Apprenticeship, 1527–1543

ON 10 March 1526 Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of Spain, Mexico, the Netherlands and much of Italy, rode into the bustling city of Seville for the first time. Still in his travelling clothes and covered in dust, he dismounted in the courtyard of the royal palace and strode into the room where Princess Isabella of Portugal, his cousin, was waiting. The pope had already sent a dispensation to permit the two cousins to marry in Lent, and their representatives had already signed the marriage contract; so, after 15 minutes of polite conversation with the fiancée he had never seen, Charles changed into his finest clothes, attended a nuptial mass and danced. Then at 2 a.m. the couple went to bed and consummated their union.

The first weeks of married life for the imperial couple proved idyllic. They stayed ‘in bed until 11 or 12’ each morning and gave ‘every sign of contentment’ after they emerged.1 They and their retinue then travelled slowly to Granada to pay their respects to their common ancestors buried in the cathedral, planning to continue their stately progress to Barcelona whence Charles would depart to lead a crusade against the Ottoman Turks, leaving his wife to govern Spain; but then news arrived that King Francis I of France had declared war on him. This precluded the emperor’s departure from Spain. He and his wife therefore spent the next six months in Granada, hoping that the international situation would improve, and in the Alhambra high above the city the future Philip II was conceived. The English ambassador was the first to find out. ‘The empress is with child, at which all the people are delighted,’ he wrote on 30 September 1526 – the first known mention of the future king. The empress remained in Granada, resting, until early the following year when she travelled slowly to join her husband in Valladolid, then the administrative capital of Castile.2

As is often the case with a first child, the empress was in labour for many hours. She asked for a veil to be placed over her face, so that no one would see her agony; and when a midwife urged her to give full vent to her feelings the empress replied sternly: ‘I would rather die. Don’t talk to me like that: I may die, but I will not cry out’. Philip entered the world around 4 p.m. on 21 May 1527. Many Spaniards had expected the prince to receive one of the traditional names of the peninsular dynasties, such as Fernando or Juan, but Charles insisted on calling his firstborn after his own father, and so at the baptism ceremony two weeks later the royal heralds shouted three times: ‘Philip, by the grace of God prince of Spain!’ But Philip was heir to far more than Spain.3

The inheritance

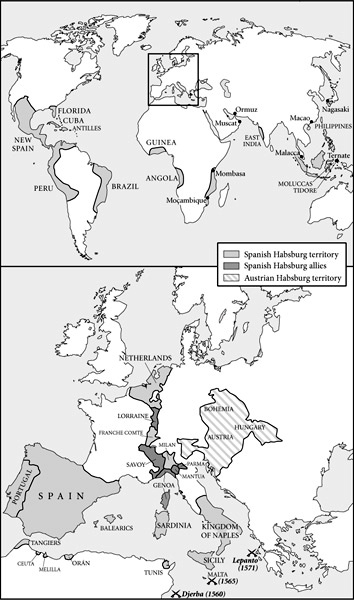

Dynastic accident had brought together in the person of Charles V four separate inheritances. From his father’s father, Emperor Maximilian of Austria, Charles received the ancestral Habsburg lands in central Europe; from his father’s mother, Mary of Burgundy, he inherited numerous duchies, counties and lordships in the Netherlands and the Franche-Comté of Burgundy. From his mother’s mother, Queen Isabella the Catholic, Charles received Castile and its outposts in North Africa, the Caribbean and Central America; from his mother’s father, Ferdinand the Catholic, he inherited Aragon and the Aragonese dominions of Naples, Sicily and Sardinia. Charles soon added more territories to this impressive core of patrimonial states: several provinces in the Netherlands by treaty; the duchy of Lombardy in Italy when its native dynasty died out; and Tunis in North Africa by conquest. Most spectacular of all, in the Americas, about 2,000 of his Spanish subjects destroyed the Aztec empire and occupied an area eight times the size of Castile, whence fewer than 200 of them began the conquest of the Inca empire in Peru. In 1535, as he entered the city of Messina in Sicily, Charles V saw for the first time the felicitous phrase coined by the Roman poet Virgil for the possessions of the Emperor Augustus, fifteen centuries before: A SOLIS ORTU AD OCCASUM, ‘from the rising to the setting of the sun’ – or, as his ‘spin doctors’ would put it, ‘an empire on which the sun never set’.

No European ruler had ever controlled such extensive territories, and the absence of precedents helps to explain the apparently haphazard nature of decision-making by the Spanish Habsburgs: they had no choice but to improvise and experiment, to test different techniques of government as they went along, to learn by trial and (sometimes) error. In any case, prior experience might not have helped, because for most of his reign Charles faced an unpre-cedented combination of enemies: two religious, the Protestants and the Papacy, and two political, France and the Ottoman empire.

A dangerous synergy between these enemies occurred after Maximilian died in January 1519, leaving two important items of unfinished business. The late emperor had failed to silence Dr Martin Luther, a professor at the University of Wittenberg in Saxony who wrote pamphlets and speeches to mobilize public support for his claims that the Papacy was corrupt and required urgent reform. Maximilian had also failed to arrange for Charles to succeed him as Holy Roman Emperor, paramount ruler of Germany, and throughout the spring and summer of 1519, Charles and Francis I paid huge sums of money to the seven Electors (Kurfürsten) who would choose the ‘king of the Romans’ (emperor-elect, pending papal coronation). Eventually, Charles won the contest, so that his territories now surrounded France to the north, east and south. In 1521 Francis declared war, and for over a century the kings of France would strive to end what they saw as Habsburg encirclement by the various territories inherited or acquired by Charles.

1. The Spanish Monarchy at its apogee, 1585. The annexation of Portugal and its overseas possessions made Philip the ruler of the first global empire in history. Although its core remained the Iberian peninsula, issues concerning Africa, Asia and America regularly flowed across Philip’s desk and required him to make countless decisions.

