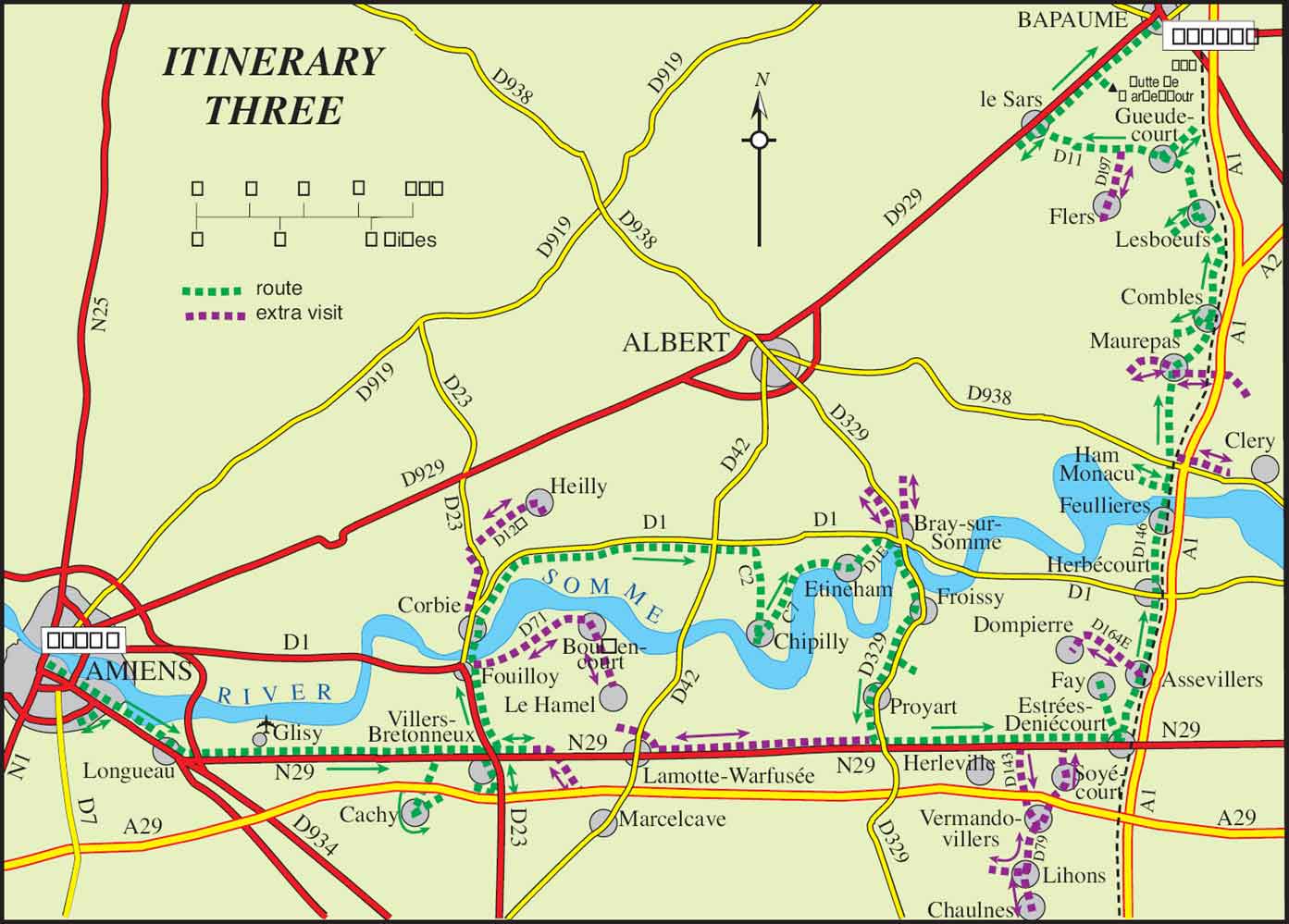

• Itinerary Three starts at Amiens Cathedral and heads east across the battlefields of 1918, via the Australian National Memorial at Villers Bretonneux. It continues east into the French sector of the 1916 fighting and then north behind the German second line to the Butte de Warlencourt and ends in Bapaume.

• The Route: Amiens – Cathedral, station area, French National Cemetery, St Acheul; Longueau railway; Longueau British CWGC Cemetery; Glisy Airport; the ‘Nearest Point to Amiens’; first Tank Versus Tank Battle; Adelaide CWGC Cemetery; Villers Bretonneux – Museum, school, Mairie, marker stone, Australian National Memorial and Interpretation Centre ; Corbie – Church Congreve Plaque, Communal Cemetery & Extension, Colette Statue; Von Richthofen Crash Site; Australian 3rd Div Memorial; Beacon CWGC Cemetery; 58th (London) Div Memorial; Chipilly CWGC Cemetery; Bray – Côte 80 French National Cemetery, German Cemetery; P’tit Train Terminus, Froissy; Proyart – miniature Arc de Triomphe, German Cemetery; Col Rabier Private Memorial; Foucaucourt Local Cem; Estrées - Lt Col Puntous Memorial; Assevillers New CWGC Cemetery; Hem Farm CWGC Cemetery; ‘HR’ Private Memorial; Maurepas 1st RI Memorial; V. Hallard Private Memorial; Charles Dansette Private Memorial; Maurepas – French National Cemetery, Memorial; Combles – Communal Cemetery Extension, Guards Cemetery; Guards Memorial, Lesboeufs; Capt Meakin Private Memorial; Gueudecourt Newfoundland Memorial; AIF Grass Lane CWGC Cemetery; SOA Lt Col R. B. Bradford VC; German Memorial, Le Sars; Butte de Warlencourt, WFA & other Memorials; Warlencourt CWGC Cemetery; Bapaume.

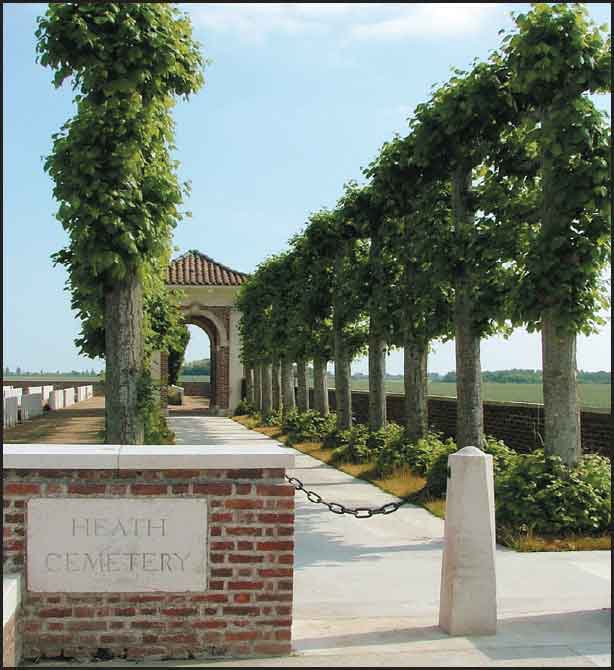

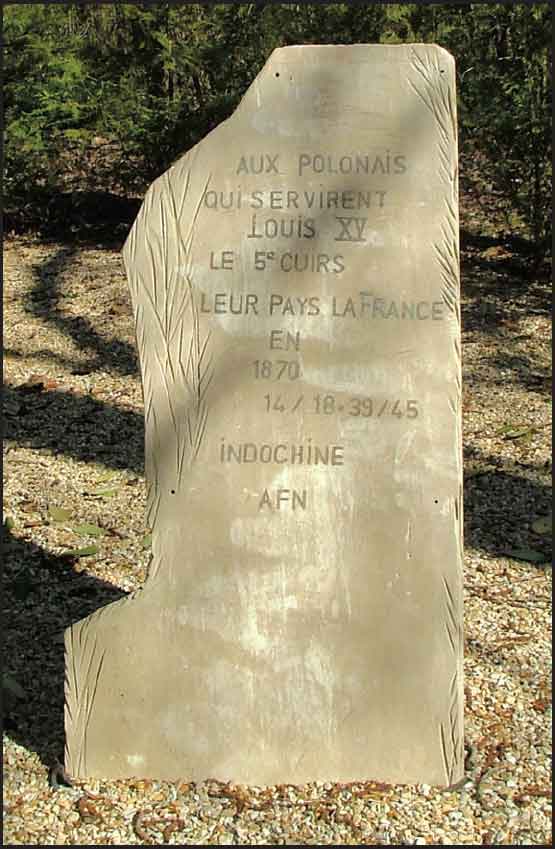

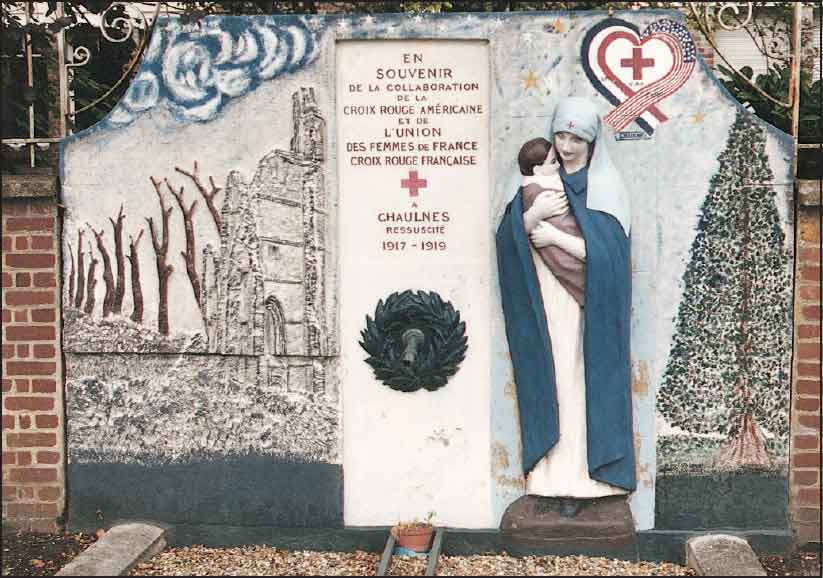

• Extra Visits are suggested to: Marcelcave French National Cemetery; Vaire Com Cemetery; Capt Mond/Lt Martyn Private Memorial; Le Hamel Australian Memorial Park/RB Plaque; Heilly Station CWGC Cemetery, Private Memorial to L Cpl O’Neill;, Bray-French National Cemetery, Grove Town, Bray Military, Bray Vale and Bray Hill CWGC Cemeteries; Site of Carey’s Force Action; Heath CWGC Cemetery; Ruined Village of Fay and Memorial Plaques; Vermandovillers - German Cemetery, RB Plaque Lt McCarthy VC, Capt Delcroix, Bourget & 158th RI, 1st Chass à Pied; Lihons - French National Cemetery, Polish Memorial, Murat Monument; Chaulnes – US & French Nurses, Ger 16th Bav Memorial; German Trenches, Bois de Wallieux; Fay – Ruined Village, Memorials to Capt Fontan, Abbé Champin & 41st RI 1940; French National Cemetery & Italian Memorial, Dompierre; Cléry - French National Cemetery/383rd RI Memorial; Gaston Chomet Private Memorial; Heumann/Mills/Torrance Private Memorial; 41st Div Memorial; Bull’s Road CWGC Cemetery; French 17th/18th RIT Memorial; Achiet-le-Grand Comm Cem + Ext, Memorials to Pte C. Cox, VC and Lt Wainwright, RND, Loupart Wood.

