Years of adversity, 1573–1576

‘The greatest and most important matter that I face, or could ever face’

BY January 1573, Philip had lost confidence in the ability of the duke of Alba to suppress the Dutch Revolt and decided that finding an immediate and permanent solution to the Netherlands problem had become ‘the greatest and most important matter that I face, or could ever face’. He therefore ordered Don Luis de Requesens, governor of Lombardy (and formerly his chief page), to leave immediately for the Netherlands to replace Alba and end the war ‘through moderation and clemency’.1 Almost immediately the Venetian Republic made a separate peace with the sultan, leaving Philip to withstand the Ottoman incursions in the Mediterranean virtually alone, and since Requesens demanded various favours before he would accept his new post, the king instructed Alba to make peace as soon as possible and at almost any price:

It is essential that we bring affairs to a conclusion, as much to avoid the loss and destruction of those provinces as because of the impossible financial situation that we face. So I request and require you most earnestly to arrange things so that we may gain days, hours and even minutes in what must be done to secure a peace.2

As usual, the king’s insistence on a radical change of policy 700 miles away proved totally unrealistic. The courier carrying this crucial dispatch only arrived in the Netherlands six weeks later – long after the fall of Haarlem, which would have afforded an admirable opportunity for clemency – and by then the Spanish army had begun to besiege Alkmaar, a town in North Holland recently fortified in the Italian style. ‘I do not see this as a difficult enterprise,’ Alba boasted, and indeed many of the town’s inhabitants favoured surrender; but the duke once again insisted on unconditional surrender – and when his artillery failed to open a breach in the town’s powerful defences and his troops refused to launch an assault, he had to withdraw. For the first time, a Dutch town had successfully defied Philip.3

The king did not know what to do. In one of the tortuous holograph letters in which he pleaded with Requesens to go immediately to the Netherlands, he summarized the contradictory advice that he had received on the subject. Alba and his supporters, he wrote, saw the revolt as primarily religious and therefore impossible to end by compromise, whereas most Netherlanders ‘take the opposite position and say that very few rebels acted for reasons of religion, but rather through the ill treatment they have received in everything, especially through the troops and most of all through the Tenth Penny’. They therefore contended ‘that the solution to everything lies in mildness and good government’. The king confessed:

With so many different opinions I have found myself in a quandary, and since I do not know the truth of what is happening there I do not know which remedy is appropriate or whom to believe; so it seems to me safest to believe neither the one group nor the other, because I think they have [both] gone to extremes. I believe it would be best to take the middle ground, although with complete dissimulation.4

Philip therefore prepared two contradictory Instructions for Requesens. ‘You will see that those written in Spanish lean somewhat in one direction,’ he explained, ‘while those written in French very clearly go in the other.’ The king apologized for the difficulties this contradiction might cause, but concluded feebly: ‘I did not want to burst my brains emending them except for small things, because your real instructions will be what you see and learn when you get there.’5

Once Requesens arrived in Brussels in November 1573 and began to ‘see and learn’, he informed his master:

There is no doubt that if we could pacify these lands just with force and troops, it would be best for the service of God and Your Majesty, and it would preserve your reputation better because you could do what you liked with them, so that using clemency at that time would be more admired.

Unfortunately, he continued, ‘I find this rebellion in the worst state it has ever been’, with a military stalemate, huge debts to the troops, an unsustainable operating budget, the risk of more mutinies and an army so widely scattered that it was out of control. Spain could not continue to tackle the rebellion in this way. Requesens went on to make a telling comparison. Three years before, Philip had begun talks ‘with the Moriscos of Granada, at a time when your position was more favourable than it is now here’, and this had opened the way to peace. Requesens recommended doing the same now, because the king’s opponents did not all share the same motivation. ‘For the prince of Orange and many of those who follow him, religion was (and still is) the major issue,’ Requesens argued, ‘but I do not believe this is true for most people here. Rather, they [rebelled] because of the taxes imposed on them and the outrages they have suffered at the hands of your troops.’ Requesens therefore recommended issuing a General Pardon to all those willing to live as Catholics under Philip’s rule.6

