4

The Internet Will Be Decolonized

Kavita Philip

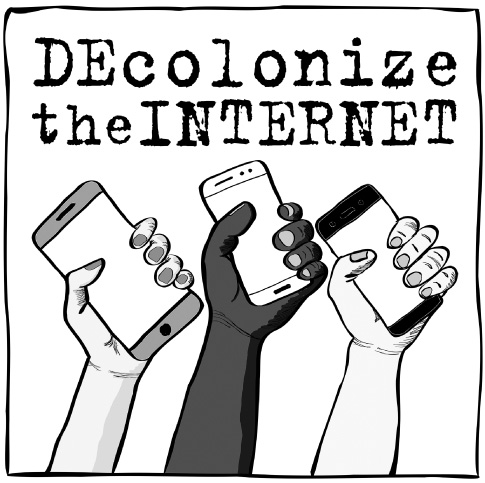

Policy makers and internet activists were gathering in South Africa to “decolonize the internet,” a 2018 news headline announced.1 How does the internet have anything to do with colonialism, and why do global campaigners seek to “decolonize” it (see fig. 4.1)?

Activist agitations against the “colonial” internet open up a Pandora’s box of questions that this chapter attempts to excavate. The slogan “decolonize the internet” belonged to a global campaign called “Whose Knowledge?,” founded in the realization of an imbalance between users and producers of online knowledge: “3/4 of the online population of the world today comes from the global South—from Asia, from Africa, from Latin America. And nearly half those online are women. Yet most public knowledge online has so far been written by white men from Europe and North America.”2 Whose Knowledge? and the Wikimedia Foundation came together to address a problem exemplified by the statistics of global internet use.

Whose Knowledge? is one of a profusion of social movements that seek to reframe the wired world through new combinations of social and technological analysis.3 Critiques of colonialism, in particular, have been trending in technological circles. All of the ways we speak of and work with the internet are shaped by historical legacies of colonial ways of knowing, and representing, the world. Even well-meaning attempts to bring “development” to the former colonial world by bridging the digital divide or collecting data on poor societies, for example, seem inadvertently to reprise colonial models of backwardness and “catch-up strategies” of modernization. Before we rush to know the Global South better through better connectivity or the accumulation of more precise, extensive data, we need to reflect on the questions that shape, and politicize, that data.4

Figure 4.1 Campaign graphic, Decolonize the Internet! by Tinaral for Whose Knowledge? Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

How might we use historical knowledge not to restigmatize poor countries but to reshape the ways in which we design research programs that affect the world’s poorest and least connected?5 Rather than offering new empirical data from the Global South, then, this chapter steps back in order to reflect on the infrastructures that help create facts about the world we can’t see, the part of the world we believe needs to be developed and connected. In order to redesign our ideas, perhaps we need a more useful lens through which to observe intertwined historical, social, and technical processes.

This chapter begins to construct such an analytical lens by surveying diverse social and technical narratives of the internet. The internet is literally the infrastructure that enables our knowledge and activities about the world, and if the internet is shaped by colonialism, we need to understand what that means for the knowledge we consider objective. Once studied only as a remnant of past centuries, colonialism and imperialism are now seen as structuring the ways in which internet-based technologies are built, maintained, and used. In order to understand why scholars, designers, and users of the internet are grappling with the historical legacies of colonialism, we must broaden our frame of analysis to ask why history matters in the stories we tell about the internet and the techniques by which we are “datafying” global development. We begin, then, by surveying different ways of thinking about the internet, drawing from popular discourse, technical maps, and media theory.

Information Is Power, But Must Technology Be Neutral?

“If information is power, whoever rules the world’s telecommunications system commands the world,” argues historical geographer Peter Hugill.6 He traces the ways in which the power of British colonial submarine cable networks was eclipsed by post–World War II American communications satellites. He observed in 1999: “Just as American radio communications challenged the British cable ‘monopoly’ in the 1920s, European satellites and fiber-optic lines and Asian satellites are now challenging American satellite and submarine telephone cable dominance.”7 Despite this historically global stage on which technology and power have played out, studies of the internet still tend to be nationally or disciplinarily segregated and often remain innocent of colonial histories. It is hard to integrate varied disciplinary and national perspectives, and even harder to know why they matter. Euro-American studies tend to take high-bandwidth infrastructural functioning for granted and focus on representational and policy issues framed by national politics. “Developing world” studies, then, focus on bridging the digital divide and the challenges to infrastructural provisioning.

There are many definitions of the internet, and that descriptive diversity reflects the many ways in which people experience the internet. The last few decades have offered up several competing narratives about the internet, none of which are strictly false. For example, activists draw attention to the ways in which representational inequities are reshaped or perpetuated by new communication technologies. Media studies scholars focus on how the technical affordances of the internet, such as speed and decentralization, shift forms of media representation and the reconstitution of audiences, publics, and producers. Materials science experts tell us that the internet is really the infrastructural backbone of cables under the sea and the satellites in the sky, and its everyday functions depend on the atomic-level properties of cable and switch materials. Network engineers talk about internet exchange points and the work it takes to make them operate seamlessly and securely. Social media researchers tell us that the internet is essentially made up of the platforms that frame users’ participation in dispersed communities. Internet service providers, managing the flow of information through digital “pipes,” describe business plans to sell consumers space for our data while lobbying against net neutrality protocols with government regulators. All of these stories are true; each emphasizes, from a particular professional perspective, an important aspect of the internet. Each embodies particular assumptions about individual, corporate, state, and transnational behaviors.

Rather than attempting to consolidate one static, comprehensive definition, let us try to understand how disparate stories about the internet enlisted particular audiences in the last decade of the twentieth century, and why it mattered when one internet narrative was favored over another. One persistent fault line in late-twentieth-century narratives about the internet derived from the geographic and economic location of the narrator. In the 1990s, tech visionaries in the West extolled the internet’s creative virtual worlds, while visionary discourse in the Global South more commonly celebrated the engineering feats of big infrastructure projects. This may have been because infrastructure tended to recede into the background when it worked well and was dramatically foregrounded when it failed.8 First Worlders in the mid- to late twentieth century tended to take roads, bridges, wires, and computer hardware for granted, while Third Worlders experiencing the financially strapped “development decades” were painfully aware of the poorly maintained, underfunded infrastructures of communication technology. As the new millennium began, however, the growth of emerging markets reversed some of this polarity. Globally circulating scholars began to challenge this conceptual divide in the first decades of the twenty-first century (as Paul N. Edwards’s chapter in this volume documents).