[N.B.] The following sites are indicated:

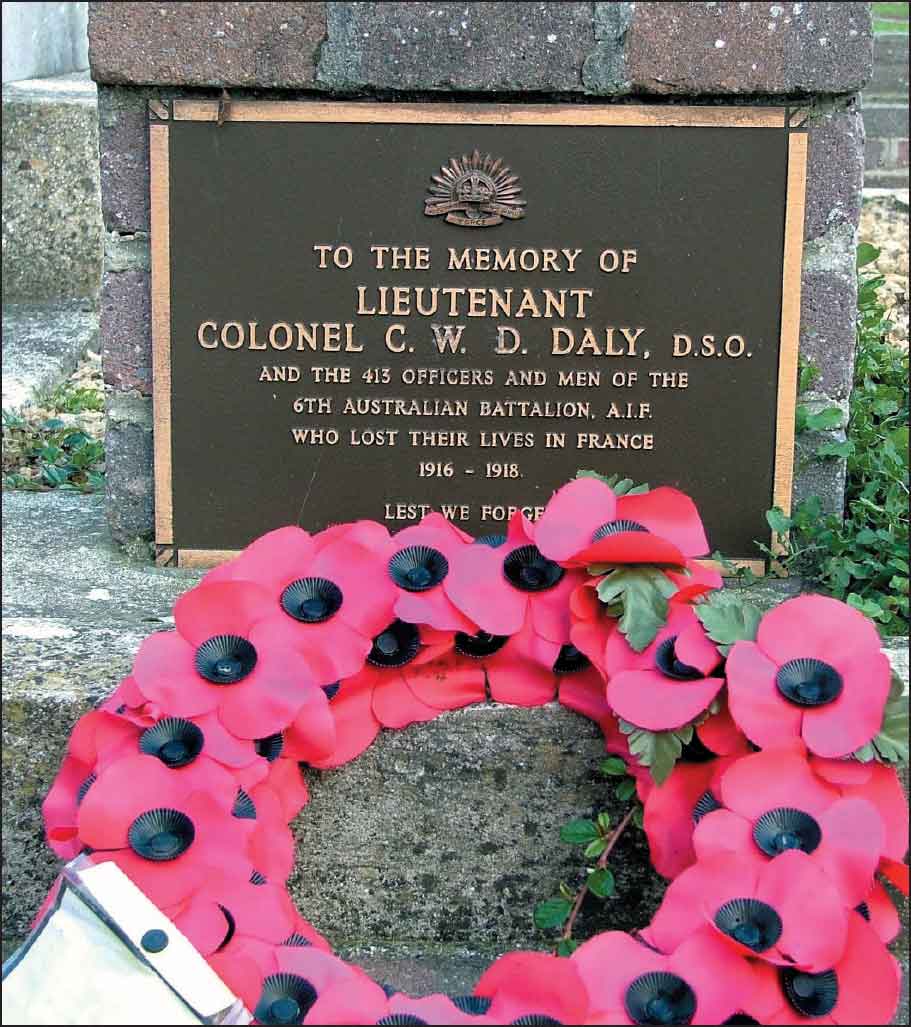

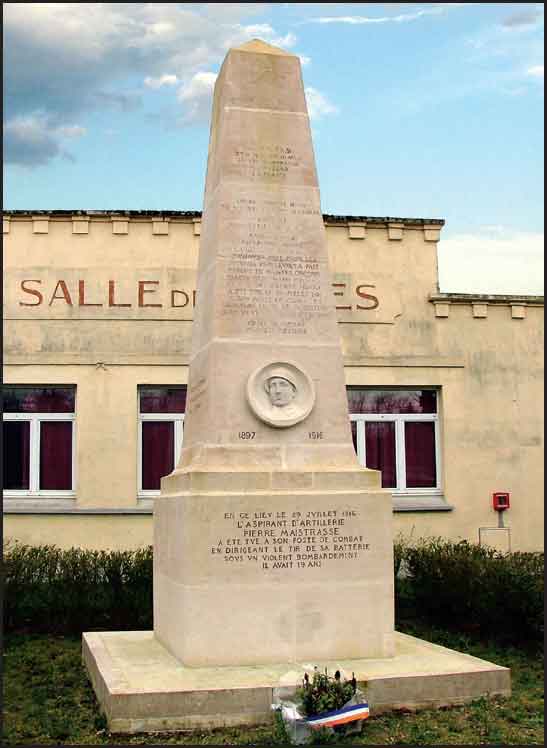

Herleville – Plaque to Lt-Col Daly & 6th AIF; Logeast Wood - SOA T/Cdr Daniel Marcus Beak, VC; Courcelles le Comte – Mem to Pte Hugh McIver, VC, MM + Bar; Foucaucourt - French Cemetery; Herbécourt – Private Mem to Aspirant P. Maistrasse.

• Planned duration, without stops for refreshment or extra visits: 8 hours 45 minutes.

NOTE. This a long itinerary! You may want to split it into two and a convenient place to break it would be before Assevillers New Brit Cem on page 245

• Amiens/ 0 miles/RWC/Map 1/6

Follow the brown signs Parking Jacobin, which is centrally placed and well signed from main roads into the city, and park. Set your milometer to Zero. Note that the time spent in this walk is not included in the overall timing of the Itinerary.

Walk following signs to the Cathedral. En route we advise visiting:

Amiens Métropole Tourist Office (GPS: 49.894579 2.301614).

This is in Place Notre Dame, The Cathedral Square. Tel: +(0)3 22 71 60 50 E-mail: ot@amiens-metropole.com. Website: www.amiens-tourisme.com

Over the past few years the centre of Amiens has undergone a major ‘facelift’, with many of the old façades, monuments and public buildings cleaned and renovated and plenty of pleasant pedestrian shopping areas. It makes an ideal base for touring the battlefield if you follow The Western Approach. This attractive city has just about every category of Hotel and a variety of Restaurants in the Centre and in the suburbs and here you can pick up helpful literature about these, restaurants and camping etc and local events. See also the Tourist Information section at the end of the book.

Open daily: 1 April-30 Sept 0830-1815, 1 Oct-31 March 0830-1715. There is an entrance fee for guided visits. Autoguide in 3 languages €3.

On 28 August the Germans took Péronne and the citizens of Amiens trembled as the enemy fought their way towards the city, then occupied by Moroccan troops who were sent to take up defensive positions at Villers Bretonneux. A fierce fight was put up at Proyart, but the Germans counter-attacked and swept their way into Amiens on 31 August 1914, and, as recorded in a notice posted by the Mayor, M. Fiquet, seized twelve hostages from the town council, who, unlike German hostages taken in other towns, such as Senlis, were unharmed. They requisitioned half a million francs worth of supplies to sustain them on their drive towards Paris. Most of the force, after pulling down the French tricolore and hoisting the German flag on the town hall and raiding the safes in the savings bank, proceeded on their way ‘nach Paris’, but a garrison was installed with a town major on 9 September. A curfew was imposed, motor cars were requisitioned and 1,000 young men were sent into captivity. Following their defeat on the Marne, the Germans withdrew, and on 12 September the French Army, under General D’Amade, returned.

Although damaged by air attacks during the next 3½ years, it was not until the German offensive of 1918 that the city again came under a major attack. From April to June it endured an almost continuous artillery bombardment, most citizens were evacuated and the Pope was asked by the Bishop to intercede with Kaiser Wilhelm to save the cathedral from the shelling. The Germans did not reach Amiens. They were stopped at Villers Bretonneux (see below). On 17 November 1918 a Mass of Thanksgiving was held here to celebrate the end of the war.

Designed by Robert de Luzarches, the Cathédrale de Notre Dame was begun in 1220 as a suitable resting place for the relic brought back from the Fourth Crusade by Walon of Sarton – the forehead and upper jaw of John the Baptist. It also houses relics of Saint Firmin, the first Bishop of Amiens. The cathedral is regarded as one of the finest and most harmonious examples of Gothic architecture and, at 142m long and 42m high, has the greatest volume. Ruskin called it ‘the Bible of Amiens’ as its stone façade and wooden choir stall contain so many carved pictures of Bible stories. Edward III attended mass in the cathedral on his way to the Battle of Crécy and Pte Frank Richards DCM, MM of the 2nd Bn, RWF, author of Old Soldiers Never Die, visited it in August 1914. Richards was ‘very much taken up with the beautiful oil paintings and other objects of art inside. One old soldier who paid it a visit’, he reported, however, ‘said it would be a fine place to loot’. A huge restoration and cleaning project was started in 1994.

During World War I elaborate precautions were taken to protect the cathedral and its priceless art treasures – all portable items (including the stained glass, which was taken by firemen from Paris) being removed for safekeeping. The choir stalls were enclosed with reinforced concrete and sandbags (a precaution that was to be repeated in World War II), as was the principal façade. Although it received nine direct hits by bombs and some shells, none caused serious damage. During the Spring 1918 offensive, when the Germans reached Villers-Bretonneux and Amiens came under such fearsome bombardment that over 2,000 houses were hit and all the inhabitants fled, the British war correspondent Philip Gibbs described it under the moonlight, ‘… every pinnacle and bit of tracery shining like quicksilver, with magical beauty’.

It contains the standard CWGC Memorial Plaque, twenty-eight of which were designed for erection in cathedrals and important churches in Belgium and France by Lt Col H.P. Cart de Lafontaine, FRIBA and made by Hallward. The inscription was written by Rudyard Kipling. The Amiens Plaque was the first to be unveiled (by the Prince of Wales, then President of the CWGC) in July 1923. It is slightly different from the others, as it bears the Royal Coat of Arms alone and commemorates the war dead of Great Britain and Ireland who were killed in the diocese. The Plaques in other churches also bear the coats of arms of the Dominions. In Amiens there are separate Plaques for Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand, South Africa and the USA. A replica of the Amiens Plaque is in the reception area of the CWGC headquarters in Maidenhead, and a similar Plaque is in Westminster Abbey. There is a Private Memorial to Lt Raymond Asquith (see Itinerary Two). There is also a Plaque to General Debeney, ‘Vainqueur de la Bataille de Picardie’, who liberated Montdidier on 8 August 1918.

Amiens Cathedral plaques: CWGC (left), US 6th Engineers, Carey’s Force (right)

Nearby are the ****Hotel Mercure Amiens Cathédrale, 21/23 rue Flatters, Tel: +(0)3 22 80 60 60, e-mail: h7076@accor.com and the ***Ibis Styles Amiens Cathédrale, 17-19 Place au Feurre, +(0)3 22 22 00 20, e-mail: h04780@accor-hotels.com. No restaurant but complimentary breakfast and tea/coffee.

Over the River Somme beyond the Cathedral is the picturesque old town of St Leu with some charming Cafés and Restaurants. Boats depart from the quay here for trips on the river, along which hospital barges plied from the battlefields, and the unique Hortillonages (see Tourist Information).

Return to your car, drive out of the car park and turn right along rue des Jacobins. Turn right following signs to SVCF Gare along rue des Otages to just short of the Station.

• Amiens Station/Carlton-Belfort Hotel/0.5 miles/GPS:49.89054 2.30804

The square in front of the station, now covered by a magnificent canopy, and with a car park underground, is the Place Alphonse Fiquet (named after the Mayor of Amiens in August 1914). The station and the 104m, twenty-six-floor-high tower opposite were both designed by August Perret. He gave his name to the Tower, which was once the tallest office building in the western hemisphere and still makes an excellent landmark. A residential block, the Tower is now surmounted by a 7metre high glass cube which is lit up at night, but is not yet open to visitors. The Station Restaurant was once renowned for its gourmet cuisine and the Prince of Wales lunched there after inaugurating the Thiépval Memorial on 31 July 1923. No stranger to Amiens, the young Grenadier Guards Officer had frequently dined in Amiens’ popular restaurants when he had been in the Somme area during 1916. When the Prince himself could not get away, Raymond Asquith borrowed … “Wales’ excellent Daimler” and whipped off to Amiens where he “ate and drank a great deal of the best, slept in downy beds, bathed in hot perfumed water, and had a certain amount of restrained fun with the very much once-occupied ladies of the town.”

The Carlton Hotel, Amiens.

On the corner opposite the station is The ***Hotel Carlton, Tel: +(0)3 22 97 72 22, e-mail: reservation@lecarlton.fr, excellent Brasserie) on the opposite left corner, once the famous Carlton-Belfort Hotel whose façade had altered little since 1918 until a change of ownership and a facelift in the late 1980s. Up to then a wartime sign, ‘No Lorries Through Town’ could still be discerned on the wall to the right of the main entrance on rue de Noyon. Apart from the wartime industrial activity which thrived in the city, its function as staff HQ’s and its many temporary hospitals, Amiens was known chiefly as a place of relaxation for the Allied soldiers. Among notables who visited (and wrote about) the Carlton-Belfort were Siegfried Sassoon, Edwin Campion Vaughan, Robert Graves, Cecil Lewis, and Mick Mannock. Many famous war correspondents and artists were based at or visited Amiens, and other popular haunts were the Hôtel du Rhin (now no longer a hotel but the building may be seen by continuing down the rue de Noyon and turning left when you reach the Place René Goblet, with its World War II memorials to the Martyrs of Picardy and to General Leclerc). A regular patron of the Hôtel du Rhin in the days leading up to ‘The Big Push’ in 1916 was the cartoonist Bruce Bairnsfather, who was based at the administrative HQ at Montrelet as a lowly Staff Officer. The very name, he wrote, ‘at once conveys visions to [one’s] feverish mind of the gladdest nights that were then permissible’. John Masefield, commuting between Amiens and Albert while researching for his book on the Somme, ‘dined on duck at the Rhin’ at a dinner given by Nevill Lytton for the US Ambassador, Gen Bliss the US CGS and Calvin Coolidge, the future President.

