The changing face of empire, 1551–1558

Nemesis

PRINCE Philip returned to govern Spain in 1551 with far more experience and authority than before. When one of Charles’s nominees to represent him at the council of Trent declined to go, Philip casually informed his father ‘we have given some thought to a replacement, and Your Majesty will be advised of our decision’; and when demands for more troops and treasure arrived from his father, the prince first procrastinated and then refused on the ground that ‘everything here [in Spain] is exhausted’. He even reproached the emperor for wasting money: ‘I beg Your Majesty most humbly to put your affairs in order so that you can reduce expenses, because we have no manner or means to meet them.’ This shift in the balance of power did not go unnoticed. As a Spanish courtier wrote crudely to Philip in 1552: ‘I beg your Highness to authorize a response to the memorial that I gave you in Madrid, because we all know that you can transact all affairs of state without awaiting permission from [the emperor in] Germany’.1

The prince spent most of the winter of 1551–2 in Madrid, which he already seems to have preferred to Valladolid as his administrative base, negotiating with the Cortes of Castile for funds to defend Spain and Spanish Italy. But in April 1552 Henry II invaded Lorraine and seized three Imperial Free Cities (Metz, Toul and Verdun) while a Protestant army challenged Charles’s authority in Germany. Ferdinand and Maximilian, alienated by the emperor’s bullying at Augsburg the previous year, declared themselves neutral, leaving Charles dangerously isolated and without troops and money. He desperately appealed to his son that ‘without losing an hour’ he should raise and send as many Spanish troops as possible. ‘And above all,’ he added, ‘take special care to raise money, because you can see and appreciate how it affects our honour and reputation, and the retention of the dominions that God has given us and that we have acquired’ (an unsubtle reference to the fact that whatever Charles lost, Philip would lose too).2

The emperor’s appeal seems to have stunned (and perhaps shamed) the prince. ‘Since these revolutions have made Your Majesty need Spanish troops for what you have to do,’ he wrote, he would now raise the men and money that he had so recently claimed could not be found. He dispatched Alba to lead troops from Spain to the emperor’s rescue; and, as he had done in 1541 during the Algiers campaign (chapter 1), he begged for permission to join his father in his moment of need. ‘I want to be there in order to serve Your Majesty in this campaign,’ he pleaded, and he ordered the galleys carrying Alba’s troops to return to Spain at once so that they could transport him too, ‘because it does not seem right, nor does it redound to my honour, to abandon Your Majesty at this time.’3

While he awaited Charles’s answer, Philip said farewell to his sister Juana before she left to marry their cousin Prince John, heir to the Portuguese throne; then he travelled to Aragon to be closer to the Mediterranean coast when permission arrived for him to join his father. He soon found himself ‘in greater confusion than anyone has ever been, because I have been so long without a letter from His Majesty, and without orders on what I must do’; and when one eventually arrived, while praising his spirit and support, Charles forbade his son to leave Spain. Philip’s contribution would be to raise and dispatch the funds needed to sustain Alba’s army while it recaptured Metz, the largest of the three Imperial cities in Lorraine seized by France.4

Although at one point Charles and Alba commanded 55,000 men – perhaps the largest concentration of troops ever seen in sixteenth-century Europe – Metz held out. Just before Christmas 1552 the emperor decided he must abandon the siege, and he retreated to Brussels. There he suffered a physical and psychological collapse, refusing for three months to hold audiences, appear in public or sign documents. Mary of Hungary took charge of the Monarchy’s day-to-day affairs while Philip continued to administer Spain and Ferdinand ran Germany. This situation could not last, and in April 1553 (at Mary’s insistence) Charles summoned Philip back to Brussels – but on one condition:

Not only must you come here, but you must also bring with you such a large sum of money that it will serve to sustain these provinces adequately. This is the only remedy for the present situation, and the only way to ensure that … you will not be compelled, as soon as you arrive, to ask [the provinces] for new taxes which, since they are so exhausted, in addition to gaining you no affection, will rather cause them to resent twice as much (as subjects often do) the sacrifices you ask of them.

As soon as Philip arrived with the funds, Charles proposed to return to Spain ‘so that these provinces will not be left at a time like this without the presence of one of us’.5

This was totally unrealistic. As Philip reminded his father, Castile had just provided the unprecedented sum of over 4.5 million ducats for the defence of Italy, Spain and the Mediterranean, as well as for Charles’s rescue from his German enemies: the kingdom could provide no more now – especially since a joint French and Turkish fleet had just captured Corsica from its Genoese garrisons, jeopardizing communications between Spain and Italy. Without consulting his father, Philip at once sent 3,000 troops (and the money to sustain them) to regain Corsica, and authorized other defensive measures, further reducing the cash available for Charles.

