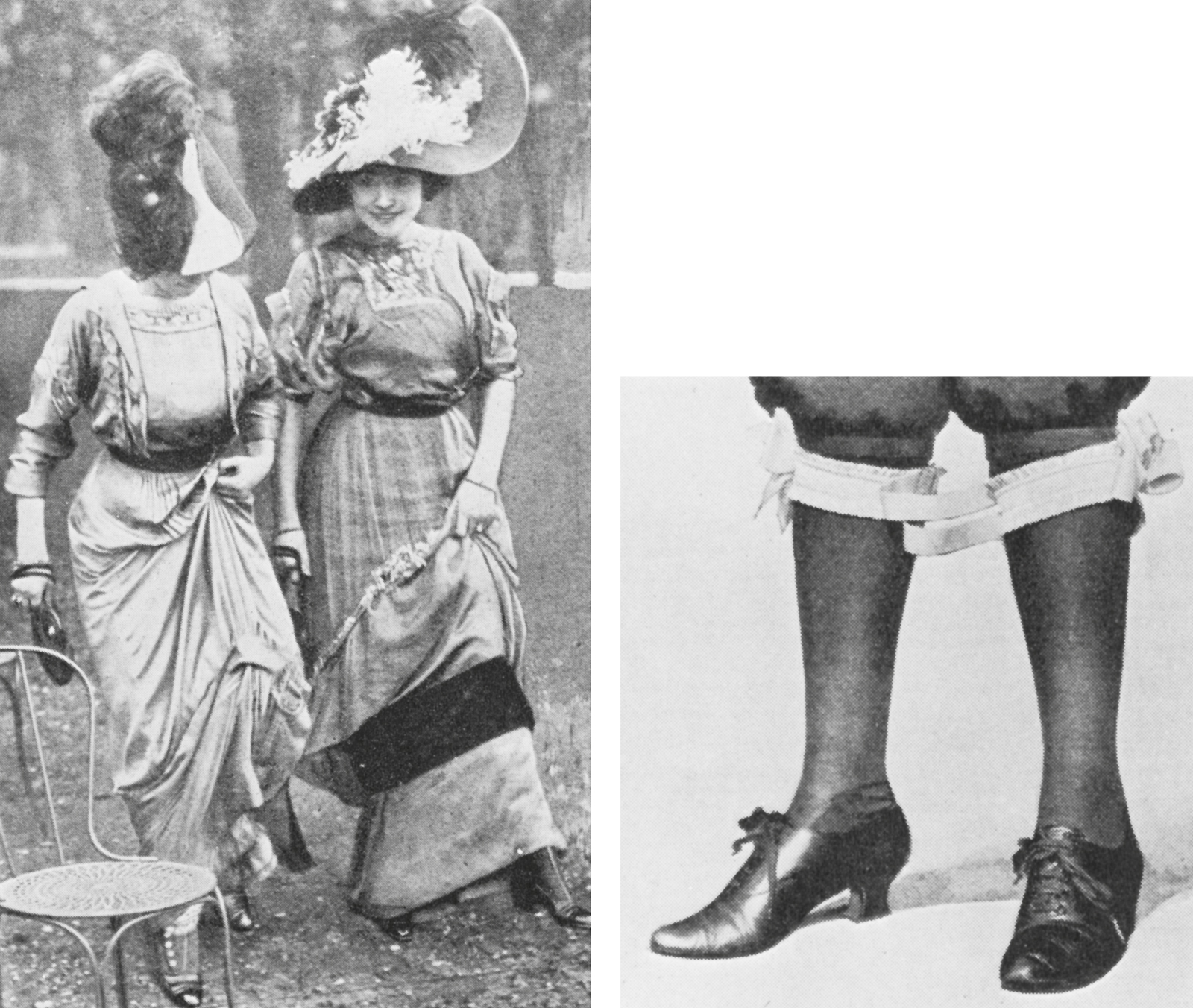

225, 226 Summer dresses trimmed with silk braid and with lace, May 1901.

227, 228 Evening dresses, 1901.

229 Straight-fronted corset, 1900.

One sometimes wonders if the climate of Europe was very much better in the early years of the century than it has been since: so many of the clothes of the period look as if they had been designed for a garden party or to be worn at a Riviera casino. In the winter the greater part of smart society seems to have swarmed over to Monte Carlo and similar Mediterranean resorts. Whatever the ups and downs of the entente in political circles, it was plain that the English upper classes, once more following the example of the King, regarded France and England as parts of the same civilization, stamping grounds for the same round of pleasure. The period has been defined as ‘the last good time of the upper classes’, and even the colours of clothes reflected the sunny optimism of those that had money to spend. It was all pastel shades of pink, pale blue or mauve, or black with small sequins sewn all over it. The favourite materials were crêpe de chine, chiffon, mousseline de soie and tulle. Many satin dresses were embroidered in floral patterns with little clusters of ribbon, or even painted by hand. The amount of sheer labour which went into the making of one fashionable gown was truly prodigious; one would have to go back to the embroidered brocades of the early eighteenth century to find anything comparable.

230 Summer dress, c. 1903.

231 Silk evening dress, 1911.

232 Evening dress with lace, 1907–8.

233 Dress of 1908. The period of the ‘Gibson Girl’, with heavy bust and swirling skirt, created by the artist Charles Dana Gibson. She was based on the beautiful Langhorne sisters, one of whom Gibson married.

234 Woman wearing a trotteur dress, 1907.

235 Woman wearing a brown Cheviot wool dress, pleated skirt and short jacket, 1907.

The blouse had now become an extremely elaborate confection. It was adorned with tucking and insertion. ‘Some blouses’, says a writer in a contemporary fashion magazine, ‘have circular trimmings of fluted muslin, giving a pretty graceful curve, and the trimming has a very fussy look.’ The bolero was extremely popular, as was also the so-called Eton bodice, a garment like a boy’s Eton jacket. The balloon sleeves of the 1890s had now been completely abandoned, sleeves in general being tight at the wrist and rather long so as to extend half over the hand. The tea gown, once merely a means of ‘getting into something loose’, was now an artistic creation in its own right.

Another feature of this period, however, is the importance of tailor-mades. A considerable number of young women of the middle classes were now beginning to earn their living as governesses, typists and shop assistants, and it would have been impossible for them to pursue their occupations in the elaborate garden-party dresses we have been describing. Even rich women wore tailor-mades in the country or when travelling, and the English tailors, rightly reputed to be the best in the world, reaped a rich harvest.

236 Walking dress, 1910.

237 Lady’s motoring costume, April 1905. In the open motor-cars of the period it was necessary to be protected from cold and, above all, from dust.

For men the accepted wear for all formal occasions was still the top hat and the frock coat, but the lounge suit worn with a homburg hat (a name derived from the German spa, much visited by the Prince of Wales) was increasingly to be seen, even in the West End of London. Straw hats were extremely popular and were sometimes worn even with riding breeches; trousers tended to be rather short and very narrow, and young men were beginning to wear them with permanent turn-ups and with a sharp crease in front, which had become possible since the mid-1890s with the invention of the trouser-press. Collars of white starched linen were extremely high and sometimes went right round the throat. This was an echo, as it were, of the boned necks of female attire.

The female silhouette began to be slightly modified in 1908. The bust was no longer thrust quite so far forward, nor the hips so far back. Floppy blouses hanging over the waist in front were abandoned. The fashionable ‘Empire’ gown, although bearing very little resemblance to the dresses worn in the time of Napoleon I, had the effect of narrowing the hips. This can be seen quite plainly in the corset advertisements of the period. Hats became wider, which had the effect of making the hips look narrower still.

