April 2012:

One month before graduation

AS THE BUS MOVED SOUTH, Isaias and Daniel Nix played a trivia game on a cell phone. “Latvia!” Isaias called out, then spelled it. “L-A-T-V-I-A.”

They were taking a field trip to a FedEx hub—not the huge one at the Memphis airport where workers load and unload jets, but a truck hub across the state line in Olive Branch, Mississippi.

For many years, FedEx has been the biggest employer in the Memphis area. The city enjoys a central location, access to the Mississippi River, and major highway and railroad connections to the rest of the country. Even before the creation of FedEx in the 1970s, the city had long served as a distribution center. The goods have ranged from cotton and slaves in the nineteenth century to Chinese-made consumer products in the modern era. By the mid-2000s, cavernous, boxlike warehouses dotted the industrial landscape in the southern section of the city, and workers pulled items from shelves and made minor upgrades for customers—sewing monograms on Williams-Sonoma bedsheets, for instance. Many students had put on their best clothes for this trip because FedEx was hiring.

Margot Aleman from Streets Ministries rode on the bus with the students. Nothing unusual about this—if you attended any Kingsbury High School function and looked around, chances were you’d see Margot. She often hugged kids in the cafeteria as she had on the first day, she went to football games, and later in the year, she even went to the prom. She used her Spanish to interact with parents, calling them and sometimes visiting them at home. And she helped run the Streets Ministries events at the community center near the high school, including dances, small group meetings and parties.

She often tried to improve children’s lives in concrete ways, like helping them graduate from high school. Now Margot was paying attention to Isaias.

The bus arrived at the FedEx site, and in a conference room, one of the company’s employees asked the students, “How many are going to college?” Hands went up. Isaias didn’t raise his.

A recruiter said the company hired a lot of students as package handlers.

“What does a package handler actually do?” someone asked. The answer: package handlers unloaded trucks, then loaded them again, even in blazing-hot weather, and they did it for a starting wage of about $10.50 per hour.

The students left the room for a tour of the package sorting center. Margot walked alongside Isaias and talked with him about college.

“Whatever you think is best for you,” she said.

“Yeah,” he responded.

“The only reason we pester you guys on college is that it does open a lot of doors. However—however, I know people who have master’s degrees and they’re unhappy. But overall, a college degree will open up doors.”

The group entered a massive high-ceilinged space of blue-painted metal, conveyor belts and concrete floors. Nothing moved at this time of day. As the tour guide began his talk, Margot felt upset. Isaias had just told her he had made up his mind and never really wanted to go to college. “Freakin’ genius,” she muttered. She spoke not with sarcasm, but sadness.

As the end of the school year drew closer, Isaias’ decision to skip college had provoked concern among adults who cared about him, like Patricia Henderson and Margot Aleman. But otherwise, it hadn’t raised a big alarm among the Kingsbury staff, perhaps because many other students were doing far, far worse.

In April, Kingsbury principal Carlos Fuller unexpectedly called the seniors to the school auditorium. The loudspeakers played “Pomp and Circumstance.” The students’ names were called and they walked across the stage one by one. Isaias walked in this mock graduation, too, and he mimed accepting the diploma and pretended to pose for a picture.

Mr. Fuller celebrated with his students: “I present to you the graduating class of 2013!” Then he suddenly changed his tone. He told the students that many of them might not walk across the stage at the real graduation in a few weeks because they were failing. “I know the hard work I’ve put in for some of you guys. Begging. Pleading. Do what you got to do to get this diploma.” He pleaded again with the students—if you have bad grades, get with your teachers and make up the work.

“Don’t quit now!” he thundered from the stage, holding a microphone in his left hand and gesturing with his right. “In your second semester of your senior year, to quit! If you quit now, what do you truly expect to do for the rest of your life? You quit now, you’re gonna be a quitter forever!”

Guidance counselor Brooke Loeffler called the names of students who were failing classes. “I need to see all of you.” While Isaias and other successful students left, she handed out preliminary grade reports. One boy in the front row said, “I’m failing Tuminaro. Fuck!”

Ms. Loeffler counted a total of 101 kids who were failing one or more classes—roughly half of all seniors. Of those failing, 47 hadn’t shown up for the mock graduation ceremony. Clearly, something was going wrong. Dozens of students on the verge of graduation had apparently decided school just wasn’t worth it. What was happening?

It was hard to know the life circumstances of every senior. But some students probably had very good reasons to make school a low priority. Staffers said some Kingsbury students were dealing with extreme situations, like homelessness.

Coach Haidar told me about an African-American boy in his chemistry class some years earlier who was sleeping in an abandoned house. “I went to see, and I’m like ‘This is where you live?’ He’s like ‘Yeah.’” The teacher remembered the cold air blowing through an open window. The student had run away from home after fighting with his mother, whom Coach Haidar described as crazy. His father wasn’t around. Teachers quietly intervened in the student’s case, bringing him food and money. He eventually graduated.

Another teacher told me he’d brought a student home to live with him and his girlfriend after the student’s mom had thrown him out.

