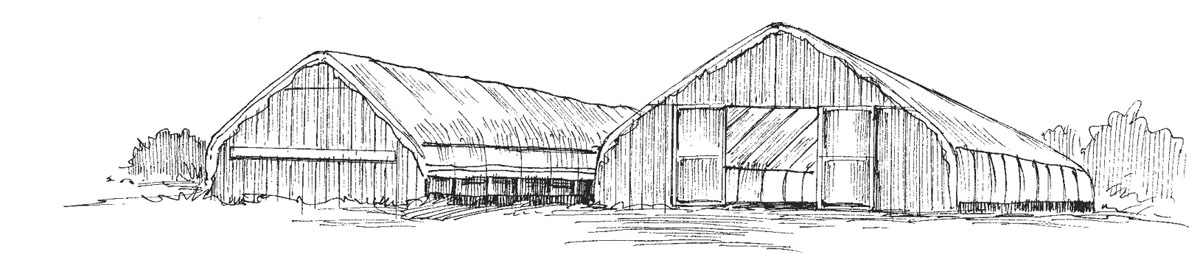

High tunnels are passive solar structures. Plants are grown directly in the ground without artificial heat. Note the end doors and roll-up sides, which are used for ventilation.

Let me start by saying what a high tunnel (or low tunnel, for that matter) is not. A high tunnel is not a greenhouse, though from a distance it may look like one and, in fact, may be made from the same materials. A greenhouse, at least as we have defined it in chapter 6, is a place to start plants from seed — usually in flats or pots that rest on benches. A standard greenhouse will have a heater for when the temperature inside drops too low and an exhaust fan for when it gets too high.

Your typical tunnel, however, whether it be high or low, has neither a heater nor an exhaust fan. It is a very low-tech, eco-friendly structure because it relies only on the sun for its warmth and on roll-up sides and open doors to keep it from getting too hot. Plants in a tunnel are usually grown in the ground, just as if they were in the field. In fact, you could say they are grown in the field — it’s just that they have a tunnel over the top of them.

We have two high tunnels on our farm. The smaller one is 21 by 96 feet and 11 feet high. The larger is 30 by 96 feet and is 14 feet high. I see more high tunnels in our future.

High tunnels are passive solar structures. Plants are grown directly in the ground without artificial heat. Note the end doors and roll-up sides, which are used for ventilation.

High tunnels have become increasingly popular with organic vegetable growers for several very good reasons. The one most often cited is season extension in both spring and fall and, in some cases, even into the winter. Other noteworthy benefits include: Protection from the elements and most herbivores; better-looking, higher-yielding, and better-storing crops; and a good place to work when it’s cold or wet outside. Here, we’ll consider these and a few other good reasons to invest in one or more high tunnels. For many growers, it’s an investment that will soon pay off.

Most farmers in North America are constrained by the length of the growing season, which is usually defined as the number of frost-free days. Tender field-grown crops, such as tomatoes, cucumbers, and basil, cannot be planted until after the last frost of spring and end their lives when the first frost arrives in fall. Hardier plants such as lettuces, kale, and spinach can survive and even prosper in the field much longer at both ends of the season, but eventually, their days of reckoning come.

A high tunnel can extend the season for any of these crops by a few weeks or even a month or more in both spring and fall. You can provide additional protection by creating a low tunnel within a high tunnel — hoops and a blanket or two of row cover will keep many cold-hardy plants alive through most or all of winter. It should be noted, however, that during the coldest and darkest months, plant growth will slow almost to a halt. Whether you opt for the protection offered by a high tunnel alone, or use the “tunnel-within-a-tunnel” approach, you will extend your harvest season and increase yield.

Wet outdoor conditions often delay spring planting, even though temperatures may be high enough. You can’t plow or rototill a field while it is still saturated with water. But even in the wettest spring, the soil inside a high tunnel will be relatively dry, except perhaps for some seepage along the edges. This means you can plant as soon as you feel the days and nights are warm enough for your crop. Regardless of the time of year, you seldom have to worry about the ground being too wet under a high tunnel.

As is well known, and often stated in this book, many of the problems that beset field-grown plants are caused by the weather. Excessive wind, hail, and rain can damage and stress plants. Wind desiccates many vegetables and slows their growth; hail can destroy plants, or at least cause injuries that make them more vulnerable to invading insects and diseases.