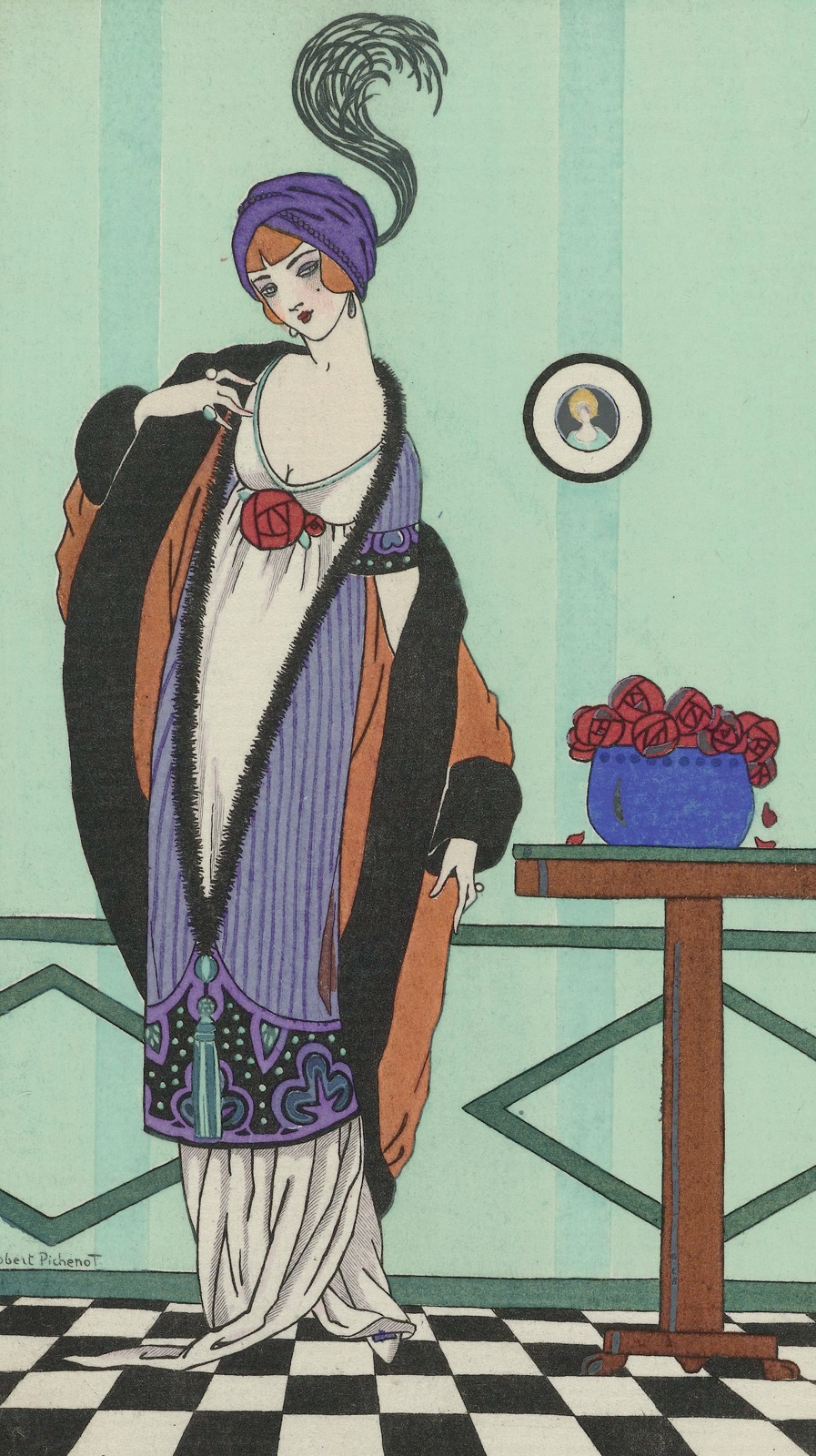

And then, in 1910, there was a fundamental change in female dress. There has been much argument as to what brought this about, but it was plain that the Russian Ballet had something to do with it, and so had Paul Poiret, and we need not trouble ourselves with the question of which came first. What is certain is that there was a wave of Orientalism following the extraordinary excitement caused by the production of Schéhérazade, the costumes for which were designed by Leon Bakst. The colours were striking, even garish, and society adopted them with enthusiasm. The old pale pinks and ‘swooning mauves’ were swept away; the rigid bodices and bell-shaped skirts were abandoned in favour of soft drapery. Skirts became narrow at the hem, and in 1910 extremely so, resulting in the hobble skirt which made it difficult for a woman to take a step of more than two or three inches. To prevent women from taking a longer stride and so splitting the skirt, a fetter made of braid was sometimes worn. It was as if every woman – and this in the very year of the Suffragette demonstrations – was determined to look as if they belonged to an Oriental harem. Some women even went so far as to wear little ‘harem’ trousers visible below the hem of the skirt, but these created such a sensation when worn in the street that only the most daring persisted. With the extremely narrow skirt went very large hats. The silhouette, in complete contrast to that of the woman of 1860, was a triangle standing on its point. The favourite trimming of dresses was no longer lace but buttons, which were sewn all over, even in the most unlikely places.

238 Male summer costume, July 1907.

239 Flannel suit for boating, July 1902.

240 Male motoring costume, c. 1904.

241 So-called ‘Merveilleuse’ dresses produced a sensation at the Longchamps races in May 1908. It was a strange delusion that these dresses resembled in any way the flimsy ‘Empire’ costumes of the 1790s.

242, 243 Emancipated woman: Hobble-skirt dresses (LEFT) and hobble garter (RIGHT), 1910.

244, 245 The new silhouette, still heavy above but tapering towards the feet, seen at race meetings in 1914.

Designers prospered. Lucile (Lady Duff-Gordon), who had made her mark by designing Lily Elsie’s costume for The Merry Widow in 1907, was, like Poiret, working on a romantic Oriental theme. She, and Charles Creed and Redfern, famous for their tailor-mades derived from men’s suits, all established branches in Paris at this time.

In 1913 came another startling change. Dresses no longer had collars coming up to the ears; instead there was what was known as the ‘V-neck’. This created an extraordinary amount of excitement. It was denounced from the pulpit as something very like indecent exposure and by doctors as a danger to health. A blouse with a very modest triangular opening in the front was dubbed a ‘pneumonia blouse’, but in spite of all these protests the V-neck was soon generally accepted. The collar, if there was one, now took the form of a small medici collar at the back of the neck.

Just before the outbreak of war there was another modification in the general outline of women’s dress. Over the skirt, which was very long and tight at the ankle, was worn another skirt, a kind of tunic reaching to just below the knee. The shape of hats also was modified. They were no longer excessively broad, but were small and fitted the head quite closely. Feathers, which were still fashionable, were no longer curled round the brim but stuck straight up into the air, and it was customary to wear two feathers projecting at an angle. These hats continued into the war period, but many women found the double skirt an encumbrance in the war work in which many of them were engaged. They therefore abandoned the underskirt and wore the tunic or overskirt by itself. The simple tailor-made was also popular, many women feeling, quite rightly, that extravagant dressing was out of place in wartime. The war, in fact, as all wars do, had a deadening effect on fashion, and there is little of interest to record until the conflict was over. For those who lived through the clothing restrictions and coupons of World War II, it is interesting to note that, in 1918, there was an attempt to introduce a National Standard Dress, a utility garment, with metal buckles instead of hooks and eyes, and designed, to quote a contemporary, as an ‘outdoor gown, house gown, rest gown, tea gown, dinner gown, evening dress and nightgown’. Nightgown is surely the only surprising item in this list.

246, 247 Mme. Paul Poiret modelling clothing designed by her husband, showing Oriental influence 1913.

248 Poiret design showing Oriental influence, 1914.

249 At home, 1913. The graceful mode of the period just before World War I.

250, 251, 252 Pre-war fashions. Day dress, 1912 (ABOVE, LEFT); Day dress, 1914 (ABOVE, RIGHT); Evening dress by Paquin, 1913 (BOTTOM).

In 1919, when fashion picked up again, the flared skirt which had lasted throughout the war was replaced by the so-called ‘barrel’ line. The effect was completely tubular. Skirts were still long, but an attempt was made to confine the body in a cylinder. The bust was entirely boyish, and women even began to wear ‘flatteners’ in order to conform to the prevailing mode. The waist disappeared altogether, and there were already many examples of the waistline round the hips which was to be so characteristic a feature of the middle of the decade.

253 Utility clothes, World War I.

And then, in 1925, to the scandal of many, came the real revolution of short skirts. They were denounced from the pulpit in Europe and America, and the Archbishop of Naples even went so far as to announce that the recent earthquake at Amalfi was due to the anger of God against a skirt which reached no further than the knee. The secular establishment was equally disturbed, especially in America, and, undeterred by the fact that sumptuary laws have had only minimal success throughout history, the legislators of various American states tried once more to impose their own view of morality. In Utah a bill was brought in providing fines and imprisonment for those who wore on the streets ‘skirts higher than three inches above the ankle’; and a bill introduced into the Ohio legislature sought to prohibit any ‘female over fourteen years of age’ from wearing ‘a skirt which does not reach that part of the foot known as the instep’. It was all to no avail.

