oriental

greens

—

A whole range of exciting oriental greens have gradually become available to gardeners in the West. Their subtle flavours when raw, crisp texture, lively colours and nutritional qualities make them valuable additions to the salad garden. Many are in their prime in autumn and early winter and, being fast growing, lend themselves to cut-and-come-again techniques. More recently, the popularity of ‘baby leaf’ salads has led to new varieties being developed – beautiful, pink-leaved forms in some cases, and delightfully frilly leaf forms in others.

The oriental greens are in the main cool-season crops, ideally suited to summer and early winter cultivation in temperate climates, though there are varieties for warmer and tropical climates. They generally make excellent winter crops under cover. Some of the mustards are very hardy.

Oriental brassicas must be grown in fertile soil, rich in organic matter, with plenty of moisture throughout growth. It is just not worth growing them in poor, dry soils. Ideally soil should be neutral or slightly alkaline, as clubroot can be a problem (see here). Soil fertility apart, a key factor in growing oriental brassicas is overcoming a tendency to bolt prematurely. This is caused by various interlocking factors, such as day length and low temperatures in the early stages of growth, and can be exacerbated by transplanting. For this reason be wary of buying oriental vegetable plants from garden centres early in the year: they are likely to bolt.

The problem scarcely arises with cut-and-come-again seedlings, as they are harvested young. However, when growing plants to maturity, the safest bet is to delay sowing until early summer – that is, after the longest day – and to protect plants if a sharp temperature drop is expected. Some varieties are more bolt-resistant than others. Late sowing means that oriental greens, which are fast-growing, can follow early harvests of potatoes, peas, beans or salads, making full use of garden space.

On the whole, oriental brassicas do not transplant well, so sow them either in situ or in modules. They tend to have shallow roots, so, unlike other brassicas, need to be watered frequently, but moderately, especially when nearing maturity. Mulching, with organic materials or plastic films, seems to be beneficial for these greens. Unless the soil is exceptionally fertile, growth can be boosted with liquid feeds during the growing season. Oriental brassicas are subject to the same pests and diseases as Western brassicas (see here). Caterpillars and slugs cause the most trouble (for control measures see here). Growing under fine nets is highly recommended.

While they are all superb cooked vegetables, the most suitable for salads are the mild flavoured greens, typified by Chinese cabbage and pak choi, and some of the mustards and flowering brassicas. All are excellent with Ginger and Sesame dressing (see here).

A major barrier to adopting oriental vegetables is their confusing names. Not only are plants known by several names, but the same names are used for different plants. Then, to overcome the difficulties in pronouncing the original names, misleading Westernized names have been coined. ‘Pak choi’, for example, is often called ‘celery mustard’ – yet it is neither celery nor mustard. I try to use the most sensible, or currently acceptable, name for each plant.

Chinese cabbage

Brassica rapa Pekinensis Group

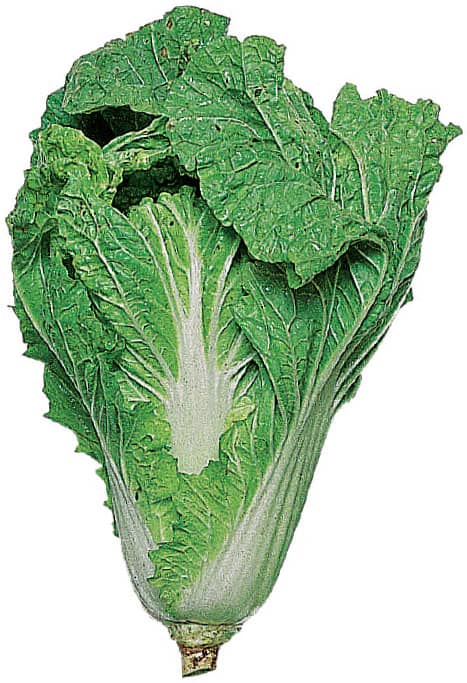

Popularly known as Chinese leaves, the hearted types of Chinese cabbage (known as Napa cabbage in the USA) form a barrel-shaped, rounded or tall cylindrical head of closely folded leaves, usually creamy to light green in colour, with a crinkled texture, prominent white veining and white midribs broadening out at the base. The tall cylindrical types are generally later and slower-maturing.