Some students lived in abusive homes. Early in the year, Eduardo Saggiante, the school interpreter, told me a girl was skipping school because her mother’s boyfriend was beating the mother and the girl was afraid to leave her alone. The mom also feared deportation. The interpreter said that James Anderson, the fatherly Memphis police officer assigned to Kingsbury, was going to help and that he, Eduardo, wanted to speak with the mother, too, and let her know that Memphis police don’t enforce immigration law.

Other circumstances explained the seniors’ absences. Immigrant kids got pulled out of school to interpret for parents. Teen mothers had to care for sick babies.

In one case, it appeared that a parent had pressured a teenager to leave school. The case involved a thin, friendly Hispanic eleventh grader who had helped the librarian, Marion Mathis, build the elaborate display she called the Bat Cave.

Visitors could walk into the library, duck through a low door in the wall, and enter a small room suffused with dim green light and the scent of the live trees that decorated a fake graveyard. Dozens of ghoulish objects crammed the space: skeletons, a gargoyle, a space alien in a casket, an electric-powered mummy woman rhythmically rocking a corpse baby.

Ms. Mathis loved monsters and saw them as underdogs. “When I read Beowulf, I always pull for Grendel,” she said. She found that kids loved monsters, too, especially when the kids came from troubled backgrounds. Before Ms. Mathis taught at Kingsbury, she’d taught at an alternative middle school for boys who had lived in unstable environments all their lives. Some had been raped. Ms. Mathis said writing about monsters helped them work through their feelings. “And they wrote the most beautiful, creative stories.” She said the process of building the Bat Cave taught students how to handle a project from start to finish, and that a related essay contest sharpened writing.

The eleventh grader’s class essays revealed a tough upbringing, with a father in prison and bouts of hunger. While others missed school, this boy showed up. He told Ms. Mathis he wanted to be a doctor.

In mid-October, the librarian found that the Bat Cave’s black plastic ceiling had collapsed, and she sent the teenager text messages asking him to help fix it. He said he might not come to school anymore.

I’m afraid ill have to be home schooled, he wrote in one message. I’ll work in the morning, 6a–4-5 pm and study in the afternoon. My mom can’t take all the house expenses by herself;(

In another message, he wrote:

No, Mrs. Mathis. I will actually be working full time in the first shift at a company and study in the afternoon. I sure this changes because i will definitely miss school sooo much.

Ms. Mathis knew that in this case, homeschooling could mean no schooling. The next day, she almost cried. “He was such a good student and I know he wanted to go to college.”

I never saw him at school again.1

For other students, immigration problems killed their motivation to study.

“It messes with your head,” said Jose Perez, the senior who wanted to join the Marines but was having difficulty because he’d been brought to the country illegally as an infant. As the year wore on, if he started to feel bad, or unmotivated, he’d simply leave school. Or he’d skip entire days to work construction. Other laborers asked why he bothered to go to school at all if he was just going to end up working with them.

Yet some of the seniors who skipped school didn’t face immigration problems. Apathy was widespread throughout the senior class, Ms. Loeffler said. “It’s not just with our undocumented students, it’s with all of our students.”

Rigo Navarro, the soccer goalie, had the legal immigration status that students like Jose Perez craved. Yet he skipped school, too, and now he was in serious academic trouble, failing both of the English courses he needed to graduate.

Earlier in the semester, I’d asked Rigo why he’d missed so many days recently. He gave a long string of explanations, each of which accounted for a few hours or a few days away from school: He’d eaten a big bag of chips and become sick. He’d had a flare-up of costochondritis, a painful condition of the chest wall. His mom didn’t drive and didn’t speak English, and when she got a new puppy, he had to help her go to the veterinarian’s office. He had to take a driver’s license test. One of his brothers was having car trouble. Rigo went with him to the junkyard to find a part but lost the key to his own car there. “It took me five hours to find it,” Rigo said. Then he went to Arkansas to do an estimate for a fence-building project and missed more hours of school. Oh, and he failed the driver’s license test and he’d have to take it again and miss another day of school.

Teachers sometimes grew impatient.

“Are you going to be here more now that you have soccer practice every day?” Corey VanHuystee, the assistant English teacher, asked Rigo back in January.

“Well, I’ve been sick,” Rigo said.

“You’ve been sick a lot,” the teacher said in a doubtful tone.

“It’s not my fault. I take care of a little baby.” (Rigo’s big family sometimes pressed him into babysitting duty.)

“Hmm … I know, but you need to be at school, too.”

Rigo wasn’t content to live like a typical high school student.

“One of my brothers in Mexico told me that I’m living a very adult life at a very young age,” Rigo said. The summer before his senior year, he’d thought about dropping out entirely and sticking with his construction job, where he said he was making between $1,500 and $2,000 per week. But Rigo said his employers told him that if he dropped out of school, he couldn’t keep the job.

After graduation, Rigo planned to go back to work for the same company. Down the road, he would study, too, probably drafting. “I don’t want to do a four-year college because I know how I am. And I’m gonna be honest. I like money.”

Rigo spent money on expensive shirts and luxury-brand belts as well as on cars and trucks. When he went out to eat with a friend, Rigo would usually pay.