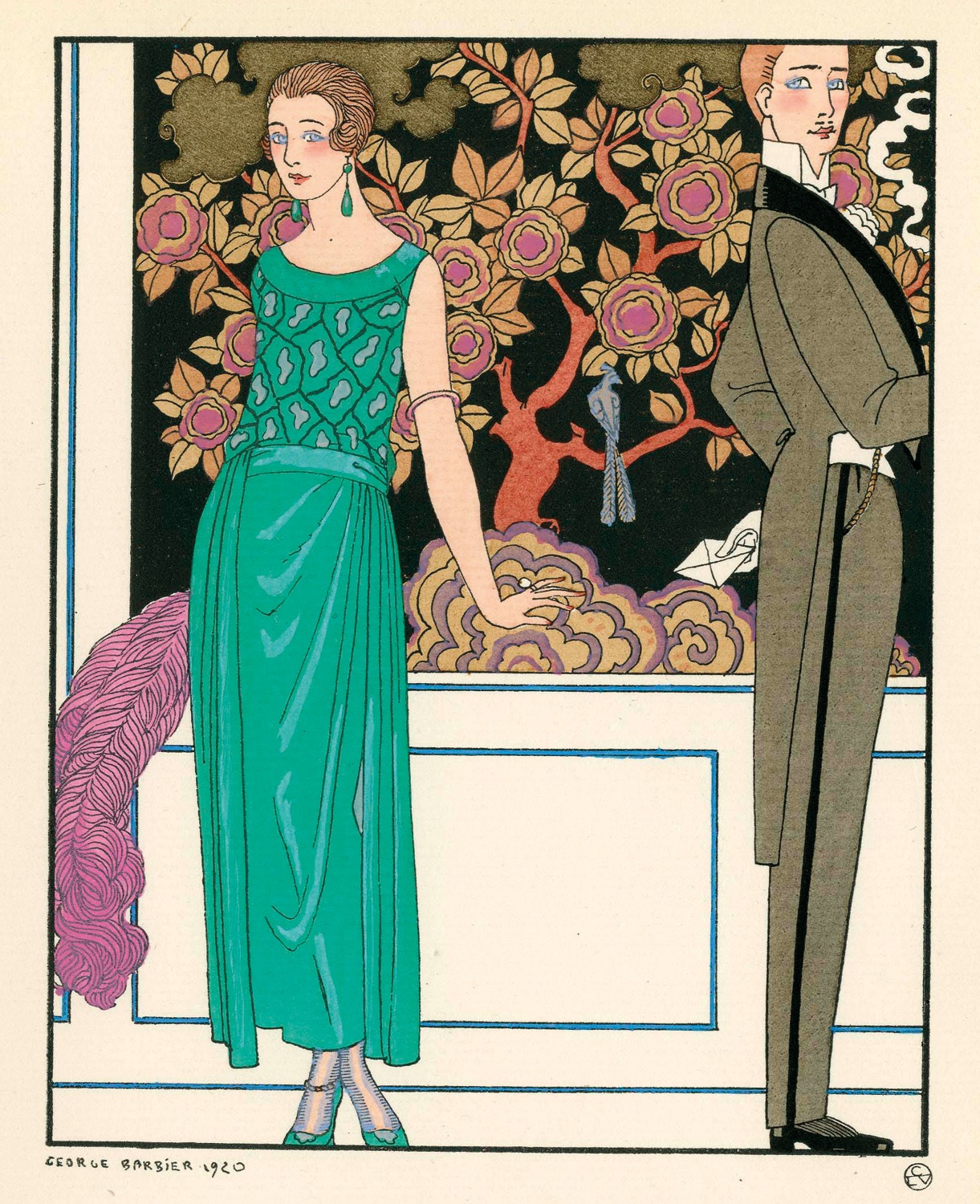

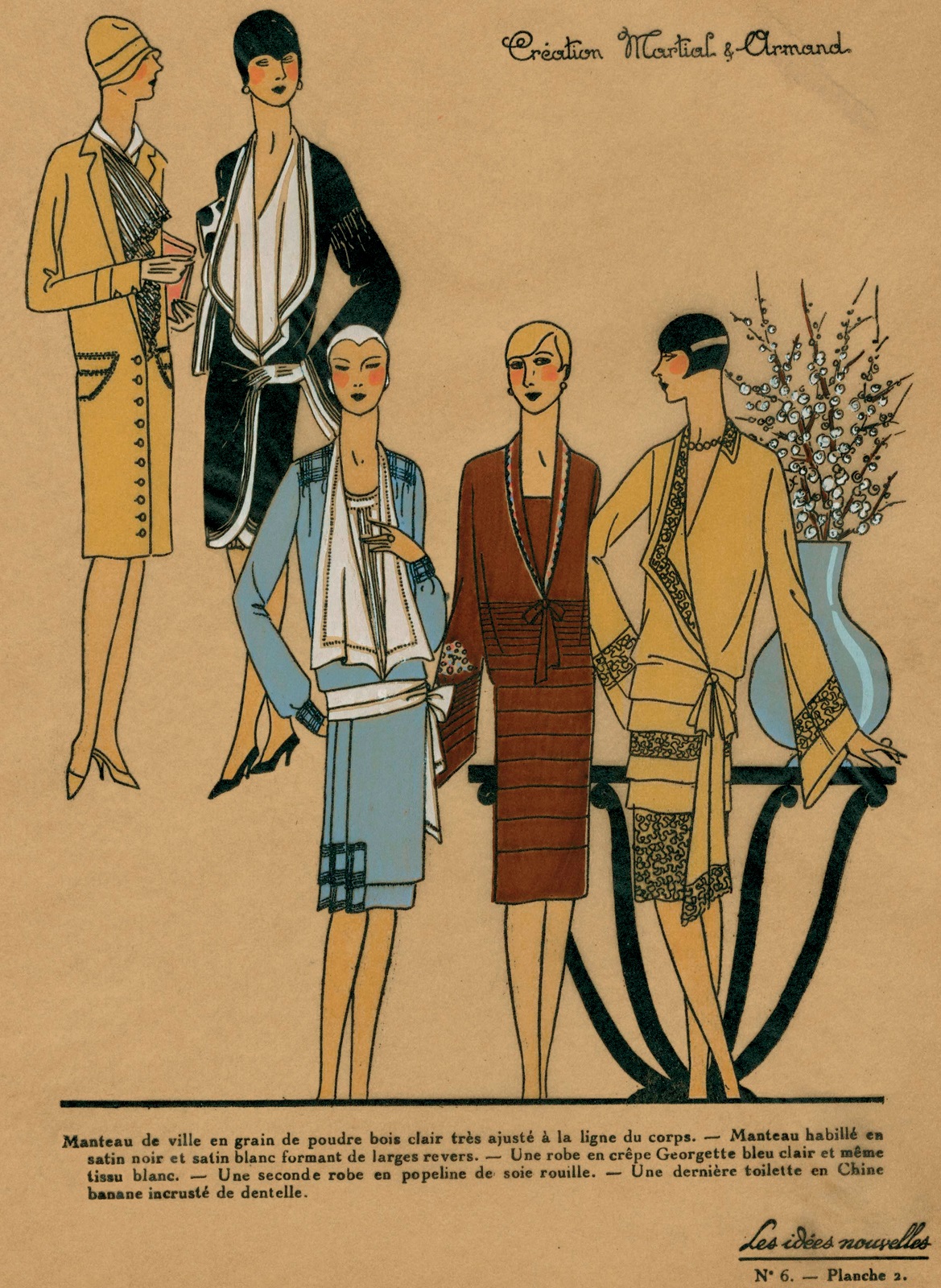

254 Day dresses, 1922.

255 The early 1920s: the line is tubular but the skirt is still long. Evening dress, 1921

256 Foulard silk summer dress, 1920.

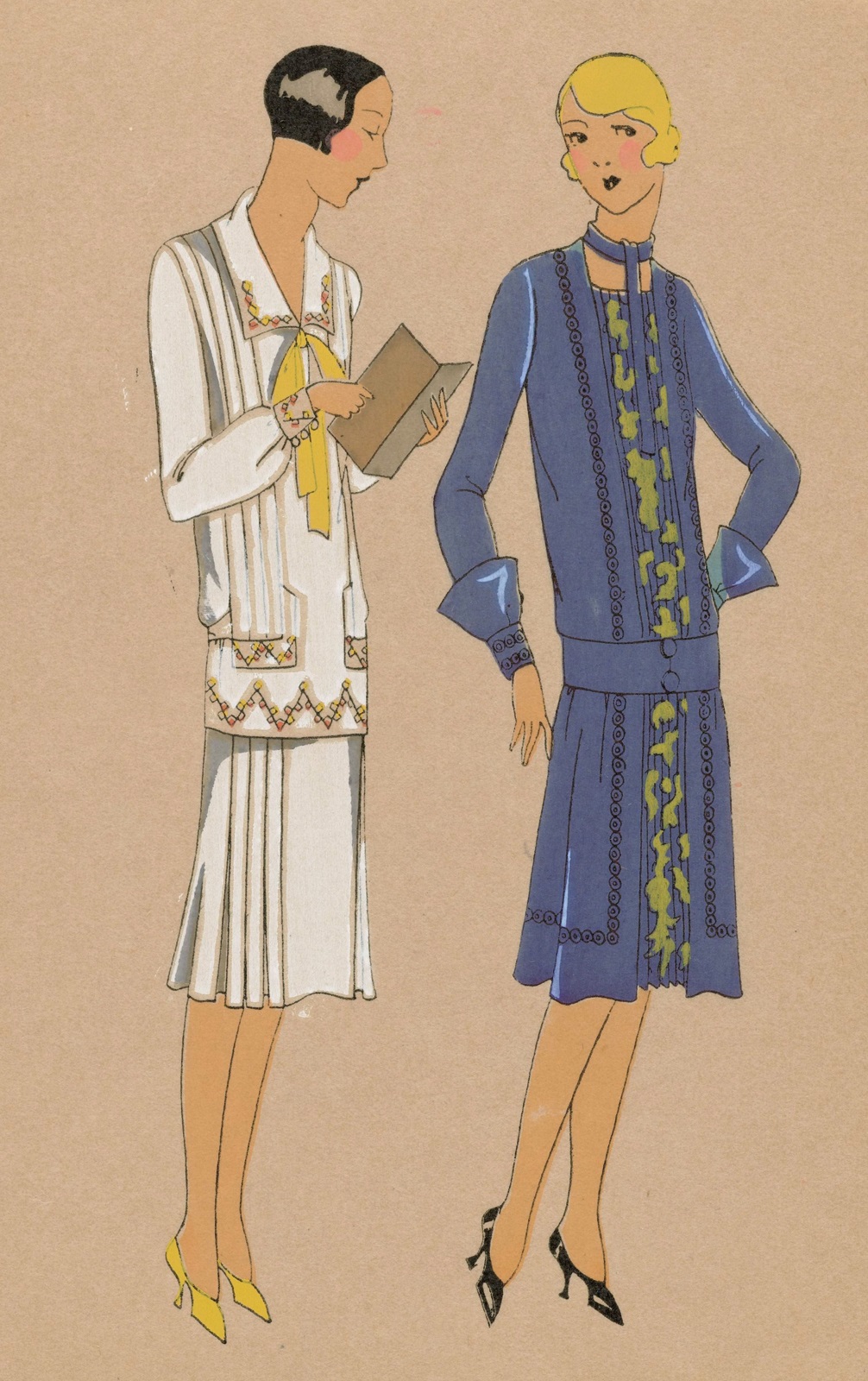

257 Summer dresses, 1926. The short skirt and the androgyne silhouette is now established.

258 Dresses, 1927.

A new type of woman had come into existence. The new erotic ideal was androgyne: girls strove to look as much like boys as possible. All curves – that female attribute so long admired – were completely abandoned. And, as if to give the crowning touch to their attempted boyishness, all young women cut off their hair. The bob of the early 1920s was abandoned for the shingle, which made the coiffure follow much more closely the lines of the head. Even older women were compelled to conform, because the cloche hat, which had now become universal, made it almost impossible to have long hair. Early in 1927 even this was not considered enough, and the shingle was succeeded by the Eton crop. There was now nothing to distinguish a young woman from a schoolboy except perhaps her rouged lips and pencilled eyebrows.

A curious result of the new modes was that they notably diminished, or at least threatened, the dominance of the great Paris fashion houses. The Frenchwoman does not naturally look like a boy; she did not fit into the new fashions as easily as her contemporaries in England and the United States. As a commentator of the time remarked, ‘the angular English woman, over whose lack of embonpoint papers like La Vie Parisienne have been making merry for two generations, now became the accepted type of beauty’. Several famous Paris firms, such as Doucet, Doeuillet and Drécoll, who had created the glories of la belle époque, closed their doors; and even Poiret, who had done so much to revolutionize fashion in 1910, now found himself completely out of tune with the times. New names emerged, many of them women. Madame Paquin, although she was head of a long-established firm, managed to conform to the new trend. Madeleine Vionnet accepted it with enthusiasm; but the outstanding revolutionary talent of the Twenties was undoubtedly ‘Coco’ Chanel, only rivalled a few years later by the astonishing figure of Elsa Schiaparelli. These two women were not merely dress designers; they formed an important part of the whole artistic movement of the time. Madame Chanel was an intimate friend of Cocteau, Picasso and Stravinsky. Madame Schiaparelli was fantastically successful, and it has been estimated that by 1930 the turnover of her establishment in the rue Cambon was something like a hundred and twenty million francs a year. Her twenty-six workrooms employed more than two thousand people.

What the fashion people found so shocking about her was her introduction of ‘good working-class clothes’ into polite society. She was accused of having brought the apache into the Ritz; but however simple her clothes might be, they always had an elegance which made everyone admire and copy them.