Sir William Orpen, KBE, RA, describes, in his book An Onlooker in France 1917-19, how he dined at the Rhin with the Canadian General Seely and Prince Antoine de Bourbon, Seely’s ADC. Orpen did a portrait of Seely while his friend, Alfred Munnings, who was official artist to the Canadian Cavalry Brigade, was painting an equestrian portrait of the prince. Philip Gibbs and other foreign correspondents found refuge there on the night when Amiens was under its greatest threat in April 1918. Bombs crashed around the hotel and the guests, who had voted whether to ‘Stay or Go’, stayed, but spent the night ‘in the good cellars below the Hôtel du Rhin, full of wine casks and crates’. Outside raged ‘a roaring furnace’. The Restaurant Godbert (62 Rue des Jacobins, but no longer a restaurant) was a favoured restaurant – ‘The food was excellent and we all had money to burn’, wrote Dennis Wheatley. But when he visited it on 1 April he found it rather like the Marie Celeste. It had closed suddenly when Amiens was being threatened and the Provost Marshal rounded up officers in all the main restaurants and ordered them back to their units at once. ‘Every table in the big restaurant had been occupied and on all of them were plates with half-eaten courses. On some there were only hors d’oeuvres, on others pieces of omelette, fish, game, savouries and ice-cream that had melted. Beside the plates stood glasses mostly full or half-full of red or white wine.’ Perhaps the Godbert’s popularity had something to do with ‘little Marguerite, [who] made eyes at all the pretty boys who craved for a kiss after the lousy trenches’. The poet, Capt T. P. Cameron Wilson of the Sherwood Foresters (commemorated on the Arras Memorial, qv), recalls the therapeutic effect of other waitresses with affection, including ‘Yvonne, bringing sticky buns’, in his delightful Song of Amiens:

Lord! How we laughed in Amiens!

For there were useless things to buy …

And still we laughed in Amiens,

As dead men laughed a week ago.

What cared we if in Delville Wood

The splintered trees saw hell below?

We cared … We cared … But laughter runs

The cleanest stream a man may know

To rinse him from the taint of guns’.

Bairnsfather cartoon, ‘A hopeless dawn. Just back off leave. Amiens is only 34 hours more in the train now. You know that because you can see the cathedral quite clearly.’

Some encounters with the female population of Amiens were not so innocent. When most civilians evacuated in March 1918, a few enterprising girls remained. Wheatley found one such after his disappointment at the Godbert who had remained on duty ‘Because I makes much money now there are few girls here’. It was not his first encounter with the oldest profession and he thoroughly recommended the dignified Madame Prudhomme’s brothel. Such delights had been available in Amiens from the outbreak of war. Private Frank Richards had passed through the city on 13 August 1914 on his way to Mons. At that time General French was staying at the Hôtel Moderne (of which no trace remains) and Richards was billeted in a school, outside which was a fifty-deep queue of young ladies waiting to entertain the soldiers. Richards was ‘sorry to leave’ on 22 August. ‘About the 16th August’, he reports, he had ‘attended a funeral of two of our airmen who had crashed; all the notabilities of the town were present.’ This was the funeral of Lt Perry and AM Parfitt, who are buried in St Acheul Cemetery (see below). He also describes the bringing of Gen Grierson’s body from the railway station to the Town Hall. He was Chief-of-Staff to General French. ‘All sorts of stories were going around regarding his death. One was that he had been poisoned when eating his lunch on the train, but I believe now it was just heart failure from the strain and excitement. We took his body back to the railway station where a detachment of Cameron Highlanders took it down-country.’ Lt-General Sir James Grierson, who was actually commander of II Corps, was buried in his home town of Glasgow.

The 64-year-old French Academician and novelist, Pierre Loti (the nom de plume of Louis Marie Julien Viaud), who had served with the French navy and who was put on the Reserve List in 1910, at the outbreak of war offered his services to General Galliéni as a liaison officer. On 2 October he recorded his ‘first day of service as a liaison officer’ in his diary and travelled through the early battlefields left by the Germans’ rush for Paris. He lunched in Amiens before visiting GHQ at Doullens and returned there that night. He found the town criss-crossed with parades of soldiers, singing, holding flowers that the young girls had given them. He did not return to the area until 1917 (when he again visited Amiens) – after tireless negotiations with the Turks, the Belgians, in Alsace, in Salonika and many parts of the French line, during which work he kept up a prodigious writing output. This indefatigable patriot was eventually forced to retire, exhausted, at the age of 68 on 1 June 1918. Another famous French writer, Jean Cocteau, stayed at the Hôtel du Commerce (32 rue des Jacobins) while waiting to be posted to his hospital near Villers Bretonneux in June 1916 (qv). On the 25th of that month, the Fourth Army Commander took time off from his planning of the Big Push to attend the 167-strong annual Old Etonian Dinner in Amiens.

Return to your car. Continue. Turn right with the station on your left, onto the D1029 direction Longueau. Continue to the large school, Lycée Robert de Luzarches on the left and immediately turn right on the Boulevard de Pont Noyelles, which becomes Boulevard de Bapaume. Ignore the first sign to the left to the Cimetières de St Acheul and take the next left on Rue de Cottency. Continue to the cemetery and stop at the entrance on the left.

• French National Cemetery, St Acheul, Graves of Perry & Parfitt/ 2.0 miles/10 minutes/Map 1/7/GPS: 49.87799 2.31624

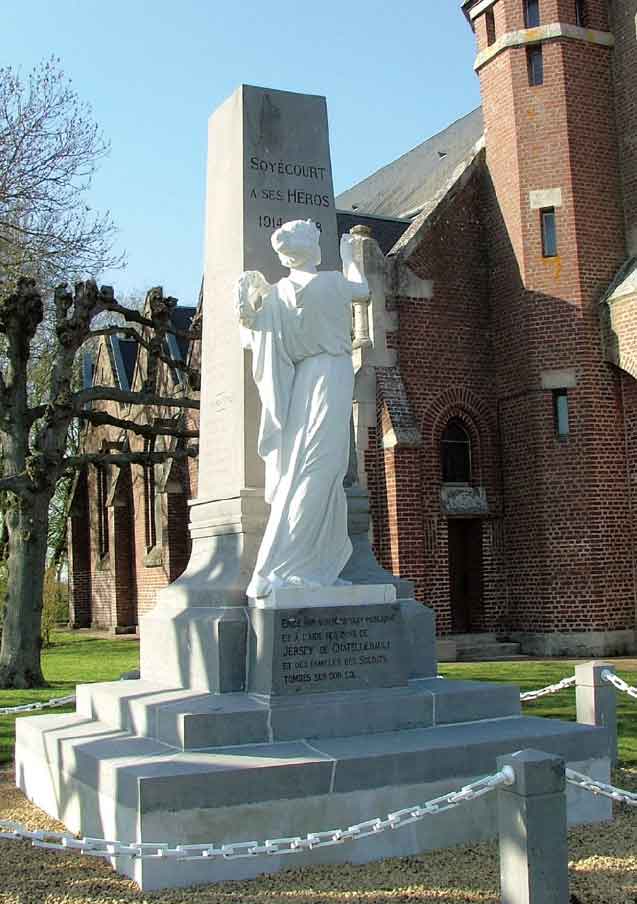

There is an Information Board (in French) just inside the entrance. In this French Cemetery, with its impressive memorial incorporating a sensitive sculpture of a mourning female figure, there are 2,739 French, 12 British, 10 Belgian and I Russian soldiers of World War I. The British plot, just inside the entrance and to the left, includes the graves of the first airmen to be killed on French soil – on 16 August 1914. They are 2nd Lt Evelyn W. Copland Perry, RFC, age 23, the personal message on whose headstone reads, ‘First on the roll of honour. All Glory to his name’ and Air Mechanic H. E. Parfitt, age 21, the crew of a Royal Aircraft Factory BE8. Perry was the last of his Squadron (3 Sqn) to take off from Amiens airport at Glisy en route for Mons, when his machine stalled, plummeted to earth and burst into flames. Other contenders for ‘first casualties’ were Lt C. G. G. Bayly and 2nd Lt V. Waterfall of 5 Squadron RFC. They were killed on 22 August, six days later than Perry and Parfitt, but they were actually killed as a result of enemy action on a reconnaissance flight over Mons. They are buried in Tournai Communal Cemetery.

Return to the D1029 and turn right signed Longueau. Pass under a railway bridge, over a waterway which marks the junction of the Rivers Avre, Noye and Somme and then across a bridge over a large railway complex.

Headstones of 2nd Lt E.W.C. Perry and Air Mech H.E. Parfitt, St Acheul French Cemetery

• Longueau/4 miles

This area became a major administrative centre, supplying the Somme battlefront and it was from it that railway engineers worked eastwards to repair the railways destroyed during the 1914 German advance and subsequent shelling.

Continue uphill on the D1029, passing the Hôtel de Ville of Longeau on the right, to a cemetery on the right by traffic lights at the junction of Rue des Alliés.

• Longueau British CWGC Cemetery/4.9 miles/5 minutes/Map 1/8a/GPS: 49.86969 2.35986

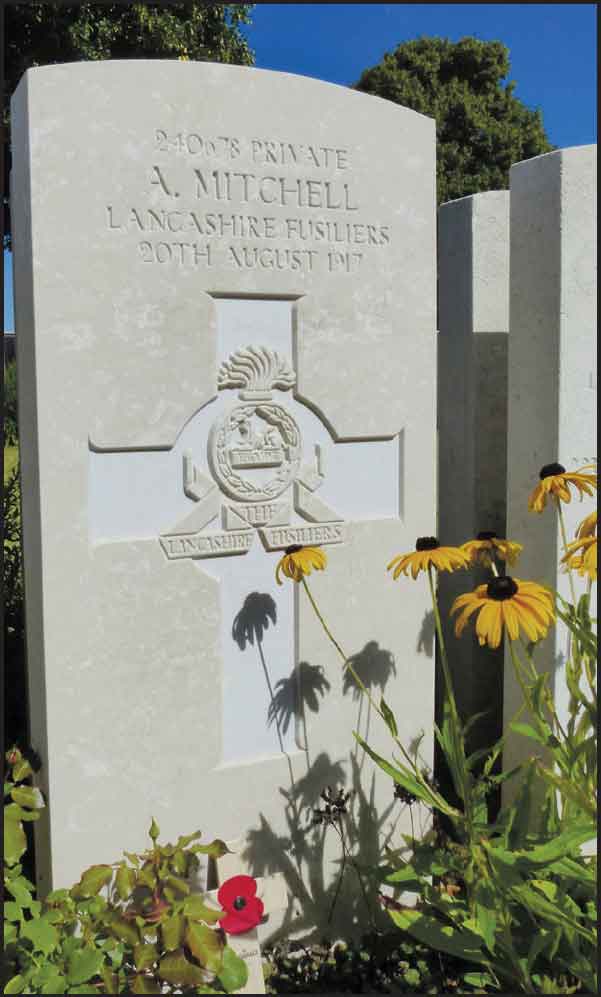

Unusually, the register box is incorporated at the bottom of the Cross of Sacrifice in this small Cemetery. It was begun in April 1918 when the British line was re-established before Amiens and used by fighting units and field ambulances until the following August. Plot IV was made after the Armistice by concentrating thirty-six graves from other cemeteries and the surrounding battlefield. Three US, one French and thirty-nine German graves have been removed. Now there are 68 soldiers, and airmen from the UK, 66 from Canada, 65 from Australia, 3 from the West Indies including 1 unidentified, and 14 unknown. Two graves were moved here as late as 1934.

Continue straight through a series of roundabouts (don’t turn right following Autoroute signs) and follow signs to Villers Bretonneux/Péronne on the D1029.

You will pass near the group of hotels which includes the ****Novotel Hotel, ***Campanile and several other hotels at this point (see Tourist Information).

Continue on the D1029 to the airfield on the left.

• Glisy Airport/6.0 miles/Map 1/8/GPS: 49.86830 2.391212

The area was used by the RFC/RAF as an airfield from the first days of the war and is currently both a commercial and club field. In the early 1980s a new bar complex was built and a Memorial to the Red Baron (originally destined to be erected at his crash site (qv) but rejected by local authorities) which used to stand in the old bar, went missing and is now thought to be in the hands of an Amiens collector. During the fighting of March 1918, General Sir John Monash, who commanded the Australian 3rd Division that played such a large part in the fighting up ahead at Villers Bretonneux, had his HQ in this vicinity. Maurice Baring, in Flying Corps HQ, 1914-1918, describes arriving at Amiens by train on 12 August where he was greeted with the scornful statement, ‘Ah! les aviateurs, ils n’ont pas besoin d’aller à la guerre pour se faire casser la gueule ceux-là.’ (‘Oh! airmen – that lot don’t need to go to war to break their necks.’). ‘After lunch’ he went to the ‘Aerodrome’ and arranged supplies of ‘water carts, … pegs for the aeroplanes, … a certain consignment of B.B. Oil’, and then ‘slept on our valises on the grass on the Aerodrome.’ On the morning of the 13th, the first three squadrons of the RFC’s total complement of four squadrons arrived, Harvey-Kelly (see also Vert Galand on page 61) being the first to land in his BE2A. They had taken off from a field above the White Cliffs of Dover, on the road to St Margaret’s Bay. Today a Memorial stands at the entrance to that field, with the inscription, ‘The Royal Flying Corps contingent of the 1914 British Expeditionary Force, consisting of Nos 2, 3, 4 and 5 Squadrons flew from this field to Amiens between 13 and 15 August 1914.’ In the afternoon Prince Murat (qv) reported as their Liaison Officer and on 14 August Sir John French arrived to look at the squadrons. The airfield was also used during World War II.

To commemorate the WW1 Centenary, an important airshow was held here in 2014.

Continue (noting that the road runs due east), crossing the railway twice in the next 5 miles.

Note the tall column of the Australian Memorial which becomes more and more clearly visible to the left along this road.