And rain, because it is so common, is the biggest worry of all — wet foliage makes it easier for diseases that might be lurking in the neighborhood to gain a foothold and spread. Foliar diseases, in particular, are a real problem for organic growers who don’t have chemical fungicides in their tool chests.

Inside a high tunnel, plants are largely protected from these three forces of nature.

Crops grown under high tunnels are often better looking, better tasting, better storing, and higher yielding. Field crops that bear fruit, such as tomatoes and peppers, do fine when the weather cooperates. But if they receive prolonged, heavy rain or an unexpected spell of cold weather, their growth slows down, and their quality and appearance can take a quick turn for the worse. With tomatoes, especially, splits and cracks are common when the plants absorb too much water within a short period of time. A promising crop can soon turn into a harvest of “seconds” with a short shelf life and disappointing flavor.

Heavy rain causes soil to splash up on lettuces, escarole, and many bunching greens, making them less attractive, unless you go through the laborious process of washing individual heads and bunches. Saturated greens, as just about every other vegetable, don’t taste as good or last as long. This is not to suggest that cool weather greens are a good choice for a high tunnel during summer months. They are not. But in early spring and late fall, they can do very nicely indeed.

An earlier planting date, more warmth when needed, and protection from the sometimes destructive forces of nature will combine to produce significantly higher yields in high tunnels.

A couple of years ago, we found a nest of baby rabbits in one of our tunnels. We evicted them as soon as they were big enough to hop off on their own. That’s about the only time I’ve seen four-legged herbivores inside a tunnel. To date, no deer or woodchucks have ventured in, so we haven’t had to worry about fences or other deterrents, which is certainly not the case with our field-grown crops. Sometimes, birds fly into the tunnels and dine on any insects that have taken up residence, but this we don’t mind.

In July 2009, after a long spell of cool, wet weather, we got late blight in our field tomatoes and lost the entire crop (more than 2,300 plants) in a couple of weeks. Of course, we didn’t just lose the plants. We also lost a considerable amount of labor and resources. Beds in three different fields had been carefully prepared, black plastic and drip tape laid, each transplant set in the ground by hand, and each given spoonfuls of rock phosphate and organic fertilizer. Some eight hundred wooden stakes and a few days of vigorous work had gone into trellising the young plants using the Florida weave (basket weave) system. All of this time and resources amounted to nothing.

That year, we had also put some 50 tomato plants in our one high tunnel, figuring they would give us a modest amount of ripe fruit before the field tomatoes came in. This they did, but more importantly, they continued to grow and produce fruit for a couple of months after the scourge of late blight hit us.

Our tunnel tomatoes did eventually contract late blight, but because their foliage stayed dry, the disease was not able to spread as rapidly as it did in the field. We harvested at least 500 pounds of fruit before the plants finally succumbed. Not a bountiful haul, I’ll admit, but enough to bring in a couple of thousand dollars and convince me to invest in a second tunnel. This second, larger tunnel now houses about three hundred tomato plants, along with lesser numbers of peppers and herbs. It has nearly paid for itself in 2 years.

Tunnels cost a lot less to build and maintain than greenhouses, largely because they require only one sheet of poly and don’t need a heater, fuel, fan, louvers, or the wiring and electricity that greenhouses call for. Most growers, with a good set of instructions and a couple of willing helpers, should be able to construct a high tunnel without professional assistance. The cost and the amount of setup time will vary depending on the size of the tunnel.

Cost estimates range from 75 cents to $1.50 per square foot for the basic hardware and plastic needed; therefore, a 21- by 96-foot tunnel would run you somewhere between $1,500 and $3,000. The heavier the gauge of steel, the higher the price. Then, you will need lumber for baseboards and to frame out endwalls and possibly doors. It may also be necessary to do some site preparation, such as leveling with a bulldozer.