The ‘English Match’

Almost immediately, the death of Edward VI, king of England and Ireland, on 6 July 1553 changed the diplomatic situation. After a few days of uncertainty Edward’s half-sister Mary Tudor, a 37-year-old spinster, ascended the throne and turned to her cousin Charles for advice. The emperor knew exactly how to exploit this windfall: he offered her the hand of his son. Charles carefully calculated the advantages to both parties. It would allow Philip to rule both Spain and the Netherlands effectively, even without becoming Holy Roman Emperor; and it would provide Mary with a ‘husband who could command in wartime and carry out other functions that are unsuitable for women’, perhaps allowing an invasion of Scotland that would ‘make it subject to the kingdom of England’. In addition, creating a new Anglo-Netherlands state to be ruled by the heir of Philip and Mary would secure Habsburg domination of the Channel and North Sea, and thus ‘keep the French in check and reduce them to reason’. Although Charles claimed unconvincingly that ‘I do not seek to do more than put this idea before you so you can think about it and tell me as soon as possible how it seems to you’, in effect the die had been cast: the advantages that the ‘English match’ would bring, Charles wrote, ‘are so great and so obvious’ that it was not necessary to explain them.6

Even with a kingdom as dowry, the prospect of marrying a cousin twelve years older left Philip unenthusiastic, but he accepted the inevitable. ‘Your Majesty already knows that, as your most obedient son, my wishes are the same as yours, especially in a matter of such importance,’ he wrote to Charles, and granted his father full powers ‘to negotiate on my behalf’ to secure ‘an English match’. Hard bargaining began on the terms between Mary and her Privy Council, on the one hand, and Charles’s envoys (led by Simon Renard and Count Lamoral of Egmont) on the other. The first stumbling block was whether the marriage would be finalized by proxies and take immediate effect, as Charles wanted, or whether (as the English preferred) ‘the wedding should be concluded and solemnized in the presence of both spouses’. Charles therefore demanded that his son send ‘two powers of attorney, drawn up like the attached minutes, so that we can use whichever one is needed without wasting any time’.7 Once again, the prince complied.

Charles and his advisers nevertheless concealed conditions added to the marriage treaty by Mary’s ministers to safeguard England’s independence: that the queen must not leave her hereditary realms except in exceptional circumstances; that any child of the couple would inherit not only England and Ireland but also the Netherlands; and that, if Mary should predecease her husband without leaving any heirs, Philip’s authority in England would end. Moreover, although the treaty specified that Philip ‘shall during the said marriage have and enjoy jointly together with the said most gracious queen his wife, the style, honour and kingly name of [her] realms’, and provide ‘aid’ to his wife in governing them, it went on to insist that ‘the said most noble prince shall permit and suffer the said most gracious queen his wife, to have the whole disposition of all the benefices and offices, lands, revenues and fruits of the said realms and dominions, and that they shall be bestowed upon such as shall be naturally born in the same’. Philip would not be able to ‘bestow’ any English assets on his subjects elsewhere. As if these restrictions were not humiliating enough for Philip, Mary’s advisers also stipulated ‘that the realm of England, by occasion of this matrimony, shall not directly or indirectly be entangled with the war that is betwixt the most victorious lord the emperor, father unto the said lord prince, and Henry, the French king; but he, the said lord Philip, as much as shall lie in him, on the behalf of the said realm of England, shall see the peace between the said realms of France and England observed, and shall give no cause of any breach.’8

Although the Imperial negotiators either omitted or minimized the significance of these developments in their letters to Philip, the prince knew all about them. On 4 January 1554, even before his father’s agents signed the original treaty, the prince executed before a notary a deed stating that he would ‘approve, authorize and swear to the said articles so that his marriage to the most serene queen of England may take place, but this does not bind or oblige him and his possessions, or his heirs and successors, to execute or approve any of them’.9 Such duplicity became central to Philip’s administrative style: when constrained to take actions that he disliked, he made a declaration before a notary that he did not regard concessions made under duress as binding.

Philip remained in Spain for another six months, despite warnings not only from his father but also from Mary of Hungary, who wrote ‘I can assure you that if these dominions in the Netherlands are not succoured, you will lose them’.10 The prince lingered in part because he lacked papal dispensation to marry a close relative (initially, Philip referred to his future bride as ‘my beloved and very dear aunt’, since her mother was the sister of Charles V’s mother), but at last permission arrived and in March 1554, with Philip’s permission, Egmont stood as his proxy beside Mary Tudor while England’s Lord Chancellor blessed the marriage.

Still the prince remained in Spain. Instead of travelling to Corunna, where a fleet waited to take him to England, he rode to the Portuguese frontier to meet his sister Juana, now a widow, whom he had persuaded to act as regent during his absence. As he had done with María and Maximilian, Philip provided her with detailed instructions in person on how she should act. He also accomplished another important task. He had received a confidential message from his father, asking that he choose his retirement home. Philip recommended Yuste, in the foothills of the Sierra de Gredos in Extremadura, site of a convent built by the Jeronimite Order, whose dedication to prayer had appealed in the past to members of Spain’s royal family who wanted to retire from the world. After visiting Yuste in June 1554, Philip signed warrants to cover the cost of building a modest palace complex adjacent to the monastery.

Now at last Philip moved to Corunna, and while he waited for a favourable wind to take him to England, he issued his final orders for the regency government. During his absence Juana and her ministers must send him copies of all correspondence with Charles and also consult him before taking any major decisions concerning Spain, Spanish Italy or Spanish America. Although his Instructions claimed to relay ‘the arrangements that His Majesty and I want’, they explicitly ignored or overrode his father’s earlier dispositions.11 Having thus secured his inheritance, with a fleet large enough to deter any attempt by the French to intercept him, on 13 July 1554 Philip left Spain to marry the queen of England.

