9

Your Robot Isn’t Neutral

Safiya Umoja Noble

Introduction

In my long-term research agenda, I have been mostly concerned with who benefits, who loses, and what the consequences and affordances are of emergent technologies, and now I am pointing these lenses from the fields of Black studies, gender studies, and critical information studies to the field of robotics.1 Recently, I’ve been thinking about the algorithmically driven software embedded in anthropomorphized computers—or humanlike robots—that will enter the market soon. My aim with this chapter is to offer a series of provocations and suggest that we continue to gather interdisciplinary scholars to engage in research that asks questions about the reinscribing of race and gender in both software and hardware.

One of the most fiery debates in contemporary society, particularly in the United States, is concerned with the treacherous implementation of racist ideologies and legal and social practices that structurally displace, demean, and deny rights to indigenous people, African Americans, Latinx communities, and immigrants from around the world, particularly Asian Americans, Southeast Asians, and Pacific Islanders. In fact, as this book goes to press, hate crimes and violence against the aforementioned groups have seen a significant uptick, fueled by viral vitriol disseminated with intense speed and in great volume by digital platforms and computing networks. How then will robotics be introduced into these fiery times, and with what kinds of consequences? These are the questions that lie before us, despite the notions of robotics existing somewhere between a new form of assistive and nonthreatening labor and autonomous droids that dominate humans. Unfortunately, as we grapple with competing cultural ideas about whether robots will be helpful or harmful, robotic devices are already being inscribed with troublesome ideas about race and gender. In fact, these concerns are intertwined with the ideas Halcyon Lawrence has raised in this book about language, dialects, and virtual assistants and only underscore how much is at stake when we fail to think more humanistically about computing.

Your Robot Is a Stereotype

In January of 2018, I had a novel experience of meeting with some of the leading women in the field of robotics in the United States, gathered by Professor Londa Schiebinger and the Gendered Innovations initiative at Stanford University to share research about the ways that gender is embedded in robotics research and development. One key takeaway from our meeting is that the field of robotics rarely engages with social science and humanities research on gender and race, and that social scientists have much to offer in conceptualizing and studying the impact of robotics on society. An important point of conversation I raised at our gathering was that there is a need to look closely at the ways that race and gender are used as hierarchical models of power in the design of digital technologies that exacerbate and obfuscate oppression.

At that Stanford gathering of women roboticists, the agenda was focused explicitly on the consequences and outcomes of gendering robots. Social scientists who study the intersection of technology and gender understand the broader import of how human beings are influenced by gender stereotypes, for example, and the negative implications of such. Donna Haraway helped us understand the increasingly blurred lines between humans and technology vis-à-vis the metaphor of the cyborg.2 More recently, Sherry Turkle’s research argued that the line between humans and machines is increasingly becoming indistinguishable.3 Jennifer Robertson, a leading voice in the gendering of robots, helps contextualize the symbiotic dynamic between mechanized technologies like robots and the assignment of gender:

Roboticists assign gender based on their common-sense assumptions about female and male sex and gender roles. . . . Humanoid robots are the vanguard of posthuman sexism, and are being developed within a reactionary rhetorical climate.4

Indeed, the ways that we understand human difference, whether racialized or gendered, is often actualized in our projections upon machines. The gender and robotics meeting left me considering the ways that robots and various forms of hardware will stand in as human proxy, running on scripts and code largely underexamined in their adverse effects upon women and people of color. Certainly, there was a robust understanding about the various forms of robots and the implications of basic forms of gendering, such as making pink versus blue robot toys for children. But the deeper, more consequential ways of thinking about how gender binaries are constructed and replicated in technologies that attempt to read, capture, and differentiate among “male” versus “female” faces, emotions, and expressions signal we are engaging territories that are rife with the problems of gendering.

The complexity of robots gendering us is only made more complicated when we engage in gendering robots. In the field of human–robot interaction (HRI), ideas about genderless or user-assigned gender are being studied, particularly as it concerns the acceptability of various kinds of tasks that can be programmed into robots who will interact with human beings across the globe. For example, questions as to whether assistive robots used in health care, who may touch various parts of the body, are studied to see if these kinds of robots are more easily accepted by humans when the gender of the robot is interpreted as female. Søraa has carefully traced the most popular commercial robots and the gendering of such technologies, and further detailed how the narratives we hold about robots have a direct bearing on how they are adopted, perceived, and engaged with. This is an important reason why gender stereotyping of robots plays a meaningful role in keeping said stereotypes in play in society. For example, Søraa deftly describes the landscape of words and signifiers that are used to differentiate the major commercial robotics scene, stemming largely from Japan, and how male and female androids (or “gynoids,” to use a phrase coined by Robertson) are expressions of societal notions about roles and attributes that “belong” or are native to binary, naturalized notions of biological sex difference.5