The popes, too, felt threatened by the Imperial election because Charles now ruled not only Sardinia and Spain to the west, and Naples and Sicily to the south, but also the Empire (and, after 1535, Milan) in the north. Moreover, Rome depended on grain exports from Sicily, while its entire commerce by sea and land lay at the mercy of the surrounding Habsburg bases. Papal support for the ‘crusades’ by Charles (and later by his son) against both Muslims and Protestants therefore tended to remain muted for fear that any further success would tighten their grip on Rome. The Ottoman sultans also saw Charles as their natural enemy. In the course of his long reign (1520–66), Suleiman the Magnificent led his troops up the Danube five times, on each occasion gaining lands either from the Habsburgs or from their allies. Only his need to deal with other foreign and domestic enemies prevented further advances.

Domestic enemies periodically distracted Charles, too. To begin with, the death of his grandfather Ferdinand of Aragon in 1516 left a contested inheritance. Although Ferdinand’s marriage to Isabella of Castile had created a dynastic union, it left intact the institutions, laws, currency and judicial structure of each of their possessions – Castile, Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia and Navarre (annexed by Ferdinand in 1512) – and the powers and policies of the crown differed in each area. Above all, although Ferdinand had been king consort of Castile during Isabella’s lifetime, when she died in 1504 his title lapsed and the crown passed to the couple’s oldest child, Juana, and her husband Philip of Habsburg, ruler of the Netherlands, Charles’s parents.

Juana, unlike her mother, showed neither desire nor aptitude for government and so Ferdinand and Philip vied for control of Castile. Philip won – but almost immediately died, whereupon Ferdinand dismissed the officials appointed by his son-in-law, most of whom (later known as ‘Philippists’) fled to the court of the young Charles in the Netherlands, where they spent the next decade plotting revenge. Ferdinand also placed Juana, although ‘queen proprietress’ of Castile, in preventive custody and acted as ‘governor’ of the kingdom. In his last testament he named Charles his sole heir and in 1517 the prince and the ‘Philippists’ arrived from the Netherlands to take charge. Two years later Charles’s election as Holy Roman Emperor obliged him to return to northern Europe to restore order in Germany, and in his absence major anti-Habsburg uprisings broke out in Mallorca, Sicily, Valencia and, above all, Castile, where rebels known as the Comuneros sought to make Juana queen in fact as well as name. The emperor’s return to Spain in 1522 restored order there, but four years later Habsburg military and financial support failed to prevent Suleiman from advancing into Hungary. In desperation, Charles offered the Lutherans of Germany toleration in return for military assistance against the Turks. The spread of Protestant ideas now accelerated both within and beyond Germany.

2. The Family of Charles V. The House of Habsburg tended to produce either huge families or none at all. Thus of the fifteen children of Charles V’s daughter Maria (only eight of whom appear in the figure, for reasons of space) only Anne had offspring, of whom only one, the future Philip III, produced heirs. The rest apparently married too late to reproduce or did not marry at all. (Dashed lines in the chart indicate illegitmacy.)

Charles was powerless to halt these developments because his war with France and several Italian states kept him confined to Spain, so instead he orchestrated displays of rejoicing for the birth of Felipito (‘Little Phil’) as the emperor’s jester called him. According to an ambassador, ‘the Emperor is so happy, delighted and proud of his new son that he does nothing but order celebrations’. ‘Felipito’, of course, remained oblivious to this, and also to the ceremony in Madrid in 1528 at which his future subjects swore allegiance to him as prince of Castile. Instead, his attention focused on those who looked after him.4

Charles and Isabella continued to appear in public as ‘the happiest spouses in the world’, but although the empress doted on her husband, he saw his wife primarily in terms of administration and procreation.5 Thanks to the wet-nurses, the empress swiftly recovered her fertility and, three months after the prince’s birth, Charles left his newly pregnant wife as regent of Castile while he went to Aragon to meet its Cortes (the representative assembly), intending to travel on to Barcelona and thence to Italy; and when hostilities with France once again prevented his departure, he went to Valencia instead of returning to his wife’s side. Charles was therefore not present when Isabella gave birth to their second child, María, in June 1528. He returned a few weeks afterwards, but departed nine months later – once again leaving his pregnant wife to serve as regent. This time an advantageous peace with his enemies enabled Charles to sail across the Mediterranean to Italy. Although his new son, Ferdinand, died in infancy, the emperor did not return to see his wife and his surviving children again for four years.

‘Felipito’ therefore passed most of his infancy without a father. At age two he was weaned, and the following year he and his sister ‘spend their time competing to see who has more clothes’. An obsequious courtier informed Charles that his son ‘and his crossbow are such a threat to the deer that I fear that when Your Majesty returns [to Spain] you will have nothing left to kill’. Like all small children, the prince had his ups and downs. In 1531, when he ‘organized the children’ at court for a mock joust ‘using lighted candles as lances’, everyone laughed. They laughed again when Philip tried to persuade a courtier to accept one of his page boys ‘because he had lots of them’, and when the courtier refused he offered ‘the page to his sister, who had none; and they replied that it was not so easy to find pages. To this he replied angrily “Then find another prince: you will find lots of them in the streets”’ (Philip’s first recorded dialogue). At other times, however, ‘His Highness becomes angry when he does not get to eat what he wants. He can be so tiresome’ that his mother ‘becomes really annoyed and sometimes smacks him’.6

At age four, Philip refused to travel with his mother in her carriage; instead ‘he wanted the Infanta [María] to travel in it with him, because he enjoys her company so much – which suggests that he will be quite a lady’s man’. The prince also refused to ride his mule side-saddle: ‘He would only ride if he had his feet in the stirrups’.7 On the feast of St James, 1531, for attending a ceremony in a convent at which three young women became nuns, the prince discarded the long robes then worn by infants of both sexes and appeared for the first time in the doublet and hose worn only by boys. Henceforth, although still accompanied everywhere by his mother, her ladies and his sister, the prince began to attend tournaments, festivals and other public activities. He had begun to move from the private to the public stage.