‘Loose- or semi-headed’ types are a distinct group that do not form hearts, used mainly as cut-and-come-again crops at the seedling and semi-mature stages. Varieties dubbed ‘fluffy tops’ have beautiful, butter-coloured centres of crêpe-like leaves, ideal for salad use. All Chinese cabbages are crisp-textured with a delicate flavour. They grow best at temperatures of 13–20°C/55–68°F. They tolerate light frost in the open, but with cut-and-come-again treatment plants remain productive under cover in the winter months. They have survived -10°C/14°F in my polytunnel. They are amongst the fastest growing of all leafy vegetables. In good conditions mature heads can be cut ten weeks after sowing, loose-headed types two to three weeks sooner, and seedlings four to five weeks after sowing.

Chinese cabbage is a very thirsty crop: a single plant may need as much as 22 litres/5 gallons of water during its growing period. Harvested Chinese cabbage heads will keep for several weeks in a fridge, frost-free cellar or shed.

Typical loose-headed Chinese cabbage

Typical tall-headed Chinese cabbage

Typical barrel-shaped Chinese cabbage

–––––

For the main late summer and autumn supplies

Sow early to late summer. Space plants about 30cm/12in apart.

–––––

For an earlier summer crop

Try sowing in late spring in a propagator, using bolt-resistant varieties; maintain a minimum temperature of 18°C/64°F for the first three weeks after germination. Protect plants with cloches or crop covers after planting.

–––––

For an autumn/early winter crop

Sow in late summer, transplanting under cover in early autumn. The plants may not have time to develop full heads. Plant either at standard spacing or about 12cm/5in apart – in which case cut the immature leaves when 71/2–10cm/3–4in high. Do not overcrowd autumn plants, as the leaves tend to rot in damp weather. Cut hearted plants 21/2cm/1in above the base and allow them to resprout during the winter. In spring let remaining plants run to seed: the colourful flowering shoots make a tender salad and are colourful too.

–––––

For cut-and-come-again seedlings

Use only loose-headed varieties, as hearting types often have rough, hairy leaves at seedling stage – though new, smoother-leaved varieties may be developed. Make the first sowings under cover in spring. Follow with outdoor sowings as soon as the soil is workable, giving protection if necessary. Continue outdoor sowings until late summer, and make final sowings under cover in early autumn. Cut seedlings as soon as they reach a useable size, leaving stems to resprout unless they have started to bolt.

–––––

Varieties

With modern breeding programmes the choice of varieties is constantly changing, and in practice, gardeners have to be guided by information in current seed catalogues.

F1 varieties tend to be of better quality and more reliable than older varieties. For headed Chinese cabbage, varieties described as compact, ‘mini’ or short are easier to grow than large varieties. All are excellent for salad use. For cut-and-come-again seedlings use loose headed types, sometimes listed as ‘bunching’ varieties; these include ‘Santo’ selections and ‘Tokyo Bekana’.

Pak choi

(bok choy/celery mustard) Brassica rapa Chinensis Group

The typical pak choi has smooth, shiny, somewhat rounded leaves, traditionally pale or dark green in colour but now with the addition of beautiful, reddish leaved varieties. The pronounced midribs merge into stems that swell out at the base into a characteristic, almost bulb-like butt. They are normally white-stemmed, but some varieties are a beautiful light green. The many types range from small, stocky varieties 71/2–10cm/3–4in high, to medium 15cm/6in-high varieties, to tall forms up to 45cm/18in high. (See also Rosette pak choi.) Varieties differ in their tolerance to heat and cold, but most only stand light frost. Like Chinese cabbage, they are excellent winter crops under cover. All parts, from seedling leaves to the flowering stems, are edible raw or cooked. Pak choi has a delightful fresh flavour, succulent texture, and to me, an irresistible, bonny appearance.

Pak choi is closely related to Chinese cabbage and grown in the same way (see here). For the headed crop, use slow-bolting varieties for the earliest sowings. Space small and squat varieties 12–15cm/5–6in apart, medium-sized varieties 18–23cm/7–9in apart and large types up to 45cm/18in apart. Allow up to ten weeks from sowing to harvest, though small heads are sometimes ready within six weeks of sowing. Leaves can be picked individually or the whole head cut, leaving the stump to resprout.

Cut-and-come-again seedling crops can be very productive. Depending on the season, the first cut of small leaves may be made within three weeks of sowing; it is sometimes possible to make two or three successive cuts.