But a curious narrative lag persistently haunted digital maps and models. Even as the global technological landscape grew increasingly dominated by emerging economies, popular internet stories shaped the future’s imaginative frontier by reviving specters of backwardness. Cold War geopolitics and colonial metaphors of primitivism and progress freighted new communication technologies with older racialized and gendered baggage.

Mapping the Internet

Internet cartographers in the 1990s devised creative ways to represent the internet. A 1995 case study from AT&T’s Bell Laboratories began with a network definition: “At its most basic level the Internet or any network consists of nodes and links.”9 The authors, Cox and Eick, reported that the main challenge in “the explosive growth” in internet communications data was the difficulty of finding models to represent large data sets. Searching for techniques to reduce clutter, offer “intuitive models” of time and navigation, and “retain geographic context,” the authors reported on the latest method of using “a natural 3D metaphor” by drawing arcs between nodes positioned on a globe. The clearest way to draw glyphs and arcs, they guessed, was to favor displays that “reduce visual complexity” and produce “pleasing” and familiar images “like international airline routes.”

The spatial representation of the internet has been crucial to the varied conceptualizations of “cyberspace” (as a place to explore, as a cultural site, and as a marketplace, for example).10 The earliest internet maps were technically innovative, visually arresting, and rarely scrutinized by humanities scholars. New-media critic Terry Harpold was one of the first to synthesize historical, geographical, and technical analyses of these maps. In an award-winning 1999 article, he reviewed the images created by internet cartographers in the 1990s, observing that, in Eick and his collaborator’s maps, “the lines of Internet traffic look more like beacons in the night than, say, undersea cables, satellite relays, or fiber-optic cables.” Harpold argued that although genuinely innovative in their techniques of handling large data sets, these late-twentieth-century internet maps drew “on visual discourses of identity and negated identity that echo those of the European maps of colonized and colonizable space of nearly a century ago.” Early maps of the internet assumed uniform national connectivity, even though in reality connectivity varied widely from coast to hinterland or clustered around internet cable landing points and major cities. These maps produced images of the world that colored in Africa as a dark continent and showed Asian presence on the network as unreliable and chaotic. It seemed that in making design choices—for example, reducing visual clutter and employing a “natural” 3-D image model—internet cartographers had risen to the challenge of representing complex communications data sets but ignored the challenge of representing complex histories.

The cluttered politics of cartography had, in the same period, been treated with sensitivity by historians and geographers such as Martin Lewis and Kären Wigen, whose 1997 book The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography called for new cartographic representations of regions and nations. Mapping colored blocks of nations on maps, they pointed out, implied a nonexistent uniformity across that space. Noting that “in the late twentieth century the friction of distance is much less than it used to be; capital flows as much as human migrations can rapidly create and re-create profound connections between distant places,” they critiqued the common-sense notions of national maps, because “some of the most powerful sociospatial aggregations of our day simply cannot be mapped as single, bounded territories.”11 Borrowing the term “metageography” from Lewis and Wigen, Harpold coined the term “internet metageographies.” He demonstrated how a variety of 1990s’ internet maps obscured transnational historical complexities, reified certain kinds of political hegemony, and reinscribed colonial tropes in popular network narratives. Thus, the apparently innocent use of light and dark color coding, or higher and lower planes, to represent the quantity of internet traffic relied for its intelligibility on Western notions of Africa as a dark continent or of Asia and Latin America as uniformly underdeveloped. The critique of traditional cartography came from a well-developed research field. But this historical and spatial scholarship seemed invisible or irrelevant to cartographers mapping the emergent digital domain.

“New media” narratives, seemingly taken up with the novelty of the technology, rewrote old stereotypes into renewed assumptions about viewers’ common-sense. Eick, Cox, and other famous technical visualizers had, in trying to build on viewers’ familiarity with airline routes and outlines of nations, inadvertently reproduced outdated assumptions about global development. Colonial stereotypes seemed to return, unchallenged, in digital discourses, despite the strong ways in which they had been challenged in predigital scholarship on media and science. Harpold concluded: “these depictions of network activities are embedded in unacknowledged and pernicious metageographies—sign systems that organize geographical knowledge into visual schemes that seem straightforward but which depend on the historically and politically-inflected misrepresentation of underlying material conditions.”12

These “underlying material conditions” of global communications have a long history. Harpold’s argument invoked a contrast between “beacons of light” and internet cables. In other words, he implied that the arcs of light used to represent internet traffic recalled a familiar narrative of enlightenment and cultural advancement, whereas a mapping of material infrastructure and cartographic histories might have helped build a different narrative.

Harpold hoped, at the time, that investigations of the internet’s “materiality” would give us details that might displace colonial and national metanarratives. How do new politics accrete to the cluster points where cables transition from sea to land? How do older geographies of power shape the relations of these nodes to the less-connected hinterlands? Such grounded research would, he hoped, remove the racial, gendered, nationalist cultural assumptions that shaped a first generation of internet maps.

We did indeed get a host of stories about materiality in the decade that followed. Yet our stories about race, gender, and nation did not seem to change as radically as the technologies these stories described. The next two sections explore some influential understandings about communication infrastructures. We find that an emphasis on material infrastructure might be necessary but not sufficient to achieve technologically and historically accurate representations of the internet.

The Internet as a Set of Tubes: Virtual and Material Communications

In 2006, United States Senator Ted Stevens experienced an unexplained delay in receiving email. In the predigital past, mail delays might have been due to snow, sleet, or sickness—some kind of natural or human unpredictability. But such problems were supposed to be obsolete in the age of the internet.