The empress’s decision to hold this rite of passage in a convent reflects not only her own devotion but also the pious zeal of the two other women who oversaw the young prince’s welfare: Doña Inés Manrique de Lara and Doña Leonor de Mascarenhas. The former, from an eminent Castilian family, had served Isabella the Catholic and then retired to a nunnery, where her exemplary piety earned her the reputation of a holy woman (beata). No doubt it was this that led the empress to summon Doña Inés to court to serve as her son’s governess (aya), responsible for his physical and moral welfare. Doña Leonor, who was much younger and had migrated from Portugal to Castile in the empress’s entourage, also lived as a beata. Although lacking the official title, she acted as informal governess to the prince. The religious zeal of these two women mirrored that of the empress: practical, ascetic and intense. Before Philip’s conception, Isabella ordered special masses to be said to ensure her fertility and made a vow to the church of Santa María la Antigua in Seville that she would give a silver statue of a child as an ex-voto for every child that she conceived (her testament stipulated that five silver statues should be made and delivered to the church). She gave birth surrounded by the collection of relics she had brought with her from Portugal and clutching ‘St Elizabeth’s girdle’, which the mother of John the Baptist had reputedly held during her labour; afterwards she sent the garments that her son had worn before and after his baptism to be blessed by another beata, who sent back some of her own garments so that, according to a chronicler, ‘the prince should be swaddled in them and thus protected from attacks by the Devil’.8

Philip survived not only ‘attacks by the Devil’ but also the normal hazards of childhood. One day he strayed outside the railings on the edge of an upper floor of the palace, and such traumatic events, coupled with the death of the empress’s second son Fernando, profoundly affected Isabella. Henceforth, she panicked at the slightest illness in her surviving children, especially Philip, and her spirits sagged whenever Charles was away. According to a foreign ambassador, ‘her depression stems from the loss of the Infante, who enjoys God’s glory, and from the ailments of the prince, but above all from the absence of her husband’.9 Then, in spring 1533, news arrived that Charles would come to Barcelona, and Isabella set off with her two surviving children to meet him. Philip was by now tall enough and strong enough to ride a horse, but his intellectual development lagged: he still had not learned to read, and his principal exposure to written culture remained oral. He listened to The song of El Cid so often that he knew parts of it by heart: when one of his companions importuned him one day, Philip replied ‘You really annoy me, so-and-so; but tomorrow you will kiss my hand’, a rebuke clearly based on a passage from the medieval epic, in which King Alfonso tells El Cid

You really annoy me, Rodrigo; Rodrigo, you treat me badly,

But tomorrow you will swear allegiance, and then you will kiss my hand.10

Back in Spain, the emperor decided that his son – now aged seven – needed a tutor, and in 1534 he appointed Juan Martínez del Guijo, normally known by the Latinized version of his surname, Silíceo, a 48-year-old priest of humble origins who had studied at Paris and published books on philosophy and mathematics before becoming a professor of philosophy at the university of Salamanca. For the next five years, under Silíceo’s direction, the prince struggled to learn from the Short Grammar by Marineo Sículo (apparently the first book that he owned) and the devotional works of Ludolf of Saxony, known as ‘The Carthusian’.

In March 1535 Charles once more abandoned his son and left his wife pregnant: three months later, she gave birth to another daughter, Juana. Shortly afterwards Charles decided to remove the prince from ‘the control of women’ and created a separate household for him, headed by Don Juan de Zúñiga y Avellaneda, a ‘Philippist’ who had served him for almost thirty years. Significantly, Charles declared that he wanted his son to be raised in the same way as his uncle, Prince Juan of Trastámara, son and heir of Ferdinand and Isabella. The creation of a separate household in 1535 meant that henceforth Philip’s entourage would include only male servants (the emperor appointed about forty of them) and that Zúñiga (or his deputy) would sleep in his chamber at night and keep him under constant surveillance by day. ‘I am only absent’, Zúñiga assured Charles, ‘when I write to Your Majesty’ or when his charge was ‘at school, or somewhere with his mother that I am not allowed to enter’.11 Philip’s world would never be the same.

Prince of Spain

Don Juan’s absence when the prince was ‘at school’ reflected the Castilian tradition that ‘a prince should have two people to instruct him in different matters: a tutor [maestro] to teach him letters and good manners, and a governor [ayo] to impart military and courtly exercises’.12 Silíceo therefore had sole charge of teaching the prince and his principal pages how to read, write and pray; but progress was slow. By November 1535, Charles learned that ‘two months have passed without any reading or writing’ because the prince had been ill; while three months later Silíceo announced that he had again suspended the prince’s study of Latin for some days ‘because starting is so difficult’: small wonder that at age thirteen the prince ‘has only just started to write Latin’.13

By contrast, Philip showed precocious religious devotion. The stern and godly Zúñiga noted that ‘the fear of God comes so naturally to the prince that I have seen nothing like it in someone of his age’; but, he continued, the prince ‘learns much better after he leaves school’ – adding mischievously ‘and in this he somewhat resembles his father at the same age’. The frequent purchases of crossbows, arrows and javelins by his household treasurer testify to Philip’s growing ability to slaughter animals in the royal parks, and eventually Charles had to establish a weekly quota of each species that Philip was allowed to kill.14 To make up for this disappointment, the prince’s valet received ‘thirty ducats every month with which to buy things that please His Highness’. These included ‘a silver knight with full armour, and a silver horse for the said knight’; ‘a small bronze artillery piece, mounted on a carriage’; and ‘six very small gilded artillery pieces’. These items were all supposed to develop the young prince’s martial spirit. Other items were simply ‘for His Highness to enjoy’, such as ‘a bell from America with a sweet sound’. Philip also owned a deck of cards with which he and Zúñiga’s oldest son, Don Luis de Requesens, ‘spent a whole day building a church made of cards’. He also liked caged birds, some of them deliberately blinded because sightless birds were thought to sing better, and one of the earliest surviving images of the young prince shows him playing with a bird controlled by a cord (see plate 2). He later acquired other pets, including a dog that slept in his bedroom, a monkey, six guinea pigs and a parakeet.15

Philip also learned how to behave appropriately in public. He danced with his sister and he marched in the processions that preceded bullfights and tournaments, and in 1535, for the first time, he appeared in public in armour at the opening ceremony for a joust. The emperor was seldom present at these events. He left Spain in March 1535 and only returned in January 1537; afterwards, as soon as the empress had conceived again, Charles left for Aragon and the empress gave birth alone to another boy, named Juan (after Charles’s Trastámara uncle). He, too, died soon afterwards. This brought the emperor hurrying back to Spain – perhaps concerned that his wife was approaching the end of her fertility when he still only had one heir – and soon Isabella became pregnant for the fifth time. Once again, she miscarried. A painting in March 1539 shows the royal family, intently watching a tournament together, but their happiness would not last: the empress gave birth to another stillborn infant, fell ill and died on 1 May 1539, three weeks before Prince Philip’s twelfth birthday (see plate 3).