Continue downhill past a wood on the right to a small crossroads with the D523. Turn right and stop as near to the crossing as practical.

• The Nearest Point to Amiens/10.8 miles/5 minutes/OP/GPS: 49.86974 2.49029

The German attack on 21 March 1918 forced the British and French armies into a hurried retreat, troops pouring towards you on their way back to Amiens. Up ahead of you on the crest is the village of Villers Bretonneux and it was not until 28 March that the German advance (which had begun some 50km away at St Quentin) was stopped 3km east of the village – i.e. the other side to where you are now – mainly due to the efforts of the 1st Cavalry Division. Short of troops, and with Amiens in great danger, Haig looked 100km north to Flanders and ordered down the Australians. Thirty-six hours after the German onslaught began again at dawn on 4 April it seemed as if Villers Bretonneux would be taken, but Lt Col H. Goddard commanding the 9th (Australian) Brigade, newly based in the town, ordered the 36th Battalion forward in a bayonet charge. The advancing Germans broke and withdrew and, before they could attack again, one of their aerial heroes, the ‘Red Baron’ (qv) was killed.

By 10 April, Haig knew the situation was critical and he begged Foch to take over some portion – any portion – of the front held by British and Commonwealth forces, stretched to the point of exhaustion. Foch agreed to move up a large French force towards Amiens. The next day (12 April), still waiting for them to arrive, a worried Haig issued his famous ‘Order of the Day’:

“To all Ranks of the British Forces in France. Three weeks ago today the Enemy began his terrific attacks against us on a 50 mile front …. Many amongst us are tired …. There is no other course open to us but to fight it out! Every position must be held to the last man: there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall, and believing in the justice of our cause, each one of us must fight to the end….”

In the dawn mist of 24 April the German 4th (Guards) Division and the 228th Division, supported by thirteen tanks, tried again. It was to be one of the first actions in which the Germans had used tanks and the first action in which tank fought tank.

This time the enemy got into and through the village, despite the determined resistance by 2nd West Yorkshire Regiment at the railway station, so that by 2000 hours that evening the front line ran at right angles to the D1029 along the D523 (where you now are) across your front to your left and right. It was the nearest point to Amiens that the Germans reached. That evening at 2200 hours the Australian 13th Brigade counterattacked in the area on the right but was caught in fierce fire by German machine guns of 4th (Guards) Division set up in the wood to your right – Abbey Wood.

In a remarkable action which won him the VC, Lt C. W. K. Sadlier led a small party into the wood and destroyed six machine-gun positions, thus allowing the attack to continue. An hour later the Australian 15th Brigade, in the light of flames from the burning château in the village, attacked in a pincer movement through the area beyond the railway line to your left. After the war Sadlier played an important role in the Returned Services League.

Continue on the D523 towards Cachy.

In springtime the banks and woods here are carpeted with celandine and cowslips.

Immediately before the motorway bridge turn sharp left towards Villers Bretonneux.

Continue and pull in and stop just before the de-restriction 70 sign on the right with Villers Bretonneux church on the skyline ahead.

• First Tank versus Tank Battle Monument, Cachy/12.2 miles/10 minutes/Map 1/14/GPS: 49.86060 2.49667

Stop here before visiting the memorial to read the following account and to see where the action took place.

The historic tank versus tank action took place in the fields to your left and to your right on the slope up towards Villers Bretonneux on the morning of 24 April 1918. At 0345 hours German artillery began an HE and gas shell barrage on British positions in the town and on the feature on which the Australian National Memorial now sits. The attack began at 0600 hours and, led by thirteen A7V tanks, the Germans inflicted heavy casualties on the East Lancashires of 8th Division in the area around the railway station. By 0930 four A7Vs were making their way across the fields towards where you now are. Earlier that morning three British Mark IV tanks, lagered in the wood through which you drove from the D1029, were ordered to move to this area forward of Cachy. They too were moving this way at about 0930. Commanding one of the British tanks was Lt Frank Mitchell and in his book, Tank Warfare, he told what happened:

“Opening a loophole I looked out. There, some three hundred yards away, a round squat-looking monster was advancing, behind it came waves of infantry, and farther away to the left and right crawled two more of these armed tortoises …. So we had met our rivals at last. Suddenly a hurricane of hail pattered against our steel wall, filling the interior with myriads of sparks and flying splinters … the Jerry tank had treated us to a broadside of armour-piercing bullets … then came our first casualty … the rear Lewis gunner was wounded in both legs by an armour-piercing bullet which tore through our steel plate … the roar of our engine, the nerve-wracking rat-tat-tat of our machine guns blazing at the Bosche infantry and the thunderous boom of the 6 pounders all bottled up in that narrow space filled our ears with tumult while the fumes of petrol and cordite half stifled us.”

Mitchell’s tank attempted two shots at one of the A7Vs. Both hit but seemed ineffective, then the gunner tried again ‘with great deliberation and hit for the third time. Through a loophole I saw the tank heel over to one side then a door opened and out ran the crew. We had knocked the monster out.’

When the war was over, Mitchell, tongue in cheek, recalling that the tanks were called ‘landships’, and that naval crews are entitled to prize money for sinking enemy ships, applied for prize money for himself and his crew for having knocked out an enemy ‘landship’. The War Office descended into a puzzled silence and then turned the application down.

Before the day was over seven of the new British Whippet tanks charged into the German infantry and the advance stopped. The Germans, however, were now poised on the high ground. If Amiens were to be saved they had to be moved.

Just after dawn on 25 April the two attacking Australian brigades met on the other side of the town, taking almost 1,000 prisoners. It was ANZAC Day and Amiens was safe. After the action the Australians recovered one of two German tanks that had broken down and shipped it to Brisbane as a souvenir. The village was almost obliterated by the fighting and so great was the destruction that a sign was put up in the ruins proclaiming, ‘This was Villers-Bretonneux’.

Walk to the bottom of the hill – it is dangerous to park by the Memorial.

Tank versus Tank Memorial, Cachy

On the left is the small Memorial to the Tank Action with a caption in three languages, English, French and German, stating that ‘Here on 24 April 1918 the first ever tank battle took place between German and British armour.’

Return to your car, turn round, return to the D1029, turn right and continue to the CWGC Cemetery on the left.

• Adelaide Cemetery/14 miles/10 minutes/Map 1/13a/ABT3/GPS: 49.87024 2.49791

Note: ‘Australian Battlefield Tour (ABT) Point 3’ – from Villers Bretonneux a numbered ‘Australian’ tour may be followed using a route described in a commemorative pack issued by the Office of Australian War Graves and available at Villers Bretonneux Museum.

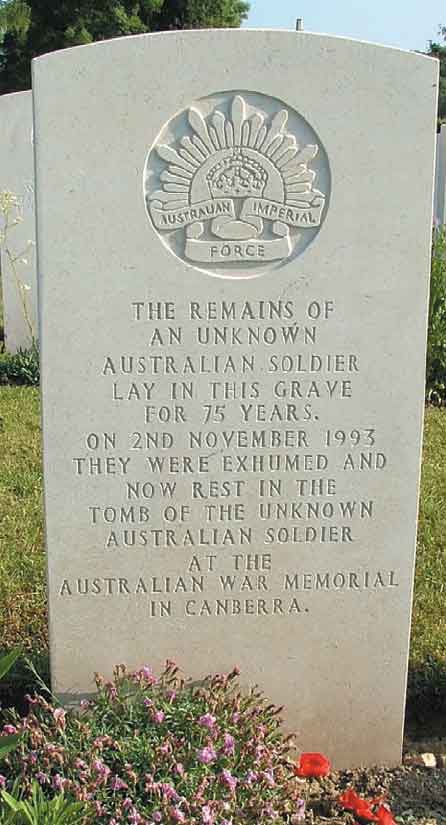

The cemetery, which has the most delightful and varied array of plants, was started in early June 1918 and used by 2nd and 3rd Australian Divisions. By the Armistice it contained ninety graves and then 864 other graves were concentrated here. There are now over 500 Australians, 365 soldiers and airmen from the UK, including Lt Col S. G. Latham, DSO, MC and Bar, age 46, killed on 24 April while commanding the 2nd Battalion the Northampton Regiment, and 22 Canadians. The 113th Australian Infantry Brigade, the 49th, 50th, 51st and 52nd Australian Infantry Battalions and the 22nd DLI all at one time erected wooden crosses here to commemorate their dead in the actions of Villers Bretonneux. In Plot III, Row M, Grave 13 is a most unusual headstone. It records the fact that ‘The remains of an Unknown Soldier lay in this grave for 75 years. On 2 November 1993 they were exhumed and now rest in the Tomb of the Unknown Australian Soldier at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.’

Continue, again crossing the railway, and 800m later there is on the left a

Original grave of the Australian Unknown Soldier, Adelaide CWGC Cem

• Memorial to the Villers Bretonneux Déportés of WW2/14.6 miles/GPS: 49.87059 2.51192.

It is in front of the Site of the Villers Bretonneux Château whose flames lit up the attack of the Australian 15th Brigade on the night of 24 April. After the War it was used as the HQ of the Australian Graves Registration Unit. Local opinion has it that after the war the owner of the château collected a considerable sum of money in reparations and decided to spend it elsewhere. When Henry Williamson returned to the Somme in 1929, he met in an estaminet in Albert the ‘son of a millionaire, who had made his “pile” since the war by buying for “cash down” the sites of shattered buildings, and rebuilding with the generous reparation grants later on’. The speculator himself then owned over fifty houses, shops, and three motor cars.

The ruins of the château were demolished in November 2004 as they were deemed to be dangerous. A housing estate has now been built on the site.

Continue some 300m to the crossroads with the D23 signed left to the Australian Villers Bretonneux Memorial. Turn right along the rue Maurice Seigneurgens. Turn right at the first crossroads along rue Driot to the next crossroads. Go straight over. The road is now called rue Victoria. Stop at the school on the left.

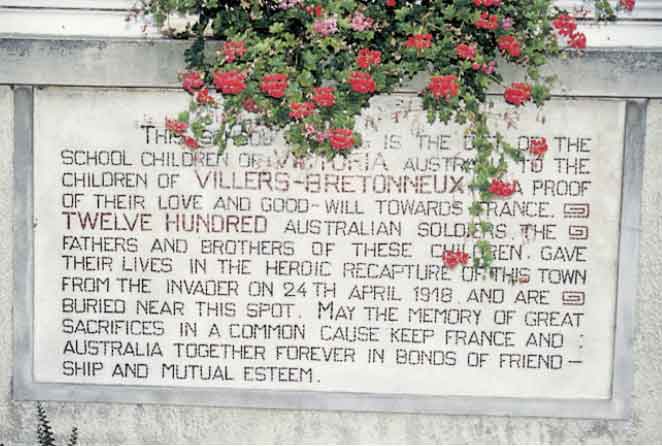

• Villers Bretonneux School & Franco-Australian Museum/15.4 miles/20 minutes/WC/Map 1/15/16/ABT1/GPS: 49.86625 2.51722

A Plaque on the school wall records that the building was ‘the gift of the children of Victoria, Australia, to the children of Villers Bretonneux as a proof of their love and good will towards France.’ 1,200 of their fathers, uncles and brothers gave their lives in the recapture of the village on 24 April 1918. Inside the school is a permanent exhibition of photographs of Australia. The Memorial obelisk in front of the school records the story of the school building project, from the visit by the President of the Australian Council on 25 April 1921, to its inauguration on 25 May 1927. The left wing of the school is marked ‘Salle Victoria’. This hall is panelled in wood, surmounted by individually illuminated carvings of Australian fauna by Australian artist J.E.F. Grant. Large photographs of Australian scenes, donated in 2003, hang above. A Plaque by the entrance records the dedication of the Museum – which is on the top floor – and which was founded by Marcel Pillon in 1975. It was then taken over by the Franco-Australian Association and completely refurbished. It was then run for them by the late M Jean-Pierre Thierry, for many years the Research Officer at the Historial, until his death in 2007 and has a centre of documentation, with a 35-seat video room showing Australian documentaries in English or French and a small book stall. The collection now includes some superb photographs, personal items, ephemera, artefacts, a model of a German A7V tank, (the type which took part in the Tank v Tank battle (qv), was later excavated near the village and transported to Wellington). Only 20 tanks of the A7V, with a crew of 18-20 people and a 57mm Maxim gun and 6 machine guns, were made in 1916. The model was made in 2004 by Franco-Aus Assoc Members Etienne Denys and Bernard Vaquez. Here too is the flag used to drape the coffin of the Australian Unknown Soldier during rehearsals for the ceremony of removing it to Australia. The family of kangaroos once housed in the Town Hall have taken up residence at the entrance here. Further improvements have been made throughout the Museum (re-opened in January 2015). Open: Nov-Feb: Mon-Sat 0930-1630; March-Oct: Mon-Sat 0930-1730. Tel: +(0)3 22 96 80 79. E-mail: neuf.fr. www.museeaustralien.com Closed: Sun and French public holidays. Annual closing: last week Dec-first week Jan. Entrance fee payable.