Stevens suggested that the structure of the internet might be causing his delay: “They want to deliver vast amounts of information over the internet . . . [But] the internet is not something you just dump something on. It’s not a truck. It’s a series of tubes.”13

Younger, geekier Americans erupted in hilarity and in outrage. Memes proliferated, mocking the Republican senator’s industrial metaphor for the virtual world, his anachronistic image revealing, some suggested, the technological backwardness of politicians. Tech pundit Cory Doctorow blogged about Senator Stevens’s “hilariously awful explanation of the Internet”: “This man is so far away from having a coherent picture of the Internet’s functionality, it’s like hearing a caveman expound on the future of silver-birds-from-sky.”14

The image of information tubes seemed to belong to a “caveman era” in comparison to the high-speed virtual transmission of the information era. For Doctorow, as for many technology analysts, we needed metaphors that conveyed the virtual scope, rather than the material infrastructure, of information technologies. The Stevens event hit many nerves, intersecting with national debates about net neutrality and technology professionals’ anger at a conservative agenda that was perceived as stalling the progress of technological modernity.15

But are pipes and tubes really such terrible images with which to begin a conversation about the operation of the internet? Tubes summon up an image not far from the actual undersea cables that really do undergird nearly speed-of-light communication. Although Stevens’s tubes seemed drawn from an industrial-era playbook, fiber optics, which enabled speed-of-light transmission by the end of the twentieth century, are tube-like in their structure. Their size, unlike industrial copper cable, is on the order of 50 microns in diameter. Cables a millimeter in diameter can carry digital signals with no loss. But fiber optics are not plug-and-play modules; virtual connections are not created simply by letting light flow along them. Engineers and network designers must figure out how many strands to group together, what material they must be clad in, how to connect several cables over large distances, where to place repeaters, and how to protect them from the elements. The infrastructure of tubes remains grounded in materials science and the detailed geographies of land and sea.16

At the end of the twentieth century, public discourse valorized images of information’s virtuality, rather than its materiality.17 The notion of an invisible system that could move information instantaneously around the universe was thrilling to people who thought of industrial technology as slow and inefficient. The promise of the digital was in its clean, transparent, frictionless essence. Internet visionaries were inspired by the new information technologies’ ability to transcend the physical constraints and linear logics of the industrial age. This was a new age; metaphors of pipes and tubes threatened to drag technological imaginations backward to a past full of cogs and grease.

Tubes also recall a century-old manner of delivering mail, when canisters literally shot through pneumatic tubes. Post-office worker Howard Connelly described New York’s first pneumatic mail delivery on October 7, 1897, in Fifty-Six Years in the New York Post Office: A Human Interest Story of Real Happenings in the Postal Service. He reported that the first canister contained an artificial peach and the second a live cat. Megan Garber, writing for the Atlantic, commented: “The cat was the first animal to be pulled, dazed and probably not terribly enthused about human technological innovation, from a pneumatic tube. It would not, however, be the last.”18 In Connelly’s 1931 autobiography, and at the heart of the things that fascinated his generation, we see an exuberant imagination associated with material objects and the physical constraints of transporting them.

In the shift from physical to virtual mail, tubes fell out of public imagination, even though information tubes of a different kind were proliferating around the world. The 1990s were a boom time for internet cable laying. So, too, were the years after Edward Snowden’s 2013 disclosures about NSA surveillance, which spurred many nations to start ocean-spanning cable projects, hoping to circumvent US networks.

Undersea cable technology is not new; in the mid-nineteenth century, a global telegraph network depended on them. In the 1850s, undersea cables were made of copper, iron, and gutta-percha (a Malaysian tree latex introduced to the West by a colonial officer of the Indian medical service). A century later, they were coaxial cables with vacuum tube amplifier repeaters. By the late twentieth century, they were fiber optics. By 2015, 99 percent of international data traveled over undersea cables, moving information eight times faster than satellite transmission.19 Communication infrastructure has looked rather like tubes for a century and a half.

Infrastructural narratives had been pushed to the background of media consumer imaginations in the 1990s, their earthly bounds overlooked in preference to the internet’s seemingly ethereal power. Internet service providers and their advertisers attracted consumers with promises of freedom from the constraints of dial-up modems and data limits. Influential media theory explored the new imaginations and cultural possibilities of virtuality. The space of the virtual seemed to fly above the outdated meatspace problems of justice, race, and gender.

These metaphors and analyses were not limited to those who designed and used the early internet. They began to shape influential models of the economic and cultural world. Mark Poster, one of the first humanists to analyze the internet as a form of “new media,” argued that the internet’s virtual world inaugurated a new political economy. In the industrial era, economists had measured labor via time spent in agrarian work or assembly-line labor. But in the global, technologically mediated world, he argued in 1990, “Labor is no longer so much a physical act as a mental operation.”20 Poster pioneered the theorization of virtual labor, politics, and culture.

In the 1990s, scholarship, media, and common sense all told us that we were living in a new, virtually mediated mental landscape. To the extent that the virtual power of the internet, and thus of internet-enabled dispersed global production, appeared to fly above industrial-era pipes, tubes, cogs, and other material constraints, it appeared that internet-enabled labor was ushering in a new Enlightenment. This new technological revolution seemed to immerse Western workers in a far denser global interconnectivity than that of their eighteenth-century European ancestors, thus appearing to shape more complex networked subjectivities. But to the extent that Third Worlders still appeared to live in an industrial-era economy, their subjectivities appeared anchored to an earlier point in European history.21 In other words, these narratives made it seem as if people in poorer economies were living in the past, and people in high-bandwidth richer societies were accelerating toward the future.

The Internet’s Geographic Imaginaries

It sounds crazy, but Earth’s continents are physically linked to one another through a vast network of subsea, fiber-optic cables that circumnavigate the globe.

—CNN Money, March 30, 2012

The financial dynamics of the global economy were radically reshaped by the seemingly instantaneous digital transmission of information. Financial trading practices experienced quantum shifts every time a faster cable technology shaved nanoseconds off a transaction. Despite the centrality of information tubes to their 2012 audience, CNN Money writers sought to capture everyman’s incredulous response to the discovery of a material infrastructure undergirding the virtual world: “crazy!”22 This 2012 news item suggests that the assumption that the internet was “virtual” persisted into the second decade of the new millennium. This was part of a now-common narrative convention that tended to emphasize “surprise” at finding evidence of materiality underpinning virtual experiences in cyberspace, a space conceived of as free from territorial and historical constraints.

Despite metaphors such as “information superhighway,” which seemed to remediate metaphors of physical road-building that recalled the infrastructural nineteenth century, a twenty-first-century American public, including many critical humanist academics, had come to rely on a set of metaphors that emphasized virtual space. The promise of cyberspace in its most transcendent forms animated a range of Euro-American projects, from cyberpunk fiction to media studies. Virtuality was, of course, tied to cultures with robust infrastructures and high bandwidth.

One magazine that prided itself on innovative technological reporting did, however, call attention to cables and material geographies as early as the mid-1990s. In December 1996, Wired magazine brought its readers news about a fiber-optic link around the globe (FLAG), under construction at the time. “The Hacker Tourist Travels the World to Bring Back the Epic Story of Wiring the Planet,” the cover announced, with an image of the travelogue author, superstar cyberpunk writer Neal Stephenson, legs spread and arms crossed, astride a manhole cover in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean,

The “Hacker Tourist” epic was the longest article Wired had published. The FLAG cable, at 28,000 kilometers, was the longest engineering project in history at the time. The cable, Stephenson predicted, would revolutionize global telecommunications and engineering. Well-known for his science fiction writing, Neal Stephenson wrote a technopredictive narrative that was accurate in all its major predictions: fiber-optic information tubes did in fact dramatically improve internet speeds.