‘I left Corunna on Friday,’ the prince wrote, ‘and that day I was so sea sick that I had to spend three days in my bed to recover.’12 Luckily for him, the entire voyage from Spain to England took only seven days (a happy circumstance that may have distorted Philip’s strategic thinking three decades later when he planned the invasion of England). He found both English and Netherlands envoys awaiting him at Southampton, where his fleet dropped anchor: the former brought him greetings and presents from his bride-to-be; the latter brought Charles’s renunciation of his title to Naples in favour of his son, who thus became a king in his own right on the eve of his wedding. It was a gracious gesture. Less gracious was the message that followed. Originally, Charles had intended his son to remain in England only long enough to consummate his marriage before coming to the Netherlands to take command, so that the emperor could return to Spain. Now, instead, Charles ordered Philip to send only the troops and treasure: he had decided to take personal command of his forces, once more relegating his son to an ancillary role.

England’s summer weather proved uncooperative: torrential rain soaked Philip and his entourage as they made their ceremonial entry into Winchester, where the betrothed couple had their first formal meeting. According to Juan de Barahona, a member of the royal entourage, ‘His Highness was very courteous with the queen for more than an hour, speaking to her in Spanish while she spoke French, which is how they understood each other.’ Then Philip spoke the only words of English he is known to have uttered: ‘Good night, my lordes all’. On 25 July, Philip and Mary were married in Winchester Cathedral and, after a banquet, the ‘dukes and nobles of Spain’ danced with ‘the most beautiful English virgins’ until 9 p.m., when ‘the king went to bed with the queen. And as for the rest of the night,’ wrote Barahona (probably with the same lack of enthusiasm as his master), ‘those who have endured the same can judge.’13

Her first sexual encounter left Mary exhausted and, according to Andrés Muñoz, Philip’s valet, ‘she did not appear in public again for four days’.14 While she recovered, her new husband went hunting and sightseeing with a large entourage that included not only established courtiers like Alba, Feria and Ruy Gómez but also a number of others who would soon rise to high office, including the duke of Medinaceli, the counts of Chinchón and Olivares, friars Bernardo de Fresneda and Bartolomé Carranza, and secretaries Pedro de Hoyo and Gabriel de Zayas. Few relished the experience: ‘Although we are in a beautiful country, we live among the worst people in the world,’ wrote Muñoz. ‘These English are great enemies of the Spanish nation.’15

What did Philip think of his new bride? ‘The queen is a very good creature,’ Ruy Gómez confided to a colleague the day after the wedding – ‘though rather older than we had been told.’ Later that week his attitude hardened: Philip ‘strives to give [Mary] every possible proof’ of his affection and ‘omits no part of his duty’, but ‘to speak frankly with you, it will take a great God to drink this cup’. Luckily, Ruy Gómez concluded, Philip ‘fully realizes that the marriage was not concluded for the sake of sex, but to remedy the disorders of this kingdom and to preserve the Low Countries’. Spanish opinion became harsher still after Mary’s death. In 1559, when Philip married again, a minister wrote unkindly that this time with young Isabel of France ‘His Majesty will have no cause to complain that he has been forced to marry an ugly old woman’.16

In November 1554 the queen asserted she had felt the ‘quickening’ of her child, and the following month she informed Charles that ‘as for that which I carry in my belly, I declare it to be alive’. The couple moved to Hampton Court ‘where it was thought the queen would give birth’ and there assembled midwives, a cradle ‘very sumptuously and gorgeously trimmed’ and a wet-nurse. Meanwhile chancery clerks prepared multiple documents announcing the birth that left only the date and the sex of the infant blank.17

Although Mary experienced many of the signs normally associated with pregnancy – swelling of the abdomen and breasts, milk secretion – she never gave birth, and the assembled cradles and nursery staff dispersed. Charles now urged his son to join him, and in late August Philip left his wife at the palace of Greenwich and boarded a waiting ship. As it moved slowly down the Thames, Philip stood ‘on the poop deck, and waved his hat to greet the queen and show his affection for her’, but his distraught wife sat by a window and cried her eyes out. The two monarchs exchanged letters ‘not only every day but every hour’ until 3 September, when Philip crossed the Channel.18

The new king nevertheless continued to provide ‘aid’ to his wife in governing their realms. Mary’s Privy Council had made this easier by issuing an order two days after the wedding that circumvented the restrictions imposed in the marriage treaty on Philip’s participation. Thenceforth ‘a note of all suche matters of state’ debated by the council was ‘made in Laten or Spanyshe’ to be ‘delivered to suche as it shuld please the kinges heighnes t[o] appoint to receyve it. It was also ordred that all matters of Estate passing in the King and Quenes names shuld be signed with both thier handes.’19 This meant that Philip, although unable to speak or understand English, could take an active role in English affairs; and after he left for the Netherlands he communicated his wishes in letters written in Latin or Spanish to Mary and her principal adviser, Cardinal Reginald Pole. Three days after Philip’s departure, Pole informed him that Mary took great pleasure ‘from writing to Your Majesty and reading his letters’ and in learning what ‘the king has devised and ordered’. Two weeks later, Pole reported that ‘the queen passes the forenoon in prayer, after the manner of Mary, and in the afternoon admirably personates Martha, by transacting business, so urging her councillors as to keep them all incessantly occupied … in following the course pointed out by’ her absent husband.20 The king also indicated his preferred ‘course’ through orders to a new administrative organ created just before his departure: the Select Council, composed of English ministers. This body met several times a week to discuss important domestic and foreign affairs, and at the end of each meeting it sent a Latin summary of its recommendations to Philip for comment. In most cases the king approved the recommendations, but sometimes in a marginal comment he raised objections. Thus in September 1555, the Select Council reported that most vessels in the Royal Navy were unseaworthy and should be brought to the Thames dockyards for repair, but Philip objected:

