May 2013:

Final days before graduation

THE CASE OF ISAIAS RAMOS gnawed at the conscience of Margot Aleman, the counselor from Streets Ministries. She had developed her own theory for Isaias’ reluctance to go to college: that his parents might want him to work in the family painting and remodeling business. “I don’t think his family knows how brilliant this kid is.” She’d never met them, and she realized she might be wrong.

Over a period of days, she planned an intervention. She told Isaias she wanted to speak with him and his parents at home, and he agreed. She convinced Isaias’ former English teacher and Knowledge Bowl coach Jacklyn Martin to come with her. She’d also bring along Jennifer Alejo, the counselor who specialized in finding scholarships for unauthorized immigrant students.

They set the date for May 15, after Isaias’ classes were over.

* * *

Was college worth it? Was it legitimate for adults to encourage Isaias to go? Across the country, people were questioning the value of higher education.

That skepticism was in sharp contrast to the scene that took place one day in August 2006, when then–Memphis City Schools superintendent Carol Johnson led thousands of employees at the FedExForum basketball arena in a chant: “EVERY CHILD! EVERY DAY! COLLEGE BOUND!” The superintendent said the words in other settings, too, and the school system itself referred to them as a “mantra.”1 As the school system moved toward adopting the phrases as its official slogan, critics attacked the message. “Don’t expect me to go out there and say ‘every child, every day, college bound,’” school board member Kenneth Whalum, Jr., told a reporter in 2007. “Everybody here knows it’s not true.” At the time, the district’s graduation rate stood at only 66.3 percent—its highest in years.

“I struggle with the message. I do,” the superintendent responded. “I am trying to raise the bar. If we don’t start, we will never get there.”

Mr. Whalum cast the only “no” vote when the school board voted 8–1 to adopt the slogan as its official brand. The system launched an accompanying advertising campaign. A news release clarified that “college bound” didn’t necessarily mean a four-year college, “but includes students who attend a two-year community or technical school, a trade school or other fields including the arts and music.”

Then in June 2007, the superintendent announced she was leaving Memphis to become head of public schools in Boston. The following year, a new superintendent, Kriner Cash, quietly replaced the “college bound” slogan without a school board vote. Now the slogan was “Breakthrough Leadership. Breakthrough Results.”

Around the time Isaias was finishing high school, news stories abounded of “boomerang kids” graduating from universities and moving back in with their parents, burdened with student loan debt and struggling to find work. Some young people were even living in homeless shelters, including many with college credits or work histories, The New York Times reported in a December 2012 story.2 Workers aged 18 to 24 had the highest unemployment rates of all adults.

Observers at The Wall Street Journal and elsewhere began to point to alternative careers in fields like welding, where a determined worker could earn more than $100,000 per year.3

Such middle-skilled jobs offered high salaries and seemed to make a lot of sense in the context of Kingsbury. In January, a bus carrying 21 Kingsbury students pulled up outside a drab brown building in downtown Memphis, the local campus of a state trade school called Tennessee Technology Center. Perhaps the biggest evangelist of practical training the Kingsbury students met that day was Ed York, instructor for HVAC, or heating, ventilation and air conditioning. With obvious pride, Mr. York showed the Kingsbury students the old refrigerators and ice machines that his trainees learned to fix. He said every grocery store, convenience store and restaurant needed these machines, and the people who repaired them could earn $20 to $30 per hour. Or students could specialize in repairing walk-in freezers. “They call you, they’ve got $30,000 worth of food in those walk-in freezers. So when they call you, they don’t care what it costs! They just want it fixed. So if you can fix it, you can make a lot of money.” Or they could fix air conditioners and run around all summer taking calls, making as much money as they wanted.

For some Kingsbury students, this wasn’t their first exposure to a trade. The vocational center near the high school, where Isaias did his audio recording class, also trained students in welding and other hands-on courses like small engine repair and cosmetology.

Now, the HVAC instructor was letting the students imagine what practical training could offer: mastery of a craft, pride, financial independence. And such training could appeal to the many Kingsbury students who didn’t care about academics. They wouldn’t have to read thick books and write essays. “And it’s only a year and a half,” guidance counselor Brooke Loeffler said as the tour group left the building. “You don’t have to commit a year to remedial classes and another four to five years to get your bachelor’s.”