Philip now tasked his council of State with discussing ‘if this is the right time to issue a General Pardon, and if so what form it should take’, as well as whether to open direct negotiations with Orange. One councillor reminded his colleagues that ‘if we try to proceed with harsh measures, the war will last longer than we think’ – a telling criticism of Alba’s claims that total victory lay just around the corner. Everyone agreed ‘that we must issue a General Pardon’; they also agreed that ‘Your Majesty should revoke the Tenth Penny and abolish the council of Troubles, which everyone in the Netherlands hates so much’. Like Requesens, the councillors drew some telling parallels, including the measures taken by Charles V half a century before, suggesting that the king should announce all his concessions at the same time, ‘as was done in Valladolid during the Comunero revolt’. Finally, the council recommended granting Requesens discretion ‘because he is the man on the spot, and knows what is happening from hour to hour; so he can see better than anyone what is best for the service and authority of Your Majesty.’7

After much heart-searching, in May 1574 Philip accepted this advice. He authorized Requesens to abolish both the new taxes and the council of Troubles, and sent him four different versions of a General Pardon, with full discretion to promulgate the text he judged most appropriate. Requesens chose (as Philip duly noted) ‘the version modelled on the one for Comuneros of Castile’. It excluded only 144 rebels.8

War on two fronts

Why, then, did these concessions not end the Dutch Revolt whereas similar ones had ended the Comunero uprising fifty years before? From Italy, Cardinal Granvelle put his finger on the central problem: suspicion. ‘I know the nature of those people,’ he warned. ‘Many Netherlanders have sinned through weakness, others through fear, and others still because they were pressured to do so’: it would be difficult ‘to remove their fear and suspicion that at some future date they will be put on trial and punished’. Indeed, the cardinal quipped, ‘even if Christ himself arrived to govern them, they would still complain and make demands’. In Madrid, another minister pointed out to Philip an essential corollary to issuing the General Pardon: ‘It is essential to send funds together with these concessions, because if we show military weakness, the Dutch will believe that you gave way because you had no choice.’ Requesens commanded 60,000 men, which ‘is more than enough to conquer many kingdoms – but not to crush all the heresy and wickedness that exist in the rebellious towns’. Moreover, those 60,000 men all had to be paid, on top of the money required to fund the Mediterranean war and all the other needs of the Monarchy.9

Some ministers advocated solving this financial dilemma by scaling back the war in the Mediterranean so that Philip could concentrate his resources on recovering the Low Countries, but the king disagreed: ‘The sultan has mobilized more forces and is so angry with me’ that rather than waiting for the inevitable Ottoman attack, and then trying to respond, it would be more effective and also cheaper ‘to proceed with the campaign we have planned, which will maintain our reputation and also restrain the Turks, France, and the independent states of Italy, which might dare to do something if they detect any weakness in me’. In addition, abandoning the campaign would mean ‘forfeiting the 800,000 ducats, more or less, that have already been spent’. By contrast, the king predicted optimistically, for just a few ducats more Don John of Austria and his fleet might score another victory.10

Philip changed his mind when news arrived that Venice had concluded a separate peace with the sultan, and hastily sent agents to Constantinople with powers to conclude a truce; but he still allowed the campaign to go forward. In October 1573 Don John launched a surprise attack that captured Tunis and neighbouring Bizerta. The arrival of this news in Constantinople naturally brought all talk of a truce to an abrupt end, which placed Philip in an extremely serious situation. When in April 1574 Don John sought permission to ‘set forth with the fleet to prevent the enemy from achieving anything’, his brother refused and instead ordered him ‘to go to Milan until further orders, there to monitor developments in all areas and to respond accordingly’.11

The first development occurred in the Netherlands, where Louis of Nassau invaded again at the head of an army raised in Germany. Initially fate smiled on Philip: the Spanish veterans sent by Requesens to intercept the invaders routed them at the battle of Mook, but the victors promptly mutinied for their wage arrears and occupied Antwerp, which they held to ransom for six weeks until they received satisfaction – at a cost to the king of some 500,000 ducats. Requesens immediately grasped the deleterious consequences of these prolonged disorders, complaining to a colleague that ‘it was not the prince of Orange who had lost the Low Countries, but the soldiers born in Valladolid and Toledo who had driven money out of Antwerp and destroyed all credit and reputation’. Requesens claimed that ‘within eight days His Majesty would not have anything left here’, and he told Philip that even if ‘it was not the Original Sin of this country to hate [all Spaniards], these mutinies by our own troops, and the damage they cause, would suffice to make us loathed here’. Granvelle, for his part, predicted pessimistically (but accurately) that ‘if we fail to gain the goodwill of those provinces, they will eventually ruin both Spain and the reputation of His Majesty’.12