Rigo would say later that he understood why adults would doubt his explanations for missing school. The way he was living—the hard work, the expensive clothes—wasn’t normal.

Rigo said other factors diminished his will to stay in school. Though deportations were relatively rare in the interior of the country, one of Rigo’s older brothers had been deported during Rigo’s junior year. Rigo’s father said it had happened after police in Arkansas found a small amount of cocaine in the truck the brother was driving, and though Rigo’s father said he had denied the cocaine was his, he was deported.

Rigo said that his brother had been a sort of father figure for him, and Rigo had slipped into a depression. Soccer injuries dampened his spirits, too.

Recruiters from the University of Memphis soccer team had spoken with Rigo earlier in his high school career about giving him an athletic scholarship. But Rigo lost contact with the recruiters during his senior year and assumed they were no longer interested. “When I found out I lost my scholarship, I basically gave up,” he said much later.

Rigo said that during his senior year, his parents rarely spoke with him about school. “They were like ‘He’s going to school,’ so they think I was doing good,” he said later. He felt his parents were too busy to pay him much attention, and he believed other Hispanic kids experienced the same thing. “So [the kids] end up doing whatever other students do, because they’re the ones giving the attention to them … I myself tried a few drugs, knowing that it was not the right thing, but my friends were doing it.”

Immigrant parents often believed they could help their children by working hard, yet that meant leaving many children unattended, researchers Carola and Marcelo Suárez-Orozco wrote in their 2001 book Children of Immigration. And many immigrant parents suffered from anxiety and depression, which made them emotionally unavailable. Parental absence made some children hyper-responsible. In other cases, absent parents resulted in depressed kids who were drawn to alternative family structures such as gangs, the researchers wrote.

Rigo’s father said that when he was raising Rigo’s older siblings, he’d been so busy earning money that he often had to miss time with them. But he said that by the time Rigo, his youngest, was growing up, the older siblings were contributing to the household income and he had more time, and he made an effort to pay attention to Rigo. He said he often went to watch Rigo’s soccer games. “Why? Because I wanted my son to see that I was interested in him.”

* * *

That spring, even one of the most supremely motivated students in the senior class was showing signs of apathy. “Estevon, wake up!” Coach Haidar said to the figure slouched forward on the desk. “Let’s go!”

This had been happening a lot lately. Estevon would sleep in class, or at least appear to sleep, and the chemistry teacher would tell him to sit up and pay attention. Coach Haidar said he believed Estevon was far more ambitious than he appeared. “He already read the whole book for his test. I guarantee you that. That’s the kind of person he is.” Estevon’s goals were changing. He said he’d withdrawn his application to Carnegie Mellon and was now aiming for Georgia Tech in Atlanta. “My sister lives there and if I get aid I can go there for free,” he said.

For Marion Mathis, the teacher and librarian who’d poured her energy into helping Estevon, this was bad news. She thought he was settling for something less than what he really wanted. “My first response was, ‘You’re going to regret this the rest of your life.’” Estevon was still awaiting results of one of the big grants he’d applied for, the Gates Millennium Scholars Program. And Ms. Mathis thought his fear of taking loans was irrational—with a good job, he could pay them off easily.

It was only later that Estevon told me what was going on inside his mind. “This year is so much stress. Like you can see the gray hair on my head. I’ve been stressing out a lot. Like, the second semester, I’ve been really depressed.” As he put it, he was in this “life dilemma,” and he and his mother had been arguing. And chemistry class was really, really hard. Estevon said he sometimes had a difficult time showing that he cared. But he did.

This was the downside to really trying. At Kingsbury and schools like it, making an effort meant subjecting yourself to anguish that few others would feel.

In March, Estevon learned he’d been named a finalist for the Gates Millennium Scholars Program. He felt happy. But his anxiety spiked the week before the ultimate winners were announced. He didn’t think he would get it. He thought to himself, “Oh my God, if I don’t get it, why did I even try?”

* * *

The decision to try or not try appeared pivotal. I wanted to see the government give legal immigration status to students like Mariana, Jose Perez and Isaias. But after spending time at Kingsbury, I knew legal status wasn’t an instant cure for all the challenges that young Hispanics faced. Just look at Rigo: he had legal immigration status but didn’t come to school. U.S. citizenship didn’t necessarily help either. White and African-American U.S.-born students dropped out at Kingsbury, too. I came to the conclusion that one factor often mattered more than immigration status or citizenship: motivation.

Elena Delevega agreed with me. “Clearly, I think so. I think motivation matters more. And I think that if you’re driven, you’re driven. But again, let’s not discount the effect of immigration status, in that if I think that I’ll never be able to get a job as anything else other than a maid, I may just lose my motivation.”

Born in Mexico, Ms. Delevega was a professor of social work at the University of Memphis. She pointed out that in a neighborhood like the one around Kingsbury High, many young people know little about the world outside. They won’t aspire to do anything different from what the people around them are doing. I’ve heard her argument formulated another way: you can’t be what you can’t see.2

So she tried to show them what they could be. She arranged for children at Kingsbury Elementary to go on a series of field trips to a local museum that would expose them to math and science and encourage them to pursue degrees in those fields. They got to do things like touch dead sharks.