Robots run on algorithmically driven software that is embedded with social relations—there is always a design and decision-making logic commanding their functionality. If there were any basic, most obvious dimensions of how robots are increasingly embedded with social values, it would only take our noticing the choices made available in the commercial robotics marketplace between humanoid robotics and other seemingly benign devices, all of which encode racial and gender signifiers. To complicate matters, even the nonhumanlike (nonanthropomorphic) robotic devices, sold by global digital media platforms like Google, Apple, and Amazon, are showing up in homes across the United States with feminine names like Amazon’s Alexa or Apple’s Siri, all of which make “feminine” voices available to users’ commands.

Figure 9.1 Image of Microsoft’s Ms. Dewey, as researched by Miriam Sweeney.

The important work of Miriam Sweeney at the University of Alabama shows how Microsoft’s Ms. Dewey was a highly sexualized, racialized, and gendered avatar for the company (see fig. 9.1). Her Bitch interview about fembots is a perfect entry point for those who don’t understand the politics of gendered and anthropomorphized robots.6 It’s no surprise that we see a host of emergent robotic designs that are pointed toward women’s labor: from doing the work of being sexy and having sex, to robots that clean or provide emotional companionship. Robots are the dreams of their designers, catering to the imaginaries we hold about who should do what in our societies.

But what does it mean to create hardware in the image of women, and what are the narratives and realities about women’s labor that industry, and its hardware designers, seek to create, replace, and market? Sweeney says:

Now more than ever it is crucial to interrogate the premise of anthropomorphization as a design strategy as one that relies on gender and race as foundational, infrastructural components. The ways in which gender and race are operationalized in the interface continue to reinforce the binaries and hierarchies that maintain power and privilege. While customization may offer some individual relief to problematic representations in the interface, particularly for marginalized users, sexism and racism persist at structural levels and, as such, demand a shifted industry approach to design on a broad level.7

To Sweeney’s broader point, it’s imperative we go beyond a liberal feminist understanding of “women’s roles” and work. Instead, we need to think about how robots fit into structural inequality and oppression, to what degree capital will benefit from the displacement of women through automation, and how the reconstruction of stereotypical notions of gender will be encoded in gender-assigned tasks, free from other dimensions of women’s intellectual and creative contributions. Indeed, we will continue to see robots function as expressions of power.

Figure 9.2 Google image search on “robots.” (Source: Google image, February 8, 2018.)

Why Are All the Robots White?

In my previous work, I’ve studied the images and discourses about various people and concepts that are represented in dominant symbol systems like Google search (see fig. 9.2).8 Robots have a peculiar imaginary in that they’re often depicted as servile and benevolent. Often encased in hard white plastics, with illuminated blue eyes, they exist within the broader societal conceptions of what whiteness means as metaphor for what is good, trustworthy, and universal. White robots are not unlike other depictions where white or light-colored skin serves as a proxy for notions of goodness and the idealized human.

Racialized archetypes of good versus evil are often deployed through film and mass media, such as the film I, Robot (2004), starring Will Smith, which explores the ethics of robots while mapping the terrain and tropes of (dis)trust and morality in machines (see fig. 9.3).9 Drawing down on the racist logics of white = good and Black = bad, what is the robotics industry (and Hollywood, for that matter) attempting to take up in discussions about the morality of machines? Indeed, an entire new area of study, better known among roboticists as “machine morality,” must still contend with histories and cultural logics at play in design and deployment, and these seem to be well-studied and understood best in partnership with humanists and social scientists, for whom these ideas are not novel but extend for hundreds of years if not millennia.10 Indeed, despite computer scientists’ rejection of the humanities, these egregious notions of conceptually introducing machine morality into systems of racial and gender oppression are quite obviously prone to disaster to those humanists and social scientists who study the intersections of technology and the human condition. To be blunt, humans have yet to figure out and proactively resolve the immorality of racism, sexism, homophobia, occupation, ableism, and economic exploitation. It’s quite a wonder that roboticists can somehow design robots to contend with and resolve these issues through a framework of machine morality; indeed, we could certainly use these problem-solving logics in addressing extant human misery with, or without, robots.

Figure 9.3 Still image from the film I, Robot. (Source: https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/i-robot-2004.)