Once ‘the soldiers born in Valladolid and Toledo’ had returned to obedience, Requesens launched them against the city of Leiden, judging that its capture might fatally weaken the rebels because it would separate North Holland from Zeeland. Leiden did not boast state-of-the-art defences like Alkmaar, and the Spaniards managed to seal it off from the outside world with a chain of blockhouses. Then, in late September, as the starving city prepared to surrender, Orange gave the order to open the sluices and dikes to allow a fleet of shallow barges to bring relief. Although this stratagem failed, as the waters rose ‘a great and sudden fear possessed the Spanish infantry’, who unexpectedly abandoned their posts and fled. For the second time, a Dutch town had successfully defied Philip.13

Alternative strategies: fire, flood and a fleet

Requesens and his senior commanders now suggested to the king that ’since the defiance and rebellion of the people of Holland persist, we must burn and destroy all the villages and fields’ on whose crops the towns depended, and also consider the possibility of ‘flooding this country, since it is in our power’, given that many areas in revolt lay below sea level.14 Philip gave careful consideration to both of these indirect strategies. ‘It is very clear,’ he informed Requesens, ‘that the severity, wickedness and obstinacy of the rebels have reached the level where no one can doubt that they are worthy of a harsh and exemplary punishment.’ He recalled that the duke of Alba had suggested ‘burning them out’ (standard military practice in enemy territory) and ‘if it had been the land of another prince, the duke would have done it without consulting me and he would have done well; but he held back, because it was mine, and likewise I refrained from giving the order’. But now, seeing that the rebellion continued,

it seems appropriate to use the ultimate, rigorous punishment. We suppose that this could be done in one of two ways: either flooding the said villages and countryside, or by burning them, although we would gladly avoid both. However the wound is already so cancerous that it is necessary to apply strong medicine, and to apply very strong pressure, because it is clear that by letting the rebels enjoy the produce of the earth … [they can] sustain the war as long as they want.

Concerning which of the two strategies to implement, the king admitted:

Flooding Holland could be achieved easily, by breaking the dikes; but this method brings with it a big disadvantage: that once broken it would result in their loss and destruction for ever, to the evident detriment of the neighbouring provinces … In effect, this method cannot be used, nor should we use it, because (in addition to the disadvantages mentioned, which are great and manifest) it would bring with it a certain reputation for cruelty that should be avoided, especially among vassals, even though their guilt is notorious and the punishment justified.

Instead, Philip continued, ‘burning is better, because (in addition to its use being appropriate in warfare) it can be stopped’ as soon as the rebels ‘beg for the mercy that I would wish to grant them. And in this way, we would swiftly achieve the end that is desired.’15

Although the strategic use of terror might have succeeded, as with the king’s ‘clemency initiative’ the previous year his change of plan came too late to be effective. Anticipating a favourable decision, Requesens had already sent Spanish units into the rebel heartland to break a few dikes and torch some farms; but after a few days, the veterans threatened that unless they received their wage arrears at once they would abandon their posts. Since Requesens could find neither the money nor replacement troops in time, in December 1574 the Spanish garrisons left North Holland, never to return.

The king showed admirable analytical rigour in evaluating these two ‘indirect strategies’ – burning or flooding – but he failed to do the same with a third initiative designed to defeat the Dutch rebels: creating an Atlantic fleet. ‘Since the day I assumed responsibility for this war’, Requesens claimed, he had ‘often written’ to his master that ‘it is impossible to end this war without warships sent from Spain’. Philip acted on this suggestion in 1574. He had over 200 ships seized in the ports of Cantabria and instructed Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, who had successfully expelled the French from Florida, to equip the best of them with ordnance and munitions ready ‘both to clear the Channel of pirates and to regain some of the Dutch ports occupied by the rebels’. The king also raised 11,000 soldiers to serve on the new fleet.16