Return to the crossroads and turn left on rue de Melbourne. Stop at the large Ton Hall on the right in Place Charles de Gaulle.

Villers Bretonneux School memorial plaque on the wall

Bronze model of A7V Tank in the Museum

Interior of Villers Bretonneux Museum

Entrance to the Franco-Australian Museum, Villers Bretonneux

• Villers Bretonneux Town Hall/RB/15.6 miles/5 minutes/GPS: 49.86831 2.51755

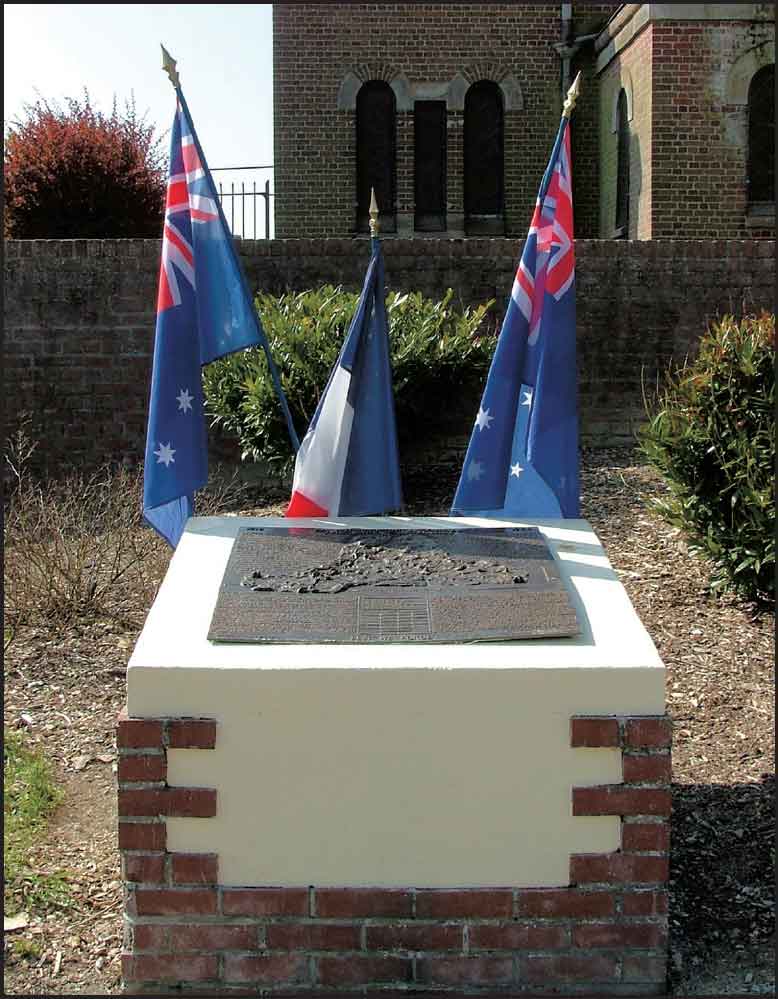

The main château in the centre of the town was also destroyed and it has been replaced by the Town Hall and memorial garden on the right. In front of it is a Ross Bastiaan bronze tablet unveiled on 30 August 1993 by the Governor General of Australia, the Hon Bill Hayden. Inside the Town Hall is a room devoted to the various connections between the village and Australia – Villers Bretonneux is twinned with Robinvale in Australia and there are still many joint activities.

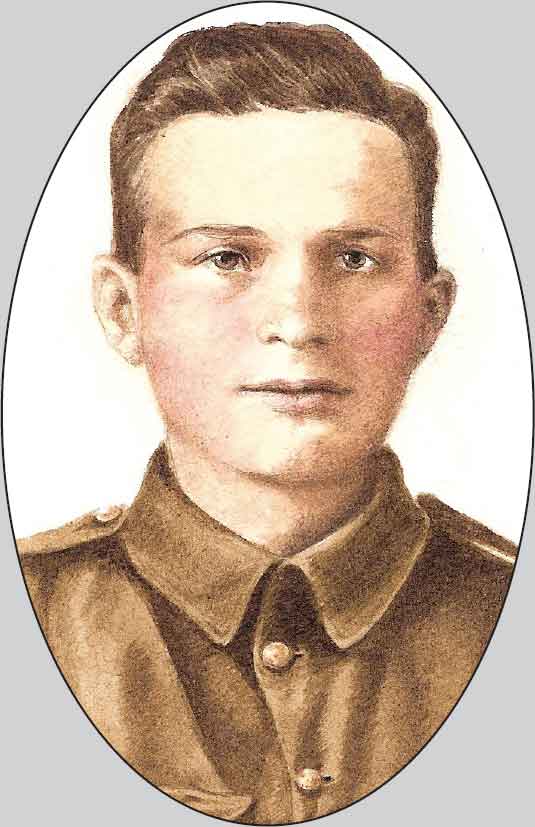

Robinvale was named after Lt Robin Cuttle from Ultima, Victoria, Australia. In 1914 Robin volunteered but was inexplicably rejected. Not to be deterred he went to England and applied to join the RFC. Again he was rejected - because of his size: he was 6ft 8ins tall. So he joined the RFA in July 1916 and served as a Lieutenant throughout the Somme battles. Whilst attached to the 9th Scots Guards at the Butte de Warlencourt in November 1916 he was awarded the MC when he assisted in capturing many German guns. In 1917 he reapplied to join the RFC and by early 1918 was flying over France with C flight of 49th Squadron as an observer. Whilst returning from a reconnaissance and bombing mission on 9 May 1918 his plane was shot down. His body was never found and in 1923 members of his family came to France to try and find where he was buried. With the help of members of his squadron and local people they found bomb pieces similar to those carried by Robin’s plane and aircraft wreckage by a crater at Caix near Villers Bretonneux. Back in Australia in October 1924 the expanding railway reached Ultima and a name was needed for the new station. Robin’s mother, Margaret, hung a sign over the station which said ‘Robin Vale’ (‘farewell Robin’ in Latin). The mother’s tribute to her dead son was eventually accepted as the name for the new township which, after initial hardships, prospered. In 1977 Alan Wood the local MP visited Villers Bretonneux and the links between the two townships were formed.

Cuttle is commemorated on the Arras Flying Services Memorial (qv).

To the left of the car park is the beautifully maintained local War Memorial with a stone Memorial to the Australians in front and a sunburst gate.

Return to the crossroads with the D1029 and turn right. Continue to the turning to the D23.

[NOTE. This is the start point for Itinerary Five, the American, Canadian and French actions of 1918. See page 289]

Drive to the parking area by the local cemetery on the right and pull in as near as possible to the small entrance at the far end.

• Villers Bretonneux Local Cemetery Allied Graves (GPS: 49.87051 2.52085), Demarcation Stone 16.1 miles/10 minutes/Map 1/18/GPS: 49.87059 2.52598

Just inside the wall is a CWGC plot containing 6 graves from 1918, 4 of them Australian.

Walk to the marker some 300m along the road.

After the war the Touring Clubs of France and Belgium, supported by the Ypres League, erected 118 official demarcation stones (for a long time it was generally thought that there were 240 stones but detailed research by Rik Scherpenberg defined the number as 118 with a private stone added at Confrecourt later making 119) along a line agreed by Maréchal Pétain’s General Staff to be the limit of the German advance along the Western Front. ‘Here the Invader was brought to a standstill 1918’, is the inscription. Four still remain in the Somme area. The authors, knowing that the Germans had actually penetrated as far as ‘OP1’ on the far side of the village, asked the local Souvenir Français organisation why the stone had not been placed there. ‘They were there for less than 24 hours’, was the reply. Local historians now wish to move the stone to what they consider to be the correct site.

The Villers Bretonneux Demarcation Stone.

Extra Visit to the French National Cemetery at Marcelcave (Map 1/19, GPS: 49.86053 2.55919) Round trip: 3.8 miles. Approximate time: 20 minutes

Continue on the D1029(N29) to a right turn, signed to Cimetière Nationale de Marcelcave on the C203. Turn right and right again and stop at the cemetery on the left.

Marcelcave, ‘Les Buttes’, Cemetery, in the area where Jean Cocteau served, was created in 1916 after the 1 July Somme Battles. It contains 1,610 burials, many concentrated from other smaller cemeteries in 1922 and 1936. It was completely re-landscaped in 1980. Like John Masefield, Jean Cocteau, who had been exempted from military service in 1910 because of his poor health, volunteered for the Red Cross in 1914. Like Masefield, Cocteau continued his writing and other artistic activities during the war, notably writing Thomas l’Imposteur about the French Marines, from his experiences at Nieuport and Coxyde in Flanders. He moved to the Somme in June 1916 and joined Evacuation Hospital No 13 at Marcelcave on 28 June in time for the 1 July Offensive. It was one of the most important French hospitals on the front and a great rail connection. From 28 June to 11 September 27,211 wounded passed through it, of which 4,170 were retained for further treatment, 829 of whom died – hence the formation of the cemetery. During his stay at the hospital, Cocteau wrote regularly to his mother, describing the hospital as ‘le district des plaintes’. He comments on the number of aeroplanes (‘Brouillard épais tissé par mille avions’ – thick fog, interlaced with 1,000 aeroplanes) and takes many photographs on Kodak film. On 16 July he is distressed by the death of Josselin de Rohan, ‘mort tout près de nous’ (killed very close to us) on 14 July. Rohan was the son of the Dowager Duchess of Rohan and brother of Marie Murat. On 27 July Cocteau left the Somme to travel to Italy and to continue work on such diverse projects as the ballet Parade and the revue Le Mot. At Christmas time that year he recalled the horrors he had seen and described, in his poem No l 1916, a ‘war crèche’ where the baby Jesus is all alone because the Three Kings were fighting, Mary was working at a hospital, Joseph guarded a road, the ox had been eaten, the donkey carried a machine gun, the Star was a signal and all the shepherds were dead and buried.

At the high tide of the German offensive of 1918 Marcelcave ended up some 300 yards behind German lines.

Return to the marker stone and pick up the main itinerary.

French National Cemetery, Marcelcave

Return to the crossroads and turn right on the D23 signed to the Australian Memorial which was widened in 2014 to take the increasing volume of traffic on ANZAC Day. Stop by the Memorial.

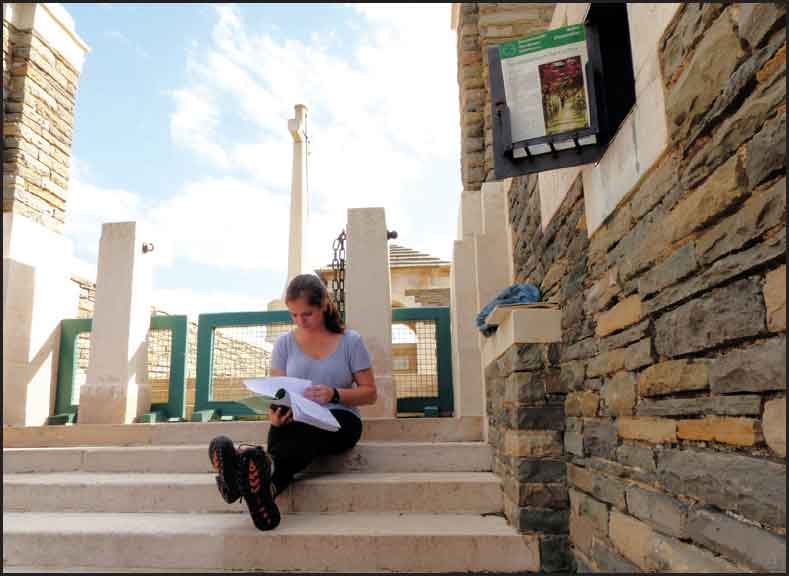

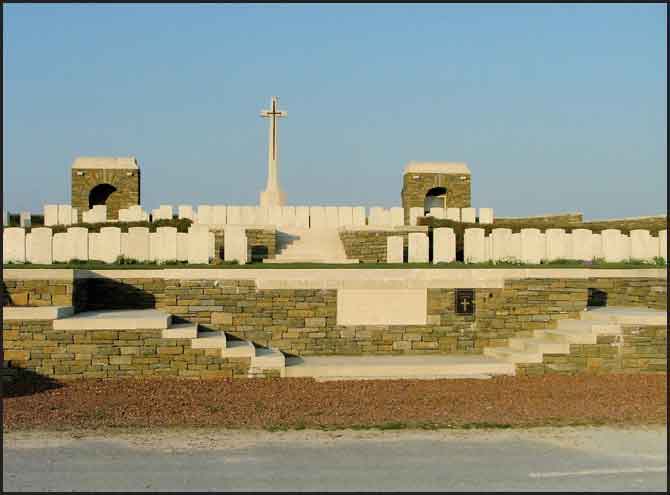

• Australian National Memorial, Interpretative Centre & Fouilloy CWGC Military Cemetery Villers Bretonneux/RB/17.3 miles/35 minutes/Map 1/11/12/OP/ABT4/GPS: 49.88613 2.50819

NOTE. In April 2007 the Australian Government (qv) announced that they were providing $2.8 million to commence plans for a major Interpretative Centre near the Memorial. Further funding will become available as the project progresses. This was reinforced in 2014 by Prime Minister Tony Abbott who confirmed that the Centre, built behind the Memorial and named after Gen Sir John Monash, would open on Anzac Day 2018. Designed by Cox Architecture, it will provide a leading-edge integrated multimedia experience and tell the story of the extraordinary efforts of the 290,000 Australians who served on the Western Front with distinction. It will offer an evocative and educational experience for visitors of all nationalities and will honour Australian service and sacrifice in France and Belgium during the First World War.