“I want them to say, ‘This is cool, this is possible, and I want it for myself. And it’s going to take so much hard work. It doesn’t matter if I have to be up 13 hours sitting in front of a stupid computer screen. Because I want this like I’ve never wanted anything in my life. And I want this more than I want sex and more than I want a car and more than I want drugs. I want this more than I want to lounge around.’”

They have to think it’s possible before they’ll want it, though. “Because wanting something that is unattainable, it hurts a lot. And we are very good at avoiding pain.”

The apathy that I saw at Kingsbury was common across the country, said Daphna Oyserman, a psychologist at the University of Southern California who has dedicated her career to finding ways to boost motivation, especially among black and Hispanic kids.

“I’ve never been in an inner-city school where there weren’t lots of great teachers and where there weren’t a whole bunch of resources that were basically missing the mark,” she said. Teachers would stay to tutor, and no students would come. The public address system would tell students to get materials for a science project, and they wouldn’t do it.

She offered an explanation: school is hard, and students often don’t see any reason to push through obstacles. “No one works hard in school because this is the most fun thing and they can’t imagine a more fun thing to do. People work hard in school because they imagine how satisfied they’ll be when they attain a future self,” she said. “Kids often say they want to do well. But ‘school is boring, school is stupid.’ What they really mean is ‘I can think of a better thing to do with my time.’ Because when it’s hard I just think, ‘Oh well, it’s not for me.’” She said that’s not how American society talks about athletics.

“We have the ‘no pain no gain.’ ‘Missing all the shots that you don’t try to take.’ There’s all sorts of metaphors in sports. And weirdly, in academics where it really matters, we have no such metaphors. We act as though talent is a thing that descends upon us by the grace of God. And you either are smart or you work hard. No. You get smart by working hard.”

Ms. Oyserman tries to teach young people three key ideas: first, that when something is hard, it doesn’t mean it’s impossible, it means it’s important. Second, she tries to teach that academic success is something that’s consistent with ethnic or racial identity: for instance, that black and Hispanic kids do well in school.

“If you cue kids to think in that way, that ‘Oh, we care about school, I care about being a member of this group,’ then kids work harder in school.” She said kids who think of themselves as connected to both their group and to the broader society tend to do better, too—for instance, if they think of themselves as not just Mexican, but Mexican-American.

The third key idea she teaches is that the future isn’t far away, but intimately connected to the present—as she puts it, “The future is close.” She was working with the Lansing, Michigan, school district to set up bank accounts for students to save for college, starting in kindergarten. They couldn’t save enough money to cover the whole cost, but she hopes they will start thinking of themselves as people with futures. “So if I’m going to have a future, maybe I should also do my homework now.”

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Education asked researchers to submit grant proposals on how to “scale up” psychological interventions to improve motivation.

Ms. Oyserman and colleagues won a $2.7 million grant to develop a computer game that teaches ideas like “If it’s hard, it means it’s important” and test the game among middle and high school students in Colorado to see if it leads to improvements in outcomes such as grades and attendance.

Many other researchers around the country recognize the importance of student motivation and are trying to identify the best ways to boost it. As of this writing, there is no consensus on how to do this, and not even a standard language to use. Some speak of “non-cognitive factors,” others “grit” or “mindset.” I hope the researchers will figure out which motivation interventions really work. If that happens, I’d like to see the government encourage schools to put the interventions into practice on a broad scale. Otherwise, intriguing results might sit unused for years, and thousands of students will slide through their school days in a cloud of apathy. And adults will still be standing in front of high school seniors and begging them to please, please, please do some work.

* * *

Rigo finally found a subject that motivated him. One afternoon in April, he walked to the front of the seventh-period English classroom, looking sharp in a pink dress shirt. “Hello, class, my name is Rigoberto Navarro. My capstone project is on cartels.”

Speaking without notes, he launched into a presentation on Mexican drug-trafficking organizations. He flashed images onto the screen: Chapo Guzman, head of the Sinaloa Cartel. Smuggling methods, including a submarine.

Then Rigo warned that he was about to show some gruesome pictures. After a pause, he went on and displayed photos that showed a pile of drugs and a pile of money.

“Have you ever wondered what is between these two pictures? How they turn drugs into tons of money? Here’s the answer. Death.” Rigo proceeded to display photos of the bloody results of fights between cartels.

One image showed a bullet-riddled pile of corpses, people shot dead at a party. The next images showed horribly mutilated bodies. Rigo said he’d decided to spare the class the video of a guy getting his throat cut with a chainsaw. Mexico’s cartels were fighting a bloody war against one another and the government, and Mexico’s rule of law was so weak that most homicides weren’t even investigated.

Rigo wrapped up. A student asked him why he picked this topic. “As a Hispanic, I care about my country,” he said. “This is what happens daily in my country.” He also said one of his brothers had dealt drugs. Rigo’s father later confirmed this and said the brother had served time in prison for it.