Only 32 percent of Americans had a college degree in 2013, according to Census data, and among Hispanics it was 15 percent. Isaias knew few people who’d gone to college. In his family, the only one he could name when we spoke that April was a cousin in Mexico, but Isaias said she hadn’t finished. Outside his family, the only friend he could think of who was in college was Tommy Nguyen’s girlfriend, a student at Christian Brothers, but now Isaias didn’t talk with her much. It’s notable that both the people he named were young women—indeed, female high school graduates were more likely to enroll immediately in college than males. The gender gap in college enrollment had increased in the general population and especially among African-Americans and Hispanics.4

For Isaias, painting and remodeling in the family business could accomplish much the same as an HVAC job: money, independence, a sense of purpose.

Viewed in this context, his skepticism about college was understandable. Yet one small incident illustrated some of the risks of choosing a career in the family business. Isaias was installing drywall with his father and Dennis in the storeroom of a house one cold day in his senior year when he got a splinter embedded in his hand. He tried sucking it out, and said, “Ya la rompí”—I already broke it. Then he took a piece of duct tape, laid it against the splinter embedded in the skin, and tried to pull it out that way.

It was a tiny injury and quickly forgotten, but one that illustrated the risks in the job. He and Dennis sometimes climbed ladders, and a bad fall could lead to injury, medical bills and lost work.

In the Ramos family, only young Dustin, the citizen, had health insurance. For minor ailments, the Ramos family relied on traditional herbal remedies that Mario had learned from his mother. When someone had a more serious illness, they’d pay to visit a for-profit clinic called Healthy Life that catered to Hispanics.5

Of course, traditional remedies and clinic visits couldn’t always prevent something from going catastrophically wrong on the job. Hispanic laborers had the highest rates of workplace deaths among major ethnic and racial groups, probably because they did dangerous jobs, and they and their bosses sometimes disregarded safety measures.6

When Isaias and Magaly toured the library at Rhodes College, they doubtless had no idea that a man had fallen to his death while building it. The college memorialized him with a plaque. It read:

IN MEMORY OF

FRANCISCO JAVIER HERNANDEZ

OF

SAN FRANCISCO DE RINCON, MÉXICO

1958–2004

CARPENTER FOR THE PAUL BARRET, JR. LIBRARY

“EN LA CASA DE MI PADRE MUCHAS MORADAS HAY.”

In my father’s house there are many dwellings.

A short time after Isaias’ senior year, economists from the Federal Reserve of New York took a fresh look at the value of college: Given rising tuition for college, heavy student loan debt, and lower wages for college graduates, did investing in a degree still make sense? In dollar terms, the answer was a clear yes. Workers with a bachelor’s degree would, on average, earn far more over the course of their lifetime than those with only a high school diploma—to be precise, $1 million more.7 The lifetime advantage for those with an associate’s degree was smaller, but still significant: $325,000.

Yes, it was true that college graduates had trouble finding good jobs and that their wages had declined. But for less-educated workers, the problems were even worse. The researchers wrote, “Investing in a college degree may be more important than ever before because those who fail to do so are falling further and further behind.”

There were some risks. Going to college for a while and dropping out—as almost all Southwest Tennessee Community College students did—generally didn’t help students much, the Federal Reserve Bank researchers wrote.

The presence or absence of a college degree was correlated with a wide range of other successes, too. People with bachelor’s degrees were far more likely to marry and remain married, and less likely to have children out of wedlock.8

People with college degrees also tended to live longer, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control.9 For instance, consider a 25-year-old man living in 2006. He could expect to live to 72 if he dropped out of high school, to 76 if he finished, and to 81 if he had a bachelor’s degree or higher. A 25-year-old woman who dropped out of high school could expect to live to 77, whereas a college-educated woman could expect to live to 85.

“Highly educated people tend to have healthier behaviors, avoid unhealthy ones and have more access to medical care when they need it,” the report’s lead author said, adding that poor people sometimes live in communities with less access to healthy foods and places to exercise.

And this is to say nothing of the other benefits of higher education: its value in preparing people to participate in a democracy, or the intellectual joy of understanding the world and learning new things—a joy that Isaias appeared far more likely to experience than would most of his peers.

* * *

That May, Isaias’ father Mario discussed the value of college, too, relating a recent case he’d heard from back home in Santa Maria Asunción.