The essay appealed to roughly the same kind of tech-savvy audience that found Ted Stevens’s metaphors caveman-like. Here was a cyberpunk writer, representing the future of the internet via metaphors of pipes and tubes. Two decades later, a leading Indian progressive magazine listed it among the “20 Greatest” magazine stories, crediting it for the revelation of “the physical underpinning of the virtual world.”23

This Is a Pipe: The Internet as a Traveling Tube

Stephenson introduces his “epic story” via a mapping narrative: “The floors of the ocean will be surveyed and sidescanned down to every last sand ripple and anchor scar.”24 The travelogue is filled with historical allusions. The opening page, for example, is structured in explicit mimicry of an Age of Exploration travel narrative. The essay’s opening foregrounds “Mother Earth” and the cable, the “mother of all wires,” and celebrates “meatspace,” or embodied worlds. The grounding of the story in “Earth” appears to subvert virtuality’s abstraction, and the term “meatspace” appears to invert a common dream of uploading of user consciousness to a disembodied “computer.”

Like Cory Doctorow in the pipes-and-tubes episode, Stephenson draws a contrast between industrial past and digital future. Unlike Doctorow, though, Stephenson celebrates pipes and tubes, or materiality, rather than virtuality. Stephenson successfully brought attention to the internet’s materiality in a decade otherwise obsessed with the virtual and drew in the history of colonial cable routes. It might seem, then, that Stephenson’s essay addresses what Terry Harpold identified as the need for materialist narratives of the internet.

Known for the deep historical research he puts into his fiction writing, Stephenson ironically emulates the stylistics of early modern explorers, describing experiences among “exotic peoples” and “strange dialects.” All the cable workers we see are men, but they are depicted along a familiar nineteenth-century axis of masculinity. The European cable-laying workers are pictured as strong, active, uncowed by the scale of the oceans. A two-page photo spread emphasizes their muscled bodies and smiling, confident faces, standing in neoprene wetsuits beside their diving gear on a sunny beach. Their counterparts in Thailand and Egypt are pictured differently. Thai workers are photographed through rebar that forms a cage-like foreground to their hunched bodies and indistinct faces. A portly Egyptian engineer reclines, smoking a hookah.

The representation of non-Western workers as caged or lazy, the structure of the world map that recalls telegraph and cable maps, and the gendered metaphors of exploration and penetration are familiar to historians of empire. Scientific expeditions to the tropics in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries collected specimens, produced maps, and accumulated resources that were key to the explosion of post-Enlightenment scientific and technological knowledge. Stephenson interweaves this knowledge with global power. Colonial administrators and armies that later used the navigational charts produced by early expeditions, and administrative experiments from policing to census policy, relied on scientific expertise. Stephenson knows, and cheekily redeploys, the historians’ insight that Enlightenment science and colonial exploration were mutually constitutive. The language of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century science plays with and rigidifies dichotomies between male-gendered workers and female-gendered earth, emasculated Eastern men and tough Western men, modernity’s feminizing effects and technology’s remasculinizing potential.25 These stereotypes originated in nineteenth-century European popular culture and science writing.

Harpold, a cultural critic of technology, had called for an account of materiality as a corrective to what he saw as the semiotic excess in early internet maps. But, as we see in Stephenson’s “Hacker Tourist” epic, an emphasis on the internet’s materiality doesn’t eliminate the racial, gender, and colonial resonances from narratives about it. Rather, the sustained popularity of this hacker travelogue was bound up in the frisson of historical recognition, and approval, with which readers greeted its mash-up of nineteenth-century gendered, raced, and colonial tropes.

In the two decades after Stephenson’s travelogue, infrastructure studies boomed in science and technology studies, anthropology, and media studies. These studies further reveal that infrastructure does not provide an escape from politics and history. For example, infrastructure scholars Bowker and Star described the links between infrastructure and historicity in a founding moment of this field: “Infrastructure does not grow de novo; it wrestles with the inertia of the installed base and inherits strengths and limitations from that base. Optical fibers run along old railroad lines, new systems are designed for backward compatibility; and failing to account for these constraints may be fatal or distorting to new development processes.”26

Some critics of the “cultural turn” in technology studies, recoiling at the disturbing historical and political history that seem to be uncovered at every turn, yearned for a return to empirical, concrete studies. For a moment, the focus on materiality and nonhuman actors seemed to offer this.27 But neither Neal Stephenson’s deep dive to the Atlantic Ocean floor nor the rise of “infrastructure studies” yielded clean stories about matter untouched by politics. It seemed to be politics all the way down.

Even as Stephenson waxed eloquent about the new Western infrastructure that was bringing freedom to the world, US news media outlets were filled with reports of a different wave of economic globalization. There was a global shift afoot that in the next decade would alter the economic grounds of this technocolonialist discourse.

Other Infrastructures

The consortium of Western telecom companies that undertook the massive, adventurous cable-laying venture Stephenson described encountered the digital downturn at the end of the 1990s, going bankrupt during the dot-com bust of 2000.28 India’s telecom giant Reliance bought up FLAG Telecom at “fire-sale prices” at the end of 2003. By 2010, there were about 1.1 million kilometers of fiber-optic cable laid around the globe. By 2012, the Indian telecommunications companies Reliance and Tata together owned “20% of the total length of fiber-optic cables on the ocean floor and about 12% of high-capacity bandwidth capacity across the globe.”29 In the year 2000, the fifty-three-year-old postcolonial nation’s popular image was of an underdeveloped economy that successfully used computational technology to leapfrog over its historical legacy of underdevelopment.30

Many internet narratives of the 1990s—incorporating assumptions about “advanced” and “backward” stages of growth, light and dark regions of the world, actively masculine and passively feminized populations, and so on—had pointed to real disparities in access to networks, or the “digital divide.” But they missed the ways in which the developing world was responding to this challenge by accelerating infrastructure development.