Another question from the class: “Would you ever consider becoming a drug dealer?”

“To be honest, yes, I did,” Rigo said in class.

Rigo told me later that a man named Rene used to work for his family and then left. Later, Rene’s associates asked Rigo to help them. “And when I was like in need of money, they were like ‘Well, I can’t lend you money, but I can make you get fast money by taking basically drugs to Jonesboro,’” Rigo said, referring to a town across the river in Arkansas. “And since my brothers were working in Jonesboro, [the men said] it will make it seem like you’re just visiting your brothers.”

Drug-trafficking organizations prized Memphis for its transportation links just as legitimate companies did. As far back as the 1930s, the city had served as a distribution center for illegal narcotics, and as Mexican drug-trafficking organizations began to dominate the business, they worked in Memphis, too.3 Money from drug buyers in Memphis and cities like it was shipped to Mexico, where it lined traffickers’ pockets and covered costs ranging from bribing officials to hiring torturers.

So did Rigo agree to drive the drugs to Jonesboro?

“I decided not to,” he said. “It was so tempting. I won’t lie.”

He said no for two reasons. One, he didn’t have a car. “And two, I was with Mariana back then so I talked to her and she straightened me up. She made me decide between that and her.”

Mariana confirmed the conversation, though she said they’d already broken up at that point. “I was very against it. I let him know.” She opposed any illegal activity, and she thought it was wrong that anyone would ask an underage person to do such things.

The man Rigo’s family knew, 36-year-old Rene Hernandez, was one of four men arrested on April 1 of Rigo’s senior year when Memphis police officers raided a house on Reenie Street, about two miles north of Kingsbury High. The newspaper said police found a gun, Xanax pills, $170,000 in cash and marijuana bricks the size of paving stones: 2,100 pounds in all. Rene Hernandez later pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 33 months in federal prison.4

To conclude his presentation, Rigo showed the class elaborate dioramas he had built to illustrate the drug-trafficking business. Rigo cared about the issue, and it showed. “Your project is amazing, Rigo,” Mr. Tuminaro said.

Even though Rigo had missed so much class, Mr. Tuminaro offered him a chance to redeem himself. He could take oral exams for both English 3 and English 4.

Mr. Tuminaro knew something about giving extra chances to students who’d made mistakes. He only had to look at his own history.

As a teenager growing up in Poughkeepsie, New York, Mr. Tuminaro had thought that what he was learning in school was stupid and boring. He figured out a way to slack off for nine months of the year: he failed his regular classes and went to summer school, which lasted only two months or so and was much easier, since practically all he had to do to get an A was show up.

“Remember, that’s the problem with our school system,” he said. “Kids don’t get punished for failing. School systems and teachers do. They lose their funding, people lose their jobs … So summer school is not a kid’s last chance. Summer school is the school’s last chance.”

Around the time Mr. Tuminaro slogged to the end of high school, he began feeling disgusted with himself. “I’m about to face the world—I’m not prepared for it and I’m a bum, you know?” He started reading the Bible and committed himself to Jesus. He said he needed three attempts for the change to take hold, but it eventually did. A church helped him get into a college by writing a letter that said he had poor grades, but needed a second chance. One thing helped him: he had grown up middle class, and outside of school, he enjoyed reading. So when his second chance came, he was ready.

Mr. Tuminaro’s own experience and his years at Kingsbury had made him critical of the current education system. As Mr. Tuminaro saw it, teachers like him spent most of their time dealing with students who didn’t want to go to school.

He believed mandatory studies killed motivation. “You’re forcing people to sit through four years. They don’t know what it’s for. They don’t know what it’s about. They don’t think it has anything to do with them. And many of them are incapable of doing it because they don’t know the basics.”

His solution was radical: make education mandatory through the sixth grade only. After that, make it optional—and make it available only to those who had shown proficiency in basic math, reading and writing. If students didn’t have to go to school, they would realize how hard the real world was and want to study. And he believed schools should let students focus on what they wanted to learn by letting them choose a major, even in high school.

No one was planning to implement Mr. Tuminaro’s radical education reforms, of course, so he worked within the existing system. He said he joined the teaching profession to help students who were falling by the wayside, the ones who hated it and didn’t want to learn. Now, despite Mr. Tuminaro’s efforts, some of his students still couldn’t read. It made him feel he was failing.

One day I mentioned an idea to Mr. Tuminaro: that the students at Kingsbury weren’t just dealing with the question of what college to attend or what job to take, but also with the deeper question of the meaning and purpose of their lives.

Mr. Tuminaro agreed and recalled a quote he’d read somewhere: “I think he said, ‘As long as a man has a why, he can overcome any how.’”

As Mr. Tuminaro saw it, he had a why: to glorify God. He said that meant loving the students, even when they didn’t deserve it, even when they were bad, treating the unworthy as though they were worthy, just as Christ had done for him. “I have a why,” he said. “Which allows me to survive this job, which at times seems impossible.”