Varieties As with Chinese cabbage, varieties are constantly changing and most give good results. The following are reliable, compact varieties, with good bolting resistance. ‘Baraku’ F1, ‘Choko’ F1, ‘Mei Qing Choi’ F1, ‘Shuko’ F1, ‘Summer Breeze’ F1, ‘Red Choi’ F1 (among many new, reddish-leaved varieties)

Typical green-stemmed pak choi

Rosette pak choi

(ta tsoi/tah tsai and similarly spelt names) Brassica rapa var. rosularis

This unique form has crinkled, rounded, blue-green leaves, which, although upright initially, in cool weather develop into a flat, extraordinarily symmetrical rosette head. It is hardier than other pak chois, and in well-drained soil may survive -10°C/14°F. This makes it a favourite in my winter potager. Its pronounced flavour is highly rated by the Chinese; the leaves are very decorative in salads.

Grow it as single plants or cut-and-come-again seedlings. It is slower-growing and somewhat less vigorous than other pak chois and prone to bolting from early sowings, so it is best to sow it from mid- to late summer. Like Chinese cabbage and pak choi, it can be transplanted under cover for an excellent-quality winter crop. Adjust spacing according to the size of the plant required: 15cm/6in apart for small, unrosetted heads; 30–40cm/12–16in apart, depending on variety, for large plants. Pick individual leaves as required, or cut across the head, encouraging it to resprout. As a baby leaves crop, it stands well over many weeks.

Varieties Mainly sold as ‘Tatsoi’ or ‘Tahtsai’; improved varieties include ‘Rozette’ F1

Rosette pak choi

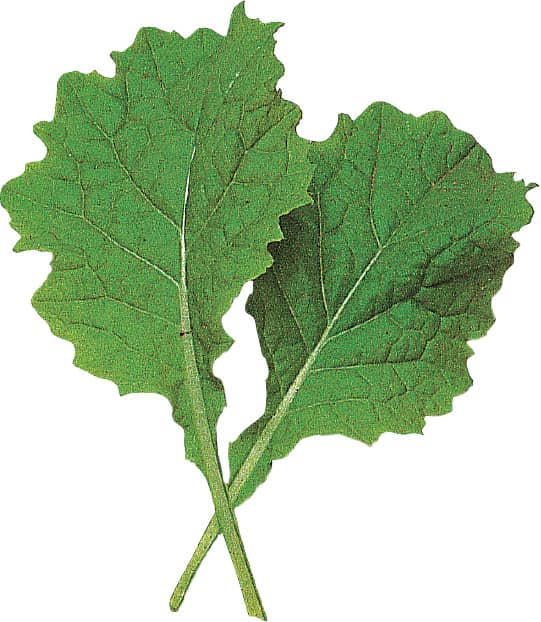

Komatsuna

(mustard spinach) Brassica rapa Perviridis Group

This extraodinarily diverse group of robust greens originated by crossing various brassicas. Most have large, glossy leaves, which radiate an aura of healthiness, especially in the winter months. They tolerate a wide range of climates, some being very hardy. They are less prone to bolting, pests and diseases than many oriental brassicas and, being vigorous, respond well to cut-and-come-again treatment at any stage. Essentially a vegetable for cooking, large mature leaves can be shredded for use in salads, but leaves from small plants and baby, cut-and-come-again seedling leaves are more suitable. The young flowering shoots are also very sweet and palateable in salads. Depending on variety, the flavour has hints of cabbage, spinach and mustard. They are said to be very nutritious.

For general cultivation, see Chinese cabbage. Sow outdoors from early to late summer, spacing plants 10cm/4in apart for harvesting young, or 30–35cm/12–14in apart, depending on variety, for large plants. For cut-and-come-again seedlings, start sowing in mid- to late winter under cover for a very early crop; sow outdoors from early spring to late summer, making a final sowing under cover in early autumn for a high-quality winter crop.

Plant breeders are developing varieties especially suited to baby leaf crops, including varieties with ruby red leaves.

The ‘Senposai’ hybrids are a group with a marked cabbage flavour, bred in Japan and widely used for seed sprouting. I found them a useful cut-and-come-again seedling crop for late summer in the open and winter under cover.

Varieties Older varieties: ‘Green Boy’ F1, ‘Komatsuna’, ‘Tendergreen’

Red leaved: ‘Comred’ F1. Watch out for new F1 hybrid varieties in seed catalogues.

Seedling leaves of komatsuna

Mizuna

(kyona, potherb mustard) Brassica rapa var. nipposinica

This beautiful Japanese brassica has glossy, serrated, dark green leaves, often 25cm/10in long. Mature plants can form bushy clumps well over 30cm/12in wide. It is an excellent plant for edging or infilling decorative potagers, and for various forms of intercropping. Mizuna tolerates high and low temperatures: if kept cropped it will survive about -10°C/14°F in the open. With its natural vigour and healthiness it responds well to cut-and-come-again techniques at every stage, and can remain productive over many months. The leaves have a mild mustard flavour. Mature and seedling leaves can be used in salads, the latter being daintier and more decorative. Young flowering shoots are also sweet and colourful in salads. Cultivate as komatsuna above. Sowings in hot weather are susceptible to flea beetle attacks.