The king understands that England’s chief defence depends upon its navy being always in good order to serve for the defence of the kingdom against all invasion, and so it is right that the ships should not only be fit for sea, but instantly available. But, as the passage out of the river Thames is not an easy one, the vessels ought to be stationed at Portsmouth, from which they can more easily be brought into service.

The councillors duly complied.21

Philip helped to shape English policy through appointments to offices of state, assisted by the Spanish clerics who accompanied him on his voyage, above all Carranza. Thus upon the death of the Lord Chancellor, England’s most senior minister, Carranza suggested the appointment of the pious archbishop of York and Philip himself sent a letter instructing Mary ‘that the said office should be given to the said archbishop’, and it was done. English courtiers immediately recognized Philip’s decisive role in the outcome: ‘the king’s majesty hath appointed the bishop of York Lord Chancellor,’ one of them noted.22

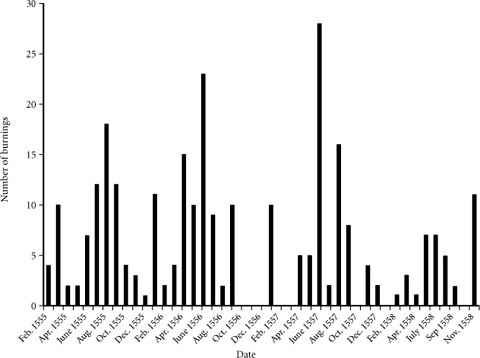

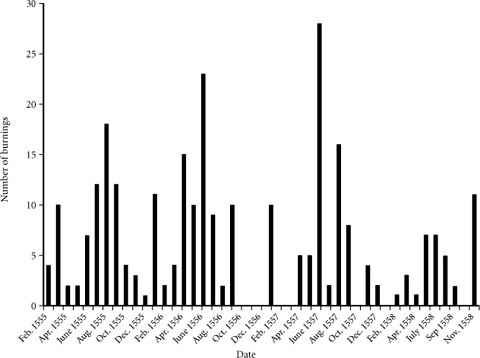

6. Executions for heresy by burning in England, 1555–8. At least 284 Protestants (56 of them women) were burned for their faith while Philip was king of England, starting in February 1555. Although the king’s presence in England does not seem to have affected the rhythm of executions, the Privy Council oversaw the policy and sent copies of their deliberations to Philip, so he could monitor the totals – right up to his last month as king of England.

Philip also took a keen interest in religious matters. According to Carranza, royal officials imprisoned and burned more than 450 English heretics between February 1555 and November 1558, while at least 600 more fled abroad. An eminent modern historian has suggested that Philip and Mary oversaw ‘the most intense religious persecution of its kind anywhere in sixteenth-century Europe’.23 Philip intervened openly in at least one heresy case. On Easter Day, 1555, William Flower, a married ex-monk, stabbed a Dominican friar while he was saying Mass. Outraged by such sacrilege, Carranza (now ‘vicar and commissary general’ of the Dominican Order in England) urged Philip and Mary

to order that exemplary justice be done immediately, saying that this was essential because any delay would cause a scandal. His Majesty promised to do this, and it was done within three days: they cut off the right hand with which he committed the crime and then burned him alive.

The king had no regrets. He later boasted that ‘many heretics had been burned and many others converted’ in England during his reign, including Thomas Cranmer, archbishop of Canterbury, burned at the stake in 1556.24

The transfer of power

Meanwhile, in May 1555, Gian Pietro Caraffa, an avowed enemy of Charles and his son, was elected Pope Paul IV and immediately laid plans for a coordinated attack with the assistance of France, the Turks and several sympathetic Italian states. This forced the Rey Príncipe (as Philip now styled himself: ‘the king and prince’) to take two pre-emptive steps. In the hope of winning the support of his Austrian relatives, he formally renounced all his claims to the Imperial title (chapter 2); and he took the reins of power from his father.

Charles’s efforts to defend the Netherlands in the summer of 1554 had left him exhausted, and as soon as the French withdrew he retired to a small cottage in the royal park in Brussels and refused to see anyone except a few trusted household servants. A sketch of the emperor at this time shows a broken man with no teeth or hair, whose hollow eyes stare vacantly into the distance (see plate 8). On 25 October 1555 Charles walked slowly into the great hall of his Brussels palace, supported by a cane on one side and by Prince William of Orange on the other, followed by Mary of Hungary and his son Philip.