* * *

Rigo could have spent the next several days cramming for the make-or-break tests. Instead, he decided to travel to Florida with one of his brothers to work on a home-remodeling job and talk with an employer who had an office there. The employer might hire him for the summer on a construction job in Tennessee.

Once again, Rigo would miss several days of school. But he expected he’d have time to study. “It’s gonna be eat, work and study. And when I come back, I know for sure I’ll ace it.”

* * *

That April, Estevon Odria obsessively followed news about the Gates Millennium Scholars Program on a Facebook page for applicants. A friend from Nashville won the scholarship, and Estevon felt angry, almost as though that student had taken Estevon’s slot.

Based on the Facebook postings and the timing of the last round of letters announcing finalists, Estevon figured that his envelope would arrive on Thursday, April 18. The night before, he didn’t sleep, drinking coffee and walking around in circles in his room with the blue walls and the hardwood floor and the crucifix on the dresser.

After school, he grabbed a friend and insisted he come with him to the mailbox for emotional support. They made their way to the white house where Estevon lived, near a fence with gang graffiti. From the pictures online, Estevon knew exactly what an acceptance letter would look like.

He opened the mailbox.

* * *

On the afternoon of April 19, Isaias was dying of nerves for another reason. In a few hours, he would play keyboard with a new rock band, Los Psychosis. It would mark the first time he’d joined the band in public. They would play on the sidewalk during an art festival in midtown Memphis, not far from the school. Hundreds of people would walk by and hear them for a few seconds at least, or longer if they stopped and listened.

Dennis had been the first of the Ramos brothers to get into rock music, and in a way, it had changed the course of his life. He’d always been different from other kids. In middle school, he was bullied, and he looked for a way to fit in. He gravitated toward a group of boys from Mexico, El Salvador and Honduras who dressed up like gangsters, brought cigarettes to school, drank and smoked marijuana. Dennis’ father remembers him coming home with a pair of saggy, gangster-style shorts. He told Dennis they made him look like a woman, and Dennis didn’t want to wear them anymore.

They argued about boundaries. Dennis wanted to go out and party and drive around, and why wouldn’t his parents let him? His father remembered telling him, “Go ahead, I won’t stop you.” But he warned that if one day Dennis landed in jail, he wouldn’t bail him out. Jail was more than an abstract possibility. Dennis remembered that one of the other kids had been caught by the police with a gun and was sentenced to house arrest.

Then Dennis joined JROTC and felt proud of the uniform, and he met a new friend named Jonathan, a rock kid from Mexico City. Rock music enjoyed a strong following in Mexico—when Eduardo Saggiante, the school interpreter, was growing up, for instance, he wore black clothes and listened to heavy metal. Mario, Isaias and Dennis’ father, had been a fan of Led Zeppelin.

Dennis liked Jonathan, this cool kid who spoke Spanish with a city accent, and he drifted away from the wannabe criminals. Their friendship led Dennis to another rock kid who’d been bullied for being different, Javi Arcega. They started playing together, and Isaias came along to practices and shows. Isaias played the drums in a bar, even though he was only 13 at the time. Javi loved The Cramps, a band that had begun in the 1970s and had recorded in Memphis. The Cramps played a weird mix of rockabilly and punk and wore strange costumes onstage.5 Javi even got the band’s name tattooed on the inside of his right arm.

Javi wanted to play like The Cramps, but Dennis and Isaias didn’t. One day the Ramos brothers came over to the practice space, collected their things and left. A few years later, Javi ran into Dennis and his parents at a furniture store, which led to a restart of the friendship and eventually to Javi inviting them to play music together. Javi now was 22, the same age as Dennis, but bony, and a sad look would sometimes come into his dark eyes.

Javi explained the origin of the band’s name, Los Psychosis: “Well, psychosis is sort of like a disorder and that’s how I feel a lot of the time,” he said. “That’s how a lot of people feel when they listen to music.” He also mentioned the famous Mexican wrestler named Psichosis.

That spring they began practicing together at Javi’s house, a duplex where they would walk through a living room full of vinyl records and packages of diapers and climb a ladder into an attic practice space that was decorated with posters of Jose Feliciano and Tav Falco–Panther Burns. They rehearsed a set of songs that Javi had written, playing so loudly that the neighbors sometimes called the police.

Javi’s young wife, Stephanie Avila, had recently given birth to their daughter, Melody. Stephanie liked rock music, too, and the baby had been hearing it since she was in the womb. Javi sang and played lead guitar, Dennis played bass, and Isaias played keyboard.

On the afternoon of the show, Dennis steered his tan pickup truck with the Darwin fish onto Broad Avenue, an industrial neighborhood a short distance from Kingsbury High. The neighborhood was coming to life again as a center for the visual arts. Small galleries and shops lined the street, and the arts festival was already getting into full swing as the band members began placing their equipment in a narrow sidewalk space between the front of the Broadway Pizza shop and the parked cars.

They stretched a handmade banner spelling out the words “Los Psychosis” on the wall outside the shop and found an empty paint can to collect tips.

“If they ask, we’re Polish,” Isaias said.

Javi the lead singer agreed. “We just spend a lot of time in the sun.”