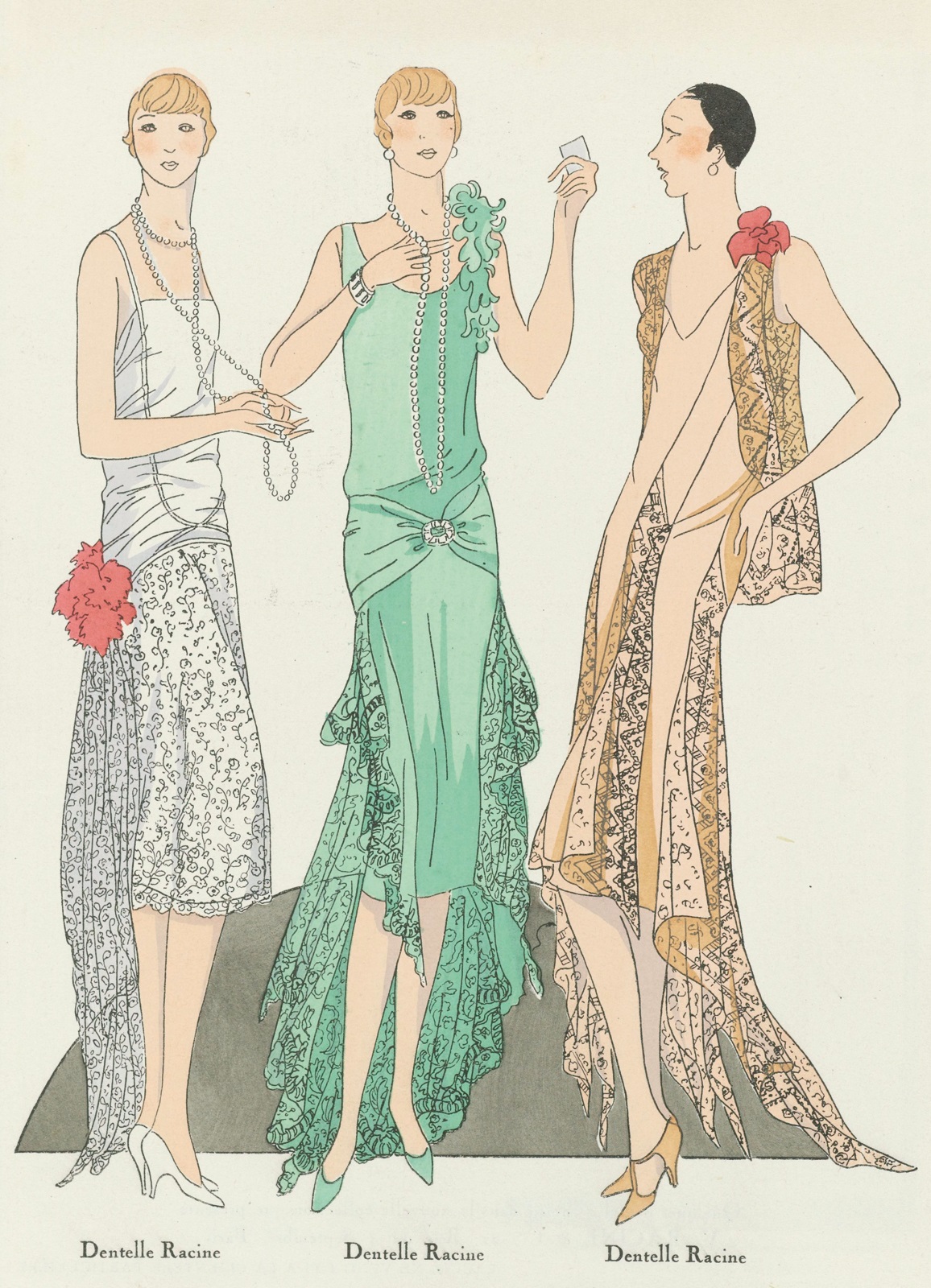

The function of fashion is to change, and by the end of the 1920s it was plain that a new style was about to be evolved. Skirts reached the extreme of shortness (the extreme, that is, until modern times) in 1927. It was not in everybody’s interest that skirts should be short. It is true that the manufacturers of silk stockings were enjoying a boom, but the skimpy dresses of the period did not bring much profit to cloth manufacturers or the designers of accessories. It was plain that attempts were being made to bring skirts down again and, as so often happens, the first experiments were made with evening dress. Skirts remained short, but they were sometimes provided with a gauze overskirt which was somewhat longer; or long panels were added at the side. Another expedient, and an extremely ugly one, was to make the skirt longer at the back than the front. There were even examples which came down to the knees at the front and trailed on the ground behind, and this ugly and preposterous fashion lasted for nearly a year.[265]