The proceedings began with a speech by a councillor explaining the emp-eror’s reasons for wanting to abdicate and retire to Spain (mainly because ‘the intense cold greatly undermined’ his health). Then Charles rose unsteadily to his feet, ‘put on his glasses and read what was written on a piece of paper’ before making an eloquent and emotional speech reminding his audience of all the enterprises he had undertaken in their name. He then urged everyone to uphold the Catholic faith as the sole religion.25 After he had finished, Philip fell to his knees and (in Spanish) begged his father to stay and govern a little longer so that he might ‘learne of him by experience soich qualetyes as to soch a gouvernment are most necessary’; then he sat down again and, turning to the assembly, spoke the only words of French he is known to have uttered: ‘Gentlemen, although I can understand French adequately, I am not yet fluent enough to speak it to you. You will learn from the bishop of Arras [Granvelle] what I want to say.’ As in England, Philip’s failure to learn the languages of his subjects – and his decision to sit while addressing them, instead of standing as Burgundian protocol demanded – caused needless disappointment, but Granvelle offered some reassurance by promising, on Philip’s behalf, that the new ruler would stay in northern Europe as long as required to secure their peace and prosperity and that he would return whenever needed – a wise promise which the king would not keep.26

Despite all the pomp and emotion, the Brussels ceremony only marked the transfer of the emperor’s territories and titles in the Low Countries. Charles intended to travel back to Spain before ceding his rights over Castile and Aragon and their overseas dependencies (the Americas, Sardinia and Sicily), but lack of money to pay off his household and assemble a fleet prevented this; and so, while still in Brussels, in January 1556 Charles transferred his Spanish kingdoms, together with the title ‘Catholic King’, to his son – henceforth styled Philip II. At Ferdinand’s request, Charles also drew up and signed a secret renunciation of his Imperial title, leaving his brother to determine the optimal moment to convene a meeting of the Electoral College to choose his successor. Meanwhile, Charles appointed his son as Imperial Vicar (deputy) in Italy.

Right up to the moment when he signed each of these solemn transfers, Charles continued to issue orders and make appointments. For example, three days before the abdication ceremony in Brussels, Charles wickedly made a host of irrevocable appointments to ecclesiastical, military and civil posts in the Netherlands, thereby depriving his son of the chance to promote his own men. Father and son seem to have held proper consultations on only one matter: who should succeed Mary of Hungary as regent of the Netherlands – but although they agreed on Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy, for as long as the two monarchs remained in the Netherlands the creation of a third centre of power merely increased the confusion over who was in charge and how to allocate the sparse funds available for defence.

This situation was not sustainable. As the duke of Alba, charged with defending Spanish Italy, bluntly observed: ‘We need money or peace, one or the other, or everything will collapse.’27 In February 1556, lacking sufficient money to carry on fighting, Philip swallowed his pride and signed the truce of Vaucelles with Henry II of France. Since each side remained in possession of its conquests no one expected the ceasefire to last long, and Philip therefore resolved to remain in Brussels while his father set sail for Spain, where Philip expected him to take an active role in government; but the emperor had other plans. He headed straight for his new palace at Yuste, where he kept even his own family at bay (not even his daughter Juana received permission to visit) and utterly refused to discuss public affairs. But much though the emperor may have wanted to ignore the world, the world refused to ignore him. In July 1556 Paul IV excommunicated both Charles and his son, placing their lands under interdict.

Given his role in bringing England back into obedience to Rome, Philip complained bitterly that the pope’s actions

lacked justification, reason and cause, as all the world has seen, because I have not only given him no cause for this, but rather His Holiness owes me favour and honour because of the way I have served and revered him and the Holy See, both in bringing England back to the Faith and in everything else I could do.28

Philip did not merely complain: he also ordered Juana to convene a special committee of Spanish theologians and lawyers to advise him on how best to respond to the pope’s declaration of war. They proposed a radical solution, suggesting that a ‘National Council should be held in Spain to reform ecclesiastical affairs’. Indeed, the committee suggested, ‘it should be held for all Your Majesty’s dominions, and those of your allies’ – in other words, for half the Catholic world.29

The burden posed by simultaneously fighting the pope, France, the Turks and some Italian states seems to have shaken the king’s confidence, and he sent Ruy Gómez to persuade Charles to leave Yuste and take charge of Spain once more.

Begging Your Majesty with all humility and insistence to agree to act, helping and assisting me in this crisis not only with your advice and council, which is the greatest asset I could have, but with your own presence and authority, leaving your monastery and going to whatever place would be best for your health and for dealing with public affairs.

In addition, he instructed Ruy Gómez to ‘ask His Majesty to send me his opinion concerning the war, and about where and how I can best undertake and participate in this campaign in order to achieve the greatest results’.30

The warrior king

While he impatiently awaited answers, Philip tried to obtain a declaration of war by England against France. The marriage treaty with Mary expressly prohibited the king from involving his new subjects in the war then raging between Charles and France, but Philip argued that the conflict unleashed by Paul IV was a new conflict and, to sell this argument to his subjects, in March 1557 he returned to England, where he spent the next three months. He then returned to Brussels to take charge of the war.