There is also the matter of bringing water to the tunnel. If you’re not planning to grow plants in subzero temperatures, garden hoses and shutoff valves might be adequate. Most growers, though, will want the option of irrigating their tunnel during the winter months. A buried water line and frost-free hydrant will make cold-weather irrigation a lot easier but will add to the price tag. When all is said and done, your final cost could go up by 20 to 40 percent; therefore, you might end up spending $4,000 or more for a 21- by 96-foot tunnel. Not exactly small change, but still a good investment. Many farmers find that the larger and more reliable yields they gain from a high tunnel cover the cost of their investment in 3 or 4 years.

We bought our two tunnels from Ledgewood Farm in New Hampshire. Ed Person, the proprietor of Ledgewood, was very patient with us and offered plenty of guidance and advice. The tunnels are sturdy and can handle severe winter conditions. Other high-tunnel merchants include FarmTek (Iowa), Agra Tech (California), A.M. Leonard (California), Poly-Tex (Minnesota), Zimmerman (Missouri), and Harnois (Quebec). The English company Haygrove offers a wide selection of single-bay and multibay tunnels at very competitive prices.

If you’re on a very low budget, you might look into building your own smaller and less sturdy tunnel with rebar ground posts and 1.5- to 2-inch schedule 40 PVC.

Like greenhouses, high tunnels provide a nice change of work venue — except in the middle of a very hot day. The environment inside a tunnel, even when the sides are rolled up, is quieter, less windy, and often more soothing and contemplative than the rough-and-tumble of the open field. On cold days, when temperatures are below freezing, it can be quite pleasant inside a tunnel as long as there is some sun in the sky. Even in overcast weather, it will be noticeably warmer inside a high tunnel.

Before we had high tunnels, it was always a challenge to find productive work for the crew and me on seriously rainy days. Now when I make up a work plan for the week ahead, I schedule tunnel chores — such as pruning, trellising, harvesting, or weeding — for any wet days. This way, all of us stay dry, and the fields are spared the compacting effects of human traffic on wet soil. On cold days, too, the tunnels are always the preferred spots to be.

The tunnels are especially important on rainy harvest days. Really bad weather can seriously interrupt picking in the field. This is never a problem in a tunnel.

Many farmers have found that high tunnels not only extend the season for certain crops and therefore expand their income-producing window, but they also make it possible to retain employees who otherwise would have to be let go when the season winds down. When you can offer only 6 or 8 months of employment, there’s a good chance you won’t see that season’s workers ever again. Holding onto productive employees for an extra couple of months and possibly the entire year is very appealing to many farmers.

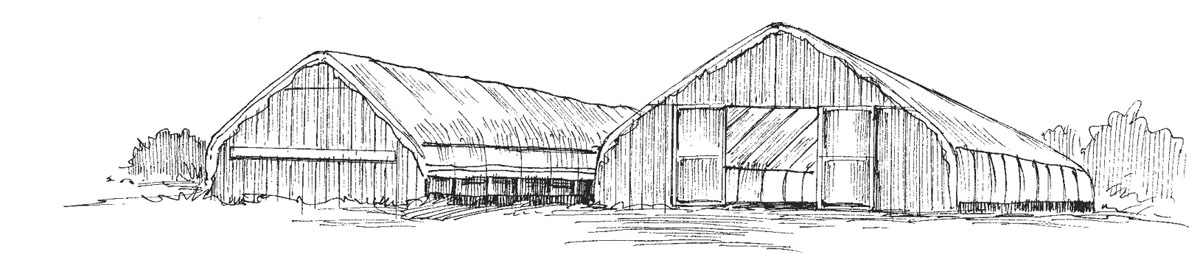

Because tunnels require a significant investment of capital and labor, most growers want to get as much production out of them as possible. One way they do this is by exploiting the vertical dimension. With tomatoes, for example, farmers often use a trellising system that allows the plants to grow to a height of 8 feet or more on a single stem, producing fruit all the way to the top. The fruit stays clean and is easy to pick. This use of vertical space would be very difficult to achieve in the open field. For more details on growing and trellising tomatoes in a high tunnel, see chapter 13.

Some growers exploit the vertical space in their tunnels by suspending hanging plant baskets above low-growing crops such as peppers or cucumbers.

The trellised tomatoes growing in this high tunnel are pruned to a single stem.