Your Robot’s “Brain” Is Running on Dirty Data

The digital is one powerful place where gendered and racialized power systems are obscured, because when artificial intelligence or automated decision-making systems discriminate against you, it is difficult to even ascertain what has happened. Automated discrimination is difficult to parse, even though there is clearly distinguished literature that has carefully documented how it works and how prevalent it is becoming. As Cathy O’Neil warns, it’s difficult to take AI to court or exert our rights over computer code and hardware.11 Of concern are the lack of clearly defined linkages between the making of data sets and the historical and social practices that inform their construction. For example, when data is developed from a set of discriminatory social processes, such as the creation of statistics on policing in a municipality, it is often impossible to recognize that these statistics may also reflect procedures such as overpolicing and disproportionate arrest rates in African American, Latinx, and low-income neighborhoods.12

Early work of educational theory scholar Peter Smagorinsky carefully articulates the dominant metaphors that are used with our conceptions of “data” that infer a kind of careful truth construction around purity and contamination, not unlike new frameworks of “biased” versus “objective” data:

The operative metaphors that have characterized researchers’ implication in the data collection process have often stressed the notion of the purity of data. Researchers “intrude” through their media and procedures, or worse, they “contaminate” the data by introducing some foreign body into an otherwise sterile field. The assumption behind these metaphors of purity is that the researcher must not adulterate the social world in which the data exist. . . . The assumption that data are pure implies that researchers must endeavor strongly to observe and capture the activity in a research site without disrupting the “natural” course of human development taking place therein.13

We must continue to push for a better, common-sense understanding about the processes involved in the construction of data, as evidenced by the emergent and more recent critiques of the infallibility of big data, because the notion that more data must therefore lead to better data analysis is incorrect. Larger flawed or distorted data sets can contribute to the making of worse predictions and even bigger problems. This is where social scientists and humanists bring tremendous value to conceptualizing the paradigms that inform the making and ascribing of values to data that is often used in abstract and unknown or unknowable ways. We know that data is a social construction as much as anything else humans create, and yet there tends to be a lack of clarity about such in the broad conceptualization of “data” that informs artificial decision-making systems. Often, the fact that data—which is the output on some level of human activity and thought—is not typically seen as a social construct by a whole host of data makers makes intervening upon the dirty or flawed data even more difficult.14

In fact, I would say this is a major point of contention when humanists and social scientists come together with colleagues from other domains to try to make sense of the output of these products and processes. Even social scientists currently engaging in data science projects, like anthropologists developing predictive policing technologies, are using logics and frameworks that are widely disputed as discriminatory.15 The concepts of the purity and neutrality of data are so deeply embedded in the training and discourses about what data is that there is great difficulty moving away from the reductionist argument that “math can’t discriminate because it’s math,” which patently avoids the issue of application of predictive mathematical modeling to the social dimensions of human experience. It is even more dangerous when social categories about people are created as if they are fixed and natural, without addressing the historical and structural dimensions of how social, political, and economic activities are shaped.

This has been particularly concerning in the use of historical police data in the development of said predictive policing technologies, which we will increasingly see deployed in a host of different robotics—from policing drones to robotic prison guards—where the purity and efficacy of historical police data is built into such technology design assumptions.

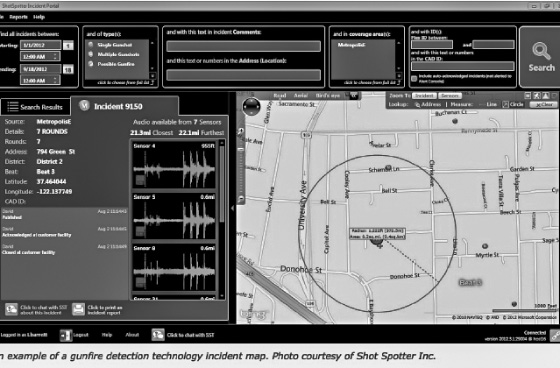

Typically, such products use crime statistics to inform processes of algorithmic modeling. The resulting output is a “prediction” of precise locations of future crime (see fig. 9.5).16 This software, already used widely by police agencies across the United States, has the potential to grow exponentially in its power and impact when coupled with robots, drones, and other mechanical devices. It’s important, dare I say imperative, that policy makers think through the implications of what it will mean when this kind of predictive software is embedded in decision-making robotics, like artificial police officers or military personnel that will be programmed to make potentially life-or-death decisions based on statistical modeling and a recognition of certain patterns or behaviors in targeted populations.