Another economic downturn hit the US in 2008. After Edward Snowden’s 2013 allegations about NSA surveillance, Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff declared the need to produce independent internet infrastructure. The US responded with allegations that Rousseff was embarking on a socialist plan to “balkanize” the internet. Al Jazeera reported that Brazil was in the process of laying more undersea cable than any other country, and encouraging the domestic production of all network equipment, to preclude the hardware “backdoors” that the NSA was reported to be attaching to US products: “Brazil has created more new sites of Internet bandwidth production faster than any other country and today produces more than three-quarters of Latin America’s bandwidth.”31

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, information’s pipes and tubes returned to the headlines. The “BRICS” nations—Brazil, India, China, and South Africa—were jumping over stages of growth, confounding the predictions of development experts. They were increasingly hailed as the superheroes of a future technological world, rather than disparaged as examples of the dismal failures of development and decolonization.

The rise of Asian technology manufacture and services and the shifting domain of economic competition regularly makes headlines and bestseller lists. The 1990s had brought Indian data-entry workers to the global stage through the Y2K crisis. Western corporations, finding skilled computer professionals who fixed a programming glitch for a fraction of the cost of Western labor rates, did not want to give up the valuable technological labor sources they had discovered. Software “body shopping” and outsourced technical labor grew significantly in the decade following Y2K. By 2015, Asian countries had taken the global lead by most indicators of economic progress, particularly in the technical educational readiness of workforces and in infrastructural and technical support for continued development. Yet global political and economic shifts in technology had not permeated popular Western images of information transmission.

There is a representational lag in Western writing about the state of non-Western technological practice. Despite the shifts in technological expertise, ownership, and markets, and the undeniable force of the former colonial world in the technological economy, Western representations of global information and telecommunications systems repeatedly get stuck in an anachronistic discursive regime.

Technology Is People’s Labor

Despite the shift in the ownership of cable and the skilled labor force, Euro-American representations of non-Western workers still recall the hunched-over, lazy colonial subjects that we encountered in Neal Stephenson’s ironic replay of nineteenth-century travelogues. By the 2010s, the “material infrastructure” versus “virtual superstructure” split was morphing into debates over “rote/automatable tasks” versus “creative thinking.”

Informatics scholar Lilly Irani has argued that “claims about automation are frequently claims about kinds of people.”32 She calls our attention to the historical conjunctures in 2006, when Daniel Pink’s bestseller, A Whole New Mind, summoned Americans to a different way of imagining the future of technological work. In the process, he identified “Asia” as one of the key challenges facing Western nations.33 Pink, comparing a computer programmer’s wage in India with the US ($14,000 versus $70,000), suggests that we abandon boring technical jobs to the uncreative minds of the developing world while keeping the more creative, imaginative aspects of technology design in Western hands. The problem of Asia, he notes, is in its overproduction of drone-like engineers: “India’s universities are cranking out over 350,000 engineering graduates each year.” Predicting that “at least 3.3 million white-collar jobs and $136 billion in wages will shift from the US to low-cost Asian countries by 2015,” Pink calls for Western workers to abandon mechanical, automaton-like labor and seek what he called “right brain” creative work. In this separation, we see the bold, active imaginations of creative thinkers contrasted with the automaton-like engineer steeped in equations and arithmetic. Irani reminds us of the historical context for this policy-oriented project: “The growth of the Internet . . . had opened American workers up to competition in programming and call center work. . . . Pink’s book A Whole New Mind was one example of a book that stepped in to repair the ideological rupture.”34

The binaries and geographies associated with Pink’s project have shaped policies and plans for design education and infrastructure development in the US. How are Pink’s predictions about “creative” tech design dependent on the narratives that excite him (imaginative, creative “design thinking” about technology) and the images that frighten him (hordes of technological experts speaking unknown languages, hunched over keyboards)? What implications do his visions of information design and creativity have for global infrastructure development and technical training? How do Pink’s fears draw on two centuries of anxiety about colonial subjects and their appropriation of Western science?35

This Is Not a Pipe: Alternative Materialities

Let us return to pipes, tubes, and those now-creaky but still-utopian internet imaginaries.

In an ethnographic study of the internet that uncovers rather different human and technical figures from Neal Stephenson’s travelogue, engineer/informatics scholar Ashwin Jacob Mathew finds that the internet is kept alive by a variety of social and technical relationships, built on a foundation of trust and technique.36 Mathew’s story retains Stephenson’s excitement about the internet but sets it in a decentered yet politically nuanced narrative, accounting for differences between the US and South Asia, for example, through the details of technical and political resources, rather than via racial essences and gendered stereotypes. In his 2014 study titled “Where in the World Is the Internet?,” he describes the social and political relationships required to bring order to the interdomain routing system: we find established technical communities of network operators, organized around regional, cross-national lines; nonprofit, corporate, and state-run entities that maintain internet exchange points; and massive scales across which transnational politics and financial support make the continual, apparently free, exchange of information possible. He tells a dynamic human and technical story of maintaining the minute-by-minute capacities of the internet, undergirded by massive uncertainties but also by cross-national, mixed corporate-state-community relationships of trust.

Risk and uncertainty in interdomain routing provide part of the justification for trust relationships, which can cut across the organizational boundaries formed by economic and political interests. However, trust relationships are more than just a response to risk and uncertainty. They are also the means through which technical communities maintain the embeddedness of the markets and centralized institutions involved in producing the interdomain routing system. In doing so, technical communities produce themselves as actors able to act “for the good of the internet,” in relation to political and economic interests.37

Infrastructures, Mathew reminds us, are relations, not things.38 Drawing on feminist informatics scholar Susan Leigh Star, and using his ethnography of network engineers to articulate how those relations are always embedded in human history and sociality, Mathew distinguishes his analysis from that encapsulated in John Perry Barlow’s 1996 A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. Avowing that the internet does offer radical new social possibilities, he suggests that these are not because it transcends human politics but rather because it is “actively produced in the ongoing efforts and struggles of the social formations and technologies involved in the distributed governance of Internet infrastructure.”39

Mathew’s aim is “to uncover the internal logic of the production of the virtual space of the Internet, and the manner in which the production of virtual space opposes and reconciles itself with the production of the spaces of the nation state, and the spaces of capital.”40 His study begins with a methodological question as original as Stephenson’s. While Stephenson follows a cable ethnographically, Mathew asks: how can one study a protocol ethnographically? In his exploration of the Border Gateway Protocol and the maintenance labor that goes into internet exchange points, he offers us a more complex narrative of the internet. Both authors follow a technological object that cannot be pinned down to one point in space and time. Stephenson circumscribes this nebulous object of study in classic 1980s cyberpunk style, but globalism has changed its face since then. We need new narratives and new questions that acknowledge the internet’s non-Western geographies, and Mathew’s is just one of the various global voices that depart radically from internet models of the late twentieth century.