These orders reveal Philip’s lack of strategic and operational experience. First, it took months to locate and load the artillery and other equipment required to turn any embargoed merchantman into a fighting ship so that, as Menéndez crudely stated, creating a suitable fleet ‘could take several years’. Moreover, once in northern waters, a large fleet from Spain would need a suitable harbour in which to shelter in case of need, and Philip no longer controlled one. Finally, when news reached him that a large Turkish fleet had left Constantinople for the west, the king ordered Menéndez to keep close to Spain, so that his fleet could ‘assist where it was most needed’ – in the Atlantic or the Mediterranean, depending on the circumstances.17 In the end it made no difference: in September 1574 an epidemic decimated a large part of the expeditionary force, killing Menéndez, and Philip cancelled the entire expedition. He had squandered over 500,000 ducats on it – all for nothing.

Between a rock and a hard place

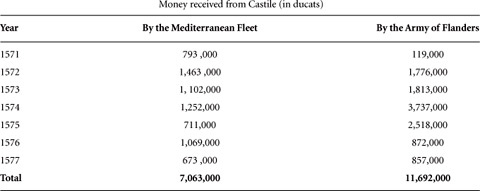

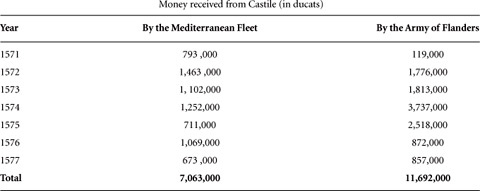

Although his other realms made substantial contributions, Castile provided the lion’s share of the budget for both of Philip’s wars, and although the totals in Figure 13 are massive, they record only the money received by Philip’s armed forces abroad from Castile, not the money that the kingdom actually provided: his treasury also had to pay transport charges and interest. In February 1574, officials calculated that Castile had spent 22 million ducats on the Netherlands since the duke of Alba left the court seven years before; and now defending the Mediterranean cost almost as much as fighting the Dutch.

13. The cost of war on two fronts, 1571–7. The cost to Spain of defeating the Turks at Lepanto in 1571 remained relatively low, thanks to contributions from Philip’s Italian dominions as well as from his allies, but the campaign of the following year, although it achieved nothing, cost twice as much. After Venice made a separate peace with the Turks in 1573, Philip’s subjects had to shoulder almost the entire burden of Mediterranean defence. At the same time, the cost of suppressing the Dutch Revolt soared. Since the total revenues of the crown of Castile barely exceeded six million ducats, of which half went on servicing previous loans, the treasury quickly ran up huge debts. In September 1575 Philip issued a ‘Default Decree’ suspending all payments.

The haemorrhage of funds on this scale could not continue, and Philip authorized two remedial measures: he summoned the Cortes of Castile and asked them to vote new taxes, and he set up a secret committee (later known as the Junta of Presidents because it included the presidents of several councils) ‘to discuss all major fiscal matters’. Initially the king considered chairing the junta himself, but ‘my normal duties do not allow me to do this’; instead, he entrusted the task to Diego de Covarrubias, who had succeeded Espinosa as president of the council of Castile, and therefore as royal spokesman in the Cortes. Philip warned Covarrubias that solving the financial crisis was ‘the most important item of business that there could be, because I believe the conservation of religion and of Christendom largely depend on it – and this worries me far more than if it affected just me’. The king lamented that ‘everything is in such a state that, unless we find and provide a remedy, I cannot but fear that [my entire Monarchy] will collapse very soon’; and he believed that enabling ‘my treasury to fund all ordinary and extraordinary expenditures’ required three things:

First, finding new revenues, since there is now so little – or, more accurately, nothing – to fund what is necessary. Second, dealing with the bankers who are charging interest, to ensure that they cease and do not consume all our resources, as they are doing now. Third, rescheduling my debts.18

After reviewing a mountain of papers, the Junta of Presidents estimated that the king owed at least 35 million ducats on loans that needed to be re-scheduled, and it proposed that the Cortes increase the sales tax (alcabala) levied on certain goods, but at the same time devolve collection to the principal cities of Castile in return for an annual lump sum paid in advance. Although the Cortes did not rule out this proposal, it demanded numerous other concessions: the suppression of all taxes imposed by the crown without the consent of the Cortes; restrictions on the export of bullion from the kingdom; and a promise that the king would not alienate to bankers the revenues freed up by rescheduling his debts in return for new loans. When Philip refused to make all of these concessions, the deputies declared that they needed new instructions from the towns they represented, forcing the king to suspend the session.