Before you set out to construct your first high tunnel, you need to choose a good site for it. Orientation with respect to the sun and ventilation through prevailing winds are important factors to consider. Other variables that will come into play, but are not necessarily site specific, are provisions for pollination of fruit-bearing crops and the methods you will use to maintain fertility. You also want to consider your long-range plan for crop rotation.

The site. Like greenhouses, tunnels are best located on level ground away from any objects that might throw shade. A slight slope is okay if it is along the length of the tunnel. Avoid any slope from one side to the other.

Orientation. Because air movement is so important, many growers choose to orient their tunnels perpendicular to the prevailing winds so that during the hot months, they can capture as much free air as possible through the roll-up sides. If, on the other hand, you’re trying to maximize the amount of sunlight reaching your tunnel during the winter months, you might choose a different orientation.

For maximum sunlight, the rule of thumb is this: In the Northern Hemisphere, above 40° latitude, the best orientation is east–west (it captures more low-angle sun). Below 40° latitude, a north-to-south orientation is better (the sun is much higher in the sky at these latitudes). For a more detailed discussion of orientation, see the website Hightunnels.org.

Ventilation. Tunnels with widths of 21 feet are usually ventilated well enough by natural airflow. Wider tunnels (30 feet is generally the widest for single-bay tunnels) can have ventilation problems, especially in their centers. Some growers install overhead fans in wide tunnels to keep plants in the middle rows drier. See page 333 for more on ventilating high-tunnel tomatoes.

Pollination. In the absence of insects, many crops, such as tomatoes, rely on the wind for pollination. So if you want plenty of fruits to develop, and are short on insects, you need to have a good flow of air through your tunnels after flowers have set. You might also try physically shaking the plants to help them self-pollinate.

Fertility. Because you want your high-tunnel plants to produce as much as possible, you need to maintain a high level of fertility in the soil in which they are growing. This usually means adding ample amounts of compost and possibly other amendments after each crop. Fallow periods and green manures, especially leguminous ones, are good for building soil health and fertility, but they temporarily remove valuable real estate from production. For this reason many growers don’t use these soil-building measures as often in their tunnels as they do in the open field.

Crop rotation. Rotating crops in high tunnels can be a major challenge because of the limited number of crops. In the absence of a good rotation plan, it is helpful to maintain high fertility and use disease-resistant varieties. Tomato growers may use grafted plants to reduce the chance of disease.

Of course, the more tunnels you have, the more you will be able to rotate different crops through them. You could also use smaller tunnels that can be easily dismantled and periodically moved to different locations. Some tunnels are actually designed to be moved on sleds, with the aid of a couple of tractors.

In addition to its roll-up sides, this high tunnel has an overhead fan to distribute air around the plants in the center.

Low tunnels and caterpillars offer many of the same advantages that high tunnels provide, but not all. They are generally temporary structures used for season extension and protection from pests, diseases, and the elements.

The big difference between a high and a low tunnel is that you can stand up in one but not in the other. Another difference is cost — low tunnels cost a lot less. Once you have the hoops and the covering, you can put up low tunnels very easily. They are usually 2 to 3 feet high and 4 to 5 feet wide; length varies depending on need. Simple low tunnels are often used to keep insects away from vulnerable crops in summer. In the colder months, they are used for season extension and sometimes even overwintering.

Low-tunnel hoops can be made from 10-foot lengths of galvanized electrical conduit that is 1⁄2-inch-diameter, 1-inch PVC pipe and rebar posts, or 10-gauge galvanized wire. The conduit-style hoops are the strongest and most able to withstand a substantial snow load in winter. An inexpensive hoop bender will let you make your own uniform hoops. Wire and PVC hoops are less sturdy but will do a good job of protecting crops in spring, summer, and fall.