Besides the more traditional, serrated leaved varieties, there are now broader-leaved varieties such as ‘Waido’, some very finely cut, feathery-leaved varieties, and red and reddish tinged leaved forms. See seed catalogues for what is currently available.

Broad-leaved mizuna greens

Finely serrated mizuna greens

Red mizuna greens

Mibuna greens

Brassica rapa var. nipposinica

Mizuna’s twin, mibuna, has narrow, strap-like leaves 30–45cm/12–18in long, which are less glossy and probably milder-flavoured than mizuna but add an interesting dimension to salads. Mature plants form handsome architectural clumps. It is less productive than mizuna and less hardy – surviving temperatures of about -6°C/21°F in the open. It is a cool-season crop and best value in the late summer/early winter period, in the open or under cover. For cultivation, see Mizuna. Currently ‘Green Spray’ F1 is the only named variety. The flowering shoots of both mibuna and mizuna can be used in salads.

Mibuna greens

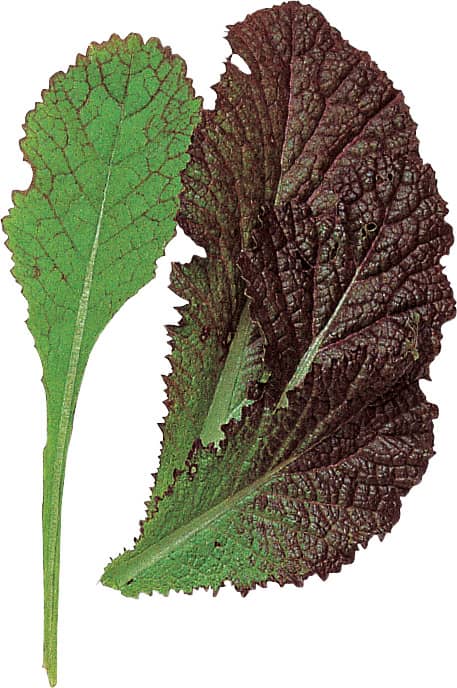

Mustards

Brassica juncea

This vast and rugged group of hardy vegetables has rather rough leaves with varying degrees of fiery flavour. They not only add a spicy zing to a salad, but also often a colourful and decorative element. Use them sparingly. Mature leaves can be shredded to moderate the flavour, which tends to intensify as plants age and run to seed. The flowering stems are edible too – again, approach them cautiously. Some time back I discovered, through serendipitous nibbling, that both the ordinary and flowering stems of the pickling or stem mustards have a delectable, almost sweet flavour – superb in salads. It may be necessary to peel the outer skin before use.

The main salad use of the oriental mustards is as ‘baby leaves’, and they feature prominently in the popular mixes now sold for stir-fries and salads. Look out for ‘spicy’ in the mixture names; ‘Bright and Spicy’, ‘Nice and Spicy’ etc. Because so many are hardy, they are particularly useful in winter months.

The mustards are slower growing than most oriental brassicas. They are mainly sown in mid-summer, in situ or in modules. For mature plants space them 25–40cm/10–16in apart, depending on variety and the size required. They can be planted under cover in late summer or early autumn for a more tender crop.

When grown as cut-and-come-again seedlings for baby leaf, early sowings are very liable to bolt, so sowings from mid-summer to late summer are recommended. Regrowth is less vigorous than in many seedling crops, but they will stand in reasonable condition for many weeks.

The varieties being used alone, or in mixtures for salads, come mainly from the mustard groups below.

‘Green in the Snow’ mustard

Purple-leaved mustards

–––––

Giant-leaved mustards

This group includes the handsome, purple-and red-tinged mustards, typical traditional varieties being ‘Red Giant’ and the slightly finer ‘Osaka Purple’. They are reasonably hardy, often acquiring deeper colours as temperatures lower. I saw them grown as seedling crops in summer in the Napa Valley in California, with the leaves cut for salads about 21/2cm/1in diameter. There are also green varieties, such as ‘Miike Giant’.