The intransigence of the Cortes of Castile, combined with the death of several trusted advisers (Feria in 1571, Espinosa in 1572, Ruy Gómez in 1573), seems to have convinced Philip that since he could not understand his financial situation himself he needed to find someone who could. ‘I see no alternative to granting someone oversight in all treasury matters,’ he wrote early in 1574, and he turned to Juan de Ovando, priest, inquisitor and a disciple of Espinosa, who as president of the council of the Indies had rationalized the crown’s efforts to govern America.19

Ovando soon submitted to Philip a series of documents that analysed Castile’s underlying financial problems. First, he proposed that, as an emergency measure, all the crown’s fiscal officers should report to him while he alone would report directly to the king, streamlining both the formation and implementation of policy. Ovando next explained the current fiscal problems in a form that even Philip could understand, written in unusually large script and using only simple terms, as if for a child (see plate 36). It began: ‘In order to understand and make use of the Royal Treasury, we need to consider four basic things’:

1.‘What do we have?’ Ovando estimated that the annual revenues of the crown of Castile amounted to less than six million ducats.

2.‘What do we owe?’ The total came to over 73 million ducats.

3.‘What do we have and what do we lack and need?’

Ovando hardly needed to state the obvious, but he did so anyway: ‘We can see that we owe far more than our income, and we lack everything that we need.’ Specifically, the royal household and local defence absorbed almost 100,000 ducats a month; interest on government bonds required a further 250,000 ducats; while maintaining ‘armies and navies strong enough to oppose and defeat our Ottoman and Protestant enemies’ required over a million ducats a month. Ovando estimated the treasury’s commitments for the year 1574 at almost 50 million ducats whereas its income, he reminded his master, was less than six million.

4.‘How and where can we fill the gap?’ Surprisingly, Ovando did not suggest reducing expenditure ‘to oppose and defeat our Ottoman and Protestant enemies, because unless we defeat them, they will surely defeat us’. Instead, he proposed two ways to fund the king’s existing policies: raising income and reducing debt payments. For the former, he favoured further increases in the alcabala as well as seizing all silver and gold aboard the next fleets to arrive from America. To reduce debt payments, he recommended not only unilaterally lowering the interest rate on all government bonds but also issuing a Default Decree (Decreto de Suspensión) that would freeze both the capital and accrued interest on all loans signed with bankers since 1560, forcing lenders to accept low-interest bonds as repayment. Ovando insisted that all these measures must take effect simultaneously: the Cortes should increase the sales tax at the same moment as the king issued the Default Decree and his officials in Seville confiscated the treasure.20

While he pondered Ovando’s solutions, Philip strove to secure divine favour. When news arrived that Louis of Nassau was about to invade the Netherlands while a Turkish fleet seemed poised to avenge the loss of Tunis and Bizerta, the king urged the clerics of Castile to pray for a miracle, since one was ‘so necessary, as you must know. I hope this will lead Him to pity us, since the cause is His.’ He also prepared to revise his testament, because although ‘I hope that God will give me life and health, which He can use for His service, it is good to be prepared, and if things go as badly in the future as they are going now …’ – the king scratched out the rest of his sentence (a very rare event in his correspondence).21

In mid-May 1574, news that mutinous Spanish troops had entered Antwerp, and were holding it to ransom, deepened the king’s despair. ‘Unless God performs a miracle, which our sins do not merit, it is no longer possible to maintain ourselves for [a few] months, let alone years; nor can life and health withstand the anxiety caused by this, and by thinking of what may happen – and in my lifetime.’ Two days later he wailed: ‘These are things that cannot fail to worry me and make me anxious’; and two weeks later, he again concluded that only divine intervention could save Spain: ‘I believe the moment that I have always feared has arrived, through lack of money. I fear that we cannot find a remedy in time unless it comes from God, who can do everything, and that is what I hope for and what sustains me – although I do not think we deserve it.’ By the end of May, even those faint hopes had dissipated:

I fear that our lack of money means that the rebels will not want to negotiate or anything, and I am as sure as is possible in these circumstances that the Netherlands – and even the rest of the Monarchy – will be lost, although I hope that God will not permit or wish it because of the harm it will do to His service … It is a terrible situation and it is getting worse every day.22

When yet more bad news arrived in June 1574, Philip lamented anew that ‘I am thinking that everything is a waste of time, judging by what is happening in the Netherlands, and if they are lost the rest [of the Monarchy] will not last long, even if we have money’. The following month, he repeated the same refrain:

The Netherlands are very much at risk, with so many troops and no money to pay them, and so we must send financial help without delay. Our affairs there cannot be improved without money unless God performs a miracle … Once we lose the Netherlands, however many millions we might have here will not suffice to prevent the loss of all the rest [of my dominions].

When neither miracle nor money materialized, the king sighed: ‘We are running out of everything so fast that words fail me.’23

At least Philip scored one partial success. In August 1574, he made a peace that restored diplomatic and commercial relations with Elizabeth Tudor and obliged both parties to desist from assisting rebels against the other – but almost immediately he allowed Inquisitor-General Don Gaspar de Quiroga to nullify one of its advantages. At a meeting of the council of State Quiroga argued that in order to avoid the ‘contagion’ of heresy, no Protestant should be allowed to set foot in Spain. Philip referred the matter to the Suprema, which opined that all future English ambassadors must be Catholics (or else the ambassador must allow his baggage and that of his entourage to be searched for prohibited books); and that they must revere the Holy Sacrament at all times, say or write nothing against the Roman Church and refrain from discussing Catholic doctrine. Any deviation would incur the normal penalties imposed by the Inquisition. The king supported this tough line, which perhaps encouraged Quiroga to harden his position: ‘I say that the queen must not succeed in placing an ambassador here with the freedom to practise his creed in private’. Indeed, ‘since the queen is who she is, we should not accept even a Catholic ambassador [from her]’. Once again, Philip sided with the Inquisition: there would be no more Tudor ambassadors in Spain, even though the lack of diplomatic representation increased the likelihood of another inadvertent lurch into war, as it had done in 1569 (chapter 11).24

Keeping the peace with England was essential to the security of the Spanish Monarchy because in autumn 1574, while the Army of Flanders abandoned the siege of Leiden, a Turkish expeditionary force recaptured Tunis. Philip’s spirits sank even further. He began one rescript with a warning that ‘today I am in a foul mood and fit for nothing’, and when he read about unrest in some Castilian cities caused by the increased alcabalas he longed for death. ‘Everything seems about to fall apart: how I wish I could die, so as not to see what I fear.’ Upon opening two letters ‘to be placed in the king’s hands’ describing new problems, he exclaimed: ‘If this is not the end of the world, I think we must be very close to it; and, please God, let it be the end of the whole world, and not just the end of Christendom.’25

The road to ruin

Instead of the Apocalypse, the New Year brought the king a new problem: his brother. As soon as Don John heard that the Ottoman fleet had left Constantinople, he disobeyed Philip’s express orders to remain in Milan. As he explained to Margaret of Parma, his half-sister and closest confidante: ‘Everything is in a perilous state, my lady, although it is not entirely His Majesty’s fault’: the real problem was that their brother ‘allows people to govern his dominions who do not take responsibility for anything that does not immediately affect them’. As a result, ‘the money that takes so long to find is spent at the wrong time and the wrong place, with the result that it is wasted’. So, to save the situation, Don John decided to disobey his brother: ‘Without waiting any longer, I shall now go to Spain.’26

In a memorandum written in January 1575, shortly after his brother’s unexpected arrival, Philip lashed out at virtually everyone around him. ‘My head is so full of concerns and complaints from the people who are supposed to help me that I can scarcely contain myself. And all they do is raise fears and problems, as if I did not already know about them; and they provide no solutions, as if I were God and could provide them.’ And then ‘in comes my brother to tell me that nothing is getting done; and although he did not blame anyone, I was somewhat annoyed and I told him that nothing was getting done because there was nothing to do it with, and that we cannot do the impossible.’ Finally, ‘as I was writing this, they brought in this package from Juan de Ovando. Just consider: I am in no state to work out a reply, although I am sure there are some things here that require one. But I just can’t.’27