Crawford and Shultz warn that the use of predictive modeling through gathering data on the public also poses a serious threat to privacy; they argue for new frameworks of “data due process” that would allow individuals a right to appeal the use of their data profiles.17 This could include where a person moves about, how one is captured in modeling technologies, and use of surveillance data for use in big data projects for behavioral predictive modeling such as in predictive policing software:

Moreover, the predictions that these policing algorithms make—that particular geographic areas are more likely to have crime—will surely produce more arrests in those areas by directing police to patrol them. This, in turn, will generate more “historical crime data” for those areas and increase the likelihood of patrols. For those who live there, these “hot spots” may well become as much PII [personally identifiable information] as other demographic information.18

Figure 9.4 Predictive policing software depicting gunfire detection technology. (Source: Shot Spotter.)

In the case of predicting who the likely perpetrators of “terrorist crime” could be, recent reports on the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency’s predictive decision-making through its “Extreme Vetting Initiative” have been found to be faulty, at best.19 In fact, many scholars and concerned scientists and researchers signed a petition to Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and other key executives, expressing concern and signaling widespread condemnation among those who understand the potency and power of using such technologies in discriminatory ways.20 Their petition was in direct solidarity with Microsoft employees who objected to the use of Microsoft’s technology in the Azure Government platform that would be used to accelerate abuses of civil and human rights under policies of the Trump Administration, and it also amplified the work of Google employees who had rebuffed Google executives’ efforts to engage in Project Maven, a contract with the US Department of Defense to process drone footage used in military operations, another example of the melding of robotic technology (drones) with AI software meant to increase the potency of the product.21

Facial-recognition software is but one of the many data inputs that go into building the artificial backbone that bolsters predictive technologies. Yet there is alarming concern about these technologies’ lack of reliability, and the consequences of erroneously flagging people as criminals or as suspects of crimes they have not committed. The deployment of these AI technologies has been brought to greater scrutiny by scholars like computer scientists Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, whose research on facial-recognition software’s misidentification of women and people of color found that commercial technologies—from IBM to Microsoft or Face++—failed to recognize the faces of women of color, and have a statistically significant error rate in the recognition of brown skin tones.22 Buolamwini even raised her concerns about Amazon’s Rekognition and its inaccuracy in detecting women of color to CEO Jeff Bezos.23

Drones and other robotic devices are all embedded with these politics that are anything but neutral and objective. Their deployment in a host of social contexts where they are charged with predicting and reporting on human behavior raises important new questions about the degree to which we surrender aspects of our social organization to such devices. In the face of calls for abolition of the carceral state (prisons, jails, and surveillance systems like biometric monitors), robots are entering the marketplace of mass incarceration with much excitement and little trepidation. Indeed, the robotic prison guard is estimated to cost about $879,000, or 1 billion Korean won, apiece.24

Steep price tag notwithstanding, prison authorities are optimistic that, if effective, the robots will eventually result in a cutting of labor costs. With over 10.1 million people incarcerated worldwide, they see the implementation of robotic guards as the future of penal institution security. . . . For their part, the designers say that the next step would be to incorporate functionality capable of conducting body searches, though they admit that this is still a ways off—presumably to sighs of relief from prisoners.25

Predictive technologies are with us, particularly in decisions that affect policing, or insurance risk, or whether we are at risk for committing future crime, or whether we should be deported or allowed to emigrate. They are also part of the logic that can drive some types of robots, particularly those trained on vast data sets, in order to make decisions or engage in various behaviors. New robotics projects are being developed to outsource the labor of human decision-making, and they will open up a new dimension of how we will legally and socially interpret the decisions of robots that use all kinds of unregulated software applications, with little to no policy oversight, to animate their programmed behavior.

But My Robot Is for Social Good!

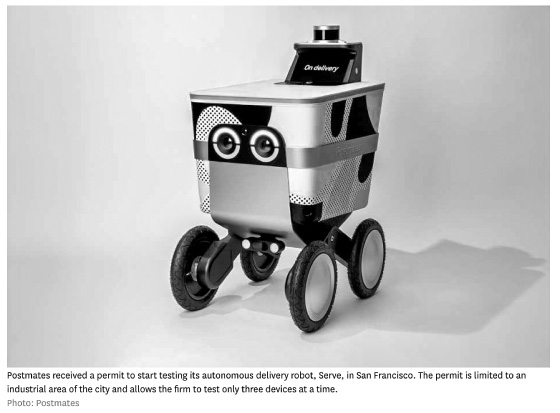

The prevailing thinking about robots is far less nefarious than drones using faulty facial-recognition systems before a military or police strike on various global publics. On a subsequent visit to Stanford University some months after the gathering of women roboticists and social scientists, I encountered a small robot on the street not unlike the newest food delivery robot, Steve, launched in August 2019 in San Francisco (see fig. 9.5).