“We know a girl who studied political science and had problems when she finished. They’re paying her 1,500 pesos every 15 days.” That was about $125. “Imagine,” Mario said. “That’s ridiculous.”

He and Cristina were talking with Mariana Hernandez’s parents at a special banquet that Kingsbury was hosting to honor the senior class’s top ten graduates. Isaias and his parents arrived late, and Isaias explained that they’d had to work. They had all dressed up for the occasion, and they took seats at a table with the Hernandez family. The parents had never met before, and they talked about their jobs and the climate and populations of their hometowns in Mexico, and Mario shared the story about the college graduate they knew.

Each student was allowed to bring guests, but only Isaias, Mariana, Ibrahim Elayan and Breanna Thomas had brought a parent. Leonard Duarte, the valedictorian, came alone. So did Juan Avalos. Estevon Odria came with Marion Mathis, the librarian and teacher who had helped him with his applications. Tommy Nguyen brought his girlfriend. Jason Doan didn’t come.

Adam Truong was accompanied by his sister, but not his mother. Adam later said it didn’t bother him that his mother didn’t come to these events. He thought she wanted to be there, but she needed to earn money at the nail salon. She did come a few days later, when he graduated second in his class.

They finished eating, the ceremony started, and the English teacher, Jinger Griner, invited the students up one by one, gave them a plaque and said a few words about each of them. When it was Estevon’s turn, he held up the plaque so it partially covered his face, and Principal Fuller smiled as Ms. Griner described Estevon’s college success that year.

“So I’m very excited for Estevon,” she said. “And I hope he doesn’t forget Kingsbury.”

“I won’t. I’ll e-mail you,” Estevon said.

“You’ll e-mail me?”

“I’ll send you some soup.”

If Ms. Griner had been in her classroom, she might have added this comment to her running list of Estevon’s odd sayings. But now she simply said, “Some soup? Okay. Good job, Estevon!” Everyone laughed and applauded.

* * *

A few nights later, Isaias and the band pounded out “Late Night Rockin’” again, the song that had closed out the show at Broad Avenue in April. Only this time, almost no one was listening. They were playing in a mostly empty, dimly lit bar called Murphy’s on a Thursday night, opening for the group Coma in Algiers, which had come from Austin, Texas.

The set ended into sudden dead silence. Through the smoky, neon-lit air, Tommy the drummer called out to a man in the bar. “Don’t worry, we’ll be the audience in just a minute.” The man replied, “We’ll be the band.”

“I don’t know where everybody went, man,” Tommy said. The band members started packing up their equipment and carrying it outside. Isaias thought it was their best-sounding show to date. He marveled that the members of Coma in Algiers had come from so far away. “Those guys are from Texas! That’s crazy.” Isaias wanted to stay and told Dennis, “Let’s be the audience.” Dennis was reluctant. “I got to go to work tomorrow.”

“Just for a second at least,” Isaias said. “I’m going in.”

He went back inside and took a seat at a table facing the stage. Dennis followed and took a seat at the bar. Tomorrow, Isaias would go to Kingsbury High School for the last time. As a senior, he had the right to wrap up school a few days earlier than everyone else, and he would take care of final details. And that would be it. No more Kingsbury High—and for that matter, no more school, period.

As we sat there in the bar, I asked Isaias how he felt. “I don’t know. I feel like I’m going to miss it. I don’t know when else I’m going to go to an institution of knowledge like that.” He said he realized that many people who’d been part of his life wouldn’t be there anymore. Onstage, the members of Coma in Algiers began to warm up.

Isaias said he would miss his biology class from last year. He would miss calculus. Maybe he’d catch glimpses of it from Magaly’s learning, but he wouldn’t study it himself. He wouldn’t read literature in class. “I loved Macbeth when we read it, absolutely loved it. One of my favorite stories.” Then he thought of people. “I’m gonna miss Ms. Wilks. I’m gonna miss Ms. Martin. Ms. Dowda. Mr. Levy. Ms. Griner. It’s just sad.”

I had never seen Isaias cry, but now he seemed close. “Even though I’m not going anywhere, it still feels like I’m going to be so far away. Like no matter what, I’m never going to be there anymore. I’m not gonna be there again.” He paused. “It’s a happy sad.”

Around the end of the year, the students in the Advanced Placement Chemistry class took their national test. The tests were scored from one through five. A score of three or better could get them college credit.