Outside the Cemetery are CGS/H Signboards. When the beautiful old avenue of hornbeam trees that led up to the Memorial was thought to have outgrown its position it was replaced with ‘France Fontaine’, a denser and more compact variety of hornbeam. It was an extraordinary coincidence that the two Australian brigades which encircled Villers Bretonneux should meet in the early hours of 25 April 1918 because three years earlier on that morning, then a Sunday, the Australian Imperial Forces had landed at Gallipoli. What happened on that terrible day lives on in the nation’s memory, and every year young Australians make their way down to the Gallipoli Peninsula to commemorate what came to be known as ANZAC Day (see Major and Mrs Holts Battlefield Guide to Gallipoli). This site, of such emotional importance to Australia, is fast rivalling Gallipoli as the destination of choice to celebrate ANZAC Day by travelling Australians, many of them young back-packers and some 6,000 visitors are expected for 2018 (and until the end of the 1980s Australian veterans regularly visited the village at this time).

Australian National Memorial & Fouilloy CWGC Cemetery, Villers Bretonneux.

Here is the Australian National Memorial which commemorates 10,797 Australians who gave their lives on the Somme and other sectors of the Western Front and have no known grave. The Cemetery, known as Fouilloy Cemetery, has 1,085 UK, 770 Australian, 263 Canadian, 4 South Africans and 2 New Zealand burials. There are some memorable private inscriptions on the Australian graves, which merit careful reading, e.g. Pte C.J. Bruton, 34th AIF, age 22, 31 March 1918 [II.C.5/7], ‘He died an Australian hero, the greatest death of all’; Pte A.L. Flower, 5th AIF, 29 July 1918 [III.B.6.], ‘Also Trooper J.H. Flower, wounded at Gallipoli, buried at sea 05.5.1915’. In VI.AB.20 lies Jean Brillant, VC, MC, 22nd Bn French-Canadian, age 22, 10 August 1918. His headstone, engraved in French, records that he volunteered in Quebec and ‘Fell gloriously on the soil of his ancestors. Good blood never lies.’ His wonderful citation is in the Cemetery Report. There is a hospital named after Brillant in Quebec. Within the lefthand hedge at the edge of the lawn before the main Memorial, there is a Ross Bastiaan bronze Plaque, unveiled on 30 August 1993 by the Governor General of Australia. From this point the heights on the left can be seen, with the tall chimney of the Colette brickworks near which the Red Baron was shot down.

Unveiled by King George VI on 22 July 1938, the impressive main Memorial, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, consists of a wall carrying the names of the missing and a 100ft-high central tower which can be climbed with due caution. If the gate to the tower is locked the key may be obtained from the Gendarmerie on the D1029 at Villers Bretonneux, though during the 100th Anniversary years this policy may change. If you intend to go up, allow an extra 20 minutes. The memorial was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and, due to delays occasioned by lack of funds, it was the last of the Dominion memorials to be inaugurated. The original plan for the Memorial had included a 90ft-high archway, but this was omitted, presumably for financial reasons. It bears the scars of World War II bullets (deliberately retained as an historical reminder) and the top of the tower was struck by lightning on 2 June 1978 and had to be extensively renovated. By facing directly away from the memorial, the cathedral and the Perret Tower in Amiens can be seen on a clear day. How near the Germans came! The war correspondent Philip Gibbs described how,

“The Germans came as near to Amiens as Villers-Bretonneux on the low hills outside. Their guns had smashed the railway station of Longueau, which to Amiens is like Clapham Junction to Waterloo. Across the road was a tangle of telephone wires, shot down from their posts. For one night nothing – or next to nothing – barred the way, and Amiens could have been entered by a few armoured cars. Only small groups of tired men, the remnants of strong battalions, were able to stand on their feet, and hardly that.”

Headstone of Jean Brillant, VC

Later he reported:

“Foch said ‘I guarantee Amiens’. French cavalry, hard pressed, had come up the northern part of our line. I saw them riding by, squadron after squadron, their horses wet with sweat. To some I shouted out ‘Vivent les Poilus’ emotionally, but they turned and gave me ugly looks. They were cursing the English, I was told afterwards, for the German break-through. ‘Ces sacrés Anglais!’ Why couldn’t they hold their lines?”

Gibbs acknowledges that:

“Amiens was saved by the counterattacks of the Australians, and especially by the brilliant surprise attack at night on Villers-Bretonneux under the generalship of Monash.”

In one of the strange coincidences of war, Gibbs was relieved to bump, quite accidentally, into his ‘kid’ brother Arthur who had become lost from his unit and was bringing up his field guns towards Amiens. ‘I had never expected to see him alive again, but there he was looking as fresh as if he had just had a holiday in Brighton.’

Continue on the D23 to Fouilloy. Turn right at the T junction with the church onto the D1 and follow signs to Péronne and ‘Toutes Directions’ towards Corbie. After some 200m there is a sign to the D71 to the right.

Extra Visit to the Private Memorial to Capt Mond & Lt Martyn (Map Side 1/20a, GPS: 49.91158 2.57892), Australian Memorial Park (Map 1/24a, GPS: 49.89977 2.58161), Memorials at Le Hamel/RB (Map 1/24b, GPS: 49.90005 2.56875). Round trip: 11.00 miles. Approximate time: I hour 15 minutes

Turn right, signed Hamelet on the D71 and continue to the centre of the village.

This is ABT5. Some 60 new British Mark V tanks and 4 re-supply tanks of the 5th Tank Brigade assembled here on 3 July 1918 and at 1030 moved south-east to their start points for the battle of le Hamel due to begin at 0310 the following morning, the attack to a first approximation being in your direction of travel. As an entirely Australian idea proposed by Monash, and executed solely under Australian auspices, the success of the operation was a major boost to Australian self-belief. Having trained the infantry and tanks together and making maximum use of artillery and aircraft, the Australians saw Monash’s plan as a blueprint for all future allied success. The action was over in under 100 minutes. Hamel was taken and 2,000 Germans were killed or captured while Australian casualties were some 1,400.

Continue towards Vaire.

In Vaire Communal Cemetery (GPS: 49.91320 2.54291) are four Australian soldiers of 8 August 1918 buried together.

Note that the ‘Red Baron Chimney’ may now be seen at 11 o’ clock on the horizon to the left.

Continue to Vaire and turn right towards le Hamel on the D71.

It was to the right of this road at Pear Trench that Private Harry Dalziel, a Lewis Gunner of the 15th AIF, won the VC, capturing a German machine gun and killing two. He was twice wounded in the action but survived until 1965.

Continue through le Hamel to the T junction by the local War Memorial and turn left. Follow the road to the left signed to Bouzencourt on the C7. Continue to the memorial on the left (4.9 miles).

The Memorial is just before the village and surrounded by a small, well-tended garden. The French inscription translates, “To the memory of Capt Francis Mond, RFA and RAF, age and Lt Edgar Martyn RAF of 57th Squadron who fell gloriously in this area battling against three German aeroplanes on 15 May 1918. Per ardua ad astra.” They were flying their DH4 after attacking ammunition dumps at Bapaume and were brought down at 1250 by Lt Johannes Janzen of Jasta 6, whose Fokker DR.I had been shot down on 9 May by 209 Squadron but survived. Janzen scored 13 victories before he was brought down again during a dogfight on 9 June 1918 with a SPAD during which he shot off his own propeller. He lived until the 1980s.

The dogfight which brought down Mond and Martyn was witnessed by 31st Aust Bn and one of their officers, Lt A.H. Hill, MC, went out under fire, extricated and identified their bodies. He then had them sent down to Bn HQ by river and their personal effects were sent on to Mond’s family. Strangely, the bodies which had been escorted down the river, then seemed to disappear. An extensive search was undertaken by the Australians, by 57 Squadron and the CWGC prompted by Mond’s Mother, who wrote to every officer and NCO who might have any information, and visited over thirty cemeteries, keeping in touch throughout with Martyn’s wife. Her efforts bore fruit in 1922 when she became convinced that two named graves in Doullens Communal Cemetery Extension No. 2 (qv) actually contained the bodies of her son and of Martyn. One grave was exhumed, watched by Mrs Mond and the father of the man named therein, Capt J.V. Aspinall. The body was indeed found to contain Mond so the adjoining grave was opened and contained Martyn, not the named Lt P.V. de la Cour, whose grave turned out to be the next one. Capt Aspinall is now commemorated on the Arras Memorial.

Memorial to Capt Mond & Lt Martin RAF, Bouzencourt

In 1919 Mond’s father Emile had bought the land here where his son’s plane had crashed and erected the monument you see today and surrounded it with chains supported by stone pillars, within which enclosure he planted trees, shrubs and flowers. The family continued to visit regularly, the last recorded visit being by Mond’s sister in 1951. As the family then became untraceable the Commune of Hamel adopted it and they maintain it still. During WW2 the Cross of Lorraine and letter V were scratched on the stone, probably by the Resistance.

Edgar Martyn was a Canadian and came to Europe with the 19th Bn Can Inf before being commissioned into the RFC as a Lt Observer on 12 February 1918.

On the heights beyond the Memorial can be seen the tall chimney of the brickworks in the area where the Baron von Richthofen came down.

Continue to the bottom of the road to turn and return to le Hamel. On entering the village turn left uphill following the sign to Monument Australien, and left again.

There is a barrier and a sign with the park’s opening hours: 0900-1800

1 April-31 Oct and 0900-1600 1 Nov-31 March. Contact the Mayor on +(0)3 22 96 88 06.

Continue to the large parking area on the right.

The Australian Corps Memorial Park, ABT16/OP/GPS: 49.89977 2.58161

The land for this Memorial was acquired by the Australians on the 80th anniversary of the Battle of le Hamel. Following its 2008 renovation and redesign it is now a dignified, informative and pleasantly landscaped area.

Stand in the open shelter and look over the Valley of the Somme. At 1 o’ clock is the CWGC Cemetery Dive Copse (qv). At 12 o’clock on the skyline is the Australian 3rd Division Memorial (the 3rd and 4th Divisions defended this area during the battle of Amiens in 1918), at 10 o’ clock is the chimney of the Richthofen crash site brickworks, at 9 o’ clock are the twin towers of Corbie church, from which broad direction the Australian attack came.

On 4 July 1918 this was a German position known as the Wolfsberg and was on the final objective line for the assault. Apart from being a great success, a novel aspect of the attack was that the Australians were re-supplied by parachute. The choice of 4 July for the attack had been influenced by the hoped for participation of the recently arrived American 131st and 132nd Regiments, but Pershing ruled this out, though four companies did take part incurring 100 casualties. It was from these positions that the Australians set out on 8 August in the Allied offensive that marked the beginning of the end for the Kaiser, a day that Ludendorff called Der Schwarze Tag (The Black Day).

A path then leads towards the main Memorial and recreated trenches, from which the Australian Memorial at Villers Bretonneux may be seen to the right. Along it are Information Panels with maps, photos and individual stories about the campaign and the VCs and MoHs of:

1. Pte Henry (Harry) Dalziel (qv). Driver Dalziel’s VC was gazetted on 17 August 1918 and was for his action as a Lewis gunner, who after silencing the enemy guns in one direction, dashed at gun fire from another direction. There, using his revolver, he killed or captured the entire crew and gun, despite being severely wounded in the hand, finally capturing the final objective. He was wounded again, in the head, and had inspired his comrades and saved many lives. The action took place at Pear Trench (qv).

2. Lance Cpl Thomas (Jack) Axford, MM, 22 years old, was awarded his VC (gazetted on 17 August 1918) for his action in clearing Vaire and Hamel Woods of German defenders. Single-handedly he entered a German trench and took the machine gunners in it, killing 10 and taking 6 prisoners.

3. Cpl Thomas Pope, who served with Coy E of 131st Inf, 33rd US Inf div, the first soldier to be awarded the Medal of Honour in WW1. It was for his action at le Hamel on 4 July 1918 when going alone he rushed a machine gun nest, killed several of the crew by bayonet and held off others until reinforcements arrived and captured them.

The Memorial. The shiny black tiles on the original 1998 Memorial started to drop off shortly after it was inaugurated and in 2006 it was in such a bad state of repair that plans were made to demolish and rebuild it. In March 2007 the Australian Government announced that they were allocating $7.9 million towards a ‘facelift’ for the Memorial. It was re-inaugurated on 8 November 2008. The new Memorial, maintained by the CWGC, is constructed as three blocks of curved granite set in a semi-circle with the Australian Forces sunburst badge in the centre block. It bears a quotation from the speech of French PM Georges Clemenceau of 7 July 1918, “… I have seen the Australians, I have looked in their faces. I know that these men will fight alongside us again until the cause for which we are all fighting is safe for us and our children.”