The fourth member of the band was Tommy Fletcher, a 35-year-old drummer with tattoos on his upper arms. One tattoo showed the Grim Reaper and the words “Some die young.” Tonight, Tommy was wearing a black t-shirt that had a picture of a gun and the words “Welcome to Memphis. Duck Mother Fucker.” Tommy was white and said they should introduce themselves as “vegetable soup.” “Three beans and a cracker from Memphis, Tennessee.”

As the sun set behind a nearby water tower, they began their first set, making the concrete sidewalk shake. Tommy’s sticks flew on the drums with professional fury. Isaias threw chords into the keyboard and Dennis rocked slightly as he played bass. Javi sang about bluesman Robert Johnson at the crossroads: “Papa Legba knows me well and is gonna take my soul away / away, away, away, away to misery.”

Herb Levy, who had taught Isaias in biology the year before, stopped and watched, and his little son dropped money into the paint bucket. One woman walked out of the pizza shop with her fingers in her ears. Most people simply passed by. But the music drew some punk rock fans, several of them white and fortyish, and they stopped and listened, rapt.

Night fell and a group of new fans stuck around for the band’s next set. For the second time that evening, the band played “Violent Sunset,” a song with a slow oom-pah-pah beat, like in norteña music. “Take me by your scaly hands!” Javi sang as he strummed the electric guitar. “Take me to Cairo and show me your sorrow. Hidden castles in the moon / We shall be there singing lonely tunes / But now … Now you know where I’ll be! At the end of valley—and that’s where I’ll beeeeeeee…” He drew out the last syllable as Tommy delivered a final drum flurry.

(Photo by Daniel Connolly)

The band neared the end of the set. Javi took a swig of amber liquid from a big bottle, then passed it to Tommy, who did the same. “Okay, one more time before we go,” Javi said, his voice reverberating over the microphone. “My name is Javi. This is Dennis. This is ‘No Mas’ Tomas,” he said, pointing to the drummer.

Javi turned to Isaias at the keyboard. “We got Chay on keys. Look at him, he’s still wearing his school uniform!” Sure enough, Isaias was wearing tan pants and a white shirt. As the small crowd cheered and laughed, he spread out his arms wide in a shrugging acknowledgment. “This guy right here, he’s about to graduate from high school,” Javi continued. “Congratulations.”

Javi hadn’t finished high school himself. He said he’d clashed with his Mexican immigrant parents and they threw him out of the house. He moved to a friend’s house and had to get a job. He returned once more to Kingsbury High to turn in his books and quit.

Now Javi began to sing. “Do the late night rock / at a horror house!”

The little knot of punk rock fans loved it and began to dance and whoop again. Javi fed off their energy as he strummed the guitar wildly, climbed onto an amplifier and hit Tommy’s cymbal with his head. He lived for moments like this. He earned money washing dishes, busing tables and helping in the kitchen in a sushi restaurant, but he thought about music all the time. He wanted Los Psychosis to become a huge success. As he saw it, music was his only chance to triumph at anything.

And then the show was over. The new fans stayed around for a while, and Javi invited them to come to his house, but it didn’t happen. One fan called “Good set, guys” as he left.

The musicians drove to Javi’s duplex. His wife, Stephanie, had watched part of the show, and as the band members brought in the amps and instruments, she rocked the baby in a little bouncing chair. “All of you guys look ten feet taller,” she said. “You’re all excited. High as hell.” Tommy passed pieces of equipment up a ladder and through a hole in the ceiling to Isaias, who pulled them into the attic practice space.

Dennis inventoried the contents of the paint bucket: “Hey, Tomas, it’s 29 dollars and a quarter.” Someone had thrown in a pair of sunglasses. One of the band members rolled the bills into a little cylinder and put a rubber band around it, and the musicians batted their earnings around the room like a toy.

* * *

Kingsbury held an end-of-year ceremony to honor its top students on Class Day, April 26, and in the slack time outside the auditorium before the event began, Jacklyn Martin, the English teacher, spoke with Isaias.

“I’ve got a band that’s playing together,” he said.

“How’s that going?”

“It’s going great. We had, like, three shows and we’re already big. We’re not big, but we played at the art walk on Broad Avenue.”

She said she’d seen the article about him in Falcon Express, the school newsletter. School librarian Marion Mathis had written the headline, which played on police jargon for “Be on the lookout”: “BOLO: Two Hispanic Males, Armed with ACT Scores!” Isaias and Estevon Odria held the school’s highest scores on the college entrance test, and the article said both planned to go to college. But now, Isaias told Ms. Martin, his situation had changed. He wasn’t going to college after all.