The results came back months later, during the summer. Unfortunately, none of the students earned better than a two—not even Magaly Cruz, Mariana Hernandez, Leonard Duarte or Adam Truong. Several of them, like Estevon Odria, had scored high on their other standardized tests.

Coach Haidar was surprised. “They came out feeling good about it. ‘Test seems easy to us.’” Still, he took it in stride. It was his first year teaching Advanced Placement Chemistry, and he figured it would take three to five years to really get the program going. And he thought the course would still help the students in college chemistry.

“When they go to school, to college and sit in the class, they’re gonna shake their heads. ‘We’ve done all this.’ So it’s not a loss in the long run.”

When the last day of twelfth grade arrived, Jamal Jones was still trying to figure out what he would do next. He was a quiet African-American boy with glasses who liked rock bands like Nirvana. He couldn’t get into rap because, as he saw it, it just didn’t make sense. He said people at another school had picked on him, but it didn’t happen as much at Kingsbury.

He said his friends were “overachiever people” and they’d sometimes make mean comments about his struggles. “It’s hard talking to them about it because they tend to put me down,” he told Patricia Henderson as he sat in her cubicle.

He told her he’d scored a 14 on the ACT, a low mark that was largely attributable to his problems in math. His father had died at age 22, his mother had dropped out of school when she got pregnant with him, and he stayed with his grandmother.

They talked some more, and Ms. Henderson suggested he go to Tennessee Technology Center or Southwest. Jamal had told me he liked music but saw majoring in that area as a risk. He’d taken a survey I’d passed out a couple of days before in the English classes—I’d asked a few basic questions on what the students planned to do after graduation. Jamal wrote that he’d go to Tennessee Tech. Asked about work plans, he wrote, “Simple manual labor or whatever my degree can get me.”

A total of 111 students answered my survey. The biggest group—41 percent—said they planned to go to technical school or community college. The second-largest group—36 percent—said they planned to go to the University of Memphis or another four-year college. Some of the students going to two-year or four-year colleges expressed interest in the military as well.

Six percent said they planned to forgo college and join the military immediately. Another six percent said they were considering both two-year and four-year options. I didn’t ask if the students had already applied and been accepted to college or to the military, so I can’t say if their intentions represented firm plans or vague dreams.

Ten percent of the students said they had no immediate plans to go to college or join the military.

One girl wrote that after graduation she would “have a long vacation.” Under college plans she wrote, “I don’t know.” Under work plans, “I don’t know.” A boy wrote: “I have no clue right now … Just work intill I find something I like to do.”

More than 100 seniors on the official roster didn’t answer the survey at all. Even if the sample wasn’t perfect, one theme came through clearly in the responses: many showed academic weakness. When I passed out the sheets, several students hadn’t brought pens or pencils to class, and I let them borrow mine. Many made basic errors in writing, like not putting periods at the ends of sentences. One misspelled “Tennessee,” the name of the state he lived in.

* * *

Some people believed that one way to avoid big academic weaknesses among high school seniors was to intervene years earlier, when they were small children. The younger the student at the time of intervention, the bigger the long-term impact, argued James J. Heckman, a Nobel Prize–winning economist.

Big gaps in skills open up very early between advantaged and disadvantaged groups in the United States, Heckman said. He argued that good preschools can raise both academic performance and “soft skills” like perseverance, attention, self-confidence and motivation, thus leading to long-term improvements in schooling, crime rates, workforce productivity and reduction of teenage pregnancy.

“Skill begets skill; motivation begets motivation,” he wrote in a presentation.10 “If a child is not motivated and stimulated to learn and engage early on in life, the more likely it is that when the child becomes an adult, it will fail in social and economic life.”

“The longer society waits to intervene in the life cycle of a disadvantaged child, the more costly it is to remediate disadvantage.”

Spending money on Pell Grants to help low-income kids afford college is less effective than early childhood training that sets them up to succeed in life, he argued.

Advocates for Hispanic children also pointed to preschool education as a priority. “If I had a magic wand, I would make sure that every Hispanic student had access to a high-quality early learning program in their community,” Alejandra Ceja from the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics told me. Deborah Santiago with the group Excelencia in Education likewise called for increased spending on early childhood education.