Ovando had become used to his master’s procrastination, but now his patience snapped. In March 1575 he sent a blistering analysis of how Philip had mismanaged his financial affairs. First, Ovando pointed to his own achievements over the previous year. ‘Although the Royal Treasury had reached a desperate state’, he had managed to raise and dispatch a million ducats to the Netherlands, and more than half a million to the fleet of the late Pedro Menéndez, almost another million to Italy, and loans worth over two million more for the campaigns under way. Ovando now contrasted these concrete achievements with the king’s inaction, ‘because you did not trust me, or any of your fiscal officers’, and then he listed the various concrete proposals that he had made, only to have the king reject all of them. Ovando also denounced the relentless rise in the interest rates demanded by the king’s bankers, noting that firms that had made loans in the 1560s at 8 per cent annually now demanded 16 per cent and sometimes more. He concluded that only a Default Decree could end the vicious circle.28

Before Philip could digest all this, news arrived that the Ottoman fleet was about to mount another campaign in the western Mediterranean. Just as in the previous year, he ordered his fleet to maintain a defensive posture, and impressed on Don John that if he decided to attack Tunis and Bizerta again, it must be to destroy them: under no circumstances should they be recaptured and garrisoned. Philip also ordered Requesens to adopt a defensive posture in the Netherlands. He authorized formal negotiations with the rebels, approving in advance numerous political concessions. He forbade only discussion of religious matters.

So many difficult decisions left the king exhausted. According to Don John, ‘when I left court’ in spring 1575,

His Majesty was well, thanks be to God, but so tired by public affairs that you can see it in his face and his grey hair. I am very worried about him. The news from the court that I can share is certainly not good, because His Majesty has no one with whom he can relax, and so everyone is confused and our master is exhausted – and business is not dispatched with the same speed as at other times.

He did not exaggerate: Philip himself admitted that he felt ‘so tired’ that ‘I really don’t know how I survive’.29

Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, delegates representing the king, the prince of Orange and the States of Holland and Zeeland assembled in the town of Breda. No sooner had talks begun than Requesens noted that ‘rumours are circulating throughout this country that if we do not come to some agreement, a general revolution will break out’ – and, he gloomily predicted, ‘I have no hope that we can reach an agreement because we cannot grant them any of the religious concessions that they ask.’ Twelve weeks of discussion at Breda proved Requesens right. Just before he broke off the talks in July 1575, he wrote to a colleague: ‘If we were talking about a peace that could be settled by transferring four towns or four kingdoms’, a settlement could surely have been reached; ‘but since everything depends on religion’, peace was ideologically impossible. The war could not be won by conventional means, ‘with all the debts we have, and so many soldiers here whom we cannot demobilize without pay nor maintain without much money’. In short, ‘I do not know how we can carry on like this.’30

The conference at Breda proved an expensive error for the king. It strengthened the Dutch, because by agreeing to the talks Philip accorded his rebels a degree of recognition, while the experience of negotiating collectively increased their internal cohesion. Conversely, it weakened Spain, because the king’s soldiers continued to earn wages even though they did not fight. Above all, it made nonsense of a decision taken by Philip in December 1574: that he would issue the Default Decree advocated by Ovando only the following September – a nine-month delay explicitly designed to permit Requesens to make one more attempt to crush the rebellion. Delaying the start of operations by three months in order to hold abortive peace talks ruined this prospect, too.

Nevertheless, the king stuck to his original timetable. Although in May 1575 he admitted that ‘if the cost of the war [in the Netherlands] continues at its present level, we will not be able to sustain it, still it would be a great shame if, having spent so much, we lost any chance that spending a little more might recover everything’ – the classic argument of a superpower in difficulties.31 On 1 September 1575, however, he signed two documents: one froze the capital of all outstanding loan contracts worth between 15 and 20 million ducats (estimates varied wildly) and terminated all payments to his bankers; the other ordered the rigorous audit of all loans made since 1560 to detect any fraud. For a few more days the king delayed but (as he explained to his ambassador in Genoa, where many of his bankers were based), ‘although we have maintained secrecy about this, it has not been sufficient to prevent the bankers developing certain suspicions, which has caused much harm because they no longer want to negotiate with us or lend any more money’. On 15 September, printed copies of the decree went out to all revenue officers in Castile with orders to cease paying anything on ‘the warrants that we have granted to merchants and bankers with respect to the loans and transfers we have arranged with them’ and instead to send ‘whatever they were due, and anything else’ to the royal treasury.32