Philip never forgot the years spent with his mother. When in 1570 the majordomo of his new wife, Anne of Austria, asked what protocol her household should follow, the king answered curtly ‘let everything be the same as in the time of my mother’; and when specific questions arose, he again referred to ‘what I remember happened in the time of my mother’. Philip also remembered events and people from his early years. One day in 1594, at the age of 67, memories from those years overwhelmed him as he read a letter proposing candidates for the post of Inquisitor-General. When Cardinal Juan de Tavera got the post, Philip mused, ‘he had been archbishop of Toledo since the year 1534, when don Alonso de Fonseca died. I also knew him, and saw him the night before he died: we had just arrived at Alcalá de Henares, and he died that night’. The king went on to recall his first meeting with the father of one of the candidates, ‘which was early in the year 1533, with my lady the empress, who is in glory, when we went to Barcelona to await the arrival of the emperor’. He added: ‘I turned six in Barcelona that year.’16

Father and son, 1539–43

Upon the death of his wife, the emperor retired to a monastery for seven weeks to grieve, and he ordered both his daughters to move to the town of Arévalo, where they could grow up away from the bustle of the court – and away from their brother. Philip therefore presided alone at the funeral obsequies for his mother, held in the church of San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo. It was his first appearance on the public stage as a solo actor.

When he emerged from his monastic retreat, Charles resolved to take personal charge of grooming his heir and to this end he significantly increased the size of Philip’s household, appointing Zúñiga as its majordomo (while remaining the prince’s governor); but almost at once, news arrived of a tax revolt in the Netherlands. This presented Charles and his advisers with an agonizing dilemma, because the taxpayers of Castile also seemed restless. In 1538 the nobles assembled in the Cortes of Castile refused to vote any more funds for the emperor’s wars, and he dismissed them with angry reproaches. Leaving Spain therefore represented a major risk: everyone remembered that the last time Charles left without naming a regent of the blood royal, the Comuneros revolt almost cost him his throne. Now, without the empress, he lacked any adult relative who could govern Spain; but he dared not stay because, according to his regent in the Netherlands, ‘what is at stake here is whether Your Majesty will be master or servant’.17

In November 1539 Charles departed for the Netherlands, leaving Philip as his nominal regent but with executive power invested in Cardinal Tavera, primate of Spain and Inquisitor-General, assisted by Francisco de Los Cobos, the de facto head of Castile’s administrative and financial bureaucracy, whom Charles appointed as Philip’s secretary. Just before he left Spain, Charles prepared two sets of Instructions. Those addressed to his ministers concentrated on their administrative duties and responsibilities (both towards the emperor and towards each other), while the document for Philip dealt with policy. The emperor composed it so that, in case ‘God may choose to call me’ before he had achieved his policy goals, ‘the said prince will know our intentions’ and follow the correct religious, dynastic and political strategies ‘so he can live and reign in peace and prosperity’. It was the first of many detailed papers of advice that would decisively shape the prince’s political outlook. Philip would follow the goals set out by his father for the rest of his life.18

After enjoining the prince to love God and defend His Church, the emperor urged him to place his trust above all in his relatives.

Create and continue a true, sincere and perfect friendship and understanding with the king of the Romans, our brother [Ferdinand], and with his children, our nieces and nephews; with the Queens of France [his sister Eleanor] and Hungary [his sister Mary]; with the king and queen of Portugal [his sister Catherine], and their children, and with the said king’s brother, as you are obliged to do through your family ties, and continue the friendship and understanding that exist between them and me.

Charles next considered how best to deal with three contentious issues: France, the Netherlands and Milan. He saw them as linked, because although he was currently at peace with the king of France, this would continue only if the parties agreed ‘to end and extinguish all quarrels and conflicts of interest’ concerning the Netherlands and Milan and sealed the deal with ‘marriage alliances’. The emperor revealed that he had promised King Francis that his second son would marry the Infanta María, with Milan as the dowry. In spite of this promise, however, both Charles and the empress had stipulated in their testaments that ‘if we should have no other son than the prince, as has occurred’, then María would marry a son of Charles’s brother Ferdinand, and that together they would rule the Netherlands. This issue had become critically important with the ‘unrest and rebellion’ in the Low Countries. The emperor feared that ‘the diversity of its inhabitants and the multitude of sects opposed to our holy faith and Church, established under the pretence of liberty and self-government, may cause not only their total loss and separation from our House, but also their alienation from our holy faith and Church’. He therefore proposed to renege on his previous undertakings to both Francis and Ferdinand, so that ‘the prince our son shall inherit the Netherlands’ – but, he warned Philip, since this outcome involved serious risks, he might after all decide to ‘bequeath the said Netherlands to our daughter [María] and her future spouse, in order to avoid the said risks, to benefit Christendom and our son, and to assure the well-being, security and tranquillity of the kingdoms and other territories that he will inherit’.

The emperor’s Instructions also laid out the policy Philip must follow towards three other states: Portugal, Savoy and England. The Infanta Juana must marry the heir to the Portuguese throne, Prince John; the French must evacuate Savoy, seized from Charles’s brother-in-law the duke; and Philip must ‘take great care not to agree carelessly to anything that might adversely affect our faith and Church’ in England by allowing the Protestants to make gains. Moreover, family ties also obliged the prince ‘to watch over’ his cousin Mary Tudor ‘and to assist and advance her cause as much as may conveniently be done’.