Hispanic children were the least likely of all major ethnic groups to attend preschool. Only 52 percent of Hispanic children aged three to six went to an early childhood program in 2012, compared to 63 percent of non-Hispanic white children and 68 percent of black children. Hispanic children were also the least likely to have the skills needed for kindergarten—for instance, recognizing all the letters of the alphabet and writing their first name. That said, they generally showed good skills in areas such as self-control and solving problems without fighting. And the proportion of Hispanic children in early childhood programs was trending upward.11

* * *

In the audio recording class on his last day of school, Isaias took a final exam in the studio, a wood-paneled space. As the other students continued to work on the test, he turned in his exam to teacher Corey A. Davis, who began grading it immediately and promptly told him he’d scored a 97. “Good job, Isaias. Very good.”

All too soon, the class was over, and Mr. Davis handed his business card to Isaias, pointing out his cell phone number and e-mail address on the back. “Call if you need anything.” He told Isaias to feel free to come back any time.

When that afternoon’s announcements started inside the main high school building, students began to shout. Mohammad Toutio leaped to a shelflike space on top of the lockers and sat there for a moment; someone else threw a handful of torn-up scraps of paper in the air, and they drifted down like confetti. Isaias said he’d tried to leave a reminder of himself at Kingsbury. “I wrote in my locker. Kind of just my name and date.”

* * *

Classes continued for students in grades nine, ten and eleven, and the next week, Rigo came back to school for his make-or-break exam for Mr. Tuminaro’s twelfth-grade English class. I spoke with him shortly before he took it. “I studied maybe 30 minutes a day,” he said. “Maybe. Since I left to Florida.” He laughed and looked away. “I procrastinated a little bit.”

That afternoon, Rigo went to Mr. Tuminaro’s classroom on the second floor for the test. The teacher sat at his own desk at the back of the room. Rigo took a seat at another desk turned around to face him. Mr. Tuminaro asked questions about grammar, then about the themes in literature they’d read, such as Lord of the Flies and 1984, then research methods. Each time Rigo answered a question, Mr. Tuminaro made a tally mark on a sheet of scrap paper.

Soon, the tally of wrong answers grew past the mathematical point of no return. Rigo had failed.

They sat silently for a moment. Mr. Tuminaro felt sad. He’d reached the same situation with a lot of kids. Sometimes they’d rush out crying or say “I hate you!” But Rigo took it well. They talked about summer school.

The conversation left Mr. Tuminaro feeling better. “As long as he can get to summer school, he’s going to be fine. He’s very, very talented. Very smart.”

* * *

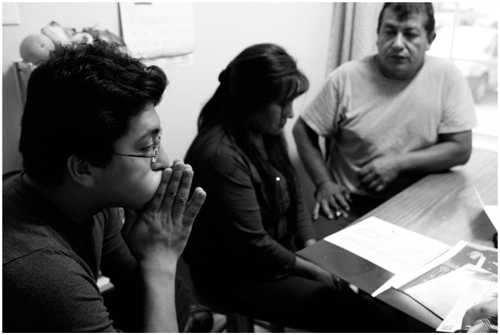

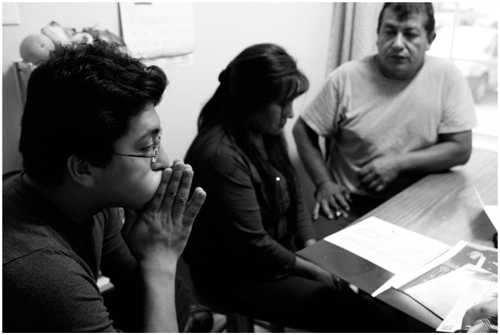

May 15 arrived, and Isaias waited in his bedroom for Margot and the other visitors who would try to change his path.

Outside, Dennis was using a bright orange cloth to polish his pickup truck when he saw Margot Aleman’s old Toyota Corolla turn into the quiet street, and he motioned for her to pull into the driveway. “You can park here!” Margot climbed out, along with Jennifer Alejo, the counselor from Latino Memphis, as well as Jacklyn Martin, the English teacher and Knowledge Bowl coach.

Dennis brought them through the front door and to the living room, where his parents waited. There was a flurry of introductions and greetings.

Isaias emerged from a back room, seemingly in a good mood. “Hi, Margot!” More introductions—though Ms. Alejo had worked in the school for several months, Isaias had never met her.