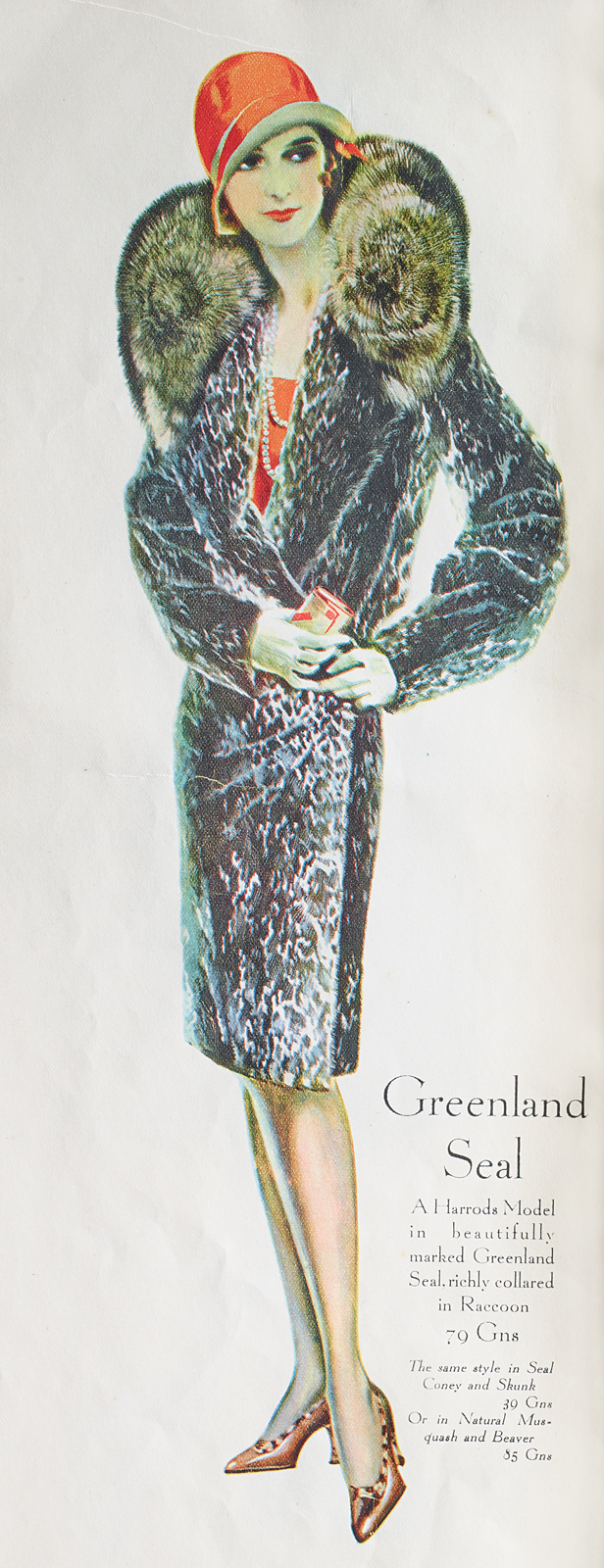

259 Lady’s coat, mid-1920s.

260 Corset advert, 1925.

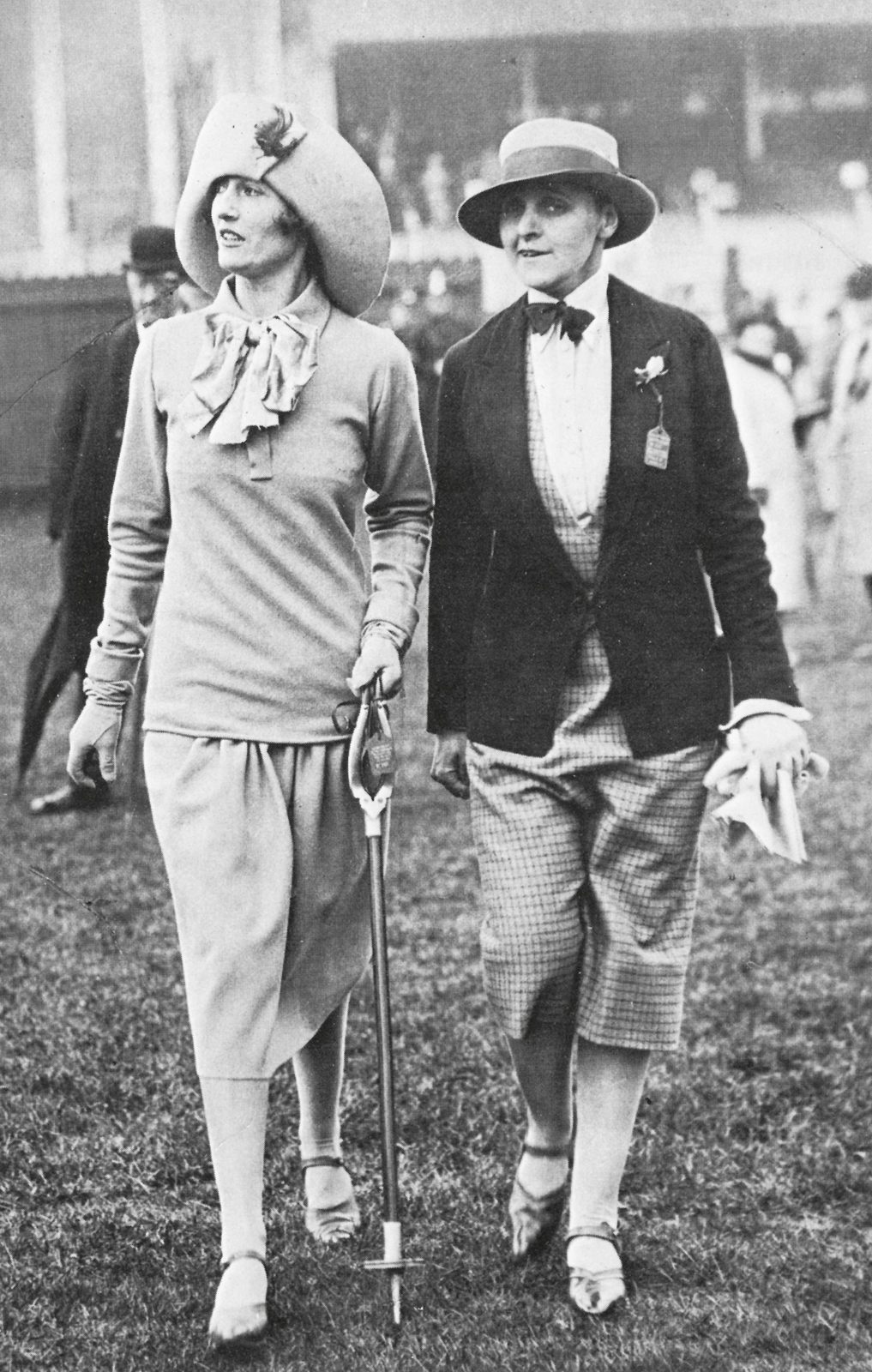

261 At Chester races, 1926. Masculine elements in female costume.

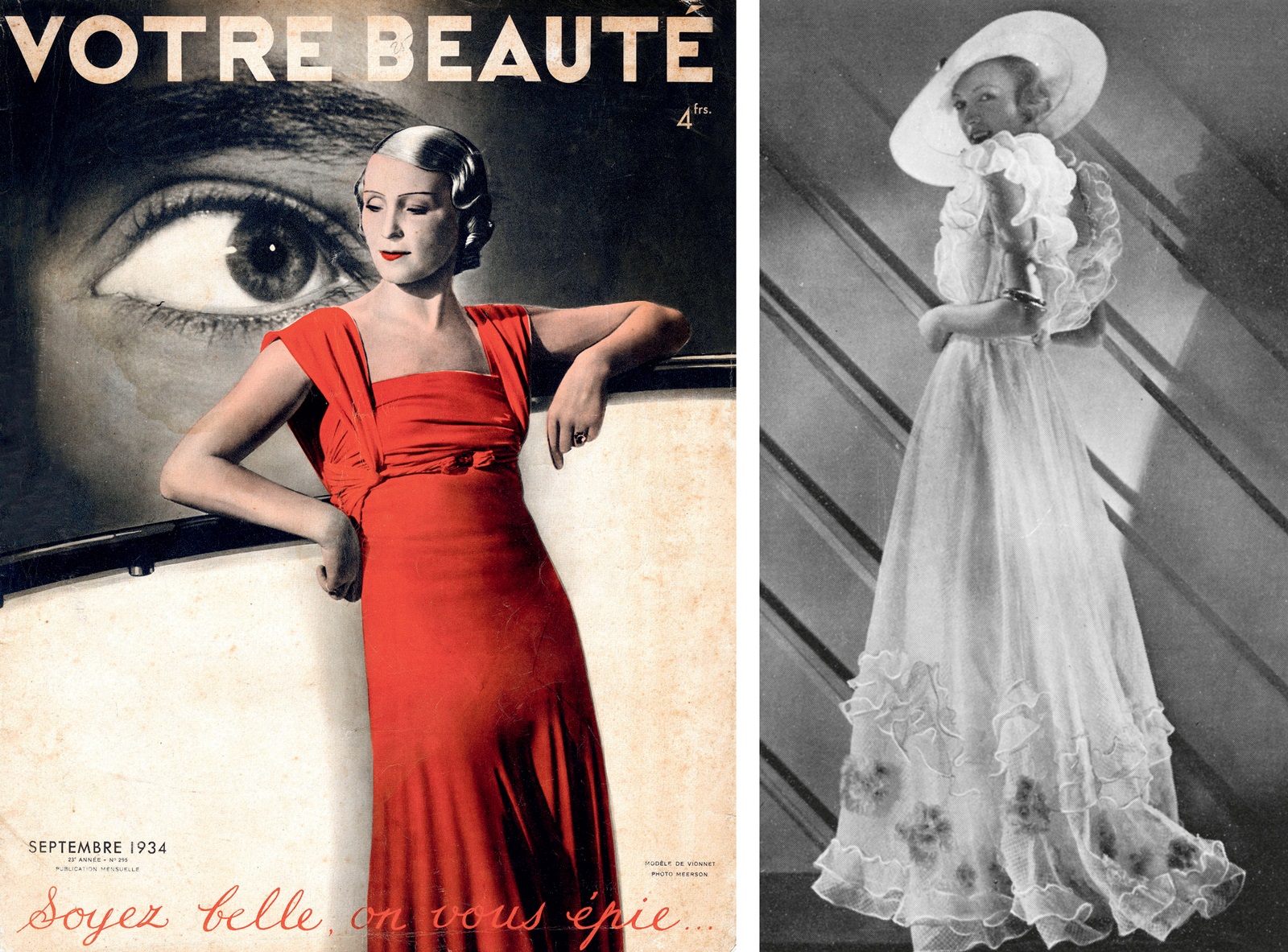

Then, as the decade drew to its close, skirts suddenly became long again and the waist resumed its normal place. It was as if fashion were trying to say: ‘The party is over; the Bright Young Things are dead.’ As in 1820, the return of the waist to its normal position symbolized a movement towards a new paternalism: in economic terms the American Slump; in political terms the rise of Hitler. The cloche hat, which had tyrannized over the mode for nearly ten years, was abolished and women