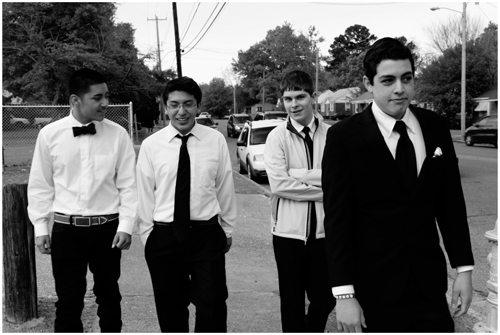

Walking to Class Day: (from left to right) Juan Avalos, Isaias, Daniel Nix and Ibrahim Elayan. (Photo by Daniel Connolly)

Isaias went off to join his friends, leaving Ms. Martin to process what he had said. She wondered if Isaias really wanted to skip college. She thought he was afraid to hope. And what a waste. With other students dying to go to college, it disturbed her to see Isaias shrug it off. How much of it was an emotional defense mechanism against the possibility that he couldn’t go? How much of it was him really being different?

The awards ceremony started, and Isaias got his first prize of the day for his performance in economics. A few minutes later, Ms. Martin went onstage and gave him her own award. “Lastly, I want to acknowledge the captain of our Knowledge Bowl team,” she said. “This is one of only two students to get a perfect score on the TCAP writing test last year. This student has also shown exceptional leadership skills with our Kingsbury International Club. That would be Isaias Ramos.”

Isaias strode forward again, and the students clapped and whooped as he climbed the steps. Some shouted his name. Moments later, Isaias came back to the stage yet again to accept a prize for participation in the school’s Super All-Stars club.

Then it was time for announcements of scholarship awards. Dressed in a black suit and with her mane of coiffed hair sticking out as usual, Ms. Henderson read a long list of names and dollar amounts that colleges and outside organizations had offered them, and the students cheered loudly.

“Daniel Nix—$22,000!”

“Cash Price—$58,000!”

“Breanna Thomas—$104,000!” The cheers grew louder.

“Adam Truong—two hundred…” she began, and the cheers drowned her out. Soon she’d reached the end of the list.

“I had to save the big one for last,” Ms. Henderson said. “Estevon Odria—please stand. For the Gates Millennium Scholarship to Carnegie Mellon—for $268,000!”

Huge cheers. Students jumped out of their wooden seats around Estevon. He stood up in his shirt and tie, his dark mustache neatly trimmed and dark hair cropped short, his expression serious.

When Estevon opened the mailbox after school a few days earlier, he saw a letter inside, a wide one. He eagerly clawed the packet out. He cried. He hugged his friend. He rushed into the house and told his grandmother, with her oxygen tube. He told Marion Mathis, and within minutes, Principal Fuller was sharing the news with assistant principal Norah Jones over his handheld radio. “Estevon got a full scholarship, bachelor’s and master’s at Carnegie Mellon!”

Estevon had withdrawn his Carnegie Mellon application. But he could reverse that step and still go.

Mr. Fuller read the news the next morning over the announcements as Estevon stood next to him at the microphone, shifting from side to side in the white school uniform shirt he’d only have to wear for a few more days.

Estevon was one of only three students named Gates Millennium Scholars within the entire Memphis City Schools system and one of 1,000 winners nationwide. The announcement letter said, “Your accomplishment is especially notable in context of the more than 54,000 students who applied, making this year’s the largest and most competitive group of candidates in the program’s history.”

Technically, the Gates Millennium Scholars Program didn’t pay the $268,000 amount that Ms. Henderson had cited at Class Day. The exact amount would depend on the financial aid package Carnegie Mellon offered. But in short, Estevon could go to one of the nation’s most prestigious universities without taking out loans.

Now he could even help his grandparents financially later in life. And if he went on to graduate school in a field such as computer science or engineering, the Gates program might help pay for that too.

He said he’d encourage younger students to apply. “It might seem scary at first but I know if I can get it, they can get it.”

“Just like, don’t give up hope in life, because if you work hard, it’s going to get you somewhere. And if I still didn’t get this scholarship, I know I would work it out somehow.”

The Gates Millennium Scholars Program aimed to help Hispanics and other minorities, yet the scholarship rules required them to be a “citizen, national or legal permanent resident of the United States.” That meant students like Isaias couldn’t get it. And the scholarship program wouldn’t last forever. A spokeswoman told me the program had been designed to fund 20,000 students, and in 2015, it was recruiting the last of them. The Gates program illustrated how a big commitment of dollars to education could change lives. I hope others will follow Bill Gates’ example.

At the Class Day ceremony, Estevon Odria’s name was last on the list. Patricia Henderson had read all the scholarship winners without mentioning Isaias.

Principal Carlos Fuller took the microphone to address the students once more before dismissal. “Guys, time is short now. We got exams, baccalaureate, graduation rehearsal. And if you forgive me, we gonna throw up the deuces.” In other words, we’ll say goodbye. The students cheered.

Mr. Fuller continued, mentioning the prize that Isaias had won in the audio production contest in Chattanooga. “He was a silver medalist, second in the state.” More cheers. Isaias hadn’t expected so much recognition. He had imagined going to Class Day as something like the Oscars award show, something that he would simply watch.

As the students left, Ms. Martin sought out Ms. Henderson, Isaias’ college counselor. In the counselor’s office, Ms. Martin told her Isaias was the best student she’d ever taught, hands down. She said she’d adopt him if she could. Wasn’t there some way he could go to college? Ms. Henderson said she didn’t see a solution. The young teacher began to cry.