Two other internet mappers from the changing contexts of twenty-first-century narratives offer images of the production of virtual spaces. These, it turns out, look nothing like the one-way pipes of 1990s internet maps nor the imperial telegraph cables of the nineteenth century. Internet artists have articulated refreshingly complex and refractory models of the internet in the first decade of the twenty-first century, replaying but modifying the cartographies of the 1990s.

Artist Barrett Lyon’s Opte Project (opte.org) offers a visualization of the routing paths of the internet, begun in 2003 and continually updated, allowing a time line of dynamic images of decentered globalization patterns (fig. 4.2). Lyon describes the Opte Project as an attempt to “output an image of every relationship of every network on the Internet.” This is rather different from Cox and Eick’s 1995 aesthetic parsimony. Compared to 1990s internet visualizations, which attempted to eliminate confusion and excessive lines, Lyon’s approach seems to revel in the excess of data. This design choice is largely attributable, of course, to the massive increase in computational power in the decade or so after Cox and Eick’s first visualization schemas. The ability to display massive data sets to viewers fundamentally alters the historical and geographical picture brought by designers to the general public. Lyon’s visualizations retain maximalist forms of route data, incorporating data dumps from the Border Gateway Protocol, which he calls “the Internet’s true routing table.” The project has been displayed in Boston’s Museum of Science and New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. Lyon reports that it “has been used an icon of what the Internet looks like in hundreds of books, in movies, museums, office buildings, educational discussions, and countless publications.”41

Figure 4.2 Barrett Lyon’s internet map (2003).

Artist Benjamin De Kosnik offers an idiosyncratic imaging of the internet in a collaborative digital humanities project called Alpha60. Beginning with a case study mapping illegal downloads of The Walking Dead, he proposes, with Abigail De Kosnik, to develop Alpha60 into “a functional ratings system for what the industries label ‘piracy.’” Tracking, quantifying, and mapping BitTorrent activity for a range of well-known US TV shows, De Kosnik and De Kosnik analyze images of the world that are both familiar (in that they confirm common-sense ideas about piracy and the diffusion of US popular culture) and surprising (in that they demonstrate patterns of activity that contradict the 1990s model of wired and unwired nations, bright ports and dark hinterlands, and other nation-based geographic metaphors for connectivity). This has immediate critical implications for media distribution. They write: “We do not see downloading activity appearing first in the country-of-origin of a television show . . . Rather, downloading takes place synchronously all over the world. . . . This instantaneous global demand is far out of alignment with the logics of the nation-based ‘windowing’ usually required by international syndication deals.”42 In a data-driven, tongue-in-cheek upending of conventional media policy, they show how “over-pirating” happens in concentrations of a “global tech elite.” They overturn our assumptions about where piracy occurs, suggesting that the development and deployment of technology in the West often goes hand-in-hand with practices that disrupt inherited ethical and legal norms, but elite disruption doesn’t generate the same kind of criminal stereotypes as poor people’s pirating.

The internet itself was not one thing in the 1990s. Its shift away from a defense and research backbone toward a public resource via the development of the World Wide Web is a military-corporate history that explains some of the confusion among media narratives. And technological freedom did not bring freedom from history and politics. The internet looks like a pipe in many places, but it moves along a radically branching structure and it is powered by human labor at all its exchange points. In the 1990s, internet narratives gave us a picture of a pipe constructed from colonial resources and bolstered by imperialist rhetoric, but, in more recent research, it appears to be uneven, radically branched, and maintained by a world of diverse people.

The internet is constituted by entangled infrastructural and human narratives that cannot be understood via separate technological and humanistic histories. The historical forces that simultaneously shaped modern ontological assumptions about human difference and infrastructures of technological globalization are alive today. Racial, gendered, and national differences are embedded, in both familiar and surprising ways, in a space that John Perry Barlow once described as a utopia free from the tyranny of corporate and national sovereignty. With sympathy for Barlow’s passionate manifesto for cyberspace’s independence from the prejudices of the industrial era (“We are creating a world that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth,” he announced in Davos in 1996),43 this chapter recognizes, also, that we cannot get there from here if we uncritically reuse the narratives and technologies thus far deployed by the internet’s visionaries, bureaucrats, builders, and regulators.

Adding universalist human concerns to a globalizing internet infrastructure (as well-meaning technology planners suggest) is not sufficient. Engaged scholars and designers who wish to shape future openness in internet infrastructures and cultures need to do more than affirm an abstract humanism in the service of universal technological access. Racial, gendered, and nationalist narratives are not simply outdated vestiges of past histories that will fall away naturally. They are constantly revivified in the service of contemporary mappings of materials, labor, and geopolitics. The internet is constantly being built and remapped, via both infrastructural and narrative updates. The infrastructural internet, and our cultural stories about it, are mutually constitutive.

The internet’s entangled technological and human histories carry past social orders into the present and shape our possible futures. The concrete, rubber, metal, and electrical underpinnings of the internet are not a neutral substrate that enable human politics but are themselves a sedimented, multilayered historical trace of three centuries of geopolitics, as well as of the dynamic flows of people, plants, objects, and money around the world in the era of European colonial expansion. We need new narratives about the internet, if we are to extend its global infrastructure as well as diversify the knowledge that it hosts.

But first we must examine the narratives we already inherit about the internet and about information technology. Many of us still think of information technology as a clean, technological space free from the messiness of human politics. Clean technological imaginaries, free of politics, can offer a tempting escape from history’s entanglements and even facilitate creative technological design in the short run. But embracing the messiness, this chapter suggests—acknowledging the inextricability of the political and the digital—might enable better technological and human arrangements.

The ideas that excite artists like Benjamin De Kosnik and Barrett Lyon and media/technology scholars like Abigail De Kosnik and Ashwin Jacob Mathew, and the internet models that undergird this new research, are rather different from those that animate Daniel Pink’s global economic forecasts, Stephenson’s material-historical cyberpunk metaphors, or Cory Doctorow’s optimism about virtuality. As varied as the latter Western representations were at the turn of the twentieth century, they have already been surpassed by the sheer complexity, unapologetic interdisciplinarity, and transnational political nuance that characterize a new generation of global internet analysts.

Power’s Plumbing

From claims about the “colonial” internet in the early twenty-first century, this chapter has led us backward in time. In order to understand why the Wikimedia Foundation found itself allied with decolonial social movements,44 we broadened our story. Concerns about social justice and decolonization have begun to shape many of the new analyses not just about the internet and its participants but about all internet-driven data. The “decolonial” urge to democratize the production, dissemination, and ownership of knowledge has proved inextricable from material understandings of the internet. Thus we moved from statistics about identities of users and producers of online knowledge to infrastructural issues about who lays, maintains, and owns the infrastructures (servers, cables, power, and property) that enable this medium, as well as representational strategies by which we map and weave together human and technological narratives.