Despite his dexterity in tournaments and jousts on foot and horseback, Philip had never been exposed to mortal combat and he hoped that the 1557 campaign would change this. From the outset, he kept a tight control over strategy, military operations and logistics, and at the end of July (still in Brussels) he notified Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy, who commanded his field army, that ‘We have decided that you should set forth on Thursday and lay siege to St Quentin’, adding ‘I will travel straight to Cambrai, where I hope to be on Saturday. I will be in Cambrai on Saturday without fail’ (a strange repetition, perhaps a sign of uncertainty). From there, he concluded, ‘I expect to join you on Tuesday,’ 3 August.31

Such micromanagement revealed Philip’s lack of military experience. While Emmanuel Philibert’s troops dug trenches around St Quentin the king and the siege train remained marooned at Cambrai, twenty-five miles to the north, unable to move until the 7,000 English troops sent by his wife arrived to escort them. ‘I greatly regret that I cannot leave today, as I planned,’ he wrote to Savoy on 6 August. In a holograph letter the following day he again lamented ‘I am very angry that I have not been able to leave, nor can I leave soon, because the English tell me that they will not arrive here until Tuesday [10 August], although I have told them to hurry up.’ When the English had still not arrived on 9 August, Philip became frantic with worry that a battle would take place without him, urging Emmanuel Philibert somewhat incoherently:

If you cannot avoid fighting before I can be there, which will be without fail when I have said, I cannot emphasize too much – since you can see that nothing could be more important to me than that this matter turns out as I want – that you should send me news of it by sending three or four messengers here, flying at top speed, so that there will be time and opportunity for me to get there in time. I know that you would not want me to be absent in such a situation, and you know how important it is to me, so I do not want to stress it any more, although I would like to tell you about it at length.32

It was not to be. The next day, 10 August, St Lawrence’s Day, the French tried to relieve St Quentin, and Emmanuel Philibert gave battle. Perhaps 5,000 French troops perished in combat and thousands more fell prisoner, including numerous nobles. Carranza, now in Brussels, marvelled that ‘we are distributing French dukes and counts among the local castles’; adding, ‘the day before yesterday three hundred French soldiers passed through, and cartloads of prisoners constantly arrive’. Fourteen years later, one of Philip’s councillors still remembered with satisfaction the day when ‘we knocked the French for six’.33

The stunning victory of his forces at St Quentin led the absent king to commission two memorials. First, he commissioned a magnificent stained-glass window in the church of St John of Gouda, as did several of those who had commanded troops in the battle (see plate 17). Second, he founded a monastery and mausoleum at the village of El Escorial north-west of Madrid, dedicated to St Lawrence, because ‘he realized that such an illustrious commencement of his reign came through the Saint’s favour and intercession in heaven’.34 But that lay in the future. A few days after the battle, he entered the trenches around St Quentin at the head of his English troops, including several exiles and former rebels anxious to win the king’s trust (Lord Robert Dudley, later Queen Elizabeth’s Favourite, among them) and took personal charge of operations. ‘His Majesty was on horseback, holding his commander’s baton in his hand,’ wrote an eyewitness, and that is how he appears in a famous portrait by Antonis Mor (see plate 9). Two weeks later, after battering the walls of the town ‘with great fury, His Majesty was at the head of his troops’, ready to lead an assault, but he resolved ‘to wait, to see if the French inside the town, seeing their predicament, would surrender’. They did not, and so after another artillery bombardment the next day, according to Philip’s own account: ‘We entered St Quentin on all sides, killing all those whom we could find during the fury of the first assault.’ ‘Our Lord in His goodness has desired to grant me these victories within a few days of the beginning of my reign,’ he crowed to his sister Juana, ‘with all the honour and prestige [reputación] that follow from them.’35

The king also tried to micromanage the duke of Alba’s campaign in Italy. Having forced the French army to retreat from Naples, on 28 August 1557, the same day that Philip’s forces sacked St Quentin, Alba’s artillery began to fire on the walls of Rome and his troops looked forward to ‘a little plunder’. But the duke restrained them ‘because the king had forbidden him to enter’ the city, ‘ordering him to cause only fear, not damage’.36 This strategy worked: two weeks later, Pope Paul IV solemnly swore that he would never again make war on Philip or assist others who did, and that he would never rebuild the razed walls of the captured towns returned by the duke. The pope’s ignominious surrender delivered control of all Italy to Spain, and Paul’s reckless Italian allies hastened to make peace with Philip on the best terms they could.

These great victories came at a high cost, however. In May 1557 Philip had issued a decree forcibly converting the capital and interest of all outstanding short-term loans assigned for payment from his Castilian revenues into bonds bearing fixed interest of 7.14 per cent: the first default on sovereign debt in Spanish history. For a time Philip managed to raise more money from a few firms, exempting them from the terms of the decree provided they made new loans. He also exploited his father’s sense of pride in the victory of St Quentin to plead once more with him ‘as emphatically as I can, to take a hand in raising money for me’; and this time, after almost a year as a recluse, Charles dictated and signed a stream of forceful letters to his former ministers urging them to help his son immediately.37 These funds allowed Philip and his troops to capture and sack several more French towns, and in October 1557 he returned to Brussels to plead with the States-General for more money, but they refused. As Philip explained to Emmanuel Philibert, ‘we will have to demobilize the army at the end of this month, because that is when the money runs out. The army has grown in size, and it costs more than we expected. I can see no way to support it.’38 Meanwhile Henry II recalled his troops from the Italian peninsula.