Further repairs were required in 2014/5.

Australian National Memorial, le Hamel

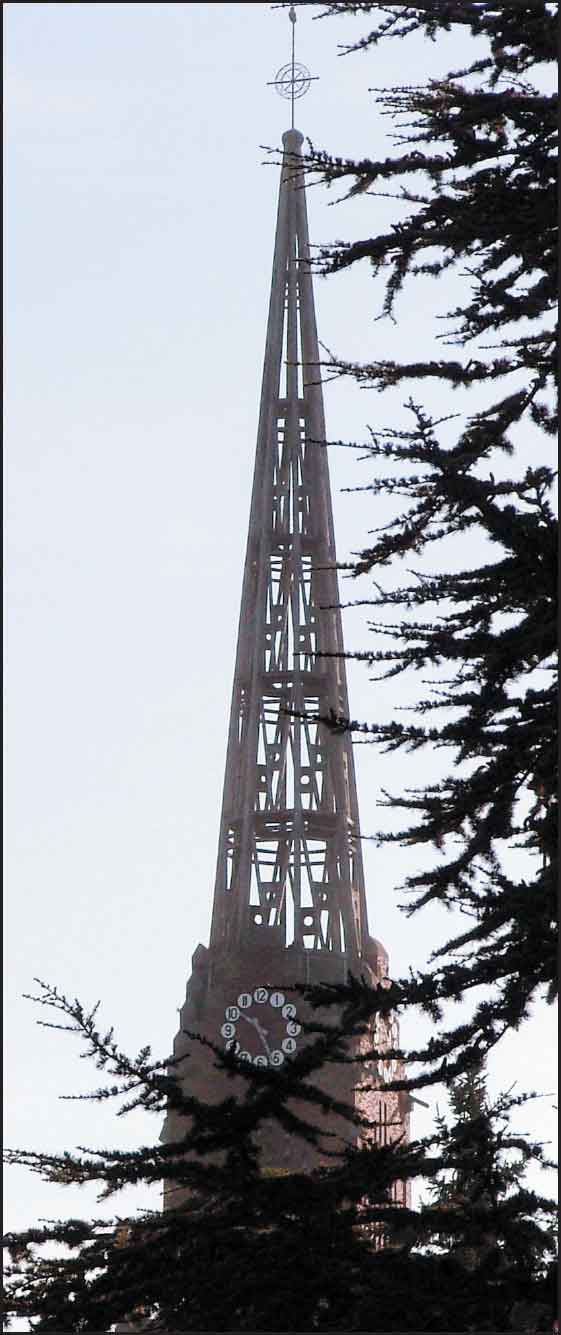

Beyond the Memorial is a section of original trenches. On the horizon beyond them the distinctive spire of La Motte Church, on the N29 some 2 miles away, may be seen.

Early in August the Australian 1st Division moved down to the Somme from Ypres and continued the chase to the east. Commanding the 3rd Brigade was Brigadier Gordon Bennett, the youngest Brigadier in the Australian Army, who would later be immersed in controversy over his conduct following the fall of Singapore in WW2.

Return towards le Hamel.

On descending towards the village the top of the Australian National Memorial at Villers Bretonneux may be seen straight ahead.

Turn left and then right and stop by the church on the left.

Remnants of Australian trenchlines, behind the Memorial.

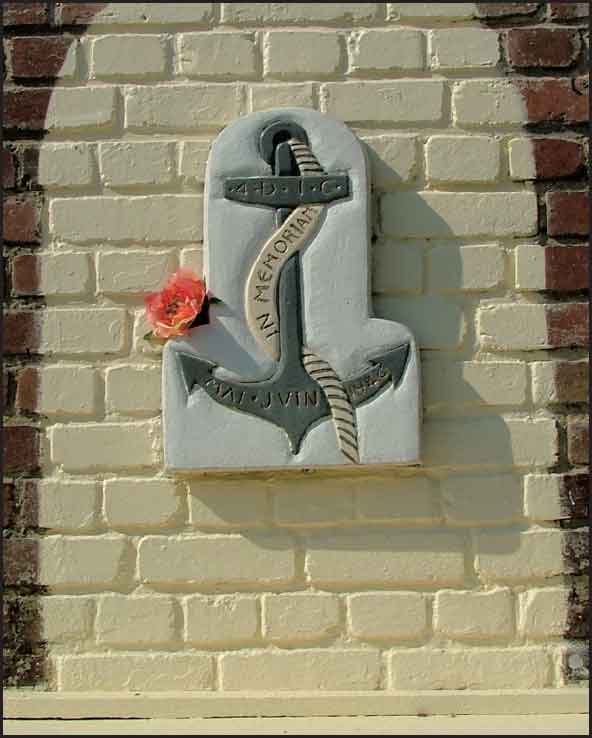

In front of the church is a Ross Bastiaan commemorative Bronze Plaque (GPS: 49.90005 2.56875) about the Battle of le Hamel, sponsored by Hugh and Marcus Bastiaan, John and Hazelle Laffin and Carbone-Lorraine Aust. On a wall to the right of the Church is a May/June 1945 Plaque with an anchor to the Senegalese of the 4th Col Inf Div (c.f. similar Plaque in Itinerary 5 at Mailly Raineval) who had a medical facility nearby. This is rue du General Monash.

Return to the D23, turn right and rejoin Itinerary Three.

Ross Bastiaan Plaque, le Hamel

Plaque to 4th Col Inf Div, le Hamel

Continue into Corbie, crossing the River Somme en route and follow signs to Centre Ville passing the picturesque, fairy castle-like Hôtel de Ville and war memorial on the left.

Corbie. The Château was built in 1863 and bought by the town in 1923. The Hotel de Ville and surrounds have recently been restored and landscaped into a pleasant park.

After 100m park in the Place de la République (GPS: 49.90854 22.51219).

Note. On Friday there is a market in the square (now also beautifully landscaped) so it will not be possible to park here. To the left is the splendid ‘Porte d’Honneur’ to the Abbey. The key to the church is held in the Tourist Office on the corner. Its opening hours vary according to the season, but it is usually closed on Sundays - other than in July and August - and often on Monday mornings. It shuts for lunch from 1200-1430. Over the road is the excellent restaurant La Table d’Agathe with superb regional dishes. Closed Sunday night and Monday and the first two weeks in July. Tel: + (0)3 22 96 96 27.

Walk along rue Charles de Gaulle to the church.

Just before it is the restaurant Le Fauquet’s (closed Sun and Mon evening). Tel: +(0)3 22 48 41 17. Good choice of menus, fast service if required.

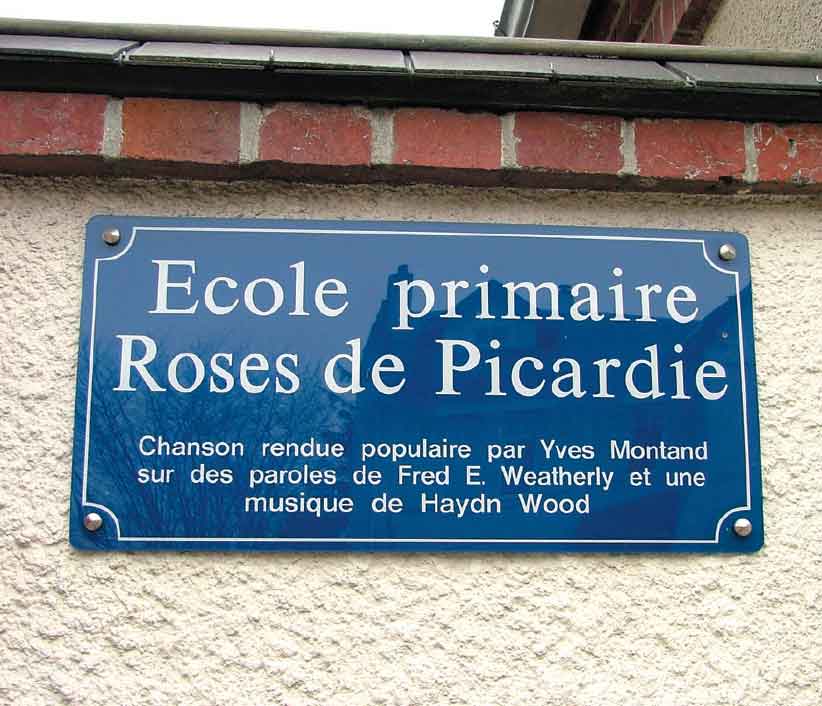

Continue towards the Church, passing the school. This is called ‘Rose de Picardie’. Continue to the Church.

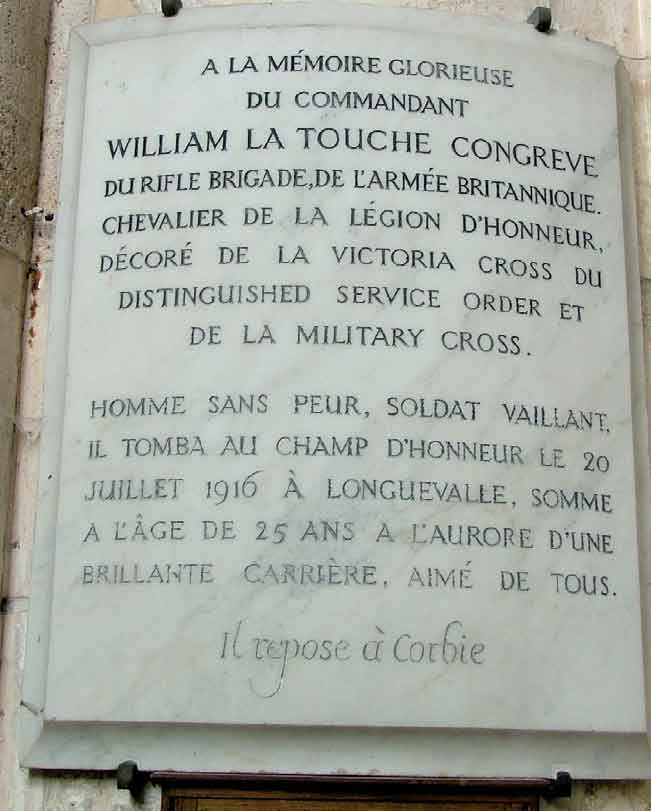

• Congreve Plaque, Corbie Church/19.7 miles/10 minutes/Map 1/10/GPS: 49.90878 2.51026

Corbie has a fascinating history. It was attacked by the Normans in 896AD, in 1415 Henry V, desperately seeking a Somme crossing, was attacked here by a small force of French Knights, in 1475 the town was taken and burnt by Louis X1, in 1636 it was taken by the Spanish who were chased out by Louis XIII and Richelieu, and it was badly damaged in the French Revolution. In the distinctive twelfth-century church of Saint-Etiennes, whose architecture shows the transition between Roman and Gothic styles, is a Plaque, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, to ‘Billy’ Congreve VC (qv).

Return to the Place de la République.

Across the square at No 8 is the delightful ‘Maison d’Hôte’ Le Macassar (see also Tourist Information below). Five sumptuous rooms/suites furnished in period (from ‘Colonial’ through ‘Art Nouveau’ and ‘Art Deco’) style but with state of the art plumbing in a superb private residence which was extensively renovated in the 1920s and ‘30s. Hosts Miguel and Ian encourage guests (but no young children please – some of the antiques are too precious) to makes themselves at home in the glorious public rooms and courtyard. Tel: +(0) 3 22 48 40 04. E-mail: bookings@lemacassar.com Website: www.lemacassar.com

From the Square take the D1 signed to Péronne, continue past the Hospice de Corbie on the left. Turn right following the green CWGC sign. Park at the cemetery.

• Corbie Communal Cemetery & Extension/20.4 miles/10 minutes/ Map 1/20/GPS: 49.91528 2.52037

Just at the top of the steps leading to the cemetery, a headstone is inscribed, ‘Major W. La Touche Congreve, VC, DSO, MC, Rifle Brigade. 20 July 1916. Légion d’Honneur. In remembance of my beloved husband and in glorious expectation.’

Congreve, affectionately known as ‘Billy’, was the VC winner son of a VC winner father, Lt Gen Sir Walter Congreve VC, CB, MVO (who was commanding XIII Corps on the Somme at the time of his son’s death). A conspicuously brave, and immensely popular officer, Billy Congreve kept a forthright diary until 17 January 1916, (which has been edited by Terry Norman as Armageddon Road). He was killed on 20 July 1916 at Longueval by a sniper (qv). He had been married on 1 June 1916 to Pamela Maude. Her poignant message on her husband’s headstone refers to the fact that she was pregnant. She christened their daughter Gloria. A fellow officer had described Billy as ‘absolutely glorious’.

Roses de Picardie School, Corbie.