We have seen how forms of representation of information online are inseparable from the material histories of communication. Older, colonial-era infrastructures predated and enabled twentieth-century cable-laying projects. Geopolitics as well as undersea rubble repeatedly break cables or shift routing paths. Representational inequities cycle into policy-making about regulating access to knowledge. Once seen as a neutral technological affordance, the internet is increasingly beginning to be understood as a political domain—one in which technology can enhance some kinds of political power and suppress others, radically shifting our notions of democratic public sphere. Celebrating this new technology that set the world on fire in the late twentieth century, this chapter seeks not simply to tar it with the brush of old politics but to ask how this fire, in all its social, political, and technological aspects, can be tended in the interests of an increasingly diverse global community of users.

As in Sarah Roberts’s chapter (“Your AI Is a Human”), it turns out that the infrastructural internet and the creators of its imaginaries are connected by the labor of global humans. Like Nathan Ensmenger (“The Cloud Is a Factory”) and Benjamin Peters (“A Network Is Not a Network”), I turn to the history of the material, infrastructural view of the internet—a version of the internet’s origin story that was once articulated primarily by infrastructural engineers.45 But we found that there’s more than infrastructure at play here. As Halcyon Lawrence (“Siri Disciplines”) and Tom Mullaney (“Typing Is Dead”) suggest, nonwhite users are increasingly resisting the imperial norms that shape our internet-related practices. National histories and imperial politics help select the stories we tell about the internet’s past, as well as shape what we can do with its future. Seeing this requires skills in analyzing metaphor, narrative, and social history. We find that the separation of technical and cultural skills has produced knowledge that impedes the integrated improvement of technical design and use. As decolonial technological activism grows, the power dynamics involved in this historical separation of technology and culture will come under intense political and cultural scrutiny.

To revalue and resituate both technical and humanist knowledge, we need to find better ways to teach multiple kinds of skills in media, information, and computer science’s educational and practical contexts. We need stories that showcase the irreducibly political realities that make up the global internet—the continual human labor, the mountains of matter displaced, its diverse material and representational habitats. Acknowledging that the political and the digital cannot be separated might serve as an antidote against the seductive ideal of technological designs untouched by the messiness of the real world. Examining the historical underpinnings of our common-sense understandings of the internet can lead us to insights about the ways in which we shape ourselves as modern, globally connected technological designers and users. Using this historical/technical lens, we are able to ask questions about the plumbing of power implicit in every internet pipe: who labored on these connections, who owns them, who represents them, who benefits from them? Tracing these things, their maintenance, as well as their shifting cultural understandings reveals the myriad ways in which the internet is already being decolonized.

Notes

1. Julia Jaki, “Wiki Foundation Wants to ‘Decolonize the Internet’ with more African Contributors,” Deutsche Welle (July 19, 2018), https://www.dw.com/en/wiki-foundation-wants-to-decolonize-the-internet-with-more-african-contributors/a-44746575.

2. Whose Knowledge?, accessed August 1, 2018, https://whoseknowledge.org/decolonizing-the-internet-conference/.

3. See, for instance, Martin Macias Jr., “Activists Call for an End to LA’s Predictive Policing Program,” Courthouse News Service (May 8, 2018), https://www.courthousenews.com/activists-call-for-an-end-to-las-predictive-policing-program/; the work of the activist “Stop LAPD Spying Coalition,” https://stoplapdspying.org/; and the activist-inspired academic work of the Data Justice Lab at Cardiff, https://datajusticelab.org.

Decolonial history and theory shape data analysis in Nick Couldry and Ulises Ali Mejias, The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), accessed August 16, 2019, https://colonizedbydata.com/.

4. On the politicization of developing-country data, see Linnet Taylor and Ralph Schroeder, “Is Bigger Better? The Emergence of Big Data as a Tool for International Development Policy,” GeoJournal 80, no. 4 (August 2015): 503–518, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-014-9603-5, and Morten Jerven, Poor Numbers: How We Are Misled by African Development Statistics and What to Do about It (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2013).

5. Overall, connectivity has increased in Africa in the twenty-first century, but it remains uneven and tied to national and colonial histories. International Telecommunications Union (ITU) statistics offer us a snapshot: Between 2000 and 2017, internet connectivity in Angola increased from 0.1% to 14% of the population, in Somalia from 0.02% to 2%, in South Africa from 5% to 56%, and in Zimbabwe from 0.4% to 27%. In the US, internet connectivity grew from 43% to 87% in the same period. ITU Statistics (June 2018 report on “Country ICT Data 2000–2018),” https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/facts/default.aspx. Statistics cited from ITU Excel spreadsheet downloaded August 15, 2019.

6. P. J. Hugill, Global Communications since 1844: Geopolitics and Technology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 2.

7. Hugill, Global Communications since 1844, 18.

8. Susan Leigh Star and Geoff Bowker, Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999).

9. Kenneth C. Cox and Stephen G. Eick, “Case Study: 3D Displays of Internet Traffic,” in Proceedings on Information Visualization (INFOVIS ’95) (1995), 129.

10. For an overview of internet maps, see “Beautiful, Intriguing, and Illegal Ways to Map the Internet,” Wired (June 2015), https://www.wired.com/2015/06/mapping-the-internet/. Spatial/technology mapping has evolved into a tool critical to business logistics, marketing, and strategy, see e.g. https://carto.com/, accessed August 15, 2019.

11. Martin W. Lewis and Kären E. Wigen, The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 200.

12. Terry Harpold, “Dark Continents: A Critique of Internet Metageographies,” Postmodern Culture 9, no. 2 (1999), https://doi.org/10.1353/pmc.1999.0001.

14. Cory Doctorow, “Sen. Stevens’ hilariously awful explanation of the Internet,” BoingBoing (July 2, 2006), https://boingboing.net/2006/07/02/sen-stevens-hilariou.html.

15. Princeton professor Ed Felten paraphrased Stevens’s quote as: “The Internet doesn’t have infinite capacity. It’s like a series of pipes. If you try to push too much traffic through the pipes, they’ll fill up and other traffic will be delayed.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Series_of_tubes.

16. For the range of technical concerns that go into the cable’s material and physical structure, see, e.g., https://www.globalspec.com/learnmore/optics_optical_components/fiber_optics/fiber_optic_cable.