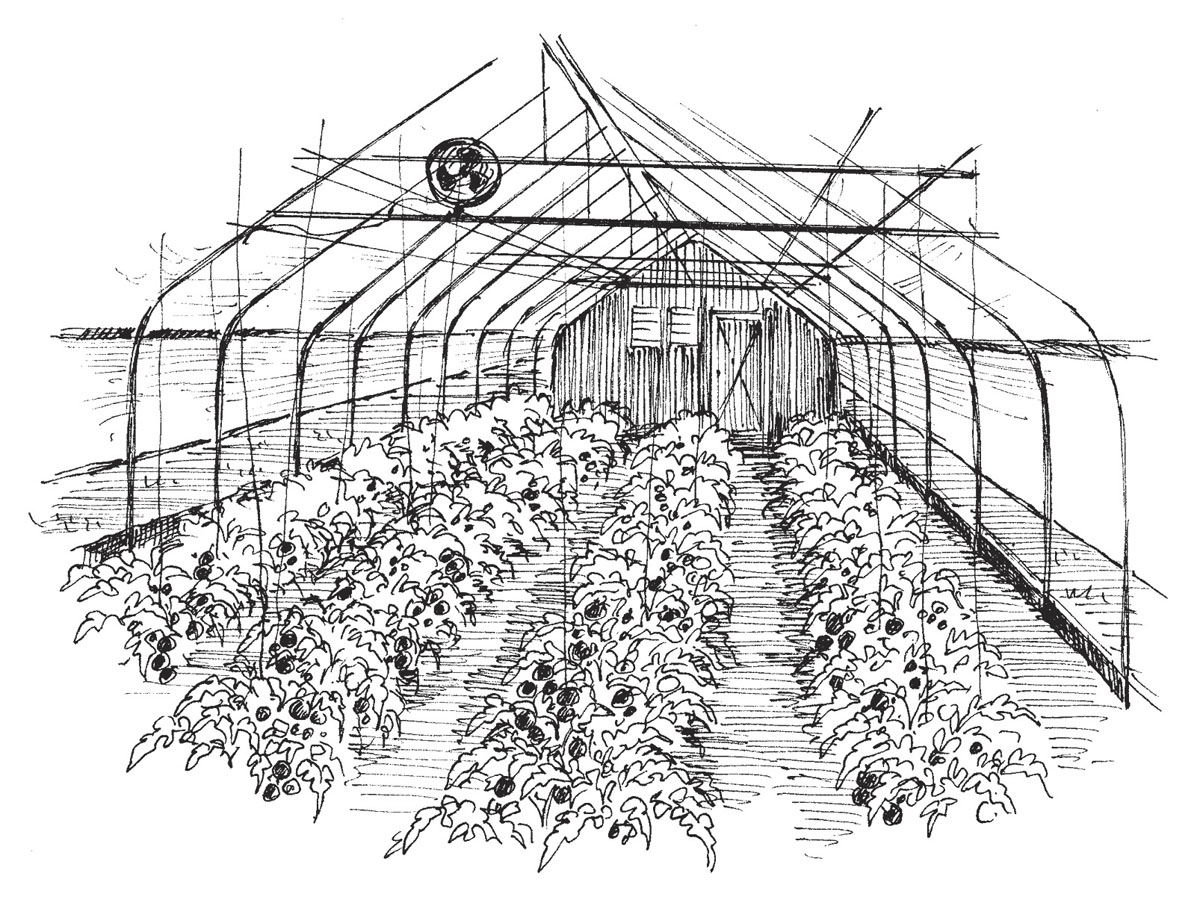

The row cover on these low tunnels is draped over hoops made from 1⁄2-inch galvanized electrical conduit.

Regardless of the material used, hoops are placed 4 to 5 feet apart and set well into the ground on either side of the bed you are planning to protect.

To protect crops from insects, drape lightweight row cover or gauze over the hoops and weigh it down with sandbags, bags of gravel, or any other heavy objects that you have on hand. Shoveled soil can also be used to hold down row cover but is impractical if the row cover is going to be repeatedly removed and replaced, as is often the case when harvesting. Row cover buried under soil also degrades more rapidly. For season extension, use heavier weights of row cover with greater insulating value.

Growers wishing to protect crops through winter often drape a layer of greenhouse poly over the row cover. This can work quite well but only when the hoop structure is sturdy and sufficiently braced to withstand the vicissitudes of winter. Use cross ropes to hold the plastic in place, along with sandbags or other heavy weights. Stakes at either end of the tunnel will keep both plastic and row cover taut and prevent them from caving in under a heavy snow load.