Far away in Yuste, the dangers inherent in these two developments caught the emperor’s experienced eye. ‘If the enemy finds that you have demobilized,’ he warned his son in November, ‘he may decide to concentrate his forces and make an attempt this winter to recapture some of the places he has lost – or to gain some new ones.’ He therefore advised Philip to maintain a large force in the vicinity of Metz, so that ‘with those troops you can with greater assurance challenge the enemy to prevent him from achieving any of his goals’. This, the emperor concluded, would not only strengthen Philip’s own forces but also enable him ‘to assist your allies’ – a veiled reference to the need to protect Calais. But Philip never saw the letter! He had decided some time before that he did not have time to deal with his father’s numerous, verbose and often self-centred missives: instead he read the summaries prepared by his secretary, Francisco de Eraso. This time, Eraso totally omitted Charles’s strategic insight from ‘The points and items that the emperor raises with Your Majesty’ and endorsed the letter itself: ‘Nothing to respond to here’.39

Events soon revealed the wisdom of the emperor’s warning. On 31 December 1557, some 30,000 French troops invaded the English enclave around Calais and captured one outpost after another. In Brussels, Philip recognized the danger and invited the English commandant to let him know ‘if you need anything from us to improve your security and defence, because we would be happy to oblige’.40 The French captured the entire Pale within three weeks, transforming the strategic situation. For Spain, ‘it has created great confusion in our affairs, because just as we thought that the wars were over, it seems that they are starting again’. The ‘confusion’ for England was even greater, and Mary was devastated: according to a popular story, she claimed that when she died the word ‘Calais’ would be found ‘engraved on her heart’.41 Her only consolation at this time was a new pregnancy.

Cardinal Pole informed Philip of the pregnancy in January 1558, and the king responded that he had experienced ‘more delight and pleasure than he could express on paper, because there is nothing on this earth that he had wanted more, and because it is so important for the well-being of the faith and of our realm’. So sure was Mary of her condition that on 30 March, ‘foreseeing the great danger which by Godd’s ordynance remaine to all whomen in ther travel [travail] of children’, she made a new testament that named Philip as regent ‘during the minoryte of my said heyre and issewe’. She also kept the Royal Navy on standby at Dover and ‘smartened up all lodgings between here and the coast’ lest her ‘gentle prince of Spain’ should ‘come again’. The count of Feria, Philip’s personal representative to the queen, advised his master that ‘all she can think of is that Your Majesty should come’.42

Philip agreed: the key to the future lay in whether Mary, now aged 42, was pregnant or not – and as early as February 1558 he lamented that ‘the queen writes nothing to me about the pregnancy, which I take as a bad sign’. A month later he repeated that ‘in the matter of the queen giving birth, it would be best to believe someone who actually saw it, and until then not to get our hopes up’; and in April, nine months after he left England, ‘News that the queen has given birth is now long overdue, and so it seems we may have been mistaken’. The thought so depressed him that ‘I have now become the enemy of speaking and writing to anyone, and so I don’t want to say any more.’43

Whether or not she was pregnant, Mary’s expectation that her husband would visit her again was entirely realistic – couriers regularly travelled between Brussels and London in four days, and Philip himself had once crossed the Channel in two and a half hours – but it never happened. First, the king fell ill. In February 1558 he was laid low by a fever ‘which has left me very weak and weary’ and ‘right now I cannot eat anything’; worse, ‘everything has gone to my chest and so I can’t sleep at night’. Feria must tell the queen all this to explain why he could not visit her. The next week brought new complaints. ‘My chest still troubles me, and I’m in such a state that until now I have not dared’ to leave the palace. And then, when ‘I went riding for a while’ on horseback ‘I had to rest two or three times on the way out and the same on the way back’.44

In a letter dated 1 May 1558, Feria advised his master that even Mary had now accepted that she was no longer pregnant, and that ‘she sleeps very badly, and is weak from melancholy and illnesses’. This made it imperative for Philip to ‘speak and write’ to his wife about recognizing her half-sister Elizabeth as her heir. Philip complied. ‘I am writing to the queen,’ he assured Feria, ‘praising the way Elizabeth is behaving’, adding that the queen ‘must realize that if she should die, she will leave behind a kingdom that is hostile to me’.45 To avoid this, he decided to pay a flying visit to see both his wife and his sister-in-law – but at the last minute he had to abandon his plan because French forces launched a surprise attack. Philip had just forfeited his last chance not only to see his wife but also to place her successor in his debt: persuading Mary to recognize Elizabeth’s rights would have greatly increased his influence in England.

Instead, Philip concentrated on organizing opposition to the French troops who invaded Flanders and captured several ports until, on 13 July 1558, Egmont transformed the situation by ambushing the invaders outside Gravelines, killing or capturing most of them. Two weeks later, Philip (‘who seemed very happy’) visited his army, congratulated Egmont, and accompanied his troops over the next two months as they invaded France again. Although he himself did not participate in any more military operations, a task he left to the duke of Savoy, he did hold regular meetings to decide strategy. Sometimes Philip summoned Emmanuel Philibert to report in person ‘because it is easier to understand these matters in a conversation than in a letter’; at other times he went to the duke’s headquarters and listened as his generals and civilian advisers debated the options. In September 1558, as the campaign season drew to a close, at a special meeting of his principal ministers – Dutch, Italian and Spanish – a consensus emerged in favour of Granvelle’s proposal that Philip should conclude a ceasefire that left his troops in control of much of northern France and use that advantage to negotiate a lasting settlement.46