were free to grow their hair again. The long sleeves were seen once more; but there is no exact parallel between the fashions of the early 1930s and those of a century before, for the waist did not become excessively tight and the general lines of the skirt remained more or less perpendicular. Wide shoulders and slender hips seemed to be every woman’s ideal, exemplified in the figure of Greta Garbo. In the 1930s, especially, film actresses were almost arbiters of fashion, their costumes created by designers such as Gilbert Adrian.

262 Afternoon coat, 1928.

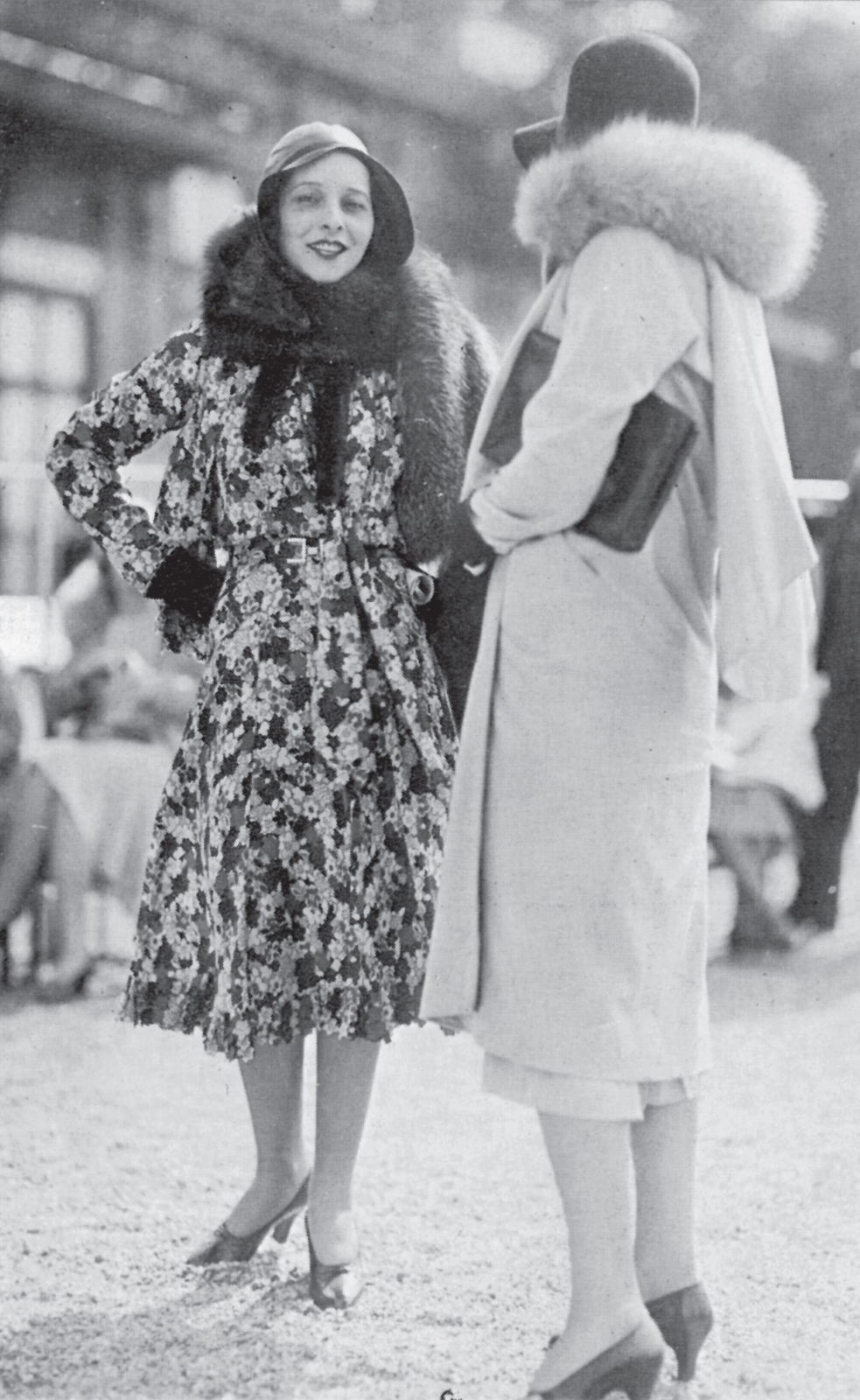

263 At the races, Longchamps, 1930. The skirts are on the eve of going long again and the waist is about to resume its normal place.