Different designs for low tunnels can be readily found online. Check out Eliot Coleman’s “double-covered low tunnels.” You can read about them in an online article by Jean English titled, “Extending the Growing Season with Coleman’s Double-Covered Low Tunnels.” Or get a copy of Coleman’s Winter Harvest Handbook or his Four-Season Harvest. Eliot is a pioneer of season extension in the United States.

There’s much more to learn about high tunnels than what I’ve covered in this chapter, and a great place to start learning is the website Hightunnels.org. This site is maintained by an assortment of Midwestern Extension specialists, college professors, researchers, growers, and students, all with a strong interest in sharing their knowledge and experience of high tunnels.

The Hoophouse Handbook (see Resources) is an excellent collection of essays covering high-tunnel design, construction, and uses. The essays are written by growers with firsthand experience.

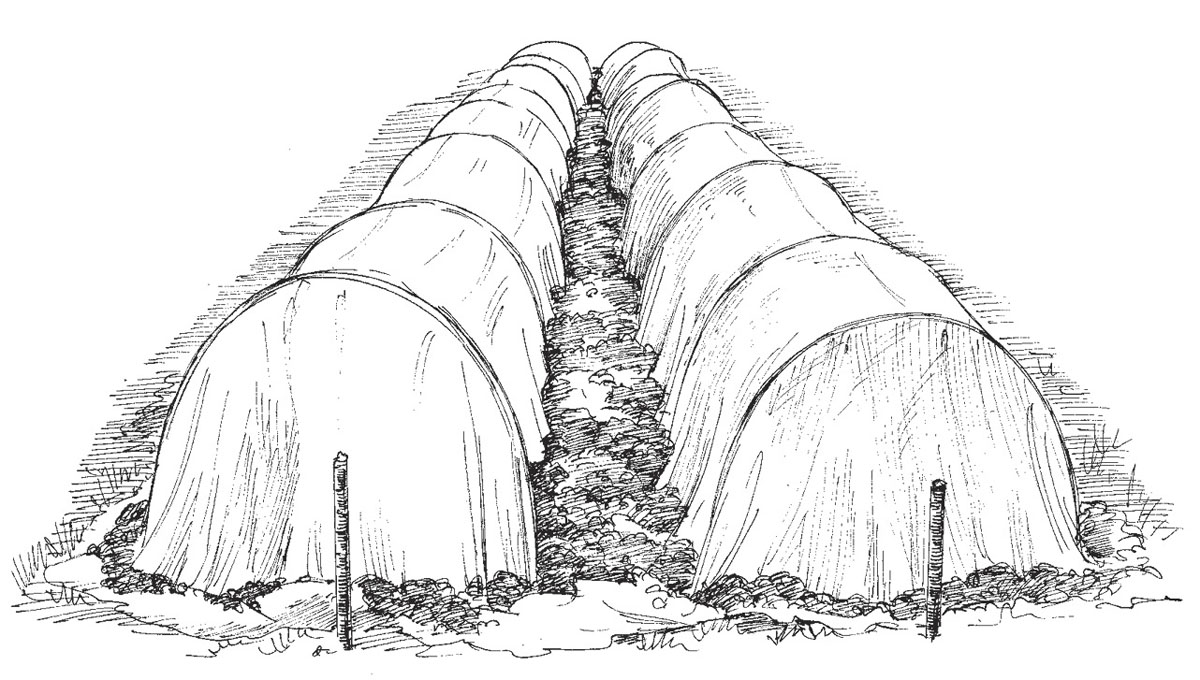

A caterpillar tunnel is a low tunnel on the way to becoming a high tunnel. The typical caterpillar is 51⁄2 to 6 feet high, about 10 feet wide, and any length up to 300 feet. A person of average height should be able to walk down the center, as long as he or she avoids a bouncing gait. Inside a tunnel of this size, there should be enough room for two 4-foot-wide beds.

Caterpillars are easy-to-erect temporary structures that don’t require perfectly level ground. They can be built with some of the same materials one might use to build a sturdy low tunnel; namely, rebar posts driven into the ground and 1-inch-diameter PVC hoops fitted over the top of them. Or, you might purchase 10-inch-wide hoops from a greenhouse vendor. As with the Eliot Coleman–style “double-covered low tunnel” mentioned above, a rope is often wrapped around the top of each hoop along the length of the tunnel, then tied to stakes firmly set into the ground several feet beyond either end of the structure. This added reinforcement gives better protection against wind and snow.