This remarkable document, laying bare secrets that Charles had revealed to no one else, testifies to great confidence in his heir; but since Philip was too young to implement any of its policies, we must wonder about the intended audience. Since the surviving Instructions to Tavera contain nothing about foreign policy, and since the document addressed to Philip contains nothing about keeping it secret (as the emperor’s later Instructions would do), no doubt Charles intended his son to share it with Tavera, Cobos and Zúñiga. If Charles should die abroad, this triumvirate would guide all the prince’s dealings.

Although these Instructions never took effect (because Charles survived), they identified several issues that would dominate Spanish foreign policy for the rest of the century: the paramount need to maintain good relations with the Austrian branch of the family, and to intermarry with the Portuguese royal family; the possibility that either Milan or the Netherlands might need to be abandoned; the responsibility to restore Savoy to its duke; and the obligation to protect the Catholic faith, and the Catholic claimant to the throne, in England. In addition, the document exhibited three defects that would undermine Spanish foreign policy for a century: excessive secrecy, contempt for solemn promises and reluctance to surrender any territory. Charles’s Instructions of 1539 thus highlighted in striking fashion both the strengths and the weaknesses of the possessions that his only son would inherit.

For the next two years, Zúñiga had sole control of Philip’s upbringing, and his detailed reports to the emperor enable us to follow the prince’s progress. To begin with, his religious life changed radically. After his mother’s death, the prince turned his devotional attention increasingly to his namesake, St Philip, on whose feast day he became a knight of the Golden Fleece (1533) and recovered from smallpox (1536) – events which showed that the saint was ‘looking out’ for him. On that same day in 1539 his mother died, a coincidence that further reinforced Philip’s devotion to his patron, because it suggested that the saint had intervened to escort his mother to heaven. Henceforth he would combine celebration of his saint’s day with commemoration of his mother’s death. In 1541, Philip took his first communion, and Zúñiga proudly assured the emperor that ‘Your Majesty should thank Our Lord that he has a Christian son, who is also virtuous and intelligent.’ As an example of the former, Zúñiga noted that of the thirty ducats that Philip received each month ‘to buy things that please him’ he gave ‘fifteen to God’.19

The prince also excelled at outdoor exercises. In 1541 he began to go hawking, and Zúñiga reported that ‘although he greatly enjoys shooting his crossbow, when he cannot do that he enjoys hawking – and indeed any outdoors activity’. Philip also learned how to fight. His household treasurer bought ‘two fencing swords’ and ‘four lances so that His Highness could run at the ring’, and by 1543 Zúñiga declared that ‘His Highness is the best swordsman in this court’, adding a little later ‘he fights very well on foot and on horseback’.20

Zúñiga remained less enthusiastic about the prince’s studies. In June 1541 he noted that ‘for the past two months, I have been more optimistic than I used to be that he will like Latin, which pleases me very much because I believe being a good Latinist is an important part of being a good ruler, for knowing how to govern oneself and others’, – but that precise modifier ‘two months’ was not accidental.21 At Zúñiga’s suggestion, earlier that year Charles removed Silíceo as his son’s tutor and appointed the Aragonese humanist Juan Cristóbal Calvete de Estrella, ‘a very learned man’ who was ‘of pure blood’ (that is, without any Jewish or Moorish ancestors), ‘as master of grammar to teach all the present and future pages of the prince’. The new instructor immediately exposed his young charges to the best scholarship available.22

Although Silíceo despised humanism, he had not entirely shielded Philip from its influence. For example in January 1540, during a visit to Alcalá de Henares to hunt, Cardinal Tavera decreed that the prince should visit the Complutense University and for three hours Philip toured the classrooms, listening to lecturers in Latin, and sitting in the audience while a bachelor of theology graduated. But full exposure to the new learning began only when Calvete took over, soon assisted by three other instructors: Honorato Juan to teach him mathematics and architecture; Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda to teach him history and geography; and Francisco de Vargas Mexía to teach him theology. All four preceptors had travelled extensively outside Spain and boasted a cosmopolitan outlook that would broaden the prince’s horizons.

From the first, Calvete implemented a clear pedagogical vision. In 1541, he purchased 140 books, and had them specially bound for the prince, more than doubling the size of his library. Almost all these works were written in Latin, either by classical authors (such as Caesar, Cicero, Plautus, Seneca, Terence, Vergil) or by modern humanists including Erasmus (Adages and Enchiridion), Juan Luis Vives (Of the soul and life) and – surprisingly – Philip Melanchthon, Luther’s principal lieutenant (On the art of speaking). Moreover, although works in Latin predominated, Philip became the first Spanish monarch to read Greek (he could eventually manage works by Homer in the original) and he also learned some Hebrew and Aramaic so that he could study the Bible in its original languages. He acquired an Arabic grammar and ‘a book about the Qu’ran that His Highness ordered to be bought’.23 Philip acquired the last item during a visit to Valencia in 1542, perhaps because Honorato Juan (a Valencian) thought it might help his pupil to understand his future Morisco subjects. The visit formed part of a Grand Tour during which the emperor took his heir to Navarre, Aragon and Catalonia as well as Valencia, to be recognized as ‘heir apparent’, and en route Calvete, Juan and Sepúlveda – all of whom accompanied Philip – seized every opportunity to provide instruction about the different languages, cultures and histories of his new vassals. Finally, when news arrived that the French had laid siege to Perpignan, the second city of Catalonia, Sepúlveda led a debate among courtiers on the best way to save it – Philip’s first exposure to military strategy.

When the court returned to Castile, Calvete purchased more books in Latin to support his ambitious pedagogic strategy. Works of history – written by classical and medieval authors as well as modern humanists – constituted the largest single category (25 per cent of all books purchased between 1535 and 1545), closely followed by theology (15 per cent of the total), but most disciplines were represented. As he and his pupil finished each volume, Calvete seems to have added a ‘hashtag’ (#) before moving on, and by the time his formal education ceased in 1545, Philip had studied several hundred books on a wide variety of topics. Calvete also exposed the prince to learning in other ways. Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas, who had lived in America for decades, presented him with a dedicated manuscript copy of his Very brief account of the destruction of America; and during a visit to Salamanca in 1543, aged sixteen, he spent his first afternoon ‘inspecting the classrooms and hearing some lectures’ by a university professor. The following day ‘His Highness listened to all the other professors and attended an oral examination in Law … He left very late.’24

3. Books acquired by Philip, 1535–47. Prince Philip’s household treasurer recorded the title and date of purchase of every book acquired by or for his master, and the pace of purchases reveal the immediate impact of the advent of Juan Cristóbal Calvete de Estrella as the prince’s principal tutor late in 1540.