264 ‘Pierrette’ hairstyle by Lanvin, 1928.

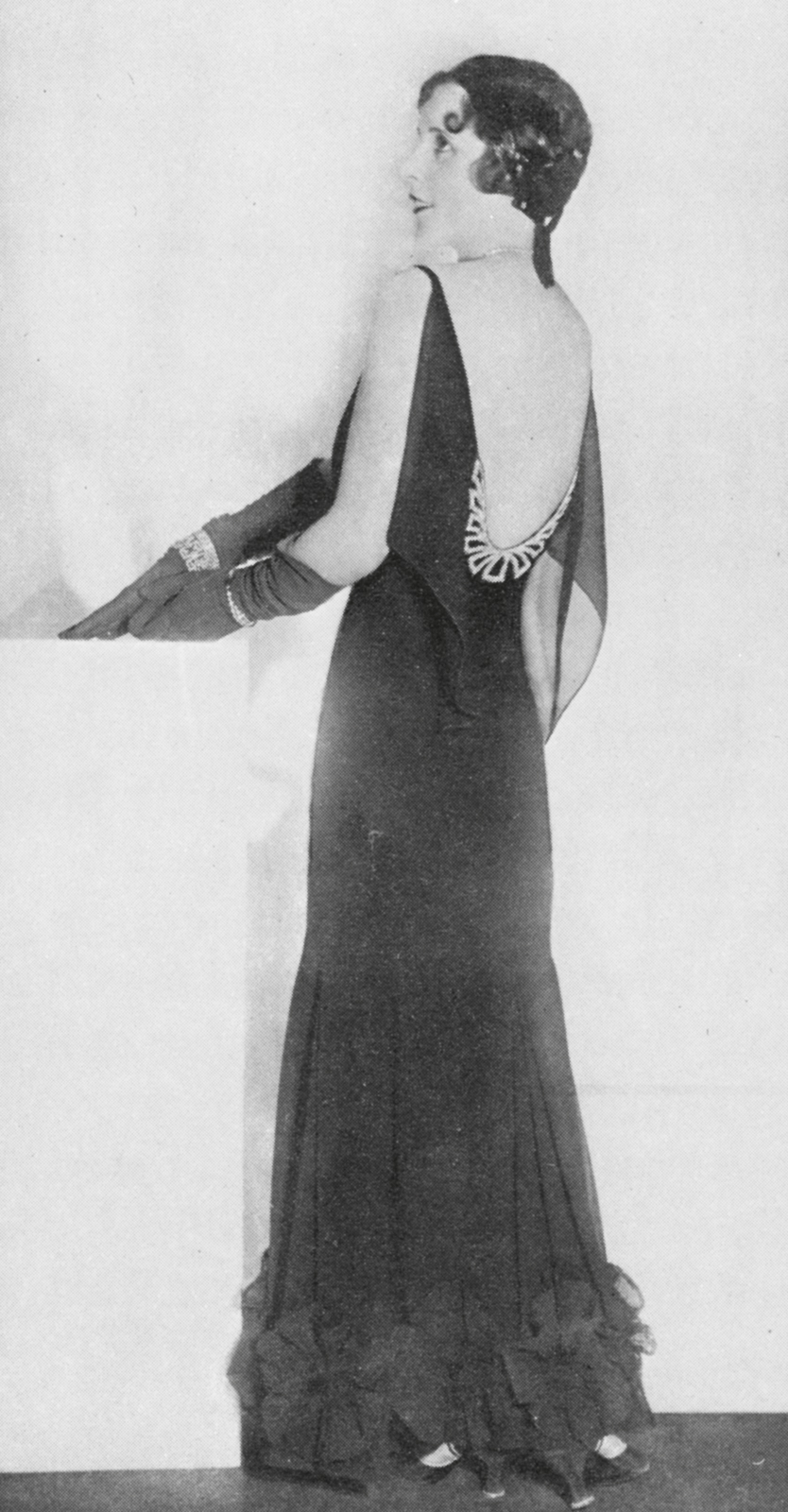

If the psychologists’ theory of the Shifting Erogenous Zone can be accepted, once a focus of interest loses its appeal another one has to be found. In the early 1930s the emphasis shifted from the legs to the back. Backs were bared to the waist and, indeed, many of the dresses of the period look as if they had been designed to be seen from the rear. Even day dresses had a slit up the back, and the skirt was drawn tightly over the hips so as to reveal, perhaps for the first time in history, the shape of the buttocks.

265 Evening dress, 1929. At the end of the 1920s the couturiers made definite efforts to bring in long skirts again by various devices such as transparent hems, side-pieces and trains.

266, 267 Day (LEFT) and evening (RIGHT) dress by Lanvin, 1931.

268 Evening dress by Worth, 1930. An example of the new focus of erotic interest: a dress designed to be seen from the back.

It seems likely that this backlessness had something to do with the evolution of bathing costumes. The bathing costumes of the 1920s were surprisingly modest; fashion photographs of the period show mannequins in quite ample overskirts and extremely limited décolletage. In the early 1930s all this was changed. What really brought this about, however, was not bathing, but sunbathing, which was now enjoying a tremendous vogue. If, as some fanatics claimed, the exposure of the skin to sunlight was the way to health for everybody, then obviously the greater portion of skin exposed the better. The overskirt of the bathing costume was therefore reduced to almost nothing, the armholes were enlarged and the décolletage was much deeper. Finally, the first backless bathing costume appeared, although, in fact, it was no more backless than the evening dress of the same period.

In addition to bathing, other sports were beginning to have a marked influence on ordinary costume, although we should note also the opposite tendency of sports clothes to develop a type of their own; this is particularly noticeable in the case of tennis. Most tennis players had simply worn the summer clothes of the period, even if the skirts were long and hampering to the movements. In the 1920s, when the skirts of ordinary dress were short, tennis costume followed suit, but when skirts became long again at the end of the decade, tennis dress went on, so to speak, on its own, since it was plainly absurd to reintroduce long skirts in what had now become a strenuous game. In April 1931 Señorita de Alvarez played in divided skirts which came to slightly below the knee, and two years later Alice Marble of San Francisco appeared in shorts above the knee. It was left to Mrs Fearnley-Whittingstall to appear at Wimbledon without stockings. This caused an uproar, but the new mode was so obviously sensible that it was soon adopted by almost all women players.

269 Evening dress, 1932. The sleek lines of the decade are already visible.

A similar evolution can be seen in skating costume, which by the early 1930s had crystallized into a kind of uniform, having a skirt with wide flares, at first knee-length but afterwards much shorter. Cycling, although it had long ceased to have any appeal to the upper classes, was still extremely popular, and most young women adopted shorts, sometimes so short that considerable opposition was aroused when English cycling clubs went abroad.