“You guys want to come into the kitchen?” he asked. He fetched a piano bench from the keyboard in his room. Isaias and his parents and the visitors took spots around the table, under the plaque of Jesus that Cristina had carried across the Arizona desert in her backpack.

Dennis stayed out of the kitchen.

Though the introductions had been friendly, everyone seemed a bit on edge. The visitors would use soft words, but they could not hide the blunt message that they questioned Isaias’ decisions, and no one could predict how he would take it.12 And they might even find themselves in direct conflict with his parents. Because Isaias’ parents understood very little English, Margot would have to interpret for the other two women.

“We love this boy a lot,” Margot began in Spanish. Mario replied, “We do, too!” Everyone laughed, and Margot realized that what she’d just said might suggest the visitors loved Isaias more than his own parents did. “No one’s going to win,” she said quickly. “If anyone loves him, it’s you.” Switching between languages, she continued. “We believe in him. He’s a very, very, very intelligent boy.” She pulled out a copy of his transcript. Isaias was surprised she’d brought it. “Really?” he said. She showed his parents his grade point average of 3.6 unweighted, 4.3 when the average was weighted to give extra points for harder classes. And she explained that he’d scored very well on an important exam, the ACT, a 29. “Eso es ridículamente alto,” she said—an awkward rendering of an English phrase: That’s ridiculously high.

Isaias maintained a serious expression.

Ms. Martin spoke up next, addressing Isaias’ parents, whom she’d never met before this night. “First of all, I just want to say that I have complete respect for Isaias and for you as well,” she began, and waited for Margot to interpret. “My purpose is not to make anyone decide anything or persuade. It’s simply to discuss some options.”

She had wanted to meet Isaias’ parents for a long time and tell them how special he was, but it had never happened, and she felt intimidated because she didn’t speak Spanish. Now the meeting was happening in their home, at a crucial moment in Isaias’ life, with all eyes on him.

Ms. Martin told Mario and Cristina that she’d never met another student who wrote as well as Isaias, not even students she taught at the university. She said Isaias once wrote a paper so good that another teacher thought he must have plagiarized it.

She paused again as Margot interpreted. “I also think it’s important to say I don’t believe that everyone should go to college. My brother, for example, never did well in school and didn’t like school, and so I don’t think college was for him.” Another pause. “However, I think that Isaias has so much potential that I strongly believe he would excel in college.

“And not just for a job or because it’s the right thing to do or to get a degree, but because I think that you would be able to expand and learn and meet so many neat people.” Isaias nodded.

Cristina sat with eyes down, uncharacteristically quiet, looking serious. Now it was Jennifer Alejo’s turn. She mentioned Victory University, the for-profit Christian school not far away. She said Isaias could study at night and work during the day with his family.

They brought out a folder of Victory recruiting materials, and Margot pointed to a photo of a young woman, a current Victory student on a scholarship. “I don’t know if you ever met her.”

“Oh, Bianca, yeah,” Isaias said. “I never met her personally, but I know her.” Bianca Tudon had graduated from Kingsbury in 2009, the same year as Dennis. She’d finished second in her class, and the principal still had her vivid painting of blues musician B. B. King hanging in his office. She had also been brought illegally from Mexico as a young child and couldn’t get in-state tuition at public universities. After high school, she went to work cleaning houses with her mother, earning about $30 per day, then went to work as a secretary in a law firm. Bianca’s father heard a recruiter talk about Victory on Spanish-language radio and encouraged her to apply. She’d enrolled the previous year.

Margot said that even at this late date, Isaias had such strong test scores that he could win scholarship money at Victory.

“All he has to do is apply. And this is thousands and thousands and thousands and thousands of dollars. This university is here, about ten minutes from here,” Margot said. She showed them the list of majors the school offered, including business administration.

Cristina spoke softly to Isaias. “Esto está muy bueno.” This is very good.

“Mm-hmm,” Isaias murmured.

A few moments later, Mario finally spoke up. “In fact, I’ve been excited for a long time about having a son in the university,” he said in his soft, gentle voice. “We’re from a family of campesinos, humble, and we didn’t have great opportunities. We had to work like donkeys.”

Mario said Isaias had told him a few weeks earlier that he’d decided not to attend college: “It hit me like a splash of water.” He said they’d come home and talked about it as a family. “I told him that I’d made many mistakes in my life and I’m not going to make a mistake with you. You’re going to decide.” He would support Isaias either way.