The Postmates robot, Steve, requires a human operator—a reminder from the work of Sarah Roberts in this volume that “your AI is a human,” and in this case your robot is basically managed and manipulated by a human standing about thirty feet away.26 Steve and the media coverage about the glory of human partnerships with robots to reduce traffic, parking hassles, and time spent to get food a few feet out of the restaurant to the delivery driver are typical of the way robots are framed as helpful to our local economies. But the darker stories of how the entire enterprise of food delivery companies like Postmates, Grubhub, Uber Eats, and DoorDash are putting our favorite local restaurants out of business for the exorbitant fees they charge for their services are often hidden in favor of from mainstream media stories like the launch of Steve. Meanwhile, community activists are increasingly calling on the public to abandon these services at a time when we are being persuaded through cute little robots like Steve to look past the exploitive dimensions of the business practices of their tech company progenitors.27

Figure 9.5 “Steve” is Postmates’ autonomous food delivery robot. (Source: Postmates.)

Conclusion

The future of robotics, as it currently stands, may be the continuation of using socially constructed data to develop blunt artificial intelligence decision-making systems that are poised to eclipse nuanced human decision-making, particularly as it’s deployed in robotics. This means we must look much more closely at privatized projects in industry-funded robotics research and development labs, which are deployed on various publics. We have very little regulation about human–robotics interaction, as our legal and political regimes are woefully out of touch with the ways in which social relations will be transformed with the introduction of robotics we engage with at home and at work.

In 2014, Professor Ryan Calo issued a clarion call for the regulation of robots through a Federal Robotics Commission that would function like every other US consumer safety and protection commission.28 Four years later, on June 7, 2018, the MIT Technology Review hosted the EmTech Next conference, a gathering of people interested in the future of robotics. Most of the attendees hailed from the finance, education, government, and corporate sectors. According to reporting by Robotics Business Review, five key themes emerged from the conference: (1) to see “humans and robots working together, not replacing humans,” (2) to deal with the notion that “robots are needed in some markets to solve labor shortages,” (3) that “education will need to transform as humans move to learn new skills,” (4) that “lower skilled workers will face difficulty in retraining without help,” and (5) “teaching robots and AI to learn is still very difficult.”29 Not unlike most of the coverage for Robotics Business Review, the story represented the leading thinking within the commercial robotics industry: robots are part of the next chapter of humanity, and they are here to stay. Yet Calo’s concerns have largely gone unaddressed in the call for coordinated and well-developed public policy or oversight.

We have to ask what is lost, who is harmed, and what should be forgotten with the embrace of artificial intelligence and robotics in decision-making. We have a significant opportunity to transform the consciousness embedded in artificial intelligence and robotics, since it is in fact a product of our own collective creation.

Notes

1. This chapter is adapted from a short-form blog post at FotoMuseum. See Safiya Umoja Noble, “Robots, Race, and Gender,” Fotomuseum.com (January 30, 2018), https://www.fotomuseum.ch/en/explore/still-searching/articles/154485_robots_race_and_gender.

2. Donna J. Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s,” Australian Feminist Studies 2 (1987): 1–42.

3. Sherry Turkle, Life on the Screen (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

4. J. Robertson, “Gendering Humanoid Robots: Robo-Sexism in Japan,” Body & Society 16 (2010): 1–36.

5. Roger Andre Søraa, “Mechanical Genders: How Do Humans Gender Robots?,” Gender, Technology and Development 21 (2017): 1–2, 99–115, https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2017.1385320; Roger Andre Søraa, “Mecha-Media: How Are Androids, Cyborgs, and Robots Presented and Received through the Media?,” in Androids, Cyborgs, and Robots in Contemporary Culture and Society (Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2017).

6. See Sarah Mirk, “Popaganda: Fembots,” Bitch (December 7, 2017), https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/popaganda-fembots-westworld-female-robots-siri-ex-machina-her-metropolis-film.

7. Miriam Sweeney, “The Intersectional Interface,” in The Intersectional Internet: Race, Gender, Class & Culture, ed. Safiya Umoja Noble and Brendesha M. Tynes (New York: Peter Lang, 2016).

8. Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York: NYU Press, 2018).