Calvete’s pedagogic plan nevertheless left considerable gaps. The prince’s library boasted few books on either law or warfare, and even fewer in any modern language except Spanish. Moreover, Philip received no formal instruction in French, Italian or any of the other languages spoken by his subjects, an important lacuna that reflected a deliberate choice: since Latin was a universal language, Zúñiga believed, ‘it is useful to know one language well and thus avoid having to learn them all’. The emperor agreed: ‘See how many territories you must rule, and how many components there are, and how distant they are from one another, speaking so many languages,’ he reminded his son in 1543. Therefore,

You must understand them and be understood by them, and to that end nothing could be more necessary or universal than the Latin language. That is why I strongly encourage you to work to learn it so that later on you are not afraid to speak it fluently. It would do you no harm to know some French too, but I would not want you to abandon one in order to study the other.25

As a result, Philip never entirely mastered French. He rarely spoke it, and when in 1576 the French ambassador read out a letter from his king, Philip later confessed to a minister ‘to tell the truth, I understood little of it’ because ‘I do not understand French well’.26 Conversely, Philip’s broad and deep exposure to humanist learning explains not only his facility with Latin but also his forceful style when writing Spanish, as well as his self-confidence (not to say arrogance) when discussing almost every aspect of intellectual endeavour: architecture with architects, geography and history with ministers and academics, and even theology with popes.

The adolescent prince took part in more complex recreations than before. His household accounts record the purchase of chess sets, playing cards and ‘gloves to play pelota [an early form of tennis]’. He also enjoyed the humour of fools and jesters: between 1537 and 1540, the prince’s treasurer made several payments to ‘Jerónimo the Turk’, the prince’s first jester, and in 1542 he bought two candles ‘to replace the two in His Highness’s chamber that Perico the Fool broke in pieces’.27 Philip also enjoyed music. His chapel included a choir consisting of two trebles, two countertenors, two tenors, four counter-basses and two organists; and in 1540 he had the organs in his chapel repaired and always took them with him on his travels. The compositions and performances of Antonio Cabezón delighted the prince so much that he took the blind organist with him to northern Europe in 1548–51. He also employed the composer Luis de Narváez, who taught him and his sisters to play the vihuela.28 Philip’s household included a dancing master, who taught all the royal children, and a painter who instructed the prince as he filled ‘a book of large sheets which His Highness requested for his paintings’. Some early paintings have survived in the margins of one of Philip’s own books, probably done in 1540–1 – the same time that he acquired his ‘book of large sheets’ (see plate 4).29 Thanks to these various activities, the cost of the prince’s household almost doubled between 1540 and 1543, by which time it numbered some 240 persons, and it required 27 mules and six carts to transport his possessions whenever Philip moved between the royal residences in Madrid, Toledo, Aranjuez, Segovia and Valladolid.

Everywhere Philip went, he was now preceded by his personal standard, a mark of the elevated status that distinguished him from others at court, and he sported his own coat of arms and his own seal (prominently displayed on the rich leather bindings of his books). He had his own motto: Nec spe nec metu (‘With neither hope nor fear’). In March 1541, he donned armour for the first time and ‘ran at the ring’ at the head of a team of five knights ‘wearing a mask, and although many others competed, he won the prize outright’. Five months later, Zúñiga reported, ‘His Highness is doing very well, and with great desire (if he receives permission) to serve with his father’ on the emperor’s amphibious expedition against Algiers (‘permission’ that Charles denied).30 Three months later, the emperor announced that his son would marry Princess María Manuela of Portugal, the daughter of Charles’s sister and Isabella’s brother, and so Philip’s first cousin on both sides of the family.

The prince had been thinking about procreation since he was a boy of eight: when Doña Estefania de Requesens, the wife of his governor, gave birth to a daughter, Philip told her that he wanted all her daughters ‘to become ladies-in-waiting to his wife’.31 After the death of the empress, Charles began to spend more time with his son, instructing him in the art of government both as they toured the crown of Aragon and after their return to Madrid. The emperor no doubt intended to make these lessons a regular fixture, but when Francis I declared war on him again in 1543 Charles left Spain to take personal charge of operations. This time, unlike in 1539, he overrode the laws of the kingdom (which forbade anyone under the age of 20 to rule):

By virtue of our own certain knowledge, will, and absolute royal authority, which in this matter we wish to use and do use as king and sovereign lord, not recognizing any temporal superior, we choose and select, constitute and nominate Prince Philip to be our lieutenant general and governor of our kingdoms and lordships [of Spain].32

The threshold of power

Because he would not be able to provide any more lessons in person, just before he left Spain Charles wrote three sets of Instructions to assist his son to discharge his arduous new responsibilities. A ‘General Instruction’, dated 1 May 1543, listed Philip’s powers and duties as governor of Castile. It required him to perform some of his devotions in public; to ‘take his meals in public; to reserve some hours of the day to hear those who come to speak to him; and to receive the petitions and memorials that they give him’. It also stipulated that the prince must only take decisions with the approval of a triumvirate composed of Tavera, Cobos and Fernando de Valdés, president of the council of Castile. That same day, the emperor signed another document entitled ‘Restrictions on the powers of the prince’, which listed numerous matters which Philip could not decide, despite the apparently full powers conceded in the General Instruction. Most of them related to the royal patronage – ‘you must not issue certificates legitimizing the children of clerics’; ‘I reserve for myself matters arising from ecclesiastical vacancies’ – but some were broader: ‘Do not promise rewards, because I do not do so’; ‘Do not grant anyone jurisdiction over native Americans without my express permission’.33

On 4 May Charles prepared more personal Instructions for his son, writing out in his own hand ‘what I know and understand about how you must comport yourself in governing these kingdoms’. The emperor began by noting that ‘although you are very young for such a demanding position, there have nevertheless been people no older than you whose courage, virtue and good judgment were such that their deeds surpassed their scant years and experience’. He continued:

Above all else you must be resolute in two things. First and most important: always keep your eyes on God, and submit to Him all the tasks and concerns that face you, and sacrifice yourself. Be very ready to do this. Second: believe and accept all good advice. These two resolutions will enable you to overcome your lack of maturity and experience, and you will undertake things in such a way that you will soon be capable and experienced enough to govern well and wisely.