Memorial Plaque to Maj William La Touche Congreve, in Corbie Church

Corbie Comm Cem with headstone of ‘Billy’ Congreve, VC, DSO, MC

On the headstone of Lt F.C. Sangster of the R Warwicks the personal message is on a bronze Plaque. Through the archway is the grave of CWGC worker, George Hill, 1946.

Return to the Hospice junction, turn right and continue to the female statue at the Y junction.

• Colette Statue/20. 8 miles/GPS: 49.91668 2.51662

The statue, known as ‘Colette’ (after the young citizen of Corbie who founded the Clarisse Religious Order), was unveiled in the presence of the Bishop of Amiens and the Curé of Corbie to commemorate citizens of the town who were killed in World War I. Colette managed to found seventeen monasteries in her life-time, during the difficult times of the Hundred Years’ War.

Statue of Colette, Corbie

Extra Visit to Heilly Station CWGC Cemetery & Private Memorial to L Cpl O’Neill/Map 1/22/23/GPS: 49.94080 2.54203

Round trip: 4.8 miles. Approximate time: 25 minutes

Take the left fork on the D23 and after approximately 0.8 miles, fork right on the D120 signed Méricourt l’Abbé. After 1.5 miles (driving parallel to the R Somme and railway to the left) turn right following green CWGC signs at a crossroads. (Heilly ‘Station’ is signed to the left).

The railway ran through here from Amiens to the front and Heilly was the site of one of the Casualty Clearing Stations to which ambulance trains were due to run after the battle of 1 July 1916. As you turn right, the station house can be seen on the C11 to the left. This is a particularly lovely cemetery – in a quiet, rural setting, with beautiful flowers and shrubs – and unusual, partly due to the vastly greater number of casualties that arrived at the CCS than were anticipated. Men had to be buried two or three to a grave – a rare occurrence in a British cemetery. There was not, therefore, room to engrave the men’s regimental badges, and so many of them are incorporated into the colonnaded brick wall on the right as you enter. There is also a Private Memorial erected by his comrades to L Cpl J. P. O’Neill of 13th NSW battalion, AIF, who was killed on 6 January 1917 when a grenade accidentally exploded. He had been recommended for a Military Medal.

It was to this CCS that Henry Williamson’s fictional hero Phillip Maddison was brought and there is a totally realistic description of Maddison’s wounding after going over the top at Ovillers, his crawling painfully back to find basic treatment at the First Aid Post, then being wheeled on a stretcher to the Advanced Dressing Station at Albert, being encouraged by an RC Padre, given an injection and then lifted into a Ford ambulance and driven to Heilly. There he ‘was carried into a hut for officers’, laid on a rubber sheet and covered with a blanket, fed tea, bread and butter and jam and given ‘the latest number of The Bystander’. This was the magazine which carried the popular cartoons of Bruce Bairnsfather, known as Fragments from France and which featured ‘Old Bill’ (see page 93).

Return to the Colette statue and continue with the main itinerary.

Heilly Station CWGC Cemetery, showing Private Memorial to L/Cpl O’Neill

Keep to the right on the D1 signed to Péronne and Bray, passing on the right a picnic site (Pointe de Vue de Sainte Colette) with tables and benches and a superb view over the River Somme. Continue to the brickworks on the left with a tall chimney.

• Von Richthofen Crash Site, Vaux-sur-Somme/22.5 miles/5 minutes/Map 1/21/GPS: 49.93248 2.54136

The chimney, now crumbling somewhat at the top, is visible for miles around and makes a good reference point. The precise cause and location of the Baron’s crash is still open to some debate, but many qualified experts place it in the vicinity of the brickworks.

The ‘Red Baron’, Baron Manfred von Richthofen, was credited with eighty kills. His squadron, Jasta II, was known as the ‘Flying Circus’ because of the bright colours of their planes. Richthofen’s own Fokker triplane DR-1 425/17 was vermillion. They were based at Cappy, just south of the River Somme and south east of Bray. On Sunday 21 April 1918 the squadron went up at mid-morning, after Richthofen had posed for a photograph for a mechanic, despite the superstition held by many pilots that being photographed just before a mission meant that one would not return. The Baron did not. After an active dog fight with British RE 8s and Camels led by Capt A. Roy Brown, a Canadian with eleven kills, von Richthofen crashed near this spot, coming down from your right. Brown claimed the victory. So did Australian Lewis gunners of 14th Artillery Brigade near Vaux. Subsequent research gives credence to the Australian claim. Even the angle at which the fatal bullet entered the Baron’s chest – from below, not above (as Brown was flying) – points to a hit from the ground. What is indisputable is that Richthofen’s apparel and possessions and his red tri-plane were soon stripped, as by a plague of locusts, by souvenir hunters. Many items found their way to Australia and several have since been donated to the Australian War Memorial. Von Richthofen was buried in Bertangles (Map 1/5, Western Approach) on 22 April, with ceremony, by the Australians. In 1925 his remains were re-interred in Fricourt German Cemetery (Map J34) and from there were transferred to his family home in Schweidnitz, in eastern Germany. Contemporary accounts claim that only the skull had been removed and P. J. Carisella, American author of a book on the Baron’s death, states that he unearthed the rest of the skeleton in Bertangles in 1969 and that he presented it to the German Military Air Attaché in Paris.

The brickworks near where Manfred von Richthofen (the ‘Red Baron’) was shot down

In the Kent Battle of Britain Museum, Hawkinge, www.kbobm.org there is an excellent von Richtofen display, including a replica of his triplane (made for the film Flying Boys) and a realistic maquette showing the area of the brickworks.

Continue. Park by the memorial on the left.

• Australian 3rd Division Memorial/24.3 miles/5 minutes/Map 1/23a/GPS: 49.93605 2.57959

The obelisk is similar to the 1st Division Memorial at Pozières (Itinerary One). It lists the battle honours of the Division, including The Windmill (Pozières), Bray and Proyart (both the latter are seen on this Itinerary). It stands pretty well on the final line the Germans reached by August 1918 which ran roughly north to south across the road here. The Division, raised in Australia, was formed on Salisbury Plain in July 1916 and reached Flanders under General Monash in December that year and the Somme in March 1918. The Memorial overlooks the ground across the other side of the Somme where four Australian Divisions (2, 3, 4 and 5) attacked roughly parallel to your direction of travel in the early morning fog of 8 August 1918. This side of the Somme were the British 18th and 58th Divisions. It was a remarkable assault, with fine co-operation between infantry, cavalry, tanks and aircraft. Determined efforts had been made to keep preparations for the attack secret and it was launched without a preliminary bombardment.

The British front (the Fourth Army – III Corps under Butler where you are now, to the south, the Australian Corps under Monash and then the Canadian Corps under Currie) stretched about 23km south from around Albert which is over to your north front. The unsuspecting German Second Army of six weak divisions, without a single tank, were suddenly confronted by 360 heavy tanks, 96 Whippet light tanks, 1,900 aeroplanes (against 365) and accompanying bombardment from 2,650 guns and a total force of 16 divisions. In his book, Wings of War, Rudolf Stark, serving with Jagdstaffel 35, tells how he flew over the front of 8 August, and how the sky was full of aircraft:

“There are fights in the upper air. There are fights in the lower air. The numerical superiority of the enemy gives him the advantage, so it does not matter where we fight …. But the ground swarms with men in brown. They crouch in every shell hole and run forward along every hollow. Grey squat things roll through their midst – tanks. Here, there, everywhere.”

Except at the extremities, an advance of more than 8km was achieved everywhere. Although the Germans recovered quickly, and the attack lost its momentum after the first day, for Ludendorff, the German Commander, it was the final straw that broke the back of his determination to win.

In Germany more than 1.5 million workers were on strike, the spreading influenza epidemic was weakening his armies, the civilian population was starving and Ludendorff was suffering from nervous exhaustion. Although the gains by the Allies on 8 August did not compare to the territorial conquests of the Germans in their March Offensive, the ‘Kaiserschlacht’, the shock of 8 August loosened the Germans’ grasp upon the initiative and it passed to Foch.

Around the Memorial are Information Panels, detailing the Division’s casualties on the Western Front – 6,200 killed, 24,000 wounded, etc. By looking across the Somme River towards the high ground the Australian Memorial at le Hamel can be seen and the church on the horizon straight ahead is La Motte Warfusée to the right of the windmills.

Continue on the D1, passing on the right a sign to CWGC Dive Copse Cemetery (Map 1/23b, GPS: 49.92902 2.60492).

This was begun during the 1916 battles and is the cemetery that can be seen from the Australian Memorial at Le Hamel.

Continue to the next cemetery on the right.

Memorial to Australian 3rd Division, Sailly le Sec

• Beacon CWGC Cemetery/26.0 miles/5 minutes/Map 1/23c/GPS: 49.93700 2.61650

The Cemetery report here records that the

“… first fighting in this part of the Somme took place on 26/27 March 1918 when the Third Army withdrew to a line between Albert and Sailly-le-Sec. This line was held until 4 August when it was advanced nearly to Sailly-Laurette and on 8 August, the first day of ‘The Battle of Amiens’, Sailly-Laurette and the road to Morlancourt were disengaged.”

Burials began here as the Third Army withdrew before the German onslaught of March 1918. Others were made by the 18th Div Burial Officer on 15 August. The cemetery was then greatly increased after the Armistice by the concentration of 600 graves from the battlefields and small cemeteries around. There are many almost unbearably poignant personal messages on the headstones here and some proud parental statements in the Cemetery Report of sons’ academic and career achievements. The Cemetery was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and named after a brick beacon on the ridge. There are some 570 UK burials and 190 Australian. At 9 o’clock the Golden Madonna at Albert may be seen and to her right on the high ground the Thiepval Memorial.

Continue over the crossroads with the D42 and turn right at the next crossroads onto the C2, signed to Chipilly and Cerisy. We probably need to point out here that road numbers on the ground do not always match the numbers given on maps!

This road runs down towards the Somme at Chipilly where a spur (roughly a direct extension of this road) juts south into a bend of the river. On 8 August 1918 the Allied assault south of the Somme made advances of 8km or more in the day, but at Chipilly village and on the spur the Germans made a stand. 58th (London) Division supported by 131st Infantry Regiment of the 33rd (American) Division made a joint assault here at 1730 hours on 9 August. The Americans lined up parallel to, and 50m to the right of, this road, having had to march in double-time for 7km to reach the start-line. In the following action, supported by the 4th (Australian) Division attacking the village from south of the river, both Chipilly and the spur were captured – the latter, it is said, by a six-man Australian patrol. Corporal Jake Allex of 33rd Division won the Congressional Medal of Honour for single-handedly destroying a German machine-gun post, killing five of the enemy and taking fifteen prisoners. Allex survived the war and died in 1959. In 2006 a short documentary film called ‘Corporal Jake’ was made about his action.

Continue downhill on the C306 to the church road junction in Chipilly.

Beacon CWGC Cemetery

• 58th (London) Division Memorial/29.0 miles/5 minutes/Map 1/26/GPS: 49.90889 2.64946

There is a CRP Signboard beside the Memorial. This striking Memorial, sculpted by Henri-Désiré Gauque, 1858-1927, a well-known French sculptor who excelled at animal figures, is of a soldier saying goodbye to his dying horse and is reminiscent of the famous Mantania painting Farewell Old Man. Unusually it commemorates not only 58th Division, but also the French, Canadian and Australian action of 8 August. The Americans were not mentioned, presumably because on 8 August they were in reserve. When the Australians came to enter the village from the south they found that the Germans had blown both bridges across the river. With typical Aussie ingenuity they took the girders from the longer bridge and balanced them on the piers of the shorter to restore the crossing.

Memorial to 58th London Division, Chipilly

[N.B.] Cérisy-Gailly Mil CWGC Cemetery (GPS: 49.90424 2.63174). By turning right downhill at the crossroads and continuing over the bridge towards Cérisy, (with picturesque views to each side over the Somme and its tranquil pools - paradise for fishermen) this Cemetery may be reached. Continue through Cérisy village, following signs to Cérisy-Gailly French National Cemetery, with a British Communal Plot attached and to Cérisy-Gailly Mil Cem. This is beyond the Brit Com Plot and to the left.

In it (in D13) is buried Squadron Commander John (‘Jack’) Petre, RFC, 13 April 1918. Before his accidental death (for details see Elsie & Mairi Go to War by Diane Atkinson) this distinguished pilot was due to marry Mairi Chisholm, one of the famous “Two at Pervyse”.

Entrance to Cérisy-Gailly CWGC Cemetery

Turn left past the church and continue uphill on the C7, signed to Etinehem and almost immediately there is the local cemetery on the right with good parking.

• Chipilly Communal Cemetery & Extension/29.1 miles/5 minutes/Map 1/28a/GPS: 49.91066 2.64999

In the Cemetery are a number of British and French military graves from July 1916. The plot was started in August 1915 and used until March 1916. It contains fifty-five UK burials (including Rifleman E. F. Slade, QVR, who was drowned whilst swimming in the Somme, 12 August 1915) and four French. The Extension was used between March 1916 and February 1917 and contains 31 graves. The Cemetery has extensive views over the Somme Valley from the back wall.

Continue.