9. Christopher Grau, “There Is No ‘I’ in ‘Robot’: Robots and Utilitarianism,” in Machine Ethics, ed. M. Anderson and S. L. Anderson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 451–463.

10. For a definition of the concept of “machine morality,” see John P. Sullins, “Introduction: Open Questions in Roboethics,” Philosophy & Technology 24 (2011): 233, http://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-011-0043-6.

11. Cathy O’Neil, Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (New York: Crown Publishing, 2016).

12. Kate Crawford and Jason Schultz, “Big Data and Due Process: Toward a Framework to Redress Predictive Privacy Harms,” Boston College Law Review 55, no. 93 (2014), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2325784.

13. Peter Smagorinsky, “The Social Construction of Data: Methodological Problems of Investigating Learning in the Zone of Proximal Development,” Review of Educational Research 65, no. 3 (1995): 191–212, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1170682.

14. Imanol Arrieta Ibarra, Leonard Goff, Diego Jiménez Hernánd, Jaron Lani, and E. Glen Weyl, “Should We Treat Data as Labor? Moving Beyond ‘Free,’” American Economic Association Papers & Proceedings 1, no. 1 (December 27, 2017), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3093683.

15. See letter from concerned faculty to LAPD, posted by Stop LAPD Spying on Medium (April 4, 2019), https://medium.com/@stoplapdspying/on-tuesday-april-2nd-2019-twenty-eight-professors-and-forty-graduate-students-of-university-of-8ed7da1a8655.

16. Andrew G. Ferguson, “Predictive Policing and Reasonable Suspicion,” Emory Law Journal 62, no. 2 (2012), http://law.emory.edu/elj/content/volume-62/issue-2/articles/predicting-policing-and-reasonable-suspicion.html.

17. Crawford and Shultz cite the following: Ferguson, “Predictive Policing” (explaining predictive policing models).

18. Crawford and Schultz, “Big Data and Due Process.”

19. Drew Harwell and Nick Miroff, “ICE Just Abandoned Its Dream of ‘Extreme Vetting’ Software That Could Predict Whether a Foreign Visitor Would Become a Terrorist,” Washington Post (May 17, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2018/05/17/ice-just-abandoned-its-dream-of-extreme-vetting-software-that-could-predict-whether-a-foreign-visitor-would-become-a-terrorist/?utm_term=.83f20265add1.

20. “An Open Letter to Microsoft: Drop your $19.4 million ICE tech contract,” petition, accessed July 29, 2018, https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/an-open-letter-to-microsoft-drop-your-194-million-ice-tech-contract.

21. See Kate Conger, “Google Plans Not to Renew Its Contract for Project Maven, a Controversial Pentagon Drone AI Imaging Program,” Gizmodo (June 1, 2018), https://gizmodo.com/google-plans-not-to-renew-its-contract-for-project-mave-1826488620.

22. Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, “Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification,” Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research 81 (2018): 77–91.

23. See Ali Breland, “MIT Researcher Warned Amazon of Bias in Facial Recognition Software,” The Hill (July 26, 2018), http://thehill.com/policy/technology/399085-mit-researcher-finds-bias-against-women-minorities-in-amazons-facial.

24. Lena Kim reported the robotic prison guards are developed by the Asian Forum for Corrections, the Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute, and manufacturer SMEC. See Lena Kim, “Meet South Korea’s New Robotic Prison Guards,” Digital Trends (April 21, 2012), https://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/meet-south-koreas-new-robotic-prison-guards/.

25. Kim, “Robotic Prison Guards.”

26. See story by Sophia Kunthara and Melia Russell, “Postmates Gets OK to Test Robot Deliveries in San Francisco,” San Francisco Chronicle (August 15, 2019), https://www.sfchronicle.com/business/article/Postmates-gets-OK-to-test-robot-deliveries-in-San-14305096.php.

27. See Joe Kukura, “How Meal Delivery Apps Are Killing Your Favorite Restaurants,” Broke-Ass Stuart (February 14, 2019), https://brokeassstuart.com/2019/02/14/how-meal-delivery-apps-are-killing-your-favorite-restaurants/.

28. Ryan Calo, “The Case for a Federal Robotics Commission,” Brookings Institution Center for Technology Innovation (September 2014), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2529151.

29. Keith Shaw, “Five Robotics and AI Takeaways from EmTechNext 2018,” Robotics Business Review (June 7, 2018), https://www.roboticsbusinessreview.com/news/5-robotics-and-ai-takeaways-from-emtechnext/.