Initially, Philip was optimistic. He had ‘created a special room and put in it a number of strongboxes’ in the Alcázar of Madrid, ready to receive ‘all the revenues collected in all parts of the realm’ formerly assigned to paying loan interest; but others knew better. The Dutch rebels lit joyous bonfires and offered prayers of thanksgiving upon hearing of the decree; while Domingo de Zavala, an agent of Requesens at court, wearily explained to the king that even though he had managed to send to Antwerp a letter of exchange for 100,000 ducats, 150,000 more in silver coins by sea and a further 100,000 in gold coins via Italy, ‘all of that together will not suffice to keep the war going for a single month’. Everything will be lost, Zavala continued, ‘unless Your Majesty ceases to fund all other ventures and expenditures in order to concentrate’ on the Netherlands, ‘so that we can retain the provinces still loyal and shorten the war, because prolonging it will bring high costs and high risks’. In Antwerp, Requesens shared this pessimistic assessment, warning his brother in November 1575:

The Default Decree has dealt such a great blow to the Exchange here that no one in it has any credit … I cannot find a single penny, nor can I see how the king could send money here, even if he had it in abundance. Short of a miracle, the whole military machine will fall in ruins so rapidly that it is highly probable that I shall not have time to tell you about it.33

Sent to the Netherlands under protest and left without clear instructions, Requesens claimed that the decree had broken his heart. It certainly broke his health and he died suddenly on 5 March 1576. The loyal Netherlands provinces, and the 60,000 royal soldiers fighting there, therefore came under the authority of the council of State in Brussels, composed of men with little aptitude for fighting a war – let alone for handling an army on the verge of mutiny.

Philip could do little to help them. The Default Decree proved a disaster for his foreign enterprises: ‘It certainly has not led me out of my necessity,’ he lamented in March 1576, ‘rather I stand in greater need since I have no credit and cannot avail myself of anything except hard cash which cannot be collected quickly enough.’34 It also proved a domestic disaster. Philip’s principal financial adviser assured him that ‘ever since the publication [of the decree] all merchants lack credit and almost all trade in all commodities has ceased’ in Castile; while ‘nowhere, either within these kingdoms or beyond, can anyone find a large or small sum of money, unless they use coins, which is expensive and risky’. In addition, Mateo Vázquez reminded the king about ‘the great distress in which Your Majesty’s servants find themselves: it would break your heart to see how some of them are broken in spirit and ready to die of hunger’. The king’s reply revealed his desperation: ‘If God would only give us more time, we could deal with these issues, but with so little of it, we cannot do everything … Nothing could be worse than everything being in suspense like this.’35

Philip was wrong: there was indeed ‘something worse’. In July 1576, the Spanish veterans, some of whom could claim six years of back pay, launched a surprise attack on Aalst, a town fifteen miles west of Brussels, and sacked it – even though it had always remained loyal to Philip. News of this atrocity caused widespread outrage, and in an attempt to restore calm the council of State in Brussels declared the mutineers of Aalst to be rebels against God and the king who could be killed on sight. The council also authorized the States of the provinces still loyal to the king to raise troops for defence against the mutineers. Then in September some of the soldiers raised by the States of Brabant arrested all the councillors; and the following day the States summoned representatives of the other loyal provinces to meet and authorize talks with their former colleagues in Holland and Zeeland, and with the Spanish mutineers, about ending the war. Representatives of the various protagonists assembled at Ghent to negotiate a ceasefire, using the issues agreed upon at Breda the previous year as their starting point, and by late October 1576 they had agreed to the terms of a ceasefire, deferring to a meeting of the full States-General the resolution of outstanding religious and political issues. Until Philip agreed to ratify the Pacification of Ghent, and recall the hated Spanish troops, the States refused to recognize the authority of his new governor-general, Don John of Austria.