Possibly originating from the giant mustards and these smaller-leaved types, are exciting new varieties bred for baby leaf use. Some have beautifully coloured red leaves: ‘Red Dragon’ and ‘Red Lace’ are two currently available. Another decorative group are the ‘Frills’ varieties, with beautiful, serrated feathery leaves. There are red, green, and very light coloured forms. ‘Red Frills’, ‘Green Frills,’ ‘Golden Streak’, ‘Ruby Streak’, are some of these new varieties currently available, but the choice is constantly changing. Look out for them in current seed catalogues and in the seed mixtures. All are best eaten young in salads, though they can be stir-fried when larger.

–––––

Common or Indian mustards

There are many somewhat smaller-leaved, rugged and spicy mustards, sometimes labelled Common or Indian mustards. One of the best known is the serrated-leaved ‘Green in the Snow’ (Serifong, Xue li hong and assorted spellings). The Chinese name means ‘Red in the Snow’, indicating how hardy it is – though the leaves are, in fact, green! It can develop into a large plant, but for salads can be grown either as cut-and-come-again seedlings, or spaced 15–20cm/6–8in apart for small plants cut young before the leaves become too hot.

Another useful, though less hardy variety, is ‘Amsoi’, used in China as a pickling mustard. Pick young leaves and stems for use in salads; they have an interesting flavour.

The flowering brassicas

Brassica juncea

The flowering shoots of almost all oriental brassicas can be used raw in salads. Most are pleasantly sweet-flavoured, though mustards have a characteristic hot flavour. Pick shoots from mature plants when in bud, before the flowers open. The plants generally produce a succession of shoots.

The following are types traditionally cultivated primarily for their flowering stems. Plant breeders have been developing improved varieties with more substantial, and more succulent edible shoots, though few are listed by name in home gardeners’ catalogues. Where available, they can often be found under the general names below and are well worth growing.

–––––

Choy sum Brassica rapa var. parachinensis (often listed as flowering pak choi)

The standard green-stemmed type has yellow flowers, and is moderately hardy. Sow from early to late summer, in situ or in modules for transplanting, spacing plants 12–20cm/5–8in apart. Cut the shoots when 10cm/4in long.

The well-known purple form ‘Hon Tsai Tai’ (the Chinese name means red shoots), has purple flower and leaf stalks, with leaves varying from dark green to purple. It is quite hardy, surviving -5°C/23°F outdoors. Grow as above or space them up to 38cm/15in apart for large plants.

–––––

Edible oil seed rape Brassica rapa var. oleifera and B. r. var. utilis (sometimes listed as flowering Chinese cabbage)

Not to be confused with the ordinary oil seed rapes – but developed from them – are hybrid varieties with chunky, succulent stems, yellow flower buds, and pretty, crêpe-textured leaves. Some varieties are even used as cut flowers in Japan. Grow them like Choy sum (see here). They generally tolerate light frost and do well under cover in winter. ‘Shuka’ F1 is one of the newer varieties.

Edible oil seed rape leaves

–––––

Chinese broccoli (Chinese kale, Gai laan) Brassica oleracea var. algoglabra

This distinct, thick-stemmed, white-flowered brassica is appreciated for its exceptional flavour. While normally cooked, it can be used raw in salads, though the stems may need to be peeled before use. It tolerates several degrees of frost and does best from mid- to late summer sowings. Space plants 10–15cm/4–6in apart for harvesting whole when flowering shoots appear, or 25–38cm/10–15in for large plants, where individual shoots are picked over a longer period. ‘Green Lance’ F1 is one of the older varieties, ‘Kaibroc’ F1 a newer variety.

Oriental saladini

Oriental saladini was originally a mixture I created in 1991 with the seed company Suffolk Herbs to introduce Westerners to the wonderful diversity of oriental greens. The mixture included loose-headed Chinese cabbage, pak choi, komatsuna, mibuna, mizuna and purple mustard. The various ‘spicy green’ mixtures on the market can be used in the same way. Its main use is for cut-and-come-again seedlings for salads or stir-fries, though you can prick out or transplant individual plants and grow them on to maturity. Sow as for Chinese cabbage cut-and-come-again seedling crops, see here. Spring and early summer sowings may allow only one cut before the plants start to bolt: the most productive sowings are from mid-summer onwards. Make the last sowings under cover in early to mid-autumn for use in winter and early spring. Patches often seem to ‘thin themselves out’ after several cuttings, leaving just a few large plants. Oriental saladini can be sown in containers or spent compost bags.

Many of the oriental greens and salad mixtures listed today are variations on the ‘oriental saladini’ theme. They are excellent value for salad greens, often productive over several months.