17. The virtuality/materiality divide was vigorously debated in informatics and science and technology studies. Infrastructure analysis was pioneered by feminist scholars. See, e.g., Lucy Suchman, Human-Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Katherine N. Hayles, Writing Machines (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002); Susan Leigh Star and Odense Universitet, Misplaced Concretism and Concrete Situations: Feminism, Method and Information Technology (Odense, Denmark: Feminist Research Network, Gender-Nature-Culture, 1994); Paul Duguid, “The Ageing of Information: From Particular to Particulate,” Journal of the History of Ideas 76, no. 3 (2015): 347–368.

18. Howard Wallace Connelly, Fifty-Six Years in the New York Post Office: A Human Interest Story of Real Happenings in the Postal Service (1931), cited in Megan Garber, “That Time People Sent a Cat Through the Mail,” Atlantic (August 2013), https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/08/that-time-people-sent-a-cat-through-the-mail-using-pneumatic-tubes/278629/.

19. Data from TeleGeography, https://www2.telegeography.com/our-research. TeleGeography’s assessment of 99% of all international communications being carried on undersea fiber optic cables was also reported by the “Builtvisible” Team in “Messages in the Deep” (2014), https://builtvisible.com/messages-in-the-deep/. For an ethnogeography of these cables, explicitly inspired by Neal Stephenson’s cable travelogue, see Nicole Starosielski, The Undersea Network (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015). For continuing updates on cable technology, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Submarine_communications_cable.

20. Mark Poster, The Mode of Information: Poststructuralism and Social Context (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 129.

21. Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014).

22. “A giant undersea cable makes the Internet a split second faster,” CNN Money (February 30, 2012). On remediated metaphors in the digital world, see Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003). For nineteenth-century metaphors in modern road-building, see America’s Highways 1776–1976: A History of the Federal Aid Program, Federal Highways Administration (Washington, DC: US Government printing Office, 1977).

23. “The 20 Greatest Magazine Stories,” Outlook Magazine, November 2, 2015, https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/the-20-greatest-magazine-stories/295660.

24. Neal Stephenson, “The Epic Story of Wiring the Planet,” Wired (December 1996), 160.

25. Neal Stephenson’s reinvention of Enlightenment science and travel narratives is more extensively explored in “‘Travel as Tripping’: Technoscientific Travel with Aliens, Gorillas, and Fiber-Optics,” Kavita Philip, keynote lecture, Critical Nationalisms and Counterpublics, University of British Columbia, February 2019.

26. Susan Leigh Star and Geoffrey Bowker, Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 35.

27. Severin Fowles, “The Perfect Subject (Postcolonial Object Studies),” Journal of Material Culture 21, no. 1 (March 2016), 9–27, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183515623818.

28. “The Dot-Com Bubble Bursts,” New York Times (December 24, 2000), https://www.nytimes.com/2000/12/24/opinion/the-dot-com-bubble-bursts.html.

29. High-capacity bandwidth is defined as 1 million Mbps or more. All data from consulting firm Terabit, reported by Economic Times (April 2012), http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2012-04-15/news/31342442_1_undersea-cable-submarine-cables-fibre.

30. J. P. Singh, Leapfrogging Development? The Political Economy of Telecommunications Restructuring (Binghamton: State University of New York Press, 1999).

31. Bill Woodcock, “Brazil’s official response to NSA spying obscures its massive Web growth challenging US dominance,” Al Jazeera (September 20, 2013); Sascha Meinrath, “We Can’t Let the Internet Become Balkanized,” Slate (October 14, 2013), http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2013/10/internet_balkanization_may_be_a_side_effect_of_the_snowden_surveillance.html.

32. Lilly Irani, “‘Design Thinking’: Defending Silicon Valley at the Apex of Global Labor Hierarchies,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 4, no. 1 (2018).

33. Daniel H. Pink, A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future (New York: Riverhead Books, 2006). Pink identifies “abundance, Asia, and automation” as the three key challenges to Western dominance of the global technological market.

34. Irani, “Design Thinking.”

35. The full import of these questions takes us outside the scope of this chapter’s interest in internet narratives. For an exploration of these, see Lilly Irani, Chasing Innovation: Entrepreneurial Citizenship in Modern India (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019), which offers a transnationally researched analysis of computational “design thinking” as a new imperial formation.

36. Ashwin Jacob Mathew, “Where in the World Is the Internet?,” PhD dissertation, School of Informatics, UC Berkeley, 2014.

37. Mathew, “Where in the World Is the Internet?”

38. Susan Leigh Star and Karen Ruhleder, “Steps toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces,” Information Systems Research 7, no. 1 (1996), 111–34.

39. Mathew, “Where in the World Is the Internet?,” 230.

40. Mathew, “Where in the World Is the Internet?,” 231.

41. Barrett Lyon, The Opte Project, opte.org/about, retrieved February 1, 2019. Archived at https://www.moma.org/collection/works/110263 and the Internet Archive, https://web.archive.org/web/*/opte.org.

42. Abigail De Kosnik, Benjamin De Kosnik, and Jingyi Li, “A Ratings System for Piracy: Quantifying and Mapping BitTorrent Activity for ‘The Walking Dead,’” unpublished manuscript, 2017.

43. John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” Davos, Switzerland, February 8, 1996, Electronic Frontier Foundation, https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-independence.

44. The Wikimedia Foundation supports efforts to decolonize knowledge because, simply, their claim to house the sum of all knowledge in the world has been shown, by social movements from the Global South, to be woefully incomplete. Like the “World” Series in baseball, it turned out that a national tournament had been erroneously billed as global. Recognizing “a hidden crisis of our times” in the predominance of “white, male, and global North knowledge” led to the forging of the world’s first conference focused on “centering marginalized knowledge online,” the Whose Knowledge? conference. Thus the Wikipedia project promises to go beyond its predecessor and original inspiration, the eighteenth-century encyclopedia project. See also https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Strategy/Wikimedia_movement/2017, retrieved August 1, 2018. Aspiring to create a “world in which every single human being can freely share in the sum of all knowledge,” the Wikimedia Foundation underwrites human and infrastructural resources for “the largest free knowledge resource in human history.”

45. The importance of the material underpinnings of virtual technologies is a thriving subfield in the humanities; see Susan Leigh Star, “The Ethnography of Infrastructure,” American Behavioral Scientist 43, no. 3 (1999): 377–391, https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326; and Tung-Hui Hu, A Prehistory of the Cloud (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016).