270 At the races, 1930.

271 Suit, 1935. An extreme example of the exaggerated shoulder.

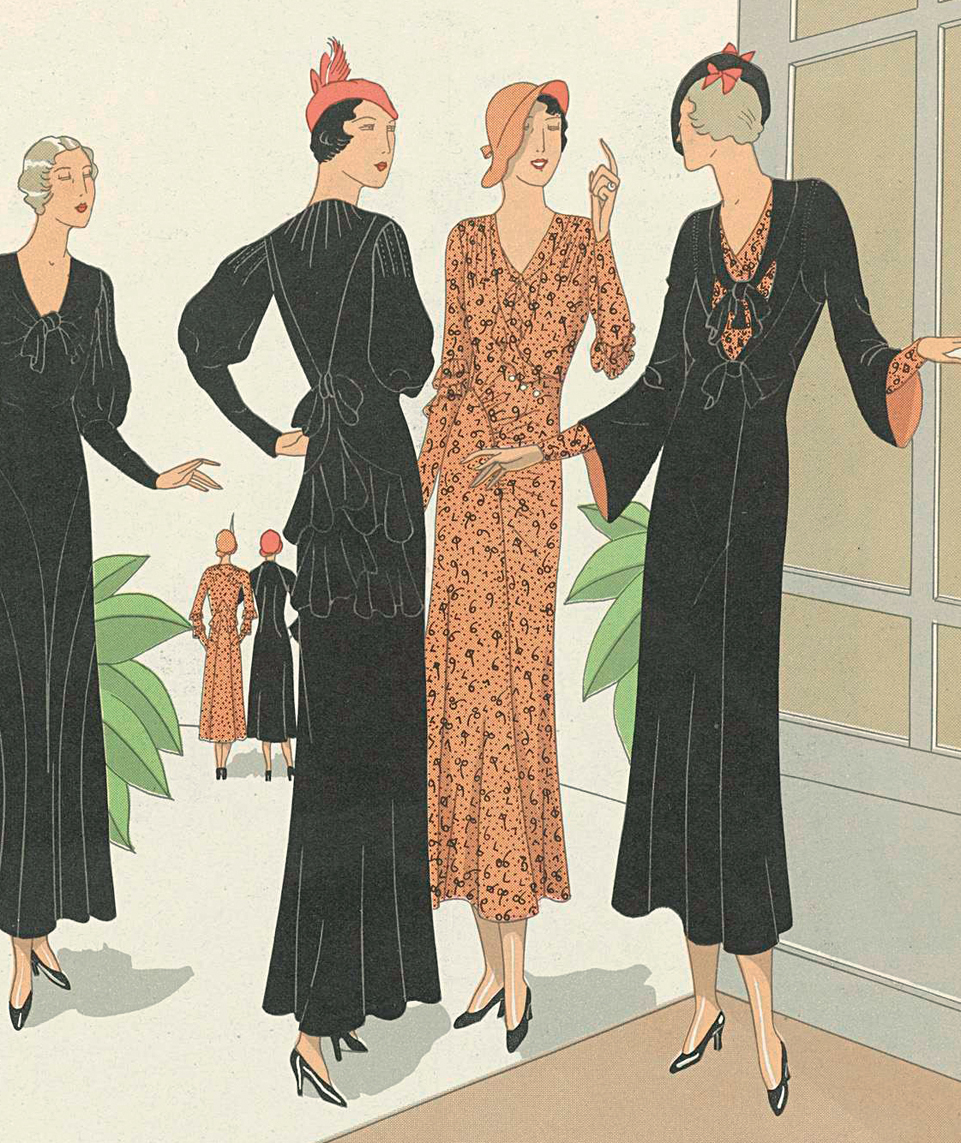

The main lines of women’s clothes in the early 1930s may be briefly summarized. Dresses were slim and straight, being sometimes wider at the shoulders than at the hips. Tall girls were admired, and all the tricks of the couturier were employed to give the impression of increased height. This effect can be increased by making the head look small, and so the hair was dressed rather close, with a small curl at the back of the neck. On top was a gay little hat perched over one eye. Day dresses usually came to about ten inches above the ground, while evening dresses reached to the toes. Both evening and afternoon dresses were often provided with little capes. The bolero was extremely fashionable. Perhaps as a gesture of economy, evening dresses were sometimes made of woollen or cotton materials and even of broadcloth, previously thought suitable only for day wear.

The Depression certainly helped to bring the clothes of the different classes closer together, at least in general line, and now a new process had begun which brought the creations of the great Paris houses within the reach of nearly every woman. Before 1930 it had been the habit of buyers (especially American buyers) to purchase several dozen copies of each selected model shown in Paris and resell them to a wealthy clientele. But after the Slump the American authorities imposed a duty of up to 90 per cent on the cost of the original model. Toiles (i.e. patterns cut out in linen) were allowed in duty-free. Each toile was supplied with full directions for making it up, and although the original dress may have cost a hundred thousand francs, it was now possible to sell a simplified version for as little as fifty dollars. Another factor which contributed to the same end was the growing use of synthetic fabrics. Even the factory girl could now afford to purchase artificial silk stockings.

272, 273 The bosom has not yet reasserted itself after the flat styles of the 1920s. Cover of Votre Beauté, September 1934 (LEFT); Summer dress, 1934 (RIGHT).

As the clouds of World War II began to gather, it became obvious that the fashionable silhouette was beginning to be modified, even if the fashion designers were as puzzled as the general public about what the dominating trend would be. There was a new wave of romanticism stimulated by the visit of the King and Queen to Paris in the early summer of 1938.’Never’, says C. Willett Cunnington, ‘has Fashion been more ironic than in this attempt to revive, for an evening dress, the modes current on the eve of the Franco-Prussian War’ (English Women’s Clothing in the Present Century). There was even an attempt to revive the crinoline. Day dresses, however, showed an opposite tendency. The skirt was shorter and was bunched up in the peasant style. Curiously enough it was an Austrian peasant style, as if in unconscious acknowledgment of the growing power of Hitler. But right up to the eve of the conflict the majority of fashion designers, consciously or unconsciously, were betting that there would be no war. There was even an attempt to bring in tight-lacing again.

In the summer of 1939 Vogue’s reporter noted the extraordinary variety of models offered by the leading houses, and added: ‘Nothing varies more than silhouette. You can look as different from your neighbour as the moon from the sun – and both of you are right. The only thing that you must have in common is a tiny waist, held in if necessary by super-light-weight boned and laced corsets. There isn’t a silhouette in Paris that doesn’t cave in at the waist.’

The accentuated waist was a boon to advertisers, who called upon women to ‘control it with corsets…where there’s a will there’s a way!’ Women were promised ‘an old-fashioned boned, laced corset, made, by modern magic, light and persuasive as a whisper’. Perhaps, if peace had been preserved, women in the 1940s would once more have confined their waists in a rigid cage. History, however, decreed otherwise.

274, 275 ‘Butterfly’-sleeve dresses, 1934.

276, 277 Fashion shows in a salon, 1935.

But for the moment it seemed that nothing had changed. Most of the great Paris houses launched their usual collections in the spring of 1940. It was the period of the ‘phoney war’, and no one in England or France or even America seemed to realize that the second great conflict of the twentieth century was really upon them.

Men’s clothes continued the progress towards informality which had been noticeable since the end of World War I. After the Armistice the frock coat had become something of a rarity, and its rival the morning coat was to be seen only at weddings, funerals or some occasion when royalty was present. The lounge suit had now become ordinary town wear, but after 1922 it was shorter and had no slit up the back. The decay of the waistcoat led to a new increase in the popularity of double-breasted coats. The single-breasted coat, however, still continued, and in the later Twenties there was a craze for double-breasted waistcoats to go with it.

The chief change in the mid-1920s was in the width of trousers, the so-called ‘Oxford bags’. It is thought that these may have originated from the extremely ample trousers made of towelling worn by undergraduate oarsmen over their shorts. It was customary for the coach to ride a horse along the towpath wearing these trousers, and since he was a person of considerable prestige, undergraduates in general adopted the mode. Certainly they were to be seen everywhere, and were sometimes so wide that only the tip of the shoe was visible and the trousers flapped about the leg in the most extraordinary fashion. So strange a mode was not likely to last long, and by the end of the 1920s extremely wide ‘Oxford bags’ had disappeared, but trousers remained fairly wide until the end of the 1930s.

278 At the races, 1938. Hats during the 1930s were a little mad in reaction against the universal cloche of the previous decade.

279 Paris fashions, 1939.

280 Male fashions for spring and summer, 1919–22.

Meanwhile knickerbockers had been enjoying a renewed boom. For some obscure reason the breeches worn by Guards officers during World War I differed from the riding breeches of officers in Line Regiments by being extremely baggy and so loose as to hang over the top of the puttees. These had a strange effect on ordinary knickerbockers, which began to be cut, immediately after the war, in the same fashion, only even more amply. The new baggy knickerbockers were known as ‘plus-fours’, being considered especially suitable for golf. They completely drove out the old knickerbocker costume, which henceforward was worn only by old-fashioned intellectuals. They were in many ways the most typical sartorial invention of the period between the wars.

281 Examples of the new informality: M. Herriot (LEFT) in the French style and Mr Ramsay Macdonald (RIGHT) in the English style, 1924.