This caterpillar tunnel frame is made with 10-inch-wide hoops.

Caterpillar tunnels may be covered with row cover or greenhouse poly, depending on the time of year and the inside temperature desired. Cross ropes, in addition to sand bags or other weights, should be used to hold the row cover or greenhouse poly in place and prevent billowing.

Caterpillars may be used to extend the growing season well into winter, or to provide heat-loving plants with a warmer environment during spring and early summer. When temperatures rise, however, caterpillars that are covered with greenhouse poly will need to be ventilated by rolling back the poly or opening the ends, or both.

Winters in Dane County, Wisconsin, are severe. Nighttime temperatures of −15°F (–26°C) are not uncommon, and they can drop even lower. Well before it gets this cold, most growers take a break and put in some time with the seed catalogs. But not Bill Warner and Judy Hageman of Snug Haven Farm. They see the cold weather as a marketing opportunity. Bill and Judy’s specialty is spinach. They say it tastes sweeter and crunchier when it has gone through a few good freezes.

Apparently, their customers agree: Bill and Judy sell a lot of spinach. Their outlets include the Dane County Farmers’ Market in Madison (the largest producer-only farmers’ market in North America); their own winter share program, which is like a mini-CSA (shareholders receive a 1-, 2-, or 3-pound bag of spinach every other week, for 11 weeks); and some of the finest restaurants in Madison and Chicago. Winter spinach grows more slowly than spinach planted for spring or fall harvest, but it is thicker and hardier, and by all accounts, it tastes better.

The bulk of the growing at Snug Haven Farm is done in high tunnels, or hoop houses, as Bill calls them. The farm has a total of 13 of these season-extension structures. They cover about 1 acre of land and range in size from 30 by 96 feet to 32 by 145 feet. All the spinach is planted in September. Harvest takes place weekly, from late October or early November until late April, but never before the plants have experienced freezing temperatures.

When it drops well below freezing outside, the spinach gets an extra blanket, in the form of a second layer of greenhouse polyethylene, to keep it warm at night and on seriously cold, overcast days. This layer is draped over what Bill Warner calls a substructure made from 0.5- and 3⁄4-inch electrical conduit. The two sizes of conduit are cut and fit together to form 4-foot-high by 30-foot-wide support structures. The assembled pieces are spaced 6 to 8 feet apart. They reach across the entire width of a hoop house and are flat across the top, rather than bowed.

On warmer days, the sides and ends of the tunnels are opened to prevent the spinach from getting too hot and to allow excessive condensation to evaporate. Sometimes, Bill uses large sheets of row cover instead of polyethylene, though he prefers the poly for a few reasons: It seldom tears, it warms the spinach a little faster when the sun comes up, and it enables him to get a second use out of material that has already had a first life covering his hoop houses. But because the poly doesn’t breathe as well as row cover, it requires more careful management. Even under its double covering, the spinach freezes repeatedly, but the soil inside the hoop houses rarely freezes. When it does freeze, it freezes no more than 1⁄4 inch deep for a few hours in the morning.

Snug Haven Farm’s hoop houses are not heated in the conventional sense, but on cold days, they may be warmed up for an hour or two with propane furnaces, to create a more comfortable harvesting environment. It’s tough to cut spinach for any length of time when the temperature is much below 45°F (7°C). When necessary, the heaters are also used, for short periods, to thaw the spinach before harvesting.

Snug Haven Farm follows organic methods, but it is not certified. To Bill, the federal government’s involvement and all the paperwork are big disincentives. Still, he hasn’t altogether ruled out organic certification. The farm employs three or four part-time workers to help harvest the spinach, pick tomatoes in spring and summer, and do other chores. Each year, one of the hoop houses is converted into a greenhouse for starting tomatoes and flowers.

By early April, it’s getting a bit warm to grow the kind of spinach that Snug Haven Farm likes to grow. This is when Bill and Judy switch to hoop-house arugula, tomatoes, flowers, and, from time to time, a few other assorted vegetables and herbs. Their goal is to have their wares at the market before the flood of fresh field-grown produce arrives. It’s sometimes chilly work, but it pays off.