Ms. Martin said she felt exactly the same. “I would be proud of you, Isaias, no matter what you did. Honestly, I’m just proud to know you.” Ms. Alejo said Isaias should act fast, though, since his high school scores would go stale after a few years.

Cristina turned to Isaias. “¿Tú que piensas?” What do you think?

“Estoy escuchando.” I’m listening.

A clock ticked in the background. They talked some more. Ms. Martin asked Isaias if he felt pressured, and he indicated he didn’t.

“Okay, good. I really want you to know this is not about pressuring you. I even joked like this is a college intervention. It’s not like that. It’s just that we want you to know that you have options, and we want to make sure that you look at your options before you make a decision. That’s all.”

Margot spoke up again. “I want to ask him a question. Y la pregunta es, ¿cuál es tu razón por no ir al colegio?”

Isaias responded, “Okay, well, the question you asked is like ‘Why don’t I want to go to college.’ I’ve already told this to my parents so I guess I can say it in English.”

(Photo by Karen Pulfer Focht/The Commercial Appeal)

“Like … the reason—I guess it’s a big, complicated reason,” he said. “But, like, most importantly, I ask myself, ‘Why am I going? What am I going to do there? Is it the place for me?’”

He said he had two choices right now. He could work, save money, start buying houses and renting them out. “Invest in the stock market, why not?” Or he could spend years studying and start again at the bottom of a company. And did he truly want to become a conformist wage slave?

“People who say that money is no matter to them, that they don’t care about money, but they still get up in the morning to pay their bills, like they look forward to their paycheck so they can buy a Snickers bar or go somewhere, or go downtown … Like, do I want to be part of that? I really don’t.”

One by one, everyone around the table made a case for college. Margot said a business degree could open doors. Ms. Alejo said a degree could lead to personal connections. Ms. Martin offered a different perspective. “I think you raised a lot of valid points, kind of like being a slave to your hourly day. I mean, I get that. But to be fair, if you were renting houses, like a lot of your argument for not going to college was financial. You know. Renting houses, and then I can rent another house to get a paycheck. You know, like, it’s similar.”

“It’s similar,” Isaias agreed.

She said he was missing something important. “I told you this before. I didn’t go to college to get a job or to get money. I went to college because I liked learning. And I loved it. I loved it so much that I might even go back and get a Ph.D. because I read so much and I was exposed to philosophy and different languages and I got the first person ever who beat me at chess. And those experiences you can’t always trade in.”

Isaias’ father fiddled quietly with a carpenter’s pencil, a flat, blue thing. Margot turned to Cristina. “¿Cómo se siente usted, señora?” How do you feel, señora?

Cristina responded, “I felt awful when he told me ‘I don’t want to go to school anymore’ after he’d told me so many times that he was going to go.”

She breathed out softly, then turned to Isaias again, and said he shouldn’t think education would stand in the way of his dreams. “It could help you and make things easier. We ignorant people don’t know anything, and you do.”

His father weighed in, too. “At first we were afraid we wouldn’t be able to cover the costs. How am I going to pay? Even so, I told him that if you decide, we’ll have to do it.” He said he’d seen Isaias stay up all night doing homework and knew his capacity. “I know he can do it, and everything’s in him. Right now, if it were up to me, I would grab him by the ears and throw him in the university.”

Margot said she’d spoken with Adriana Garza, the recruiter at Victory. If Isaias wanted to win a scholarship, he would have to apply immediately. Margot told Isaias’ parents she’d go with them if they wanted to speak with Ms. Garza the next day.

Mario said, “Right now let us talk with Isaias, see what he thinks and we’ll call you immediately.” From another room, the low sound of Dennis playing bass drifted into the kitchen. For Isaias’ father, the visit from the teachers marked a rare moment in America in which someone had reached out and tried to help them. “Thank you for coming and thank you for worrying about him,” Mario said. “I’ve been worried about him, too.”

Then the visitors left.

Afterward, Jacklyn Martin felt worried. She knew that Isaias rejected the concept of God just as he rejected college. How would an atheist fit in at a Christian school like Victory? And how would this sometimes rebellious 18-year-old respond to the pressure of the intervention? Isaias had stayed silent for so much of the visit. She texted me.

He’s not going to go, is he?