Charles then provided a series of specific injunctions. ‘Never order justice to be done if you feel anger or partiality, especially in criminal matters.’ ‘Avoid being angry and never do anything in anger.’ ‘Be very careful not to promise anything, either orally or in writing, or to raise expectations for the future.’ ‘Grant audiences when required, and be affable in your answers and patient when listening; and appoint fixed hours during which people can see and talk to you.’34

The emperor next turned to personal matters, and his tone became sharper. ‘You need to change your way of life and your relations with other people,’ he bluntly stated. ‘As I told you in Madrid’ (an allusion to earlier intimate conversations between father and son),

you should not think that your studies will prolong your childhood. Instead, they will make you grow in honour and reputation so that, despite your youth, you will be taken for a man. Becoming a man early is not a matter of thinking or desiring it, or of being fully grown, but solely of having the judgment and knowledge necessary to act as a man, and as a wise, sane, good and honourable man. For this to happen, everyone needs education, good examples and discourses.

‘Until now,’ the emperor continued relentlessly,

your only companions have been children and your pleasures have been those enjoyed in their company. From now on, you must only keep these people around you in order to tell them how they are to serve you. Your principal company must be that of older and mature men who have virtues, good conversation and deportment; and let the recreation you take be with such people and in moderation, because God created you to rule and not to relax.

In particular, Charles chided his son for ‘spending so much time with jesters’ and ordered him to ‘pay less attention to Fools’ (a counsel that Philip either could not or would not obey).

Finally, the emperor turned to the subject of sex. ‘You will soon be married’ and, Charles warned,

Inasmuch as you are of young and tender age and I have no other son, and I do not wish to have others, it is very important that you restrain your desires and do not make excessive efforts at this early stage, which could lead to physical damage, because apart from the fact that it can be dangerous both for the body’s growth and for its strength, it can often lead to such weakness that it interferes with conceiving children and even causes death, as it did with Prince Juan [of Trastámara], which was how I came to inherit these kingdoms.

The emperor shared the common (but erroneous) belief that the heir of Ferdinand and Isabella, who in all other respects should serve as Philip’s role model, had died as a result of immoderate sexual activity with his young wife; and he had no intention of letting Philip follow suit. Charles had evidently established that his son was still a virgin and also extracted a promise from him to remain that way: ‘I am certain that you have told me the truth about the past, and that you have kept your word to me [to be celibate] until you are married’. Now he demanded that the prince show equal moderation after his marriage.

You must be very restrained when you are in your wife’s company, and since that is somewhat difficult, the solution is to keep you away from her as much as possible; and so I require and request that once you have consummated the marriage, you plead some illness and keep away from her and do not visit her again so quickly or so often. And when you do return, let it be for only a short while.

Charles backed up this remarkable demand by instructing his ministers to compel the young couple’s compliance.

In order to make certain there are no shortcomings in this matter, although from now on you no longer need a tutor, in this matter alone I want Don Juan [de Zúñiga] to continue [in this capacity.] According to what I told you in his presence, in this matter you must do only what he tells you. By these instructions, even though it may anger you, I order him not to refrain from saying and doing all he can to see that you comply.

To make absolutely sure that his son would obey, Charles also ordered the duke of Gandía (the future St Francis Borgia) to keep his son’s future wife ‘away from you except for the times when your life and health can stand it’. It is hard to imagine a situation more likely to create a serious complex about sex in a fifteen-year-old boy.

On 12 November 1543, dressed ‘entirely in white, so that he looked like a dove’, Philip met his bride-to-be and for some hours they danced and dined; afterwards they rested until 4 a.m. when Tavera married them; and only then did they retire to the princess’s chamber. But not for long: ‘after being together for two and a half hours Don Juan de Zúñiga entered the room and hauled the prince off to another bed in his own chamber’. Moreover, after less than a week of carefully rationed time together, the couple travelled to their separate beds in Valladolid where, ‘after a few days of sleeping apart, His Highness developed a most painful rash’. Zúñiga oscillated between relief that this meant ‘he will not be sleeping with his wife’ and concern that ‘the rash continues, and it is something he has never had in his life’. After his rash abated, Philip showed coolness – some said aversion – towards his bride: ‘When they are together, His Highness makes it seem as if he is there against his will, and as soon as she sits down, he gets up again and leaves’.35 Both Charles and Zúñiga reproached the prince about this: it never seems to have occurred to them that the humiliating regime they had imposed made María Manuela seem like a lethal weapon to her young husband.

Charles increased his son’s embarrassment even further by the way he communicated his 4 May instructions: ‘Don Juan de Zúñiga will present this document to you. Read it in his presence so that he can remind you of its contents whenever he deems it necessary.’ The emperor also suggested that his son might show the document to Silíceo, whose judgement and experience he extolled. It seems unlikely that Charles insisted on this procedure simply to humiliate his son (although that would have been the inevitable outcome); rather it was meant to deceive the two ministers named into thinking that he had opened his heart to them, as well as to Philip. In fact Charles had much more information to impart, and on 6 May he signed a further holograph letter to his son: ‘I am writing and sending you this secret document which will be for you alone. You must therefore keep it secret, under lock and key where neither your wife nor any other living person can see it’. It was the most remarkable piece of political advice ever committed to paper by an early modern ruler.