At first this goal seemed unattainable because the French wanted Naples and Milan; the English insisted on the return of Calais; the duke of Savoy expected all his lands back; and Philip demanded Burgundy and Picardy. The French argued that the most effective way to settle all their disputes with Philip was for his son, Don Carlos, to marry Henry II’s eldest daughter Isabel, but they insisted on settling outstanding issues with England first. Philip shrewdly warned the English negotiators that ‘The nature and custom of the French (as you doubtless know) is to be harsher and less tractable at the beginning, but the passage of time renders them more pliant and tractable’, and he generously proposed that they ‘asked for Calais as the dowry’ for his French bride, which he promised to give back to England; but the English angrily (and, it soon emerged, foolishly) rejected this because it called into question their sovereignty over the area. The impasse only ended when news arrived of Mary Tudor’s death on 17 November 1558.47

Ex-king of England

Rumours concerning the queen’s ill health had circulated for some time, leading Philip to discuss with his advisers the best way to keep England Catholic should Mary die. In October 1558, on learning that the queen’s ‘life was at risk’, he ordered Feria ‘to go and see the Lady Elizabeth, and treat her as [my] sister and ensure that she accedes to the crown without disturbance’. It was too late: Mary’s councillors had already persuaded her to recognize Elizabeth as her successor. Mary died a week later, and her husband’s title ‘king of England, Ireland and France’ died with her.48

Philip had achieved much in England, especially in the matter of religion. In October 1554, three months after Philip married Mary, a Spanish visitor lamented that ‘The friars who have come here [from Spain] are always confined to their convents and only go to say Mass. They do not dare to go into the streets, unless accompanied by many Spaniards, because they would be stoned.’ What a contrast with the situation five years later, when even Protestants expressed grudging amazement at the success of Philip’s efforts:

Our universities are so depressed and ruined, that at Oxford there are scarcely two individuals who think with us, and even they are so dejected and broken in spirit, that they can do nothing. [Some] despicable friar[s] … have reduced the vineyard of the Lord into a wilderness. You would scarcely believe that so much desolation could have been effected in so short a time.49

Soon after her accession, Elizabeth had to replace the heads of almost every Oxford college, almost all the bishops and two-thirds of the deans and officials who had served her sister because they all remained loyal to the pope. As Eamon Duffy correctly observed, ‘It was the death of the queen, not any sense of failure, loss of direction or waning of determination’, that ended the Catholic England recreated by Philip and Mary. Even without ‘issewe’ from his marriage to Mary Tudor, a durable Catholic establishment would probably have emerged in England had the queen lived to be 56, like her father, Henry VIII – let alone 70, like her similarly childless sister Elizabeth. Instead Mary died at age 42.

Mary Tudor was not the only relative whom Philip mourned. On 1 November 1558 he received word of his father’s death at Yuste six weeks earlier. The news left him distraught and he at once retired to the monastery of Groenendaal near Brussels. When Emmanuel Philibert visited him there to transact some pressing business twelve days later, ‘I found him very sad’; and when he learned that Mary of Hungary had also died, Philip lamented to his sister Juana:

It seems that everything is failing me at the same time. Let us bless God for what He does, because there is nothing I can say, except to accept His will and beg that He will be satisfied with what has happened so far … These deaths cannot but create problems for me, and give me a lot to think about in how to govern these provinces, and how best to deal with England, depending on whether the queen should live or die.

He concluded on a note of self-pity: ‘I don’t even want to mention how I myself feel, because that is what matters least.’50

His worst fears were realized on 7 December, when he heard that not only Mary Tudor but also Cardinal Pole had died. Four days later, according to his confessor, ‘His Majesty is so depressed by the death of his father and the others, which so afflict him that he does not want to see anyone for a while.’ Three weeks later, still in solitude at Groenendaal, Philip painted a sombre picture of his situation.

I have no money to pay for any of the many things that must be done, so that I cannot maintain myself any more with the resources of the Netherlands. Nor can I go to Spain without making peace first, because it would not look good and would dishearten these provinces – although my presence here does nothing to win them over, but rather alienates them.

Indeed, he mused disconsolately, ‘I think they would be happy with any sovereign except me.’51

Ever since he started to govern, fifteen years before, Philip had craved independence and respect – and resented the fact that he did not seem to get them. As he scribbled angrily on the dorse of one of Mary of Hungary’s hectoring letters to ‘Your Highness’ in spring 1558:

You will see from this letter that the queen certainly knows how to make her case, and that she must have advisers who tell her what would be best for her, without showing me the respect that they should have for me, because they do not want to recognize my status. I want no one to rank above me in these realms of mine, except for His Majesty [Charles V].52

Now that both Mary and ‘His Majesty’ were dead, Philip’s wish had come true. As he entered his fourth decade, after the long apprenticeship, he could now issue orders ‘by virtue of our own will, certain knowledge, and absolute royal authority, which in this matter we wish to use and do use as king and sovereign lord, not recognizing any temporal superior on this earth’.53 Besides respect and authority, he also possessed absolute freedom in his personal life: he could get up and go to bed whenever he wanted, take as long as he liked to shave and get dressed, come and go as he pleased, speak or be silent whenever and wherever he chose, and surround himself with Fools and jesters as much as he desired. How would he make use of all these new freedoms?