This time Charles began with an apology: ‘I am so sorry to have placed the kingdoms and dominions that I will bequeath to you in such extreme need’. Worse, if he died, ‘my finances will be in such a state that you will encounter many problems because you will see how small and encumbered my revenues are just now’. Nevetheless, the emperor added defiantly, ‘Bear in mind that what I have done has been necessary to safeguard my honour, because without that I would be less able to sustain myself, and I would have less to leave you.’ Philip’s first secret lesson from his father was that ‘honour and reputation’ were far more important than money: if he should lose his life in their defence, Charles declared grandiloquently, ‘I will have the satisfaction of having lost it while doing my duty and helping you’. Next, the emperor shared the military strategy he intended to follow against France and its allies, and where he planned to find the troops and treasure to put it into effect – once again so that his son would know what to do ‘if I should either be taken prisoner or detained on this journey’.36

Charles recognized that political affairs ‘are so confused and uncertain that I do not know how to express them’, because ‘they are full of confusion and contradictions, either because of the state of affairs or because of conscience’. Therefore, in all matters of policy, Philip should ‘always hold on to what is most certain, which is God’. Next came a most remarkable passage, preceded by another injunction that it ‘must be for you alone and you must keep it very secret’: a searing analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of each of the ministers on whose opinions the prince would have to rely ‘if God should call me to Him during this journey’.

The emperor again referred his son to ‘what I told you in Madrid’ about ‘the animosities, alliances and almost cabals that were forming or had already been formed among my ministers’ – but now he provided more detail because although each of his senior ministers ‘is the leader of a faction, I still want them to work together so that you will not fall into the hands of any one of them’. Therefore, Charles insisted, ‘do not place yourself, now or ever, in the hands of any individual. Always discuss your affairs with many, and do not become tied or obliged to any of them, because while it will save you time it is not in your interest.’ He then reviewed the strengths and weaknesses of each councillor in turn, starting with Don Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, duke of Alba. Although the emperor considered Alba ‘the best we currently have in these kingdoms’ when it came to military and diplomatic matters, he had deliberately excluded him from the prince’s committee of advisers:

It is best not to involve grandees in the government of the kingdom, and so I did not want to include the duke, which has left him not a little aggrieved. Ever since I have known him, I have found that he has great aspirations and seeks to become as powerful as possible, even though at first he came on the scene genuflecting, all humble and modest; so just think how he will behave around you, my son, because you are younger. You must avoid involving him or other grandees in the inner circles of government because they will try to take advantage of you by any means they can, and that will cost you a great deal later on.

Philip followed this advice throughout his reign: he never admitted Alba or any other grandee to ‘the inner circles of government’.

The emperor next evaluated the other ministers to whose care he had entrusted the prince. Cobos ‘does not work as hard as he used to do’, Charles complained, but nevertheless, ‘he has experience of all my affairs and is very knowledgeable about them’ so that ‘you would do well to deal with him as I do, never alone and not giving him more authority than is contained in his Instructions’. The emperor devoted several pages to Cobos, including some detailed suggestions on how to ‘manage’ him – how to reward him yet still keep him hungry for more – before turning to Zúñiga. Although he ‘may seem somewhat harsh to you’, Charles advised his son, ‘do not hold it against him’.

You must realize that since all the people who have surrounded you in the past and who currently surround you are indulgent and want to please you, this may make Don Juan seem harsh; but if he had been like the others, everything would always have been the way you wanted, and that is not good for anyone, not even older people, let alone youths without the knowledge or self-control that come with age and experience.

And yet, the emperor continued, no one was perfect. ‘I have two concerns about Don Juan. One is that he is somewhat biased, mainly against Cobos but also against the duke of Alba … His other fault is this: he is somewhat greedy.’ Nevertheless, the emperor concluded, ‘you will not find anyone who can advise you better, and more to my liking that these two’: Cobos and Zúñiga.

Charles was far more critical of the other ministers who would advise his son. For example, contradicting what he had written two days before, he now had little good to say about Silíceo: ‘We all know him to be a good man; but he was certainly not – nor is he now – the most suitable person for your education, because he has been too anxious to please you.’ Now, he is ‘your confessor, and it would not be good if he wanted to indulge you in matters of conscience as he has done in your education. So far there have been no problems,’ Charles continued, ‘but from now on there could be some very considerable ones.’ The emperor therefore recommended that his son ‘should appoint a good friar to be your confessor’.

Charles’s holograph instructions – so direct, so personal, so perceptive – made a tremendous impression on his son. ‘I remember a lesson that His Majesty [Charles] taught me very many years ago,’ he explained to a councillor in 1559, when he refused to promise future promotion to a supplicant, ‘and things have gone well for me when I followed it and very badly when I did not’ – a clear reference to Charles’s advice sixteen years before: ‘Be very careful not to promise anything, either orally or in writing, or to raise expectations for the future.’ In 1560, when interrogated by the Inquisition, he explicitly cited ‘the instructions that my lord the emperor, who is in glory, gave me when he left these realms in 1543, in which (among other things) he ordered me to make sure that prelates resided in their dioceses’. Again, in 1574, when Philip thought he might leave Spain and leave his wife as regent, one of his ministers suggested basing his Instructions for her on those Philip had drawn up when he had left for England twenty years before; but the king preferred ‘those from the time when I began to govern, in the year 1543’ because ‘the papers of advice that the emperor gave me then, written in his own hand’ contained so much useful information.37

‘His Highness received the Instructions that Your Majesty sent him,’ Zúñiga reported to the emperor in June 1543, ‘and has begun to follow them with great care and diligence in everything he needs to do’; while Tavera assured his master that ‘the prince has begun to exercise the powers that Your Majesty sent him, and in what we have seen so far he shows far more care and expertise in public affairs than one would expect of someone his age’. Although Charles had intended his son to sign in his own name only ‘the orders and warrants that concern his own household’, Zúñiga discovered ‘that Prince Juan [of Trastámara], when he dealt with his estates and when he signed other documents, wrote Yo, el príncipe [“I the prince”]’, and he showed Cobos ‘many documents signed by Prince Juan’ to demonstrate ‘that this was the normal style of the princes of Castile’. Without waiting for imperial approval, the two ministers resolved that Philip ‘should henceforth do the same’.38 ‘Felipito’ had come of age.